Abstract

Background

Many studies have measured the intensity of end of life care. However, no summary of the measures used in the field is currently available.

Objectives

To summarise features, characteristics of use and reported validity of measures used for evaluating intensity of end of life care.

Methods

This was a systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. We performed a comprehensive literature search in Ovid Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews and reference lists published between 1990-2014. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, full texts and extracted data. Studies were eligible if they used a measure of end of life care intensity, defined as all quantifiable measures describing the type and intensity of medical care administered during the last year of life.

Results

A total of 58 of 1590 potentially eligible studies met our inclusion criteria and were included. The most commonly reported measures were hospitalizations (n = 44), intensive care unit admissions (n = 39) and chemotherapy use (n = 27). Studies measured intensity of care in different timeframes ranging from 48 hours to 12 months. The majority of studies were conducted in cancer patients (n = 31). Only 4 studies included information on validation of the measures used. None evaluated construct validity, while 3 studies considered criterion and 1 study reported both content and criterion validity.

Conclusions

This review provides a synthesis to aid in choosing intensity of end of life care measures based on their previous use but simultaneously highlights the crucial need for more validation studies and consensus in the field.

Introduction

As the world’s population ages, research on end of life care is increasingly important. Healthcare expenditures in the last year of life are, on average, five times higher than in other years [1]. Health services near the end of life are often responsible for much of the increased costs since many patients die in acute care settings [1, 2]. Efforts to improve end of life care require accurate measurement of the care provided.

Healthcare costs at the end of life are directly related to the intensity of care. Intensity of end of life care is usually highest in hospital settings. Evidence suggests that in the days just before death patients commonly receive invasive or life prolonging procedures. For example, studies have shown about half of patients at the end of life receive mechanical ventilation, undergo chemotherapy, and a quarter receive cardio pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [3–6]. Although these practices are common, they do not always align with patients’ preferences.

Nearly 40% of patients die in acute care hospitals [7]. Yet studies report between 45%-86% of patients at the end of life say they would prefer to die at home [7–10]. End of life treatments may be more influenced by factors like local practice patterns and number of hospital beds than by patients’ preference [10–13]. Consideration of costs and clinical outcomes are key to understanding the quality of end of life care, however, appropriateness of care is ultimately judged by patients’ preferences.

Previous studies have highlighted issues that arise when measuring end of life care [14, 15]. Defining the end phase of life can be ambiguous and terms are often used differently between clinical settings, healthcare professionals and researchers. There are many different illness trajectories for dying people, and there is no accurate clinical indicator to predict time of death [16, 17]. As a result definitions for the end of life phase vary considerably. Furthermore, in order to measure intensity of care at the end of life, it is essential to first define what is meant by both intensity and end of life care. Intensity of care attempts to identify high levels of utilization and not to merely quantify healthcare use. End of life care generally considers all health care administered in a distinct timeframe before death. It is often used interchangeably with various other terms such as palliative care, hospice care, or terminal care [18]. This lack of agreement presents methodological challenges when conducting and comparing end of life research [19, 20].

Despite these challenges many studies have measured the intensity of care at the end of life [11, 21–23]. However, researchers disagree on the standards of measurement, and no overview of the measures used in the field is currently available [21]. A plethora of measures have been used in previous research—most commonly high usage of hospitals, the number of physician visits, CPR, mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, and chemotherapy near the end of life [21, 24, 25].

Studies of the intensity of end of life care require reliable and valid measures that work in different care settings, populations and diseases. However, it is currently unclear what tools have adequate validity and should be recommended for measuring intensity of end of life care. In this systematic review, we provide a comprehensive overview of the measures of intensity of end of life care that are currently used in published original research. We summarize their features (i.e., type of measures) and describe characteristics of their use (i.e., population, timeframe) and reported validity.

Methods

The methods to identify, select, and critically appraise the relevant studies in this systematic review are reported according to the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines [26].

Definition

We defined measures of intensity of end of life care as all quantifiable measures describing the type and intensity of medical care administered during the last year of life. We included the following categories of care: hospitalizations (acute hospital, intensive care unit [ICU]; emergency department [ED]); potentially life-sustaining invasive procedures which include a range of treatments administering complex, invasive methods to prolong a person's life (e.g., resuscitation, intubation, and mechanical ventilation, artificial feeding, dialysis); and potentially life-prolonging treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, medical imaging, transfusions).

Literature search and eligibility criteria

Studies were included in this systematic review based on the following criteria: (1) used a measure that met our definition and (2) explicitly stated they were measuring intensity of end of life care. We included cohort studies (prospective and retrospective), case-control studies, and randomised-controlled trials. We included all studies that used the term intensity or a synonym (intensive, aggressive, extensive) or that indicated they were quantifying higher or increased levels (frequencies, rates) of end of life care. We searched for studies reporting measures of intensity of end of life care in adults aged 18 or older. We excluded studies on children and patients with mental illness because these population groups have different care needs and thus may require different measures of intensity of care. We also excluded studies that: (1) did not include a clearly defined end of life timeframe (e.g. measured within 30 days before death); (2) reported exclusively on cost; (3) included exclusively clinical palliative care; (4) evaluated only outpatient settings; (5) were case reports; or (6) were published before 1990.

OVID Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews were searched to identify studies from 1 January 1990 up to 29 January 2014. We used the following key words: end of life care; last year of life; last months of life; terminal care; terminally ill; critically ill; palliative care; treatment intensity; intensity of care; intensity of treatment; aggressiveness of care; amount of care; health services utilization. A specific search strategy was developed for each database. No language restrictions were applied. We identified additional studies by hand-searching the reference lists of included studies. Appendix 1 provides detailed information on search terms.

