Abstract

Objective

P-selectin is a cellular adhesion molecule that has been shown to be crucial in development of coronary heart disease (CHD). We sought to determine the role of P-selectin on the risk of atherosclerosis in a large multi-ethnic population.

Methods

Data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), including 1628 African, 702 Chinese, 2393 non-Hispanic white, and 1302 Hispanic Americans, were used to investigate the association of plasma P-selectin with CHD risk factors, coronary artery calcium (CAC), intima-media thickness, and CHD. Regression models were used to investigate the association between P-selectin and risk factors, Tobit model for CAC, and Cox regression for CHD events.

Results

Mean levels of P-selectin differed by ethnicity and were higher in men (P < 0.001). For all ethnic groups, P-selectin was positively associated with measures of adiposity, blood pressure, current smoking, LDL, and triglycerides and inversely with HDL. A significant ethnic interaction was observed for the association of P-selectin and prevalent diabetes; however, P-selectin was positively associated with HbA1c in all groups. Higher P-selectin levels were associated with greater prevalence of CAC. Over 10.1 years of follow-up, there were 335 incident CHD events. There was a positive linear association between P-selectin levels and rate of incident CHD after adjustment for traditional risk factors. However, association was only significant in non-Hispanic white Americans (HR: 1.81, 95% CI 1.07 to 3.07, P = 0.027).

Conclusion

We observed ethnic heterogeneity in the association of P-selectin and risk of CHD.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular risk factors, Coronary artery calcium, P-selectin

1. Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death for both men and women in every major race/ethnic group in America [1]. Furthermore, effective secondary treatment of CHD requires enormous health care expenditures, justifying continued efforts to identify the determinants of early disease. The cellular adhesion pathway plays a crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis but many potentially important adhesion proteins have yet to be fully studied in diverse populations. Selectins are one of the four main families of adhesion molecules. Found in alpha-granules of platelets [2] and Weibel-Palade bodies [3,4] of endothelial cells, P-selectin is a cellular adhesion molecule that enhances procoagulant activity [5] and activation of leukocyte integrins [6]. Platelets are the major source for P-selectin and the soluble form is a biomarker of platelet and endothelial activation [7,8]. Given the role of P-selectin, it has been postulated that higher levels of this protein may be an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic disease.

Evidence from animal models suggests that circulating levels are a risk factor of atherosclerosis [9]. For example, disruption of the ligand for P-selectin (PSGL-1) in animal models reduced atherosclerosis [10,11] and genetically engineered mouse models with abnormally high P-selectin levels had increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis [9]. In humans, associations of plasma P-selectin with cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been reported in predominantly European ancestry populations. The Women’s Health Study, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial, and Risk of Arterial Thrombosis in Relation to Oral Contraceptives Study all reported that higher plasma P-selectin levels were associated with development of myocardial infarction (MI) [12-14].

The relationship of P-selectin levels and cardiovascular risk factors is less clear. The Framingham Heart Offspring Study reported significant positive correlations of plasma P-selectin and age, sex, current smoking, body mass index, waist, blood pressure, fasting glucose and diabetes, HDL, triglycerides, and hormone replacement therapy use in women [15]. Results from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study largely confirmed these correlations in both African and European Americans with the exceptions of null associations observed with age and HDL in both ethnic groups and an ethnic-specific association of LDL and P-selectin observed only in European Americans [16]. However, results from the Fels Longitudinal Study reported the associations with cholesterol and smoking were only significant in women and the other traditional risk factors were unrelated to levels of P-selectin [17].

The relationship of plasma P-selectin and clinical events, subclinical disease, and cardiovascular risk factors has not been fully elucidated. Furthermore, assessment of these relationships in diverse populations is lacking. Therefore, the study detailed herein uses data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) in four race/ethnic populations to test the hypothesis that plasma P-selectin is positively associated with subclinical atherosclerosis and incident CHD, independent of traditional CVD risk factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) enrolled 6814 participants from 2000-2002 without existing clinical CVD who were aged 45–84 years. This study population included 38% non-Hispanic white, 28% African, 22% Hispanic, and 12% Chinese Americans.

MESA participants were examined at six field centers located in Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Forsyth County, NC; Los Angeles County, CA; Northern Manhattan, NY and Saint Paul, MN. MESA and its ancillary studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at participating centers and all participants gave written informed consent. The MESA study has been described in detail elsewhere [18]. Under the auspices of the Multi-Scale Biology of Atherosclerosis in the Cellular Adhesion Pathway (HL98077 – MESA Adhesion Study), 6148 MESA participants had plasma P-selectin measured at exam 2. We excluded a total of 123 samples, 2 Chinese and 3 Hispanic Americans from field centers that did not actively recruit these two ethnic groups, 77 participants with CVD events prior to exam 2, 40 subjects with outlying plasma P-selectin levels, and 1 subject who did not complete exam 2 or subsequent exams due to cognitive impairment - for a final sample size of 6025 participants including 1628 African, 702 Chinese, 2393 non-Hispanic white, and 1302 Hispanic Americans.

