Abstract

Pattern recognition receptors are essential mediators of host defense and inflammation in the gastrointestinal system. Recent data have revealed that toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins (NLRs) function to maintain homeostasis between the host microbiome and mucosal immunity. The NLR proteins are a diverse class of cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors. In humans, only about half of the identified NLRs have been adequately characterized. The majority of well-characterized NLRs participate in the formation of a multiprotein complex, termed the inflammasome, which is responsible for the maturation of interleukin-1β and interleukin-18. However, recent observations have also uncovered the presence of a novel subgroup of NLRs that function as positive or negative regulators of inflammation through modulating critical signaling pathways, including NF-κB. Dysregulation of specific NLRs from both proinflammatory and inhibitory subgroups have been associated with the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in genetically susceptible human populations. Our own preliminary retrospective data mining efforts have identified a diverse range of NLRs that are significantly altered at the messenger RNA level in colons from patients with IBD. Likewise, studies using genetically modified mouse strains have revealed that multiple NLR family members have the potential to dramatically modulate the immune response during IBD. Targeting NLR signaling represents a promising and novel therapeutic strategy. However, significant effort is necessary to translate the current understanding of NLR biology into effective therapies.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, Nod-like receptors, inflammasome, IBD

A dynamic balance exists between the commensal flora and host defensive responses in mucosal tissues.1 Indeed, aberrant inflammation in the gut in response to epithelial cell barrier disruption and microbial flora translocation is a defining feature of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathogenesis in genetically susceptible individuals.1 Idiopathic IBD can be subdivided into 2 distinct forms, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are critical for modulating immune system homeostasis in the gut and are essential components in IBD pathobiology. There are 4 major classes of PRRs associated with IBD, including the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing (NLR) family, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like Helicase receptors, and C-type lectin receptors.2 Together, these receptor families detect pathogens and damage or stress through the recognition of highly conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). After activation, PRRs contribute to IBD pathogenesis by directly or indirectly modulating inflammatory signaling cascades and can also regulate cell proliferation, cell survival and death, tissue remodeling and repair, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).3 Robust PRR activation is essential for proper host-pathogen interactions and driving the mucosal immune response after PAMP and DAMP exposure. However, persistent and/or chronic dysregulated PRR stimulation results in significant collateral tissue damage that contributes to chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, and tumorigenesis in the gut. Thus, PRRs are stuck in what has been described as a “Goldilocks conundrum” where expression, activation, and repression must be constantly kept in check and balance by the host to promote gastrointestinal homeostasis.4

The majority of studies evaluating PRR signaling in IBD have focused on TLR signaling and regulation. However, new insight has revealed that NLR family members significantly contribute, either directly or indirectly, to a variety of processes associated with innate immune responses and IBD pathobiology. In humans, at least 23 NLR and NLR-related proteins have been identified, but only approximately half of the proteins in this family have been functionally and mechanistically characterized.5–7 In the gastrointestinal system, NLRs are regarded as sentinel innate pattern recognition receptors responsible for sensing the microbiota and mediating immune tolerance. Genetic predisposition to IBD in human populations has been linked to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in several NLRs, most notably NOD1, NOD2, and NLRP3. However, cell specificities and mechanisms of immunoregulation by NLRs are not well characterized in humans or in prevalent animal models of IBD.

Although the identification and physical characterization of NLRs have been evaluated over the past decade, the clinical relevance of NLRs as modulators of immunity, cell specificities in the gut mucosa, mechanisms of immune modulation, and potential therapeutic targets during IBD remains largely unknown. More importantly, the role of NLRs independent of pathogen recognition, such as their involvement in metabolism, autophagy, and apoptosis, in the onset and progression of IBD remains primarily unreported in human populations. The NLR family can be divided into functional subgroups, which are defined as inflammasome-forming NLRs, non-inflammasome-forming NLRs, and negative regulatory NLRs. This review focuses on our current understanding of emerging concepts associated with NLR family members within these functional subgroups and their contribution to IBD pathogenesis. To expand on these emerging concepts, we also perform a retrospective analysis on publicly available microarray data sets from patients with UC in a concerted effort to better elucidate dysregulated NLR expression in patients with IBD. The review also comprehensively and systematically discusses and integrates clinically relevant findings posed in the present literature regarding NLR-dependent immunity during IBD.

INFLAMMASOME-FORMING NLRs

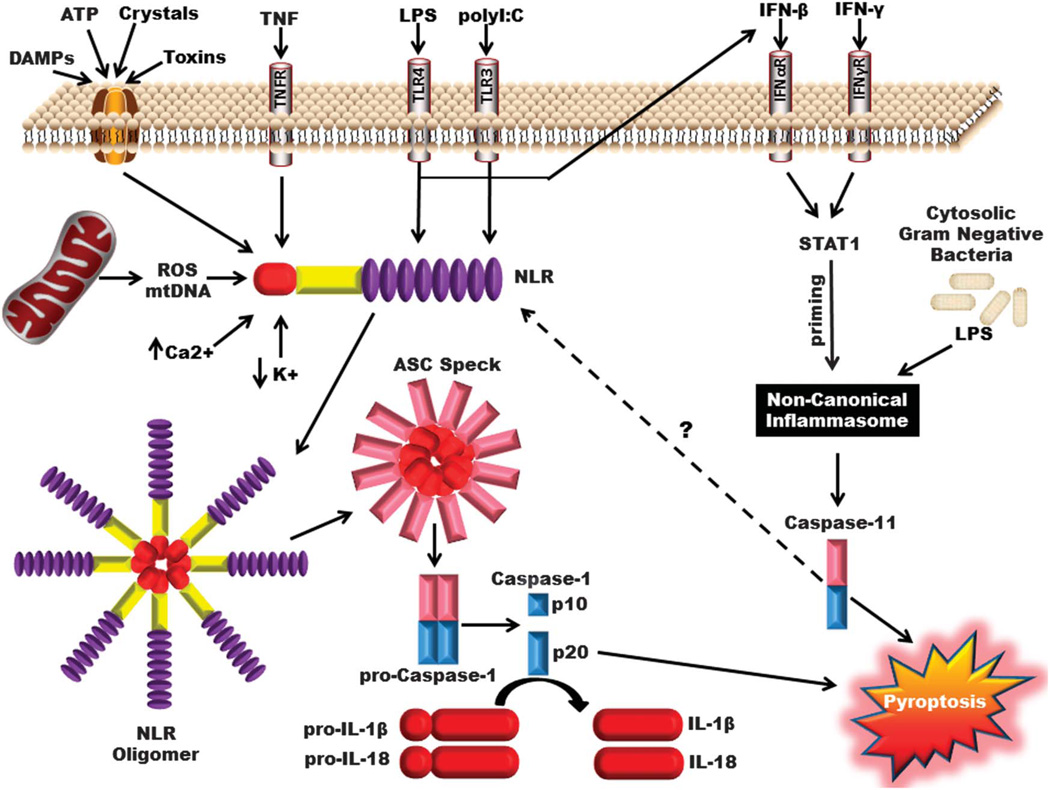

Inflammasomes are macromolecular platforms in the cytosol that recognize PAMPs and DAMPs.8 The formation of the inflammasome leads to the proteolytic activation of caspase-1. Active caspase-1 leads to the maturation of pro-interleukin (IL)-1β and pro-IL-18 into mature and bioactive cytokines (Fig. 1). Inflammasome activation can also lead to a unique form of proinflammatory cell death, defined as pyroptosis and/or pyronecrosis.10–15 The inflammasome is comprised of a NLR(s), the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain [CARD]) and Caspase-1. Several NLRs have been shown definitively to form inflammasome complexes, including NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP6, and NLRC4.16,17 Other less well-defined NLR family members have been shown to either contribute to inflammasome formation or be active in highly specific cell type-, species-, or temporal-specific mechanisms. These lesser defined NLRs include NAIP5, NLRC5, NLRP7, and NLRP12.18–25 Different PAMPs and DAMPs are sensed by individual NLRs, which lead to the formation of a specific NLR inflammasome.6 Mechanisms associated with NLR sensing and activation are currently unclear and remain an area of active investigation. Two distinct mechanisms have been proposed, including direct ligand binding and indirect milieu sensing. It is clear that some NLR and NLR-like proteins participate in direct ligand binding. For example, NAIP5 binds directly to fragments of bacterial flagellin and AIM2 (Absent in melanoma 2) binds directly to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA).18,26–28 However, some NLRs seem to function through indirect milieu sensing. For example, no direct ligand binding has been reported for NLRP3, and the diversity of activators for this particular NLR suggests an indirect sensing mechanism. In this case, NLRP3 has been suggested to sense disruption of the cytosol in response to various agonists, and NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activation has been proposed to be dependent on K+ efflux, generation of mitochondrial ROS, or lysosomal damage and subsequent release of cathepsin B into the cytosol.16

FIGURE 1.

Canonical and noncanonical NLR inflammasome activation. NLR inflammasomes are activated by a diverse range of biological molecules and signaling pathways. Multiple models have been postulated to explain the mechanism underlying NLR sensing and activation, including direct ligand interactions, indirect mechanisms associated with sensing biochemical changes within the intracellular environment, the release of DAMPs due to lysosomal destabilization, and/or pore formation at the plasma membrane that promotes K+ efflux.9 In the canonical NLR inflammasome pathway, the NLR and NLR-like proteins undergo a conformational change after activation that recruits the adaptor protein ASC. ASC serves as a bridge facilitating pro-caspase-1 and NLR oligomerization through CARD-CARD and PYD-PYD domain interactions. NLR inflammasome formation results in the cleavage of caspase-1 into p10 and p20 subunits, which trigger the subsequent cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into the mature cytokines. In the noncanonical inflammasome pathway, the production of IFN-β and/or IFN-γ can sufficiently prime cells in part through STAT1 and induce the formation of a hypothetical noncanonical NLR inflammasome in response to intracellular gram-negative bacteria and LPS.9 Unlike the canonical NLR in-flammasome that cleaves caspase-1, noncanonical inflammasome formation results in the activation of caspase-11. It seems that noncanonical in-flammasome signaling can also induce canonical NLR inflammasome activation and the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 through a currently undefined mechanism. Likewise, both canonical and noncanonical inflammasome formation initiates the unique form of cell death, termed pyroptosis.

