Abstract

Importance

Several large-scale Alzheimer's disease (AD) secondary prevention trials have begun to target individuals at the preclinical stage. The success of these trials depends on validated outcome measures that are sensitive to early clinical progression in individuals who are initially asymptomatic.

Objective

To investigate the utility of the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) to track early changes in cognitive function in older individuals without clinical impairment at baseline.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Longitudinal study over the course of 48 months at participating Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) sites. The study included 468 healthy older individuals (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale [CDR] Global = 0, above cut-off on modified Mini-Mental State Exam and Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test) (mean age= 79.4 years ±3.6). All subjects and their study partners completed the Self and Partner CFI annually. Subjects also underwent concurrent annual neuropsychological assessment and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping.

Main outcomes and measures

Comparison of CFI scores between clinical progressors (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale [CDR] ≥ 0.5) and non-progressors (CDR remained = 0), as well as between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers were performed. Correlations of change between the CFI and neuropsychological performance were assessed longitudinally.

Results

At 48 months, group differences between clinical progressors and non-progressors were significant for CFI Self, CFI Partner, and CFI Self+Partner total scores. At month 48, APOE ε4 carriers showed greater progression than non-carriers on CFI Partner and CFI Self+Partner scores. Both CFI Self and CFI Partner scores were associated with longitudinal cognitive decline, although findings suggest self report may be more accurate early in the process, whereas accuracy of partner report improves when there is progression to cognitive impairment.

Conclusions and Relevance

Demonstrating long-term clinical benefit will be critical for the success of recently launched secondary prevention trials. The CFI appears to be a brief, yet informative potential outcome measure that provides insight into functional abilities at the earliest stages of disease.

INTRODUCTION

Recently published guidelines have outlined a “preclinical phase” of AD in which individuals are still clinically normal, but may have subtle evidence of early cognitive change in the context of amyloidosis and neuronal injury1. This provides the opportunity to intervene at earlier stages of disease than was previously possible2. Recent guidance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that a primary cognitive outcome measure may suffice for provisional approval of a preclinical treatment, but eventually would need to be supported by evidence of long-term functional benefit3. Currently, sensitive cognitive measures are available for secondary prevention trials4,5, but a companion functional measure has yet to be fully realized6.

Increasingly, subjective report of cognitive functioning in everyday life is thought to be a sensitive indicator of decline, even at the preclinical stages of AD7–13. Accordingly, over the last decade, the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) has developed the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) intended to detect early changes in cognitive and functional abilities in individuals without clinical impairment14. The CFI includes 14 questions that are asked of the participant and a study partner separately that efficiently probe the full realm of subjective cognitive concerns found in older adults15. Unlike functional outcomes typically used in clinical trials at the stage of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or dementia, the CFI does not require an in-person interview or clinician judgment and measures both participant and study partner report, the combination of which has been shown to be sensitive at the earliest stages of disease16.

In the current study, the goal was to determine if the CFI is a sensitive measure in tracking longitudinal change in cognitive function in older individuals without cognitive impairment at baseline. Over the course of four years, we assessed the CFI's (self and partner) relationship with clinical progression (on Clinical Dementia Rating Scale), apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 carrier status, and performance on a cognitive composite. Ultimately, we sought to establish the CFI as a useful functional measure appropriate for prevention trials.

METHODS

A total of 468 older individuals (60% female) with an average age of 79.4 (±3.6) years participated in the study. Participants met inclusion criteria if they were in good physical and mental health, had no significant medical illnesses that would interfere with participation (e.g., active malignancy, stroke), and no exclusionary medications (e.g., antipsychotic agents). Participants were required to have a qualified study partner who was willing to provide information about their daily function and who had contact with the participant at least 2 times per week. The participants were enrolled at multiple ADCS sites. The local Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study protocol and informed consent form before the initiation of participant recruitment. All participants provided informed consent after the procedures of the study had been fully explained. In the current sample, participants had a global Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR-G)17 score = 0 at baseline, a modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MSE)18 of at least 88 for participants with greater than 8 years of education and at least 80 for participants with less education (taken from the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS)), and a score greater than 44 on the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test total score, which includes both free and cued recall (FCSRT)19. The CFI was not used to determine participant eligibility in this study. Individuals were followed annually for 48 months following the baseline visit.

