Abstract

A significant proportion of autoimmune-associated genetic variants are expressed in B cells, suggesting that B cells may play multiple roles in autoimmune pathogenesis. In this review, we highlight recent studies demonstrating that even modest alterations in B cell signaling are sufficient to promote autoimmunity. First, we describe several examples of genetic variations promoting B cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmune germinal centers and autoantibody production. We highlight how dual antigen receptor/toll-like receptor signals greatly facilitate this process and how activated, self-reactive B cells may function as antigen presenting cells, leading to loss of T cell tolerance. Further, we propose that B cell-derived cytokines may initiate and/or sustain autoimmune germinal centers, likely also contributing, in parallel, to programing of self-reactive T cells.

Introduction

The importance of B cells in the pathogenesis of human autoimmunity is well established. Specific autoantibody profiles serve as serologic hallmarks of multiple autoimmune diseases, and B cell directed therapies have demonstrated therapeutic benefit in clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1], type 1 diabetes (T1D) [2], ANCA vasculitis [3], multiple sclerosis (MS) [4], and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [5]. Notably, B cell targeted therapies frequently provide lasting clinical benefit without significantly impacting autoantibody levels, suggesting that other B cell functions, including antigen presentation and cytokine production, play important roles in autoimmune pathogenesis.

While the mechanisms promoting B cell activation during autoimmunity have not been completely defined, multiple genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of human autoimmune disease risk have implicated genetic polymorphisms that impact lymphocyte activation responses [6-8]. In this context, it is known that even modest alterations in B lymphocyte signaling thresholds can promote autoimmunity in the appropriate environmental setting [9]. Based on emerging data, we propose a model wherein altered B cell signals are sufficient to promote spontaneous activation of self-reactive B cell clones via self-antigen, allowing B cells to function as antigen presenting cells that trigger a loss in T cell tolerance and facilitate spontaneous germinal center (GC) reactions that promote development of high-affinity, class-switched autoantibodies.

The importance of dysregulated GC responses in autoimmunity is reinforced by the observation that anti-dsDNA (and RNA-associated) autoantibodies cloned from SLE patients are typically class-switched and somatically hypermutated [10]. Similarly, high-affinity anti-insulin and islet-specific antibodies are present in the majority of pre-diabetics, including very young subjects. Although B cells can also undergo somatic hypermutation at extrafollicular sites in murine autoimmune models [11], spontaneous GCs are frequently observed in B cell-driven murine models and in human autoimmune patients, implicating antigen-driven, GC selection in autoantibody production [12]. Tertiary lymphoid follicles and ectopic GCs have also been demonstrated within inflamed RA joints, lupus nephritis kidneys and meninges in MS, further reinforcing the importance of B:T cross-talk in the pathogenesis of systemic autoimmunity [13].

B cells express both clonally-rearranged antigen receptors (BCR) and innate pattern-recognition receptors (including toll-like receptors, TLRs), and have a unique propensity for activation via integrated signaling through these pathways [14]. Robust anti-viral antibody responses are dependent on B cell-intrinsic TLR signals via the adaptor protein MyD88, emphasizing the evolutionary advantage of this arrangement [15]. However, dual BCR/TLR activation also increases the risk of autoimmunity, since B cell TLRs can also respond to endogenous ligands [14,16,17]. Because dual BCR/TLR activation serves protective functions during infection, and also carries the potential to promote autoimmunity, these signaling pathways must be tightly regulated.

In this review, we describe recent animal studies in which genetic manipulation of B cell signaling has been shown to promote T cell activation, spontaneous GC responses and systemic autoimmunity. In particular, we will focus on genetic changes that exert both a B cell-intrinsic impact on autoimmunity, and have direct relevance to our understanding of how human candidate risk variants may promote disease.

Dysregulated B cell signals promote spontaneous autoimmunity

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

In addition to recurrent infections, eczema and bleeding diathesis, patients with the primary immunodeficiency disorder, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), experience high rates of humoral autoimmunity [18]. In contrast to marked attenuation of T cell receptor signaling, WAS protein (WASp)-deficient B cells are modestly hyper-responsive to both BCR and TLR ligands [19]. To model the impact of this dysregulated signaling on autoimmunity risk, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras in which B cells, but not other cellular lineages, lack WASp. Strikingly, hyper-responsive was−/− B cells were sufficient to promote wild-type CD4+ T cell activation and spontaneous GCs, resulting in class-switched autoantibody production and immune-complex glomerulonephritis. Further, B cell-intrinsic MyD88 deletion abrogated CD4+ T cell activation and spontaneous GC formation [19]. Together with other murine models showing a similar role for B cell MyD88 signals in disease pathogenesis [20,21,22•,23•], this observation emphasized the critical importance of dual BCR/TLR-activation in driving autoimmunity and lends support to our model whereby autoreactive B cells directly promote CD4+ T cell responses.