Two reviewers (X.L. and M.M.) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. Disagreements about inclusion and exclusion were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer (K.C.).

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted the following information for each study: author; year of publication; country; aim; design; details on the study populations (disease, age, and gender); setting (e.g., emergency department, intensive care unit); and a description of the measure. When studies used more than one measure, or included more than one population (multiple comparison groups), we only extracted data on the measures that met our inclusion criteria.

We developed an individualized assessment checklist that included both validation of individual measures and criteria for quality of methods used. We extracted data on the validity of measures [27, 28], including face and content validity (measure covers the domains considered to be important, assessment is based on the subjective views of experts); criterion validity (measure correlates with another instrument that measures similar aspects, preferably a reference standard or one that is widely used and accepted in the field); and construct validity (measure conforms with the results using other established scales or different groups of patients).

We rated the quality of evidence as: “good” (reported measure validity, measure was used in other studies, well-described study design, thorough assessment of potential sources of bias well documented strengths and limitations); “moderate” (no reported measure validity and met three or more other criteria); and “low” (no reported measure validity and met less than three other criteria). We contacted developers of measures and sought additional information on validity of measures. Two reviewers (X.L. and M.M.) independently extracted data from each included study.

Results

Identification of eligible studies

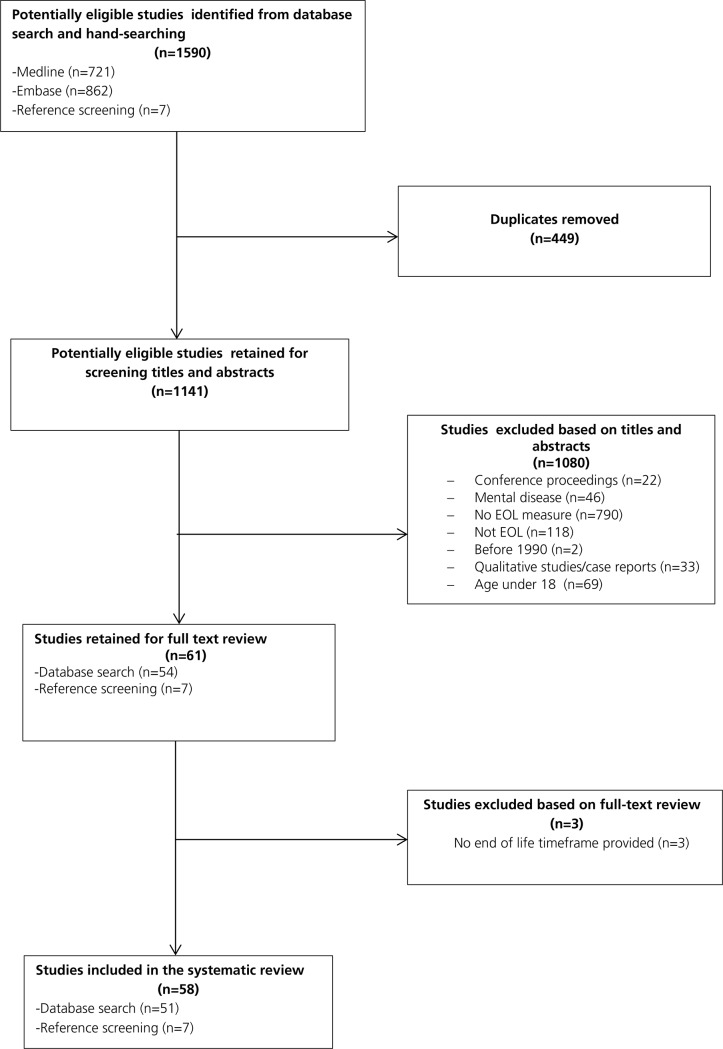

We identified 1590 potentially eligible studies and included 58 studies that met our inclusion criteria and described measures of intensity of end of life care in the last year of life (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Identification of eligible articles on measures of intensity of end of life care.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies are provided in Table 1. The majority of studies were in populations aged 65 years and older. Only four studies were gender-specific (i.e. males alone). Three were prospective cohort studies, 53 retrospective cohort studies and two were randomized controlled trials. Almost all studies relied on administrative data. Study aims were heterogeneous. Twenty-four studies looked explicitly at the measures of intensity of care. The remaining studies did not have intensity of care as a primary aim but met our definition (Table 1). They evaluated health care utilization/care patterns at the end of life (n = 17), variation of end of life care across different settings, populations and time trends (n = 14), or evaluated quality of end of life care (n = 3). Studies measured intensity of life care over different timeframes ranging from hours to months, in disease-specific populations (including cancer, heart failure, other chronic disease [e.g., respiratory diseases, end stage renal disease], trauma, multiple diseases [e.g., hip fracture, COPD, colorectal cancer and acute myocardial infraction]) and non-disease-specific populations (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Aim | All studies(%) (n = 58) |

