In their natural habitat, plants are continuously challenged by adverse environmental conditions. Among them, cold stress (CS) is a major environmental factor limiting agricultural productivity and geographic distribution (Chinnusamy et al., 2007). In this respect, chilling (15-0°C) and freezing (<0°C) stress should be distinguished (Thomashow, 2010). CS responses at the cellular level are characterized by an extensive reprogramming of gene expression and metabolic fluxes (Stitt and Hurry, 2002; Miura and Furumoto, 2013). Clearly, these modifications are mainly linked to the onset of tolerance mechanisms, which ultimately lead to acclimation. Several metabolites are known to contribute to this process, including amino acids, polyamines, polyols, and soluble sugars (Krasensky and Jonak, 2012 and references therein). Among them, particular focus was recently given to understand the multifunctional role of soluble sugars in enhancing cold tolerance (Nägele and Heyer, 2013).

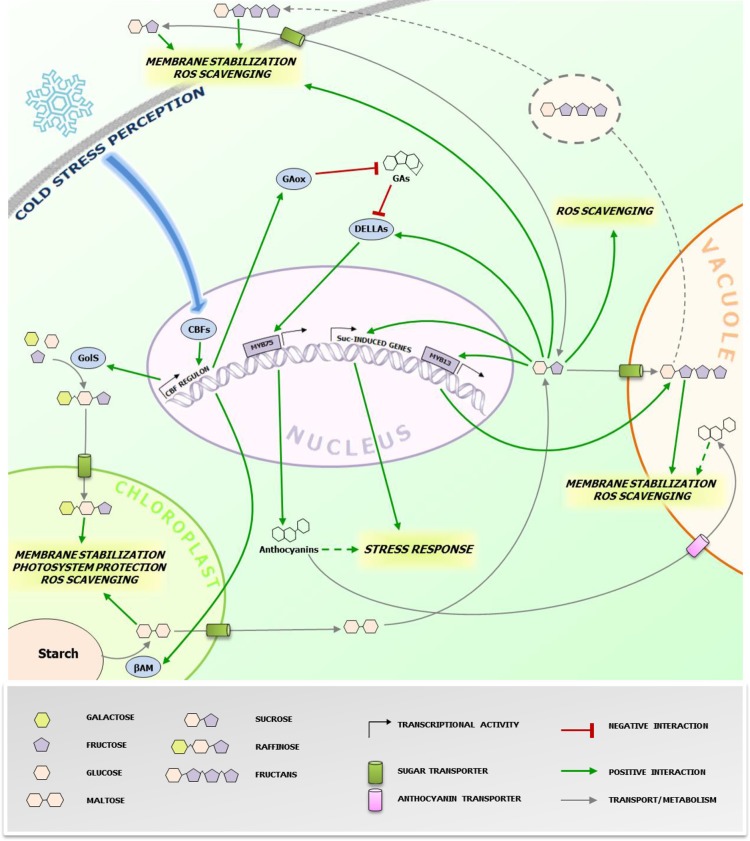

Accumulation of soluble sugars following CS is known since long (Levitt, 1958), including studies on their potential roles in stabilizing biological components, particularly for Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides (RFO) (Santarius, 1973). Despite this well-known correlation, more recent investigations shed light on the potential underlying biological mechanisms involved (Valluru et al., 2008; Sicher, 2011; Peng et al., 2014). One of the major factors affecting overall cellular stability under CS is membrane phospholipid composition regulating membrane fluidity (Ruelland and Collin, 2011 and references therein) associated with cold stimulus perception, as suggested by the protein kinases cascade activation triggered by dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-mediated membrane rigidification (Furuya et al., 2014). Different saccharides are capable to directly stabilize biological membranes under stress conditions. Sucrose (Suc) can directly protect cell membranes by interacting with the phosphate in their lipid headgroups, decreasing membrane permeability (Strauss and Hauser, 1986). Fructans, fructose-based oligo- and polysaccharides, and RFO can increase stability of phospholipidic mono- and bilayers by direct insertion between polar headgroups (Vereyken et al., 2001; Hincha et al., 2003). Fructans are localized in the vacuole, suggesting that their contribution to membrane stabilization may be restricted to the tonoplast. However, their detection in the apoplast of cold-stressed plants also suggests a role in the protection of the plasma membrane, where they can be delivered by a vesicle-mediated transport (Valluru et al., 2008). This scenario seems to be different for RFO. Despite their cytosolic biosynthesis, their protective action may be restricted to chloroplast inner membranes, as suggested by research on Arabidopsis thaliana (Nägele and Heyer, 2013 and references therein). Thus, specific changes in subcellular concentrations of potential stress protectants may greatly influence successful responses (Lunn, 2007) (Figure 1). The regulation of the activity and/or expression of soluble sugar transporters, especially those involved in chloroplast and Tonoplast Monosaccharide Transporters (TMTs) (Wormit et al., 2006) and Sugars Will Eventually Be Exported Transporters (SWEETs) (Klemens et al., 2013), may play a central role in such processes. Cold-stressed AtSWEET16 overexpression lines showed increased freezing tolerance and increased glucose (Glc) and Suc levels (Klemens et al., 2013). The fructose (Fru)-specific transporter AtSWEET17 plays a primary role in Fru homeostasis following 1-week 4°C treatment (Guo et al., 2014b). These authors suggested that the Fru-specific transport features of this carrier may be mediated by a Fru-specific signaling pathway. Taken together, these works indicate that the activity and/or expression of sugars transporters may be regulated by sugar signaling, affecting the subcellular distribution of sugars and overall cellular sugar homeostasis, which may be tightly linked to the cellular redox homeostasis (see next paragraph). In that respect, it will be particularly interesting to characterize the nature of the Raffinose importer in the chloroplast (Schneider and Keller, 2009) and to decipher its activation by sugar- and hormone signaling under CS in tolerant accessions.