We recently utilized the was−/− chimera model to further dissect the B cell-intrinsic signals responsible for spontaneous autoimmunity. The MyD88-dependent receptors TLR7 and TLR9 have long been known to be required for anti-nuclear antibody production. In murine lupus models, global deletion of TLR7 abolishes autoantibodies to RNA-associated proteins and limits systemic autoimmunity, while TLR9 deletion prevents anti-dsDNA and anti-chromatin antibodies but exacerbates disease [24-27]. Whether B cell or myeloid TLR signals explain these opposing phenotypes had not been addressed. For this reason, we directly tested the impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 vs TLR9 deletion in the was−/− chimera model. B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 deletion exert opposing impacts on the generation of RNA- and DNA-associated autoantibodies, respectively. In addition, B cell TLR7 deletion prevented, while TLR9 deletion exacerbated, systemic autoimmunity, recapitulating the phenotype of global TLR7- and TLR9-deficient lupus strains [28•].

This study emphasized the critical importance of B cell TLR7 signaling in the pathogenesis of murine lupus. The importance of TLR7 is additionally shown using models in which TLR7 is overexpressed, including male mice with the spontaneous Yaa translocation or TLR7-transgenic (TLR7-Tg) animals [29]. Although enhanced TLR7 signals likely impact several immune lineages, TLR7-Tg B cells are preferentially recruited into spontaneous GCs in competitive chimeras suggesting that B cell-intrinsic TLR7 signals preferentially drive autoimmune GCs [30]. Interestingly, B cell TLR7 signals were also shown to promote, and TLR9 to limit, the development of low-level spontaneous GCs in non-autoimmune C57BL/6 mice housed within specific pathogen free environments. Further, this process relies upon B cell intrinsic TLR signaling and is not impacted by myeloid specific loss of MyD88 [31•]. Finally, over-expression of soluble RNAse ameliorated autoimmunity in TLR7 transgenic mice, implicating endogenous RNA in disease pathogenesis and suggesting a possible therapeutic strategy in SLE [32].

In human genetic studies, SNPs within TLR7 have only been associated with SLE in a small subset of patients [33-35]. However, polymorphisms genes encoding proteins and transcription factors downstream of TLR activation, including TNFAIP3, TNIP1 and IRF5, correlate with lupus risk [36,37]. Further, variants in SLC15A4, a histidine transporter involved in lysosomal TLR signaling, are associated with SLE [36]; and B cell-intrinsic SLC15A4 deletion limits autoimmunity in murine models [38]. With the exception of SLC15A4, whether these GWAS signaling variants impact B cells vs. other immune lineages during disease pathogenesis remains to be determined. However, the murine studies described above support a model whereby dysregulated TLR (in particular TLR7) signaling, together with altered BCR signals, is sufficient to promote B cell activation and autoantibody production in the appropriate environmental context.

LYN deficiency

Deficiency of the Src family tyrosine kinase, Lyn, results in spontaneous autoimmunity characterized by splenomegaly, anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and glomerulonephritis [39]. In B cells, Lyn promotes proximal BCR signaling but also inhibits B cell activation by phosphorylating immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs on CD22, a sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin (Siglec), and the inhibitory FC-receptor FcγRIIB. Consistent with this, BCR-mediated calcium flux is enhanced in Lyn−/− B cells [40].

To address whether B cell-intrinsic deletion of Lyn is sufficient for development of autoimmunity, Lamagna et al. utilized a Cre-recombinase strategy to delete Lyn specifically in B cells [41•]. B cell-intrinsic Lyn deficiency promoted development of class-switched autoantibodies to dsDNA and RNA-associated antigens, as well as splenic immune activation and immune-complex glomerulonephritis. Although total numbers of GC B cells were not increased (likely secondary to the B cell lymphopenia in this model), IgD−FAS+GL7+GC B cells as a percentage of CD19+ cells appear expanded in CD79acre-lynfl/fl mice. Consistent with this interpretation, deletion of the SAP adaptor protein required for interaction between T follicular helper cells (TFH) and GC B cells markedly decreased anti-dsDNA Ab in Lyn−/− mice, implicating GCs in the genesis of autoantibodies in this model [23•].

Deletion of the signaling adaptor MyD88, either globally [41•] or only in B cells [23•], prevented activation of Lyn−/− B cells, class-switched antibody formation and systemic autoimmunity. Similar to the was−/− chimera model, this suggests that, by enhancing BCR signaling, Lyn deletion promotes B cell activation via dual BCR and TLR signals.

