Abstract

Several members of the genus Burkholderia are prominent pathogens. Infections caused by these bacteria are difficult to treat because of significant antibiotic resistance. Virtually all Burkholderia species are also resistant to polymyxin, prohibiting use of drugs like colistin that are available for treatment of infections caused by most other drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Despite clinical significance and antibiotic resistance of Burkholderia species, characterization of efflux pumps lags behind other non-enteric Gram-negative pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although efflux pumps have been described in several Burkholderia species, they have been best studied in Burkholderia cenocepacia and B. pseudomallei. As in other non-enteric Gram-negatives, efflux pumps of the resistance nodulation cell division (RND) family are the clinically most significant efflux systems in these two species. Several efflux pumps were described in B. cenocepacia, which when expressed confer resistance to clinically significant antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines. Three RND pumps have been characterized in B. pseudomallei, two of which confer either intrinsic or acquired resistance to aminoglycosides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, trimethoprim, and in some instances trimethoprim+sulfamethoxazole. Several strains of the host-adapted B. mallei, a clone of B. pseudomallei, lack AmrAB-OprA, and are therefore aminoglycoside and macrolide susceptible. B. thailandensis is closely related to B. pseudomallei, but non-pathogenic to humans. Its pump repertoire and ensuing drug resistance profile parallels that of B. pseudomallei. An efflux pump in B. vietnamiensis plays a significant role in acquired aminoglycoside resistance. Summarily, efflux pumps are significant players in Burkholderia drug resistance.

Keywords: Burkholderia, antibiotics, resistance, efflux pump, adaptation

The Genus Burkholderia

The genus Burkholderia comprises metabolically diverse and adaptable Gram-negative bacteria that are able to thrive in different, often adversarial, environments. Their metabolic versatility and adaptability is in part due to the coding capacity provided by large (7–9 Mb) genomes consisting of several chromosomes and in some species, e.g., Burkholderia cenocepacia, plasmids (Holden et al., 2004, 2009; Agnoli et al., 2012). Many members of the genus are clinically significant pathogens with renowned virulence potential (Tegos et al., 2012) and drug resistance (Burns, 2007). In contrast to most other Gram-negative pathogens, Burkholderia species are intrinsically polymyxin resistant and therefore colistin cannot be used as drug of last resort (Loutet and Valvano, 2011). Despite clinical significance and recognized antibiotic resistance of Burkholderia species, characterization of efflux pumps lags significantly behind other non-enteric Gram-negative pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Nikaido and Pages, 2012). Many Burkholderia efflux systems have homologs in other Gram-negatives, including A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, and it is now generally believed that the multidrug resistance exhibited by these opportunistic pathogens is largely attributable to the existence of similar efflux pumps in these organisms (Poole, 2001; McGowan, 2006). As with other Gram-negative bacteria, the relative roles that individual efflux pumps play in intrinsic or acquired antibiotic resistance in the respective Burkholderia species are in many instances difficult to discern for various reasons: (1) a subset of the pumps found in any organism usually exhibits a considerable degree of substrate promiscuity, i.e., they recognize and extrude chemically and structurally diverse compounds, which leads to similar multidrug resistance profiles; (2) many of the efflux systems are not expressed at significant levels in wild-type strains under laboratory conditions and there exists a significant knowledge gap regarding the environmental conditions under which efflux genes are expressed; and (3) well characterized clinical or laboratory isolates expressing or lacking the respective efflux pumps often do not exist or are difficult to obtain (Mima and Schweizer, 2010; Coenye et al., 2011; Biot et al., 2013; Buroni et al., 2014). In this review we will summarize the current state of knowledge of efflux pumps and their roles in antibiotic resistance in the genus Burkholderia, which have been characterized to various degrees in a few representative organisms.

Burkholderia cepacia Complex

The Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) currently comprises 17 closely related species (Mahenthiralingam et al., 2005; Vanlaere et al., 2009; Vandamme and Dawyndt, 2011). Some BCC members exhibit beneficial aspects such as use in biocontrol, a practice that has since been abandoned because of the risk of infection of compromised individuals (Kang et al., 1998). Many are opportunistic pathogens, being particularly problematic for cystic fibrosis patients and immune compromised individuals. B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans account for 85% of all BCC infections (Drevinek and Mahenthiralingam, 2010). BCC infections are difficult to treat because of intrinsic antibiotic resistance and persistence in the presence of antimicrobials (Golini et al., 2004; Peeters et al., 2009; Rajendran et al., 2010; Jassem et al., 2011). B. vietnamiensis belongs to the BCC group and sporadically infects cystic fibrosis patients (Jassem et al., 2011).

Burkholderia pseudomallei

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a saprophyte and opportunistic pathogen endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of the world, and recent studies suggest that is more widespread than previously thought (Wiersinga et al., 2006, 2012, 2015; Currie et al., 2010). Since the U.S. anthrax attacks in 2001 the bacterium has received increasing attention because of its biothreat potential (Cheng et al., 2005), a history dating back to its use with malicious intent in a Sherlock Holmes short story (Vora, 2002). In the U.S. it is a strictly regulated Tier 1 select agent, which must be handled in approved biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratories. The bacterium is the etiologic agent of melioidosis, a difficult-to-treat multifacteted disease (Wiersinga et al., 2006, 2012). The disease affects at-risk patients, including those suffering from cystic fibrosis (Schulin and Steinmetz, 2001; Holland et al., 2002), non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (Price et al., 2013), and diabetes (Simpson et al., 2003). B. pseudomallei infections are recalcitrant to antibiotic therapy because of the bacterium’s intrinsic resistance due to expression of resistance determinants such as β-lactamase and efflux pumps, as well as contributing factors such as both intracellular and biofilm lifestyles (Schweizer, 2012b).

Burkholderia mallei

Burkholderia mallei is an obligate zoonotic pathogen and the etiologic agent of glanders, which has been used as a bioweapon (Cheng et al., 2005; Whitlock et al., 2007). This bacterium likely diverged from B. pseudomallei upon introduction into an animal host approximately 3.5 million years ago (Losada et al., 2010; Song et al., 2010). The ensuing in-host evolution through massive expansion of insertion (IS) elements, IS-mediated gene deletion, and genome rearrangement, and prophage elimination is likely also responsible for the generally increased antibiotic susceptibility of B. mallei when compared to B. pseudomallei, presumably due to inactivation of resistance determinants (Nierman et al., 2004).

Burkholderia thailandensis

Burkholderia thailandensis is closely related to B. pseudomallei (Brett et al., 1998). Although B. thailandensis has sporadically been shown to cause human disease (Glass et al., 2006), it is generally considered non-pathogenic and has often been used as a surrogate for antimicrobial compound and vaccine efficacy studies because the bacterium can be handled at BSL-2. Some strains are more closely related to B. pseudomallei than others. For instance, unlike the widely used B. thailandensis prototype strain E264 (Brett et al., 1998), strain E555 expresses the same capsular polysaccharide as B. pseudomallei (Sim et al., 2010). Since capsular polysaccharide is a potent immunogen this similarity was exploited in a vaccine study, which showed that immunization with live cells of this avirulent strain protects mice from challenge with a virulent B. pseudomallei strain (Scott et al., 2013).

