Abstract

Peer and parental influences are critical socializing forces shaping adolescent development, including the co-evolving processes of friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking. This study examines aspects of adolescent friendship networks and dimensions of parental influences shaping friendship tie choice and smoking, including parental support, parental monitoring, and the parental home smoking environment using a Stochastic Actor-Based model. With data from three waves of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health of youth in grades 7 through 12, including the In-School Survey, the first wave of the In-Home survey occurring 6 months later, and the second wave of the In-Home survey, occurring one year later, this study utilizes two samples based on the social network data collected in the longitudinal saturated sample of sixteen schools. One consists of twelve small schools (n = 1,284, 50.93 % female), and the other of one large school (n = 976, 48.46 % female). The findings indicated that reciprocity, choosing a friend of a friend as a friend, and smoking similarity increased friendship tie choice behavior, as did parental support. Parental monitoring interacted with choosing friends who smoke in affecting friendship tie choice, as at higher levels of parental monitoring, youth chose fewer friends that smoked. A parental home smoking context conducive to smoking decreased the number of friends adolescents chose. Peer influence and a parental home smoking environment conducive to smoking increased smoking, while parental monitoring decreased it in the large school. Overall, peer and parental factors affected the coevolution of friendship tie choice and smoking, directly and multiplicatively.

Keywords: Adolescence, Friendship, Social networks, Smoking, Peer influence, Stochastic Actor-Based models, Parental monitoring

Introduction

Peer and parental influences have long been noted as key socialization forces affecting adolescent development. Adolescence is a critical time period during which youth form friendships, and simultaneously engage in substance use behaviors such as cigarette smoking within their peer networks. It is also a time during which the initiation and subsequent fueling of long term smoking trajectories occur (Orlando et al. 2004), as most adult smokers begin in adolescence (Giovino et al. 1995). While valuable insights have been gained from past studies investigating the effects of peer and parental influences on adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior (Engels et al. 2004), studies have yet to consider the effects of multiple domains of parental influence in the context of dynamically modeled adolescent networks, in shaping the co-evolving processes of adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. Moreover, fewer studies yet have considered the possibility that peer network and parental influences might interact in affecting the outcomes of friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking. Guided by an ecological perspective on development (Bronfenbrenner 1979), indicating that contextual influences shape development, and Social Control Theory (Hirschi 1969; Nye 1958), positing the role of parents in deterring adolescent delinquent behavior, the current study contextualizes theoretically salient dimensions of parental influences within the dynamic landscape of adolescent friendship networks to disentangle the effects of peer network and parental influences on the interdependent and co-evolving processes of adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior.

Intuition from ecological models (Bronfenbrenner 1979) suggests that development is shaped by contextual influences stemming from youths’ nested environments. Drawing on this perspective, the peer and parental contexts are microsystems providing socialization influences which act as primary processes affecting adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking. Moreover, the ecological perspective suggests that influences in these microsystems interact in shaping development. Drawing on this perspective, the current study examines direct and multiplicative effects of both adolescent friendship network characteristics and processes with key dimensions of parental influences on adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. In addition, this study responds to a recent review (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011) indicating a need for greater understanding factors moderating the peer influence and adolescent smoking relationship. In what follows, we elaborate on salient characteristics and processes of adolescent friendship networks and three key dimensions of parental influences, the possibility for synergy between these peer and parental factors, and indicate their relevance to friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking.

Adolescent Friendship Networks

Adolescent friendships are an important dimension shaping development (Youniss and Smollar 1985). Adolescent friendship networks are a potent socialization context in which friendship tie choice and smoking co-evolve. Youth look to peers to gauge normative behaviors regarding substance use and many other behaviors. One key process that occurs within the friendship network context is peer influence, which is the propensity to alter one’s behavior such that it becomes more similar to ones’ friends. Peer influence is a notable factor shaping adolescent development (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011; Dishion and Tipscord 2011), and has also been implicated as a possible amplification mechanism for adolescent substance use (Dishion and Tipscord 2011), including adolescent smoking (Kobus 2003). Various theoretical perspectives provide supporting insights into how peer influence affects adolescent smoking, including Differential Association Theory (Sutherland 1947), Balance Theory (Heider 1958), and Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1977a). Various factors affect adolescents’ susceptibility to peer influence, including depressive symptoms (Allen et al. 2006), and other studies indicate gender specific effects in peer influence effects on smoking (Maxwell 2002; Wang et al. 1995).