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of cold-induced saccharides at the subcellular level. The figure highlights the (putative) action sites of sugars accumulating during CS responses in higher plants cells. The grey dotted line refers to the proposed vesicular transport mechanism of fructans from the vacuole to the plasma membrane in fructan accumulating species (Valluru et al., 2008). The green dotted line refers to the possible roles of anthocyanins in CS protection. Anthocyanins are also imported in the vacuole through ABC class transporters (Francisco et al., 2013), where they can contribute in alleviating CS. The blue arrow represents the signaling pathway leading to the activation of CBFs. The biosynthesis and metabolic conversions of the sugars involved is oversimplified and represented by grey arrows. CBFs, C-repeat binding factors; GAs, gibberellins; GAox, GA oxidase; GolS, galactinol synthase; βAM, β-amylase; Suc, sucrose. Specific effects of different sugars/anthocyanins are highlighted in italic. Readers are referred to the figure legend and the text for further details.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production partially contributes to chilling and freezing damage (Nishizawa et al., 2008 and references therein). Recently, several carbohydrates were proposed as important components of the cellular ROS scavenging system, perhaps in synergism with other components such as phenylpropanoids (Couée et al., 2006; Nishizawa et al., 2008; Van den Ende and Valluru, 2009). Living cells do not possess an efficient enzymatic system to scavenge the highly deleterious hydroxyl radical (·OH) (Gechev et al., 2006). Furthermore, carbohydrates have generally higher scavenging ability against ·OH as compared with other radicals, such as superoxide (O·−2) (Stoyanova et al., 2011). The recent works of Peshev et al. (2013) and Peukert et al. (2014) provided new mechanistic insights into this process. They observed that Fenton reaction-derived ·OH scavenging by fructans in vitro lead to the formation of new oligosaccharides and oxidized sugars. Such oxidized sugars can also be found in vivo, suggesting that fructans function as scavengers in planta (Peukert et al., 2014). Alternatively or additionally, fructans have been proposed as stress signals, further amplifying stress responses that may be initiated by Suc-specific signaling pathways (Van den Ende, 2013).

Contrary to fructans, the signaling capacity of small metabolic sugars is widely recognized (Ramon et al., 2008; Ruan, 2014) and several lines of evidence indicates their involvement in regulating various stress responses (Van den Ende and El-Esawe, 2014). Recently, a possible mechanistic link between sugars and CS tolerance was proposed by Peng et al. (2014). They successfully expressed PtrBAM1, a stress-responsive chloroplastic β-amylase-coding gene from Poncirus trifoliata in tobacco, under the constitutive promoter CaMV35S. They found that β-amylase activity was strongly enhanced by CS accompanied with a massive accumulation of maltose and other soluble sugars (Figure 1). Importantly, this breakthrough paper provides the first evidence that PtrCBF1 (C-repeat-binding factor 1), a transcription factor belonging to a family of central regulators of CS responses highly conserved throughout plants kingdom (Chinnusamy et al., 2007), can bind directly to the promoter of PtrBAM1, providing a unique link between CBF-mediated cold responses and sugar dynamics. Thus, cold-dependent sugar accumulation may, at least partially, depend on the CBF transcriptional cascade, as previously suggested by the CBF-dependent metabolic changes observed during CS (Cook et al., 2004).