In addition to these murine data, SNPs in Lyn and a related Src family kinase BLK are associated with human lupus risk [42-44]. Further, rare loss-of-function mutations in sialic acid acetyl esterase (SIAE ), which is required for function of the inhibitory siglec, CD22, markedly increase the risk of RA, T1D and SLE [45]. These data implicate the SIAE, CD22, Lyn inhibitory axis in regulating B cell activation and the prevention of humoral autoimmunity.

PTPN22

Protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor 22 (PTPN22), encodes the tyrosine phosphatase, LYP, that negatively regulates lymphocyte activation downstream of both the BCR and T cell antigen receptor (TCR). Population-based studies have demonstrated that a 1858C→T single-nucleotide polymorphism in PTPN22 (resulting in R620W amino acid substitution in LYP) is associated with susceptibility to multiple humoral autoimmune diseases including SLE [6], T1D [7], and RA [46]. Prior studies have reported contradictory findings as to whether the PTPN22 variant serves as a gain- or loss-of-function allele. Further, whether LYP R620W predisposes to autoimmunity primarily via impacting T vs. B cell function had not been addressed.

To address these questions, two groups, including our own [47••,48••] independently generated murine knock-in models containing the equivalent amino acid change, R619W, in the murine orthologue protein PEST domain phosphatase, PEP. T and B cells from knock-in mice exhibited enhanced antigen receptor signaling, expansion of memory/effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and spontaneous GCs in aged mice. While significant autoimmunity was not observed in knock-in mice on the C57BL/6 background [48••], aged knock-in mice on a mixed C57BL/6J and 129/Sv genetic background developed autoimmune disease characterized by a broad range of autoantibodies, vasculitis and immune complex renal injury [47••].

Since the PTPN22 variant impacts both T and B cell activation, we tested whether B cell-intrinsic expression of PEP R619W might be sufficient to induce autoimmunity. We utilized an alternative model wherein the murine variant is expressed via the Rosa-26 promoter specifically within B cells [47••]. Strikingly, aged mice developed splenomegaly with spontaneous GCs, anti-dsDNA autoantibodies, and glomerulonephritis. Finally, B cell intrinsic MyD88 deficiency abrogates spontaneous GCs and autoantibody production mediated by variant expressing B cells (X Dai, DJ Rawlings; unpublished data). Taken together, these findings indicate that dysregulated PTPN22-dependent signals are sufficient to promote systemic autoimmunity in a B cell-intrinsic manner.

BANK1

The B cell scaffolding protein, BANK1, binds Src family protein tyrosine kinases and promotes BCR-mediated calcium flux via Lyn-mediated phosphorylation of the inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) in B cell lines [49]. In contrast, while Bank−/− primary B cells display normal BCR triggered calcium flux, Bank−/− mice exhibit enhanced T-dependent antibody responses and GC formation. In vitro , Bank-deficiency results in enhanced CD40-mediated proliferation, survival and Akt activation, implying a key role in regulating B cell responses to T cell help [50].

In humans, two nonsynonymous variants in BANK1 , leading to Arg61His and Ala383Thr substitutions, are highly associated with SLE susceptibility [51]. While the relationship between these variants and disease pathogenesis has not been determined, the increase in CD40 mediated Akt signals in Bank1 deficiency suggests that BANK1 variants may promote autoimmunity via modulation of B:T interactions within autoimmune GCs.

B cell antigen presentation in autoimmunity

In addition to producing antibodies, B cells process antigens and present them to CD4+ T cells as peptide fragments in the context of MHC Class II. As described above, dysregulated B cell signaling may be sufficient to promote CD4+ T cell activation and expansion, suggesting a role for B cell antigen presentation in promoting initial breaks in T cell tolerance during humoral autoimmunity. Direct evidence for B cell antigen-presenting cell (APC) function driving autoimmunity is limited to a few murine studies. For example, in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, B cells expressing surface, but not secreted, IgM develop penetrant diabetes despite absence of islet autoantibodies [52]. In addition, B cell-intrinsic deletion of MHC Class II I-Ag7 prevents CD4+ T cell activation and T1D in the NOD background [53]. Skewing the BCR repertoire towards insulin reactivity also accelerates diabetes, despite lack of antibody production by BCR heavy chain transgenic strains, further implicating B cell APC function in diabetes pathogenesis [54].

Similar findings were recently documented in the experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) model of multiple sclerosis, when Molnarfi and colleagues elegantly dissected the impact of B cell APC function vs. antibody production on disease progression. Transgenic mice expressing a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-specific BCR developed acute EAE, even though these B cells were engineered to be unable to secrete antibody. In contrast, mice with MHC Class II-deficient B cells failed to develop pro-inflammatory TH1 and TH17 cells and were resistant to EAE induced by immunization with full-length MOG [55•].