Burkholderia cenocepacia

Efflux Pumps and Drug Resistance

Early reports provided mostly indirect evidence that B. cenocepacia efflux pumps play a role in drug efflux. The synergy between reduced outer membrane permeability and efflux was cited as a common theme of the increased resistance that non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria like A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and B. (ceno)cepacia display (Hancock, 1998). An analysis of the DsbA–DsbB disulfide bond formation system revealed that dsbA and dsbB mutation resulted increased susceptibilities to a variety of antibiotics (Hayashi et al., 2000). This led to the conclusion that the DsbA–DsbB system might be involved in the formation of a multidrug resistance system. Another early report described an outer membrane lipoprotein involved in multiple antibiotic (chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin) resistance (Burns et al., 1996). This protein, OpcM, is the outer membrane channel of an efflux pump of the resistance nodulation cell division (RND) family that was subsequently named CeoAB-OpcM, which was shown to be inducible by salicylate and chloramphenicol (Nair et al., 2004). Efflux was also shown early on to play a role in fluoroquinolone resistance (Zhang et al., 2001).

Genome analysis and homology searches led to identification of an additional 14 open reading frames encoding putative components RND family efflux pumps (Guglierame et al., 2006). A summary of pertinent features of at least partially characterized B. cenocepacia RND efflux pumps and their relationships to RND systems in other Burkholderia species is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Partially characterized resistance nodulation cell division (RND) efflux pumps in Burkholderia species.

| Species | Efflux pump | Gene names | Gene annotation | Major substrates | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | |||||

| RND-1 | NA | BCAS0591–BCAS0593 | Non-detectable | Buroni et al. (2009) | |

| RND-3 | NA1 | BCAL1674–BCAL1676 | Nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, tobramycin, chlorhexidine3 | Buroni et al. (2009, 2014), Coenye et al. (2011) | |

| RND-4 | NA2 | BCAL2820–BCAL2822 | Aztreonam, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tobramycin | Bazzini et al. (2011b) | |

| RND-8 | NA | BCAM0925–BCAM0927 | Tobramycin3 | Buroni et al. (2014) | |

| RND-9 | NA | BCAM1945–BCAM1947 | Tobramycin3, chlorhexidine3 | Coenye et al. (2011), Buroni et al. (2014) | |

| RND-10 | ceoAB-opcM4 | BCAM2551–BCAM2549 | Chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim | Nair et al. (2004) | |

| B. pseudomallei | |||||

| AmrAB-OprA | amrAB-oprA | BPSL1804–BPSL1802 | Aminoglycosides, macrolides, cethromycin | Moore et al. (1999), Mima et al. (2011) | |

| BpeAB-OprB | bpeAB-oprB | BPSL0814–BPSL0816 | Chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, tetracyclines5 | Chan et al. (2004), Mima and Schweizer (2010) | |

| BpeEF-OprC | bpeEF-oprC | BPSS0292–BPSS0294 | Chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, trimethoprim6 | Kumar et al. (2006), Schweizer (2012a,b) | |

| B. thailandensis | |||||

| AmrAB-OprA | amrAB-oprA | BTH_I2445–BTH_I2443 | Aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines | Biot et al. (2013) | |

| BpeAB-OprB | bpeAB-oprB | BTH_I0680–BTH_I0682 | Tetracyclines | Biot et al. (2013) | |

| BpeEF-OprC | bpeEF-oprC | BTH_II2106–BTH_II2104 | Chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Biot et al. (2011, 2013) | |

| B. vietnamiensis | |||||

| AmrAB-OprM | amrAB-oprM | Bcep1808_1574–Bcep1808_1576 | Aminoglycosides | Jassem et al. (2014) |

NA, not applicable

1Corresponds to B. pseudomallei amrAB-oprA

2Corresponds to B. pseudomallei bpeAB-oprB

3Sessile (biofilm grown) cells only

4Corresponds to B. pseudomallei bpeEF-oprC

5Low-level resistance in de-repressed (ΔbpeR) strains

6High-level resistance in regulatory mutants, e.g., bpeT carboxy-terminal mutations

Expression of one of these, orf2, in Escherichia coli conferred resistance to several antibiotics (Guglierame et al., 2006). The roles of several RND transporters – RND-1, RND-3, and RND-4 – in intrinsic B. cenocepacia drug resistance was subsequently assessed by mutational analyses, which showed that RND-3 and RND-4, but not RND-1, contribute to B. cenocepacia’s intrinsic resistance to antibiotics and other inhibitory compounds (Buroni et al., 2009). A subsequent study comparing RND-4 and RND-9 single and double mutants confirmed the role that RND-4 plays in B. cenocepacia’s antibiotic resistance and also showed that RND-9 contributed only marginally to resistance (Bazzini et al., 2011b). Completion of the strain J2315 genome sequence showed that it encodes 16 RND efflux systems, which provides evidence for the biological relevance of these transporters in this bacterium and also enables global analyses of RND pump expression (Holden et al., 2009; Perrin et al., 2010; Bazzini et al., 2011a; Buroni et al., 2014). For example, deletion of the 16 putative RND operons from B. cenocepacia strain J2315 showed that these pumps play differential roles in the drug resistance of sessile (biofilm) and planktonic cells. These studies revealed that: (1) RND-3 and RND-4 play important roles in resistance to various antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin and tobramycin, in planktonic populations; (2) RND-3, RND-8, and RND-9 protect from the antimicrobial effects of tobramycin in biofilm cells; and (3) RND-8 and RND-9 do not play a role in ciprofloxacin resistance (Buroni et al., 2014). An emerging theme from these studies is that RND-3 seems to play a major role in B. cenocepacia’s intrinsic drug resistance. It was suggested that mutations in the RND-3 regulator-encoding gene may be responsible for this pump’s prevalent overexpression and accompanying high-level antibiotic resistance in clinical BCC isolates (Tseng et al., 2014).

Studies aimed at assessing chlorhexidine mechanisms in B. cenocepacia J2315 confirmed the differential roles that RND pumps play in biofilm versus planktonically grown cells. RND-4 contributed to chlorhexidine resistance in planktonic cells, whereas RND-3 and RND-9 played a role in chlorhexidine resistance in sessile cells (Coenye et al., 2011). Mutational analyses of 2-thiopyridine resistant mutants showed that RND-4 confers resistance to an anti-tubercular 2-thiopyridine derivative (Scoffone et al., 2014). The involvement of efflux pumps in tigecycline resistance was inferred from the potentiating effects of the efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) MC-207,110 on tigecycline’s anti-B. cenocepacia activity (Rajendran et al., 2010).

Efflux pumps belonging to other families may also contribute to B. cenocepacia’s drug resistance. Experiments with an immunodominant antigen in cystic fibrosis patients infected with B. cenocepacia identified a drug efflux pump, BcrA, which is a member of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS). It was shown to confer tetracycline and nalidixic acid resistance when expressed in E. coli (Wigfield et al., 2002). Upregulation of an efflux pump resulted in resistance to the phosphonic acid antibiotic fosfidomycin (Messiaen et al., 2011). This pump is a homolog of Fsr, a member of the MFS, which was previously shown to confer fosmidomycin resistance on E. coli (Fujisaki et al., 1996; Nishino and Yamaguchi, 2001).

