Abstract

Lymph nodes are initial sites for cancer metastasis in many solid tumors. However, their role in cancer progression is still not completely understood. Emerging evidence suggests that the lymph node microenvironment provides hospitable soil for the seeding and proliferation of cancer cells. Resident immune and stromal cells in the lymph node express and secrete molecules that may facilitate the survival of cancer cells in this organ. More comprehensive studies are warranted to fully understand the importance of the lymph node in tumor progression. Here, we will review the current knowledge of the role of the lymph node microenvironment in metastatic progression.

Keywords: Lymph node, metastasis, lymphatic vessels, chemokine, clonality, lymphangiogenesis

1. Introduction

Cancer metastasis is a complex, multi step process that involves the dissemination of cancer cells from the primary site to distant organs [1]. Several recent studies have advanced our knowledge of the spread of tumor cells via the blood stream, however, less is known about the process of lymphatic metastasis. Mounting evidence suggests that lymphatic metastasis is not an entirely passive process as previously hypothesized, but is regulated at multiple steps including the transit of tumor cells via the lymphatic vessels and the successful seeding in draining lymph nodes [2]. The presence of tumor cells in regional or sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) has important clinical significance as it is associated with disease progression, poor prognosis and often determines the choice of therapies [3–5]. The increasing recognition of the importance of lymph node metastasis in cancer biology has prompted recent studies to unravel the molecular signals and cellular changes involved in this complex process. Some of these changes include lymphangiogenesis, the expansion of immunosuppressive cells, up-regulation of chemokines and cytokines, and blood vessel remodeling in the lymph node. These events help facilitate tumor cell entry, colonization and survival in the lymph node. However, the ultimate fate of tumor cells in the lymph node is still controversial [6].

Several studies have elucidated how tumor cells are attracted to the lymph node by chemokine signals that are often secreted by stromal or immune cells in the lymph node microenvironment [7]. In addition to attracting tumor cells to the lymph node, chemokines play an important role in modulating immune or stromal cell activity. Furthermore, the role of lymphatic vessels and lymphangiogenesis in altering the local inflammatory response and promoting an immunosuppressive microenvironment in the lymph node is critical for tumor cell dissemination to this organ [8]. Recent progress in lymphatic vessel biology, including the development of sophisticated intravital imaging techniques for monitoring the process of lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastases has led to the appreciation of the lymphatic system as a major contributor to cancer progression [9–15]. In this review we discuss recent progress in our understanding of the mechanisms involved in lymph node metastasis and the potential role of the lymph node in facilitating tumor cell proliferation and metastases to distant organs.

2. The lymph node, lymphatic vessels and lymphangiogenesis

The lymphatic vasculature is a series of vessels throughout the body that play important roles in tissue homeostasis, fluid balance, immune function, absorption of dietary fat and lipid transport. In addition to their role in normal physiology, lymphatic vessels play critical roles in pathological conditions including inflammation and cancer [16, 17]. Lymphatic endothelial cells express several molecular markers that include LYVE-1, Prox1, podoplanin (gp38), VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, neuropilin-2, angiopoietin-1 and CCL21. In peripheral tissues, initial lymphatic vessels are thin-walled vessels that absorb fluid and cells from tissues. These vessels are porous and easily accessed by cells as they have overlapping endothelial micro-valves, intermittent basement membrane and lack pericyte and smooth muscle coverage [18]. Initial lymphatics carry lymphatic fluid into deeper pre-collecting vessels, then into larger collecting lymphatic vessels and finally back into the bloodstream [19]. In pathological conditions including cancer, lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes participate in disease progression and undergo remodeling in response to growth factors, chemokines and other signaling molecules secreted by tumor cells or other cells in the tumor microenvironment [17].

2.1. Sentinel lymph nodes: A niche for tumor growth

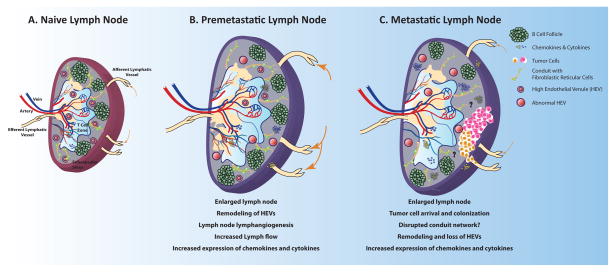

Tumor cell metastasis to distant sites is often preceded by changes in the microenvironment of the metastatic organ in preparation for the arrival and successful colonization of tumor cells [20]. The crosstalk between the tumor cell (‘the seed’) and the microenvironment (‘the soil’) was observed and described by Stephen Paget in 1889 and came to be known as the ‘Seed and Soil’ hypothesis [21]. Many decades later, we are beginning to uncover the cellular and molecular changes in the metastatic lymph node microenvironment prior to the arrival of tumor cells. Several studies have elucidated some distinctive features of a pre-metastatic SLN including increased lymphangiogenesis and lymph flow [22], remodeling of high endothelial venules (HEVs) [23, 24], recruitment of myeloid cells and diminution of effector lymphocyte count and/or function [25] (Figure 1). In mouse models of cancer as well as in human patients, the HEVs in the pre-metastatic SLN have decreased vessel-wall thickness and increased cross-sectional vessel diameter that transition into thin-wall enlarged blood vessels [23, 24, 26]. The proximity of SLNs to the tumor may lead to an increased concentration in lymph-transported molecules that orchestrate these events. As tumor cells metastasize to lymph nodes or other tissues, distant lymph nodes may also undergo changes. Immune cell composition can be altered in tumor-free, non-SLNs, suggesting that SLN status is not required for changes to occur [27]. SLN lymphangiogenesis, but not angiogenesis, was also found to be a strong predictor of further lymph node metastasis [28].

Figure 1.

Alterations to tumor draining lymph nodes during cancer progression. A) Naïve lymph nodes are sites where foreign, pathogenic or self-antigens accumulate and adaptive immune responses are generated. Optimal interactions between antigen-loaded-dendritic cells and effector T lymphocytes in the lymph node stimulate effective immune responses that eliminate foreign and pathogenic antigens. B) Prior to cancer cell dissemination, tumor draining lymph nodes undergo many remodeling processes, including lymph node lymphangiogenesis, alterations in high endothelial venules, increases in chemokine and cytokine production and alterations in immune cell composition. These changes are thought to enable the growth of cancer cells that are seeded in the lymph node. C) Cancer bearing lymph nodes, undergo further changes, including the loss of high endothelial venules, regression of lymphangiogenic vessels, and impairment of lymphocyte recruitment. These changes inhibit adaptive immune responses and may enable the further spread of cancer cells to distant organs.