2.2. Measurements

Height was measured while participants were standing without shoes, heels together against a vertical mounted ruler. All other measures were obtained at exam 2. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Hip and waist circumferences were measured at the maximal protrusion of the hips and at the level of the umbilicus with the participant standing erect. A combination of self-administered and interview-administered questionnaires was used to collect data such as smoking history, alcohol intake, and medication use. Resting seated blood pressure was measured three times using an automated oscillometric method (Dinamap) and the average of the second and third readings are used in analyses. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mm Hg, or taking antihypertensive medication. In those with hypertension, we defined controlled hypertension as a SBP <140 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg. Uncontrolled hypertension was defined as a SBP ≥140 mm Hg or a DBP ≥90 mm Hg. Diabetes was defined as any participant who self-reported a physician diagnosis, used diabetic medication, had a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, or a non-fasting glucose of ≥200 mg/dL.

Serum glucose was assayed by a hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method, and triglycerides and cholesterol were assayed by enzymatic methods. HDL cholesterol was measured after precipitation of non-HDL-cholesterol with magnesium/dextran and LDL was calculated via the Freidewald equation. Hemoglobin A1c was assayed using an automated high performance liquid chromatography methods (Tosoh HPLC Glycohemoglobin Analyzer).

sP-selectin was measured in plasma by a quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the Human Soluble P-selectin/CD62P Immunoassay Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Two independent groups of samples were assayed. A different lot of ELISA reagent and different human control pool was used for each group. The inter-assay CV for group 1 was 6.7% at a control concentration of 182 mg/dL; the inter-assay CV for group 2 was 9.7% at a control concentration of 79 mg/dL. The minimum detectable level was 0.5 ng/mL for both assay groups.

Computed tomography of the coronary arteries was performed and has been previously described [19]. In brief, at three of six clinical centers, electron beam scanners (Imatron C-150; Imatron, Inc., San Francisco, CA) were used with cardiac-gating at 80% of the R-R interval. At the other three centers, a prospective electrocardiogram-triggered multi-detector scan was acquired at 50% of the R-R interval. All scanners were comparable in their ability to measure calcium [19]. Scans were read centrally at Harbor-University of California Medical Center (Los Angeles, CA), and Agatston coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores were quantified by blinded CT image analysts. CAC was measured on all eligible participants at exam 1, on a random set of 50% at exam 2, and on the other 50% at exam 3. Common carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) was performed and has been previously described [20]. Far wall common carotid artery IMT was measured at baseline and then on a random set of 50% of participants at exam 2 and in the other random set at exam 3. Trained readers traced the key two interfaces of the far wall to obtain manual tracings which were used to calculate mean IMT.

2.3. Cardiovascular events

Complete details of event ascertainment have been summarized previously [21] and the MESA website exam and follow-up forms for ascertaining events are available on the MESA website (http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org). In brief, the cohort was followed for 10 years via telephone interviews at 9–12 month intervals of participants or next of kin for out of hospital deaths. Hospital records were obtained on an estimated 99% of hospitalized CVD events and some information on 97% of outpatient diagnostic encounters. Trained personnel abstracted any hospital records suggesting possible CVD event that included MI, angina, resuscitated cardiac arrest, stroke (not transient ischemic attack), CHD, or other CVD death. MI was defined by integrating cardiac pain, biomarker level, and ECG changes using the Minnesota code [22]. For these analyses, we focused on incident CHD events that include all MI, resuscitated cardiac arrest, angina, and CHD death cases during follow-up.

2.4. Statistical analysis

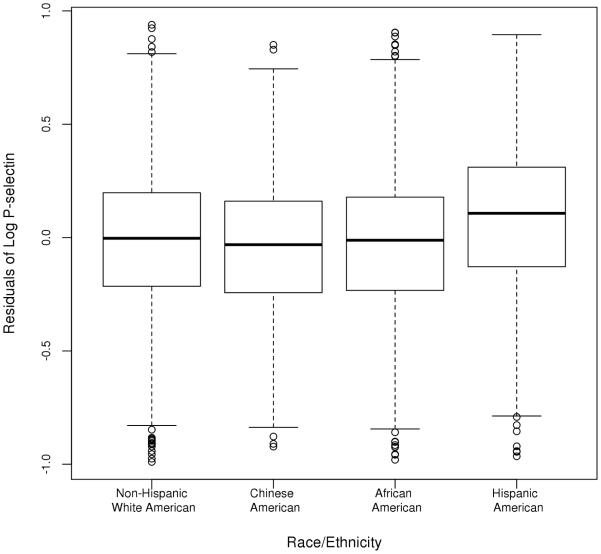

The log-transformed P-selectin distribution for each group was assessed and outliers were removed as appropriate (n = 40). To address differences in P-selectin levels across groups, we obtained residuals from a linear regression model using log-transformed raw P-selectin values as a response and group as a predictor (Supplemental Fig. 1). All references of P-selectin levels heretofore refer to these residual values. Baseline characteristics were compared across race/ethnic strata using regression models. Linear regression models were also used to explore the association of P-selectin levels and traditional CVD risk factors in sex and ethnic strata, with P-selectin as the response and CVD risk factors as predictors. Traditional CVD risk factors included age, sex, body mass index, smoking and alcohol use, total and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and hypertension and diabetes status. Sex by risk factor and race/ethnicity by risk factor interactions were included as appropriate. To simplify the presentation of results, risk factor levels across quintiles of P-selectin are reported.