Other Functions of B. cenocepacia RND Efflux Pumps

As with other Gram-negative bacteria, the function of B. cenocepacia efflux pumps extends beyond antibiotic resistance. In B. cenocepacia, these systems are involved in modulation of virulence-associated traits such as quorum sensing, biofilm formation, chemotaxis, and motility, as well as general physiological functions (Buroni et al., 2009; Bazzini et al., 2011a,b). A proteomic analysis of the effects of RND-4 gene deletion revealed about 70 differentially expressed proteins, most of which were associated with cellular functions other than drug resistance. This suggests that RND-4 plays a more general role in B. cenocepacia’s biology (Gamberi et al., 2013). Aside from the key role that efflux, especially RND-mediated efflux, plays in adaptation to antibiotic exposure (Bazzini et al., 2011b; Sass et al., 2011; Tseng et al., 2014), survival of Burkholderia species in various niche environments and accompanying conditions, e.g., the cystic fibrosis airways (Mira et al., 2011), marine habitats (Maravic et al., 2012), oxygen levels (Hemsley et al., 2014), exposure to noxious chemicals (Rushton et al., 2013), and other ecological niches (Liu et al., 2015), involves to various degrees changes in efflux pump expression.

Burkholderia pseudomallei

Efflux Pumps and Drug Resistance

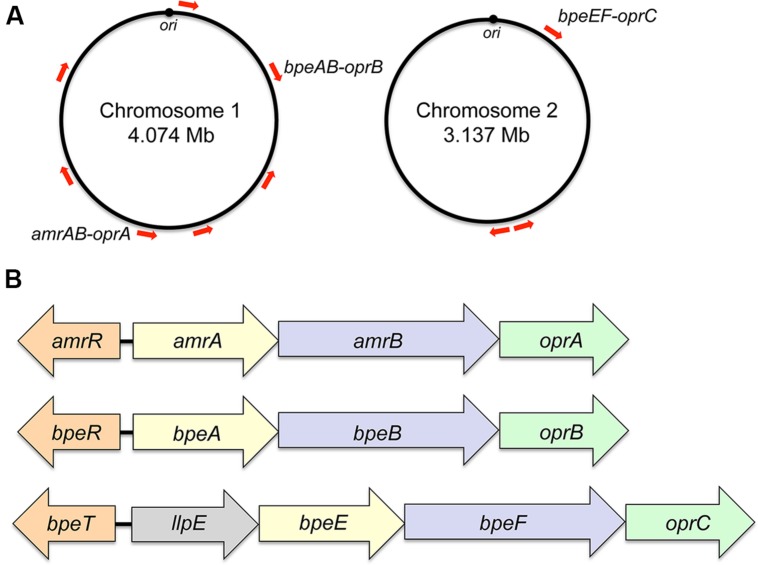

Initially, the presence of genomic DNA sequences in B. pseudomallei that hybridize with the multidrug resistance efflux gene oprM of P. aeruginosa was interpreted as evidence that efflux-mediated multidrug efflux systems may also be present in B. pseudomallei (Bianco et al., 1997). A recent survey of documented B. pseudomallei antibiotic resistance mechanisms indeed showed that efflux is the dominant mechanism affecting most classes of antibiotics (Schweizer, 2012b). Sequenced B. pseudomallei genomes encode numerous efflux systems, but as with other non-enteric bacteria only RND pumps have to date been shown to confer resistance to clinically significantly antibiotics. The K96243 and other B. pseudomallei genomes encode at least 10 RND systems, seven of which are encoded by chromosome 1 and three by chromosome 2 (Holden et al., 2004; Figure 1A). Although RND operon distribution is conserved amongst diverse B. pseudomallei strains, locations on the respective chromosomes may vary because of chromosome rearrangements. Bioinformatic analyses indicate that not all of the RND operons encode drug efflux pumps. For instance, one system seems to encode components of a general secretion (Sec) system. Although the presence of many RND systems can be detected in clinical and environmental isolates at the transcriptional (Kumar et al., 2008) and protein level (Schell et al., 2011), this expression is not necessarily linked to increased drug resistance. Meaningful studies to address their function are complicated because isogenetic progenitor and/or comparator strains are generally not available. Further hindering efflux pump characterization are select agent guidelines, which restrict certain methods, such as selection of spontaneous drug resistant mutants that may display altered efflux expression profiles. These investigations are now facilitated by the availability of several B. pseudomallei strains, for instance Bp82 (Propst et al., 2010), which are excluded from select agent rulings. To date three RND drug efflux pumps – AmrAB-OprA, BpeAB-OprB, and BpeEF-OprC – have been characterized in some detail (Figure 1B). There is evidence that small molecule compounds such as MC-207,110, phenothiazine antipsychotics, and antihistaminic drugs like promazine can be used to potentiate antibiotic efficacy, primarily by inhibition of RND efflux pumps (Chan et al., 2007b).

FIGURE 1.

Genomic location and operon organization of Burkholderia pseudomallei resistance nodulation cell division (RND) efflux pumps. (A) Chromosomal locations of RND efflux operons in strain K96243. Red arrows indicate the approximate locations and transcriptional orientations of RND operons on chromosomes 1 and 2. Operons encoding characterized efflux pumps are labeled. Although RND operon distribution is conserved amongst diverse B. pseudomallei strains, locations on the respective chromosomes may vary because of chromosome rearrangements. The origins of replication (ori) in the two strain K96243 chromosomes are marked. Their respective locations on the chromosomes of other strains may vary because of chromosome rearrangements. (B) Transcriptional organization of characterized RND operons. The genes encoding the membrane fusion proteins (amrA, bpeA, bpeE), RND transporter (amrB, bpeB, bpeF) and outer membrane protein channel (oprA, oprB, oprC) are color-coded. The bpeE–bpeF–oprC genes are in the same operon as llpE, which is annotated as a putative lipase/carboxyl esterase. LlpE is not required for BpeEF-OprC efflux pump function. Orthologs of LlpE are present in all annotated operons that encode bpeE–bpeF–oprC orthologs. The amrR and bpeR genes encode repressors of amrAB-oprA and bpeAB-oprB, respectively. The bpeT gene encodes a LysR-type transcriptional regulator of llpE-bpeE-bpeF-oprC.

AmrAB-OprA

The AmrAB-OprA efflux pump was the first efflux pump described in B. pseudomallei (Moore et al., 1999). It is responsible for this organism’s high-level intrinsic aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance (Moore et al., 1999; Viktorov et al., 2008). Rare (∼1 in 1,000) naturally occuring aminoglycoside susceptible B. pseudomallei isolates have previously been identified (Trunck et al., 2009; Podin et al., 2014). They do not express the AmrAB-OprA pump either due to regulatory mutations (Trunck et al., 2009), point mutations affecting the AmrB RND transporter amino acid sequence (Podin et al., 2014), or because the entire amrAB-oprM operon is missing due to a genomic deletion (Trunck et al., 2009). Although the AmrAB-OprA efflux pump is expressed in prototype strains, exposure to antimicrobials can select for unknown mutations that cause its over-expression resulting in increased resistance. For instance, prototype strain 1026b is moderately susceptible [minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) 4–8 μg/mL] to the ketolide cethromycin and exposure to this compound readily selects for highly resistant (MIC > 128 μg/mL) derivatives due to AmrAB-OprA over-expression (Mima et al., 2011). To date, AmrAB-OprA expression is the sole reported aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance mechanism observed in B. pseudomallei.