Studies, however, have long noted that peer influence alone cannot explain the observed similarity among adolescent friends on smoking behavior (Hirschi 1969). Peer selection, the propensity for adolescents to select friends who are similar to themselves, is grounded in the principle of homophily (Lazarsfeld and Merton 1954) and is an alternative explanation for the observed similarity in behavior among adolescent friends. Adolescents tend to choose friends who are similar on multiple dimensions (Kandel 1978b), and close friends display similar substance use behaviors including smoking (Kirke 2004).

In addition to the network processes of peer influence and selection, other aspects of adolescent friendship networks are salient for understanding friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. First, indicators of degree (Robins 2013; Wasserman and Faust 1994), including in-degree and out-degree, are relevant for understanding these two processes. In-degree captures the number of incoming nominations for a network actor and reflects an actor’s popularity in a social system (Wasserman and Faust 1994). For instance, if Lauren receives 15 friendship nominations and Jim receives 4, Lauren is more popular than Jim. In-degree is also salient for adolescent smoking, as past studies generally find that youth with fewer social ties are more likely to smoke than their more socially integrated counterparts (Abel et al. 2002), with some exceptions indicating that popular youth are also likely to smoke (Valente et al. 2005). Out-degree indicates the number of nominations an actor sends to others and reflects an actor’s ability to communicate with those in the network, or the actor’s expansiveness. For example, if Lauren sends 10 friendship nominations and Jim sends 5, then Lauren can communicate more widely with others in the network. In-in degree assortativity describes the tendency to form ties with those who are similarly popular. For instance, if Lauren receives 15 friendship nominations, then she is likely to send nominations to individuals who have also received a similar number of nominations. In different ways, each of these indicators reflects prominence in a social network system.

Structural network properties—which describe linkages among network members—are useful for understanding adolescent friendship tie choice. Tie reciprocity, which indicates that a nomination between two network actors is mutually reciprocated, drives adolescent friendship formation (Younisis 1980), and signals close relationships. Indicators of local hierarchy in a network, including the transitive triplet and three cycle effects (see Wasserman and Faust 1994), indicate both triadic interdependency in the network structure and whether or not the network structure is hierarchical, and are also important to friendship tie choice. Transitivity indicates the extent to which an actor is ensconced in a tightly bound group. To illustrate the transitive triplet, if Lauren sends a friendship nomination to Jim and Jim sends one to Bill, and then Lauren is likely to also send one to Bill, creating a transitive triplet. To illustrate the three-cycle effect: if Jim sends a friendship nomination to Lauren, and Bill sends one to Jim, then Lauren will send one to Jim. Youth in such structures, especially in three-cycles, may exert strong influences on one another. Moreover, popular youth who occupy high social positions in the school social hierarchy may influence youth in lower positions, by displaying normative behaviors which less popular youth emulate. If popular youth smoke, then it’s likely that those less popular are likely to follow suit. Each of these structural network characteristics provides different insights into adolescent friendship tie choice behavior.