|---|---|

| Intensity of care | 24 (41.4) |

| Health care utilization | 17 (29.3) |

| Time trends in end of life care | 14 (24.1) |

| Quality of end of life care | 3 (5.2) |

| Year | |

| 1990–1994 | 2 (3.4) |

| 1995–1999 | 1 (1.7) |

| 2000–2004 | 4 (6.9) |

| 2005–2009 | 21 (36.2) |

| 2010–2014 | 30 (51.7) |

| Country | |

| Asia | 4 (6.9) |

| Australia | 1 (1.7) |

| Europe | 8 (13.8) |

| Northern America | 45 (77.6) |

| Study design | |

| Prospective cohort study | 3 (5.2) |

| Retrospective cohort study | 53 (91.3) |

| Randomised controlled trials | 2 (3.4) |

| Validity | |

| Criterion validity | 3 (5.2) |

| Content and criterion validity | 1 (1.7) |

| Summary score | |

| Included a | 2 (3.4) |

| Minimum age for inclusion (years) | |

| 18+ | 4 (6.9) |

| 60+ | 30 (51.7) |

| Other b | 24 (41.4) |

| Disease | |

| Cancer | 31 (53.4) |

| Chronic diseases c | 5 (8.6) |

| Heart failure | 2 (3.4) |

| Trauma | 1 (1.7) |

| Multiple diseases d | 3 (5.2) |

| Non-disease specific | 16 (27.6) |

| End of life timeframe | |

| ≤1 month | 23 (39.7) |

| 2 months | 1 (1.7) |

| 3 months | 1 (1.7) |

| 6 months | 18 (31.0) |

| 12 months | 15 (25.9) |

| Number of measures reported in each study | |

| Single measure e | 7 (12.0) |

| More than one measure (range 2–46) | 51 (87.9) |

| Quality of evidence | |

| Good | 9 (15.5) |

| Moderate | 46 (79.3) |

| Low | 3 (5.1) |

aOne study included six individual measures (chemotherapy use, >1 ED visit, >1 hospital admission, >14 days in hospital, >1 ICU admission, or death in hospital), and one study included seven individual measures (ICU admission, ICU LOS, intubation and mechanical ventilation, haemodialysis, tracheostomy, gastrostomy).

bReported age as mean and median.

cChronic diseases (e.g., respiratory diseases, end—stage renal disease).

dHip fracture, COPD, colorectal cancer and acute myocardial infraction.

eIncluded only one measure (e.g., radiotherapy use, chemotherapy use).

Types of measures

We organized measures into three key domains of end of life care: hospitalizations, life-sustaining invasive procedures and life-prolonging treatments. The majority of studies used more than one measure. Table 2 provides an overview of the measures by domain with descriptions of each measure.

Table 2. Summary of intensity of end of life care measures from included studies.

| Category of care | Description of measures | N | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of hospitalizations(count, mean, median, %, rate, SD, categorical yes/no) | 44 | [11, 12, 23, 24, 40–79] | |

| Number of hospital re-admissions (count) | |||

| Admitted to the hospital (yes/no) | |||

| Hospital LOS (days, months, median, categorical cut—off e.g.>1 >2, >14 days) | |||

| ICU admission (count, median, [IQR], rate, %, SD, yes/no) | 39 | [11–13, 21–24, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 52–59, 65–68, 72–86] | |

| Hospitalizations | Any ICU admission (count) | ||

| ICU LOS (days, mean, median, categorical yes/no, categorical cut-off e.g., 0, 1, ≥2) | |||

| ICU admission during hospital stay (yes/no) | |||

| Terminal ICU admission (rate, %) | |||

| ED visits (mean, %, rate, categorical yes/no, categorical cut off of ED visits) | 24 | [24, 40, 41, 47–51, 53–55, 57, 65–67, 71, 74–76, 79, 80, 84, 85, 87] | |

| ED with and without hospital admission (categorical yes/no) | |||

| Intubation/mechanical ventilation (categorical yes/no, rate, %) | 17 | [13, 21–23, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 66, 68, 72, 77, 82, 83, 86, 87] | |

| Ventilator days (count of days) | |||

| Life-sustaining procedures | CPR (median, mean, categorical yes/no, %) | 9 | [21, 23, 45, 48, 51, 58, 66, 68, 72] |

| Feeding tube placement (rate, categorical yes/no, %) | 10 | [13, 21, 23, 45, 51, 58, 68, 72, 82, 83] | |

| Tracheostomy (rate, categorical yes/no, %) | 6 | [21, 22, 45, 72, 82, 83] | |

| Dialysis (rate, categorical yes/no, %) | 10 | [21, 22, 51, 72, 78, 82, 83, 86–88] | |

| Chemotherapy (count, categorical yes/no, %) | 27 | [24, 43, 47–51, 53–55, 57, 58, 62, 65–68, 72–76, 80, 84, 85, 87, 89] | |

| Intravenous chemotherapy (median, range, mean, SD) | |||

| Oral chemotherapy (median, range, mean, SD) | |||

| Average number of chemotherapy cycles* (%) | |||

| Average number of chemotherapy regimens* (%) | |||

| Life-prolonging treatments | Blood transfusion (%, categorical yes/no) | 2 | [72, 87] |

| Receipt of radiotherapy (categorical yes/no, %) | 10 | [41, 43, 48, 49, 51, 53, 76, 80, 87, 90] | |

| Radiotherapy days (count of days) | |||

| Underwent medical imaging (categorical yes/no) | 5 | [13, 48, 56, 72, 87] | |

| Surgical interventions (diagnostic, curative, elective, palliative (yes/no) | 8 | [11, 13, 41, 43, 45, 46, 49, 51] | |

| Surgical admissions (mean, yes/no, %) | |||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; ED, emergency department; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay.

*Chemotherapy regimens include treatment plans (e.g. type of drugs, instructions on when the drug should be taken) whereas chemotherapy cycles include the time of chemotherapy treatment and the break before the next chemotherapy.