The prevailing model of inflammasome activation is supported by data demonstrating homo-oligomerization of NLRs (Fig. 1).29 This oligomerization may occur through single species (AIM2 and NLRP3) or multispecies (NLRC4:NAIP5:NLRP3, NLRP3:NLRC5, and NLRP1:NOD2) NLR interactions.19–21,30,31 In the absence of agonists, NLRs are autoinhibited possibly through direct interaction with the leucine rich repeat and nucleotide binding domain. This interaction may be mediated by binding to deoxyadenosine diphosphate (or deoxyribonucleoside diphosphate) nucleotides.29,32–34 The molecular mechanisms permitting the release of the autoinhibition are not well understood, but it may be governed by exchange of ADP/deoxyadenosine diphosphate for ATP/deoxyadenosine triphosphate or ligand binding. The NLRs can then form wheel-like structures with varying numbers of spokes (Fig. 1).18,29 These wheels can then recruit ASC dimers. These structures have recently been shown to undergo prion-like polymerization to form large filamentous assemblies of ASC and caspase-1 (Fig. 1).35,36 NLR polymerization is mediated through the pyrin domain of the NLR and the pyrin domain of ASC and seems to induce self-perpetuating activation of caspase-1.

Caspase-1 has also been shown to be required for inflammatory cell death programs, termed pyroptosis, which are independent of IL-1β and IL-18. This distinct form of cell death is proinflammatory and has unique morphological signatures that are in contrast to apoptosis. Pyroptosis is characterized by cellular swelling, osmotic lysis, nuclear DNA cleavage, and proteolytic cleavage of glycolytic enzymes.37 Many intracellular pathogenic bacteria have been shown to induce pyroptosis in myeloid cells.14,37 The role of pyroptosis in vivo may limit bacterial replication, expose intracellular pathogens to infiltrating phagocytes, and establish a proinflammatory environment by the release of intracellular proteins.37 The majority of inflammasome-forming NLRs can induce pyroptosis. Pyronecrosis is a caspase-1 independent but NLRP3-dependent cell death pathway that is poorly understood.15 Both pyroptosis and pyronecrosis are understudied in the context of IBD pathogenesis, but are likely contributors to lesion formation.

Several recent studies have shown that NLR inflammasomes function to attenuate IBD. Animal studies using Asc−/−and Casp1/11−/− mice have demonstrated that loss of either of these inflammasome-associated proteins results in significantly increased disease progression in mouse models of experimental colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis.38–45 The majority of recent studies evaluating these NLR inflammasome components have focused on dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) models of experimental colitis. In these studies, Asc−/− and Casp1/11−/−animals were highly sensitive to both acute and relapsing/remitting colitis models. These animals demonstrated significantly increased morbidity and mortality, weight loss, and colon inflammation. Although current data are in agreement, it should be noted that the findings are in contrast to an early study evaluating Caspase-1 in IBD.46 This earlier study actually demonstrated that caspase-1–deficient mice were protected from DSS-driven colitis, and the mechanism was suggested to be due to reduced IL-1β and IL-18 production.46 There are many potential explanations that have been proposed for the apparent discrepancies between the early studies and the more current findings, including differences in experimental design and methods, reagents, gut microbiome, and mouse strains. However, regardless of the underlying cause for the result discrepancies, the current consensus data across multiple independent research groups support a protective role for Caspase-1 in experimental colitis.38,39,45,47,48

ASC and Caspase-1 function through similar mechanisms to attenuate IBD pathogenesis. In both genetically modified mouse lines, there is a near complete ablation of IL-1β and IL-18 in the colon. IL-1β and IL-18 are both related IL-1 cytokines and are both highly associated with IBD pathogenesis. IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that is predominately produced by leukocytes and modulates biological functions of both immune and epithelial cells in the gut. Dysregulation of IL-1β is highly associated with a diverse spectrum of autoimmune diseases. In the context of IBD, patients with active disease often present with high levels of IL-1β, which functions as a potent stimulator of macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils.49–51 Of specific relevance to IBD, IL-1β also promotes leukocyte migration into the intestinal lamina propria, T-cell activation and survival, and CD4+ Th17 cell differentiation.52–56

IL-18 is also emerging as a primary mediator of IBD pathogenesis. Similar to IL-1β, IL-18 is a potent proinflammatory cytokine and is instrumental in the regulation of CD4+ T-cell responses and Th1 differentiation.57 IL-18 levels are significantly upregulated in subpopulations of patients with IBD, and recent studies revealed an association between SNPs in the promoter region of the human IL-18 gene in UC.58,59 In mouse models, IL-18 overexpression and IL-18 attenuation have both been shown to enhance IBD pathogenesis.48,60–62 These paradoxical findings suggest that IL-18 has multiple positive and negative functions in IBD pathobiology, and that dysregulation can significantly impact disease pathogenesis and health outcomes. The dichotomy between the physiological responses driven by IL-1β and IL-18 in IBD models was originally difficult to reconcile. However, recent studies have revealed that in addition to functioning as a proinflammatory mediator, IL-18 has potent effects on epithelial cell regeneration and repair in the context of IBD.48 Thus, the current hypothesis suggests that the loss of effective barrier function in the context of IL-18 deficiency is more detrimental to mucosal homeostasis than attenuation of proinflammatory functions of IL-1β and IL-18 in the absence of functional NLR inflammasomes.

Although ASC and Caspase-1 are critical for NLR inflammasome formation, it becomes increasingly important to identify the specific inflammasome-forming NLRs associated with immune homeostasis and epithelial barrier integrity in the gut. At least 8 NLR and NLR-like proteins are known to function in inflammasome formation, including NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP7, NLRC4, NLRC5, and the PYHIN family member AIM2. Of these characterized inflammasome-forming NLRs, NLRP3, NLRC4, and NLRP6 have been shown to significantly attenuate IBD pathogenesis.38,39,48,63 Similar to the findings for ASC and Caspase-1, mice lacking each of these respective NLRs also demonstrate enhanced sensitivities in experimental colitis models. However, the phenotypes reported for the Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4−/−, and Nlrp6−/− mice are each less severe than those reported for the ASC and Caspase-1–deficient animals. The reduced severity observed in the NLR-deficient mice is suspected to be due to the significant, but partial reduction of IL-18 levels in the colons from each of the individual NLR-deficient animals, as opposed to the complete ablation observed in the Asc−/− and Casp1/11−/− mice. Together, these data indicate the possibility that each NLR may function to attenuate IBD pathobiology through context-specific and nonredundant mechanisms described in greater detail below.

NLRP1

The NLRP1 inflammasome was the first to be identified and characterized.8 NLRP1 is activated in response to Lethal Toxin (LeTx) from Bacillus anthracis in rodents, Toxoplasma gondii in mice, and muramyl dipeptide (MDP) in humans.29,64–68 The genomic organization of NLRP1 is varied across species and the species-specific differences in the NLRP1 locus are compounded further by structural variances between the different orthologs. In rodents, there are multiple paralogs of the Nlrp1 gene, including 3 in mice, and these various paralogs are poorly characterized.64 Significant differences also exist in the protein structure of NLRP1 between species. For example, human NLRP1 contains an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD) and a CARD, unlike the mouse counterparts that only encode a C-terminal CARD domain. In mice, the NLRP1a paralog can regulate homeostatic hematopoiesis, whereas the NLRP1b paralog is sensitive to LeTx.64,69,70 LeTx has also been shown to directly cleave rat NLRP1b.70 Interestingly, human NLRP1 can also be cleaved to regulate its activity, and this processing is necessary for inflammasome formation.71,72 Human NLRP1 can bypass the requirement for ASC during inflammasome formation, but the adaptor protein enhances this process in vitro.29 Additional evidence is needed to fully discern the molecular mechanisms that drive NLRP1 in-flammasome activation.

NLRP1 has yet to be directly evaluated in mouse models of IBD. The multiple paralogs of Nlrp1 make this gene difficult to effectively target. However, the generation of mice lacking Nlrp1abc−/− and Nlrp1b−/− have been recently described.65,69 These animals were found to be highly susceptible to T. gondii, which confirms that NLRP1 is important for sensing specific eukaryotic microbes.73 Also consistent with previous in vitro findings, Nlrp1b−/− mice developed attenuated acute lung injury and morbidity after LeTx exposure.65 NLRP1 has a unique expression pattern compared with the majority of other NLRs. Nlrp1 is highly expressed in epithelial cells and in the colon, making it an interesting target for IBD studies. Although exposure to either anthrax or T. gondii are unlikely to influence IBD pathogenesis, it is highly likely that further characterization studies using the Nlrp1-deficient animals will find that this NLR detects a range of additional PAMPs and DAMPs of relevance to IBD pathobiology. Thus, future studies using the Nlrp1−/− animals in models of IBD are of significant interest.

