Abstract

Illegitimate tasks represent a task-level stressor derived from role and justice theories within the framework of “Stress-as–Offense-to-Self” (SOS; Semmer, Jacobshagen, Meier, & Elfering, 2007). Tasks are illegitimate if they violate norms about what an employee can properly be expected to do, because they are perceived as unnecessary or unreasonable; they imply a threat to one's professional identity. We report three studies testing associations between illegitimate tasks and well-being/strain. In two cross-sectional studies, illegitimate tasks predicted low self-esteem, feelings of resentment towards one's organization and burnout, controlling for role conflict, distributive injustice and social stressors in Study 1, and for distributive and procedural/interactional justice in Study 2. In Study 3, illegitimate tasks predicted two strain variables (feelings of resentment towards one's organization and irritability) over a period of two months, controlling for initial values of strain. Results confirm the unique contribution of illegitimate tasks to well-being and strain, beyond the effects of other predictors. Moreover, Study 3 demonstrated that illegitimate tasks predicted strain, rather than being predicted by it. We therefore conclude that illegitimate tasks represent an aspect of job design that deserves more attention, both in research and in decisions about task assignments.

Keywords: threat to self, well-being, strain, fairness, justice, role stress, self, job design

Stressors carry the potential to induce strain, increasing the risk for ill health and poor well-being. A prerequisite for strain to occur is that the attainment of important goals is threatened (Lazarus, 1999). Arguably, goals are especially important for most people if they are related to the self (Leary, 1999), that is to preserving a positive self-image. Based on the Stress-as-Offense-to-Self (SOS) theory (Semmer, Jacobshagen, Meier, & Elfering, 2007), the present paper addresses a specific task-related stressor that constitutes a threat to the self: the concept of illegitimate tasks. Tasks are perceived as illegitimate to the extent that employees think they cannot appropriately be expected from them. We contend that illegitimate tasks constitute stressors that are important for well-being beyond the effects of other occupational stressors.

Task-related stressors can threaten the self in several ways. First, they may impede performance. Examples are too high, unclear, or conflicting demands, or performance constraints (for an overview see Sonnentag & Frese, 2013). Because identity is tied to their work for many people (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, 2008), failing to reach performance standards may threaten the self, both in terms of self-evaluation as a competent individual (personal self-esteem) and in terms of evaluation by others (often called social esteem; Lazarus, 1999). Thus, by making good performance difficult, task-related stressors may threaten the self.

Tasks may be relevant for the self beyond reaching performance goals, however. Task design may carry social signals or messages (Pierce & Gardner, 2004). Thus, granting autonomy may be perceived as a message of trust in one's competence and dependability; having to work with inadequate tools may be seen as lack of care and appreciation (Semmer & Beehr, 2014). Intrinsic characteristics of tasks also may contain social messages – positive in terms of prestige (e.g. surgery) or negative in terms of stigma (“dirty” work; Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999).

We argue for yet another possibility: tasks may carry social messages that are not tied to their characteristics in terms of intrinsic aspects (e.g. dirty work), or in terms of task design (e.g. autonomy), but rather tied to role constellations. A task may be seen as perfectly normal in principle, yet contain a demeaning social message under specific circumstances. Specifically, tasks that do not conform to what can appropriately be expected from someone in terms of his or her role are perceived as illegitimate. Illegitimate tasks send an implicit message of disrespect that represents a potential threat to the self. Occupational stress research has largely neglected this task-related stressor, but we argue that illegitimate tasks constitute a stressor in their own right, which implies that they should explain variance in strain over and above other stressors.

The present article's goals are: (1) to describe the concept of illegitimate tasks and (2) to empirically substantiate their association with strain. As a new stressor concept can be justified only if it explains variance beyond established stressors, we conducted two (cross-sectional) studies showing associations of illegitimate tasks with well-being and strain (self-esteem, feelings of resentment and burnout), controlling for role conflict, social stressors and lack of distributive justice in Study 1, and for procedural and interactional justice in Study 2. In Study 3, we assessed the prediction of strain (irritability and resentment) by illegitimate tasks over two months, controlling for initial strain, and also tested reversed causation in terms of strain predicting illegitimate tasks. Demonstrating the importance of demeaning social messages that may be associated with tasks under specific circumstances adds an important, and hitherto widely neglected, stressor to occupational health psychology.

Illegitimate tasks

The core aspect of perceiving a task as illegitimate is that employees think they should not have to carry out this task (Semmer, McGrath, & Beehr, 2005; Semmer et al., 2007). They could make that judgement for several reasons. First, tasks can be seen as illegitimate if they are unreasonable. Specifically, tasks are unreasonable if they fall outside of the range of one's occupational role. Examples would be a nurse being asked to do work that is regarded as a service rather than a nursing activity (e.g. opening a window for patients who have recovered enough to do that by themselves; cf. Sabo, 1990), or a company driver being ordered to drive the superior's children to a sports event. Tasks may also be unreasonable if they are at odds with specific aspects of one's role, such as the level of experience, authority or expertise, as when a newly licensed chef is left alone with high-level customers. Second, tasks can be seen as illegitimate when they are considered unnecessary. Examples are organizational inefficiencies, as when data have to be re-entered because two computer systems are not compatible. Note that the lack of necessity may refer to any part of the chain leading to the task assignment, including early stages. Thus, one may acknowledge that re-entering data is unavoidable yet consider it an unnecessary task because the employer should have avoided buying two systems without ensuring their compatibility. The common feature of both unnecessary and unreasonable tasks is that the employee sees them as illegitimate; he or she should not be expected to perform them (“I shouldn't have to do this”; Björk, Bejerot, Jacobshagen, & Härenstam, 2013). It is this lack of legitimacy, and the social message of disrespect associated with it, that distinguishes illegitimate tasks from existing concepts in occupational stress research.

Tasks are not illegitimate because of intrinsic qualities, but because of their content for a given person, place, time or situation (Semmer et al., 2007). Thus, they do not have to be difficult to carry out (e.g. due to lack of resources) or to be aversive as such (e.g. “dirty work”) or because of circumstances (e.g. noise). Actually, the very same task may be considered legitimate or illegitimate depending on the context. For instance, nurses may consider opening a window perfectly legitimate if the patient is too frail to do it, because that would imply caring, which is at the core of the nursing role. The driver is unlikely to consider driving as such illegitimate; it is driving the superior's children that makes it illegitimate – and even that would be legitimate if the driver were the manager's private chauffeur. Having to do something that should be done by someone else (unreasonable task) or that is seen as a waste of time (unnecessary task) signals a lack of respect for the person who is expected to do it.

The issue of (il)legitimacy is related to the issue of peripheral (or secondary) versus core tasks. Being central to one's role, core tasks should typically be legitimate, but there are exceptions. Teachers may consider explaining things repeatedly to inattentive students illegitimate, although explaining things is a core task for them. Nor are peripheral tasks always seen as illegitimate, although they are more likely to be than core tasks (Semmer, Jacobshagen, & Meier, 2006). They may be considered legitimate as long as they support, rather than hamper, core activities (e.g. one may accept providing brief documentation but not extensive statistics).