Hospitalizations

Measures focusing on hospitalizations were most widely reported (n = 44). They were used most commonly in cancer patients (n = 22), with fewer studies in groups with other illnesses. Intensity of end of life care was reported as number of hospitalizations (count, mean, median, percentage, standard deviation [SD], categorical yes/no), number of re-admissions (count), and hospital length of stay (LOS: count of days, months, median, categorical cut-off e.g. >1, >2, >14 days).

We identified 39 studies that measured intensity of ICU use in the last months of life, as ICU admissions (count, median interquartile range [IQR], rate, %, SD) or ICU LOS (count of days, median, categorical cut-off e.g. 0, 1, ≥2 days). Emergency department (ED) admissions were reported in 24 studies, as ED visits (mean, percentage, rate) or ED admissions (with and without hospital admission) and cut-offs of ED visits in the last month of life (0, 1, 2, ≥3).

Potentially life-sustaining invasive procedures

Compared with hospitalizations, studies measuring intensity of life-sustaining treatments were less numerous. The most commonly reported life-sustaining treatments were intubation/mechanical ventilation (n = 17), measured as receipt of intubation/mechanical ventilation (yes/no). Other measures included feeding tube placement (n = 10), dialysis (n = 10), CPR (n = 9), and tracheostomy (n = 6). These measures were applied in both disease and non-disease specific populations, but were more widely used in cancer patients.

Potentially life-prolonging treatments

Chemotherapy was the most frequently reported life-prolonging treatment (n = 27), described as chemotherapy use (mean, median, range, standard deviation [SD]), average number of cycles and regimens within the last 3–6 months, or last 7–30 days for a range of cancer types (e.g., prostate, lung, breast, colorectal, gastrointestinal, colorectal). Eight studies evaluated intensity of surgical procedures at the end of life (e.g. general, gynaecologic, orthopaedic, thoracic, and urologic or neurosurgical interventions). One study developed a surgical intensity score defined as the proportion of decedents who received a surgical procedure during the last year of life (e.g., any surgery that involved incision, excision, manipulation, suturing of tissue). Ten studies measured receipt of radiotherapy in the last 14–30 days of life. Other less frequently reported measures were number of blood transfusions, and medical imaging.

The vast majority of studies measuring intensity of life-prolonging treatments reported results using more than one measure (e.g. ICU, ED, and chemotherapy).

Summary score

Two studies reported results based on an intensity of end of life care summary scores (Table 1). Earle et al., (2005) combined six measures (use of chemotherapy, >1 ED visit, >1 hospital admission, >14 days in hospital, >1 ICU admission, or death in hospital) with higher scores (range 0–6) indicating more intensive end of life care. This score was adopted in other studies (Tang et al., 2009). Lin et al., (2009) combined seven measures (ICU admission, ICU LOS, intubation and mechanical ventilation, haemodialysis, tracheostomy, gastrostomy) also with higher scores (range from -2.08 to 3.12) indicating more intensive end of care.

Validity

Four studies involved a panel of experts to assess content validity (n = 3) or criterion validity (n = 1). One study reported both on content and criterion validity. No study reported on construct validity. Earle et al., (2008) explored validity of their intensity of end of life care measures by correlating them with measures of family members’ satisfaction with quality of care near the end of life. The results showed (statistically non-significant) trends toward less satisfaction with care when chemotherapy was administered two weeks before death, death occurred in an acute care setting, or there was no or only a short (≤3 day) hospice stay. Sato and colleagues (2008) assessed content validity and inter-rater reliability using a team of physicians, palliative care doctors and research nurses. Earle and colleagues (2005) used an expert panel of health providers to assess the validity of measures such as chemotherapy, ED/ICU admission, hospitalization, hospice use. Barnato et al., (2009) assessed criterion validity by comparing Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council discharge data (PHC4) intensity of end of life care measures with measures used in the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. The study reported correlations for six measures of the PHC4 (ICU admission, ICU LOS, intubation and mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube placement, haemodialysis) and the four Dartmouth Atlas measures (inpatient reimbursement, hospital days, ICU days, medical doctor visits) in two populations (decedents and patients with a high probability of dying on hospital admissions).

Quality of evidence

We considered the quality of evidence to be good for 9 (15. 5%) studies, moderate for 46 (79.3%) studies and low for 3 (5.1%) studies (Table 1). The most common reason for downgrading the quality of evidence was the lack of validity of measures. There were few studies which we rated as good because the measures were repeatedly adopted in other studies. This was particularly the case with measures developed by Earle et al., (2004) and Earle et al., (2005).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of measures used for evaluating intensity of end of life care. We assessed studies measuring hospitalizations, life-sustaining invasive procedures and life-prolonging treatments in the last 12 months of life. Aims, populations studied, definitions of intensity of end of life care and measures used were heterogeneous across studies. The number of intensity of end of life care studies grew over the last decade with over 50% of the studies included published within the last five years. Our findings show that intensity of end of life care is most commonly evaluated using a combination of measures, including two summary score measures. This review also highlights an important deficit in health services research of end of life care. Measures of intensity of end of life care, although widely used in health services research, lack validation and general agreement by experts in the field. Overall, we consider the evidence to be of moderate quality. It could be argued that the lack of prospective studies reflects the difficulty of conducting research with people who are approaching death [29].