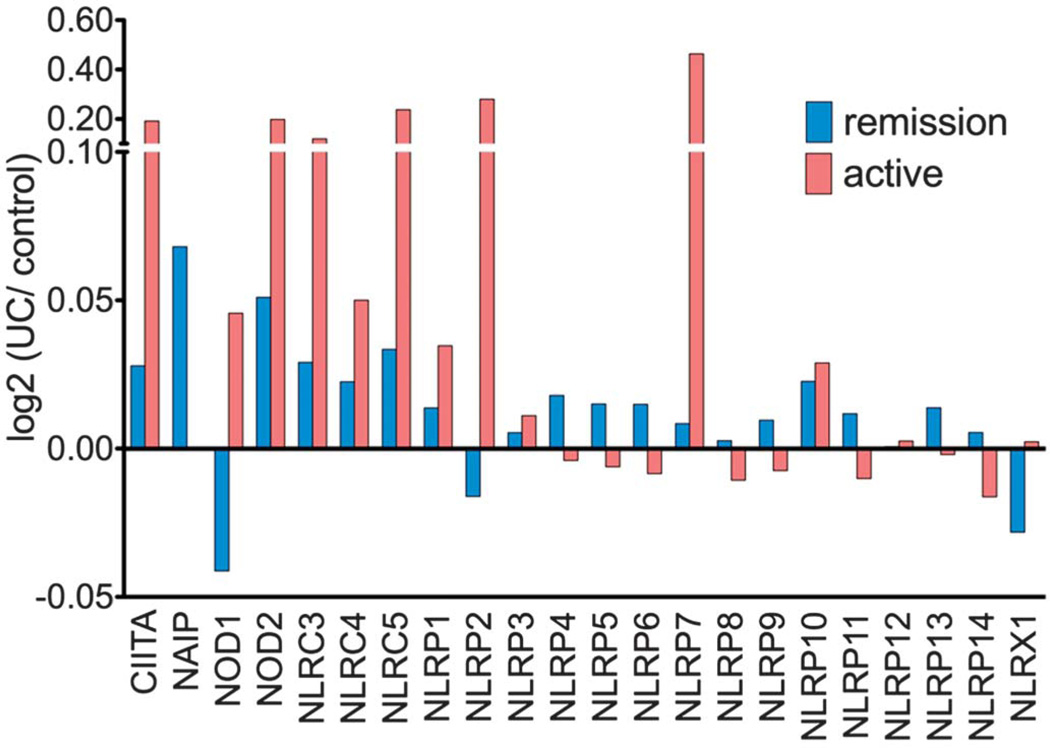

In humans, polymorphisms and mutations within the NLRP1 gene have been associated with several autoimmune and immune dysregulatory diseases, such as vitiligo, celiac disease, type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and others.74–81 Studies of IBD with emphasis on NLRP1 are exceedingly rare. Mutations have been weakly associated with CD through genome-wide association studies with the suggestion that NLRP1 may play a role in extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease (especially skin) and the inflammatory behavior of the disease.82 In a pediatric study, NLRP1 polymorphisms were associated with steroid responsiveness to IBD.83 Peripheral extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, such as dermal erythema nodosum, uveitis, oral stomatitis, and peripheral arthropathy, occur anywhere from 20% to 40% of patients with IBD and wax and wane with disease course, causing sometimes significant worsening of the patients’ quality of life.84–87 Interestingly, we observed increased expression patterns for NLRP1 in colon biopsies from patients with UC in our retrospective gene expression analysis (Fig. 2). NLRP1 may be a molecular bridge between gastrointestinal pathology and extraintestinal manifestations in patients with IBD and provide new avenues to target these widespread and debilitating conditions.

FIGURE 2.

NLR expression in colonic biopsies from patients with UC. Microarray data on colonic biopsies from patients with UC was downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository; accession number GSE38713. Expression values for each gene transcript were averaged between groups. Active versus remissive disease states were determined by endoscopic scoring.88 Patients in remission were in remission for a minimum of 5 months before biopsy and at least 6 months after tissue collection. Data are presented as the log2 fold-change values of diseased tissue compared with healthy control tissue.

NLRP3

NLRP3 is the best-characterized inflammasome-forming NLR. The NLRP3 inflammasome can detect many disparate signals.16 The manifold nature of NLRP3 inflammasome activation has led to the hypothesis that stress recognition is indirectly sensed and direct ligand binding is not favored, but a unifying model remains elusive. Three models have been put forth to explain NLRP3 inflammasome activation. These models are not necessarily exclusive and may ultimately converge on a single pathway. The first model of NLRP3 inflammasome formation is associated with pore formation. Host cells have been shown to sense extracellular ATP, presumably from cellular injury, through the purinergeic ATP-gated channel protein P2X7. This channel allows for K+ efflux and the recruitment of pannexin 1. Pannexin 1 acts as a membrane pore that can allow PAMPs and DAMPs access to the cytosol.89 However, the in vivo significance of this model is not clear because Panx1−/− mice respond normally to NLRP3-dependent agonists.90 Several bacterial pathogens encode pore-forming toxins in their genomes as virulence factors. Possibly in an analogous manner to the P2X7:Pannexin model, these protein toxins can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.91–93 A second model, which is possibly specific to phagocytes, involves phagocytosis of particulate matter, including asbestos, monosodium urate crystals, alum and amyloid β. “Frustrated phagocytosis” of these sterile agonists may cause lysosomal instability and functional impairment.94 Subsequent lysosome damage allows for the release of cathepsin B and other lysosomal proteases into the cytosol where, by some unknown mechanism, they can activate NLRP3 inflammasomes.95,96 The third model of NLRP3 inflammasome activation hinges on the generation of ROS. Interestingly, agonists supporting the first 2 models have also been shown to induce ROS.97–99 Pharmacological blockade of ROS generation and/or ROS scavenging has also shown broad inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome responses.5 ROS production is not sufficient for inflammasome activation because not all ROS generating stimuli activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Thus, there are additional requirements that prime the inflammasome to mount appropriate responses.16 Loss-of-function mutations and gene ablation in the NADPH pathway suggests that alternative sources or locations for ROS are necessary for inflammasome activation.100,101 For example, mitochondrial ROS have recently been implicated in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.102 Interestingly, induction of mitochondrial ROS leads to the recruitment of NLRP3 and ASC from the endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria-associated membranes and activation of Caspase-1.103–106

Similar to ASC and Caspase-1, NLRP3 attenuates IBD pathogenesis in mouse models of experimental colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Nlrp3−/− mice have demonstrated a significant increase in morbidity and mortality, gastrointestinal inflammation, and tumorigenesis in chemical-induced colitis models.38,39,107 Mechanistically, the sensitivity of Nlrp3−/− mice was shown to be associated with a decrease in IL-18 and an increase in epithelial barrier dysfunction.39 Studies using a bone marrow chimera strategy revealed that NLRP3 function was directly associated with the hematopoietic compartment, rather than the stromal or epithelial cells.38 This is consistent with the NLRP3 inflammasome driving the innate immune response to the translocating commensal microbes through the lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells in the colon. Indeed, the loss of epithelial barrier integrity resulted in systemic influx and dispersion of commensal bacteria and resulted in significantly increased leukocyte infiltration into the gut.39 Most of the NLRP3 focus to date has been on T-cell extrinsic mechanisms, whereas little is known about NLRP3 as an intrinsic regulator of CD4+ T-cell differentiation and plasticity.

Several recent studies have sought to characterize the components of the microbiome associated with NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the context of IBD. Most studies have focused on Escherichia coli isolated from patients with IBD, which have revealed that bacteria isolated from an individual patient are closely related and use shared virulence factors.108 However, there seems to be significant differences between strains of E. coli isolated from different patients, suggesting a high degree of genetic heterogeneity.108 The patient-isolated strains of E. coli have all been shown to strongly stimulate NLRP3 inflammasome formation in both macrophages and epithelial cells, and these intracellular E. coli strains survive significantly longer in macrophages.108 Similar findings have also been reported for the probiotic bacterial strain E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) and the commensal E. coli K12, which have also shown differential effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation.109 These studies revealed that EcN induced lower levels of NLRP3 inflammasome activity and IL-18 release in epithelial cells; whereas, K12 induced a robust response and increased autophagy.109 These gut microbiome and E. coli studies suggest that the phenotype observed for Nlrp3−/−mice is strongly associated with the commensal microbial composition. Also of interest, contradictory findings have been reported for all of the NLRs evaluated thus far in IBD models, including NLRP3 and early studies that evaluated Caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18. Thus, these data also suggest that it is highly likely that variations in the microbiome composition are a source for at least some of the contradictory findings reported in the literature.

In humans, polymorphisms in the NLRP3 gene have also been associated with increased susceptibility to CD.110 However, functional mechanisms underlying the role of the NLRP3 inflam-masome in mucosal inflammation and epithelial barrier integrity remain conflicting. For example, a follow-up genome-wide association study was performed, replicating the aforementioned experimental design and reported far weaker associations between NLRP3 SNPs and CD.111 Mechanistically, as characterized by mouse studies, NLRP3 expression in macrophages has been linked to both the attenuation and exacerbation of pathologies caused by experimentally induced colitis.38,47,107 Protection from disease in IBD may be mediated through NLRP3 activation in hematopoietic cells alone (e.g., macrophages).38 Conversely, early initiation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in nonhematopoietic cells (e.g., intestinal epithelial cells) is also essential in mediating disease susceptibility.112 In addition to directly modulating IL-1b/ IL-18, intestinal epithelial cells-derived NLR activation has been associated with the production of inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, and CXCL-1.113 Although unintuitive, heterogeneous results could have large implications in patient-specific therapies and raise consideration for gut microbiome composition, diet, and environmental factors contributing to intrinsic NLRP3 dysregulation. Furthermore, in the case of conflicting genomic results, integrating transcriptomics, proteomics, flow cytometry, and histology data with specific clinical outcomes in patients with well-characterized gene variants through bioinformatics and computational modeling approaches would provide an invaluable assessment of NLRP3 functionality among heterogeneous populations of patients with IBD.