These degree and structural network characteristics are important features of many Stochastic Actor-Based models, which dynamically disentangle the endogenous factors of peer influence and peer selection, all of which are driven by network structure (Veenstra et al. 2013). These models account for the degree and structural network effects leading to network self-organization, and therefore need to be modeled in order to provide unbiased estimates of peer influence and selection parameters. Parsing apart and accurately characterizing these effects is important for informing adolescent smoking prevention programs (Mercken et al. 2012). The study of peer influence has been greatly advanced by such models, providing a way to simultaneously account for youths’ “microsocial” or proximal social interactions and changes in their network structure at the “macrosocial” level (Dishion 2013). Studies utilizing these models suggest the role of friendship network structure, peer influence, and peer selection in shaping adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior (Mercken et al. 2007). Extant studies utilizing such models however have not yet considered the co-evolution of adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior in the context of parental influences much beyond the effects of parental smoking. In sections to follow, we describe salient dimensions of parental influences for adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior, and consider the possibility that friendship network and parental influences might interact in affecting these outcomes.

Parental Influences, Adolescent Friendship Tie Choice and Adolescent Smoking

Parents are primary socialization agents influencing numerous aspects of adolescent development. Social Control Theory (Hirschi 1969; Nye 1958) suggests that parents exert control over children and affect their engagement in delinquent behavior in various ways, including via direct constraints on behavior such as monitoring. Other perspectives suggest that parents exert both direct and indirect effects on friendship tie choice behavior (Parke and Bhavnagri 1989), and encourage youths’ affiliation in prosocial peer groups (Parke and Ladd 1992). Past research has suggested the relevance of three dimensions of parental influence for friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking: parental support, parental monitoring, and parental smoking.

Adolescents view parents as vital sources of social support (Wills and Cleary 1996), even as youth transition to becoming increasingly independent and peer oriented (Giordano 2003). Parental support has been conceptualized as closeness, confiding, and the perceived support received from a parent in helping an adolescent deal with a problem (Wills and Cleary 1996). Parental support is critical for adolescent development and adaptation, as it has been positively associated with social competence, which is important in friendship formation (Rubin et al. 2004). Various theoretical perspectives, including Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1977b) and Attachment Theory (Bowlby 1969), also suggest the importance of parental support for adolescent friendship formation. Albeit through different mechanisms, these perspectives indicate that adolescents learn supportive behaviors from their parents which they then emulate in their own friendships, which affect friendship tie choice. Other research indicates that a lack of parental support predicts youths’ greater affiliation with deviant peers and delinquency throughout adolescence (Simons et al. 2001). In general, parental support has been negatively related to adolescent problem behaviors (Barber 1992; Baumrind 1991) including adolescent tobacco use (Wills and Cleary 1996). Overall, parental support appears critical for the development of social competencies which then affect adolescent friendship tie choice, including affiliation with delinquent peers, and subsequent smoking behavior.

Studies also note the salient role of parental monitoring in both adolescent friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking. Parental monitoring has been conceptualized in numerous ways, including as parental supervision of children, and communication between parents and youth (Kerr and Stattin 2000; Stattin and Kerr 2000). This construct has also been defined as a “a set of correlated parenting behaviors involving attention to and tracking of the child’s whereabouts, activities, and adaptations” (see page 61, Dishion and McMahon 1998). Past research indicates that high levels of parental monitoring appear to deter affiliation with drug using and otherwise delinquent adolescents (e.g., Brown et al. 1993; Knoester et al. 2006). Poorly monitored adolescents have a greater likelihood of using drugs, and of seeking out friends who use drugs (Steinberg et al. 1994). Poor parental monitoring has been related to engagement in problem behaviors including adolescent smoking (Ary et al. 1999), whereas studies find that strong parental monitoring protects against smoking stage progression among adolescents (Simons-Morton et al. 2004). Parental monitoring possibly exerts its influence via the increased awareness adults likely gain through monitoring their adolescents’ engagement in risk behaviors such as cigarette smoking and the subsequent enforcement of negative sanctions against those behaviors.