Participants and study partners were mailed the CFI 4 weeks prior to each annual assessment and were asked to return the questionnaire by mail. Participants and study partners were asked to complete the CFI independently. The study partner was not allowed to consult the subject, but could consult anyone else. The CFI contains 14 questions (see Tables 1&2); one version for the participant and one version for the study partner with the same questions. Questions were originally derived from common probes across clinical assessments of aging and dementia14 and include items regarding memory decline (e.g., compared to a year ago, memory has declined), appraisal of cognitive difficulties (e.g., misplacing belongings more often), and functional abilities (e.g., need more help remembering appointments). Responses were coded as Yes = 1, No= 0, and Maybe = 0.5, and were summed together to create a total score.

Table 1.

Cognitive Function Instrument: Self report

| Answer all questions with reference to one year ago. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Compared to one year ago, do you feel that your memory has declined substantially? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

|

| ||||

| 2. | Do others tell you that you tend to repeat questions over and over? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 3. | Have you been misplacing things more often? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 4. | Do you find that lately you are relying more on written reminders (e.g., shopping lists, calendars)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 5. | Do you need more help from others to remember appointments, family occasions or holidays? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 6. | Do you have more trouble recalling names, finding the right word, or completing sentences? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 7. | Do you have more trouble driving (e.g., do you drive more slowly, have more trouble at night, tend to get lost, have accidents)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 8. | Compared to one year ago, do you have more difficulty managing money (e.g., paying bills, calculating change, completing tax forms)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 9. | Are you less involved in social activities? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 10. | Has your work performance (paid or volunteer) declined significantly compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 11. | Do you have more trouble following the news, or the plots of books, movies or TV shows, compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 12. | Are there any activities (e.g., hobbies, such as card games, crafts) that are substantially more difficult for you now compared to one yea ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 13. | Are you more likely to become disoriented, or get lost, for example when traveling to another city? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 14. | Do you have more difficulty using household appliances (such as the washing machine, VCR or computer)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

Table 2.

Cognitive Function Instrument: Study partner report

| Answer all questions with reference to one year ago. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Do you feel the subject has had a significant decline in memory compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

|

| ||||

| 2. | Does the subject tend to ask the same question over and over? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 3. | Has the subject been misplacing things more often? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 4. | Does it seem to you that lately the subject is relying more on written reminders (e.g., shopping lists, calendars)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 5. | Does the subject need more help from others to remember appointments, family occasions or holidays? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 6. | Does the subject have more trouble recalling names, finding the right word, or completing sentences? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 7. | Is the subject having more trouble driving (e.g., do you drive more slowly, have more trouble at night, tend to get lost, have accidents)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 8. | Compared to one year ago, is the subject having more difficulty managing money (e.g., paying bills, calculating change, completing tax forms)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 9. | Is the subject less interested in social activities? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 10. | Do you believe, based on your own observations or comments from the subject's co-workers, that the subject's work performance (paid or volunteer) has declined significantly, compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 11. | Does the subject have more trouble following the news, or the plots of books, movies or TV shows, compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 12. | Are there any activities (e.g., hobbies, such as card games, crafts) that are substantially more difficult for the subject now compared to one year ago? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 13. | Is the subject more likely to become disoriented, or get lost, for example when traveling to another city? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

| 14. | Does the subject have more difficulty using household appliances (such as the washing machine, VCR or computer)? | □ Yes | □ No | □ Maybe |