NLRP6

NLRP6 is the most recent NLR to be associated with IBD pathobiology.48 Ectopic and overexpression studies demonstrated that human NLRP6 could interact with ASC and facilitate inflammasome formation.114 In mice, NLRP6 is highly expressed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including epithelial cells and resident macrophages.43,115 Consistent with its expression pattern and role of the other inflammasome-forming NLRs, NLRP6 also exerts strong protective effects in the colon.44,48 Nlrp6−/− mice develop spontaneous colitis and exacerbated DSS-induced experimental colitis.44,48 These mice demonstrate a failure to resolve gastrointestinal inflammation and show significantly attenuated epithelial cell repair due to decreased IL-18 levels in the colon.44,48 In addition to increased colitis, Nlrp6−/−mice also demonstrate exacerbated tumorigenesis in the AOM/ DSS model.44 The increased tumorigenesis in these animals has been associated with decreased epithelial cell repair and increased proliferation. Interestingly, data from bone marrow chimera studies have indicated that the increased tumorigenesis in the Nlrp6−/−mice has been associated with the hematopoietic cellular compartment; however, the severity of colitis seems to be associated with NLRP6 function in the epithelial cell compartment.44,48 Nlrp6−/−mice have a significantly altered commensal microbiome composition compared with wild-type animals, and the gut microflora is directly associated with disease pathogenesis. Both colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis are associated with IL-18 attenuation and microbiome-driven expression of the chemokine CCL5, which drives both inflammation and proliferation of epithelial cells through the IL-6 pathway.42 Fecal transplant/cohousing studies demonstrated that both colitis sensitivity and tumorigenesis were transmissible from Nlrp6−/− mice to wild-type animals.42,48 Likewise, the NLRP6-deficient mice could be protected from IBD when reconstituted with the wild-type microbiome.42 Additional characterization studies have shown that Nlrp6−/− mice are highly resistant to Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, and E. coli.115 However, these animals have significant expansion of the bacterial phyla Bacteroidetes (Prevotellaceae), which was shown to be the primary representative of the microbiota-associated phenotype and directly correlated with IBD pathogenesis.42 Recent mechanistic studies have revealed that Nlrp6−/−mice have defective goblet cell autophagy, which contributes to deficient goblet cell mucin granule exocytosis.116 These data suggest that this defect in mucus production allows Prevotellaceae to colonize atypical locations deep in the crypts of the Nlrp6−/− mice and establish persistent infections that drive colitis. However, despite pioneering work demonstrating the critical role of NLRP6 in regulating commensal ecology in mice, reports translating these results into human populations are lacking. Likewise, the underlying mechanism by which NLRP6 regulates microbial communities remains unclear.

NLRC4

The NLRC4 inflammasome is responsive to a limited set of agonists, including gram-negative bacteria that use type III or IV secretion systems or flagellin.17 In contrast to the NLRP3 inflammasome, the NLRC4 inflammasome can function in collaboration with an additional NLR member(s), NAIP, which dictates ligand specificity.20,117 In this model of inflammasome activation, the ligand bound NAIP protein releases the autoinhibited NLRC4 to allow the large multimeric complex composed of NLRC4:NAIP (plus ligand), ASC, and Caspase-1 to form the resultant inflammasome. Human NAIP (generally a single copy in humans, but in rodents there are multiple copies) seems to have a different specificity of interaction, preferring to bind to the needle proteins of the type III secretion system and not flagellin.117 NLRC4 contains a CARD domain, which should be capable of directly interacting with the CARD domain of Caspase-1. Thus, the role of ASC in NLRC4 inflammasome formation is currently unclear. ASC has been shown to be required for optimal Caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion in response to Shigella flexneri. However, ASC is not required for NLRC4-dependent activation of the inflammasome in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Caspase-1–dependent cell death in response to Shigella.118–120 Also in contrast to some of the other NLRs, NLRC4 inflammasome formation is not dependent on K+ efflux.121 This aspect of NLRC4 activation is possibly due to direct interaction of bacterial PAMPs and NAIP proteins.

Unlike NLRP3 and NLRP6, loss of NLRC4 does not seem to significantly alter immune homeostasis in the gut during models of chemically induced experimental colitis or on administration of a neutralizing antibody targeting IL-10 signaling.38,63 However, Nlrc4−/− mice demonstrate a significant increase in damage to the epithelial cell barrier in the DSS model, which has been attributed to attenuation of IL-18.63 This increased epithelial cell damage is consistent with previous findings that showed an increase in inflammation-driven colon tumorigenesis in the Nlrc4−/− mice.41 Further expansion of these data revealed increased morbidity and mortality in Nlrc4−/− mice in response to flagellated Salmonella infection compared with aflagellate bacteria.63 In addition to Salmonella, NLRC4 has also been shown to be important in the induction of chronic colitis after the colonization of adherent-invasive E. coli during microbiota acquisition in germ-free mice.122 Disease pathogenesis required the adherent-invasive E. coli to be flagellated, which reflects the importance of NLRC4 inflammasome formation in this model.122 Although several studies have identified a clear role for NLRC4 in the discrimination of flagellated and nonflagellated pathogenic stimuli, no studies have directly analyzed the ability for NLRC4 to mediate immune tolerance toward commensal microbiota from humans. Although NLRC4 is elevated in human IBD mucosa in our retrospective analysis, this observation is yet to be validated because no existing reports link genetic abnormalities or expression levels of NLRC4 to IBD (Fig. 2).

NLRC5, NLRP2, NLRP7, AND AIM2

Several less well-characterized members of the NLR family, including NLRC5, NLRP2, and NLRP7 have been shown to form inflammasomes under highly specific conditions. Ectopic and overexpression studies have demonstrated that human NLRC5 could interact with ASC and facilitate inflammasome formation.21–23 In the gut, NLRC5 is predominantly expressed in mucosal B and T lymphocyte populations. NLRC5 has been shown to form an inflammasome after exposure to a diverse set of PAMPs and DAMPs that overlap with NLRP3 sensitivity, leading to the hypothesis that NLRC5 and NLRP3 function synergistically to initiate inflammasome formation.21 However, it should be noted that the function of NLRC5 is currently unclear. In addition to inflammasome formation, NLRC5 has been implicated in the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in major histocompatibility complex class I presentation.123 Likewise, autocrine responses to type I interferons (IFN-I) have also been determined to elicit pronounced effects on NLRC5 activation.124 Although NLRC5 has not been explored in murine or human IBD studies, it is highly probable that this molecule acts as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity at mucosal surfaces. Interestingly, NLRC5 is one of the more upregulated genes in our analysis of transcriptomic profiling (Fig. 2).

NLRP2 and NLRP7 are 2 molecules that were surprisingly upregulated in our retrospective analysis of microarray data from colon biopsies from patients with UC (Fig. 2). Like NLRP6, these 2 molecules have not been explored in the context of human IBD. In fact, little is truly known regarding the roles of NLRP2 and NLRP7 as gastrointestinal immunomodulators.125 NLRP2 has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation while enhancing Caspase-1 activity in human macrophages.126 Interestingly, NLRP2 has also been linked to altered DNA methylation and fetal development.127 Similarly, NLRP7 has been associated with embryogenesis and macrophage immunity toward bacterial stimuli suggesting that NLRP7 could potentially recognize microbial lipopeptides from commensals.24 Interestingly NLRP7 does not exist in the mouse genome and likely arose from a gene duplication in NLRP2. Our analysis suggests that both NLRP2 and NLRP7 could play significant roles in modulating inflammation in active IBD mucosa. However, this hypothesis remains to be explored. In contrast to mice, pigs express NLRP7 and pig models of IBD might be required to study the immunomodulatory actions of NLRP7 during IBD in a model with enhanced translational value.128

AIM2 is a member of the HIN200 family and functions as an NLR-like protein in inflammasome formation.26,27 AIM2 is well-characterized, but has not been evaluated in the context of IBD. AIM2 functions as a dsDNA sensor and has been shown to recognize Francisella tularensis, L. monocytogenes, and a variety of DNA viruses.27,129,130 Likewise, AIM2 also senses host-derived DNA in the cytoplasm and has therefore been strongly implicated in autoimmune disease pathophysiology, including systemic lupus erythematosus.131 Formation of the AIM2 inflammasome in response to either microbe or host-derived dsDNA has strong implications in the context of IBD. Similar to the other inflammasome-forming NLRs, AIM2 is likely to sense specific elements of the host commensal microbiota after translocation and likely contributes to autoimmunity in the gut through the recognition of cytoplasmic dsDNA. Interestingly, cytoplasmic dsDNA has been associated with suboptimal anti-TNF-α therapeutic efficacy in IBD and adverse outcomes in patients with CD, including increased frequency of a lupus-like syndrome.132,133

NONCANONICAL INFLAMMASOMES

Recent studies have characterized a Caspase-11 noncanonical inflammasome that will likely have significant implications in IBD pathobiology. Caspase-1 is exceptionally important in inflammasome formation and function. However, it has recently been determined that the common Casp1−/− mouse strains used in all previous NLR and IL-1β studies were generated from 129 ES cells that are naturally defective in Caspase-11 activity.134 In mice, the Casp1 and Casp11 loci are genetically linked, thus the Casp1 and Casp11 mutations do not segregate by recombination. This has resulted in the realization that previous studies have been using double mutant Casp1−/−/11−/− animals.134 There is currently a significant need to better define mechanisms associated with the biological functions of Caspase-1 and Caspase-11. More specifically, Caspase-11 has recently been shown to function in both Caspase-1-dependent and Caspase-1-independent manners (Fig. 1).134–138 Caspase-11 is critical in the host immune response after exposure to E. coli, Citrobacter rodentium, and V. cholera.134,139 Caspase-11 is also necessary for the activation of caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 maturation. However, Caspase-11-dependent cell death occurs in the absence of Caspase-1. In addition to Capsase-11, Caspase-8 has also been shown to regulate inflammasome function through MALT1 (Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein 1) or TRIF (TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-β).140,141 However, the context in which Caspase-8 inflammasomes are activated is not clearly defined.142–146