Together, these studies highlight an important role for B cell antigen presentation in promoting T cell activation in autoimmunity. Although not yet addressed, we predict that activated effector/memory CD4+ T cells in the B cell-driven murine lupus models described above, likely target self-epitopes derived from nuclear autoantigens. Confirming this hypothesis will lend further support to the model whereby activated autoreactive B cells initiate breaks in T cell tolerance.

B cell cytokines in autoimmune GC responses

B cells can also produce cytokines, suggesting another mechanism whereby B cells can impact autoimmune pathogenesis. On the basis of cytokine profiles, B cells have traditionally been divided into effector and regulatory subsets. Effector B cells were originally designated as IFN-γ/IL-12 (“B effector 1”) and IL-2/IL-4/IL-6 (“B effector 2”) subsets. In contrast, B cells can suppress immune responses via the production of IL-10 and TGFβ [56]. Recently, we demonstrated that B cells can produce IL-17 during Trypanosoma cruzi infection [57•], and Fillatreau’s group showed B cells to be a primary source of immunosuppressive IL-35 [58•,59]. These recent findings expanded the mechanisms whereby B cells regulate both infectious and autoimmune models. An important caveat is that effector and regulatory B cell subsets may exhibit significant plasticity depending on environmental and inflammatory context. In addition, unlike effector and regulatory T cells subsets, cytokine-producing B cells have not been shown to fulfill the requirements of classic immune lineages, such as defining transcription factors.

There is broadening evidence that key cytokines markedly influence GC biology, including dysregulated GCs in the setting of autoimmunity. In this context, cytokines promote the generation and accumulation of T follicular helper cells (TFH), regulate B cell activation, survival and class-switch recombination and similar events presumably coordinate formation and outcome of ectopic GCs in autoimmunity [60].

Whether B cell cytokines directly impact GC responses, however, has been less extensively addressed. As detailed above, TLR signals promote B cell activation and autoantibody production. In addition, TLR ligation synergizes with CD40 signaling to drive B cell cytokine production, including the regulatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-35. It therefore is likely that B cell-derived cytokines produced during antigen and TLR mediated activation, may function to limit spontaneous autoimmune GCs. Conversely, additional B-intrinsic cytokines likely enhance these events. By promoting TFH accumulation, excess IFN-γ drives dysregulated GCs and autoimmunity in the sanroque lupus model [61]. Since activated B effector 1 cells produce IFN-γ, it is possible that such cells represent a key IFN-γ source during humoral autoimmunity. Supporting this hypothesis, we have observed IFN-γ-producing was−/− B cells in diseased chimeras (SW Jackson, DJ Rawlings; unpublished data). It remains to be determined whether loss of B cell-intrinsic IFN-γ can restrain autoimmune GCs or whether alternative IFN-γ sources may compensate in vivo .

Conclusions

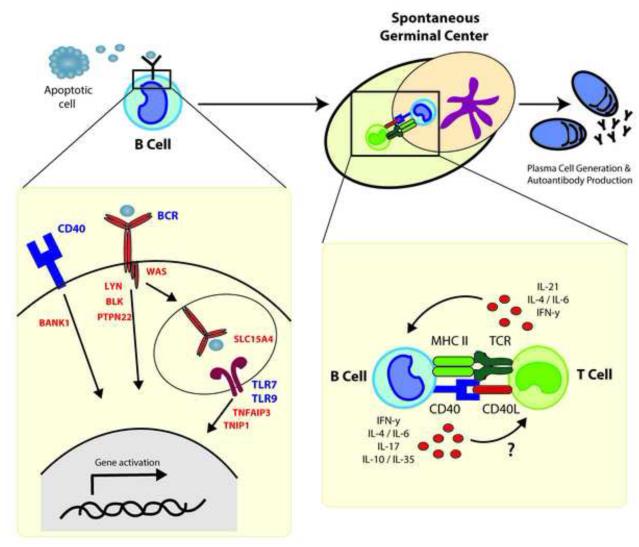

Recent data provide direct evidence that B cells can serve as primary drivers of autoimmunity. Figure 1 summarizes our proposed model in which, after encountering self-antigen, dysregulated B cell signaling is sufficient to promote B cell activation. This leads to recruitment and activation of autoreactive CD4+ T cells initiating GC development. Within developing GCs, B cells present antigen to T cells in the context of MHC Class II and likely also modulate the GC program via cytokine production.

Figure 1. Model for how altered B cell intrinsic signals may function to orchestrate autoimmune GC responses.