AmrAB is closely related to P. aeruginosa MexXY, which is expressed in some aminoglycoside resistant mutants and together with OprM constitutes a functional effux pump (Mine et al., 1999; Sobel et al., 2003; Morita et al., 2012). MexXY associates with the mexAB-oprM encoded OprM outer channel protein because the mexXY operons of most P. aeruginosa strains do not encode a cognate outer mebrane channel protein. However, some strains, e.g., P. aeruginosa PA7, encode a mexAB-oprA operon akin and functionally equivalent to B. pseudomallei amrAB-oprA (Morita et al., 2012).

BpeAB-OprB

The BpeAB-OprB efflux pump was first described in strain KHW from Singapore (Chan et al., 2004) and subsequently characterized in Thai strain 1026b (Mima and Schweizer, 2010). It is not significantly expressed in wild-type strains. BpeAB-OprB expression is regulated by BpeR and bpeR mutants exhibit low-level chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, and macrolide resistance (Chan et al., 2004; Chan and Chua, 2005; Mima and Schweizer, 2010). Although the original studies with strain KHW indicated a role of BpeAB-OprB in aminoglycoside resistance (Chan et al., 2004), these results could not be confirmed with strain 1026b (Mima and Schweizer, 2010). At present, the observed differences in BpeAB-OprB substrate spectrum between strains KHW and 1026b are not understood. Because of the low levels of resistance bestowed by BpeAB-OprB and naturally occuring antibiotic resistant BpeAB-OprB over-expressing mutants have yet to be identified, the clinical significance of this pump remains unclear.

Although BpeAB-OprB is related to P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM (Poole et al., 1993; Li et al., 1995; Mima and Schweizer, 2010), the respective features are quite divergent. While P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM is widely expressed and responsible for this bacterium’s intrinsic resistance to numerous antibacterial compounds (Poole et al., 1993; Li et al., 1995; Poole, 2001), B. pseudomallei BpeAB-OprB is not widely expressed and does seem to play only a minor role in this bacterium’s resistance to antimicrobials.

BpeEF-OprC

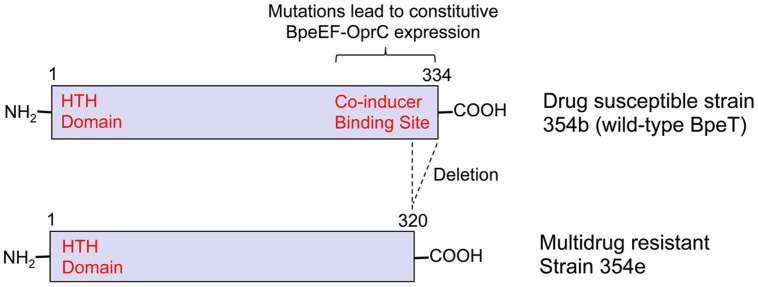

BpeEF-OprC was first identified as a chloramphenicol and trimethoprim efflux pump by expression in an efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa strain (Kumar et al., 2006). This pump is not expressed in B. pseudomallei wild-type strains, but only regulatory mutants. For instance, it is constitutively expressed in naturally occuring bpeT mutants (Hayden et al., 2012; Figure 2). When expressed, BpeEF-OprC confers high-level resistance to chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim. It is responsible for widespread trimethoprim resistance in clinical and environmental B. pseudomallei isolates (Podnecky et al., 2013). Pump expression is inducible by some pump substrates, which when present at sub MIC levels may lead to cross-resistance with other pump substrates (Schweizer, 2012a).

FIGURE 2.

The transcriptional regulator BpeT and locations of mutations causing multidrug resistance due to BpeEF-OprC expression. The figure illustrates the cause of BpeEF-OprC expression leading to a multidrug resistance phenotype due to bpeT mutations by comparing a prototype strain, in this instance a primary melioidosis isolate (strain 354b; Top), and a relapse isolate (strain 354e; Bottom). Strain 354b (Top) expresses wild-type BpeT that exhibits the typical LysR-type regular organization with an amino-terminal helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain and a co-inducer binding site located within the carboxy-terminal half. Point mutations located within the latter domain result in constitutive BpeEF-OprC efflux pump expression. Strain 354e (Bottom) expresses BpeEF-OprC constitutively due to deletion of the last 14 native bpeT codons as a consequence of a 800 kb inversion affecting chromosome 2 (Hayden et al., 2012).

BpeEF-OprC is related to P. aeruginosa MexEF-OprN (Koehler et al., 1997), which shares properties such as substrate profiles and selection of pump-expressing regulatory mutants by chloramphenicol as previously demonstrated with both P. aeruginosa MexEF-OprN (Koehler et al., 1997) and B. thailandensis BpeEF-OprC (Biot et al., 2011).

Other Functions of B. pseudomallei Efflux Pumps

Quorum sensing is an important determinant of virulence factor regulation in bacteria. Numerous studies with P. aeruginosa indicate the involvement of several RND pumps in quorum sensing and thus several virulence traits by being involved in transport of cell-to-cell signaling molecules and their inhibitors (Evans et al., 1998; Pearson et al., 1999; Koehler et al., 2001; Aendekerk et al., 2005; Hirakata et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2009). At least one efflux pump regulator, MexT, modulates expression of virulence factors, albeit independent of the function of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump whose expression it regulates (Tian et al., 2009). A P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM deletion strain is also compromised in its ability to invade Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (Hirakata et al., 2009). Based on these findings with P. aeruginosa, several studies with B. pseudomallei explored the effects of efflux on quorum sensing and virulence. Studies with strain KHW showed that the BpeAB-OprB efflux pump was required: (1) for the secretion of the acyl homoserine lactones produced by this strains quorum-sensing systems (Chan et al., 2007a); and (2) secretion of several virulence-associated determinants, including siderophore and biofilm formation (Chan and Chua, 2005), but these observations could not be confirmed with strain 1026b (Mima and Schweizer, 2010). Cell invasion of and cytotoxicity toward human A549 lung epithelial and THP-1 macrophage cell were signifianctly reduced in a KHW BpeAB-deficient strain (Chan and Chua, 2005). Adherence to A549 cells and virulence in the BALB/c mouse intranasal infection model were not affected in the AmrAB-OprA deficient Bp340 mutant, a derivative of strain 1026b (Campos et al., 2013). BALB/c mouse intranasal infection studies also showed that in addition to AmrAB-OprA, BpeAB-OprB, and BpeEF-OprC were not required for virulence (Propst, 2011; Schweizer, 2012a). The AmrAB-OprA efflux pump is also not required for efficient killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by B. pseudomallei (O’Quinn et al., 2001). The BpeAB-OprB pump has been implicated in being involved in spermidine homeostasis in strain KHW with exogenous spermidine and N-acetylspermidine activating bpeA transcription (Chan and Chua, 2010).