The conceptual background: role theory and justice theory

The SOS theory (Semmer et al., 2007) focuses on the fact that people strive to maintain a positive self-image (Sedikides & Strube, 1997) and argues that a threat to one's self-image is at the core of many stressful experiences. One implication is that working conditions (including task characteristics) may contain social messages for an employee (Semmer & Beehr, 2014). The concept of illegitimate tasks grew from SOS theory because such tasks are postulated to send self-threatening messages. Role theory can explain what makes a task illegitimate; once appraised as illegitimate, such a task is perceived as unfair (or injust); justice theories therefore can best explain reactions once tasks are appraised as illegitimate.

Roles and identity

Organizational roles consist of behavioural expectations (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964) defining what may legitimately be expected from a role incumbent. Conversely, and important for the present study, roles also imply which behaviours cannot be expected, but this aspect of roles has not received much attention in the literature.

For many people, professional roles become part of their identity (Ashforth et al., 2008; Haslam & Ellemers, 2005) and, thus, part of the self (Oyserman, Elmore, & Smith, 2012). According to social identity theory, people tend to value their professional roles, they defend them against negative evaluations, and they make favourable social comparisons (Meyer, Becker, & van Dick, 2006). Affirming one's professional identity likely induces pride and self-esteem, whereas threats to that identity are stressful (Stets, 2005; Warr, 2007).

Contradictory expectations induce role conflict, a well-established stressor (Semmer et al., 2005). Illegitimate tasks represent a special case of role conflict; specifically, an instance of the (rarely studied) person-role conflict, defined as a conflict “between the focal person's internal standards or values and the defined role behavior” (Rizzo, House, & Lirtzman, 1970, p. 155). However, person-role conflict is described primarily in moral terms (Kahn et al., 1964); by constrast, illegitimate tasks relate to position-inappropriate role expectations, and thus contain specific elements that go beyond existing theory and research in the role stress domain.

Justice theory

Justice, or fairness, constitutes a broad domain of theorizing and research (Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel, & Rupp, 2001). Distributive justice is concerned with outcomes, and if one regards a task assignment as an outcome, illegitimate tasks represent distributive injustice. However, employees may also conclude that the decision about task distribution was made in an unfair way, and/or that it indicates disrespectful behaviour, in which case procedural and interactional (in)justice are relevant as well. Injustice constitutes a stressor (Greenberg, 2010). (In)justice often implies a message about one's social standing, thus affecting one's social esteem (Cropanzano et al., 2001) and one's “identity judgements” (Tyler & Blader, 2003). Thus, if employees feel treated unfairly, they are likely to feel disrespected, implying a threat to their sense-of-self. However, justice theories focus on the allocation of positions, resources and rewards (e.g. hiring, promotion or salary; Niehoff & Moorman, 1993), not on task assignments. Thus, justice theories can help explain reactions once tasks are appraised as illegitimate, but neither justice theories nor justice measures refer specifically to illegitimate tasks.

Illegitimate tasks as social stressors

Being assigned illegitimate tasks may be interpreted as a result of malevolence in the context of interpersonal tension, implying that a measure of social stressors would capture most of the variance associated with illegitimate tasks. However, the specific elements of illegitimate tasks are not part of theorizing about, or measurement of, social stressors (Dormann & Zapf, 2002). Furthermore, messages are rather direct in the case of social stressors, but only indirect in the case of illegitimate tasks. Thus, although illegitimate tasks may be regarded as a sign of social stressors, their specific characteristics render it a concept in its own right.

Illegitimate tasks and strain

As we regard illegitimate tasks as stressors, they should be associated with negative affective reactions, which, if experienced frequently, may create more enduring symptoms of strain, such as burnout, irritability and low self-esteem (Sonnentag & Frese, 2013).

General strain indicators

Stressors in general are related to a wide range of strains (Sonnentag & Frese, 2013); we therefore expect such associations for illegitimate tasks as well. In the present studies we examine two general strains: burnout and irritability. In the job demands-resources model (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001), illegitimate tasks would qualify as demands that should be associated with burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion and disengagement. Specifically, illegitimate tasks require mental and emotional effort, which should result in emotional exhaustion, and they undermine identification with one's work, which should result in disengagement. The affective reactions to illegitimate tasks should also induce irritability, a rather general work-related strain variable characterized by difficulties to control negative emotional reactions, and by a tendency to ruminate about work-related problems (Mohr, Müller, Rigotti, Aycan, & Tschan, 2006).

Strain indicators specifically pertinent for illegitimate tasks

Two strains are especially pertinent for illegitimate tasks. The first is feelings of resentment, such as anger, rancour or indignation (note that anger is a typical reaction to lack of fairness; Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). Second, as identity-threatening stressors (Thoits, 1991), illegitimate tasks constitute an offence to self, and thus should be related to low self-esteem.

Existing evidence and the current studies

Research on illegitimate tasks is still sparse, but the general notion that tasks that are not part of one's professional role are stressful has been hinted in the context of role stress (e.g. Rizzo et al., 1970). Motowidlo, Packard, and Manning (1986) included “non-nursing tasks” among stressful events for nurses. Gabriel, Diefendorff, and Erickson (2011) showed satisfaction with task accomplishment to be associated with affect more strongly for “direct care tasks” (i.e. tasks affirming the core role) than for “indirect care” tasks. Conversely, Peeters, Schaufeli, and Buunk (1995, p. 471) concluded from their findings that stressors that are inherently connected with one's profession are not perceived as very significant, suggesting that they may be seen as legitimate and therefore are not very stressful after all. However, the conceptual implications of such findings in terms of illegitimate tasks have not been fully elaborated in this research.

Only recently has empirical research directly addressed illegitimate tasks. In an interview study (Semmer et al., 2006), people perceived as illegitimate only 10% of tasks they categorized as “core” or primary to their professional self-definition, but almost 65% of secondary tasks (cf. Aiken et al., 2001; Gabriel et al., 2011, for a similar distinction between core and secondary tasks). Concerning correlates with strain, well-being and behaviour, illegitimate tasks have been shown to be related to lower job satisfaction and more feelings of resentment (Stocker, Jacobshagen, Semmer, & Annen, 2010) and to more counterproductive work behaviour (Semmer, Tschan, Meier, Facchin, & Jacobshagen, 2010). Kottwitz et al. (2013) demonstrated that participants had higher levels of cortisol, a frequently investigated stress indicator (Sonnentag & Frese, 2013), on measurement occasions when they had more illegitimate tasks and were vulnerable in terms of feeling less healthy than usual. Björk et al. (2013) reported associations of illegitimate tasks with feeling stressed and with job dissatisfaction in Sweden. In two diary studies in Switzerland and the USA, Eatough et al. (2014) showed that daily fluctuations in illegitimate tasks predicted fluctuations in state self-esteem. In addition, the US study also investigated, and found, effects on anger, depressed mood and state job satisfaction. Furthermore, in a diary study by Pereira, Semmer, and Elfering (2014) daily illegitimate tasks predicted reduced sleep quality.

Thus, there is preliminary support for illegitimate tasks as stressors. However, new stressor concepts require evidence that they do entail a worthwhile contribution. The few existing studies are promising, but further work is needed. The current studies aim at demonstrating the importance of illegitimate tasks; two are cross-sectional, controlling for different stressors, and one contains illegitimate tasks as a predictor of strain over time, controlling for initial strain.

STUDY 1

Study 1 investigated associations of illegitimate tasks with self-esteem, feelings of resentment and burnout cross-sectionally, controlling for role conflict, distributive injustice and social stressors, the importance of which was discussed above. Illegitimate tasks are expected to be associated negatively with self-esteem (Hypothesis 1) and positively with feelings of resentment (Hypothesis 2) and with burnout (Hypothesis 3).