Objective cognitive performance was assessed annually with a cognitive battery called the modified Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (mADCS-PACC), a modified version of the ADCS-PACC4, described in a separate study, which has demonstrated sensitivity in detecting cognitive decline at the preclinical stage of AD. Briefly, the mADCS-PACC consisted of 1) total recall from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) (0 to 48 words)19, 2) NYU Paragraph recall20, 3) Digit-Symbol Substitution Test score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (0 to 93 symbols)21 and 4) Modified Mini Mental State Exam (3MSE)18 score. NYU Paragraph recall and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test were not given at baseline, but at all subsequent visits. At each annual follow-up visit, participants were screened for the development of MCI or dementia based the same cut-offs used as inclusion criteria (3MSE and FCSRT). If an individual fell below either 2 cut-offs on the cognitive evaluation, then the site clinician initiated a clinical consensus to determine if the participant met Petersen criteria22 for MCI or DSM IV for dementia and if so, whether or not the probable etiology was AD.

Among those with at least one follow-up CFI observation, we summarized means, standard deviations, counts, and percentages of characteristics at baseline by groups of interest. One group of interest included individuals who progressed from 0 to 0.5 or higher on CDR-G at any time point after baseline. None of the subjects who progressed on CDR regressed on CDR at a later time point. We also compared individuals who had at least one APOE ε4 allele (APOEε4+) against non-carriers (APOEε4−). Groups were compared using Pearson's Chi-square test for categorical data; and the two-sample t-test for continuous data. We assessed internal consistency, using Cronbach's alpha, on the items of the CFI in our sample for both self and study partner versions. In individuals who were CDR-G stable and APOEε4−, we estimated intraclass correlation coefficients to assess test-retest reliability from baseline to 12 months later23. To assess group differences in longitudinal change, we applied a Mixed Model of Repeated Measures 24 with baseline CFI, baseline Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 25, age, education, and race considered as covariates. Time was treated as a categorical variable. We assumed a compound symmetric correlation structure and heterogeneous variance over time. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Secondary analyses compared CFI items that represented appraisal of cognitive abilities in everyday life (e.g., repeating questions) to those that were more related to functional abilities (e.g., change in ability to use appliances) in predicting outcomes. We also regressed CDR-G progression status on CFI and PACC baseline scores to assess the predictive value of each predictor separately and together. The predictive value of these logistic regression models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)26. This analysis was repeated with CFI and PACC change scores, estimated by the slope estimates from subject-level ordinary least squares regression.

To assess the correlation between the CFI versions (Self, Partner, Self+Partner) and the mADCS-PACC, we estimated cross-sectional Pearson's correlation coefficients at each visit. We used the nonparametric bootstrap, resampling subjects with replacement 10,000 times, to obtain confidence intervals for the pairwise differences between these correlations at each time point (Self vs Partner, Self vs Self+Partner, and Partner vs Self+Partner). We also applied a multivariate outcome linear mixed-effect model approach to estimate the correlation of change in CFI and mADCS-PACC27. Confidence intervals were again derived by nonparametric bootstrap in which we resampled subjects, with replacement, 1,000 times and refit the mixed-effect model for each resample.

RESULTS

Tables 3 and 4 provide the baseline characteristics by the groups of interest. The CDR-G Stable group demonstrated better performance than the CDR-G Progressor group on the FCSRT Free Recall, 3MSE, and all three versions of CFI (Self, Partner, and Self+Partner). The APOEε4-group was older and had higher GDS scores at baseline than the APOEε4+ group. Individuals who dropped from the study were more likely to be older, of minority status, and with lower education. Performance on the 3MSE and PACC were lower at the time of the last visit, but no differences were found on the CDR.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by CDR-G Progression group.