Efflux Pumps in other Burkholderia Species

Burkholderia mallei

In part due to ongoing in host evolution of this obligate pathogen, B. mallei is generally more susceptible to antimicrobials than its progenitor B. pseudomallei. For instance, many B. mallei strains are susceptible to aminoglycosides. In the ATCC 23344 prototype strain this susceptibility results from a 50 kb chromosomal deletion encompassing the amrAB-oprA operon (Nierman et al., 2004). Strains NCTC10229 and NCTC10247 are likely aminoglycoside susceptible because only remnants of the amrAB-oprA operon are present (Winsor et al., 2008). Genes and operons encoding other efflux pumps, including BpeAB-OprB and BpeEF-OprC, are present but whether they encode functional efflux systems remains remains to be established.

Burkholderia thailandensis

One study indicated the presence of an MFS efflux pump, with an associated regulatory protein of the multiple antibiotic resistance regulator (MarR) family (Grove, 2010). However, expression of the efflux pump was only responsive to urate, xanthine, and hypoxanthine and thus the significance of this transporter in B. thailandensis’ antibiotic resistance, if any, is unclear.

In contrast, the contributions of RND pumps to this bacterium’s antibiotic resistance have been established. It was shown that chloramphenicol exposure selects for expression of an RND efflux pump, BpeEF-OprC, that also extrudes fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, and trimethoprim (Biot et al., 2011). Doxycycline selection resulted in mutants that either over-expressed AmrAB-OprA or BpeEF-OprC, and exhibited the multidrug resistance profiles associated with expression of these efflux pumps (Biot et al., 2013). Mutational analysis of these mutants suggested that BpeAB-OprB could at least partially substitute for absence of either AmrAB-OprA or BpeEF-OprC. Unlike other Gram-negative bacteria, cell envelope properties, efflux pump repertoire, and resulting drug resistance profile make B. thailandensis suitable as a B. pseudomallei BSL-2 surrogate for drug efficacy studies (Schweizer, 2012c).

Burkholderia vietnamiensis

Transposon mutagenesis studies aimed at identification of polymyxin B susceptible mutants identified a gene encoding a NorM multidrug efflux protein (Fehlner-Gardiner and Valvano, 2002). While norM expression in an E. coli acrAB deletion mutant complemented its norfloxacin susceptibility, its inactivation in B. vietnamiensis only affected susceptibility to polymyxin but not other antibiotics.

Unlike other Burkholderia species, including most BCC members, the majority of environmental and clinical B. vietnamiensis isolates are aminoglycoside susceptible (Jassem et al., 2011). Aminoglycoside resistance as a result of chronic infection or in vitro exposure to aminoglycosides is the result of the AmrAB-OprM efflux pump, which is most likely a homolog of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis AmrAB-OprA (Jassem et al., 2011, 2014). Of note is the observation that efflux pump expression in mutants that acquired resistance during infection was due to missense mutations in the amrAB-oprM regulator amrR, but not those mutants derived from antibiotic pressure in vivo (Jassem et al., 2014).

Burkholderia Efflux Pump Mutants as Experimental Tools

The high-level intrinsic antibiotic resistance of many Burkholderia species complicates their genetic manipulation, use in studies of intracellular bacteria with the aminoglycoside protection assay, and drug efficacy studies. It has been shown that efflux-compromised mutants of B. cenocepacia and B. pseudomallei greatly facilitate genetic manipulation of these species, as well as cell invasion studies using the aminoglycoside protection assay (Dubarry et al., 2010; Hamad et al., 2010; Campos et al., 2013). Efflux-compromised strains of B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei strains have also proved useful for study of the efflux propensity of novel antimicrobial compounds (Liu et al., 2011; Mima et al., 2011; Teng et al., 2013; Cummings et al., 2014).

Conclusion

Burkholderia species are well adapted to life in diverse, often adversarial, environments including those containing antimicrobials. This adaptation is facilitated by large genomes that bestow on the bacteria the ability to either degrade or expel noxious chemicals. As a result, opportunistic infections by pathogenic members of this species are difficult to treat because of intrinsic antibiotic resistance and persistence in the presence of antimicrobials. Resistance is in large part attributable to efflux pump expression, mostly members of the RND family. While the last decade has seen significant progress in study of drug efflux in Burkholderia species, progress still lags significantly behind other opportunistic pathogens, e.g., P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, where efflux pumps also play significant roles in intrinsic and acquired drug resistance.

There are some unique aspects of efflux systems in Burkholderia species that are without parallel and studies of these may shed light on unique physiological functions of efflux pumps in these organisms. For instance, the first gene in the bpeEF-oprC operon, llpE, is co-transcribed with the genes encoding the BpeEF-OprC efflux pump components (Nair et al., 2004, 2005). Its deletion neither affects efflux pump function nor specificity for known antibiotic substrates. It is highly conserved throughout the Burkholderia genus and found in all sequenced genomes (Winsor et al., 2008). Based on homology, LlpE probably is an enzyme of the alpha/beta hydrolase family, recently annotated as a putative lipase/carboxyl esterase, and its conservation throughout the genus suggests an adaptation or survival benefit in a niche environment. The unique association of this enzyme with BpeEF-OprC and its role in Burkholderia biology warrant further studies of this enzyme.

When reviewing the B. cenocepacia efflux pump literature it becomes evident that efflux pump nomenclature in this species, especially that of the RND family is non-uniform and confusing (for instance CeoAB-OpcM, RND-1 to RND-16, BCA gene names, Mex1, orf, etc.), which makes comparisons with other Gram-negative bacteria unnecessarily cumbersome. As with other Gram-negative bacteria, the nomenclature initiated in B. cenocepacia by Dr. Jane Burns’ laboratory in the early 2000s, i.e., CeoAB-OpcM (Nair et al., 2004), would make the most sense and it is a pity that it was not followed in subsequent studies.

Author Contributions

NP, KR, and HS contributed to all aspects of the work, including, but not limited to, conception and design, acquisition and analysis of data, writing the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of several talented graduate students (Katie Propst, Kyoung-Hee Choi, Lily Trunck, Carolina Lopez) and postdocs (Takehiko Mima, Ayush Kumar, Nawarat Somprasong) to efflux pump research performed in the Schweizer laboratory. We acknowledge Dr. Hillary Hayden from the University of Washington for providing sequence information on B. pseudomallei strains 354b and 354e. Work in the HPS laboratory was supported by grant AI065357 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and contract HDTRA1-08-C-0049 from the United States Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