In addition to the remodeling of the vasculature, SLN undergo expansion of immune cell and stromal cell populations and appear to have a largely immunosuppressive cytokine environment. Several cytokines have been found to play a prominent role in the immunosuppression of SLNs. In several studies IL-10, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine, was increased in SLNs relative to non-SLNs [29, 30]. Interestingly, IL-10 production was higher in tumor-free SLNs compared to lymph nodes with tumor [30, 31]. Other immunosuppressive cytokines and molecules such as TGF-β, GM-CSF, and PGE2 from primary tumor and/or lymph nodes can influence the immune status of the SLN [25, 32, 33]. The SLNs become increasingly immunocompromised with an increase in primary tumor size [32]. It is possible however that both the primary tumor and SLNs are sources of immunosuppressive cytokines. It is also believed that recruitment of myeloid immune cell populations from the blood circulation in a premetastatic setting will promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates the growth and expansion of tumor cells at that site [27]. Recent studies suggest that CD8+ T cells are capable of killing myeloid cells in SLNs as a potential mechanism to prevent colonization of tumor cells [34]. Taken together these studies support the phenomenon of a premetastatic niche in SLNs that is initiated by the primary tumor prior to the physical presence of metastatic cancer cells in the SLN.

2.2. Molecular signals precondition the lymph node microenvironment

The most well documented aspect of the premetastatic niche in SLNs is lymph node lymphangiogenesis driven by VEGF-A or VEGF-C [35, 36], which also correlates with increased distant metastases in these studies. VEGF-C-PI3K mediated signaling is important for remodeling the lymph node prior to tumor cell arrival by stimulating LEC proliferation, leading to tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis. This signaling leads to activation of integrin α4β1 on lymph node lymphatic endothelium, which attracts vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) expressing tumor cells, thereby promoting lymph node metastasis [37]. Erythropoietin (EPO) was also shown to act directly on lymphatic endothelial cells, enhancing lymph node lymphangiogenesis [38] and tumor metastasis. EPO also increased VEGF-C expression in inflammatory macrophages in draining lymph nodes. Similar to other studies of inflammation in non-lymphoid tissue, multiple growth factors may lead to lymphangiogenesis directly, or indirectly via up-regulation of VEGF-C.

Several studies have shown that high endothelial venule-associated molecules are down-regulated in the pre-metastatic lymph node. Specifically, loss of bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4) in HEVs was associated with HEV remodeling [39], suggesting that BMP-4 is an inhibitor of lymph node vascular remodeling. Loss of peripheral node addressin (PNAd), an L-selectin ligand on the surface of HEVs that play an important role in lymphocyte homing, was observed in metastatic lymph nodes [24]. These findings suggest that primary tumors can remodel HEVs in SLNs to inhibit immune responses while providing any arriving cancer cells with nutrients through sustained blood flow.

In addition to effects on lymphatic endothelium, molecular signaling also regulates the immune cell populations in SLNs. By unknown mechanisms, distal tumor cells cause the loss of lymph node CCL21, impairing lymphocyte homing [40]. In contrast, Stat-3-S1PR1 signaling in myeloid cells from tumor free lymph nodes in cancer patients was increased [41]. Blockade of this pathway in animal studies led to a decrease in the incidence of metastasis. Another recent study by Ogawa and colleagues [25] demonstrated that dendritic cells (DC) in the sub-capsular sinus (SCS) of a premetastatic lymph node produced COX-2-derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 stimulated the EP3 receptor on DCs and up-regulated the expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) as well as promoted the accumulation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are immunosuppressive. SDF-1α increased the accumulation of CXCR4+ tumor cells and facilitated the formation of metastatic lesions in the lymph node, as seen previously [7]. This study further confirmed the importance of this signaling pathway by using inhibitors of PGE2, together with SDF-1α and EP3 receptor antagonists, which inhibited lymph node metastasis in a Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model. These studies suggest that tumor-draining lymph nodes are conditioned prior to cancer cell arrival by undergoing stromal remodeling, recruiting immune cells and increasing production of chemokines. Together these alterations create a permissive microenvironment for metastases.

2.3. Lymphatic vessels: A highway for tumor metastases

A characteristic feature of rapidly growing solid tumors is an expansion of the surrounding lymphatic network. However, functional lymphatic vessels are restricted to the periphery of solid tumors [9]. Similar observations were documented in breast cancer patients [42] and advanced metastatic melanoma patients [39], where local tumor invasion correlated with high lymphatic vessel density in the tumor margin. The lack of functional lymphatic vessels inside the tumor increases interstitial fluid pressure and enhances lymph flow to the SLN [11]. A similar observation was made in experimental mouse models of cancer, where overexpression of lymphangiogenic growth factors, VEGF-C and VEGF-D, further enhanced peripheral tumor lymphatic vessel growth and increased lymph node metastasis [43–46]. VEGF-C also up-regulates CCL21 production in lymphatic endothelium, thereby promoting lymphatic entry of CCR7+ tumor cells [47]. Once tumor cells arrive at the lymphatic vessels, it is not yet known whether tumor cells actively or passively gain access to lymphatic capillaries.

Tumor-derived VEGF-C/D can increase contraction of proximal collecting lymphatic vessels [48], thus increasing lymph flow and potentially enhancing tumor cell dissemination. By reducing lymphatic vessel diameters, tumor spread was reduced, suggesting that tumor-induced remodeling of lymphatic vessels enhances metastasis to SLNs [11, 49, 50]. Additionally, it was shown that lymph transport in lymphatics downstream of SLN is increased and correlated with metastatic disease progression [51]. More work needs to be done to determine whether the flow patterns are altered due to the effect of VEGF-C/D on lymphatic capillaries or whether these observations are due to a direct effect on collecting lymphatic vessels. In the case of melanoma, the prevailing view is that lymph flow also promotes dissemination of cancer cells that deposit in tissues between the primary tumor and the lymph nodes, resulting in “in-transit metastases”. In later stages of tumor progression, in-transit tumor nodules were found in the collecting lymphatic vessels [52] and ultimately led to lymph node metastasis. It is generally believed that the underlying genetics of a tumor cell determines its metastatic pattern. Yet, little is known about the mechanism of how tumor cells navigate and potentially impair lymph flow, attach to lymphatic endothelium and eventually extravasate into cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue.