Parents can also influence friendship tie choice and smoking behavior via their own smoking behavior and the accessibility they provide to cigarettes in the household. We conceptualize the parental home smoking context as whether parents smoke and if cigarettes are available in the home. Having a parent who smokes has been positively related to adolescents choosing friends who smoke (Engels et al. 2004). Studies also indicate that parental smoking increases the risk of smoking initiation among adolescents (Engels et al. 2004). Parental smoking may exert its influence on adolescent smoking through various mechanisms, including the availability of cigarettes in the home environment, modeling, the internalization of parental smoking norms, and parents’ difficulty in enforcing sanctions against smoking when they themselves smoke. One study indicated that youth in homes with a complete ban on smoking were the least likely to be susceptible to smoking or to have experimented with smoking (Szabo et al. 2006). As such, parents are in a position to either facilitate or deter adolescent smoking, both through their own smoking behavior and sanctions within the home environment prohibiting or encouraging adolescent smoking.

Parental and Peer Influences on Friendship Tie Choice and Adolescent Smoking: Independent or Multiplicative Effects?

Various explanations have been put forth regarding the independent and relative influence of parents and peers in adolescents’ social worlds, some indicating these influences act independently, and others suggesting they interact in shaping adolescent behavior, specifically delinquency. Social Control Theory posits that parents exert a direct influence on adolescent delinquency, independent of peer influences (Hirschi 1969). Other work suggests that the family is a stronger influence on adolescents than peers (Coleman 1961). Delinquent behavior has also been explained as resulting from youths’ interactions with peers who serve as deviant role models (Sutherland and Cressey 1970). Other research casts parental and peer influences as complementary socialization forces (Younisis 1980), and some research suggests that peer and parental influences are linked in their effect on adolescent behavior (Knoester et al. 2006). Moreover, ecological models would suggest that influences stemming from adolescents’ peer and parental contexts might interact in shaping adolescent development (Bronfenbrenner 1979). In the current study, we adopt the perspective that peer and parental influences might act either independently or multiplicatively in affecting adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior.

To elaborate on the potential for interactions between the friendship network factors and parental influences under study, we turn first to the possibly multiplicative relationship between parental support and choosing friends who smoke for friendship tie choice, and secondly to the possibly multiplicative relationship between parental support and peer influence for smoking. The intuition for examining these moderating relationships is grounded in previous research indicating that various factors that likely affect parental support provision or parental support itself are instrumental in whether adolescents affiliate with friends who smoke, and in turn, the extent to which they are then influenced by these friends. For instance, one study found an interaction between parental involvement and peer affiliation among youth with problem behaving friends, as youth with uninvolved parents were at higher risk for initiating smoking (Simons-Morton 2002). Other research found that youth who became friends with other youth who smoked at a higher rate reported placing less value on spending time with parents (Urberg et al. 2003). Moreover, other research yet found that having parental support moderated the relationship between having delinquent friends and youths’ own delinquent behavior, as when support was low, the influence of delinquent peers was high (Poole and Regoli 1979). Taken together, these studies suggest that higher levels of parental involvement or support appear to lessen the likelihood that youth will befriend smokers, perhaps making it less likely that youth are then influenced by friends who smoke (see the two stage model of peer influence in Urberg et al. 2003), and begin smoking themselves.

We turn next to the possibly multiplicative relationship between parental monitoring and choosing friends that smoke for friendship tie choice, and to the possibly multiplicative relationship between parental monitoring and peer influence for smoking. These interactions are premised upon studies demonstrating that parental monitoring plays a role in the choice of friends with whom adolescents affiliate (Knoester et al. 2006), as studies find that high levels of parental monitoring deter affiliation with drug using adolescents (e.g., Bogenschneider et al. 1998; Brown et al. 1993). Similarly, other research suggests that both the quality and frequency of parental smoking-specific communication was positively related to youths’ selective affiliation with non-smoking friends (Leeuw et al. 2008). Consistent with these studies, other research found that parental monitoring had a direct and protective effect against smoking progression among adolescents; in addition, it indirectly affected smoking by inhibiting increases in the acquisition of friends who smoke (Simons-Morton et al. 2004). Other work found that both inadequate parental monitoring and association with deviant peers at a later time period predicted subsequent tobacco use among adolescents (Biglan et al. 1995). In general, these studies highlight the direct role of parental monitoring in decreasing adolescent smoking, and as well its indirect role in attenuating youths’ association with friends who smoke.