Strengths and weaknesses of the systematic review

This systematic review was based on a comprehensive literature search that resulted in the inclusion of 58 studies that reported on a variety of intensity of end of life care measures. We collected an extensive list of details on the studies and the measures that researchers used. The greatest strength of this systematic review is that it provides a unique and detail-rich overview of measures of intensity of end of life care used in a wide variety of settings.

There is no agreement on the end of life timeframe, which ranges in the literature from hours to months [16]. The World Health Organization [30] has a published a commonly used definition for palliative care, but it includes neither timeframe, nor terminology for intensity of care, nor a definition of end of life care. Previous research also revealed no general agreement on the best interval or measures for identifying end of life care [31]. As a result, we may have missed some potentially relevant studies on end of life care because they did not fall within our strict definition. We also focused only on services, and did not include other settings like outpatient clinics, hospice or home care. We included all studies that met our definition but were unable to account for differences in definition. We recognize that our definition may not be entirely consistent with other definitions of intensity of end of life care. We do not suggest that ours is the best definition but regard it as good working definition that represents a broad set of health services research designed to evaluate the intensity of end of life care.

Challenges in measuring the intensity of end of life care

Our findings should be interpreted carefully, since many of the studies we included did not focus on measuring intensity of end of life care alone. Less than half of the studies we reviewed were based on an explicit definition or primarily aimed to study intensity of end of life care. Many measures included in this review were used to evaluate health care utilization more generally. However, the measures often overlapped despite differences in objectives. Thus it remains unclear if measures developed specifically to assess intensity of care are necessary. Health services utilization measures answer questions about volume of care [32] while measures of intensity of care tend to be more disease specific. For example, measures of aggressiveness of care (e.g. frequent ED visits or hospitalizations, long inpatient LOS) are nearly exclusively used in cancer populations to assess poor quality of end of life care [24]. The paucity of validation studies makes distinguishing between measures and their specific uses difficult. These two sets of measures originate from differences in the purposes of studies (e.g., a health service perspective vs. a clinical perspective). Both sets of measures are potentially useful and a better understanding of which measures should be used in which settings would be instrumental to guiding health service research in the future.

Many of the examined studies actually repeatedly utilize a single measure set, those measures developed by Earle, C.C., et al. (2004). These measures have subsequently been adopted for various uses, including by the American Society of Clinical Oncology's QOPI (quality oncology practice initiative) measure set (http://www.asco.org/). The repeated use of this measure set reflects the influence of these measures, whether or not they have been formally validated.

Our study shows that hospitalization rates at the end of life are high, regardless of the specifications of the measure selected. High number of hospitalizations at the end of life may be related to lack of structure and availability of homecare services. Previous studies suggest that increased end of life homecare services will reduce the demand for acute care services at the end of life as well as improve the quality of life of these patients [24, 33, 34]. Furthermore, treatment delivered at the end of life may also be related to the region of care. [1, 35]. Unfortunately, given the mass of papers from North America and small numbers from other regions it was not possible to adequately examine results by region. There was a different pattern of care for cancer patients than for the non-disease specific group. Measures developed for cancer patients are well documented and over represented in the literature. However, the majority of these studies reuses data primarily collected for administrative purposes thus restricting any potential influence to a non-measurable unsystematic bias.

These measures generally examined the last month of life, when cancer patients are most likely to be hospitalized. The trajectory to death is easier to identify for cancer patients than the trajectory for patients with other diseases, and this may account for the difference. Measures designed for cancer care may not be appropriate for other disease, and more research on end of life measures should be conducted on populations with other diseases like heart failure. However, measures developed for general populations may not be specific enough to identify areas for quality improvement. Measures also vary between countries, perhaps due to the wide range of health policies, and organizational structures, across countries.

Most research on intensity of end of life care is based on retrospective cohort studies that use administrative data because it is only possible to determine the exact period before death retrospectively [15, 20]. Thus, the most readily available sources of healthcare use are administrative datasets. Most studies retrospectively assessed the care received by patients in the time frame before death, but one study identified patients who were entering the terminal phase of disease, and whose probability of death was high, and then prospectively observed patient care forward in time [21, 36]. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. Measures based on treatments given to patients with a high probability of dying may accurately identify end of life patients and be less prone to bias [37, 38]. Researchers argue that, in order for the results to be valid, the care of end of life patients must be captured prospectively [19]. But the higher quality of retrospective data may produce results more useful for monitoring end of life care across providers, geographic areas, demographic groups, and time periods [37].

An analysis of the qualitative literature on the intensity of end of life care was beyond the scope of this study. Several qualitative tools have been developed to measure different aspects of end of life, including quality of life, physical symptom control, emotional and cognitive symptoms, spirituality, grief and bereavement, satisfaction and quality of care, and caregiver well-being [39].

Conclusions

There is no consensus on the definition for intensity of end of life care. The associated measures are seldom validated and often used for varying aims, in differing populations and most commonly in combinations of more than one at a time. Definitions, methods, and strategies all vary across studies and countries. The choice and assessment of measures of intensity of care at the end of life should be based on the aim of the study although which measure suits specific aims best remains unclear. This review is the first to attempt to identify measures used specifically for evaluating intensity of end of life care. It provides a synthesis for choosing measures based on their previous use but also highlights the crucial need for more validation studies.