Schematic showing how alterations in signaling effectors in BCR and other co-stimulatory signals (including candidate GWAS risk variants or gene disruption) function to increase susceptibility to autoimmune disorders. In response to self-antigens (such as apoptotic cells) dysregulated signals downstream of the BCR, TLR and/or CD40 pathways, including exaggerated dual TLR and self-antigen specific BCR signals, function to facilitate spontaneous GC formation. Activated B cells promote activation of self-reactive T cells via self-antigen presentation - leading to a loss of T cell tolerance. Cytokine mediated feed-forward signaling likely further amplifies this process. The emerging GC reaction facilitates both affinity maturation of autoreactive B cells and generation of plasma cells secreting pathogenic class-switched autoantibodies. Examples of candidate risk alleles are displayed in red and include GWAS variants in PTPN22 (protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor 22); Src family kinases, LYN and BLK; SLC15A4 (solute carrier family 15, member 4); TNFAIP3 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3); TNIP1 (TNFAIP3 interacting protein 1); BANK1 (B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1); and loss of function in WAS (Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome).

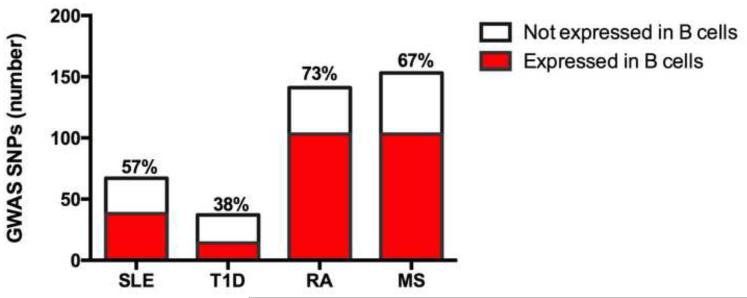

We have summarized the limited studies to date where B cell-intrinsic dysregulated signals leading to autoimmunity have been directly tested. Importantly, we predict that altered B cell function is likely to exert a much broader impact on human autoimmune pathogenesis than is currently appreciated. Indeed, examination of published GWAS in SLE, T1D, RA and MS demonstrates that a significant percentage of putative risk genes are expressed in B cells (Figure 2). Although not yet tested, we anticipate that a subset of these variants will exert B cell-intrinsic impacts in autoimmunity.

Figure 2. Autoimmune GWAS risk alleles include a large array of genes expressed in B cells.

Disease-associated risk variants in SLE, T1D, RA and MS were identified using a catalog of published GWAS alleles (www.genome.gov/gwastudies). B cell expression of risk genes was evaluated using the Immunological Genome Project database (http://www.immgen.org/databrowser/index.html). The total number of risk genes in each disease is shown, with the percentage of genes expressed in B cells listed and displayed in red.

Several important questions remain regarding how disease-associated signaling variants promote autoimmunity. For example, in addition to driving mature B cell activation and GC events, risk variants might directly impact the naïve B cell repertoire. Self-reactive B cells are removed from the repertoire via deletion, receptor editing and anergy. In addition, peripheral positive selection also modulates the naïve repertoire. Therefore, it will be important to address whether signaling variants that impact BCR, TLR, CD40 and/or BAFF (B cell activating factor of the TNF family) responses skew the repertoire toward greater baseline poly- and self-reactivity. In addition, as autoreactive B cells persist in the naïve repertoire even in healthy individuals, the mechanisms that constrain their initial activation and the impact of genetic risk variants on these events remains to be addressed.

Finally, an improved understanding of B cell mechanisms in autoimmunity carries the potential to develop new targeted therapies. Although B cell depletion has provided clinical benefit, its efficacy has been limited in other trials [62,63]; and long-standing B cell depletion carries a risk of infectious complications. Recent studies testing inhibitors of the BCR signaling effector, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, have shown utility in murine lupus models [64-66]. Thus, targeting dysregulated B cell signals using this or analogous agents directed at effectors downstream of BCR, TLR or CD40 may prove an effective therapeutic strategy.

Highlights.

B cells play multiple roles in autoimmune pathogenesis

A large proportion of autoimmune disease GWAS risk genes are expressed in B cells

Altered B cell signaling may be sufficient to initiate autoimmune germinal centers

