Abstract

The interpersonal theory of suicide proposes that severe suicidal ideation is caused by the combination of thwarted belongingness (TB) and perceived burdensomeness (PB), yet few studies have actually examined their interaction. Further, no studies have examined this proposal in male prisoners, a particularly at-risk group. To address this gap, the current study surveyed 399 male prisoners. TB and PB interacted to predict suicidal ideation while controlling for depression and hopelessness. High levels of both TB and PB were associated with more severe suicidal ideation. The interpersonal theory may aid in the detection, prevention, and treatment of suicide risk in prisoners.

Keywords: Suicide ideation, Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, Thwarted Belongingness, Perceived Burdensomeness, Male Prisoners

Suicide is a leading cause of death is US prisons (Mumola, 2005). As in the general population, male prisoners are at significantly greater risk for suicide compared to women (Fazel, Grann, Kling, & Hawton, 2011). Suicide prevention efforts in prisons are hindered by many of the same obstacles of those in the general population. Barriers to suicide risk assessment and prevention include underreporting of suicide ideation and behaviors, stigma associated with disclosing suicidal thoughts and/or risk factors for suicide (e.g., depression), perceptions that prisoners are being manipulative, and imprecise risk assessment frameworks. Imprecise risk assessment frameworks typically have the quality of being overly sensitive and poorly specific due to the low base rate of suicide (Pokorny, 1983). Although highly sensitive predictors of risk may be preferred when dealing with potentially suicidal prisoners, limitations in emergency services and the potential for iatrogenic effects of solitary confinement indicate that new ways of conceptualizing suicide risk are required.

The current poor specificity in the estimation of suicide risk is also influenced by the manner in which suicide is studied. Research studies examining suicide have typically examined distal risk factors. Depression and hopelessness, for example, are of the strongest predictors of suicide risk, but have predominantly been studied over protracted periods of time (Nock et al., 2008). Methodological limitations preclude our ability to examine the temporal context in which suicide is most likely to occur. As such, suicide risk assessment is predicated heavily on distal risk factors for suicide (Conwell, Van Orden, & Caine, 2011). Alternatively, were we to obtain a better understanding of acute risk factors or more proximal antecedents to suicide, better and more precise risk assessment frameworks would be feasible.

In the absence of data examining proximal antecedents to suicide, researchers have turned to comprehensive theories to better understand the development of acute suicide risk. Theory allows providers to understand and contextualize the interaction of dynamic risk and protective factors in order to better assess risk for suicide and identify critical points of intervention. In other words, theory takes us from questions about what things are associated with suicide to questions about why people die by suicide.

The interpersonal theory of suicide has left an indelible impression on the research and clinical fields of suicide prevention since its initial articulation (Joiner, 2005). The main assumption of the interpersonal theory is that an individual is at risk for death by suicide when, and only when, he experiences both the capability and desire for suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). According to the interpersonal theory, the acquired capability for suicide is a condition of fearlessness of death and the capacity to tolerate physical pain such that self-preservation mechanisms no longer prevent an individual from suicide (Smith & Cukrowicz, 2010). Joiner and colleagues (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) suggest that far fewer individuals are capable of suicide compared to the number of those who experience suicidal desire.

Though the notion of an acquired capability for suicide is one of its more novel features relative to previous theories of suicide, the interpersonal theory also postulates specific falsifiable hypotheses regarding the causes of passive suicide ideation, suicidal desire, suicidal intent, and lethal (or near-lethal) suicide attempts. Such hypotheses, if supported by a large body of empirical literature, would advance our ability to develop more focused and targeted suicide risk assessment, prevention, and intervention programs.

According to the interpersonal theory, suicidal desire is most proximally caused by the interaction of two psychological states: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Van Orden et al., 2010). Thwarted belongingness is a subjective feeling state in which the basic need for affiliation goes unmet: that one does not experience close relationships that involve reciprocal care and concern. Perceived burdensomeness involves the belief that one is a liability to others due to his incompetence in living. Although the experience of each of these states individually may result in passive suicidal ideation and/or morbid ruminations, the interpersonal theory contends that it is the combination of and hopelessness regarding the two that result in the most severe and potentially active form of suicidal ideation.