Supporting Information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 16-803) (www.snf.ch). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kelley AS. Treatment intensity at end of life—time to act on the evidence. Lancet. 2011. Oct 15;378(9800):1364–5. PubMed Epub 2011/10/11. eng. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61420-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Bensink ME, Ramsey SD. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: can we simultaneously increase quality and reduce costs? American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012. Oct 1;186(7):587–92. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3480521. Epub 2012/08/04. eng. 10.1164/rccm.201206-1020CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML. Costs of cancer care in the USA: a descriptive review. Nature clinical practice Oncology. 2007. Nov;4(11):643–56. PubMed . Epub 2007/10/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Le Conte P, Baron D, Trewick D, Touze MD, Longo C, Vial I, et al. Withholding and withdrawing life-support therapy in an Emergency Department: prospective survey. Intensive care medicine. 2004. Dec;30(12):2216–21. PubMed . Epub 2004/11/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Walraven C, Forster AJ, Parish DC, Dane FC, Chandra KM, Durham MD, et al. Validation of a clinical decision aid to discontinue in-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitations. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001. Mar 28;285(12):1602–6. PubMed . Epub 2001/04/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raijmakers NJ, van Zuylen L, Costantini M, Caraceni A, Clark J, Lundquist G, et al. Artificial nutrition and hydration in the last week of life in cancer patients. A systematic literature review of practices and effects. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2011. Jul;22(7):1478–86. PubMed . Epub 2011/01/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Critical care medicine. 2004. Mar;32(3):638–43. PubMed . Epub 2004/04/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forero R, McDonnell G, Gallego B, McCarthy S, Mohsin M, Shanley C, et al. A Literature Review on Care at the End-of-Life in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine International. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abel J, Rich A, Griffin T, Purdy S. End-of-life care in hospital: a descriptive study of all inpatient deaths in 1 year. Palliat Med. 2009 October 1, 2009;23(7):616–22. 10.1177/0269216309106460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wentlandt K, Zimmermann C. Aggressive treatment and palliative care at the end of life A Public Health Perspective on End of Life Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, Barnato AE, Gawande AA, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011. Oct 15;378(9800):1408–13. PubMed English. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, Skinner JS, Sharp SM, Bronner KK. Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. Bmj. 2004. Mar 13;328(7440):607 PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC381130. English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care.[Summary for patients in Ann Intern Med. 2003 Feb 18;138(4):I36; 12585853]. Ann Intern Med. 2003. Feb 18;138(4):273–87. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. George LK. Research design in end-of-life research: state of science. The Gerontologist. 2002. Oct;42 Spec No 3:86–98. PubMed . Epub 2002/11/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teno JM. Measuring end-of-life care outcomes retrospectively. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1:S42–9. PubMed . Epub 2006/02/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Izumi S, Nagae H, Sakurai C, Imamura E. Defining end-of-life care from perspectives of nursing ethics. Nursing ethics. 2012. Sep;19(5):608–18. PubMed . Epub 2012/09/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glare PA, Sinclair CT. Palliative medicine review: prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008. Jan-Feb;11(1):84–103. PubMed Epub 2008/03/29. eng. 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teno JM, Coppola KM. For every numerator, you need a denominator: a simple statement but key to measuring the quality of care of the "dying". J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999. Feb;17(2):109–13. PubMed . Epub 1999/03/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004. Dec 8;292(22):2765–70. PubMed . Epub 2004/12/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gagnon B, Mayo NE, Laurin C, Hanley JA, McDonald N. Identification in administrative databases of women dying of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006. Feb 20;24(6):856–62. PubMed . Epub 2006/02/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CCH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Development and validation of hospital end-of-life treatment intensity measures. Medical Care. 2009. October;47(10):1098–105. PubMed English. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181993191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin CY, Farrell MH, Lave JR, Angus DC, Barnato AE. Organizational determinants of hospital end-of-life treatment intensity. Medical Care. 2009. May;47(5):524–30. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS175740 PMC2825686. English. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819261bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong SPY, Kreuter W, O'Hare AM. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012. 23 Apr;172(8):661–3. PubMed English. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004. Jan 15;22(2):315–21. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langton JM, Blanch B, Drew AK, Haas M, Ingham JM, Pearson SA. Retrospective studies of end-of-life resource utilization and costs in cancer care using health administrative data: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014 May 27. PubMed 24866758. Epub 2014/05/29. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009. 2009-07-21 11:46:49;339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Outcome measures in palliative care for advanced cancer patients: a review. J Public Health Med. 1997. Jun;19(2):193–9. PubMed . Epub 1997/06/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Quality in health care: QHC. 1999. Dec;8(4):219–27. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2483665. Epub 2000/06/10. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sampson EL, Gould V, Lee D, Blanchard MR. Differences in care received by patients with and without dementia who died during acute hospital admission: a retrospective case note study. Age and ageing. 2006. Mar;35(2):187–9. PubMed . Epub 2006/01/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative Care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002. Aug;24(2):91–6. PubMed . Epub 2002/09/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003. May 14;289(18):2387–92. PubMed . Epub 2003/05/15. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Da Silva RB, Contandriopoulos AP, Pineault R, Tousignant P. A global approach to evaluation of health services utilization: concepts and measures. Healthcare policy = Politiques de sante. 