B cell-intrinsic, dual BCR/TLR (especially TLR7) signals generate autoantibodies

B cell-derived cytokines may facilitate or sustain autoimmune GC responses

Acknowlegements

This work was supported by the NHLBI, NICHD, NIDDK and NIAID of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: R01HL075453 (DJR), R01AI084457 (DJR), R01AI071163 (DJR), DP3DK097672 (DJR) and K08AI112993 (SWJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support provided by the Benaroya Family Gift Fund; by a Cancer Research Institute Pre-doctoral Training Grant (NSK); by the ACR REF Rheumatology Scientist Development Award (SWJ); and by the Arnold Lee Smith Endowed Professorship for Research Faculty Development (SWJ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- 1.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–2581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pescovitz MD, Greenbaum CJ, Krause-Steinrauf H, Becker DJ, Gitelman SE, Goland R, Gottlieb PA, Marks JB, McGee PF, Moran AM, et al. Rituximab, B-lymphocyte depletion, and preservation of beta-cell function. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2143–2152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Turkiewicz A, Tchao NK, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, Vollmer T, Antel J, Fox RJ, Bar-Or A, Panzara M, Sarkar N, Agarwal S, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:676–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, Li EK, Thomas M, Kim HY, Leon MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721–731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyogoku C, Langefeld CD, Ortmann WA, Lee A, Selby S, Carlton VE, Chang M, Ramos P, Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, et al. Genetic association of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 with human SLE. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:504–507. doi: 10.1086/423790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottini N, Musumeci L, Alonso A, Rahmouni S, Nika K, Rostamkhani M, MacMurray J, Meloni GF, Lucarelli P, Pellecchia M, et al. A functional variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is associated with type I diabetes. Nat Genet. 2004;36:337–338. doi: 10.1038/ng1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KG, Clatworthy MR. FcgammaRIIB in autoimmunity and infection: evolutionary and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:328–343. doi: 10.1038/nri2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zenewicz LA, Abraham C, Flavell RA, Cho JH. Unraveling the genetics of autoimmunity. Cell. 2010;140:791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellmann U, Letz M, Herrmann M, Angermuller S, Kalden JR, Winkler TH. The evolution of human anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9258–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500132102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.William J, Euler C, Christensen S, Shlomchik MJ. Evolution of autoantibody responses via somatic hypermutation outside of germinal centers. Science. 2002;297:2066–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinuesa CG, Sanz I, Cook MC. Dysregulation of germinal centres in autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:845–857. doi: 10.1038/nri2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:205–217. doi: 10.1038/nri1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawlings DJ, Schwartz MA, Jackson SW, Meyer-Bahlburg A. Integration of B cell responses through Toll-like receptors and antigen receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:282–294. doi: 10.1038/nri3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou B, Saudan P, Ott G, Wheeler ML, Ji M, Kuzmich L, Lee LM, Coffman RL, Bachmann MF, DeFranco AL. Selective utilization of Toll-like receptor and MyD88 signaling in B cells for enhancement of the antiviral germinal center response. Immunity. 2011;34:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlomchik MJ. Activating systemic autoimmunity: B's, T's, and tolls. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green NM, Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptor driven B cell activation in the induction of systemic autoimmunity. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan KE, Mullen CA, Blaese RM, Winkelstein JA. A multiinstitutional survey of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994;125:876–885. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker-Herman S, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Schwartz MA, Jackson SW, Hudkins KL, Liu C, Sather BD, Khim S, Liggitt D, Song W, et al. WASp-deficient B cells play a critical, cell-intrinsic role in triggering autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2033–2042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groom JR, Fletcher CA, Walters SN, Grey ST, Watt SV, Sweet MJ, Smyth MJ, Mackay CR, Mackay F. BAFF and MyD88 signals promote a lupuslike disease independent of T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1959–1971. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehlers M, Fukuyama H, McGaha TL, Aderem A, Ravetch JV. TLR9/MyD88 signaling is required for class switching to pathogenic IgG2a and 2b autoantibodies in SLE. J Exp Med. 2006;203:553–561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •22.Teichmann LL, Schenten D, Medzhitov R, Kashgarian M, Shlomchik MJ. Signals via the adaptor MyD88 in B cells and DCs make distinct and synergistic contributions to immune activation and tissue damage in lupus. Immunity. 2013;38:528–540. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. These authors provide a detailed analysis of how B cell-intrinsic MyD88 signals in transgenic, self-reactive B cells modulate autoantibody production and disease in a lupus model.