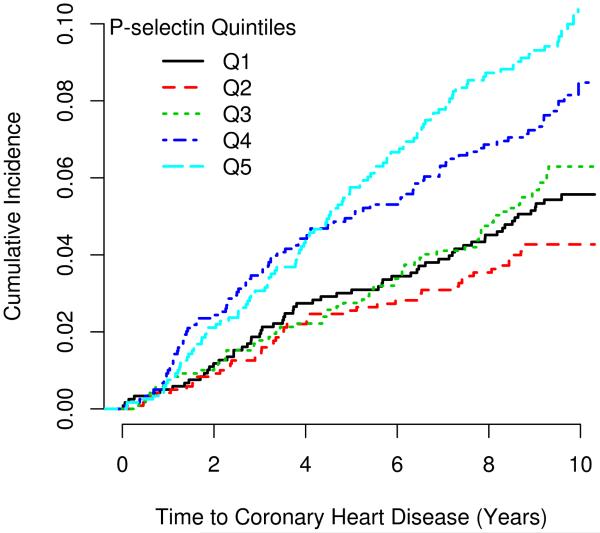

To investigate the association of P-selectin levels and subclinical atherosclerosis, CAC (exam 2 and 3) and IMT (exam 2 and 3), appropriate regression models were fit with P-selectin as the independent variable with adjustment for traditional risk factors. Race/ethnicity was included as a covariate for all pooled analyses. Assumptions of linearity for each were evaluated using generalized additive models with cubic B-splines. There were no indications of major departures from linearity. Because the distribution of CAC has a large percentage of zero measurements, standard normalization transformations are not adequate; therefore, the Tobit model was used to investigate the relationship between CAC and P-selectin concentration levels [23,24]. The Tobit model is a form of linear regression that treats the outcome measure as a latent variable comprised of both a discrete and continuous component. The outcome measure equals the latent variable whenever the latent variable is above zero, and zero otherwise. The association of P-selectin with time to CHD was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusting for traditional risk factors. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate cumulative incidence curves by P-selectin quintiles. Statistical significance for association of P-selectin with any outcome was determined at a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.05 (0.05/3 outcomes = 0.017).

3. Results

3.1. Plasma P-selectin and CVD risk factors

Significant race/ethnic differences were observed for clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis, as well as all traditional CVD risk factors except sex and LDL cholesterol (Table 1), with no systematic differences by group (Supplemental Table 2). There were differences in plasma P-selectin levels by race/ethnicity (Figure 1) and mean levels were higher in men compared to women in all race/ethnic groups (P < 0.001). However, there were no systematic differences in P-selectin levels by age. Specific associations between plasma P-selectin level and traditional CVD risk factors are summarized in Table 2 across quintiles of P-selectin with race/ethnic stratified results summarized in Supplemental Table 2. In summary, of the CVD risk factors, P-selectin was positively associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes, total and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and current smoking and negatively associated with HDL cholesterol. Of the antiplatelet medications, only aspirin use was common, with 30% of the MESA cohort reporting taking aspirin at least 3 days per week. However, there were no differences in P-selectin levels by aspirin use (P = 0.89).

Table 1.

MESA characteristics by race/ethnicity measured at exam 2 unless otherwise indicated (mean ± standard deviation or percent).

| Characteristics | Non-Hispanic White American |

Chinese American |

African American |

Hispanic American |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2383 | 700 | 1631 | 1303 | |

| P-selectin residuals | −0.02 (0.31) | −0.04 (0.30) | −0.03 (0.31) | 0.09 (0.31) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | 64 (10.1) | 63 (10.1) | 64 (9.9) | 63 (10.2) | 0.0008 |

| Sex, % female | 51 | 51 | 55 | 52 | 0.12 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.8 (5.0) | 24.1 (3.3) | 30.2 (5.8) | 29.6 (5.3) | <0.0001 |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 121 (19) | 121 (21) | 130 (21) | 125 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 69 (9.6) | 69 (9.8) | 74 (10.2) | 70 (10.1) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, % yes | 38 | 37 | 61 | 43 | <0.0001 |