When lymphatic vessels are obstructed, collateral lymphatic vessels can compensate for the reduction in lymphatic capacity [14, 53, 54]. Little is known about the potential role of collateral lymphatic vessels in lymphatic metastasis. It was recently shown that lymphadenectomy of the popliteal lymph node led to alternative lymph drainage to the inguinal lymph nodes through pre-existing collateral lymphatic vessels. The drainage patterns of cancer metastasis after lymphadenectomy were rerouted, consistent with the patterns of re-directed lymphatic drainage [55]. These results call into question whether regional lymphadenectomies are sufficient to eliminate all lymph node metastases since new avenues of transport to alternative lymph nodes may be available.

2.4. Cancer cell survival in the lymphatic system

Upon entering the lymphatic vessels, cancer cells are faced with the challenge of a hypoxic environment [56]. The availability of oxygen within lymphatic vessels is influenced by tissue type, metabolic activity of lymphatic endothelium and proximity to blood vessels within the tissue. A similar challenge is faced once cancer cells reach the lymph node and enter the SCS. Under normal physiological conditions, the SCS is devoid of blood vessels and red blood cells, thus oxygen availability is scarce [57]. Cancer cells in the SCS are located 100–200μM from existing blood vessels within the paracortex, which is in agreement with the limits of the oxygen diffusion distance. Upon encountering a hypoxic environment, cells can either adapt to the low oxygen setting or secure an oxygen and nutrient supply by migrating to or recruiting blood vessels [58] in order to meet their energetic and biosynthetic requirements. Angiogenesis has been extensively documented to occur in response to a hypoxic environment in tumors. Production of proangiogenic factors like VEGF by hypoxic tumor and host cells can lead to angiogenesis in an attempt to eliminate local hypoxia [59, 60]. However, increases in vessel density in lymph node metastasis have not been documented to date [61–63]. Hypoxic cancer cells have the capacity to adapt in an environment that lacks sufficient levels of oxygen by up-regulating expression of glucose transporters and associated genes for anaerobic glycolysis, while local normoxic cells can utilize the resulting lactate as their energy source [64]. In addition to the effects of hypoxia on tumor cell metabolism, a chronic hypoxic environment has also been shown to select for clones that are more aggressive and metastatic [65, 66]. This selection and adaptation may enable cancer cells to survive in the SCS until invasion into the blood vessel containing parenchyma is achieved. Alternatively, micrometastatic lesions may enter a state of dormancy while in the avascular SCS. Instead of inducing an “angiogenic switch”, tumor cells may escape this dormancy by invading the lymph node parenchyma where nodal blood vessels reside. The molecular triggers for the invasion of the parenchyma are not well understood, but chemokines might be one component [67]. One may also expect a greater degree of cellular activity and proliferation at the invasive edge of the metastatic lesion. Further investigation is warranted to fully understand the metabolic state and bioenergetic needs of tumor cells in the lymph node.

3. Chemokine signaling in lymph node metastases

After cancer cells arrive in the lymph node, further changes occur (Figure 1). Chemical signals known as chemokines help direct cells, including cancer cells, to new locations. Chemokines are a superfamily of cytokine-like molecules that can induce cytoskeletal rearrangement and directional migration of cells via their association with specific G-protein coupled receptors. Chemokines play critical roles in the migration, proliferation and maturation of immune cells in the lymph node. A growing body of literature suggests that various chemokine-receptor signaling pathways also play a central role in trafficking different cancer cell types to the lymph node. Chemokines can attract cancer cells to lymphatic vessels in the primary site, as well as attract metastatic tumor cells to secondary sites after they invade blood or lymphatic vessels. A study by Muller et al. showed that some human breast cancer cells have increased expression of several chemokine receptors including CXCR4 and CCR7 compared to normal mammary epithelial cells and this correlates with their ability to metastasize to lymph nodes [7]. Signaling through the CXCR4 and CCR7 receptors enhance actin polymerization and pseudopodia formation in breast carcinoma cells, resulting in increased motility and invasive phenotype of these cells. The ligands for these receptors are CXCL12/SDF1α for CXCR4, and CCL19/MIP-3β and CCL21/6Ckine for CCR7, all of which are expressed in the lymph node microenvironment and can act as potent chemoattractant signals for cancer cells. To test the importance of SDF1α/CXCR4 signaling in facilitating metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer, anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody was used to neutralize its effects in vivo. Inhibition of SDF1α/CXCR4 signaling significantly decreased lung and lymph node metastasis compared to isotype-treated control mice [7]. In addition to breast cancer, the importance of CCR7 signaling in mediating lymph node metastasis was elucidated in a mouse model of melanoma [68] and esophageal cancers [69]. Most recently, a role for the CCL1/CCR8, chemokine-receptor signaling pathway was demonstrated to be important for melanoma tumor cell entry into the lymph node parenchyma [67]. CCL1 is expressed by lymphatic endothelial cells in the sub-capsular sinus of the lymph node and facilitates CCR8+ tumor cell entry into this organ. Blocking this pathway significantly inhibited tumor cell entry into the lymph node from the afferent lymphatic vessel. Taken together, these studies show that chemokine-receptor signaling plays a crucial role in the active transport and delivery of tumor cells into the SCS and lymph node parenchyma. The importance of a specific chemokine in regulating tumor cell entry or exit from the SLN is likely dependent on the expression level of that molecule in the lymph node and the presence of its cognate receptor on cancer cells. In addition to a direct role for chemokine signaling to attract tumor cells into the SCS of the lymph node, these molecules play important roles in immune cell chemotaxis and may be involved in establishing a pro-tumoral microenvironment in the lymph node. Thus, identifying and targeting key chemokine-receptor signaling pathways that influence tumor cell growth in the lymph node is crucial for eliminating lymph node metastases.