References

- Aendekerk S., Diggle S. P., Song Z., Hoiby N., Cornelis P., Williams P., et al. (2005). The MexGHI-OpmD multidrug efflux pump controls growth, antibiotic susceptibility and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via 4-quinolone-dependent cell-to-cell communication. Microbiology 151 1113–1125 10.1099/mic.0.27631-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnoli K., Schwager S., Uehlinger S., Vergunst A., Viteri D. F., Nguyen D. T., et al. (2012). Exposing the third chromosome of Burkholderia cepacia complex strains as a virulence plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 83 362–378 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07937.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzini S., Udine C., Riccardi G. (2011a). Molecular approaches to pathogenesis study of Burkholderia cenocepacia, an important cystic fibrosis opportunistic bacterium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92 887–895 10.1007/s00253-011-3616-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzini S., Udine C., Sass A., Pasca M. R., Longo F., Emiliani G., et al. (2011b). Deciphering the role of RND efflux transporters in Burkholderia cenocepacia. PLoS ONE 6:e18902 10.1371/journal.pone.0018902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco N., Neshat S., Poole K. (1997). Conservation of the multidrug resistance efflux gene oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41 853–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot F. V., Lopez M. M., Poyot T., Neulat-Ripoll F., Lignon S., Caclard A., et al. (2013). Interplay between three RND efflux pumps in doxycycline-selected strains of Burkholderia thailandensis. PLoS ONE 8:e84068 10.1371/journal.pone.0084068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot F. V., Valade E., Garnotel E., Chevalier J., Villard C., Thibault F. M., et al. (2011). Involvement of the efflux pumps in chloramphenicol selected strains of Burkholderia thailandensis: proteomic and mechanistic evidence. PLoS ONE 6:e16892 10.1371/journal.pone.0016892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett P. J., Deshazer D., Woods D. E. (1998). Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48 317–320 10.1099/00207713-48-1-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. (2007). “Antibiotic resistance of Burkholderia spp.,” in Burkholderia Molecular Microbiology and Genomics, eds Coenye T., Vandamme P. (Norfolk: Horizon Bioscience; ), 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. L., Wadsworth C. D., Barry J. J., Goodall C. P. (1996). Nucleotide sequence analysis of a gene from Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia encoding an outer membrane lipoprotein involved in multiple antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40 307–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buroni S., Matthijs N., Spadaro F., Van Acker H., Scoffone V. C., Pasca M. R., et al. (2014). Differential roles of RND efflux pumps in antimicrobial drug resistance of sessile and planktonic Burkholderia cenocepacia cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 7424–7429 10.1128/AAC.03800-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buroni S., Pasca M. R., Flannagan R. S., Bazzini S., Milano A., Bertani I., et al. (2009). Assessment of three Resistance-Nodulation-Cell Division drug efflux transporters of Burkholderia cenocepacia in intrinsic antibiotic resistance. BMC Microbiol. 9:200 10.1186/1471-2180-9-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos C. G., Borst L., Cotter P. A. (2013). Characterization of BcaA, a putative classical autotransporter protein in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 81 1121–1128 10.1128/IAI.01453-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. Y., Bian H. S., Tan T. M., Mattmann M. E., Geske G. D., Igarashi J., et al. (2007a). Control of quorum sensing by a Burkholderia pseudomallei multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 189 4320–4324 10.1128/JB.00003-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. Y., Ong Y. M., Chua K. L. (2007b). Synergistic interaction between phenothiazines and antimicrobial agents against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 623–630 10.1128/AAC.01033-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. Y., Chua K. L. (2005). The Burkholderia pseudomallei BpeAB-OprB efflux pump: expression and impact on quorum sensing and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 187 4707–4719 10.1128/JB.187.14.4707-4719.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. Y., Chua K. L. (2010). Growth-related changes in intracellular spermidine and its effect on efflux pump expression and quorum sensing in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiology 156 1144–1154 10.1099/mic.0.032888-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. Y., Tan T. M. C., Ong Y. M., Chua K. L. (2004). BpeAB-OprB, a multidrug efflux pump in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 1128–1135 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1128-1135.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A. C., Dance D. A., Currie B. J. (2005). Bioterrorism, glanders and melioidosis. Euro. Surveill. 10 E1–E2; author reply E1–E2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenye T., Van Acker H., Peeters E., Sass A., Buroni S., Riccardi G., et al. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of chlorhexidine tolerance in Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 1912–1919 10.1128/AAC.01571-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. E., Beaupre A. J., Knudson S. E., Liu N., Yu W., Neckles C., et al. (2014). Substituted diphenyl ethers as a novel chemotherapeutic platform against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 1646–1651 10.1128/AAC.02296-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie B. J., Ward L., Cheng A. C. (2010). The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e900 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevinek P., Mahenthiralingam E. (2010). Burkholderia cenocepacia in cystic fibrosis: epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16 821–830 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubarry N., Du W., Lane D., Pasta F. (2010). Improved electrotransformation and decreased antibiotic resistance of the cystic fibrosis pathogen Burkholderia cenocepacia strain J2315. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 1095–1102 10.1128/AEM.02123-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K., Passador L., Srikumar R., Tsang E., Nezezon J., Poole K. (1998). Influence of the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux system on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 180 5443–5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlner-Gardiner C. C., Valvano M. A. (2002). Cloning and characterization of the Burkholderia vietnamiensis norM gene encoding a multi-drug efflux system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215 279–283 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki S., Ohnuma S., Horiuchi T., Takahashi I., Tsukui S., Nishimura Y., et al. (1996). Cloning of a gene from Escherichia coli that confers resistance to fosmidomycin as a consequence of amplification. Gene 175 83–87 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00128-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamberi T., Rocchiccioli S., Papaleo M., Magherini F., Citti L., Buroni S., et al. (2013). RND-4 efflux transporter gene deletion in Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315: a proteomic analysis. J. Proteome Sci. Comp. Biol. 2:1 10.7243/2050-2273-2-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glass M. B., Gee J. E., Steigerwalt A. G., Cavuoti D., Barton T., Hardy R. D., et al. (2006). Pneumonia and septicemia caused by Burkholderia thailandensis in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44 4601–4604 10.1128/JCM.01585-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golini G., Favari F., Marchetti F., Fontana R. (2004). Bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity of levofloxacin against clinical isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23 798–800 10.1007/s10096-004-1216-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove A. (2010). Urate-responsive MarR homologs from Burkholderia. Mol. Biosyst. 6 2133–2142 10.1039/c0mb00086h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglierame P., Pasca M. R., De Rossi E., Buroni S., Arrigo P., Manina G., et al. (2006). Efflux pump genes of the resistance-nodulation-division family in Burkholderia cenocepacia genome. BMC Microbiol. 6:66 10.1186/1471-2180-6-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad M. A., Skeldon A. M., Valvano M. A. (2010). Construction of aminoglycoside-sensitive Burkholderia cenocepacia strains for use in studies of intracellular bacteria with the gentamicin protection assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 3170–3176 10.1128/AEM.03024-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E. W. (1998). Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other non-fermentative bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27(Suppl. 1), S93–S99 10.1086/514909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S., Abe M., Kimoto M., Furukawa S., Nakazawa T. (2000). The DsbA-DsbB disulfide bond formation system of Burkholderia cepacia is involved in the production of protease and alkaline phosphatase, motility, metal resistance, and multi-drug resistance. Microbiol. Immunol. 