| N | CDR-G Stable (N=441) | CDR-G Progressors (N=27) | Combined (N=468) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOEε4+ | 286 | 60 (22%) | 4 (24%) | 64 (22%) | 0.906 |

| Female | 468 | 260 (59%) | 19 (70%) | 279 (60%) | 0.241 |

| Age (years) | 468 | 79.4 (3.6) | 80.5 (3.8) | 79.4 (3.6) | 0.131 |

| Education (years) | 468 | 15.1 (2.9) | 14.1 (3.5) | 15.1 (3.0) | 0.152 |

| Ethnicity | 0.125 | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 8 (2%) | 2 (7%) | 10 (2%) | ||

| Black, not of Hispanic Origin | 54 (12%) | 5 (19%) | 59 (13%) | ||

| Hispanic | 28 (6%) | 4 (15%) | 32 (7%) | ||

| White, not Hispanic Origin | 348 (79%) | 16 (59%) | 364 (78%) | ||

| Other or unknown | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| FCSRT Free | 467 | 29.1 (5.5) | 25.4 (6.0) | 28.8 (5.6) | 0.004 |

| FCSRT Total | 467 | 47.9 (0.4) | 47.6 (0.8) | 47.8 (0.5) | 0.074 |

| CDR-SB : 0.5 | 468 | 77 (17%) | 8 (30%) | 85 (18%) | 0.111 |

| 3MSE | 468 | 95.9 (3.3) | 92.0 (4.1) | 95.7 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| GDS | 468 | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.8) | 0.066 |

| CFI Self | 468 | 1.9 (1.9) | 3.4 (2.4) | 2.0 (1.9) | 0.003 |

| CFI Partner | 468 | 0.9 (1.4) | 2.1 (2.5) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.027 |

| CFI Self+Partner | 468 | 2.8 (2.7) | 5.5 (4.0) | 3.0 (2.8) | 0.002 |

Data include all subjects with at least one follow-up CFI observation. For categorical data, we provide counts, percentages, and Pearson's Chi-square Test. For continuous data, we provide means, standard deviations, and two-sample t-test. P-values less than 0.05 are in bold.

APOEε4+ = At least one APOE;4 allele; FCSRT = Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes; 3MSE = Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; CFI = Cognitive Function Instrument

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics by APOEε4 group.

| N | APOEε4− (N=222) | APOEε4+ (N=64) | Combined (N=286) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR-G | |||||

| Progressors | 286 | 13 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 17 (6%) | 0.906 |

| Female | 286 | 127 (57%) | 39 (61%) | 166 (58%) | 0.594 |

| Age (years) | 286 | 79.6 (3.6) | 78.3 (3.0) | 79.3 (3.5) | 0.004 |

| Education (years) | 286 | 15.1 (3.2) | 15.2 (2.9) | 15.1 (3.1) | 0.715 |

| Ethnicity | 286 | 0.324 | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (2%) | ||

| Black, not of Hispanic Origin | 21 (9%) | 12 (19%) | 33 (12%) | ||

| Hispanic | 17 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 22 (8%) | ||

| White, not Hispanic Origin | 177 (80%) | 46 (72%) | 223 (78%) | ||

| Other or unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| FCSRT Free | 285 | 28.7 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.1) | 29.0 (5.8) | 0.118 |

| FCSRT Total | 285 | 47.8 (0.5) | 47.9 (0.4) | 47.9 (0.5) | 0.103 |

| CDR-SB : 0.5 | 286 | 47 (21%) | 11 (17%) | 58 (20%) | 0.485 |

| 3MSE | 286 | 95.7 (3.8) | 96.1 (3.0) | 95.8 (3.6) | 0.411 |

| GDS | 286 | 1.6 (2.1) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.4 (2.0) | 0.003 |

| CFI Self | 286 | 2.0 (2.1) | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.1 (2.0) | 0.402 |

| CFI Partner | 286 | 1.0 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.707 |

| CFI Self+Partner | 286 | 3.0 (3.0) | 3.3 (2.6) | 3.1 (3.0) | 0.450 |

Data include all subjects with known APOEε4 status and at least one follow-up CFI observation. For categorical data, we provide counts, percentages, and Pearson's Chi-square Test. For continuous data, we provide means, standard deviations, and two-sample t-test. P-values less than 0.05 are in bold.