NON-INFLAMMASOME-FORMING NLRS

Although a diverse range of NLR family members fall into this functional category, NOD1 (NLRC1) and NOD2 (NLRC2) are the most relevant to IBD pathogenesis. NOD1 and NOD2 are best characterized as intracellular sensors of bacterial peptidoglycan-derived molecules, including meso-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and MDP, respectively.147 In the absence of overt activation through microbial infection, NOD1 and NOD2 are thought to remain in an autoinhibited state. Based on deletion constructs and overexpression data, one model posits that the leucine rich repeat sterically inhibits homo-oligomerization.147–150 A recent crystal structure of NLRC4 further supports this model, in which the leucine rich repeat forms in the shape of an inverted question mark to make specific contacts on the nucleotide binding domain.33 In general, the molecular mechanisms of autoinhibition and regulation are not clearly defined for NLR proteins. The mechanism underlying the temporal regulation of the nucleotide-binding cycle and ligand binding/pathogen sensing in association with specific NLR proteins is complex and may vary greatly.29,32,34 NOD1 recognizes and binds directly to ieDAP (D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid) as the minimal activating motif.34,151 NOD2 has been shown to bind directly to MDP.32,152,153 The cytosolic delivery of bacterial ligands is a necessary prerequisite for NOD activation. Several experimental lines of evidence have reported a variety of mechanisms associated with ligand entry into cells. For example, invasive bacteria, such as Listeria and Shigella, can directly introduce peptidoglycan and breakdown products into the host cell cytosol.154 Additionally, extracellular bacteria can use secretion systems to transport peptidoglycan along with additional effector molecules into the cytosol.155,156

For noninvasive bacteria, host transport mechanisms have also been described for peptidoglycan-derived NOD agonists. Members of the solute-carrier gene family have recently been shown to facilitate the intracellular presentation of MDP or ieDAP. Specifically, SLC15A1, SLC15A2, SLC15A3, and SLC15A4 have been shown to deliver NOD ligands. 157–162 In support of this mechanism, Slc15a3 and Slc15a4 deficient myeloid cells show a paucity of NF-κB-dependent cytokine secretion in response to MDP stimulation.162–164 SLC14A3 and SLC15A4 are localized to the endolysosomal compartments, which supports a specialized role for the endomembrane system in pathogen detection and recruitment of signaling molecules.161 Additional research has supported a general role of endocytosis in the delivery of NOD ligands to the cytosol. In myeloid and nonhemato-poietic cells, clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been shown to allow access of MDP.162,164

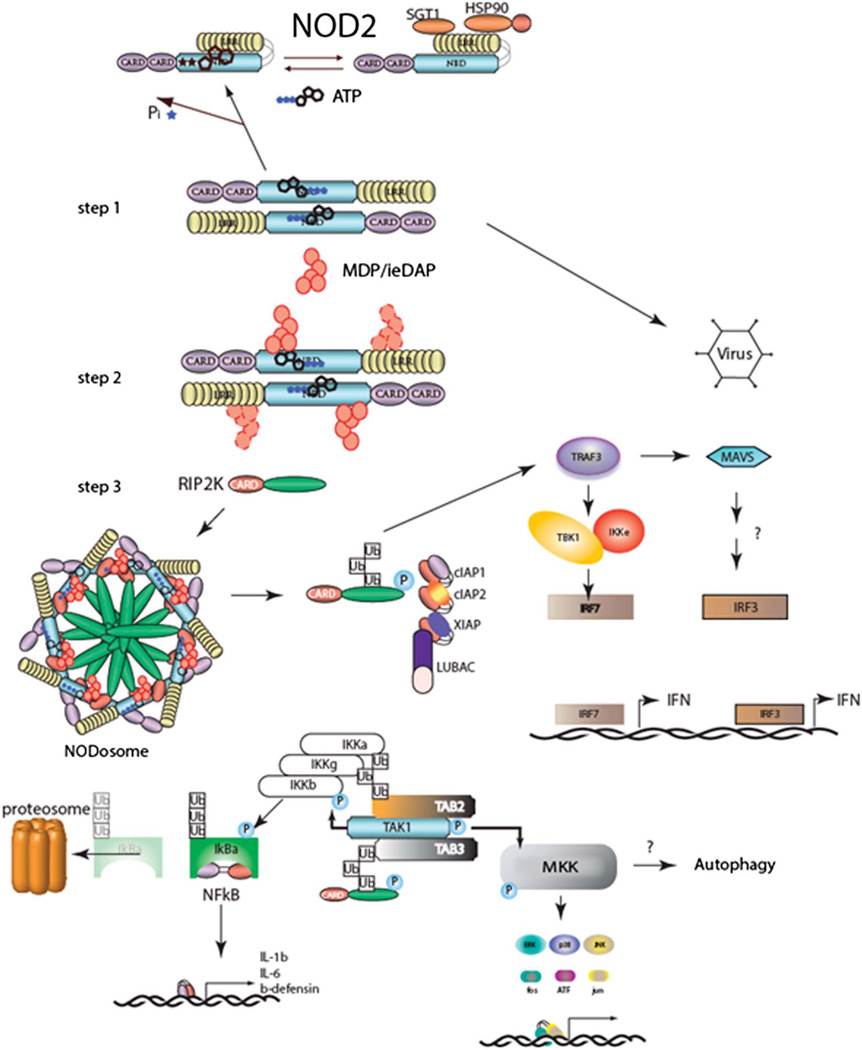

Considerable research has begun to elucidate the sub-cellular distribution of NOD2 during bacterial infections. Evidence is mounting that NOD proteins are redistributed during infection. In the absence of stimulation, NOD proteins reside in the cytosol. On activation, presumably through ligand binding or nucleotide exchange, NOD proteins can relocate to the plasma membrane, autophagasomes, and/or tight junctions. 165–167 However, the mechanisms underlying redistribution is currently unclear, and additional studies are warranted to highlight the molecular mechanisms that drive differential subcellular localization of the NOD proteins. Activation of the NOD1 and NOD2 pathway nucleates the formation of a large macromolecular complex termed the “NODosome” (Fig. 3).168 Presumably, homo-oligomerization facilitates the formation of a platform to recruit additional signaling molecules. Current data support a model by which RIP2, Receptor Interacting Serine/Threonine-protein kinase 2 (also known as CARDIAK, RIPk2, RICK, and CLARP) is recruited through homotypic CARD:CARD (Caspase activation and recruitment domain) interactions between NOD2 and RIP2.169 This recruitment is hypothesized to activate RIP2 through a close proximity model.170 RIP2 recruitment and activation is likely a keystone event in the NOD pathway.171,172 Activation of RIP2 then activates several nonoverlapping pathways, including NF-κB, MAP kinase, and autophagy.170,171,173,174

FIGURE 3.

NOD signaling pathways. The current model suggests that NOD proteins are kept in an inhibited state possibly through autoinhibition or through protein–protein interactions. The mechanisms of the release of inhibition (step 1) are not well understood, but may require the exchange of deoxyadenosine diphosphate for deoxyadenosine triphosphate and ligand binding (step 2). RIP2 is then recruited through homotypic CARD:CARD interactions to a large macromolecular complex termed the NODosome (step 3). Ultimately, RIP2 autophosphorylates at tyrosine X. Active RIP2 is then K63-ubiquitinated on lysine 209 through the E3 ligases cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP. XIAP recruits the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex LUBAC. The TAK1:TAB complex is recruited to the activated ubiquitinated RIP2 protein and undergoes autophosphorylation and K63-linked ubiquitination. This complex then promotes the activation of the IKK complex. IKKγ/NEMO is K63-linked ubiquitinated allowing for the phosphorylation of IKKα and IKKβ. The catalytic subunits of IKK then phosphorylate IĸBα, which leads to its degradation through K48-linked ubiquitin-mediated proteosomal degradation. The release of inhibition allows for NF-ĸB to translocate into the nucleus to activate gene transcription. NOD-dependent activation of RIP2 can also activate MKK through the TAK1:TAB protein complex. Activation of this pathway leads to the mobilization of the activator protein 1 family of transcription factors. Additionally, the interferon regulatory factor pathway can be activated through TNF receptor associated factor 3. The interferon regulatory factor pathway is less well understood. NOD2 can also activate the autophagic response, which is dependent on RIP and the MAPK pathway.

Activation of the NF-κB pathway through NOD ligands is initiated through K63-ubiquitination of RIP2.175–177 RIP2 has been shown to interact with many E3 ligases that promote ubiq-uitination of NEMO/IKKγ (NF-κB essential modulator/inhibitor of NF-κB kinase inhibitor subunit γ) and RIP2.178–181 This poly-ubiquitin network on RIP2 and NEMO recruits TAK1 (transforming growth factor b-activated kinase), TAB2 (TAK1-binding protein 2), and TAB3 (TAK1-binding protein 3).182 This multimeric complex can phosphorylate the IKK complex (inhibitory kB kinase).183 The active IKK complex can then phosphorylate the inhibitor of NF-κB:IκBα. Phosphorylated IκBα is then targeted by K48-ubiquitination for proteasomal degradation by SCF/BTrCP E3 ligase. NF-κB subunits can translocate into the nucleus to drive transcription of NF-κB–dependent genes. Ubiquitination also mediates the downregulation of NOD signaling. TNF receptor associated factor 4 (TRAF4) has also recently been shown to bind to NOD2 and modulate its activation.184,185 Additionally, the HECT E3 ligase ITCH ubiquitinates autophosphorylated RIP2 and inhibits the pathway.186 Likewise, the ubiquitin ligase and editing enzyme A20 has been shown to negatively regulate RIP2 and the IKK complex by means of different mechanisms.187–189

The MAP kinase pathway is also activated in response to NOD ligands through TAK1, which is a protein that activates MAPKK 6 to then activate p38, extracellular-signal regulated kinase, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase to induce activator protein 1-dependent transcription.183,190,191 Several additional pathways have been shown to be active during NOD ligand stimulation. For example, empirical evidence has demonstrated that NOD2 interacts with the mitochondria antiviral signaling (MAVS) protein to promote interferon regulatory factor 3-dependent activation of IFNs in response to RNA viruses and Helicobacter pylori.192,193 NOD proteins also enhance autophagy in myeloid cells. Both MDP and ieDAP can induce autophagy.174,194,195 The role of autophagy in innate immunity is gaining traction as an essential modality in host pathogen interactions. One current model posits that the NOD proteins interact with ATG16L and are essential for autophagosome formation and subsequent pathogen clearance.196