Research examining the role of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in the development of suicide ideation has generally been supportive. Several studies have demonstrated that perceived burdensomeness and/or thwarted belongingness are independently associated with suicide ideation across a number of different populations including elder adults in primary care (e.g., Jahn, Cukrowicz, Linton, & Prabhu, 2011), military service members (e.g., Bryan, Clemans, & Hernandez, 2012), undergraduate students (e.g., Britton, Van Orden, Hirsch, & Williams, 2014), and mental health outpatients (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2011). Themes of perceived burdensomeness have also been detected in the content of notes left by suicide decedents (Joiner et al., 2002). This growing literature supports the notion that experiences of thwarted belongingness or perceive burdensomeness independently influence suicide ideation. However, there exist only a handful of studies that have the relationships of thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness with suicide ideation in a manner consistent with the most severe and pernicious form of suicide ideation: the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness.

To date, only five studies, to our knowledge, have examined the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness in the prediction of suicide ideation. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness interacted to predict suicide ideation in African American undergraduate students (Davidson, Wingate, Slish, & Rasmussen, 2010), clinical outpatients (Joiner et al., 2009), and community dwelling adults (Christensen, Batterham, Soubelet, & Mackinnon, 2012). Kleiman, Liu, and Riskand (2014) found that a unitary latent factor including both thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness predicted suicide ideation using a prospective design. Further, consistent with the assertion that other distal factors influence suicide risk via their impact on thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness (Van Orden et al., 2010), the influence of depression on suicide ideation was found to occur indirectly via this unified interpersonal factor (Kleiman et al., 2014).

The current study aimed to test a critical hypothesis of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a sample of male prisoners. The current study is novel in two respects. First, the current study expands the populations in which thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness have been examined to male prisoners. Second, it is one of only a handful of studies to examine the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in relation to suicide ideation. Such studies are critical to attempting to falsify the postulates set forth by the theory and, by consequence, determining its suitability for serving as a keystone in the development of clinical programming. We hypothesized that self-reported experiences of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would independently predict suicide ideation while also controlling for depression and hopelessness. We also hypothesized that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would interact to predict current suicide ideation while controlling for depression and hopelessness. Those participants who endorsed the highest levels of both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were expected to report the most severe suicidal ideation.

Methods

Participants

The sample for the present study consisted of 399 adult male prison inmates incarcerated within the Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC). The majority (i.e., approximately 95%) of the participants were recruited from a large “state prison,” whereas the remaining approximate 5% were recruited from a regional facility that houses both prison and jail inmates. Participants’ mean age was 34.94 years (sd=10.86, range=19–69). Slightly over half (55.1%) of the participants identified as Black or African American, 36.1% identified as White or Caucasian, with the remaining 5% identifying as another race/ethnicity (e.g., Native American, Asian, Hispanic/Latino). Regarding highest level of educational attainment, slightly over half (55.2%) of the participants reported having earned a high school diploma or GED, 18.0% reported educational attainment below a high school diploma or GED (e.g., some grade school, no formal education), and 26.8% reported attainment above a high school diploma or GED (e.g., some college, college degree, advanced degree). Participants’ mean sentence length was 9.11 years (sd=9.33, range=3 months to 60 years), with a mean time served on their current sentence of 3.97 years (sd=5.28, range=less than one month to 31 years). A small portion (i.e., 8.0%) of the sample were serving life sentences.

Materials

Demographic Form

A demographic form was created by the researchers specifically for the purposes gathering self-reported information regarding the composition of the sample of participants (e.g., age, race, sentence length).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ)

The INQ (Van Orden et al., 2011) is a 15 item self-report measure of Perceived Burdensomeness (INQ-PB, 6 items) and Thwarted Belongingness (INQ-TB, 9 items). Respondents indicate the degree to which statements are true for them on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=Not at all true for me, 7=Very true for me). Higher scores represent higher levels of the respective constructs. The INQ has shown evidence of convergent, divergent, and criterion validity (Van Orden et al., 2011). Internal consistencies of the INQ scales in the current study were good (INQ-TB α=.76, INQ-PB α=87).

Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS)

The BSS (Beck & Steer, 1993) is a 21-item self-report measure of the presence and severity of suicidal ideation, wishes, and attitudes. Respondents indicate which one of three statements best reflects their experience over the past week. Responses are scored as 0, 1, or 2, and scores are summed for a total scale in which higher scores indicate more severe suicide ideation. Internal consistency of the BSS in the current study was excellent (α=.94).

Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CESD)

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item self report measure of depressive symptoms. The CES-D has shown to be a reliable and valid instrument in a multitude of populations (Beeber, Shea, & McCorkle, 1998; Kim, DeCoster, Huang, & Chiriboga, 2011; Poresky, Clark, & Daniels, 2000; Ricarte et al., 2011). Internal consistency of the CES-D in the present study was good (α=.86)

Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide Screening Form – Hopelessness scale (DHS-H)

The DHS-H is a10-item self-report scale that was selected from the DHS (Mills & Kroner, 2004). The DHS-H consists of statements indicating a negative outlook about one’s future. Respondents indicate whether each statement is “true” or “false” for them. Higher scores DHS-H represent a sense of being inundated with life and a pessimistic outlook towards the future. The DHS has been established as a reliable and valid instrument in both offender and non-offender samples (Mills & Kroner, 2004, 2005). Internal consistency of the DHS-H in the present study was good (α=.86)

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Southern Mississippi and MDOC. All English-literate prison inmates housed in the general population of each institution were considered appropriate for participation in the study (i.e., those housed in segregation were excluded from participation). Potential participants were identified by MDOC officials using a convenience approach in order to maintain the safe and efficient functioning of the institution. Potential participants were provided a verbal description of the study and an opportunity to ask questions before deciding to participate. Participants who declined to participate were allowed to return to their regular activities. Participants who agreed to participate in the study provided written informed consent. Study surveys were presented in paper-and-pencil form in a counterbalanced fashion to control for order effects.

Results

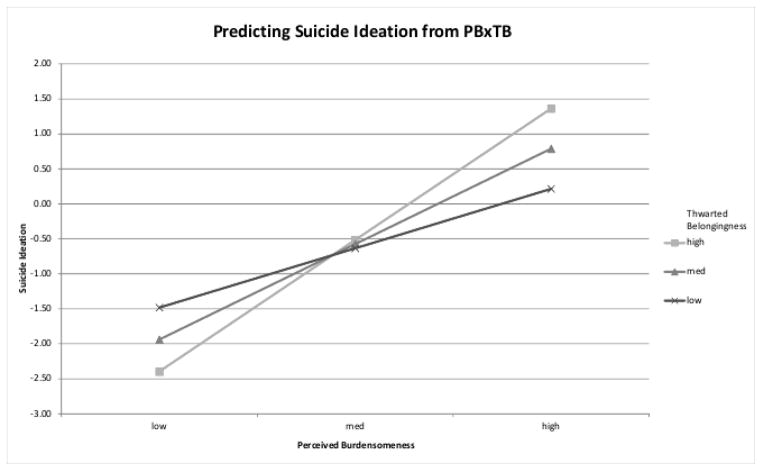

In the current sample the CESD mean was 20.57 (sd=11.45), the BSS mean was 2.22 (sd=5.30), and the DHS-H mean was 2.23 (sd=2.64). In order to examine the hypothesis that the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness predict suicide ideation, we conducted a hierarchical multiple linear regression (MLR) with BSS scores as the criterion variable. The CESD and DHS-H were entered in step 1, the INQ-TB and INQ-PB were entered in step 2, and the interaction term of the INQ-TB and INQ-PB was entered in step 3. Predictors were mean centered as recommended by Aiken and West (1991). A summary of the MLR is presented in Table 1. The overall MLR was significant R2=.34, F(5,386)=41.202, p<.001. Depression (β=.274, t=5.518, p<.001) and hopelessness (β=.312, t=5.906, p<.001) contributed significantly to the prediction of suicide ideation. The main effect of perceived burdensomeness (β=.312, t=6.102, p<.001), but not thwarted belongingness (β=.003, t=.056, p=.955), predicted suicide ideation while also controlling for depression and hopelessness. This main effect was qualified by the significant interaction of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (β=.113, t=2.431, p=.016). Simple slopes of perceived burdensomeness prediction of suicide ideation were calculated using trichotomized levels of thwarted belongingness. Although perceived burdensomeness was positively associated with suicide ideation at each level of thwarted belongingness, the relationship between perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation was strongest for those expressing high thwarted belongingness (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Hierarchical Linear Regression Predicting Suicide Ideation

| Predictor | ΔF (p) | ΔR2 | b | β | t (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | 72.325 (<.001) | .271 | |||

| CES-D | .125 | .274 | 5.185 (<.001) | ||

| DHS-H | .606 | .312 | 5.906 (<.001) | ||

| Block 2 | 19.568 (<.001) | .067 | |||

| CES-D | .079 | .174 | 3.264 (.001) | ||

| DHS-H | .413 | .213 | 3.890 (<.001) | ||

| INQ-PB | .186 | .312 | 6.102 (<.001) | ||

| INQ-TB | .001 | .003 | .056 (.955) | ||

| Block 3 | 5.908 (.016) | .010 | |||

| CES-D | .083 | .184 | 3.458 (.001) | ||

| DHS-H | .382 | .197 | 3.592 (<.001) | ||

| INQ-PB | .156 | .262 | 4.763 (<.001) | ||

| INQ-TB | .005 | .011 | .226 (.821) | ||

| INQ-PBxINQ-TB | .005 | .113 | 2.431 (.016) |

Note. DHS-H: Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide Screening Form-Hopelessness Scale; CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; INQ-TB: Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-Thwarted Belongingness Scale; INQ-PB: INQ-Perceived Burdensomeness.