2011. May;6(4):e106–17. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3107120. Epub 2012/05/02. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barbera L, Paszat L, Chartier C. Indicators of poor quality end-of-life cancer care in Ontario. Journal of palliative care. 2006. Spring;22(1):12–7. PubMed . Epub 2006/05/13. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seow H, Barbera L, Howell D, Dy SM. Using more end-of-life homecare services is associated with using fewer acute care services: a population-based cohort study. Medical Care. 2010. Feb;48(2):118–24. PubMed English. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ohta B, Kronenfeld JJ. Intensity of acute care services at the end of life: nonclinical determinants of treatment variation in an older adult population. J Palliat Med. 2011. Jun;14(6):722–8. PubMed English. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emanuel EJ, Young-Xu Y, Levinsky NG, Gazelle G, Saynina O, Ash AS. Chemotherapy use among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2003. Apr 15;138(8):639–43. PubMed . Epub 2003/04/16. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van der Steen JT, Kruse RL, Szafara KL, Mehr DR, van der Wal G, Ribbe MW, et al. Benefits and pitfalls of pooling datasets from comparable observational studies: combining US and Dutch nursing home studies. Palliat Med. 2008. Sep;22(6):750–9. PubMed Epub 2008/08/22. eng. 10.1177/0269216308094102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Earle CC, Ayanian JZ. Looking back from death: the value of retrospective studies of end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2006. Feb 20;24(6):838–40. PubMed . Epub 2006/02/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson AM, Lynn J, Shekelle PG, et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2007. Oct;42(5):1848–70. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2254566. Epub 2007/09/14. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alonso-Babarro A, Astray-Mochales J, Dominguez-Berjon F, Genova-Maleras R, Bruera E, Diaz-Mayordomo A, et al. The association between in-patient death, utilization of hospital resources and availability of palliative home care for cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2013. Jan;27(1):68–75. PubMed English. 10.1177/0269216312442973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alturki A, Gagnon B, Petrecca K, Scott SC, Nadeau L, Mayo N. Patterns of care at end of life for people with primary intracranial tumors: lessons learned. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2014. Mar;117(1):103–15. PubMed Epub 2014/01/29. eng. 10.1007/s11060-014-1360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Au DH, Udris EM, Fihn SD, McDonell MB, Curtis JR. Differences in health care utilization at the end of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and patients with lung cancer. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006. Feb 13;166(3):326–31. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Axelsson B, Christensen SB. Medical care utilization by incurable cancer patients in a Swedish county. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997. Apr;23(2):145–50. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JPW, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A study of the US medicare population. Medical Care. 2007. May;45(5):386–93. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barnato AE, McClellan MB, Kagay CR, Garber AM. Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Health Services Research. 2004. Apr;39(2):363–75. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1361012. English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barnet CS, Arriaga AF, Hepner DL, Correll DJ, Gawande AA, Bader AM. Surgery at the end of life: a pilot study comparing decedents and survivors at a tertiary care center. Anesthesiology. 2013. Oct;119(4):796–801. PubMed English. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829c2db0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bergman J, Chi AC, Litwin MS. Quality of end-of-life care in low-income, uninsured men dying of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2010. May 1;116(9):2126–31. PubMed English. 10.1002/cncr.25039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bergman J, Saigal CS, Lorenz KA, Hanley J, Miller DC, Gore JL, et al. Hospice use and high-intensity care in men dying of prostate cancer. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011. Feb 14;171(3):204–10. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS354602 PMC3286613. English. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Braga S, Miranda A, Fonseca R, Passos-Coelho JL, Fernandes A, Costa JD, et al. The aggressiveness of cancer care in the last three months of life: a retrospective single centre analysis. Psychooncology. 2007. Sep;16(9):863–8. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chan K. Aggressiveness of cancer-care in lung cancer patients near the end-of-life in an oncology center in Hong Kong. Journal of Pain Management. 2012;5(1):71–82. PubMed . English. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cintron A, Hamel MB, Davis RB, Burns RB, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Hospitalization of hospice patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2003. Oct;6(5):757–68. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cooper Z, Rivara FP, Wang J, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Racial disparities in intensity of care at the end-of-life: are trauma patients the same as the rest? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012. May;23(2):857–74. PubMed English. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cowall DE, Yu BW, Heineken SL, Lewis EN, Chaudhry V, Daugherty JM. End-of-life care at a community cancer center. J Oncol Pract. 2012. Jul;8(4):e40–4. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3396828. English. 10.1200/JOP.2011.000451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008. Aug 10;26(23):3860–6. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2654813. English. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Weeks JC, Block SD, et al. Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005. Dec;17(6):505–9. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gielen B, Remacle A, Mertens R. Patterns of health care use and expenditure during the last 6 months of life in Belgium: differences between age categories in cancer and non-cancer patients. Health Policy. 2010. Sep;97(1):53–61. PubMed English. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gonsalves WI, Tashi T, Krishnamurthy J, Davies T, Ortman S, Thota R, et al. Effect of palliative care services on the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in the Veteran's Affairs cancer population. J Palliat Med. 2011. Nov;14(11):1231–5. PubMed English. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodman D, Fisher E, Chang C, Morden N, Jacobson J, Murray K, Miesfeldt S. Quality of end-of-life cancer care for medicare beneficiaries. Regional and hospital specific analyses. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Report.2010; 11162010.dap1.0. Available: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/publications/reports.aspx [PubMed]