It is noteworthy that Suc can trigger fructan synthesis and accumulation in fructan accumulators such as wheat, by activating the transcriptional factor TaMYB13, which directly controls gene expression of enzymes involved in fructan synthesis (Kooiker et al., 2013). A possible scenario for future research could be that CBF-dependent increases of Suc under CS may trigger fructan synthesis and accumulation in wheat and other fructan accumulators, allowing a highly coordinated metabolic countermeasure onset, via an orchestration of direct and indirect signaling and scavenging mechanisms, as proposed above (Figure 1). Accordingly, in winter wheat, fructans accumulate in young plants during cold acclimation in the autumn, and this process is also associated with increased snow-mold resistance (Yoshida et al., 1998). The high correlation between fructan accumulation and cold tolerance in the wheat family was recently confirmed by studies on artificially obtained wheat hexaploid lines characterized by different degrees of freezing tolerance (Yokota et al., 2015). In line with these views, it has been shown that transgenic rice plants carrying wheat fructosyltransferase (FT) genes showed an increased CS tolerance (Kawakami et al., 2008).

Galactinol synthase (GolS), the enzyme catalyzing the first step in RFO biosynthesis, is considered as a target gene of the CBF regulon (Taji et al., 2002), leading to RFO accumulation under CS. Notably, galactinol, and raffinose have also been proposed as important signals during biotic interactions (Kim et al., 2008). Another emerging point of convergence between CBFs and sugars is that AtCBF1 enhances accumulation of DELLA proteins, fundamental repressors of gibberellin (GA) signaling and positive regulators of stress responses (Claeys et al., 2014), by stimulating GA catabolism through increased expression of GA2-oxidase genes (Achard et al., 2008). Furthermore, it has been recently demonstrated that DELLAs can be specifically stabilized by Suc, but not by Glc (Li et al., 2014). DELLA proteins stimulate anthocyanin synthesis through activation of the PAP1/MYB75 transcription factor (Li et al., 2014). In general anthocyanin levels positively correlate with cold tolerance (Janska et al., 2010), probably by protecting chlorophyll from over-excitement under freezing conditions (Hannah et al., 2006).