| Antihypertensive therapy, % yes | 38 | 33 | 54 | 37 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % yes | 8 | 14 | 19 | 20 | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.4 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.9) | 5.9 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 193 (36) | 190 (32) | 188 (37) | 194 (36) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 53 (16) | 50 (13) | 54 (15) | 49 (14) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 114 (32) | 111 (29) | 114 (34) | 115 (32) | 0.14 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 131 (76) | 149 (93) | 107 (68) | 155 (94) | <0.0001 |

| Any antilipidemic therapy, % Yes | 26 | 20 | 20 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| Statin use, % yes | 24 | 18 | 19 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker, % yes | 10 | 5 | 16 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| Current use of alcohol, % yes | 68 | 31 | 45 | 41 | <0.0001 |

| Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) | |||||

| Participants measured at exam 2 or 3, n | 2187 | 654 | 1477 | 1171 | |

| CAC > 0, % Yes | 62 | 53 | 49 | 53 | <0.0001 |

| CAC, Agatston units | 245 (559) | 139 (385) | 141 (434) | 164 (468) | <0.0001 |

| Right Common Carotid Intima-medial Thickness (IMT) | |||||

| Participants measured at exam 2 or 3, n | 2134 | 656 | 1413 | 1155 | |

| IMT, mm | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| CHD events through 2012, n (%) | 173 (7.3%) | 32 (4.6%) | 97 (5.9%) | 83 (6.4%) | 0.059 |

P-value from regression model comparing variables across ethnic groups.

Fig. 1.

Box plots of the residuals of the log of P-selectin by race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular risk factor levels across quintiles of circulating P-selectin residual (mean ± standard deviation or percent).

| P-selectin categories |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P-valuea | Race interaction P-value |

| P-selectin residual range | −0.99, −0.26 | −0.26, −0.07 | −0.07, 0.09 | 0.09, 0.26 | 0.26, 0.94 | |||

| n | 6017 | 1203 | 1204 | 1204 | 1202 | 1204 | ||

| Age, years | 6017 | 63 (10.1) | 64 (10.1) | 64 (10.3) | 64 (9.8) | 63 (10.1) | 0.11 | 0.41 |

| Sex, % female | 6017 | 63 | 56 | 54 | 48 | 41 | <0.0001 | 0.41 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP), mmHg | 6015 | 122 (21) | 124 (22) | 125 (21) | 126 (21) | 126 (20) | <0.0001 | 0.76 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mmHg | 6015 | 70 (10) | 70 (10) | 70 (9.9) | 71 (10) | 72 (10) | 0.004 | 0.036 |

| Antihypertensive use, % Yes | 5764 | 40 | 38 | 42 | 45 | 42 | 0.035 | 0.045 |

| Hypertension, % yes | 5959 | 42 | 43 | 46 | 48 | 48 | <0.0001 | 0.059 |

| Hypertension categories, % | 5898 | 0.0008 | 0.12 | |||||

| Normotensive, SBP < 140 and DBP < 90 mm Hg | 3258 | 58 | 58 | 55 | 52 | 53 | ||

| Controlled hypertensive, SBP < 140 and DBP < 90 mm Hg | 2151 | 35 | 34 | 37 | 40 | 38 | ||

| Uncontrolled hypertensive, SBP ≥ 140 or DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg |

489 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Diabetes, % yes | 6012 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 22 | <0.0001 | 0.005 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5969 | 5.5 (0.8) | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.6 (0.9) | 5.8 (1.0) | 6.0 (1.4) | <0.0001 | 0.19 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 6013 | 190 (35) | 192 (37) | 192 (35) | 191 (35) | 195 (37) | <0.0001 | 0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 5943 | 112 (32) | 114 (34) | 114 (31) | 113 (31) | 116 (32) | 0.0004 | 0.082 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 6011 | 55 (15) | 54 (16) | 52 (15) | 50 (14) | 48 (14) | <0.0001 | 0.37 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 6013 | 113 (66) | 120 (67) | 130 (79) | 140 (83) | 157 (104) | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

| Statin Use, % yes | 5764 | 22 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 0.110 | 0.32 |

| Aspirin use, % yes | 6005 | 30 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 30 | 0.89 | 0.71 |

| Current alcohol use, % yes | 6002 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 50 | 0.008 | 0.045 |

| Current smoker, % yes | 5972 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 16 | <0.0001 | 0.064 |

| Smoking status, % | 5972 | <0.0001 | 0.081 | |||||

| Never | 2758 | 52 | 49 | 47 | 45 | 38 | ||

| Former | 2542 | 40 | 42 | 42 | 44 | 46 | ||

| Current | 672 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 16 | ||

P-value is a test for trend in linear regression with adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity.