Method study 1

Sample and procedure

In a graduate seminar at a Swiss university, two teaching assistants and 27 students recruited six to eight participants each among co-workers, family and friends, offering a link to a website, or a paper-and-pencil option. Participants had to hold their jobs for at least a year, and work at least 50% of a full-time equivalent (FTE). Of 220 people contacted, 190 (86%) responded; 15 used the electronic version and 175 sent questionnaires to the authors. Mean age was 37.9 years (SD = 10.95; range = 16–65); 102 participants (54%) were male; mean job tenure was 7.59 years (SD = 8.39), employment averaged 93% of an FTE (SD = 12.83). Occupations varied widely, but were mostly white-collar; only 14 participants (7.4%) were blue-collar. We did not ask for ethnicity.

Measures

The following variables were assessed.

Illegitimate tasks

The Bern Illegitimate Tasks Scale, BITS (Semmer et al., 2010) assesses unnecessary tasks with four items; they are introduced with the lead-in phrase “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which keep you wondering if …”, followed by statements such as “… they have to be done at all?” Four items on unreasonable tasks are introduced with the lead-in phrase “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which you believe …”, followed by statements such as “… should be done by someone else?” Responses ranged from never (1) to frequently (5).

As expected, an exploratory factor analysis yielded two factors representing the two facets (cf. Semmer et al., 2010), which were correlated at r = .56 (p < .01). Internal consistency was α = .75 for unreasonable tasks, α = .84 for unnecessary tasks and α = .85 for the total scale. After comparing several measurement models, we used illegitimate tasks as one construct, with the two facets as indicators (see sections on Data Analysis and on Measurement Models below).

Other stressors

Role conflict was assessed using two items from the uncertainty scale of the Instrument of Stress-related Task Analysis (ISTA; Semmer, Zapf, & Dunckel, 1995) as indicators. The items were “How often do you get contradictory instructions from different superiors?” (1 = very seldom/never to 5 = very often/continuously), and “From how many people do you regularly get instructions?” (1/2/3/4/5 = from none/one/two/three/ more than three superiors). The correlation between the two items was r = .46 (p < .01). Social stressors were assessed with five items from the social stressors scale by Frese and Zapf (1987), referring to tension and conflict with supervisors and colleagues (e.g. “with some colleagues there is often conflict”). The response format ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much); internal consistency was α = .77. Items were randomly assigned to three parcels containing 1, 2, and 2 items. Distributive injustice was measured with van Yperen's (1996) 6-item scale on inequitable relationships with one's organization. A sample item was “The rewards I receive are not proportional to my investments”. The response format ranged from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree); internal consistency was α = .91. Items were randomly assigned to three parcels containing two items each.

Well-being and strain

Self-esteem was measured using Rosenberg's (1965) 10-item scale. A sample item read “I take a positive attitude toward myself”. The response format ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); internal consistency was α = .82. Items were randomly assigned to three parcels of 3, 3, and 4 items, respectively. The feelings of resentment scale (Geurts, Buunk, & Schaufeli, 1994) asks to what extent one has feelings such as anger, indignation or disappointment towards one's organization. The response format ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). One item referring to unfairness was removed from this scale, because the measure of illegitimate tasks also contains an item involving unfair task assignments. Internal consistency for the resulting 6-item measure was α = .85. Items were randomly assigned to three parcels of two items each. The burnout scale (Demerouti et al., 2001) refers to the two core facets of emotional exhaustion and disengagement (or cynicism). We used four items for each facet, with answers ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The exhaustion scale contained items such as “During my work, I often feel emotionally drained”; internal consistency was α = .65. The disengagement scale contained items such as “It happens more and more often that I talk about my work in a derogatory way”; internal consistency was α = .78. As burnout “is conceived as a chronic stress syndrome whose main dimensions are exhaustion and cynicism” (Consiglio, Borgogni, Alessandri, & Schaufeli, 2013, p. 24), neither a reduction to one dimension (exhaustion) nor the use of each dimension (exhaustion and disengagement) separately would capture burnout as a construct in its own right. In line with Consiglio et al. (2013), who used burnout as one construct with scales as indicators, we therefore modelled burnout as a single construct with exhaustion and disengagement as indicators; they were correlated at r = .61; internal consistency for the burnout scale as a whole was α = 82.

Data analysis

Measurement models and structural models were estimated using Mplus, Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). We dealt with missing values by the full information maximum likelihood procedure (Schafer & Graham, 2002). To evaluate model fit, we present χ2 and df, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean residual (SRMR) of these, SRMR and CFI are the most appropriate for our sample size (Hu & Bentler, 1999). When comparing models, we also report the Akaike information criterion (AIC), which rewards parsimony.

Constructs were modelled using item parcelling, which is not without controversy, but has some distinct advantages; most notably increased reliability, more normal distributions and scale intervals that are smaller and more equal (Little, Cunningham, Sharar, & Widaman, 2002). Furthermore, if one wants to investigate associations between constructs rather than items or subconstructs, “then appropriate selection of scales or parceling of items can minimize or cancel out the effects of nuisance factors at a lower level of generality” (Little et al., 2002, p.171). We mostly assigned items randomly, however for constructs that are not unidimensional, we formed parcels by a strategy that has been called the internal consistency (Little et al., 2002) or “total aggregation” approach (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998). For instance, illegitimate tasks consist of two facets (unreasonable and unnecessary tasks). Two measurement models would correspond to this concept: (1) illegitimate tasks as a second-order construct, with the two facets as first-order constructs or (2) illegitimate tasks as a latent first-order construct, with the two facets as indicators (internal consistency approach). In both cases, the dimensionality of the construct is explicitly modelled rather than obscured by distributing items of the two subscales across parcels (Hall, Snell, & Foust, 1999; Little et al., 2002). These two measurement models were tested against a model using all eight items as indicators, and against a model with the two subscales as constructs.

We controlled for distributive injustice, role conflict and social stressors, because these are theoretically seen as competing stressors. Theoretically, we saw no reason why other control variables should be responsible for our findings. Therefore, there are good reasons not to include them in our models (Spector & Brannick, 2011). However, as many might wonder if other variables would affect our results, we reran our analysis controlling for age, sex, number of hours worked and tenure. We present these findings briefly; details can be obtained from the authors.

As hypotheses were directional, significance tests for path coefficients in the structural models were one-tailed (although associations between illegitimate tasks and well-being/strain would be significant with two-tailed tests as well).