- 59.Goodman D, Fisher E, Esty A Chang. Trends and Variation in End-of-Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries with Severe Chronic. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Repor.2011; 04122011.dap1.0. Avaliable: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/publications/reports.aspx [PubMed]

- 60. Goodridge D, Lawson J, Duggleby W, Marciniuk D, Rennie D, Stang M. Health care utilization of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in the last 12 months of life. Respir Med. 2008. Jun;102(6):885–91. PubMed English. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Goodridge D, Lawson J, Rennie D, Marciniuk D. Rural/urban differences in health care utilization and place of death for persons with respiratory illness in the last year of life. Rural Remote Health. 2010. Apr-Jun;10(2):1349 PubMed . English. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012. Feb 1;30(4):394–400. PubMed Epub 2011/12/29. eng. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Henderson J., Goldacre M.J., and Griffith M., Hospital care for the elderly in the final year of life: a population based study. BMJ, 1990. 301(6742): p. 17–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Henderson J, Grimley Evans J, Goldacre MJ. Time spent in hospital by the elderly in the final year of life as a health care indicator: Inter-district comparisons. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1992;14(1):39–42. PubMed . English. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, Lu H, Neville BA, Earle CC. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011. Apr 20;29(12):1587–91. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3082976. English. 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Malin JL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012. Dec 10;30(35):4387–95. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3675701. English. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang CH, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012. May;15(5):548–54. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3353746. English. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, Berke EM, Bynum JP, Murray KM, et al. The care span: End-of-life care for medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Affairs. 2012. April;31(4):786–96. PubMed English. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ramroth H, Specht-Leible N, Konig HH, Brenner H. Hospitalizations during the last months of life of nursing home residents: a retrospective cohort study from Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:70 PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1524759. English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reed SD, Li Y, Dunlap ME, Kraus WE, Samsa GP, Schulman KA, et al. In-hospital resource use and medical costs in the last year of life by mode of death (from the HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial). Am J Cardiol. 2012. Oct 15;110(8):1150–5. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS391869 PMC3462294. English. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA, Murray K, McCabe RJ, Aoun SM, Currow DC. Hospital and emergency department use in the last year of life: a baseline for future modifications to end-of-life care.[Erratum appears in Med J Aust. 2011 Jul 18;195(2):104]. Med J Aust. 2011. Jun 6;194(11):570–3. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sato K, Miyashita M, Morita T, Sanjo M, Shima Y, Uchitomi Y. Quality of end-of-life treatment for cancer patients in general wards and the palliative care unit at a regional cancer center in Japan: a retrospective chart review. Support Care Cancer. 2008. Feb;16(2):113–22. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sheffield KM, Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, Kuo YF, Cooksley CD, Riall TS. End-of-life care in Medicare beneficiaries dying with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011. Nov 1;117(21):5003–12. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS279654PMC3139734. English. 10.1002/cncr.26115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009. Jan;57(1):153–8. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS232087 PMC2948958. English. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, Chen JS, Huang EW, Liu TW. Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009. Sep 20;27(27):4613–8. PubMed . Epub 2009/08/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Temel JS, McCannon J, Greer JA, Jackson VA, Ostler P, Pirl WF, et al. Aggressiveness of care in a prospective cohort of patients with advanced NSCLC. Cancer. 2008. Aug 15;113(4):826–33. PubMed English. 10.1002/cncr.23620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013. Feb 6;309(5):470–7. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3674823. Epub 2013/02/07. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, Whellan DJ, Kaul P, Schulman KA, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011. Feb 14;171(3):196–203. PubMed English. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Warren JL, Barbera L, Bremner KE, Yabroff KR, Hoch JS, Barrett MJ, et al. End-of-life care for lung cancer patients in the United States and Ontario. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011. Jun 8;103(11):853–62. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3115676. English. 10.1093/jnci/djr145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Barbera L, Paszat L, Qiu F. End-of-life care in lung cancer patients in Ontario: aggressiveness of care in the population and a description of hospital admissions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008. Mar;35(3):267–74. PubMed English. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CCH, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Racial variation in end-of-life intensive care use: A race or hospital effect? Health Services Research. 2006. December;41(6):2219–37. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Barnato AE, Chang CC, Farrell MH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Is survival better at hospitals with higher "end-of-life" treatment intensity? Medical Care. 2010. Feb;48(2):125–32. PubMed Pubmed Central PMCID: NIHMS313127 PMC3769939. English. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c161e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Barnato AE, Chang CCH, Saynina O, Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007. March;22(3):338–45. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Keam B, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Kim MR, Im SA, et al. Aggressiveness of cancer-care near the end-of-life in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008. May;38(5):381–6. PubMed English. 10.1093/jjco/hyn031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, Earle CC, Bozeman SR, McNeil BJ. End-of-life care for older cancer patients in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector. Cancer. 2010. Aug 1;116(15):3732–9. PubMed Epub 2010/06/22. eng. 10.1002/cncr.25077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Richardson SS, Sullivan G, Hill A, Yu W. Use of aggressive medical treatments near the end of life: differences between patients with and without dementia. Health Services Research. 2007. Feb;42(1 Pt 1):183–200. PubMed . Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1955744. English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bukki J, Scherbel J, Stiel S, Klein C, Meidenbauer N, Ostgathe C. Palliative care needs, symptoms, and treatment intensity along the disease trajectory in medical oncology outpatients: a retrospective chart review. Support Care Cancer. 2013. Jun;21(6):1743–50. PubMed Epub 2013/01/25. eng. 10.1007/s00520-013-1721-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. O'Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Tamura MK. Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA—Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010. 14 Jul;304(2):180–6. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Giovanis P, De Leonardis G, Garna A, Lovat V, Caldart F, Quarta A, et al. Clinical governance benchmarking issues in oncology: aggressiveness of cancer care and consumption of strong opioids. A single-center experience on measurement of quality of care. Tumori. 2010. May-Jun;96(3):443–7. PubMed . English. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Toole M, Lutz S, Johnstone PAS. Radiation oncology quality: Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. JACR Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2012. March;9(3):199–202. PubMed English. 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.