3.2. Plasma P-selectin and subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis

Table 3 summarizes the association of P-selectin and subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis. P-selectin was associated with an average increase in CAC of 136 Agatston units; the association was attenuated but remained significant with adjustment for traditional risk factors (75 Agatston units, P = 0.022). Race/ethnic stratified results illustrate that the magnitude of the average increase in CAC per standard deviation increase in P-selectin independent of traditional risk factors was highest in African Americans followed by non-Hispanic white and Hispanic Americans, with a mean effect of 129, 94, and 29 Agatston units, respectively. In Chinese Americans, however, the association of P-selectin and CAC was null. No significant association was observed for P-selectin levels and IMT in the population. However, in non-Hispanic white Americans, IMT decreased slightly per standard deviation of P-selectin (P = 0.014).

Table 3.

Association of plasma P-selectin residual and coronary artery calcium and incident coronary heart disease.

| All MESA subjects | Non-Hispanic White American | Chinese American | African American | Hispanic American | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (S.E.) | P-value | Beta (S.E.) | P-value | Beta (S.E.) | P-value | Beta (S.E.) | P-value | Beta (S.E.) | P-value | |

| Subclinical disease | ||||||||||

| CAC, Agatston score (exam 2 or 3) | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 136 (32) | <0.0001 | 126 (51) | 0.014 | 54 (81) | 0.50 | 239 (62) | 0.0001 | 83 (68) | 0.22 |

| Model 2 | 75 (33) | 0.022 | 94 (53) | 0.076 | 3.7 (80) | 0.96 | 129 (63) | 0.042 | 29 (70) | 0.68 |

| IMT, mm (exam 2 or 3) | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.41 | −0.011 (0.012) | 0.33 | 0.032 (0.024) | 0.18 | 0.022 (0.016) | 0.17 | 0.008 (0.017) | 0.63 |

| Model 2 | −0.012 (0.008) | 0.14 | −0.030 (0.012) | 0.014 | 0.009 (0.024) | 0.71 | 0.009 (0.017) | 0.61 | −0.012 (0.017) | 0.5 |

| Clinical disease | ||||||||||

| Number of CHD events | 385 | 173 | 32 | 97 | 83 | |||||

| Total person-years | 64,257 | 25,946 | 7,536 | 17,044 | 13,730 | |||||

| Crude CHD rate, per 1,000 person-years | 6.0 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 6.0 | |||||

| Time to coronary heart disease | HR (95% CI) | - | HR (95% CI) | - | HR (95% CI) | - | HR (95% CI) | - | HR (95% CI) | - |

| Model 1 | 1.99 (1.42, 2.77) | <0.0001 | 2.44 (1.48, 4.04) | <0.001 | 1.44 (0.44, 7.74) | 0.55 | 1.81 (0.95, 3.47) | 0.073 | 1.70 (0.84, 3.45) | 0.14 |

| Model 2 | 1.63 (1.15, 2.30) | 0.006 | 1.81 (1.07, 3.07) | 0.027 | 1.32 (0.39, 4.43) | 0.65 | 1.37 (0.69, 2.70) | 0.37 | 1.90 (0.89, 4.06) | 0.096 |

Model 1 = age and sex.

Model 2 = age, sex, BMI, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, current smoking, and diabetes status.

3.3. Plasma P-selectin and CHD

There were 385 CHD events with a median follow-up of 10 years (173 in non-Hispanic white, 97 in African, 83 in Hispanic, and 32 in Chinese Americans). Crude CHD rates per 1000 person-years of follow-up were highest in non-Hispanic white (6.7%) followed by Hispanics, African, and Chinese American, 6.0%, 5.7%, and 4.2%, respectively. The risk of CHD increased 99% per standard deviation increase in P-selectin. The association was attenuated but remained highly significant after adjustment for traditional risk factors (HR: 1.63, P = 0.006). Likewise, in fully adjusted race/ethnic stratified models, a per standard deviation increase in P-selectin was associated with an increase in the risk of CHD of 90% in Hispanic, 81% in non-Hispanic white, 32% in Chinese, and 37% in African Americans. A complete table of parameter estimates for the Framingham risk factors with and without inclusion of P-selectin is presented in Table 4. The cumulative incidence of CHD stratified by quintile of P-selectin is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Association of traditional risk factors and P-selectin residual to coronary heart disease adjusted for race/ethnicity.

| Framingham risk score | Framingham risk score and P-selectin |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age | 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 2.12 (1.68, 2.68) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.62, 2.59) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | <0.001 |

| Using anti-hypertension treatment | 1.41 (1.12, 1.77) | 0.003 | 1.41 (1.12, 1.77) | 0.003 |

| Total cholesterol | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.034 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.077 |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.006 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.017 |

| Current smoker | 1.81 (1.34, 2.45) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.28, 2.34) | <0.001 |

| Diabetic | 1.64 (1.28, 2.11) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.22, 2.02) | <0.001 |

| P-selectin (per standard deviation) | n/a | n/a | 1.64 (1.16, 2.32) | 0.005 |

HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence intervals.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for incident coronary heart disease by quintile of P-selectin. P-value for the log-rank test is 0.005 in fully adjusted model.