Results study 1

Means, standard deviations, alphas and correlations are shown in Table 1 (upper part).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, correlations among variables and measurement models in Study 1.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Illegitimate tasks | 2.29 | 0.60 | .85 | ||||||||||

| 2. Role conflict | 2.04 | 0.84 | .37 | .46c | |||||||||

| 3. Social stressors | 1.65 | 0.66 | .48 | .38 | .77 | ||||||||

| 4. Distributive injustice | 2.69 | 1.21 | .49 | .25 | .52 | .91 | |||||||

| 5. Resentment | 2.61 | 1.10 | .52 | .27 | .52 | .56 | .85 | ||||||

| 6. Burnout | 1.85 | 0.50 | .57 | .37 | .47 | .47 | .55 | .82 | |||||

| 7. Self-esteem | 3.99 | 0.53 | −.35 | −.19 | −.36 | −.24 | −.31 | −.49 | .83 | ||||

| 8. Sexa | 0.46 | 0.50 | −.01 | −.02 | −.07 | −.03 | −.08 | .05 | −.09 | – | |||

| 9. Age | 37.91 | 10.95 | −.13 | −.18 | −.15 | −.09 | −.12 | −.12 | .09 | −.09 | – | ||

| 10. Hours workedb | 92.98 | 12.83 | .01 | .05 | .08 | −.06 | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.35 | −.13 | – | |

| 11. Job tenure | 7.95 | 8.39 | −.11 | −.09 | −.08 | −.06 | −.11 | −.05 | .09 | −.11 | .66 | .01 | – |

| Measurement models | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | ||||||

| Predictors model 1 (facets as parcels) | 85.81 | 29 | .935 | .898 | .102 | .050 | 4375.12 | ||||||

| Predictors model 2 (2nd order) | 253.48 | 96 | .888 | .860 | .093 | .075 | 7009.05 | ||||||

| Predictors model 3 (two variables) | 248.14 | 94 | .890 | .860 | .093 | .074 | 7007.70 | ||||||

| Predictors model 4 (one variable) | 298.70 | 98 | .857 | .825 | .104 | .075 | 7050.26 | ||||||

| Dependent variables model | 17.96 | 17 | .999 | .998 | .017 | .032 | 2927.57 | ||||||

Note: Pearson correlations; Cronbach's α's are presented in the diagonal (given in italics). N = 190; r ≥ │.15│ p ≤ .05; r ≥ │.19│ = p ≤ .01 (two-tailed).

Predictor models contain all stressors (illegitimate tasks, role conflict, social stressors and distributive injustice); Model 1 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the two subscales as indicators; Model 2 = illegitimate tasks as second-order construct, with unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as first-order constructs; Model 3 = unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as two separate constructs (r unn−unr = .69, p ≤ .01); Model 4 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the eight items as indicators; the dependent variables model contains feelings of resentment, burnout and self-esteem.

0 = f; 1 = m; bin percent of a full time equivalent (FTE); ccorrelation between the two items.

Measurement models

The fit of measurement models for stressors and strain is shown in the lower part of Table 1. For the predictors, we compared four measurement models containing all stressors [role conflict, social stressors, distributive injustice and illegitimate tasks (i.e. BITS)], but differing with regard to BITS. Model 1, with BITS as one construct with the two subscales as indicators, corresponds most closely to our theoretical premises, and emerged as the best model for all but one of the indices (RMSEA); note that the indices recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) for our sample size (CFI and SRMR) and the Akaike index were best for this model. We therefore proceeded with Model 1 in our analyses. For well-being/strain (self-esteem, feelings of resentment and burnout), the measurement model yielded an excellent fit.

Structural model

The structural model, shown in Figure 1, fits the data well. Confirming Hypotheses 1–3, illegitimate tasks predicted self-esteem, resentment and burnout, explaining 9%, 6% and 12% variance, respectively, over and above the other stressors.

Figure 1. Structural model Study 1: Predicting well-being/strain by illegitimate tasks, role conflict, social stressors, and distributive injustice. N = 190. Path coefficients in bold are significant at *p ≤ .05 or **p ≤ .01 (one-tailed). χ2 = 237.10; df = 114; CFI = .930; TLI = .906; RMSEA = .075; SRMR = .049.

When we reran our model including controls for age, sex, number of hours worked and tenure, results stayed essentially the same. Importantly, paths from illegitimate tasks to the three well-being/strain variables changed by .02 at the most, and all remained statistically significant.

Following the advice of an anonymous reviewer, we tested for mediation, so that illegitimate tasks would predict higher distribute injustice, which, in turn, would predict lower well-being/more strain. No such mediation turned out to be significant. Details of these analyses can be obtained from the first author.

Discussion study 1

Study 1 confirmed that illegitimate tasks were related to well-being and strain, over and above role conflict, distributive injustice and social stressors, which were chosen because of their conceptual overlap with illegitimate tasks. In line with hypotheses, these results suggest that illegitimate tasks are, indeed, a stressor in its own right. However, although illegitimate tasks can be regarded as a special case of distributive injustice (note the substantial correlation between these constructs), people may well appraise them in terms of procedural and interactional (in)justice as well. In our second study, we therefore examined if illegitimate tasks predicted strain over and above procedural and interactional as well as distributive justice. Concerning the mediation results, see the General Discussion.

STUDY 2

Study 2 tested the same hypotheses as Study 1, postulating that illegitimate tasks are negatively associated with self-esteem (H1), and positively with feelings of resentment (H2) and burnout (H3), however, with a new sample and controlling for distributive, procedural and interactional justice (called justice, rather than injustice, because all items are positively worded).

Method study 2

Sample and procedure

Questionnaires were distributed by internal mail in a Swiss Government department and sent back directly to the University. Of 677 questionnaires distributed, 224 (33%) were returned. Mean age was 41.8 years (SD = 11.5; range = 17–64); 126 participants (56%) were male; mean job tenure was 6.0 years (SD = 6.3); employment averaged 91.5% of an FTE (SD = 16.18). The sample contained a wide range of white-collar occupations, and no blue-collar occupations. We did not ask for ethnicity.

Measures

We assessed illegitimate tasks, three dimensions of organizational justice and the same indicators of well-being/strain as in Study 1.

Work characteristics

Illegitimate tasks were again assessed with the BITS (Semmer et al., 2010). Internal consistency was α = .85 for unreasonable tasks, α = .88 for unnecessary tasks and α = .88 for the total scale; the facets were correlated at r = .51. Organizational justice was assessed in terms of distributive, procedural and interactional justice, using an adapted version of the scales by Niehoff and Moorman (1993). For distributive justice, participants indicated the fairness of outcomes such as pay and workload on a 5-item scale (e.g. “For the amount of work you do, how fair are your pay and benefits?”). Responses ranged from 1 (very unfair) to 5 (very fair); internal consistency was α = .83. For procedural justice, participants evaluated six statements reflecting Leventhal's (1980) criteria (e.g. consistency, bias). A sample item was “Job decisions are made by my supervisor in an unbiased manner”. Responses ranged from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree); internal consistency was α = .83. The nine items of the interactional justice scale described ways in which supervisors treat subordinates (see Bies & Moag, 1986). A sample item was “When decisions are made about my job, my supervisor treats me with respect and dignity”. Responses ranged from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree); internal consistency was α =.97. Correlating highly, procedural and interactional justice are often combined (e.g. Fox, Spector, & Miles, 2001); their correlation in our study was r = .87, and combining them yielded an internal consistency of α =.97; we therefore modelled them as one construct, with procedural and interactional justice as parcels.

Well-being and strain

As in Study 1, self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg's (1965) 10-item scale; α = .85; feelings of resentment with the scale by Geurts et al. (1994); α = .85, and burnout with the measure by Demerouti et al. (2001). For burnout, internal consistency was α = .76 for exhaustion, α = .85 for disengagement and α = .86 for the total scale.