APOEε4− = No APOEε4 alleles; APOEε4+ = At least one APOEε4 allele; FCSRT = Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes; 3MSE = Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; CFI = Cognitive Function Instrument

Cronbach's alpha of CFI Self items at baseline was 0.78 and CFI Partner was 0.85. In individuals who were CDR-G Stable and APOE ε4 non-carriers, intraclass correlations for CFI Self was 0.73 and for CFI Partner was 0.54 (5% of the study partners changed from baseline to month 12).

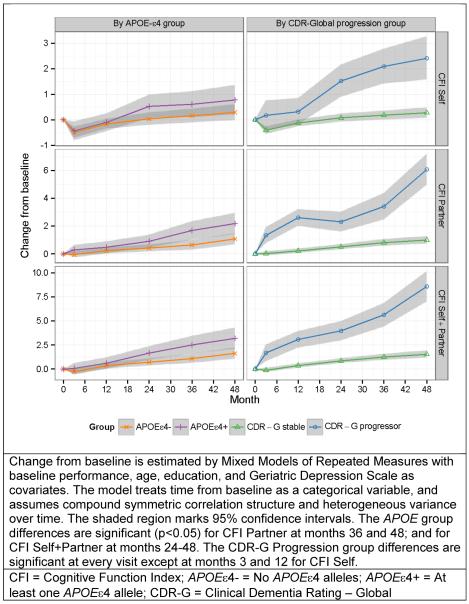

Figure 1 demonstrates the estimated group differences in CFI change from baseline by APOE and CDR-G Progressor groups. When compared to the APOEε4− subjects, APOEε4+ subjects were found to have worse functioning on the CFI over time: The APOE group differences were significant (p<0.05) for CFI Partner at months 36 (Δ=1.04, SE=0.38, p=0.007) and 48 (Δ=1.10, SE=0.44, p=0.012); and for CFI Self+Partner at months 24 (Δ=0.94, SE=0.40, p=0.020), 36 (Δ=1.42, SE=0.53, p=0.007), and 48 (Δ=1.56, SE=0.63, p=0.014). When compared to the CDR-G stable subjects, CDR-G progressors were found to have worse functioning on the CFI over time: The CDR-G Progression group differences were significant for CFI Self, Partner, Self+Partner at every visit except at months 3 and 12 for CFI Self. At month 48 the group differences were Δ=2.13 (SE=0.45, p<0.001) for CFI Self, Δ=5.08 (SE=0.59, p<0.001) for CFI Partner, and Δ=7.04 (SE=0.83, p<0.001) for CFI Self+Partner. A composite of items grouped by functional abilities (e.g., remembering appointments) versus a composite of metacognitive items (e.g., repeating conversations), performed similarly at separating CDR and APOE groups longitudinally.

Figure 1. Comparison of CFI Self, Partner, and Self+Partner change from baseline by APOE ε4 carrier status and by global Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) progression status.

Change from baseline is estimated by Mixed Models of Repeated Measures with baseline performance, age, education, and Geriatric Depression Scale as covariates. The model treats time from baseline as a categorical variable, and assumes compound symmetric correlation structure and heterogeneous variance over time. The shaded region marks 95% confidence intervals. The APOE group differences are significant (p<0.05) for CFI Partner at months 36 and 48; and for CFI Self+Partner at months 24–48. The CDR-Global Progression group differences are significant at every visit except at months 3 and 12 for CFI Self.