4. Discussion

We hypothesized increased P-selectin levels is a risk factor for atherosclerosis. In fact, in this large and diverse population, we have shown that higher P-selectin levels are associated with suboptimal cardiovascular risk factor levels of blood pressure and lipids as well as current smoking and diabetes. However, independent of these risk factors, higher plasma P-selectin levels remains associated with subclinical and clinical CHD with some evidence of race/ethnic heterogeneity. These results provide evidence that plasma P-selectin is an independent marker of increased CHD risk and thus a reasonable candidate for a clinical biomarker.

We observed a positive association of P-selectin and CAC, a surrogate for coronary atherosclerosis, independent of traditional risk factors. Race/ethnic heterogeneity was observed in the association of P-selectin and CAC in that the association of P-selectin was observed in African and non-Hispanic white Americans. The underlying mechanisms for these race/ethnic differences are unknown. However, given the high prevalence of CAC in all four race/ethnic groups, it is highly unlikely that this observed heterogeneity could be explained by power differences related to the ethnic-specific distribution of CAC.

Increased risk of CHD was observed in all groups in the race/ethnic stratified analyses, albeit associations were most compelling for the non-Hispanic whites, confirming results observed in predominantly Caucasian clinical populations [13,25] and in the Women’s Health Study [12]. In contrast to the results for CAC, the power to detect race/ethnic differences with regards to P-selectin and CHD events is reduced due to the limited number of events within each race/ethnic group. Furthermore, the point estimates indicate increased risk of CHD in every race/ethnic group suggesting that P-selectin is indeed a risk factor for CHD common to all groups.

Previous studies report a positive association of P-selectin and IMT in European Americans including the CARDIA Study [16]; to the contrary, we observed a borderline significant inverse relationship in non-Hispanic whites with no evidence of IMT being related to P-selectin in any of the other race/ethnic groups. However one important difference in our study is that the IMT measurements were made in a portion of the common carotid artery selected to be free of plaque. As such, the measurement is more a surrogate of hypertrophy of the medial layer of the common carotid artery and less of a surrogate for atherosclerosis. Whereas in CARDIA, a composite IMT was used that averaged after standardization the maximal common carotid IMT and the internal carotid IMT [16].

Hyperlipidemia is associated with higher plasma P-selectin levels in clinical populations [26-29], and in the CARDIA Study at the year 15 exam in European Americans only [16]. Furthermore, evidence from cell lines shows that hyperlipidemia activates platelets and causes higher P-selectin to atherosclerotic sites [30], and it has been demonstrated that statin therapy reduced P-selectin levels [31-37]. We corroborated these results by observing associations of levels of P-selectin and total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides. While there was no evidence of an association with statin use, we did observe a positive association of P-selectin and LDL that was consistent in all race/ethnicities.

Previous studies reported higher levels of circulating P-selectin in hypertensives compared to normotensives [38-43]. Our observations extend previous findings, with P-selectin levels positively associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and comparing controlled and uncontrolled hypertensives. Shalia et al. reported that mean P-selectin level differences in hypertensives versus normotensives were larger in those less than 40 years of age, albeit in a small sample [43]. MESA recruited those 45 and older thus limiting our ability to characterize differential relationships of P-selectin and hypertension in younger adults. Evidence in the literature suggests a sex-specific positive association of P-selectin levels and smoking status with female smokers having higher P-selectin levels [17,44]. Our results were inconsistent across race-sex strata with no significant sex-interaction observed in any race/ethnicity.

Limitations of the study include the relatively small number of CHD events that may have precluded our ability to determine heterogeneity in the association with CHD. However, the consistency of direction of effect for CHD in every race/ethnic group supports the conclusion that P-selectin in a risk factor for CHD in all groups. As for the associations with traditional CHD risk factors, the sample size is large enough to detect very small differences and these differences, while statistically significant, may not be clinically meaningful. Strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size from four race/ethnic groups, systematic measurement of traditional risk factors, and rigorous ascertainment of subclinical and clinical CHD. The results presented here are important in light of the fact that prior investigations of P-selectin were predominantly limited in sample size and race/ethnic diversity and were commonly drawn from clinical populations.

Additional studies are needed to demonstrate the clinical utility of P-selectin screening for CHD prediction. Currently, P-selectin is not a standard clinical assay. However, it is important to note that clinical assessments of P-selectin are currently being debated to identify those at-risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and to aid in the differential diagnosis of VTE and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [45-47]. Guideline changes in VTE or ACS would increase the clinical availability of p-selectin measurements and make them more common for use in CHD risk algorithms.