44 41–50 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden H. S., Lim R., Brittnacher M. J., Sims E. H., Ramage E. R., Fong C., et al. (2012). Evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei in recurrent melioidosis. PLoS ONE 7:e36507 10.1371/journal.pone.0036507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley C. M., Luo J. X., Andreae C. A., Butler C. S., Soyer O. S., Titball R. W. (2014). Bacterial drug tolerance under clinical conditions is governed by anaerobic adaptation but not anaerobic respiration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 5775–5783 10.1128/AAC.02793-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakata Y., Kondo A., Hoshino K., Yano H., Arai K., Hirotani A., et al. (2009). Efflux pump inhibitors reduce the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34 343–346 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden M. T., Seth-Smith H. M., Crossman L. C., Sebaihia M., Bentley S. D., Cerdeno-Tarraga A. M., et al. (2009). The genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 an epidemic pathogen of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Bacteriol. 191 261–277 10.1128/JB.01230-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden M. T. G., Titball R. W., Peacock S. J., Cerdeno-Tarraga A. M., Atkins T. P., Crossman L. C., et al. (2004). Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 14240–14245 10.1073/pnas.0403302101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland D. J., Wesley A., Drinkovic D., Currie B. J. (2002). Cystic fibrosis and Burkholderia pseudomallei Infection: an emerging problem? Clin. Infect. Dis. 35 e138–e140 10.1086/344447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassem A. N., Forbes C. M., Speert D. P. (2014). Investigation of aminoglycoside resistance inducing conditions and a putative AmrAB-OprM efflux system in Burkholderia vietnamiensis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 13:2 10.1186/1476-0711-13-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassem A. N., Zlosnik J. E., Henry D. A., Hancock R. E., Ernst R. K., Speert D. P. (2011). In vitro susceptibility of Burkholderia vietnamiensis to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 2256–2264 10.1128/AAC.01434-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Carlson R., Tharpe W., Schell M. A. (1998). Characterization of genes involved in biosynthesis of a novel antibiotic from Burkholderia cepacia BC11 and their role in biological control of Rhizoctonia solani. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 3939–3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler T., Michea-Hamzehpour M., Henze U., Gotoh N., Curty L. K., Pechere J. C. (1997). Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 23 345–354 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler T., Van Delden C., Kocjanic Curty L., Hamzehpour M. M., Pechere J.-C. (2001). Overexpression of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux system affects cell-to cell signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183 5213–5222 10.1128/JB.183.18.5213-5222.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Chua K.-L., Schweizer H. P. (2006). Method for regulated expression of single-copy efflux pump genes in a surrogate Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain: identification of the BpeEF-OprC chloramphenicol and trimethoprim efflux pump of Burkholderia pseudomallei 1026b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 3460–3463 10.1128/AAC.00440-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Mayo M., Trunck L. A., Cheng A. C., Currie B. J., Schweizer H. P. (2008). Expression of resistance-nodulation-cell division efflux pumps in commonly used Burkholderia pseudomallei strains and clinical isolates from Northern Australia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102(Suppl. 1), S145–S151 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70032-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Z., Nikaido H., Poole K. (1995). Role of MexA-MexB-OprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39 1948–1953 10.1128/AAC.39.9.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Ibrahim M., Qiu H., Kausar S., Ilyas M., Cui Z., et al. (2015). Protein profiling analyses of the outer membrane of Burkholderia cenocepacia reveal a niche-specific proteome. Microb. Ecol. 69 75–83 10.1007/s00248-014-0460-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Cummings J. E., England K., Slayden R. A., Tonge P. J. (2011). Mechanism and inhibition of the FabI enoyl-ACP reductase from Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 564–573 10.1093/jac/dkq509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada L., Ronning C. M., Deshazer D., Woods D., Fedorova N., Kim H. S., et al. (2010). Continuing evolution of Burkholderia mallei through genome reduction and large-scale rearrangements. Genome Biol. Evol. 2 102–116 10.1093/gbe/evq003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutet S. A., Valvano M. A. (2011). Extreme antimicrobial peptide and polymyxin B resistance in the genus Burkholderia. Front. Microbiol. 2:159 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenthiralingam E., Urban T. A., Goldberg J. B. (2005). The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 144–156 10.1038/nrmicro1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravic A., Skocibusic M., Sprung M., Samanic I., Puizina J., Pavela-Vrancic M. (2012). Occurrence and antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Burkholderia cepacia complex in coastal marine environment. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 22 531–542 10.1080/09603123.2012.667797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J. E., Jr. (2006). Resistance in non-fermenting gram-negative bacteria: multidrug resistance to the maximum. Am. J. Infect. Control 34 S29–S37; discussion S64–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen A. S., Verbrugghen T., Declerck C., Ortmann R., Schlitzer M., Nelis H., et al. (2011). Resistance of the Burkholderia cepacia complex to fosmidomycin and fosmidomycin derivatives. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38 261–264 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T., Schweizer H. P. (2010). The BpeAB-OprB efflux pump of Burkholderia pseudomallei 1026b does not play a role in quorum sensing, virulence factor production, or extrusion of aminoglycosides but is a broad-spectrum drug efflux system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 3113–3120 10.1128/AAC.01803-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T., Schweizer H. P., Xu Z.-Q. (2011). In vitro activity of cethromycin against Burkholderia pseudomallei and investigation of mechanism of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 73–78 10.1093/jac/dkq391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine T., Morita Y., Kataoka A., Mizushima T., Tsuchiya T. (1999). Expression in Escherichia coli of a new multidrug efflux pump, MexXY, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43 415–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira N. P., Madeira A., Moreira A. S., Coutinho C. P., Sa-Correia I. (2011). Genomic expression analysis reveals strategies of Burkholderia cenocepacia to adapt to cystic fibrosis patients’ airways and antimicrobial therapy. PLoS ONE 6:e28831 10.1371/journal.pone.0028831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. A., Deshazer D., Reckseidler S., Weissman A., Woods D. E. (1999). Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y., Tomida J., Kawamura Y. (2012). MexXY multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 3:408 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair B. M., Cheung K. J., Jr., Griffith A., Burns J. L. (2004). Salicylate induces an antibiotic efflux pump in Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovar III (B. cenocepacia). J. Clin. Invest. 113 464–473 10.1172/JCI200419710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair B. M., Joachimiak L. A., Chattopadhyay S., Montano I., Burns J. L. (2005). Conservation of a novel protein associated with an antibiotic efflux operon in Burkholderia cenocepacia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245 337–344 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierman W. C., Deshazer D., Kim H. S., Tettelin H., Nelson K. E., Feldblyum T., et al. (2004). Structural flexibility in the Burkholderia mallei genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 14246–14251 10.1073/pnas.0403306101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., Pages J. M. (2012). Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36 340–363 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00290.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino K., Yamaguchi A. (2001). Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183 5803–5812 10.1128/JB.183.20.5803-5812.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Quinn A. L., Wiegand E. M., Jeddeloh J. A. (2001). Burkholderia pseudomallei kills the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans using an endotoxin-mediated paralysis. Cell Microbiol. 3 381–393 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. P., Van Delden C., Iglewski B. H. (1999). Active efflux and diffusion are involved in transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-to-cell signals. J. Bacteriol. 181 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters E., Nelis H. J., Coenye T. (2009). In vitro activity of ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, meropenem, minocycline, tobramycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole against planktonic and sessile Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64 801–809 10.1093/jac/dkp253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin E., Fondi M., Papaleo M. C., Maida I., Buroni S., Pasca M. R., et al. (2010). Exploring the HME and HAE1 efflux systems in the genus Burkholderia. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:164 10.1186/1471-2148-10-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podin Y., Sarovich D. S., Price E. P., Kaestli M., Mayo M., Hii K., et al. (2014). Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates from Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, are predominantly susceptible to aminoglycosides and macrolides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 162–166 10.1128/AAC.01842-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podnecky N. L., Wuthiekanun V., Peacock S. J., Schweizer H. P. (2013). The BpeEF-OprC efflux pump is responsible for widespread trimethoprim resistance in clinical and environmental Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 4381–4386 10.1128/AAC.00660-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2001). Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3 255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K., Krebes K., Mcnally C., Neshat S. (1993). Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J. Bacteriol. 175 7363–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. P., Sarovich D. S., Mayo M., Tuanyok A., Drees K. P., Kaestli M., et al. (2013). Within-host evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei over a twelve-year chronic carriage infection. MBio 4:4 10.1128/mBio.00388-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst K. L. (2011). The Analysis of Burkholderia pseudomallei Virulence and Efficacy of Potential Therapeutics. Ph.D. Dissertation, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Propst K. L., Mima T., Choi K. H., Dow S. W., Schweizer H. P. (2010). A Burkholderia pseudomallei ΔpurM mutant is avirulent in immune competent and immune deficient animals: candidate strain for exclusion from select agent lists. Infect. Immun. 78 3136–3143 10.1128/IAI.01313-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran R., Quinn R. F., Murray C., Mcculloch E., Williams C., Ramage G. (2010). Efflux pumps may play a role in tigecycline resistance in Burkholderia species. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36 151–154 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton L., Sass A., Baldwin A., Dowson C. G., Donoghue D., Mahenthiralingam E. (2013). Key role for efflux in the preservative susceptibility and adaptive resistance of Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 2972–2980 10.1128/AAC.00140-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass A., Marchbank A., Tullis E., Lipuma J. J., Mahenthiralingam E. (2011). Spontaneous and evolutionary changes in the antibiotic resistance of Burkholderia cenocepacia observed by global gene expression analysis. BMC Genomics 12:373 10.1186/1471-2164-12-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell M. A., Zhao P., Wells L. (2011). Outer membrane proteome of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei from diverse growth conditions. J. Proteome Res. 10 2417–2424 10.1021/pr1012398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulin T., Steinmetz I. (2001). Chronic melioidosis in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 1676–1677 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1676-1677.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. (2012a). “Mechanisms of Burkholderia pseudomallei antimicrobial resistance,” in Melioidosis - A Century of Observation and Research, ed. Ketheesan N. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. P. (2012b). Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei: implications for treatment of melioidosis. Future Microbiol. 7 1389–1399 10.2217/fmb.12.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. P. (2012c). When it comes to drug discovery not all Gram-negative bacterial biodefence pathogens are created equal: Burkholderia pseudomallei is different. Microb. Biotechnol. 5 581–583 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2012.00334.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoffone V. C., Spadaro F., Udine C., Makarov V., Fondi M., Fani R., et al. (2014). Mechanism of resistance to an antitubercular 2-thiopyridine derivative that is also active against Burkholderia cenocepacia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 2415–2417 10.1128/AAC.02438-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A. E., Laws T. R., D’elia R. V., Stokes M. G., Nandi T., Williamson E. D., et al. (2013). Protection against experimental melioidosis following immunization with live Burkholderia thailandensis expressing a manno-heptose capsule. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20 1041–1047 10.1128/CVI.00113-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim B. M., Chantratita N., Ooi W. F., Nandi T., Tewhey R., Wuthiekanun V., et al. (2010). Genomic acquisition of a capsular polysaccharide virulence cluster by non-pathogenic Burkholderia isolates. Genome Biol. 11:R89 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A. J., Newton P. N., Chierakul W., Chaowagul W., White N. J. (2003). Diabetes mellitus, insulin, and melioidosis in Thailand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36 e71–e72 10.1086/367861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. L., Mckay G. A., Poole K. (2003). Contribution of the MexXY multidrug transporter to aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 3202–3207 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3202-3207.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Hwang J., Yi H., Ulrich R. L., Yu Y., Nierman W. C., et al. (2010). The early stage of bacterial genome-reductive evolution in the host. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000922 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegos G. P., Haynes M. K., Schweizer H. P. (2012). Dissecting novel virulent determinants in the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Virulence 3 234–237 10.4161/viru.19844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng M., Hilgers M. T., Cunningham M. L., Borchardt A., Locke J. B., Abraham S., et al. (2013). Identification of bacteria-selective threonyl-tRNA synthetase substrate inhibitors by structure-based design. J. Med. Chem. 56 1748–1760 10.1021/jm301756m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z. X., Mac Aogain M., O’connor H. F., Fargier E., Mooij M. J., Adams C., et al. (2009). MexT modulates virulence determinants in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independent of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump. Microb. Pathog. 47 237–241 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trunck L. A., Propst K. L., Wuthiekanun V., Tuanyok A., Beckstrom-Sternberg S. M., Beckstrom-Sternberg J. S., et al. (2009). Molecular basis of rare aminoglycoside susceptibility and pathogenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei clinical isolates from Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e0000519 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng S. P., Tsai W. C., Liang C. Y., Lin Y. S., Huang J. W., Chang C. Y., et al. (2014). The contribution of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in clinical Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates: an emphasis on efflux pump activity. PLoS ONE 9:e104986 10.1371/journal.pone.0104986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Dawyndt P. (2011). Classification and identification of the Burkholderia cepacia complex: Past, present and future. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 34 87–95 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlaere E., Baldwin A., Gevers D., Henry D., De Brandt E., Lipuma J. J., et al. (2009). Taxon K, a complex within the Burkholderia cepacia complex, comprises at least two novel species, Burkholderia contaminans sp. nov. and Burkholderia lata sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59 102–111 10.1099/ijs.0.001123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktorov D. V., Zakharova I. B., Podshivalova M. V., Kalinkina E. V., Merinova O. A., Ageeva N. P., et al. (2008). High-level resistance to fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins in Burkholderia pseudomallei and closely related species. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102(Suppl. 1), S103–S110 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70025-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora S. K. (2002). Sherlock Holmes and a biological weapon. J. R. Soc. Med. 95 101–103 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock G. C., Estes D. M., Torres A. G. (2007). Glanders: off to the races with Burkholderia mallei. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277 115–122 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00949.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J., Birnie E., Weehuizen T. A., Alabi A. S., Huson M. A., In ’t Veld R. A., et al. (2015). Clinical, environmental, and serologic surveillance studies of melioidosis in Gabon, 2012-2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21 40–47 10.3201/eid2101.140762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J., Currie B. J., Peacock S. J. (2012). Melioidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 367 1035–1044 10.1056/NEJMra1204699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J., Van Der Poll T., White N. J., Day N. P., Peacock S. J. (2006). Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 272–282 10.1038/nrmicro1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield S. M., Rigg G. P., Kavari M., Webb A. K., Matthews R. C., Burnie J. P. (2002). Identification of an immunodominant drug efflux pump in Burkholderia cepacia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49 619–624 10.1093/jac/49.4.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsor G. L., Khaira B., Van Rossum T., Lo R., Whiteside M. D., Brinkman F. S. L. (2008). The Burkholderia genome database: facilitating flexible queries and comparative analyses. Bioinformatics 24 2803–2804 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li X. Z., Poole K. (2001). Fluoroquinolone susceptibilities of efflux-mediated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Burkholderia cepacia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48 549–552 10.1093/jac/48.4.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]