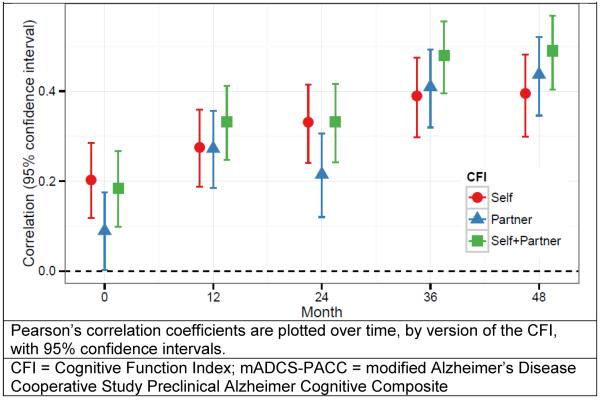

Figure 2 demonstrates the cross-sectional correlation between CFI and mADCS-PACC. Worse functioning on the CFI was associated with worse cognition on the mADCS-PACC: The correlation between CFI Self and mADCS-PACC increased from ρ=0.20 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.29) at baseline to ρ=0.39 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.48) at month 48, while the correlation between CFI Partner and mADCS-PACC increased from ρ=0.09 (95% CI 0.002 to 0.18) at baseline to ρ=0.44 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.52) at month 48. The correlation between CFI Self + Partner and mADCS-PACC increased from ρ=0.18 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.27) at baseline to ρ=0.49 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.57) at month 48. The bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the pairwise differences between correlations with the mADCS-PACC excluded 0 for all differences except between CFI Self and CFI Self+Partner at baseline and month 24; and CFI Self and CFI Partner at months 12, 36, and 48. The multivariate mixed-effect model analysis found the correlation of change between CFI Self and mADCS-PACC was ρ=0.32 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.46), between CFI Partner and mADCS-PACC was ρ=0.56 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.68), and between CFI Self + Partner and mADCS-PACC was ρ=0.58 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.70). The correlation of change between mADCS-PACC and CFI-Self + Partner was significantly stronger than with CFI-Self (0.27, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.46). The correlation of change between mADCS-PACC and CFI- Self + Partner was stronger than with CFI-Partner (0.02, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.13), and stronger with CFI-Partner than with CFI-Self (0.25, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.53), but these differences were not significant at the 0.05 level.

Figure 2. Correlation between CFI (Self, Partner, and Self+Partner) and mADCS-PACC over time.

Pearson's correlation coefficients are plotted over time, by version of the CFI, with 95% confidence intervals. Signs for the correlations are inverted.

The logistic regression models of CDR-G progression found that both baseline mADCS-PACC and CFI were independently predictive. Each point increase on the PACC was associated with a decreased risk of progression (OR=0.965, 95% CI 0.95 to 0.98, p<0.001), and each point increase on the CFI was associated with increased risk of progression (OR = 1.013, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.02, p<0.001). The model that included both measures had the best predictive value (AIC = −100.2), followed by the models with mADCS-PACC alone (AIC = −89.3) and CFI alone (AIC = −78.1).

DISCUSSION

Overall, we found that both self and partner report of change in cognitive function on the CFI was associated with traditional measures of clinical progression over the course of four years. When comparing individuals who demonstrated clinical progression (CDR-G>0) to those who remained stable (CDR-G=0), there was a significant separation between groups, such that CDR-G progressors exhibited higher CFI scores, as well as a greater increase in CFI scores over time than did CDR-G stable. These findings held for both partner and self report. The combination of self+partner CFI demonstrated a slight advantage over individual report, suggesting that both perspectives on decline might be valuable over a 4 year observational period.

The CFI remained a predictor of CDR progression when objective cognitive performance was also added as a predictor, suggesting that it independently contributes to longitudinal outcomes, but that the combination of both measures may be particularly predictive. Findings are in support of a previous work that finds both subjective and objective measures improve predictive ability in individuals without clinical impairment28 and with MCI29.

When comparing APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers, there was a significant separation between carrier groups by month 36 for partner CFI, whereas self CFI was not different between carrier groups at any time point. However, the combination of self+partner CFI differentiated between groups at month 24 and demonstrated the greatest separation between groups, although not statistically different from self and study partner alone.