5. Conclusions

In a diverse population-based cohort, we demonstrate that P-selectin is an independent risk factor of CHD. Race/ethnic heterogeneity in the association of P-selectin and with subclinical disease suggests possible differences in disease pathophysiology. Further investigations into ethnic-specific expression and regulation of P-selectin may explain the differences observed and investigating repeated measures over time will provide further evidence as to the utility of P-selectin as a clinical biomarker for CHD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

This study was funded by MESA. MESA is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with MESA investigators (Grants and contracts N01 HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, N01-HC-95169 and RR-024156). Funding to support adhesion protein measurements was provided by NHLBI (R01 HL98077, for abdominal aortic CT by grant R01 HL088451, and for IMT measurements by grants R01 HL069003 and R01 HL081352).

Role of the funding source: The funding source had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- [1].Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stenberg PE, McEver RP, Shuman MA, Jacques YV, Bainton DF. A platelet alpha-granule membrane protein (GMP-140) is expressed on the plasma membrane after activation. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:880–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bonfanti R, Furie BC, Furie B, Wagner DD. PADGEM (GMP140) is a component of Weibel-Palade bodies of human endothelial cells. Blood. 1989;73:1109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McEver RP, Beckstead JH, Moore KL, Marshall-Carlson L, Bainton DF. GMP-140, a platelet alpha-granule membrane protein, is also synthesized by vascular endothelial cells and is localized in Weibel-Palade bodies. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:92–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI114175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Andre P, Hartwell D, Hrachovinova I, Saffaripour S, Wagner DD. Pro-coagulant state resulting from high levels of soluble P-selectin in blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13835–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250475997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hamburger SA, McEver RP. GMP-140 mediates adhesion of stimulated platelets to neutrophils. Blood. 1990;75:550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Harrison P, Cramer EM. Platelet alpha-granules. Blood Rev. 1993;7:52–62. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(93)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fijnheer R, Frijns CJ, Korteweg J, Rommes H, Peters JH, Sixma JJ, Nieuwenhuis HK. The origin of P-selectin as a circulating plasma protein. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:1081–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kisucka J, Chauhan AK, Zhao BQ, Patten IS, Yesilaltay A, Krieger M, Wagner DD. Elevated levels of soluble P-selectin in mice alter blood-brain barrier function, exacerbate stroke, and promote atherosclerosis. Blood. 2009;113:6015–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].An G, Wang H, Tang R, Yago T, McDaniel JM, McGee S, Huo Y, Xia L. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is highly expressed on Ly-6Chi monocytes and a major determinant for Ly-6Chi monocyte recruitment to sites of atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2008;117:3227–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gitlin JM, Homeister JW, Bulgrien J, Counselman J, Curtiss LK, Lowe JB, Boisvert WA. Disruption of tissue-specific fucosyltransferase VII, an enzyme necessary for selectin ligand synthesis, suppresses atherosclerosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:343–50. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N. Soluble P-selectin and the risk of future cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2001;103:491–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Varughese GI, Patel JV, Tomson J, Blann AD, Hughes EA, Lip GY. Prognostic value of plasma soluble P-selectin and von Willebrand factor as indices of platelet activation and endothelial damage/dysfunction in high-risk patients with hypertension: a sub-study of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial. J Intern Med. 2007;261:384–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Snoep JD, Roest M, Barendrecht AD, De Groot PG, Rosendaal FR, Van Der Bom JG. High platelet reactivity is associated with myocardial infarction in premenopausal women: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Homeost. 2010;8:906–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee DS, Larson MG, Lunetta KL, Dupuis J, Rong J, Keaney JF, Lipinska I, Baldwin CT, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Clinical and genetic correlates of soluble P-selectin in the community. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:20–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reiner AP, Carlson CS, Thyagarajan B, Rieder MJ, Polak JF, Siscovick DS, Nickerson DA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Gross MD. Soluble P-selectin, SELP polymorphisms, and atherosclerotic risk in European-American and African-African young adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1549–55. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.169532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Demerath E, Towne B, Blangero J, Siervogel RM. The relationship of soluble ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin and E-selectin to cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy men and women. Ann Hum Biol. 2001;28:664–78. doi: 10.1080/03014460110048530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O'Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD, Detrano RC. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Polak JF, Pencina MJ, O'Leary DH, D'Agostino RB. Common carotid artery intima-media thickness progression as a predictor of stroke in multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2011;42:3017–21. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Johnson C, Polak JF, Post W, Lima JA, Crouse JR, Herrington DM. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;120:502–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years' experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–33. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fornage M, Boerwinkle E, Doris PA, Jacobs D, Liu K, Wong ND. Polymorphism of the soluble epoxide hydrolase is associated with coronary artery calcification in African-American subjects: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2004;109:335–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109487.46725.