Results study 2

Means, standard deviations, alphas and correlations are shown in Table 2 (upper part).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, correlations among variables and measurement models in Study 2.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Illegitimate tasks | 2.49 | 0.71 | .88 | |||||||||

| 2. Distributive justice | 3.49 | 0.76 | −.34 | .82 | ||||||||

| 3. Interactional and procedural justice | 4.87 | 1.26 | −.61 | .34 | .97 | |||||||

| 4. Resentment | 2.97 | 1.51 | .66 | −.31 | −.56 | .93 | ||||||

| 5. Burnout | 2.09 | 0.60 | .62 | −.34 | −.53 | .71 | .86 | |||||

| 6. Self-esteem | 4.12 | 0.54 | −.26 | −.07 | .05 | −.30 | −.34 | .85 | ||||

| 7. Sexa | 0.56 | 0.50 | .03 | .09 | .02 | −.02 | −.05 | .05 | – | |||

| 8. Age | 41.75 | 11.51 | −.02 | .09 | −.14 | .09 | −.09 | .05 | .19 | – | ||

| 9. Hours workedb | 91.49 | 16.18 | .02 | −.10 | .01 | −.01 | −.04 | .07 | .34 | .03 | – | |

| 10. Job tenure | 5.99 | 6.34 | −.01 | .11 | −.10 | .07 | .04 | −.04 | .23 | .56 | .03 | – |

| Measurement models | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | |||||

| Predictors model 1 (facets as parcels) | 4.87 | 6 | 1 | 1 | .000 | .016 | 3046.00 | |||||

| Predictors model 2 (2nd order) | 107.25 | 49 | .962 | .949 | .073 | .050 | 6007.68 | |||||

| Predictors model 3 (two variables) | 106.94 | 48 | .962 | .948 | .074 | .050 | 6079.36 | |||||

| Predictors model 4 (one variable) | 357.30 | 51 | .802 | .744 | .164 | .089 | 6323.72 | |||||

| Dependent variables model | 19.16 | 17 | .998 | .997 | .024 | .025 | 3486.38 | |||||

Note: Pearson correlations; Cronbach's α's are presented in the diagonal (given in italics). N = 224; r ≥ │.14│ p ≤ .05; r ≥ │.19│ = p ≤ .01 (two-tailed).

Predictor models contain all work characteristics (illegitimate tasks, distributive justice, and interactional & procedural justice); Model 1 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the two subscales as indicators; Model 2 = illegitimate tasks as second-order construct, with unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as first-order constructs; Model 3 = unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as two separate constructs (r unn−unr = .55, p ≤ .01); Model 4 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the eight items as indicators; the dependent variables model contains feelings of resentment, burnout and self-esteem.

0 = f; 1 = m; bin percent of a full time equivalent (FTE).

Measurement models

The fit of the measurement models is shown in the lower part of Table 2. For the predictors, we again compared four models that differed with regard to illegitimate tasks. Model 1, with BITS as a single construct with the two subscales as indicators, clearly emerged as the best model. For well-being/strain, the fit was excellent.

Structural model

The structural model (Figure 2) fits the data well. Confirming Hypotheses 1–3, illegitimate tasks predicted self-esteem, resentment and burnout, explaining 18%, 31% and 34% of the variance, respectively, over and above the other stressors.

Figure 2. Structural model Study 2: Predicting well-being/strain by illegitimate tasks and different forms of justice. N = 200. Path coefficients in bold are significant at *p ≤ .05 or **p ≤ .01 (one-tailed). χ2 = 86.79; df = 62; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .042; SRMR = .036.

When we reran our model including controls for age, sex, number of hours worked and tenure, results stayed essentially the same. Importantly, paths from illegitimate tasks to the well-being/strain variables changed between .02 and .07, and all remained statistically significant.

As in Study 1, we tested for mediation, so that illegitimate tasks would predict low justice, which, in turn, would predict better well-being/lower strain. No such mediation was significant. Details on these analyses can be obtained from the first author.

Discussion study 2

In Study 2 illegitimate tasks explained unique variance in all three outcomes, over and above distributive and procedural/interactional justice. Our reasoning that illegitimate tasks can be regarded as a special type of injustice is supported by their substantial correlation with the justice variables; it is particularly strong with procedural/interactional justice, suggesting that task illegitimacy may stem from the way employees feel treated at least as much as from the actual outcome. Showing that illegitimate tasks were related to strain while controlling multiple justice variables in an independent sample is the main contribution of Study 2. However, Study 2 again was cross-sectional. Although studies with multiple time periods do not establish causality, they can make a stronger case for a causal interpretation, and Study 3 took this approach. Details of these analyses can be obtained from the first author.

STUDY 3

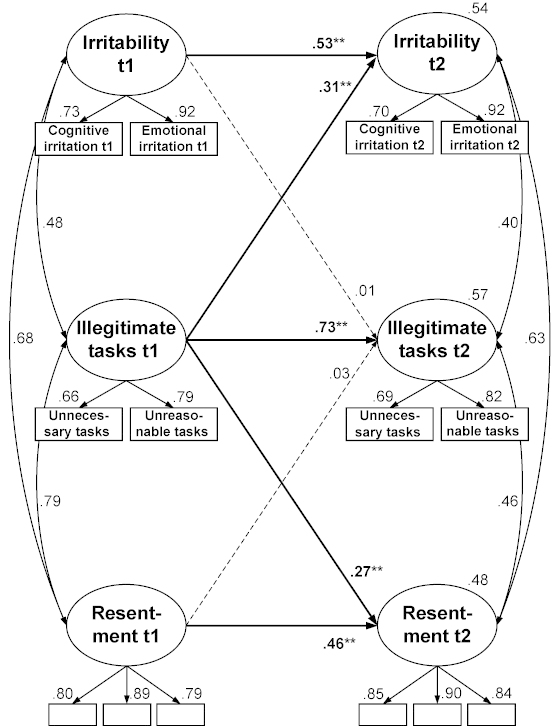

As associations between illegitimate tasks and strain may be due to strain leading to illegitimate tasks, Study 3 is a preliminary investigation testing the hypotheses that illegitimate tasks predict higher values in two strain indicators, which are irritability (Hypothesis 1) and resentment (Hypothesis 2) over time, controlling for the baseline values of strain.

Method study 3

Sample and procedure

In a graduate seminar in psychology in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, each of 17 graduate students recruited 25 participants among family, friends and co-workers. Questionnaires were provided online; participants created a unique personalized code, allowing us to connect the questionnaires for each person while guaranteeing anonymity.

Time lags in research should correspond to the time during which strain indicators develop (Taris & Kompier, 2014). Unfortunately, there is no firm knowledge about time frames for the development of strain indicators, and therefore no strong basis for decisions about optimal time lags (Dormann & van de Ven, 2014). Time lags of one year and more are seen as adequate by many (Taris & Kompier, 2014), but there also is evidence that changes in strain indicators may occur much more quickly (Sonnentag & Frese, 2013). Our decision for a lag of two months was driven by evidence that months, rather than years, are likely to represent an optimal time lag (Dormann & van de Ven, 2014), and by the pragmatic consideration that people might resent having to fill in the same questionnaire twice within a shorter interval (e.g. one month).

Of 424 participants initially recruited, 395 (93%) answered the questionnaire at time 1 (t1), and 290 (68% of the initial sample, 73% of t1 participants) also responded at time 2 (t2). Mean age was 40 years (SD = 10.44, range = 21–61); the majority was male (237 = 81.7%), mean job tenure was 14.1 years (SD = 10.51), percentage of employment averaged 96.0% of an FTE (SD = 11.89). The sample contained a wide range of occupations, but almost all (98%) were white-collar, and most (80%) were government employees. We did not ask for ethnicity.

Measures

Illegitimate tasks and two strains were measured over time.