Additional analyses did not reveal significant differences between CFI items that represented appraisal of cognitive abilities in everyday life (e.g., repeating questions) compared to report of functional abilities (e.g., change in ability to use appliances). Questions regarding cognitive difficulties or functional abilities performed equally as well at differentiating between progressors and non-progressors, or APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers, suggesting that both are valuable in assessing subjective report of everyday functioning.

When assessing the correlation between longitudinal change in CFI compared to longitudinal change on an objective cognitive composite, we found that both increased partner CFI and self CFI were associated with greater objective cognitive decline. When we examined the correlation between CFI and objective cognitive performance on the mADCS-PACC at each time point, we saw, at baseline and month 24, that self CFI demonstrated significantly stronger correlations with cognitive performance than partner CFI. Both self and partner report were significantly inferior to the combined report at months 12, 36 and 48, suggesting that the combination is particularly powerful in detecting subtle cognitive decline. Self-report was significantly superior to partner-report at baseline and month 24; while partner report was numerically superior (but did not reach statistical significance) at months 36 and 48. One interpretation is that while self-report is more reliably correlated with cognition earlier in the process of decline, partner-report might become more useful later with development of anosognosia16,30.

Reliability analyses revealed that internal consistency of items was at acceptable levels for both self and study partner report. Intraclass correlations revealed that in individuals who were CDR-G stable and APOE ε4 non-carriers, self-report was more reliable after 12 months than for the study partner despite only a 5% turn over rate in study partners. This finding may be due to the fact that study partners are not in a caregiving role as participants were all independent in their everyday activities at baseline, and suggests that the combination of self and partner report may be more reliable in tracking change in individuals who begin at an asymptomatic stage.

Results suggest that the CFI can serve as a sensitive functional outcome measure in secondary prevention trials. Brief and easily administered on an annual basis in the current study, it contains questions that cover the full realm of early functional change. Importantly, the CFI can be self-administered at home, with forms mailed 14, and with the potential to administer over the phone or transmit electronically; thus the CFI could be used in large, lengthy prevention trials with minimal in-person contact between participants and investigators. Historically, clinical trials involving patients at the stage of MCI or AD dementia have included more detailed functional measures such as the CDR 17, which requires a clinician's judgment, or the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) 31, which is weighted heavily toward a study partner's report. In addition to the CFI, the ADCS has developed a more extensive functional measure, called the Activities of Daily Living- Prevention Instrument (ADL-PI) 32. This questionnaire has also demonstrated sensitivity in detecting early functional change, however it takes longer to administer than the CFI and does not include questions about self-appraisal of memory function, a feature that may important to capture early progression along the preclinical stages of AD.

Several potential limitations of this study deserve mention. Biomarker data was not available to confirm the etiology of cognitive decline in our sample. While items of the CFI were originally selected to target changes commonly experienced in functional impairment due to AD, it is possible that this instrument is sensitive to changes associated with other etiologies. Follow-up studies that explore relationships with putative AD biomarkers will be informative.

Additionally, there is some overlap in the types of questions asked in the CFI and the CDR, which may lead to enhancement of findings when looking at clinical progression outcomes. However, differences on CFI were found at baseline when all participants had a CDR = 0, suggesting that the CFI could be more sensitive than the CDR in a sample without clinical impairment. Furthermore, we found that the CFI tracked with objective cognitive decline providing support for its utility.

As the Alzheimer's field moves toward prevention at the preclinical stages of disease, many new hurdles emerge. In addition to identifying the appropriate target for disease modification, finding the right tools to detect the earliest evidence of clinical progression is challenging. Demonstrating long-term clinical benefit will be critical, since maintaining independence in everyday functioning is what matters most to patients and their families. Subjective assessment of an individual's level of functioning over time, using the CFI, may prove to be a sensitive and efficient outcome for secondary prevention trials in preclinical AD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R. Amariglio had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

R. Amariglio: design of the study; interpretation of the data; preparation of the manuscript

M. Donohue: design of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation of the manuscript; review and approval of the manuscript