Table 2.

Simple Slopes for Interaction of Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness in the Prediction of Suicidal Ideation

| Simple Slope | Standard Error | 95% CI | t(p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High TB | .215 | .032 | .155–.275 | 6.80 (<.001) |

| Medium TB | .156 | .032 | .096–.216 | 4.94 (<.001) |

| Low TB | .097 | .047 | .007–.187 | 2.06 (.040) |

Note. TB was trichotomized such that Low consisted of the lowest third of the TB score, Medium consisted of the middle third of the TB score, and High consisted of the highest third of the TB scores.

Figure 1.

Simple Slopes for Interaction of Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness in the Prediction of Suicidal Ideation. TB=Thwarted Belongingness, PB=Perceived Burdensomeness.

Discussion

The current study examined the relations of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness within a sample of adult male prisoners. The current study is novel in two ways: it is the first study that we are aware of to examine the relations of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in male prisoners and it is one of only a few studies to examine the interaction of these variables in relation to suicide ideation. Consistent with our hypothesis, suicide ideation was strongest among those who reported higher levels of both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. This interaction was significant while also controlling for depression and hopelessness.

It has been suggested that each individual suicide is so multiply and idiosyncratically determined that a universal causal mechanism is not feasible (Maris, Berman, Silverman, & Bongar, 2000). The interpersonal theory of suicide is ambitious in that it proposes such a specific mechanism by which suicide ideation is caused. Consistent with the current findings, the interpersonal theory contends that risk factors such as depression and hopelessness can facilitate suicidal thinking, but it is the combination of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness that will result in the most severe and pernicious form of suicidal ideation. Furthermore, the theory suggests that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness do not create depressed mood and hopelessness about the future, which then promotes suicidal ideation. The current findings support this aspect of the interpersonal theory.

The present study not only bolsters support for the interpersonal theory, it also expands its applicability to a population in which the interpersonal components may be especially relevant. Incarcerated individuals are likely at elevated risk for thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Incarceration, by its very nature, thwarts belongingness by causing physical isolation from established social support systems, and loneliness has been shown to be related to suicide risk for offenders (Brown & Day, 2008). The effect of incarceration on perceived burdensomeness seems even more apparent. Incarceration creates a significant cost to society in general and to offenders’ family and friends, which may promote perceived burdensomeness. The costs to family and friends may include no longer providing income, child-care, and household maintenance. Further, incarceration may place burdens on others, including legal costs, giving money to the inmate for commissary purchases, and the inconvenience of traveling to visit the offender.

Incarceration likely promotes thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, so it is unsurprising that the prevalence of suicidal ideation reported in our sample (33%) was higher than in the US general population (i.e., 2–10%; Nock et al., 2008). Given that nearly a third of those who experience suicide ideation at some point attempt suicide (Nock et al., 2008), the high rate of suicide ideation amongst offenders requires the attention of correctional mental health providers. Specifically, improving detection of suicidal ideation among incarcerated offenders is imperative. Prisoners, however, may avoid reporting suicide ideation for fear of stigmatization, being perceived as weak by peers, or negative outcomes (e.g., transfer to psychiatric housing, placement under suicide monitoring).

Detecting important indicators of suicide ideation, namely thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, may improve detection of at-risk inmates. These experiences could be evaluated in inmates already receiving psychological services, or in the general prison population via self-report measures to detect at-risk inmates who are “off the radar.” Although correctional mental health providers may realize benefits of assessing for thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in these ways, all correctional staff should be educated about these interpersonal risk factors. In doing so, officers, nurses, administrators, etc. may become aware of indicators that an inmate is at risk for suicide ideation. For example, correctional staff may focus on factors such as an inmate’s visitation rights being revoked, transfer away from family and/or friends in the community, or ostracization by their in-prison in-group.