4. Evading immune surveillance in the lymph node

Naïve lymph nodes are the site of immune regulation where foreign, pathogenic or self-antigens accumulate. Optimal interactions between antigen-loaded-dendritic cells (DCs) and effector T lymphocytes in the lymph node facilitate adaptive immune responses that eliminate foreign and pathogenic antigens. In cancer, functional lymphatic vessels on the periphery of tumors are the physical connection between the primary tumor and SLNs. Rogue tumor cells have evolved ways of evading immune surveillance mechanisms in the lymph node and thus are able to successfully colonize and proliferate in this metastatic site. The immune microenvironment in the lymph node consists of three major cell populations, stromal, myeloid and lymphoid. Myeloid cells consist of macrophages and dendritic cells, while lymphoid cells are represented by T and B lymphocytes [70, 71]. The stromal population is comprised of fibroblast reticular cells and blood and lymphatic endothelial cells. The myeloid cells occupy only a small portion of the entire cell population in the lymph node. However, dendritic cells greatly influence immune outcome within the lymph nodes. The absence or immaturity of dendritic cells in the SLNs leads to limited T cell responses against the tumor [72, 73]. In addition, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have been shown to recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs) and inhibit proliferation of T cells in SLNs [74]. Likewise, recent studies have elucidated multiple roles for stromal cells in regulating T cell fate and function in the lymph node. During chronic inflammation, activated LECs modulate the maturation of DCs and suppress their ability to induce T cell proliferation, thus preventing an immune response [75]. LECs also have the ability to delete autoreactive T cells and promote immune tolerance by constitutively expressing and presenting self-antigens on MHC class I molecules. LECs lack the co-stimulatory molecules necessary to activate CD8+ T cells but express high levels of the immune checkpoint inhibitory ligand PD-L1 [76]. This leads to LEC scavenging of self-antigens in the lymph fluid, followed by processing and cross-presentation of these antigens on MHC class I molecules, which then drives deletional tolerance of naïve CD8+ T cells [77]. This tolerance appears to be critical for the survival of tumor cells in lymph nodes since direct implantation of tumor cells into the lymph node led to rejection by a CD8+ T cell response [78].

Emerging evidence suggests that metastatic tumors proliferate in their new environment by evading host immune system effector functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [79]. A lower percentage of effector T cells were found in metastatic and premetastatic lymph nodes [27]. Lymphocyte recruitment into the SLN is primarily via HEVs although some immune cells can also traffic into the lymph node via the draining afferent lymphatic vessels. Cancer-induced remodeling of HEVs can potentially impair immune cell trafficking to the lymph node, promoting tumor cell survival. As mentioned earlier, dendritic cell education of T cells may also be impaired, further contributing to the decrease in functional lymphocytes [72, 73]. Colorectal cancer patients with lymph node metastasis had a significant increase in CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs compared to patients with no lymph node metastasis [80]. Increased Tregs were associated with a functional impairment of CD8+ T cells [80]. Among T cell populations in the lymph node, tumor-specific T cells in metastatic lymph nodes were functionally tolerant [81]. Several mechanisms have been shown to account for this tolerance including induction of tolerance by lymphatic endothelial cells [77]. Furthermore, antigen presented by tumor cells or antigen presenting cells in late-stage tumors led to proliferation of CD8+ T cells that lacked effector function [82].

While much attention has been paid to T cells, B cells also impact metastatic tumor growth in the lymph node [83]. B cells in the SLNs are able to process and present antigen to naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, stimulating the activation of effector T cell response to tumor antigens [84, 85]. These effector CD8+T cells in the SLN secrete anti-tumor cytokines such as IFN-γ that mediate tumor regression. Activated B cells also have the ability to undergo clonal expansion and secrete tumor specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the SLN in response to tumor antigens draining to this site [86, 87]. Taken together, these studies underscore the role of B cells as efficient antigen presenting cells and regulators of T cell activation in the tumor draining lymph node.

5. Clonal dissection of lymph node metastases in solid tumors

There is much speculation about the chronological sequence of events in tumor cell metastasis from a primary location to a secondary or tertiary site. Several studies have performed lineage tracing and genomic sequencing on primary and metastatic tumors in an attempt to understand this phenomenon. A recent study characterized the clonal evolution of tumor cells in a genetically engineered mouse model of small cell lung carcinoma at metastatic sites including the lymph node and liver [88]. This model recapitulates human disease by harboring lung-specific deletion of the tumor suppressor genes, TP53 and RB1 and progressing from small neuro-endocrine bodies in the lung to frequent metastases in the lymph node and liver. Genomic sequencing of the primary tumor and lymph node metastases in multiple mice bearing small cell lung carcinoma revealed that tumor cells that colonized the lymph node were polyclonal as multiple primary tumor subclones were identified in the draining lymph nodes.

Another study reported a PCR-based assay to determine somatic variation in hypermutable polyguanine (poly-G) repeats as a measure of the mitotic history and clonal make-up in human cancer [89]. In a cohort of 22 patients, poly-G variants were detected in 91% of tumors and phylogenetic trees were constructed to determine the metastatic progression for each patient, most of whom were advanced colon cancer patients. This analysis revealed varying degrees of intratumor heterogeneity among patients. For example, two patients with colon cancer and distant metastases to the ovary revealed that the ovarian tumor was clonally distinct from the primary tumor and lymph node metastasis. However, two independent samples from the lymph node metastasis revealed that it had an identical genetic composition to the primary tumor, suggesting that the pool of genetically divergent clones in the primary tumor was also found in lymph node lesions. These data suggest that similar to the primary tumor, lymph node metastases represent a polyclonal population of tumor cells. This observation could have multiple implications for node positive patients. First, using targeted therapy for the treatment of lymph node metastases could be challenging. Second, if tumor cells exit the lymph node, it is possible that multiple clones could simultaneously colonize distant sites. Finally, new driver mutations could arise in the lymph node that give rise to polyclonal distant metastases that are different from the primary tumor.

Given the polyclonality of lymph node metastases, it is unclear whether a single targeted therapy can eliminate disease. As with studies from primary tumors, lymph node metastases may develop mechanisms of acquired resistance from these therapies. The treatment strategy could be more complicated in cases where these resistance mechanisms may differ from those of the primary tumor. Clinicians and biologists are becoming increasingly aware that the mechanisms of survival and proliferation of tumor cells may be microenvironment specific, making treatment strategies complicated.

6. Lymph node metastases: Clinical perspectives

Primary tumor resection and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) have been part of the standard treatment for breast cancer patients with metastases in the SLN. These surgeries attempt to eliminate all disease provided the cancer is in the early stages and has not metastasized to distant organs. However, ALND has several devastating short-term and long-term side effects including seromas, infections, reduced arm movement and lymphedema [90]. Due to these complications, two recent randomized clinical trials were carried out to determine if axillary dissection improves survival in early stage (I or II) breast cancer patients with a positive SLN. Both trials, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial [91] and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 23-01 trial [92], showed no overall survival benefit to ALND with standard chemo-radiation therapy when compared to standard chemo-radiation therapy without axillary surgery. Similarly, the recent AMAROS (After Mapping the Axilla: Radiotherapy or Surgery?) trial showed no difference in overall survival in a randomized trial comparing ALND to radiotherapy in SLN positive patients, with the radiotherapy group experiencing less lymphedema [93, 94]. Results from these studies show that axillary dissection could be avoided in patients with early stage breast cancer and limited SLN involvement, as systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy sterilize disease in the node. The reduced number of axillary surgeries now being performed are expected to lower the incidence of lymphedema and other complications in breast cancer patients. However, long-term follow-up studies need to be undertaken to assess whether residual disease in the node may contribute to relapse in patients who do not undergo ALND. Studies are warranted to understand the fate of cancer cells in lymph nodes of patients with early stage disease that forgo ALND as well as understanding the pathways traveled by metastatic tumor cells in patients with advanced disease involving multiple lymph nodes and distant organs. In this review series, Nathanson et. al. [5], provide a comprehensive review of our understanding of lymph node metastasis from a clinical perspective.