Stressors

As in Studies 1 and 2, the BITS (Semmer et al., 2010) was used to assess illegitimate tasks; the two facets had internal consistencies of α = .81/.82 (unreasonable tasks) and α = .82/.83 (unnecessary tasks) at t1 and t2, respectively; they were correlated at r = .54 (t1) and .57 (t2); internal consistency for the total scale was α = .86 and .86 at t1/t2.

Strain

Two measures of strain were employed. Feelings of resentment were assessed with the resentment scale by Geurts et al. (1994), as in Studies 1 and 2; internal consistency was α = .86/.89 at t1/t2. Irritability was assessed with the 8-item irritation scale (Mohr et al., 2006), which contains two facets: “Cognitive irritation” refers to a tendency to ruminate about work (e.g. “It is hard for me to switch off my mind after work”); internal consistency was α = .79/.82 at t1/t2. “Emotional irritation” refers to an inability to control one's affective reactions (e.g. “I get irritated easily, although I don't want this to happen”); internal consistency was α = .91/.92 at t1/t2. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much).The two facets correlated at r = .66 at t1, and r = .63 at t2; internal consistency for the total scale was α = .91 at both times.

Results study 3

Means, standard deviations, alphas and correlations are shown in Table 3 (upper part).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics, correlations among variables and measurement models in Study 3.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Illegitimate tasks T1 | 2.52 | 0.70 | .85 | |||||||||

| 2. Illegitimate tasks T2 | 2.63 | 0.71 | .66 | .87 | ||||||||

| 3. Resentment T1 | 2.85 | 1.09 | .60 | .49 | .85 | |||||||

| 4. Resentment T2 | 3.04 | 1.22 | .49 | .57 | .64 | .89 | ||||||

| 5. Irritability T1 | 3.07 | 1.21 | .37 | .33 | .56 | .42 | .91 | |||||

| 6. Irritability T2 | 3.14 | 1.19 | .40 | .47 | .53 | .66 | .68 | .91 | ||||

| 7. Sexa | 1.18 | 0.39 | −.20 | −.25 | −.22 | −.23 | −.10 | −.12 | – | |||

| 8. Age | 39.99 | 10.44 | −.07 | −.18 | −.04 | −.15 | −.08 | −.13 | −.07 | – | ||

| 9. Hours workedb | 95.97 | 11.89 | .15 | .14 | .10 | .17 | .09 | .12 | −.44 | −.14 | – | |

| 10. Job tenure | 14.10 | 10.51 | .00 | −.06 | .06 | −.07 | .01 | −.07 | −.25 | .83 | .07 | – |

| Measurement models | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | |||||

| Model 1 (facets as parcels) | 95.77 | 59 | .987 | .979 | .046 | .036 | 9811.40 | |||||

| Model 2 (2nd order) | 428.44 | 274 | .966 | .960 | .044 | .053 | 18,403.86 | |||||

| Model 3 (two variables) | 408.56 | 267 | .969 | .962 | .043 | .051 | 18,397.98 | |||||

| Model 4 (one variable) | 704.70 | 281 | .906 | .892 | .072 | .062 | 18,666.12 | |||||

Note: Pearson correlations; Cronbach's α's are presented in the diagonal (given in italics). N = 283; r≥ ≥ │.12│ p ≤ .05; r ≥ │.17│ p ≤ .01 (two-tailed).

All measurement models contain all variables at both measurement time points (illegitimate tasks, feelings of resentment, and irritability); Model 1 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the two subscales as indicators; Model 2 = illegitimate tasks as second-order construct, with unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as first-order constructs; Model 3 = unnecessary and unreasonable tasks as two separate constructs (r unnT1−unrT1 = .62, p ≤ .01; r unnT2−unrT2 = .63, p ≤ .01); Model 4 = illegitimate tasks as single construct with the eight items as indicators.

0 = f; 1 = m; bin percent of a full time equivalent (FTE).

Measurement models

Of four measurement models, the one containing BITS as a single construct with the two subscales as indicators (Table 3, lower part) again emerged as the best model for all but one of the indices (RMSEA); it was used in our analyses.

Structural model

In a well-fitting model (Figure 3), illegitimate tasks at t1 predicted both strains at t2, with initial strain values controlled. Paths from strain t1 to illegitimate tasks t2 were not significant, yielding no evidence for reversed causation. Both hypotheses are confirmed.

Figure 3. Structural model Study 3: Predicting strain by illegitimate tasks longitudinally. N = 290. Path coefficients in bold are significant at *p ≤ .05 or **p ≤ .01 (one-tailed). χ2 = 103.01; df = 61; CFI = .985; TLI = .977; RMSEA = .049; SRMR = .036.

When we reran our model including age, sex, number of hours worked and tenure, results stayed essentially the same. Importantly, paths from illegitimate tasks to the strain variables changed between .01 and .03, and both remained statistically significant. Details on these analyses can be obtained from the first author.

Discussion study 3

Study 3 overcomes a basic weakness of Studies 1 and 2, which were cross-sectional. Although not proving causality, results of Study 3 make an explanation of the associations in terms of strain causing illegitimate tasks unlikely. However, the influence of third variables cannot be ruled out, and the lack of control variables constitutes a serious weakness of Study 3.

General discussion

Illegitimate tasks as stressors

Illegitimate tasks are postulated to violate norms about which tasks can legitimately be expected from a job incumbent. In Studies 1 and 2, we found such tasks to predict well-being/strain, over and above other stressors with similar theoretical roots (role conflict, injustice) or representing the same general category (social stressors). In Study 3, illegitimate tasks predicted strain (irritability and resentment) two months later. Taken together, the present studies strongly support the proposition that illegitimate tasks are an important task-level stressor that merits further study.

We argued that illegitimate tasks affect one's professional identity, and thus, the self, because role expectancies are violated. Our results cannot confirm every aspect of the proposed mechanisms, but they are in line with our reasoning. Confirming some overlap, role conflict, (in)justice and social stressors correlated with illegitimate tasks; but they cannot explain the effects of illegitimate tasks, suggesting that associations with strain are quite specific. Like role conflict in general, illegitimate tasks are a hindrance stressor; which – in contrast to challenge stressors – does not contain challenging aspects that can boost the self (Widmer, Keller, Gardner, & Semmer, 2014; Widmer, Semmer, Kälin, Jacobshagen, & Meier, 2012).

As one would expect if illegitimate tasks are stressors, they were related to a broad range of indicators of well-being/strain; their associations with feelings of resentment and self-esteem are theoretically especially pertinent, however – resentment because it represents reactions that are typical for appraisals of unfairness (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001) and self-esteem because illegitimate tasks are proposed to threaten the self (Semmer et al., 2007).

We focused on illegitimate tasks rather than its two subconstructs, as these share the same conceptual core. Focusing on the subconstructs would be supported empirically if measurement models containing the two subscales as separate constructs had shown a better fit than our model, or if the subscales were differentially associated with other constructs. Both conditions did not apply (analyses not reported here; details can be obtained from the first author). However, focusing on a superordinate construct and on its subconstructs both constitute viable approaches (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998), and further research may well reveal specific features of the subconstructs that are worth being studied in their own right. Of the two facets, unreasonable tasks, which concern the specific role of a particular employee, consistently showed stronger associations with outcomes than unnecessary tasks, which refer to the employee role in general.