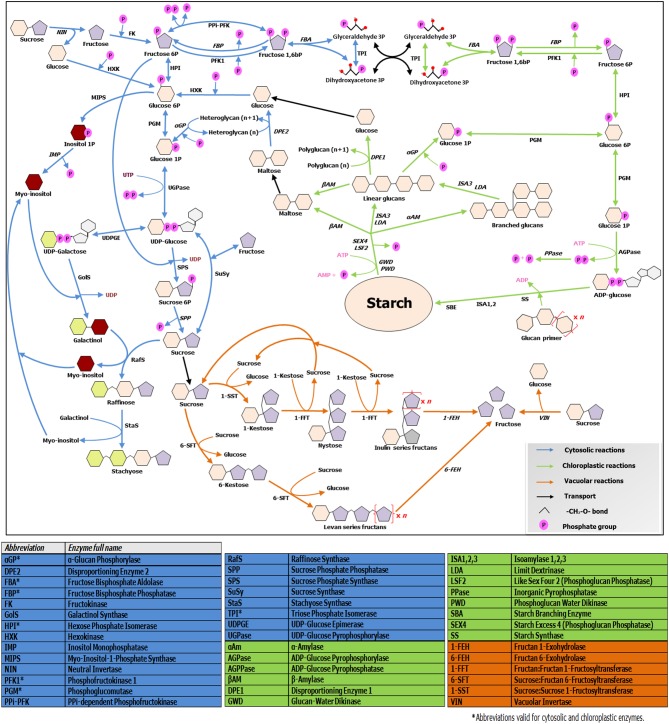

Soluble sugars levels are strictly connected with starch synthesis and breakdown dynamics, which are on their turn tightly regulated by the circadian clock (Graf et al., 2010). In turn, sugar levels have fundamental roles in entraining the clock (Haydon et al., 2013). Cold-responsive genes such as AtCBF1 show diurnal oscillations in their expression (Nakamichi et al., 2009). Moreover, expression of central clock components and diurnal regulated genes is largely influenced by CS (Miura and Furumoto, 2013), providing tight connections between the clock, metabolic adjustments and CS responses. Recently, Sicher (2011) shed light on the importance of starch dynamics during chilling responses in Arabidopsis, by comparing starch and different sugar profiles during chilling stress in light/dark conditions in wild-type and pgm1 starchless mutants. This author demonstrates that synthesis and accumulation of the two most highly induced sugars during chilling stress, maltose and raffinose, strictly depend on the presence of starch, demonstrating the intimate interconnection between RFO, sucrose, and starch metabolisms (Figure 2). It is known that both target of rapamycin (TOR) and SnRK1 kinases influence such processes (Dobrenel et al., 2013), but the exact underlying mechanisms need further exploration. Future research on crop species under CS should focus on the dynamics of all carbohydrate pools in a diurnal context, to be able to better understand the complete picture.

Figure 2.

Overview of soluble sugars, RFO, fructans and starch metabolic pathways. The scheme illustrates connections and divergences between the above mentioned pathways, taking in account their different subcellular environments. Enzymes involved in catabolic steps are written in italic. Note that only the metabolism of linear fructans is illustrated, due to space constraints. For further details, readers are referred to http://plantsinaction.science.uq.edu.au/book/export/html/121. for starch and sucrose metabolism; and to Vijn and Smeekens (1999) and Nishizawa et al. (2008) for more details on fructan and raffinose biosynthesis, respectively.

Besides the CRB signaling pathway, which is necessary but not sufficient to trigger cold acclimation, chilling, and freezing tolerance, several phytohormones also play critical roles by positively or negatively influencing cold resistance and acclimation (Thomashow, 2010; Miura and Furumoto, 2013). Among them, ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA) stand out for their well-known crosstalk with sugar signaling pathways (Gazzarrini and McCourt, 2001). Sugar signaling was also shown to take part in stress responses, and this is particularly evident when Suc-specific responses are involved (Van den Ende and El-Esawe, 2014), including the upregulation of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway (Serrano et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014), with a strong impact on the anthocyanin biosynthetic branch (Teng et al., 2005). As in development, during CS response the ABA-ethylene dynamics conserve an antagonistic nature, with CBF1 as major crosstalk point (Thomashow, 2010; Shi et al., 2012). Both ABA and Suc promote the accumulation of DELLA proteins (Guo et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2014), urging further research on possible ABA-sugar signaling synergisms under CS. Intriguingly, the accumulation of DELLA proteins is also mediated by CBF1 through posttranslational mechanisms, which seems to be required for the full activation of freezing tolerance in A. thaliana (Achard et al., 2008). Thus, it can be speculated that DELLA proteins play an important role in orchestrating ABA and sugar-induced CS responses, but this requires further research. This idea was proposed even in a much broader context by De Bruyne et al. (2014), considering DELLA proteins as pivotal modulators of the physiological balance between growth and overall (also biotic) stress responses by integrating sugar and hormonal inputs.

Thanks to their biochemical properties and availability, sugars are likely to be used by plants in counteracting the most commonly occurring adversities in their natural environment. Overall, modulation of compatible solutes, among which sugars typically represent a vast majority, may represent one of the basic mechanisms involved in multistress tolerance (Puniran-Hartley et al., 2014). Plant responses to evolutionary pressures in stressful environments led to the diversification of sugar structures and functions, as well represented by the RFO and fructan cases, among other oligosaccharides (Van den Ende, 2013). Furthermore, the ability of sugars to modulate expression of stress-related genes involved in both abiotic and biotic stress responses, such as phenylalanine ammonia lyase and pathogenesis related proteins (Herbers et al., 1996; Barau et al., 2014), testifies the high integration level of carbohydrates in cellular defensive strategies. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that sugar dynamics in the apoplastic environment need to be dissected from those occurring within the cells, a very important notion for future research (Barau et al., 2014). Recent data strongly support the involvement of invertases, key controllers of compartment-specific Suc/hexose ratios, in response to both biotic and abiotic stresses (Albacete et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014). An important goal for future research will be to unravel how invertases and other Suc metabolizing enzymes are precisely connected to the main stress signaling pathways, and in which way they influence growth/defense balances, intimately connected to TOR and SnRK1 activities. In the coming years, dissection of stress-specific signaling pathways initiated by sugar signaling will likely become one of the most exciting topics in plant physiology, disclosing new possibilities to increase multistress tolerance in crops.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