7. Targeting Lymph Node Metastases

Controlling the size of lymph node metastasis is important since recent clinical data have shown that breast cancer patients with micrometastases (≤2 mm) in their SLNs have a reduced incidence of distant metastasis compared to those with macrometastasis [95]. Angiogenesis is required for invasive tumor growth and metastasis of the primary tumor [96]. We, and others have previously shown that antiangiogenic therapy was not as effective in stopping the initial seeding of tumor cells in the lymph node when compared to anti-lymphangiogenic therapy [11, 61, 97]. Furthermore, anti angiogenic therapy failed to inhibit growth of tumors in the lymph nodes [50], in contrast to studies where antiangiogenesis inhibitors eradicate or slow the growth of the primary tumor. Thus, treatment response in the primary tumors may not predict the response of lymph node metastases.

In patients with locally advanced breast cancer, a significant fraction of patients had residual lymph node metastases after neoadjuvant therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide, had eliminated disease in primary tumor [98, 99]. Radiotherapy has shown to be effective against such residual tumor foci in loco-regional tissue. In a meta-analysis of breast cancer patients, women with as few as 1–3 positive lymph nodes were shown to benefit from radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary dissection [100]. However, lymph node metastases can travel beyond the sentinel and axillary lymph nodes [101]. For example, internal mammary lymph nodes (IMN) are associated with breast cancer positive axillary lymph nodes but are usually not irradiated due to cardiac toxicity. However, IMN metastases are found in at least 10% of patients where the axillary lymph nodes are negative. Overall survival and cancer-specific survival were increased in a large cohort of node negative breast cancer patients [102] that received IMN irradiation. It was found that melanoma patients with non-SLN metastases were three times more likely to die compared with patients where the metastasis was limited to the SLN [103]. Since it may be unclear as to which lymph nodes should be irradiated and whether they are accessible, such patients may benefit from therapeutic options that include radiation and a systemic chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy that will eradicate occult cancer cells in all lymph nodes.

Several reports have shown that subcutaneous chemotherapy targeting regional lymphatic tissues provides greater drug concentration in the lymph node compared to intravenous delivery [104]. It is unknown whether subcutaneous administration will lead to lower rates of residual tumor in the lymph node. However, by intravenous route, drug delivery to the lymph nodes of HIV+ patients has been shown to achieve lower concentrations than that found in the blood and other organs, which correlated with increased viral replication in the lymph node compared to blood [105]. Recent approaches have focused on improving drug exposure, retention, and distribution within the lymphatic system. Using lipid nanoparticles, the concentration of anti-retroviral drug was significantly increased in lymph nodes throughout a primate compared to standard oral formulations [106]. Such approaches will likely also enhance the targeting of tumor cells in the lymph node.

There is therapeutic potential in reversing tumor-induced immune suppression by targeting “metastatic niche” molecules. This strategy may prevent the spread of cancer to distant lymph nodes and/or organs. Taking advantage of the tumor antigens that are present in SLNs, Thomas et al. used nanoparticles to deliver adjuvant to SLN to enhance immune activation. This approach led to decreased tumor growth by altering the dendritic cell profile and increasing Th1 immunity within the tumor [107]. GM-CSF, a multifunctional cytokine, is necessary to induce expansion of a population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells that lead to tolerance in secondary lymphoid organs. Blocking GM-CSF reduced tumor-induced tolerance by enhancing tumor specific, IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes in lymph nodes [33]. Likewise, inhibition of TGF-β from the primary tumor decreased the number of regulatory T cells and increased the number of tumor antigen-specific helper and cytotoxic T cells that produced IFN-γ [108]. This approach led to diminished growth of distant metastases. Further approaches to stimulate the immune system to target lymph node metastasis are under development.

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Studies focused on understanding the process of lymphatic metastases and the role of the lymph node in tumor progression in the past decade have given us insights into the importance of these organs in cancer biology. Metastasis to the lymph node is preceded by changes in the lymph node microenvironment. A more comprehensive understanding of the molecular signals in the premetastatic lymph node niche that facilitate tumor metastasis could provide therapeutic targets to control lymph node metastasis. Although several advances have been made in the field of lymphatic metastasis, unanswered questions regarding the effects of the lymph node microenvironment on the metastatic potential of tumor cells in the lymph node or on anti-tumor immune response still remain. The ability of metastatic tumor cells in the lymph node to progress to distant sites remains controversial and we lack biomarkers to identify patients at risk of systemic spread from lymph node metastases. With continued research progress to address these issues, we will improve treatment and outcomes for patients with lymphatic metastasis.

Highlights.

Lymphatic endothelial cells and vessels actively participate in tumor cell metastasis

The premetastatic lymph node expresses immunosuppressive signals that condition this organ for the arrival of tumor cells

The composition of a metastatic lymph node undergoes remodeling that impacts the growth of cancer cells

Tumor lesions in the lymph node are polyclonal and mostly represent the genetic composition of the primary tumor

The ability of tumor cells residing in the lymph node to colonize distant organs is controversial

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health DP2OD008780 (TPP), R00CA137167 (TPP), R21AI097745 (TPP), National Cancer Institute Federal Share/MGH Proton Beam Income on C06 CA059267 (TPP), UNCF-Merck Science Initiative Postdoctoral Fellowship (DJ) and Burroughs Wellcome Postdoctoral Enrichment Program Award (DJ). We would like to acknowledge Sonia Pereira for her help with the graphical illustration.