G. Marshall: design of the study; interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

D. Rentz: design of the study; interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

D. Salmon: design of the study; collection and interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

S. Ferris: design of the study; collection and interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

S. Karantzoulis: interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

P. Aisen: design of the study; collection and interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

R. Sperling: design of the study; interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript

The authors wish to acknowledge the staff of the ADCS, the site personnel from the ADCS – Prevention Instrument Trial, and all of the participants who dedicated their time to this study. This work was supported by grants from the Alzheimer's Association NIRG-12-243012 (Amariglio) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH): U19 AG10483 (Aisen), K24 AG035007 (Sperling), P01 AG036694 (Sperling), K23AG044431 (Amariglio).

This work was supported by grants from the Alzheimer's Association NIRG-12-243012 (Amariglio) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH): U19 AG10483 (Aisen), K24 AG035007 (Sperling), P01 AG036694 (Sperling), K23AG044431 (Amariglio).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr., Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111–133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidance for industry: Alzheimer's disease: developing drugs for the treatment of early stage disease (Draft Guidance) United States Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. The Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rentz DM, Parra Rodriguez MA, Amariglio R, Stern Y, Sperling R, Ferris S. Promising developments in neuropsychological approaches for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer's disease: a selective review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(6):58. doi: 10.1186/alzrt222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozauer N, Katz R. Regulatory innovation and drug development for early-stage Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1169–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hohman TJ, Beason-Held LL, Lamar M, Resnick SM. Subjective cognitive complaints and longitudinal changes in memory and brain function. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(1):125–130. doi: 10.1037/a0020859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2045–2051. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, Leng L, Zhu W. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010 Jan;6(1):11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessen F, Feyen L, Freymann K, et al. Volume reduction of the entorhinal cortex in subjective memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(12):1751–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, et al. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67(5):834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(12):2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel, et al. Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative Working, G A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh SP, Raman R, Jones KB, Aisen PS. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study G. ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI) Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4 Suppl 3):S170–178. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213879.55547.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snitz BE, Yu L, Crane PK, Chang CC, Hughes TF, Ganguli M. Subjective Cognitive Complaints of Older Adults at the Population Level: An Item Response Theory Analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(4):344–351. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gifford KA, Liu D, Lu Z, et al. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng E, Chui H. The modified mini mental state (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grober E, Merling A, Heimlich T, Lipton RB. Free and cued selective reminding and selective reminding in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19(5):643–654. doi: 10.1080/01688639708403750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kluger A, Ferris SH, Golomb J, Mittelman MS, Reisberg B. Neuropsychological Prediction of Decline to Dementia in Nondemented Elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:168–179. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of internal medicine. 2004 Sep;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological bulletin. 1979 Mar;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallinckrodt CH, Clark WS, David SR. Accounting for dropout bias using mixed-effects models. J Biopharm Stat. 2001;11(1–2):9–21. doi: 10.1081/BIP-100104194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale. Psychiatry Res. 1983;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions of Automatic COntrol. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckett LA, Tancredi DJ, Wilson RS. Multivariate longitudinal models for complex change processes. Stat Med. 2004;23(2):231–239. doi: 10.1002/sim.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohman TJ, Beason-Held LL, Lamar M, Resnick SM. Subjective cognitive complaints and longitudinal changes in memory and brain function. Neuropsychology. 2011 Jan;25(1):125–130. doi: 10.1037/a0020859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfsgruber S, Wagner M, Schmidtke K, et al. Memory concerns, memory performance and risk of dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. PloS one. 2014;9(7):e100812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caselli RJ, Chen K, Locke DE, et al. Subjective cognitive decline: Self and informant comparisons. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S. Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer's disease: the disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(5):471–481. doi: 10.5014/ajot.53.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galasko D, Bennett DA, Sano M, et al. ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: assessment of instrumental activities of daily living for community-dwelling elderly individuals in dementia prevention clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4 Suppl 3):S152–169. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213873.25053.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]