Correctional mental health providers can also implement the themes of the interpersonal theory in treatment with those who report experiencing suicide ideation. Although it is sometimes necessary to place high-risk inmates in “suicide watch” cells to continuously monitor their behavior, consideration of how isolation diminishes belongingness is important. Inmates who experience suicide ideation may benefit from treatment that focuses on bolstering belongingness and reducing perceived burdensomeness. To increase belongingness, treatment goals may include fostering beneficial relationships with family and friends in the community as well as promoting prosocial affiliations with fellow inmates (e.g., through classes, groups, and programs). To reduce perceived burdensomeness, treatment may target unrealistically negative beliefs an inmate has about their impact on others. Treatment providers may also help inmates reduce their actual burden on others by, for example, working towards obtaining a transfer closer to family and friends in the community or lessening their financial reliance on family and friends.

Despite the importance of our findings, the current study had limitations. We used a cross-sectional design that prohibits causal inference and prediction of suicide ideation development. In addition, all data were collected via self-report measures. Although research suggests that inmates accurately report demographic and incarceration-related information (Kroner, Mills, & Morgan, 2007), participants in our study may have presented their experiences and behavior overly positively, particularly in relation to suicide ideation, for fear of negative consequences despite the anonymous nature of the study. Lastly, the current study utilized convenience sampling to minimize interference on prison operations. Thus, the participants were not likely experiencing a severe suicidal crisis. It is possible that relationships among the purported causes of suicidal ideation may change as a function of psychological state; they may be context-specific and/or non-linear over time. Arguably, the most relevant instance in which to examine the purported causes of suicidal ideation is during an acute suicidal crisis.

The present study was the first, to our knowledge, to examine the relations of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness with suicidal ideation in male prisoners. Further, the current study is one of only a few to examine how the interaction of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness is associated with suicidal ideation. The interpersonal theory has gained a strong, and growing basis of empirical support since its articulation almost 10 years ago. However, more work is required to substantiate its position as a basis for clinical intervention and prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (YIG-0-10-293) and the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH020061).

Contributor Information

Jon T. Mandracchia, University of Southern Mississippi.

Phillip N. Smith, University of South Alabama.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beeber LS, Shea J, McCorkle R. The Center for Epidemiologie Studies Depression Scale as a measure of depressive symptoms in newly diagnosed patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1998;16:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Britton PC, Van Orden KA, Hirsch JK, Williams GC. Basic psychological needs, suicidal ideation, and risk for suicidal behavior in young adults. Suicide and Life- Threatening Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Day A. The role of loneliness in prison suicide prevention and management. Journal of offender rehabilitation. 2008;47:433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM. Perceived burdensomeness, fearlessness of death, and suicidality among deployed military personnel. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52:374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Soubelet A, Mackinnon AJ. A test of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in a large community-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;44:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34:451–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Slish ML, Rasmussen KA. The great black hope: Hope and its relation to suicide risk among African Americans. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:170–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.2.170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Grann M, Kling B, Hawton K. Prison suicide in 12 countries: an ecological study of 861 suicides during 2003–2007. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46:191–195. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC, Linton K, Prabhu F. The mediating effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relation between depressive symptoms and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2011;15:214–220. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pettit JW, Walker RL, Voelz ZR, Cruz J, Rudd MD, Lester D. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: Two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, Rudd MD. Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2009;118:634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, DeCoster J, Huang C, Chiriboga DA. Race/ethnicity and the factor structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: A meta-analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:381–396. doi: 10.1037/a0025434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Liu RT, Riskind JH. Integrating the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide into the depression/suicidal ideation relationship: a short-term prospective study. Behavior Therarpy. 2014;45:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner DG, Mills JF, Morgan RD. Underreporting of crime-related content and the prediction of criminal recidivism among violent offenders. Psychological Services. 2007;4:85–95. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.4.2.85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maris RW, Berman AL, Silverman MM, Bongar BM. Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mills JF, Kroner DG. A New Instrument to Screen for Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide in Incarcerated Offenders. Psychological Services. 2004;1:83–91. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.1.1.83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JF, Kroner DG. Screening for suicide risk factors in prison inmates: Evaluating the efficiency of the Depression, Hopelessness and Suicide Screening Form (DHS) Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2005;10:1–12. doi: 10.1348/135532504X15295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ. Suicide and Homicide in State Prisons and Local Jails. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/Epirev/Mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients: Report of a prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:249–257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790030019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poresky RH, Clark K, Daniels AM. Longitudinal characteristics of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-depression scale. Psychological Reports. 2000;86:819–826. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.86.3.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricarte JJ, Navarro B, Serrano JP, Aguilar MJ, Latorre JM, Ros L. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations with and without cognitive impairment. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2011;72:83–110. doi: 10.2190/AG.72.2.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PN, Cukrowicz KC. Capable of suicide: a functional model of the acquired capability component of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:266–275. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24:197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]