Despite the early interest in NOD1 and NOD2, the mechanism associated with the function of these NLRs in IBD has yet to be fully resolved. This is, in part, due to seemingly contradictory evidence generated in both mouse and human studies. Several distinct transgenic and loss-of-function mouse lines have been generated to evaluate NOD1 and NOD2 function in IBD. The first described Nod2−/− mice failed to develop spontaneous gastrointestinal inflammation.197 However, primary cells isolated from these animals failed to produce proinflammatory responses after MDP stimulation.197 Subsequent NOD1 and NOD2 mice also failed to develop spontaneous IBD symptoms, but were shown to have increased sensitivity to various bacteria species of clinical relevance to IBD. In general, these increased sensitivities have been associated with a failure to effectively clear bacteria after exposure and an inability to initiate an effective immune response due to attenuated production of proinflammatory mediators.156,191,198 Although these animals do not seem to develop spontaneous colitis, the majority of data have demonstrated that both Nod1−/− and Nod2−/− mice are more susceptible to chemical- and antigen-induced experimental colitis.199–202 For example, Nod2−/− mice have been shown to have attenuated NF-κB activation and reduced production of antimicrobial a-defensins in the intestine, which is similar to the observations from patients with IBD carrying mutations in NOD2.203–205 Conversely, NOD2 has also been shown to function as negative regulators of TLR signaling in response to commensal bacteria translocation. Nod2−/−mice demonstrated increased proinflammatory mediators associated with Th1 differentiation and enhanced NF-κB activation after TLR2 stimulation.206 TLR2 ligand administration effectively diminished chemically induced colitis through a NOD-dependent mechanism and reconstitution of NOD2 into the Nod2−/− mice resulted in colitis attenuation.206 Nod1−/−/Nod2−/− mice have also been evaluated in the context of IBD and were found to be highly susceptible to experimental colitis.207 The double knockout mice display reduced epithelial barrier function and increased commensal bacteria translocation.207 Studies using these Nod1−/−/Nod2−/− mice have revealed that colitis sensitivity can be partially alleviated by altering the host microbiota composition or feeding the mice the probiotic bacterium Bifido-bacterium breve.207 These conflicting animal model data echo the current controversy in humans as to whether NOD2, and to a lesser extent NOD1, mutations attenuate or enhance their functional activities in the context of IBD and underscore the complex nature and incomplete understanding of these NLRs in gastrointestinal health and disease.

In humans, NOD2 is the most studied NLR associated with IBD. Three common mutations at the leucine-rich repeat, as well as, over 2 dozen rare mutations and polymorphisms have been associated with increased risk of CD across many studies, with up to a 20-fold risk increase in homozygotes.208–213 Patients with CD who carry NOD2 mutations are more likely to require small bowel surgery than noncarriers, with homozygotes additionally tending to require surgery earlier than heterozygotes, suggesting a gene-dosage effect.214 NOD2 mutations are also associated with stricturing disease, a particularly troublesome complication of CD.215 Overall, the strongest phenotypic locale associated with NOD2 is ileal disease.216 Most of these mutations occur in people of European descent. The resulting core effects of these mutations remain to be discovered because the debate between a loss-of-function and a gain-of-function and specific cellular and molecular targets continues to be unresolved. However, some correlations between NOD2 and various components of the gut have been made. For example, NOD2 has been implicated in autophagy regulation placing it among several other susceptibility loci for CD that have similar relationships to cellular debris processing, as well as, de-fensin production, and other crypt antimicrobial functions.174,217 Altered NOD2 status is also associated with altered microbiota in patients with IBD.218,219 Although the relationship between genetic alteration of NOD2 and IBD has been well proven, studies have yet to demonstrate a clear connection between these genetic alterations and clinical response to treatment. This area represents an opportunity to evaluate additional pathways surrounding NOD2 and determine functional targets that may be upstream or downstream. Given that microbiota plays a large role in IBD, there is also a great deal on untapped potential in determining how NOD2 performs these functions.

NOD1 mutations have been inconsistently associated with IBD in various studies. The most positive study done by McGovern et al220 suggested the association of the deletion variant of an intronic polymorphism through transmission disequilibrium testing and case-control analysis. They observed distortion of transmission of this NOD1/CARD4 variant in IBD and UC, but failed to show the same in CD. Follow-up SNP analysis showed significant associations with IBD and early-onset CD, but not UC, and demonstrated a gene-dosage effect of the deletion with age of onset. Another group also found a correlation between NOD1 variants and early-onset IBD.221 However, studies by Tremelling et al, Franke et al, Van Limberg et al, and others failed to show significant associations.222–225 NOD1 is still considered a strong candidate for involvement in the pathogenesis of IBD given its regulation of the innate immune response, particularly regarding its interaction with TLRs, which sense the microbial population. Given that dysbiosis is an important factor in IBD, studies of NOD1 may need to progress past the genetic level and focus more on mechanistic and functional analyses.

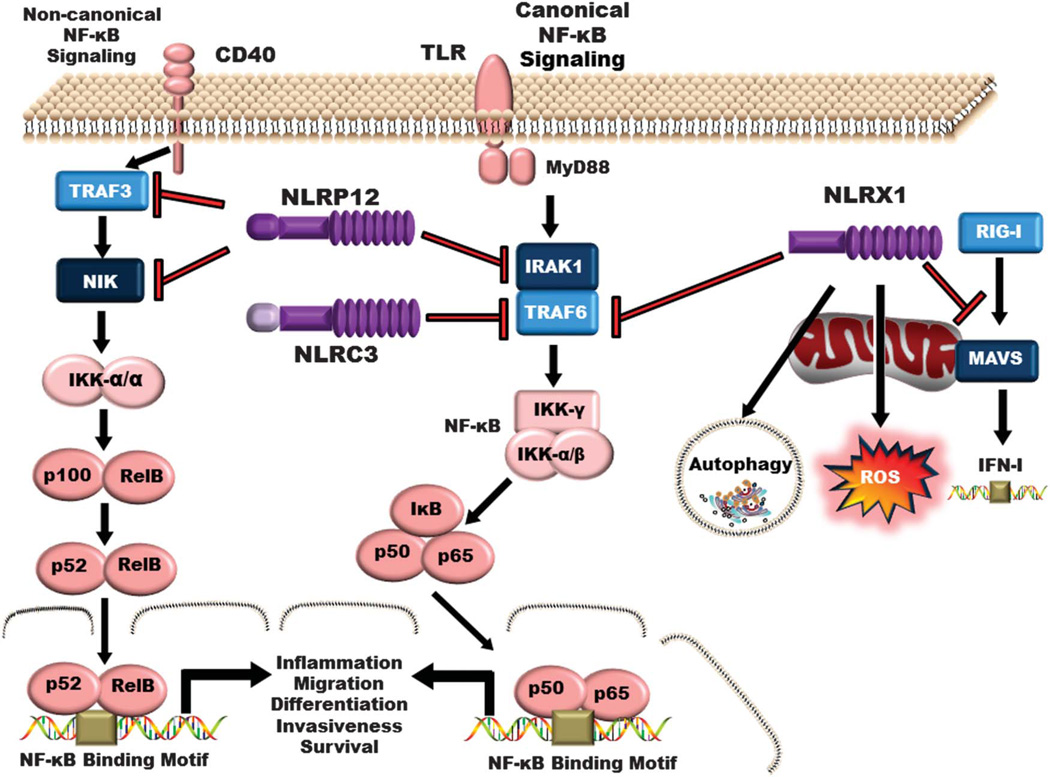

NON-INFLAMMASOME FORMING INHIBITORY NLRS

A subgroup of NLR proteins have recently been shown to negatively regulate immune signaling pathways. This subgroup currently includes NLRC3, NLRX1, and NLRP12. These NLRs act as inflammatory thermostats and function through diverse mechanisms to attenuate overzealous inflammation. However, all 3 NLRs in this subgroup converge on the NF-κB signaling pathway to negatively regulate inflammation by targeting critical elements of either the canonical or noncanonical cascade (Fig. 4). For example, all 3 proteins have shown the capacity to interact with members of the TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF) family, and bioinformatics studies have revealed the presence of multiple TRAF binding sites associated with NLRs in this functional subgroup. This has led to the emerging hypothesis that these NLRs function to form a multiprotein complex, tentatively described as a “TRAFasome.226” However, more mechanistic studies are necessary to validate this intriguing concept. In addition to negatively regulating NF-κB signaling, members of this subgroup have also been shown to modulate IFN-I signaling, autophagy pathways, and ROS production (reviewed in Ref. 4). Regardless of the ultimate mechanism, the ability of these NLRs to modulate overzealous inflammation has clear implications in IBD pathogenesis. Additional mechanistic insight associated with the NLRs in this functional subgroup will be essential for the development of future therapeutic strategies.

FIGURE 4.

Non-inflammasome-forming inhibitory NLR signaling. After TLR stimulation, canonical NF-κB signaling is negatively regulated by NLRX1 and NLRC3 through interactions with TRAF6 and the IKK complex. NLRP12 functions as a negative regulator of canonical NF-κB signaling through a mechanism associated with modulating IRAK-1 phosphorylation. NLRP12 has also been shown to be a potent-negative regulator of non-canonical NF-κB signaling through interactions with NIK and TRAF3. In addition to directly modulating NF-κB signaling, NLRX1 and other members of this NLR subgroup have also been shown to negatively regulate type-I interferon (IFN-I) signaling and function as positive regulators of cellular processes, including autophagy and ROS production.

NLRC3

NLRC3 is the most recently characterized non-inflammasome-forming NLR and negatively regulates the canonical NF-κB signaling cascade and the IFN-I pathway. NLRC3 was originally described as a negative regulator of NF-κB in human T lymphocytes. NLRC3 was shown to negatively regulate CD25, IL-2, NF-κB, nuclear factor of activated T-cells, and activator protein 1.227 The preferential expression of NLRC3 in lymphocytes and its ability to modulate IL-2 secretion has led the authors to speculate a unique role for this NLR in adaptive immunity.227 The generation of Nlrc3−/− mice provides an excellent tool to dissect the cell-type–specific role of this NLR.226 Indeed, bone marrow-derived macrophages from Nlrc3−/− mice are hypersensitive to TLR stimulation with LPS. These cells secrete more NF-κB-dependent cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12. Additionally, these cells show an increase in K63-ubiquitin-linked TRAF6, suggesting that NLRC3 affects TRAF6 stability.226 The role of lymphocyte-specific NLRC3 function remains uncharacterized.