- 23•.Hua Z, Gross AJ, Lamagna C, Ramos-Hernandez N, Scapini P, Ji M, Shao H, Lowell CA, Hou B, DeFranco AL. Requirement for MyD88 signaling in B cells and dendritic cells for germinal center anti-nuclear antibody production in Lyn-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2014;192:875–885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen SR, Kashgarian M, Alexopoulou L, Flavell RA, Akira S, Shlomchik MJ. Toll-like receptor 9 controls anti-DNA autoantibody production in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 2005;202:321–331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berland R, Fernandez L, Kari E, Han JH, Lomakin I, Akira S, Wortis HH, Kearney JF, Ucci AA, Imanishi-Kari T. Toll-like receptor 7-dependent loss of B cell tolerance in pathogenic autoantibody knockin mice. Immunity. 2006;25:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lartigue A, Courville P, Auquit I, Francois A, Arnoult C, Tron F, Gilbert D, Musette P. Role of TLR9 in anti-nucleosome and anti-DNA antibody production in lpr mutation-induced murine lupus. J Immunol. 2006;177:1349–1354. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Jackson SW, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Khim S, Schwartz MA, Li QZ, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Liggitt D, Rawlings DJ. Opposing impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 signals on autoantibody repertoire and systemic inflammation. J Immunol. 2014;192:4525–4532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deane JA, Pisitkun P, Barrett RS, Feigenbaum L, Town T, Ward JM, Flavell RA, Bolland S. Control of toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh ER, Pisitkun P, Voynova E, Deane JA, Scott BL, Caspi RR, Bolland S. Dual signaling by innate and adaptive immune receptors is required for TLR7-induced B-cell-mediated autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16276–16281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209372109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Soni C, Wong EB, Domeier PP, Khan TN, Satoh T, Akira S, Rahman ZS. B Cell-Intrinsic TLR7 Signaling Is Essential for the Development of Spontaneous Germinal Centers. J Immunol. 2014;193:4400–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Together with Ref 28, these papers: a) identify the specific role for B cell intrinsic TLR7 vs. TLR9 signaling in modulating the outcome of autoimmune GC reactions; and b) show that cell intrinsic TLR7 signals are also required for spontaneous GC responses in non-autoimmune mice.

- 32.Sun X, Wiedeman A, Agrawal N, Teal TH, Tanaka L, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Bolland S, Buechler MB, Hamerman JA, et al. Increased ribonuclease expression reduces inflammation and prolongs survival in TLR7 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2013;190:2536–2543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen N, Fu Q, Deng Y, Qian X, Zhao J, Kaufman KM, Wu YL, Yu CY, Tang Y, Chen JY, et al. Sex-specific association of X-linked Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) with male systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15838–15843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001337107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Ortiz H, Velazquez-Cruz R, Espinosa-Rosales F, Jimenez-Morales S, Baca V, Orozco L. Association of TLR7 copy number variation with susceptibility to childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Mexican population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1861–1865. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawasaki A, Furukawa H, Kondo Y, Ito S, Hayashi T, Kusaoi M, Matsumoto I, Tohma S, Takasaki Y, Hashimoto H, et al. TLR7 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3' untranslated region and intron 2 independently contribute to systemic lupus erythematosus in Japanese women: a case-control association study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R41. doi: 10.1186/ar3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Sun LD, Ye DQ, Hu Z, Xu JH, Cai ZM, Huang W, Zhao GP, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, Ortmann W, Kosoy R, Ferreira RC, Nordmark G, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi T, Shimabukuro-Demoto S, Yoshida-Sugitani R, Furuyama-Tanaka K, Karyu H, Sugiura Y, Shimizu Y, Hosaka T, Goto M, Kato N, et al. The histidine transporter SLC15A4 coordinates mTOR-dependent inflammatory responses and pathogenic antibody production. Immunity. 2014;41:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM, Armes J, Grail D, Hodgson G, Maglitto R, Stacker SA, Dunn AR. Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell. 1995;83:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Y, Harder KW, Huntington ND, Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM. Lyn tyrosine kinase: accentuating the positive and the negative. Immunity. 2005;22:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •40.Lamagna C, Hu Y, DeFranco AL, Lowell CA. B cell-specific loss of Lyn kinase leads to autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2014;192:919–928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. Together with Ref 23, these studies demonstrate: a) B cell specific lyn deletion is sufficient to promote lupus-like autoimmunity; and b) B cell specific MyD88 signals are crucial to this process.

- 42.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, Moser KL, Tsao BP, Vyse TJ, Langefeld CD, Nath SK, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40:204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, Lee AT, Chung SA, Ferreira RC, Pant PV, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu R, Vidal GS, Kelly JA, Delgado-Vega AM, Howard XK, Macwana SR, Dominguez N, Klein W, Burrell C, Harley IT, et al. Genetic associations of LYN with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:397–403. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Surolia I, Pirnie SP, Chellappa V, Taylor KN, Cariappa A, Moya J, Liu H, Bell DW, Driscoll DR, Diederichs S, et al. Functionally defective germline variants of sialic acid acetylesterase in autoimmunity. Nature. 2010;466:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature09115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, Ardlie KG, Huang Q, Smith AM, Spoerke JM, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:330–337. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47••.Dai X, James RG, Habib T, Singh S, Jackson S, Khim S, Moon RT, Liggitt D, Wolf-Yadlin A, Buckner JH, et al. 2013;123:2024–2036. doi: 10.1172/JCI66963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Zhang J, Zahir N, Jiang Q, Miliotis H, Heyraud S, Meng X, Dong B, Xie G, Qiu F, Hao Z, et al. 2011;43:902–907. doi: 10.1038/ng.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••. These groups describe murine knock-in models of the autoimmune-associated PTPN22 variant and show that the variant promotes enhanced TCR and BCR signaling and triggers autoimmunity in a mixed genetic background. This work clearly highlights the utility of detailed murine modeling of candidate human autoimmune risk variants.