ŁPT and WVdE are supported by FWO Vlaanderen. The authors are grateful to John E. Lunn (Max Planck Institute, Potsdam-Golm) and Samuel C. Zeeman (University of Zürich) for their valuable suggestions in constructing figures. We sincerely apologize to all those colleagues whose work is not cited because of space limitations.

References

- Achard P., Gong F., Cheminant S., Alioua M., Hedden P., Genschik P. (2008). The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. Plant Cell 20, 2117–2129. 10.1105/tpc.108.058941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albacete A., Cantero-Navarro E., Grosskinsky D. K., Arias C. L., Balibrea M. E., Bru R., et al. (2014). Ectopic overexpression of the cell wall invertase gene CIN1 leads to dehydration avoidance in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 863–878. 10.1093/jxb/eru448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barau J., Grandis A., Carvalho V. M., Teixeira G. S., Zaparoli G. H. A., Scatolin do Rio M. A., et al. (2014). Apoplastic and intracellular plant sugars regulate developmental transitions in witches' broom disease of cacao. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 1325–1337. 10.1093/jxb/eru485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V., Zhu J., Zhu J. K. (2007). Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 444–451. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys H., De Bodt S., Inzé D. (2014). Gibberellins and DELLAs: central nodes in growth regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 231–239. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D., Fowler S., Fiehn O., Thomashow M. F. (2004). A prominent role for the CBF cold response pathway in configuring the low-temperature metabolome of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15243–15248. 10.1073/pnas.0406069101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couée I., Sulmon C., Gouesbet G., El Amrani A. (2006). Involvement of soluble sugars in reactive oxygen species balance and responses to oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 449–459. 10.1093/jxb/erj027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyne L., Höfte M., De Vleesschauwer D. (2014). Connecting growth and defense: the emerging roles of brassinosteroids and gibberellins in plant innate immunity. Mol. Plant 7, 943–959. 10.1093/mp/ssu050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrenel T., Marchive C., Azzopardi M., Clément G., Moreau M., Sormani R., et al. (2013). Sugar metabolism and the plant target of rapamycin kinase: a sweet operaTOR? Front. Plant Sci. 4:93. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco R. M., Regalado A., Ageorges A., Burla B. J., Bassin B., Eisenachet C., et al. (2013). RABCC1, an ATP binding cassette protein from grape berry, transports anthocyanidin 3-O-Glucosides. Plant Cell 5, 1840–1854. 10.1105/tpc.112.102152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya T., Matsuoka D., Nanmori T. (2014). Membrane rigidification functions upstream of the MEKK1-MKK2-MPK4 cascade during cold acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 588, 2025–2030. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzarrini S., McCourt P. (2001). Genetic interactions between ABA, ethylene and sugar signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 387–391. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gechev T. S., Van Breusegem F., Stone J. M., Denev I., Laloy C. (2006). Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. Bioessays 28, 1091–1101. 10.1002/bies.20493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A., Schlereth A., Stitt M., Smith A. M. (2010). Circadian control of carbohydrate availability for growth in Arabidopsis plants at night. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9458–9463. 10.1073/pnas.0914299107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Cong Y., Hussain N., Wang Y., Liu Z., Jiang L., et al. (2014a). The remodeling of seedling development in response to long-term magnesium toxicity and regulation by ABA-DELLA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1713–1726. 10.1093/pcp/pcu102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. J., Nagy R., Chen H. Y., Pfrunder S., Yu Y. C., Santelia D., et al. (2014b). SWEET17, a facilitative transporter, mediates fructose transport across the tonoplast of Arabidopsis roots and leaves. Plant Physiol. 164, 777–789. 10.1104/pp.113.232751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah M. A., Wiese D., Freund S., Fiehn O., Heyer A. G., Hincha D. (2006). Natural genetic variation of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 142, 98–112. 10.1104/pp.106.081141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon M. J., Mielczarek O., Robertson F. C., Hubbard K. E., Webb A. A. R. (2013). Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature 502, 689–692. 10.1038/nature12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbers K., Meuwly P., Metraux J. P., Sonnewald U. (1996). Salicylic acid-independent induction of pathogenesis-related protein transcripts by sugars is dependent on leaf developmental stage. FEBS Lett. 397, 239–244. 