The Nlrc3−/− mice were recently used to investigate the role of NLRC3 in detecting cytosolic DNA in macrophages.228 Cytosolic dsDNA, herpes simplex virus 1 infection, and cyclic dinucleotides derived from bacteria have been shown to induce IFN-I secretion and represent PAMPs derived from intracellular bacteria and DNA viruses. NLRC3 was shown to directly interact with STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) through its nucleotide binding domain, which was analogous to NLRC3 interactions with TRAF6. The STING:NLRC3 complex inhibits the translocation of STING from the endoplasmic reticulum to puncta at or near the perinuclear region and the interaction between TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase-1) and STING, suggesting a mechanism to inhibit IFN-I production.228 Nlrc3−/− mice are resistant to infection with herpes simplex virus 1 suggesting that NLRC3 may act as an attenuator of inflammation.228 How NLRC3 may function in different pathologies remains to be fully explored. There are no studies to date on the association of NLRC3 with IBD or with NLRC3 mutations within the human population in general. NLRC3 shows potential in in vitro studies to be a negative regulator of inflammation and assessment of its activity and function during IBD may provide another therapeutic target. Because other NLRs in this subgroup seem to perform similar functions through TRAF6 interactions, it is possible that these NLRs provide support for one another and perform interrelated functions in dampening the immune response.

NLRX1

NLRX1 is a mitochondrial-associated NLR and was originally proposed to function as a molecular brake to attenuate inflammation after pathogen exposure.229 NLRX1 was shown to interact with MAVS and RIG-I to inhibit IFN-I production in response to viral PAMPs and single-stranded RNA viruses.229,230 Indeed, a recent crystal structure demonstrates that NLRX1 can bind directly to single-stranded RNA.231 In addition to negatively regulating IFN-I, this NLR also inhibits NF-κB signaling through interactions with TRAF6 and IKK.232 NLRX1 is ubiquitinated during stimulation with LPS, which causes it to dissociate from TRAF6. Once liberated, NLRX1 binds to the IKK complex to inhibit downstream NF-κB-dependent cytokine transcription. NLRX1 also regulates autoph-agy in response to viral infection.233 NLRX1 interacts with TUFM (a mitochondrial translation elongation protein) to facilitate autophagosome formation through the ATG5:ATG12: ATG16L complex.233 In this instance, NLRX1 acts as a positive regulator. Interestingly, autophagy can also directly inhibit the IFN-I response, which provides another possible route, whereby NLRX1 may negatively mediate the host antiviral response. NLRX1 has also been shown to regulate mitochondrial ROS through interactions with the respiratory complex in the mitochondrial matrix.234,235 This has been shown in vivo after infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Specifically, C. trachomatis infection in mice demonstrates an NLRX1-dependent ROS production, which facilitates enhanced growth and survival.236 Thus, NLRX1 function is highly complex and incompletely understood. Indeed, the localization and function of NLRX1 has been the subject of intense debate. NLRX1 was initially shown to localize to the mitochondrial outer membrane where it inhibited NF-κB and IFN-I responses to viruses.229,230,232 However, subsequent to the initial characterization, another group demonstrated that NLRX1 localized to the mitochondrial matrix and regulates ROS.234,235,237 These seemingly contradictory data may reflect complex shuttling of NLRX1, as seen with CIITA and NLRC5, and its promiscuity in binding partners suggests that it can function as a scaffolding platform to negatively regulate disparate pathways.

There are no studies to date on the association of NLRX1 with IBD or with NLRX1 mutations within the human population in general. However, this molecule represents an avenue of high therapeutic potential for IBD and other immune-mediated disorders. NF-κB strongly influences mucosal inflammation in IBD and given that NLRX1 is a regulator of that pathway, it would be wise to pursue as a potential therapy. NLRX1 association with mitochondria and its effects on ROS also provide a novel avenue by which to study IBD pathogenesis. Mitochondria, ROS, and cellular oxidative stress have been increasingly implicated in IBD, but have proven mechanistically difficult in terms of having predictive value.238–246 Targeting of mitochondria and ROS may be extremely beneficial. Indeed, a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant formula MitoQ has already been shown to suppress colitis in animal models and human monocyte-like cell lines through suppressing NLRP3.247 NLRP3 may have interactions with NLRX1 as well. The adaptor protein MAVS promotes NLRP3 localization to the mitochondria and inflammasome formation, whereas NLRX1 interacts with MAVS in an inhibitory manner. This push-and-pull dynamic between NLRs may well be more widespread that currently known. A variety of available drugs have been shown to suppress ROS. However, there is a huge potential for both emerging drugs targeting oxidative metabolism and inflammation, as well as, dietary and nutraceutical antioxidant therapy. Thus, the association of this gene with other autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases may provide a bridge to link changes in ROS with IBD and other disorders.

NLRP12

NLRP12 functions as a negative regulator of innate immunity and has been shown to inhibit both the canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathway248–254 (Fig. 4). NLRP12 was shown to negatively regulate the noncanonical NF-κB pathway through interactions with NIK and TRAF3 in vitro and in vivo.252,255 The interaction between NIK and NLRP12, possibly stabilized by HSP90, facilitates the degradation of NIK and the subsequent attenuation of the pathway.248 Additionally, NLRP12 can also inhibit canonical NF-κB signaling by modulating IRAK1 phosphorylation during TLR stimulation and infection with Mycobacteria tuberculosis.254 Although somewhat controversial, it should be noted that NLRP12 has also been implicated in inflammasome formation in overexpression studies and under highly specific pathogenic conditions.25,251,252,256–259

Recent mouse studies evaluating NLRP12 have revealed that this NLR plays a significant role in protecting the host from IBD pathogenesis. Nlrp12−/− mice develop severe gastrointestinal inflammation in DSS models of colitis and increased tumorigenesis in AOM/DSS models.39,252 The Nlrp12−/− mice develop extensive epithelial cell damage and loss of barrier integrity after DSS administration.39,252 This results in increased production of cytokines and chemokines and eventually leads to significantly increased inflammation.39,252 The increase in IBD pathogenesis in the Nlrp12−/− mice has been attributed to increased NF-κB and extracellular-signal regulated kinase signaling.39,252 These findings are highly consistent and quite complementary between the independent groups that have evaluated NLRP12. However, it should be noted that a few mechanistic differences underlying NLRP12 function have been proposed. In one study, the increased colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis was shown to be associated with increased canonical NF-κB signaling.39 After PAMP stimulation, this study noted a significant increase in p-p105, Rel-A, and p65 activity in Nlrp12−/− mice and macrophages.39 This increase in canonical NF-κB signaling resulted in a significant increase in proinflammatory mediators associated with IBD, including increased Il-6, Tnf-α, and Cox2 transcription. These data are consistent with the findings from the initial studies evaluating NLRP12 in human cell lines. In these early in vitro studies, NLRP12 was shown to attenuate TLR- and TNFR-mediated inflammatory signaling pathways antagonizing IRAK-1 hyperphosphorylation.254 In the second study, the increase in colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis in the Nlrp12−/− mice was found to be associated with increased noncanonical NF-κB signaling.252 This study demonstrated that NLRP12 protects the host during IBD through interactions with TRAF3 and the suppression of NIK activity. In the absence of NLRP12, NIK activity was significantly increased, and p100 to p52 cleavage was more robust in primary cells and colon tissues collected from Nlrp12−/− mice after DSS and AOM/DSS exposure. The increased disease activity was further associated with a significant increase in the expression of noncanonical NF-κB chemokines, including Cxcl12 (SDF-1) and Cxcl13 (BLC).252 NF-κB signaling is complex and heavily regulated. The overall findings associated with NLRP12 in IBD are consistent between all of the current studies. Likewise, the apparent discrepancies mentioned in the underlying mechanisms can be reconciled by considering previous findings that the canonical NF-κB pathway and MAPK signaling can be significantly influenced by noncanoncial NF-κB signaling.260,261

In humans, mutations in NLRP12 are associated with familial periodic fever syndrome and cold-induced autoinflammatory disease.262–264 In a study by Borghini et al,264 monocytes isolated from humans with NLRP12 mutations did not show increased NF-κB activity after stimulation with TNF-α or at baseline. However, these monocytes did show significantly increased kinetics of IL1-β secretion, which were more than twice that of controls. NLRP12 mutant monocytes from these patients also produce increased ROS during resting phase and compensate poorly (high antioxidant upregulation, but rapid exhaustion) when stimulated with LPS. In addition, the patient with the highest disease activity showed the highest increase in IL-1b kinetics and ROS production, whereas a milder case showed more subtle changes. In the mouse studies, CXCL12 and CXCL13 were both found to be significantly upregulated in the absence of NLRP12.252 CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 are critical for maintaining homeostasis and inflammation in the intestinal mucosa, and polymorphisms in these genes have been linked with IBD in human populations.265 Likewise, CXCL13 and its receptor CXCR5 have been strongly implicated in the formation of aberrant gut-associated lymphoid tissue in human IBD.266 Given that NLRP12 acts in murine studies to suppress colitis, it would be worth investigating the functionality of this gene in greater detail within the context of human IBD.

THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL

As illustrated above, the role of NLRs in immune modulation, host defense and cell death represents an area of intense investigation in biomedical research and potential value in trans-lational medicine. However, the mechanisms of sensing, priming, and immune modulation by NLRs are incompletely understood. For instance, little is known about the modulation of adaptive T-cell responses by NLRs expressed in myeloid, epithelial, or T cells across spatiotemporal scales, as well as, T-cell intrinsic versus extrinsic mechanisms. In addition, the pharmacological modulation of NLR pathways is still in its infancy. Regarding this, most of the progress made in NLR-related therapeutic discovery and development has focused around NOD1 and NOD2, whereby selective inhibitors of these receptors (i.e., 2-aminobenzimidazole and purine-2,6-dione for NOD1 and benzimidazole diamides for NOD2) have already been identified.267 There are also some natural products (i.e., curcumin, parthenolide, and the polyunsaturated fatty acids Docosahexaenoic acid and Eicosapentaenoic acid) that may nonselectively inhibit NOD oligomerization, in part, by preventing the formation of disulfide bonds joining NACHT domains. Conceptually, inhibition of the NLR effector pathways should be beneficial in the context of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, whereas NLR agonists could enhance effector responses to microbial pathogens and fight infection. However, because of the complexity of innate immune networks, inhibition of NOD1 and NOD2 whether selective or not will likely impair host defense and raise questions about safety, particularly in the face of chronic administration in IBD.

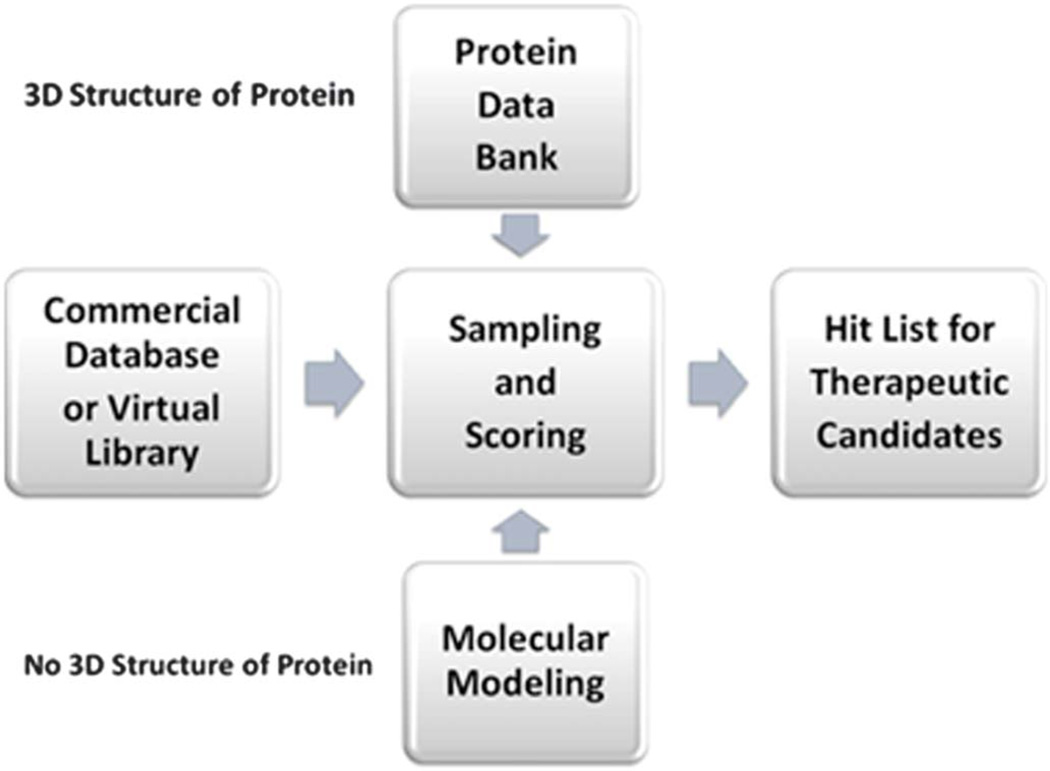

Because of their crucial role in modulation of host responses to infection, stress, and injury, NLRs represent ideal targets for development of novel therapeutics for infectious, immune-mediated, and chronic inflammatory diseases. However, for the most part, they are not fully validated targets and additional development is required to advance NLR pathways and respective lead compounds along the regulatory pathway. Also, although some selective inhibitors are available, to date, no small molecules targeting the NLR pathway have received investigational new drug (IND) approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Targeting activation of regulatory NLRs, such as NLRX1, as opposed to suppressing effector and/or inflammasome-forming NLRs, has the potential to minimize adverse side effects while achieving downmodulation of excessive immune responses during IBD. Only 6 NLRs (e.g., NOD1, NOD2, NLRP3, NLRC4, NLRP6, and NLRP12) have been reported in the context of the IBD literature,38,41,48,252,268 most of which have been explored solely in murine models. Importantly, our preliminary data mining efforts identify 21 NLRs as altered at the messenger RNA level during active disease in colons of patients with UC (Fig. 2). It is unknown whether dysregulated NLR functions are inherent or acquired, but they consistently surface during expression profiling efforts suggesting an important immunomodulatory role during IBD. Molecular modeling approaches represent efficient and cost-effective ways to identify new compounds that bind to NLRs and exert potent anti-inflammatory effects during IBD.

The predominant technique used in the identification of new ligands is the physical large scale, high-throughput screening of thematic compound libraries against a biological target, which is very costly and yields mixed results. Recent successes in predicting new ligands and their receptor-bound structures make use of structure-based virtual screening (SBVS), which is a more cost-effective approach in drug and natural product discovery. The basic procedure of SBVS is to sample binding geometry for compounds from large libraries into the structure of receptor targets by using molecular modeling approaches. Each compound is sampled in thousands to millions of possible poses and scored on the basis of its complementarity to the receptor. Of the hundreds of thousands of molecules in the library, tens of top-scoring predicted ligands are subsequently tested for activity in experimental assays (Fig. 5). We plan to perform SBVS to identify new ligands of NOD-like receptors (NLRs). One of the main requirements for SBVS is the availability of the 3-dimensional structure of a validated protein target. The crystal structures of some NLRs have been determined by experiments, which are published in the Protein Data Bank (PDB),269 including NAIP (PDB ID: 2VM5), NOD1 (PDB ID: 2NSN), NLRC4 (PDB ID: 4KXF), NLRP1 (PDB ID: 4IFP), NLRP4 (PDB ID: 4EWI), NLRP7 (PDB ID: 2KM6), NLRP10 (PDB ID: 2M5V), NLRP11 (PDB ID: 2 L6A), and NLRX1 (PDB ID: 3UN9). For those NLRs whose crystal structures are unknown, computer-modeled structures could be used for virtual screening. We have successfully identified novel immune modulators by using computer-modeled SBVS.270,271 In combination with surface plasmon resonance validation, molecular modeling approaches are a valuable first step towards NLR-targeted drug discovery. The compounds with greater binding affinity can then be advanced to in vitro and in vivo studies in animal models of IBD, safety studies in rats, as well as, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion studies.

FIGURE 5.

Pipeline of SBVS. Novel drug candidates can be identified through SBVS by synergizing information from several publicly available databases, existing thematic compound libraries, and software pipelines. During this iterative process, the target protein structure must be obtained first either from the protein data bank or predicted using molecular modeling. Potential compound properties are obtained next from commercial databases or a virtual library. Using a robust molecular docking protocol, compounds are computationally sampled and scored ultimately resulting in the generation of a top hit list of lead compounds to be advanced towards in vitro testing, as well as, efficacy, and safety studies.

Predicting IBD prognosis is patient-specific, time-sensitive, and often elusive yet crucial for deciding effective treatment and disease control. Mathematical and computational modeling offers a novel perspective for identifying molecular targets aimed at the development of more efficacious and safer personalized interventions for IBD. Publicly available microarray studies offer robust data sets for calibrating, or fitting, mathematical equations to observed biological phenomenon. Models engineered from data-rich signaling networks offer invaluable predictive power for hypotheses that are experimentally challenging. For example, multiscale modeling offers a feasible means to study the combined effect of modulating cytokine production, NLR expression, and microbiome composition for IBD treatment, whereas laboratory procedures could not reasonably explore these compounding factors. Therapeutic targeting of NLRs and the inflammasome in IBD has been hindered in part because mechanisms of sensing, priming, activation, and signaling are incompletely understood at the systems level. Computational modeling could be used to investigate cell specificity of NLRs and the role of NLRs in sensing dysbiosis in addition to mechanisms underlying modulation of T-cell differentiation by dysregulated NLR signaling. Computational modeling should be considered in future perspectives of IBD therapy development for elucidating the complex interplay between immunity, metabolism, and the microbiota, as well as, provide insight on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic regulation of new IBD therapies.

In summary, targeting NLRs to suppress gut inflammation and tissue damage represents a promising novel therapeutic avenue in IBD. However, significant effort is needed to translate the current understanding of NLR biology into new safer and more effective therapies for IBD and other immune-mediated diseases. Combining experimental, bioinformatics, and computational modeling approaches, such as molecular modeling and systems modeling, has the potential to accelerate NLR-targeted drug development for IBD. These multidisciplinary modeling approaches are well suited to predict binding affinities of new compounds to specific NLRs, investigate how key lead families modulate immunological networks, address issues associated with cell specificities (e.g., epithelial cells, myeloid cells and T-cell subsets), and elucidate mechanisms of IBD therapeutic efficacy of new lead compounds within the gut mucosa.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, NIDDK (K01DK092355, ICA), NIAID (HHSN272201000056C, JBR), and NCI (R21CA131645, BKD); the Virginia Tech Nutritional Immunology and Molecular Medicine Laboratory; and the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM-IRC, ICA).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh D, McCarthy J, O’Driscoll C, et al. Pattern recognition receptors- molecular orchestrators of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutikhin AG, Yuzhalin AE. Inherited variation in pattern recognition receptors and cancer: dangerous liaisons? Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:31–38. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S28688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen IC. Non-inflammasome forming NLRs in inflammation and tumor-igenesis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ting JP, Davis BK. CATERPILLER: a novel gene family important in immunity, cell death, and diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:387–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, et al. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen H, Miao EA, Ting JP. Mechanisms of NOD-like receptor-associated inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2013;39:432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]