Abbreviations

- ALND

Axillary Lymph Node Dissection

- BMP-4

bone morphogenetic protein-4

- DC

Dendritic cell

- EPO

erythropoietin

- HEVs

high endothelial venules

- IFN-γ

interferon γ

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- IMN

internal mammary lymph nodes

- LEC

Lymphatic endothelial cell

- LYVE-1

lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cells, PGE2, prostaglandin E2

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- PNAd

peripheral node addressin

- SDF-1α

stromal derived factor-1α

- SCS

sub-capsular sinus

- SLN

Sentinel Lymph Node

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- Treg

regulatory T cells

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fidler IJ. Critical determinants of metastasis. Seminars in cancer biology. 2002;12:89–96. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podgrabinska S, Skobe M. Role of lymphatic vasculature in regional and distant metastases. Microvascular research. 2014;95C:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawada K, Taketo MM. Significance and mechanism of lymph node metastasis in cancer progression. Cancer research. 2011;71:1214–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Annals of surgical oncology. 2010;17:1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathanson SD, Shah R, Rosso K. Sentinel lymph node metasatses in cancer: causes, detection and their role in disease progression. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cady B. Regional lymph node metastases; a singular manifestation of the process of clinical metastases in cancer: contemporary animal research and clinical reports suggest unifying concepts. Annals of surgical oncology. 2007;14:1790–800. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–6. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swartz MA. Immunomodulatory roles of lymphatic vessels in cancer progression. Cancer immunology research. 2014;2:701–7. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padera TP, Kadambi A, di Tomaso E, Carreira CM, Brown EB, Boucher Y, et al. Lymphatic metastasis in the absence of functional intratumor lymphatics. Science. 2002;296:1883–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1071420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padera TP, Stoll BR, So PT, Jain RK. Conventional and high-speed intravital multiphoton laser scanning microscopy of microvasculature, lymphatics, and leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Molecular imaging. 2002;1:9–15. doi: 10.1162/15353500200200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshida T, Isaka N, Hagendoorn J, di Tomaso E, Chen YL, Pytowski B, et al. Imaging steps of lymphatic metastasis reveals that vascular endothelial growth factor-C increases metastasis by increasing delivery of cancer cells to lymph nodes: therapeutic implications. Cancer research. 2006;66:8065–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakoc BJ, Lanning RM, Tyrrell JA, Padera TP, Bartlett LA, Stylianopoulos T, et al. Three-dimensional microscopy of the tumor microenvironment in vivo using optical frequency domain imaging. Nature medicine. 2009;15:1219–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao S, Cheng G, Conner DA, Huang Y, Kucherlapati RS, Munn LL, et al. Impaired lymphatic contraction associated with immunosuppression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:18784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116152108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proulx ST, Luciani P, Christiansen A, Karaman S, Blum KS, Rinderknecht M, et al. Use of a PEG-conjugated bright near-infrared dye for functional imaging of rerouting of tumor lymphatic drainage after sentinel lymph node metastasis. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sevick-Muraca EM, Kwon S, Rasmussen JC. Emerging lymphatic imaging technologies for mouse and man. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:905–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI71612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alitalo K. The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nature medicine. 2011;17:1371–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stacker SA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Fox SB, Achen MG. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic vessel remodelling in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2014;14:159–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiological reviews. 1990;70:987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruddle NH. Lymphatic vessels and tertiary lymphoid organs. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:953–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI71611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peinado H, Lavotshkin S, Lyden D. The secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation: old sayings and new thoughts. Seminars in cancer biology. 2011;21:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paget S. The Distribution of Secondary Growths in Cancer of the Breast. The Lancet. 1889;133:571–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrell MI, Iritani BM, Ruddell A. Tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis and increased lymph flow precede melanoma metastasis. The American journal of pathology. 2007;170:774–86. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung MK, Do IG, Jung E, Son YI, Jeong HS, Baek CH. Lymphatic vessels and high endothelial venules are increased in the sentinel lymph nodes of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma before the arrival of tumor cells. Annals of surgical oncology. 2012;19:1595–601. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian CN, Berghuis B, Tsarfaty G, Bruch M, Kort EJ, Ditlev J, et al. Preparing the “soil”: the primary tumor induces vasculature reorganization in the sentinel lymph node before the arrival of metastatic cancer cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:10365–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa F, Amano H, Eshima K, Ito Y, Matsui Y, Hosono K, et al. Prostanoid induces premetastatic niche in regional lymph nodes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014 doi: 10.1172/JCI73530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian CN, Resau JH, Teh BT. Prospects for vasculature reorganization in sentinel lymph nodes. Cell cycle. 2007;6:514–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohrt HE, Nouri N, Nowels K, Johnson D, Holmes S, Lee PP. Profile of immune cells in axillary lymph nodes predicts disease-free survival in breast cancer. PLoS medicine. 2005;2:e284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van den Eynden GG, Van der Auwera I, Van Laere SJ, Colpaert CG, Turley H, Harris AL, et al. Angiogenesis and hypoxia in lymph node metastases is predicted by the angiogenesis and hypoxia in the primary tumour in patients with breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 2005;93:1128–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Torisu-Itakara H, Cochran AJ, Kadison A, Huynh Y, Morton DL, et al. Quantitative analysis of melanoma-induced cytokine-mediated immunosuppression in melanoma sentinel nodes. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leong SP, Peng M, Zhou YM, Vaquerano JE, Chang JW. Cytokine profiles of sentinel lymph nodes draining the primary melanoma. Annals of surgical oncology. 2002;9:82–7. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poindexter NJ, Sahin A, Hunt KK, Grimm EA. Analysis of dendritic cells in tumor-free and tumor-containing sentinel lymph nodes from patients with breast cancer. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2004;6:R408–15. doi: 10.1186/bcr808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alb M, Sie C, Adam C, Chen S, Becker JC, Schrama D. Cellular and cytokine-dependent immunosuppressive mechanisms of grm1-transgenic murine melanoma. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2012;61:2239–49. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, Marigo I, Fernandez Gomez A, Mesa C, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. European journal of immunology. 2010;40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Zhang C, Li W, Deng J, Herrmann A, Priceman SJ, et al. CD8 T-cell immunosurveillance constrains lymphoid pre-metastatic myeloid cell accumulation. European journal of immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eji.201444467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirakawa S, Kodama S, Kunstfeld R, Kajiya K, Brown LF, Detmar M. VEGF-A induces tumor and sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis and promotes lymphatic metastasis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:1089–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirakawa S, Brown LF, Kodama S, Paavonen K, Alitalo K, Detmar M. VEGF-C-induced lymphangiogenesis in sentinel lymph nodes promotes tumor metastasis to distant sites. Blood. 