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01183-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincha D. K., Zuther E., Heyer A. G. (2003). The preservation of liposomes by raffinose family oligosaccharides during drying is mediated by effects on fusion and lipid phase transitions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1612, 172–177. 10.1016/S0005-2736(03)00116-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janska A., Marsik P., Zelenkova S., Ovesna J. (2010). Cold stress and acclimation–what is important for metabolic adjustment? Plant Biol.(Stuttg) 12, 395–405. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami A., Sato Y., Yoshida M. (2008). Genetic engineering of rice capable of synthesizing fructans and enhancing chilling tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 793–802. 10.1093/jxb/erm367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Cho S. M., Kang E. Y., Im Y. J., Hwangbo H., Kim Y. C., et al. (2008). Galactinol is a signaling component of the induced systemic resistance caused by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 root colonization. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 12, 1643–1653. 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemens P. A., Patzke K., Deitmer J., Spinner L., Le Hir R., Bellini C., et al. (2013). Overexpression of the vacuolar sugar carrier AtSWEET16 modifies germination, growth, and stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 163, 1338–1352. 10.1104/pp.113.224972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooiker M., Drenth J., Glassop D., McIntyre C. L., Xue G. P. (2013). TaMYB13-1, a R2R3 MYB transcription factor, regulates the fructan synthetic pathway and contributes to enhanced fructan accumulation in bread wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3681–3696. 10.1093/jxb/ert205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasensky J., Jonak C. (2012). Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1593–1608. 10.1093/jxb/err460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt J. (1958). Frost, drought, and heat resistance. Protoplasmologia VIII/6, 1–78 10.1007/978-3-7091-5463-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Van den Ende W., Rolland F. (2014). Sucrose induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis is mediated by DELLA. Mol. Plant 7, 570–572. 10.1093/mp/sst161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J. E. (2007). Compartmentation in plant metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 35–47. 10.1093/jxb/erl134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K., Furumoto T. (2013). Cold signaling and cold response in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 5312–5337. 10.3390/ijms14035312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nägele T., Heyer A. G. (2013). Approximating subcellular organisation of carbohydrate metabolism during cold acclimation in different natural accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 198, 777–787. 10.1111/nph.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi N., Kusano M., Fukushima A., Kita M., Ito S., Yamashino T., et al. (2009). Transcript profiling of an Arabidopsis PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATOR arrhythmic triple mutant reveals a role for the circadian clock in cold stress response. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 447–462. 10.1093/pcp/pcp004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa A., Yabuta Y., Shigeoka S. (2008). Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 147, 1251–1263. 10.1104/pp.108.122465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T., Zhu X., Duan N., Liu J. H. (2014). PtrBAM1, a beta-amylase-coding gene of Poncirus trifoliata, is a CBF regulon member with function in cold tolerance by modulating soluble sugar levels. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 2754–2767. 10.1111/pce.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshev D., Vergauwen R., Moglia A., Hideg E., Van den Ende W. (2013). Towards understanding vacuolar antioxidant mechanisms: a role for fructans? J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1025–1038. 10.1093/jxb/ers377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peukert M., Thiel J., Peshev D., Weschke W., Van den Ende W., Mock H. P., et al. (2014). Spatio-temporal dynamics of fructan metabolism in developing barley grains. Plant Cell 9, 3728–3744. 10.1105/tpc.114.130211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puniran-Hartley N., Hartley J., Shabala L., Shabala S. (2014). Salinity-induced accumulation of organic osmolytes in barley and wheat leaves correlates with increased oxidative stress tolerance: in planta evidence for cross-tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 83, 32–39. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon M., Rolland F., Sheen J. (2008). Sugar sensing and signaling. Arabidopsis Book 6:e0117. 10.1199/tab.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Y. L. (2014). Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 65, 33–67. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruelland E., Collin S. (2011). Chilling stress, in Plant Stress Physiology, ed Shabala S. (Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing; ), 94–118 10.1079/9781845939953.0094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santarius K. A. (1973). The protective effect of sugars on chloroplast membranes during temperature and water stress and its relationship to frost, desiccation and heat resistance. Planta 113, 105–114. 