As we had argued that illegitimate tasks should elicit feelings of being treated in an unfair way, a reviewer suggested that we test (in-)justice as a mediator between illegitimate tasks and well-being/strain. No such effects were found. We see two explanations for these results. First, our argument that illegitimate tasks are a special case of injustice may be wrong. Given the substantial association between illegitimate tasks and all forms of (in-)justice, this conclusion seems unlikely. Furthermore, in all mediation analyses, illegitimate tasks predicted (in-)justice; mediation was not obtained because injustice did not predict lower well-being/more strain in Study 1, and the justice variables did not predict better well-being/less strain in Study 2; rather, the direct effects of illegitimate tasks remained strong and statistically significant. It seems more likely that illegitimate task contain very specific elements of injustice related to task assignment, which are not covered by the traditional measures of (in-)justice but are so important as to overshadow the effects of the traditional (in-)justice measures in many cases. This argument is, however, speculative, and further research will be necessary to deal with this issue.

Limitations and strengths

Our reliance on self-report implies the danger of common method variance. However, we controlled for other variables measured by self-report, thus also controlling for the method variance shared; yet, illegitimate tasks remained a predictor. In Study 3 we controlled for the strain variables at baseline and still found the predicted relationships. Thus, the common method problem seems unlikely to have seriously distorted our results. Nevertheless, it would be important to use additional sources of information, such as supervisors and colleagues.

Whereas Studies 1 and 2 are cross-sectional, precluding conclusions about the direction of effects, illegitimate tasks predicted strain over two months in Study 3, rendering strain as a predictor of illegitimate tasks an unlikely explanation. However, Study 3 cannot rule out effects of third variables, and the fact that no other stressors were controlled certainly is a limitation of Study 3. Furthermore, its time lag was very short; studies with longer time frames are necessary.

Another issue is generalizability. Single studies often have narrowly drawn samples, and our studies are susceptible to that problem; furthermore, all three samples are Swiss. However, three independent samples yielded results conforming to hypotheses, arguing against an explanation in terms of selection bias; furthermore, two recent studies confirmed associations between illegitimate tasks and strain in Sweden (Björk et al., 2013) and the USA (Eatough et al., 2014). Nevertheless, more research with different samples in various countries is needed.

Implications for research

Future research, including diary studies and experiments, should test whether feeling offended can be confirmed as an immediate reaction to illegitimate tasks. Also, specific emotional reactions should be investigated. For instance, if a perceived offence is transformed into a negative self-evaluation, resulting in lower self-esteem, guilt or shame may result (Dickerson, Gruenewald, & Kemeny, 2004), possibly in combination with anger (“humiliated fury”; Tangney, Wagner, Hill-Barlow, Marschall, & Gramzow, 1996). Some of these emotions may mediate the stressor–strain relationship, which should be tested in future research.

We controlled for role conflict, forms of (in)justice and social stressors in Studies 1 and 2. However, other constructs, such as psychological contracts (Morrison & Robinson, 1997) could be related to illegitimate tasks and affect outcomes. Unlike illegitimate tasks, the psychological contract is based on promises, but not necessarily related to tasks. Like illegitimate tasks, however, the psychological contract refers to expectations, and violations are perceived as unfair and tend to induce similar reactions as illegitimate tasks (e.g. resentment and anger; Morrison & Robinson, 1997). In addition, further studies should investigate more possible outcomes, such as engagement or turnover, and biological measures such as catecholamines or skin conductance.

A further avenue concerns individual differences. Kottwitz et al. (2013) show that personal resources, such as (perceived) health, can buffer the effects of illegitimate tasks. Conversely, people high in neuroticism or low in agreeableness (who tend to distrust others' intentions; Semmer & Meier, 2009) might react more strongly to illegitimate tasks and strain. Also, there might be especially pertinent moderators, such as justice sensitivity (Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes, & Arbach, 2005), or identification with one's jobs, profession or organization. Furthermore, some people may react to illegitimate tasks more with anger, others more with shame and lower self-esteem. Finally, role definitions differ, so some may see tasks as part of their role that others would not (Morrison, 1994); also, supervisors may tend to have a broader concept of legitimate demands, as they are responsible for the functioning of larger units.

As cultures are characterized by shared beliefs (Haslam & Ellemers, 2005; Moreland & Levine, 2001), a task considered illegitimate in one culture may be considered legitimate in others; this may also apply to professional cultures (cf. the term “non-nursing activities”; Sabo, 1990). Furthermore, what is considered illegitimate may change over time.

Practical implications

Supervisors should pay special attention to social messages they communicate by assigning certain tasks to employees (Semmer & Beehr, 2014). Potential threats to professional identities may be obvious when tasks are clearly demeaning, but less so for more subtly illegitimate tasks. The important conclusion therefore is that supervisors should be aware of the characteristics of illegitimate tasks and try to avoid assigning them wherever possible. However, it seems unlikely that illegitimate tasks can be avoided totally. Assigning potentially illegitimate tasks may be justified by circumstances (e.g. illness of those normally dealing with them). In such cases, explicit justifications may help to avoid offence, as research on interactional justice suggests (Cropanzano et al., 2001); also, such justifications might activate an aspect of an employee's identity that is congruent with performing the task (e.g. the “good soldier”), thus rendering it more meaningful (Oyserman et al., 2012). If one needs to assign tasks that exist only due to earlier mistakes (e.g. suggestions for optimizing task organization were ignored), it might be a good idea to apologize. It could also help if supervisors themselves participate in carrying out such tasks, demonstrating that they do not expect things from others that they are unwilling to do themselves. Whatever they decide, they should be aware of potential threats to professional identity, thus making informed choices based on weighing pros and cons, rather than simply communicating assignments without considering the potential offence. At this point, we cannot ascertain to which degree appraisals of tasks as illegitimate are likely to converge between supervisors and employees, but such considerations certainly are worth being included in training.

Conclusion

Illegitimate tasks constitute a stressor that is worthy of further investigation. Beyond their specific characteristics, illegitimate tasks point to the necessity of considering the social meaning of job design, notably with regard to offense to the self (Semmer & Beehr, 2014; Semmer et al., 2007). Carrying out core activities that are tied to one's professional identity is likely to reinforce a positive self-image, whereas activities that run counter to one's professional identity are likely to be perceived as offending the self, and therefore to be stressful.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to a number of people for their support in conducting this research and writing this paper. We thank Anita C. Keller for help with the Mplus program. Robert D. Pritchard, William D. Crano and Richard L. Moreland made helpful comments at various stages of this manuscript. Above all, however, this research has profited from discussions with the late Joe McGrath. These discussions were inspiring, profound, and fun. We therefore would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Joseph E. McGrath.