- 49.Yokoyama K, Su Ih IH, Tezuka T, Yasuda T, Mikoshiba K, Tarakhovsky A, Yamamoto T. BANK regulates BCR-induced calcium mobilization by promoting tyrosine phosphorylation of IP(3) receptor. EMBO J. 2002;21:83–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aiba Y, Yamazaki T, Okada T, Gotoh K, Sanjo H, Ogata M, Kurosaki T. BANK negatively regulates Akt activation and subsequent B cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozyrev SV, Abelson AK, Wojcik J, Zaghlool A, Linga Reddy MV, Sanchez E, Gunnarsson I, Svenungsson E, Sturfelt G, Jonsen A, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:211–216. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong FS, Wen L, Tang M, Ramanathan M, Visintin I, Daugherty J, Hannum LG, Janeway CA, Jr., Shlomchik MJ. Investigation of the role of B-cells in type 1 diabetes in the NOD mouse. Diabetes. 2004;53:2581–2587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noorchashm H, Lieu YK, Noorchashm N, Rostami SY, Greeley SA, Schlachterman A, Song HK, Noto LE, Jevnikar AM, Barker CF, et al. I-Ag7-mediated antigen presentation by B lymphocytes is critical in overcoming a checkpoint in T cell tolerance to islet beta cells of nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:743–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hulbert C, Riseili B, Rojas M, Thomas JW. B cell specificity contributes to the outcome of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:5535–5538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.Molnarfi N, Schulze-Topphoff U, Weber MS, Patarroyo JC, Prod'homme T, Varrin-Doyer M, Shetty A, Linington C, Slavin AJ, Hidalgo J, et al. MHC class II-dependent B cell APC function is required for induction of CNS autoimmunity independent of myelin-specific antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2921–2937. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. The authors demonstrate that B cell-mediated antigen presentation plays a key role in disease pathogenesis in an EAE animal model.

- 56.Lund FE. Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes-key regulators of immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57•.Bermejo DA, Jackson SW, Gorosito-Serran M, Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Amezcua-Vesely MC, Sather BD, Singh AK, Khim S, Mucci J, Liggitt D, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase initiates a program independent of the transcription factors RORgammat and Ahr that leads to IL-17 production by activated B cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:514–522. doi: 10.1038/ni.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Shen P, Roch T, Lampropoulou V, O'Connor RA, Stervbo U, Hilgenberg E, Ries S, Dang VD, Jaimes Y, Daridon C, et al. IL-35-producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature. 2014;507:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •. These two studies identify the novel capacity for activated B cells to generate IL-17 and IL-35, respectively; broadening the array of key cytokines produced by B cells under various activation conditions.

- 59.Dang VD, Hilgenberg E, Ries S, Shen P, Fillatreau S. From the regulatory functions of B cells to the identification of cytokine-producing plasma cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;28:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sweet RA, Lee SK, Vinuesa CG. Developing connections amongst key cytokines and dysregulated germinal centers in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee SK, Silva DG, Martin JL, Pratama A, Hu X, Chang PP, Walters G, Vinuesa CG. Interferon-gamma excess leads to pathogenic accumulation of follicular helper T cells and germinal centers. Immunity. 2012;37:880–892. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merrill JT, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ, Shanahan JC, Latinis KM, Oates JC, Utset TO, Gordon C, Isenberg DA, Hsieh HJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately-to-severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: the randomized, double-blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:222–233. doi: 10.1002/art.27233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, Looney RJ, Fervenza FC, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Maciuca R, Zhang D, Garg JP, Brunetta P, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the Lupus Nephritis Assessment with Rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1215–1226. doi: 10.1002/art.34359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rankin AL, Seth N, Keegan S, Andreyeva T, Cook TA, Edmonds J, Mathialagan N, Benson MJ, Syed J, Zhan Y, et al. Selective inhibition of BTK prevents murine lupus and antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. J Immunol. 2013;191:4540–4550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, Verner E, Loury D, Chang B, Li S, Pan Z, Thamm DH, Miller RA, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mina-Osorio P, LaStant J, Keirstead N, Whittard T, Ayala J, Stefanova S, Garrido R, Dimaano N, Hilton H, Giron M, et al. Suppression of glomerulonephritis in lupusprone NZB × NZW mice by RN486, a selective inhibitor of Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2380–2391. doi: 10.1002/art.38047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]