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tobin J. Estimation for relationships with limited dependent variables. Econometrica. 1958;26:24–36. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Blann AD, Faragher EB, McCollum CN. Increased soluble P-selectin following myocardial infarction: a new marker for the progression of atherosclerosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kvasnicka T, Kvasnicka J, Ceska R, Vrablik M. Increase of inflammatory state in overweight adults with combined hyperlipidemia. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;13:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0939-4753(03)80015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Blann AD, Goode GK, Miller JP, McCollum CN. Soluble P-selectin in hyperlipidaemia with and without symptomatic vascular disease: relationship with von Willebrand factor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:200–4. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Davi G, Romano M, Mezzetti A, Procopio A, Iacobelli S, Antidormi T, Bucciarelli T, Alessandrini P, Cuccurullo F, Bittolo Bon G. Increased levels of soluble P-selectin in hypercholesterolemic patients. Circulation. 1998;97:953–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cipollone F, Mezzetti A, Porreca E, Di Febbo C, Nutini M, Fazia M, Falco A, Cuccurullo F, Davi G. Association between enhanced soluble CD40L and prothrombotic state in hypercholesterolemia: effects of statin therapy. Circulation. 2002;106:399–402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025419.95769.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Theilmeier G, Michiels C, Spaepen E, Vreys I, Collen D, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. Endothelial von Willebrand factor recruits platelets to atherosclerosis-prone sites in response to hypercholesterolemia. Blood. 2002;99:4486–93. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Romano M, Mezzetti A, Marulli C, Ciabattoni G, Febo F, Di Ienno S, Roccaforte S, Vigneri S, Nubile G, Milani M, Davi G. Fluvastatin reduces soluble P-selectin and ICAM-1 levels in hypercholesterolemic patients: role of nitric oxide. J Investig Med. 2000;48:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bickel C, Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, Espinola-Klein C, Rippin G, Hafner G, Lotz J, Prellwitz W, Meyer J. Influence of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on markers of coagulation, systemic inflammation and soluble cell adhesion. Int J Cardiol. 2002;82:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(01)00576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Berkan O, Katrancioglu N, Ozker E, Ozerdem G, Bakici Z, Yilmaz MB. Reduced P-selectin in hearts pretreated with fluvastatin: a novel benefit for patients undergoing open heart surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:91–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kirk G, McLaren M, Muir AH, Stonebridge PA, Belch JJ. Decrease in P-selectin levels in patients with hypercholesterolaemia and peripheral arterial occlusive disease after lipid-lowering treatment. Vasc Med. 1999;4:23–6. doi: 10.1177/1358836X9900400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee WJ, Lee WL, Tang YJ, Liang KW, Chien YH, Tsou SS, Sheu WH. Early improvements in insulin sensitivity and inflammatory markers are induced by pravastatin in nondiabetic subjects with hypercholesterolemia. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;390:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marschang P, Friedrich GJ, Ditlbacher H, Stoeger A, Nedden DZ, Kirchmair R, Dienstl A, Pachinger O, Patsch JR. Reduction of soluble P-selectin by statins is inversely correlated with the progression of coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Oka H, Ikeda S, Koga S, Miyahara Y, Kohno S. Atorvastatin induces associated reductions in platelet P-selectin, oxidized low-density lipoprotein, and interleukin-6 in patients with coronary artery diseases. Heart Vessels. 2008;23:249–56. doi: 10.1007/s00380-008-1038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nadar SK, Blann AD, Lip GY. Plasma and platelet-derived vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-1 in hypertension: effects of antihypertensive therapy. J Intern Med. 2004;256:331–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Spencer CG, Gurney D, Blann AD, Beevers DG, Lip GY. Von Willebrand factor, soluble P-selectin, and target organ damage in hypertension: a substudy of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) Hypertension. 2002;40:61–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000022061.12297.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lip GY, Blann AD, Zarifis J, Beevers M, Lip PL, Beevers DG. Soluble adhesion molecule P-selectin and endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension: implications for atherogenesis? A preliminary report. J Hypertens. 1995;13:1674–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Preston RA, Coffey JO, Materson BJ, Ledford M, Alonso AB. Elevated platelet P-selectin expression and platelet activation in high risk patients with uncontrolled severe hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nomura S, Inami N, Shouzu A, Urase F, Maeda Y. Correlation and association between plasma platelet-, monocyte- and endothelial cell-derived microparticles in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Platelets. 2009;20:406–14. doi: 10.1080/09537100903114545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shalia KK, Mashru MR, Vasvani JB, Mokal RA, Mithbawkar SM, Thakur PK. Circulating levels of cell adhesion molecules in hypertension. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2009;24:388–97. doi: 10.1007/s12291-009-0070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Butkiewicz AM, Kemona-Chetnik I, Dymicka-Piekarska V, Matowicka-Karna J, Kemona H, Radziwon P. Does smoking affect thrombocytopoiesis and platelet activation in women and men? Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ay C, Dunkler D, Marosi C, Chiriac AL, Vormittag R, Simanek R, Quehenberger P, Zielinski C, Pabinger I. Prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Blood. 2010;116:5377–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blann AD. Soluble P-selectin: the next step. Thromb Res. 2014;133:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Antonopoulos CN, Sfyroeras GS, Kakisis JD, Moulakakis KG, Liapis CD. The role of soluble P selectin in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2014;133:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.