Funding Statement

Part of this research was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

- Aiken L. H., Clarke S. P., Sloane D. M., Sochalski J. A., Busse R., Clarke H., et al. Shamian J. Nurses' reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001:43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B. E., Harrison S. H., Corley K. G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management. 2008:325–374. doi: 10.1177/0149206308316059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B. E., Kreiner G. E. “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Academy of Management Review. 1999:413–434. doi: 10.1177/0149206308316059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R. P., Edwards J. R. A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 1998:45–87. doi: 10.1177/109442819800100104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bies R. J., Moag J. S. Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In: Lewicki R. J., Sheppard B. H., Bazerman M. H., editors. Research on negotiation in organizations. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1986. pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Björk L., Bejerot E., Jacobshagen N., Härenstam A. I shouldn't have to do this: Illegitimate tasks as a stressor in relation to organizational control and resource deficits. Work & Stress. 2013:262–277. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2013.818291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Charash Y., Spector P. E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2001:278–321. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2001.2958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio C., Borgogni L., Alessandri G., Schaufeli W. B. Does self-efficacy matter for burnout and sickness absenteeism? The mediating role of demands and resources at the individual and team levels. Work & Stress. 2013:22–42. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2013.769325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Byrne Z. S., Bobocel D. R., Rupp D. E. Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001:164–209. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Bakker A. B., Nachreiner F., Schaufeli W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001:499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson S. S., Gruenewald T. L., Kemeny M. E. When the social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality. 2004:1191–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormann C., van de Ven B. Timing in methods for studying psychosocial factors at work. In: Dollard M., Shimazu A., Nordin R. B., Brough P., Tuckey M., editors. Psychosocial factors at work in the Asia Pacific. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann C., Zapf D. Social stressors at work, irritation, and depressive symptoms: Accounting for unmeasured third variables in a multi-wave study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2002:33–58. doi: 10.1348/096317902167630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eatough E. M., Meier L. L., Igic I., Elfering A., Spector P. E., Semmer N. K. Manuscript submitted for publication; 2014. You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well-being. [Google Scholar]

- Fox S., Spector P. E., Miles D. Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001:291–309. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frese M., Zapf D. Eine Skala zur Erfassung von sozialen Stressoren am Arbeitsplatz. [A measure of social stressors at work]. Zeitschrift für Arbeitswissenschaft. 1987:134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel A. S., Diefendorff J. M., Erickson R. J. The relations of daily task accomplishment satisfaction with changes in affect: A multilevel study in nurses. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011:1095–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0023937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts S. A., Buunk B. P., Schaufeli W. B. Social comparisons and absenteeism: A structural modeling approach. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994:1871–1890. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00565.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. J., Snell A. F., Foust M. S. Item parceling strategies in SEM: Investigating the subtle effects of unmodeled secondary constructs. Organizational Research Methods. 1999:233–256. doi: 10.1177/109442819923002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam S. A., Ellemers N. Social identity in industrial and organizational psychology: Concepts, controversies and contributions. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2005:39–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., Wolfe D. M., Quinn R. P., Snoek J. D., Rosenthal R. A. Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York, NY: Wiley; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kottwitz M. U., Meier L. L., Jacobshagen N., Kälin W., Elfering A., Hennig J., Semmer N. K. Illegitimate tasks associated with higher cortisol levels among male employees when subjective health is relatively low: An intra-individual analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2013:310–318. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. London: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leary M. R. Making sense of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;(1):32–35. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal G. S. What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In: Gergen K. J., Greenberg M. S., Willis R. H., editors. Social exchange: Advances in theory and research. New York, NY: Plenum; 1980. pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Little T. D., Cunningham W. A., Shahar G., Widaman K. F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2002:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. P., Becker T. E., van Dick R. Social identities and commitments at work: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006:665–683. doi: 10.1002/job.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr G., Müller A., Rigotti T., Aycan Z., Tschan F. The assessment of psychological strain in work contexts: Concerning the structural equivalency of nine language adaptations of the irritation scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2006:198–206. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland R. L., Levine J. M. Sozialization in organizations and work groups. In: Turner M. E., editor. Groups at work: Theory and research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison E. W. Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: The importance of the employee's perspective. Academy of Management Journal. 1994:1543–1567. doi: 10.2307/256798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison E. W., Robinson S. L. When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review. 1997:226–256. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1997.9707180265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motowidlo S. J., Packard J. S., Manning M. R. Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986:618–629. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niehoff B. P., Moorman R. H. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal. 1993:527–556. doi: 10.2307/256591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D., Elmore K., Smith G. Self, self-concept, and identity. In: Leary M. R., Tangney J. P., editors. Handbook of self and identity. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2012. pp. 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M. C. W., Schaufeli W. B., Buunk B. P. The role of attributions in the cognitive appraisal of work-related stressful events: An event-recording approach. Work & Stress. 1995:463–474. doi: 10.1080/02678379508256893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira D., Semmer N. K., Elfering A. Illegitimate tasks and sleep quality: An ambulatory study. Stress and Health. 2014:209–221. doi: 10.1002/smi.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. L., Gardner D. G. Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management. 2004:591–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo J. R., House R. J., Lirtzman S. I. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1970:150–163. doi: 10.2307/2391486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sabo K. Protecting the professional role. A study to review non-nursing activities and recommendations for change. Canadian Journal of Nursing Administration. 1990:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. L., Graham J. W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002:147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M., Gollwitzer M., Maes J., Arbach D. Justice sensitivity: Assessment and location in the personality space. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2005:202–211. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.21.3.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Strube M. J. Self-evaluation: To thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1997:209–269. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60018-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Beehr T. A. Job control and social aspects of work. In: Peeters M. C. W., de Jonge J., Taris T. W., editors. An introduction to contemporary work psychology. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2014. pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Jacobshagen N., Meier L. L. Arbeit und (mangelnde) Wertschätzung. [Work and (lack of) appreciation]. Wirtschaftspsychologie. 2006:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Jacobshagen N., Meier L. L., Elfering A. Occupational stress research: The “Stress-As-Offense-to-Self” perspective. In: Houdmont J., McIntyre S., editors. Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice. Vol. 2. Castelo da Maia: ISMAI; 2007. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., McGrath J. E., Beehr T. A. Conceptual issues in research on stress and health. In: Cooper C. L., editor. Handbook of stress medicine and health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Meier L. L. Individual differences, work stress, and health. In: Cooper C. L., Campbell Quick J., Schabracq M. J., editors. International handbook of work and health psychology. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Tschan F., Meier L. L., Facchin S., Jacobshagen N. Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behavior. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2010;(1):70–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00416.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semmer N. K., Zapf D., Dunckel H. Assessing stress at work: A framework and an instrument. In: Svane O., Johansen C., editors. Work and health – Scientific basis of progress in the working environment. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 1995. pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S., Frese M. Stress in organizations. In: Schmitt N. W., Highhouse S., editors. Industrial and organizational psychology (Handbook of Psychology. 2nd ed. Vol. 12. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. pp. 560–592. [Google Scholar]

- Spector P. E., Brannick M. T. Methodological urban legends: The misuse of statistical control variables. Organizational Research Methods. 2011:287–305. doi: 10.1177/1094428110369842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stets J. E. Examining emotions in identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;(1):39–56. doi: 10.1177/019027250506800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker D., Jacobshagen N., Semmer N. K., Annen H. Appreciation at work in the Swiss armed forces. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 2010;(2):117–124. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J. P., Wagner P. E., Hill-Barlow D., Marschall D. E., Gramzow R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996:797–809. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taris T. W., Kompier M. A. J. Cause and effect: Optimizing the designs of longitudinal studies in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress. 2014;(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2014.878494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. On merging identity theory and stress research. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1991:101–112. doi: 10.2307/2786929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler T. R., Blader S. L. The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003:349–361. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Yperen N. W. Communal orientation and the burnout syndrome among nurses: A replication and extension. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996:338–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01853.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warr P. Work, happiness, and unhappiness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer P. S., Keller A. C., Gardner D. H., Semmer N. K. Challenge stressors: Longitudinal effects on self attitudes, work attitudes, and health; Paper presented at the 11th Conference of the European Academy of Occupational Health Psychology; London. 2014. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Widmer P. S., Semmer N. K., Kälin W., Jacobshagen N., Meier L. L. The ambivalence of challenge stressors: Time pressure associated with both negative and positive well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]