2007;109:1010–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garmy-Susini B, Avraamides CJ, Desgrosellier JS, Schmid MC, Foubert P, Ellies LG, et al. PI3Kalpha activates integrin alpha4beta1 to establish a metastatic niche in lymph nodes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:9042–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219603110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AS, Kim DH, Lee JE, Jung YJ, Kang KP, Lee S, et al. Erythropoietin induces lymph node lymphangiogenesis and lymph node tumor metastasis. Cancer research. 2011;71:4506–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farnsworth RH, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Matsumoto M, Nowell CJ, Achen MG, et al. A role for bone morphogenetic protein-4 in lymph node vascular remodeling and primary tumor growth. Cancer research. 2011;71:6547–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carriere V, Colisson R, Jiguet-Jiglaire C, Bellard E, Bouche G, Al Saati T, et al. Cancer cells regulate lymphocyte recruitment and leukocyte-endothelium interactions in the tumor-draining lymph node. Cancer research. 2005;65:11639–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, et al. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer cell. 2012;21:642–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields JD, Borsetti M, Rigby H, Harper SJ, Mortimer PS, Levick JR, et al. Lymphatic density and metastatic spread in human malignant melanoma. British journal of cancer. 2004;90:693–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karpanen T, Egeblad M, Karkkainen MJ, Kubo H, Yla-Herttuala S, Jaattela M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C promotes tumor lymphangiogenesis and intralymphatic tumor growth. Cancer research. 2001;61:1786–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo R, Janes L, Velasco P, et al. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nature medicine. 2001;7:192–8. doi: 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandriota SJ, Jussila L, Jeltsch M, Compagni A, Baetens D, Prevo R, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C-mediated lymphangiogenesis promotes tumour metastasis. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:672–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stacker SA, Caesar C, Baldwin ME, Thornton GE, Williams RA, Prevo R, et al. VEGF-D promotes the metastatic spread of tumor cells via the lymphatics. Nature medicine. 2001;7:186–91. doi: 10.1038/84635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Issa A, Le TX, Shoushtari AN, Shields JD, Swartz MA. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C and C-C chemokine receptor 7 in tumor cell-lymphatic cross-talk promote invasive phenotype. Cancer research. 2009;69:349–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng W, Aspelund A, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenic factors, mechanisms, and applications. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:878–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI71603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karnezis T, Shayan R, Caesar C, Roufail S, Harris NC, Ardipradja K, et al. VEGF-D promotes tumor metastasis by regulating prostaglandins produced by the collecting lymphatic endothelium. Cancer cell. 2012;21:181–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Padera TP, Kuo AH, Hoshida T, Liao S, Lobo J, Kozak KR, et al. Differential response of primary tumor versus lymphatic metastasis to VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 kinase inhibitors cediranib and vandetanib. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2008;7:2272–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gogineni A, Caunt M, Crow A, Lee CV, Fuh G, van Bruggen N, et al. Inhibition of VEGF-C modulates distal lymphatic remodeling and secondary metastasis. PloS one. 2013;8:e68755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tammela T, Saaristo A, Holopainen T, Yla-Herttuala S, Andersson LC, Virolainen S, et al. Photodynamic ablation of lymphatic vessels and intralymphatic cancer cells prevents metastasis. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:69ra11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Escobar-Prieto A, Gonzalez G, Templeton AW, Cooper BR, Palacios E. Lymphatic channel obstruction. Patterns of altered flow dynamics. The American journal of roentgenology, radium therapy, and nuclear medicine. 1971;113:366–75. doi: 10.2214/ajr.113.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nathanson SD, Shah R, Chitale DA, Mahan M. Intraoperative clinical assessment and pressure measurements of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014;21:81–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwon S, Agollah GD, Wu G, Sevick-Muraca EM. Spatio-Temporal Changes of Lymphatic Contractility and Drainage Patterns following Lymphadenectomy in Mice. PloS one. 2014;9:e106034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barankay T, Baumgartl H, Lubbers DW, Seidl E. Oxygen pressure in small lymphatics. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 1976;366:53–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02486560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samet A, Gilbey P, Talmon Y, Cohen H. Vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2001;115:760–2. doi: 10.1258/0022215011908892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chovatiya R, Medzhitov R. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Molecular cell. 2014;54:281–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–5. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fukumura D, Xavier R, Sugiura T, Chen Y, Park EC, Lu N, et al. Tumor induction of VEGF promoter activity in stromal cells. Cell. 1998;94:715–25. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts N, Kloos B, Cassella M, Podgrabinska S, Persaud K, Wu Y, et al. Inhibition of VEGFR-3 activation with the antagonistic antibody more potently suppresses lymph node and distant metastases than inactivation of VEGFR-2. Cancer research. 2006;66:2650–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arapandoni-Dadioti P, Giatromanolaki A, Trihia H, Harris AL, Koukourakis MI. Angiogenesis in ductal breast carcinoma. Comparison of microvessel density between primary tumour and lymph node metastasis. Cancer letters. 1999;137:145–50. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naresh KN, Nerurkar AY, Borges AM. Angiogenesis is redundant for tumour growth in lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 2001;38:466–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sonveaux P, Vegran F, Schroeder T, Wergin MC, Verrax J, Rabbani ZN, et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3930–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI36843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guillaumond F, Leca J, Olivares O, Lavaut MN, Vidal N, Berthezene P, et al. Strengthened glycolysis under hypoxia supports tumor symbiosis and hexosamine biosynthesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:3919–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219555110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koshikawa N, Iyozumi A, Gassmann M, Takenaga K. Constitutive upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha mRNA occurring in highly metastatic lung carcinoma cells leads to vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression upon hypoxic exposure. Oncogene. 2003;22:6717–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Das S, Sarrou E, Podgrabinska S, Cassella M, Mungamuri SK, Feirt N, et al. Tumor cell entry into the lymph node is controlled by CCL1 chemokine expressed by lymph node lymphatic sinuses. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1509–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiley HE, Gonzalez EB, Maki W, Wu MT, Hwang ST. Expression of CC chemokine receptor-7 and regional lymph node metastasis of B16 murine melanoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93:1638–43. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.21.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ding Y, Shimada Y, Maeda M, Kawabe A, Kaganoi J, Komoto I, et al. Association of CC chemokine receptor 7 with lymph node metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:3406–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cochran AJ, Huang RR, Lee J, Itakura E, Leong SP, Essner R. Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nature reviews Immunology. 2006;6:659–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nature reviews Immunology. 2003;3:867–78. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ito M, Minamiya Y, Kawai H, Saito S, Saito H, Nakagawa T, et al. Tumor-derived TGFbeta-1 induces dendritic cell apoptosis in the sentinel lymph node. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:5637–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang RR, Wen DR, Guo J, Giuliano AE, Nguyen M, Offodile R, et al. Selective Modulation of Paracortical Dendritic Cells and T-Lymphocytes in Breast Cancer Sentinel Lymph Nodes. The breast journal. 