10.1007/BF00388196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T., Keller F. (2009). Raffinose in chloroplasts is synthesized in the cytosol and transported across the chloroplast envelope. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 2174–2182. 10.1093/pcp/pcp151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M., Kanehara K., Torres M., Yamada K., Tintor N., Kombrinket E., et al. (2012). Repression of sucrose/ultraviolet B light-induced flavonoid accumulation in microbe-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 408–422. 10.1104/pp.111.183459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Tian S., Hou L., Huang X., Zhang X., Guo H., et al. (2012). Ethylene signaling negatively regulates freezing tolerance by repressing expression of CBF and type-A ARR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 2578–2595. 10.1105/tpc.112.098640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicher R. (2011). Carbon partitioning and the impact of starch deficiency on the initial response of Arabidopsis to chilling temperatures. Plant Sci. 181, 167–176. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M., Hurry V. (2002). A plant for all seasons: alterations in photosynthetic carbon metabolism during cold acclimation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 199–206. 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00258-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanova S., Geuns J., Hideg E., Van den Ende W. (2011). The food additives inulin and stevioside counteract oxidative stress. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 207–214. 10.3109/09637486.2010.523416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G., Hauser H. (1986). Stabilization of lipid bilayer vesicles by sucrose during freezing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 2422–2426. 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Yang D. L., Kong Y., Chen Y., Li X. Z., Zeng L. J., et al. (2014). Sugar homeostasis mediated by cell wall invertase GRAIN INCOMPLETE FILLING 1 (GIF1) plays a role in pre-existing and induced defence in rice. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 161–173. 10.1111/mpp.12078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taji T., Ohsumi C., Iuchi S., Seki M., Kasuga M., Kobayashi M., et al. (2002). Important roles of drought- and cold-inducible genes for galactinol synthase in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 29, 417–426. 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng S., Keurentjes J., Bentsink L., Koornneef M., Smeekens S. (2005). Sucrose-specific induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis requires the MYB75/PAP1 gene. Plant Physiol. 139, 1840–1852. 10.1104/pp.105.066688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow M. F. (2010). Molecular basis of plant cold acclimation: insights gained from studying the CBF cold response pathway. Plant Phys. 54, 571–577. 10.1104/pp.110.161794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valluru R., Lammens W., Claupein W., Van den Ende W. (2008). Freezing tolerance by vesicle-mediated fructan transport. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 409–414. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W. (2013). Multifunctional fructans and raffinose family oligosaccharides. Front. Plant Sci. 4:247. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W., El-Esawe S. K. (2014). Sucrose signaling pathways leading to fructan and anthocyanin accumulation: a dual function in abiotic and biotic stress responses? Environ. Exp. Bot. 108, 4–13 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W., Valluru R. (2009). Sucrose, sucrosyl oligosaccharides, and oxidative stress: scavenging and salvaging? J. Exp. Bot. 60, 9–18. 10.1093/jxb/ern297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereyken I. J., Chupin V., Demel R. A., Smeekens S., De Kruijff B. (2001). Fructans insert between the headgroups of phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1510, 307–320. 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00363-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijn I., Smeekens S. (1999). Fructan: more than a reserve carbohydrate? Plant Physiol. 120, 351–360. 10.1104/pp.120.2.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormit A., Trentmann O., Feifer I., Lohr C., Tjaden J., Meyer S., et al. (2006). Molecular identification and physiological characterization of a novel monosaccharide transporter from Arabidopsis involved in vacuolar sugar transport. Plant Cell 18, 3476–3490. 10.1105/tpc.106.047290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota H., Iehisa J. C., Shimosaka E., Takumi S. (2015). Line differences in Cor/Lea and fructan biosynthesis-related gene transcript accumulation are related to distinct freezing tolerance levels in synthetic wheat hexaploids. J. Plant Physiol. 176, 78–88. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Abe J., Moriyama M., Kuwabara T. (1998). Carbohydrate levels among winter wheat cultivars varying in freezing tolerance and snow mold resistance during autumn and winter. Phys. Plant 103, 8–16. [Google Scholar]