2000;6:225–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.98114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watanabe S, Deguchi K, Zheng R, Tamai H, Wang LX, Cohen PA, et al. Tumor-induced CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells suppress T cell sensitization in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:3291–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Podgrabinska S, Kamalu O, Mayer L, Shimaoka M, Snoeck H, Randolph GJ, et al. Inflamed lymphatic endothelium suppresses dendritic cell maturation and function via Mac-1/ICAM-1-dependent mechanism. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:1767–79. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Rouhani SJ, Guidi CJ, Qiao H, Fahl SP, et al. Lymphatic endothelial cells induce tolerance via PD-L1 and lack of costimulation leading to high-level PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells. Blood. 2012;120:4772–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-427013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lund AW, Duraes FV, Hirosue S, Raghavan VR, Nembrini C, Thomas SN, et al. VEGF-C promotes immune tolerance in B16 melanomas and cross-presentation of tumor antigen by lymph node lymphatics. Cell reports. 2012;1:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Preynat-Seauve O, Contassot E, Schuler P, Piguet V, French LE, Huard B. Extralymphatic tumors prepare draining lymph nodes to invasion via a T-cell cross-tolerance process. Cancer research. 2007;67:5009–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Current opinion in immunology. 2012;24:207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deng L, Zhang H, Luan Y, Zhang J, Xing Q, Dong S, et al. Accumulation of foxp3+ T regulatory cells in draining lymph nodes correlates with disease progression and immune suppression in colorectal cancer patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:4105–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zippelius A, Batard P, Rubio-Godoy V, Bioley G, Lienard D, Lejeune F, et al. Effector function of human tumor-specific CD8 T cells in melanoma lesions: a state of local functional tolerance. Cancer research. 2004;64:2865–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hargadon KM, Brinkman CC, Sheasley-O’neill SL, Nichols LA, Bullock TN, Engelhard VH. Incomplete differentiation of antigen-specific CD8 T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:6081–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruddell A, Harrell MI, Furuya M, Kirschbaum SB, Iritani BM. B lymphocytes promote lymphogenous metastasis of lymphoma and melanoma. Neoplasia. 2011;13:748–57. doi: 10.1593/neo.11756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li Q, Grover AC, Donald EJ, Carr A, Yu J, Whitfield J, et al. Simultaneous targeting of CD3 on T cells and CD40 on B or dendritic cells augments the antitumor reactivity of tumor-primed lymph node cells. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:1424–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li Q, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Donald EJ, Li M, Chang AE. In vivo sensitized and in vitro activated B cells mediate tumor regression in cancer adoptive immunotherapy. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:3195–203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zirakzadeh AA, Marits P, Sherif A, Winqvist O. Multiplex B cell characterization in blood, lymph nodes, and tumors from patients with malignancies. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:5847–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li Q, Lao X, Pan Q, Ning N, Yet J, Xu Y, et al. Adoptive transfer of tumor reactive B cells confers host T-cell immunity and tumor regression. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:4987–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McFadden DG, Papagiannakopoulos T, Taylor-Weiner A, Stewart C, Carter SL, Cibulskis K, et al. Genetic and clonal dissection of murine small cell lung carcinoma progression by genome sequencing. Cell. 2014;156:1298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Naxerova K, Brachtel E, Salk JJ, Seese AM, Power K, Abbasi B, et al. Hypermutable DNA chronicles the evolution of human colon cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:E1889–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400179111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hack TF, Cohen L, Katz J, Robson LS, Goss P. Physical and psychological morbidity after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:143–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2011;305:569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Straver ME, Meijnen P, van Tienhoven G, van de Velde CJ, Mansel RE, Bogaerts J, et al. Role of axillary clearance after a tumor-positive sentinel node in the administration of adjuvant therapy in early breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:731–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rutgers EJ, Donker M, Straver ME, Meijnen P, Van De Velde CJH, Mansel RE, Westenberg H, Orzalesi L, Bouma WH, van der Mijle H, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Veltkamp SC, Slaets L, Messina CGM, Duez NJ, Hurkmans C, Bogaerts J, van Tienhoven G. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer patients: Final analysis of the EORTC AMAROS trial (10981/22023) J Clin Oncol. 2013;(suppl):abstr LBA1001. LBA1001. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, Zurrida S, Luini A, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Annals of surgery. 2010;251:595–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Seminars in oncology. 2002;29:15–8. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matsumoto M, Roufail S, Inder R, Caesar C, Karnezis T, Shayan R, et al. Signaling for lymphangiogenesis via VEGFR-3 is required for the early events of metastasis. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 2013;30:819–32. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9581-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuerer HM, Newman LA, Smith TL, Ames FC, Hunt KK, Dhingra K, et al. Clinical course of breast cancer patients with complete pathologic primary tumor and axillary lymph node response to doxorubicin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:460–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cox C, Holloway CM, Shaheta A, Nofech-Mozes S, Wright FC. What is the burden of axillary disease after neoadjuvant therapy in women with locally advanced breast cancer? Current oncology. 2013;20:111–7. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ebctcg, McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, Cutter D, Duane F, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:2127–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huston TL, Pressman PI, Moore A, Vahdat L, Hoda SA, Kato M, et al. The presentation of contralateral axillary lymph node metastases from breast carcinoma: a clinical management dilemma. The breast journal. 2007;13:158–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Courdi A, Chamorey E, Ferrero JM, Hannoun-Levi JM. Influence of internal mammary node irradiation on long-term outcome and contralateral breast cancer incidence in node-negative breast cancer patients. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2013;108:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pasquali S, Mocellin S, Mozzillo N, Maurichi A, Quaglino P, Borgognoni L, et al. Nonsentinel lymph node status in patients with cutaneous melanoma: results from a multi-institution prognostic study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:935–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu F, Tamhane M, Morris ME. Pharmacokinetics, lymph node uptake, and mechanistic PK model of near-infrared dye-labeled bevacizumab after IV and SC administration in mice. The AAPS journal. 2012;14:252–61. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fletcher CV, Staskus K, Wietgrefe SW, Rothenberger M, Reilly C, Chipman JG, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication is associated with lower antiretroviral drug concentrations in lymphatic tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:2307–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318249111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Freeling JP, Ho RJ. Anti-HIV drug particles may overcome lymphatic drug insufficiency and associated HIV persistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:E2512–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406554111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thomas SN, Vokali E, Lund AW, Hubbell JA, Swartz MA. Targeting the tumor-draining lymph node with adjuvanted nanoparticles reshapes the anti-tumor immune response. Biomaterials. 2014;35:814–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fujita T, Teramoto K, Ozaki Y, Hanaoka J, Tezuka N, Itoh Y, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta-mediated immunosuppression in tumor-draining lymph nodes augments antitumor responses by various immunologic cell types. Cancer research. 2009;69:5142–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]