We also consider the possibly multiplicative relationship between the parental home smoking context and choosing friends that smoke for friendship tie choice, and the possibly multiplicative relationship between parental home smoking context and peer influence for smoking. The intuition underlying such interactions is based upon research suggesting that parental smoking affects adolescent friendship tie choice, as one study found that adolescents with parents who smoked were likely to befriend youth who smoked (Engels et al. 2004). Moreover, Engels et al. (2004) assert that the influence of parental smoking may be underestimated if the ways in which parental smoking influences adolescents’ functioning in friendships are not considered. Other research highlights the importance of the home smoking environment for adolescent smoking, as one study found that a having a smoking ban in the home moderated the relationship between parental smoking and smoking uptake stage among adolescents, with the influence of home smoking bans strongest when neither parent smoked (Szabo et al. 2006). Indeed, youths’ exposure to parental smoking and sanctions in the home which affect smoking can play a key role in whether youth select and then are influenced by friends who smoke, which will in turn affect their own smoking behavior.

Lastly, based on intuition from ecological models (Bronfenbrenner 1979), we examine the relationships under study across two types of school contexts: one large school and a set of small schools. School size is an important contextual factor for adolescent development, with large and small school contexts affording differential opportunities for developing social competencies and responsibilities, making friends, and engaging in extracurricular activities, among many other differences (Garbarino 1980). Schools have also been noted as a key context in affecting adolescent substance use (Bond et al. 2007).

Current Study

This study considers adolescent friendship network and parental influences shaping adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. We utilize a Stochastic Actor-Based Model approach to dynamically examine friendship network characteristics and processes with key dimensions of parental influences acting on the co-evolving processes of friendship tie choice and smoking among youth in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a large nationally representative study of high schools in the United States. We utilize two samples: one comprised of 12 small high schools and another of one large high school. Turning first to the network factors theoretically salient for friendship tie choice, we hypothesize that reciprocity, the degree based measures, and structural network factors will increase the number of friends youth choose. Based on past literature, we also anticipate a positive relationship between smoking similarity (i.e., selection effect) and friendship tie choice. We expect both parental support and parental monitoring will positively relate to friendship tie choice and that a home smoking environment conducive to smoking will negatively relate to friendship tie choice. We also hypothesize that the parental factors under study will interact with choosing friends who smoke in affecting friendship tie choice. We expect negative interactions for both parental support and parental monitoring with choosing friends who smoke, and a positive interaction for the parental home smoking environment.

Turning next to the factors predicting adolescent smoking, guided by past literature, we hypothesize a positive relationship between peer influence and smoking, and a negative relationship between in-degree centrality and smoking. Premised upon research relating the parental influences under study and adolescent smoking, we hypothesize a negative relationship between both parental monitoring and parental support and smoking, and a positive relationship between a parental home environment condoning smoking and adolescent smoking. Moreover, we expect that the parental influences under study will interact with peer influence in relation to smoking, and hypothesize a negative interaction for both factors of parental support and parental monitoring, and a positive interaction for parental home smoking environment. To our knowledge, studies have not yet examined the complement of parental influences under study or their interactions with the peer network effects in context of dynamic adolescent friendship networks for the outcomes of friendship tie choice and smoking.

Lastly, we expect the patterning of the relationships under study to differ across the two samples under study. We expect stronger peer than parental effects to operate in the smaller versus larger school, given that in the smaller school contexts, youth may have more chances to form stronger bonds with friends through increased social participation and engagement in social roles and extracurricular activities smaller school environments may afford (Garbarino 1980). We also expect that the peer and parental factors will interact to affect the outcomes under study in both samples.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data utilized in this study are from three surveys conducted as part of the National Study of Adolescent Health of students in grades 7–12, conducted in 1994–1995 and 1995–1996 (see Harris et al. 2009). The current study included data from the Wave 1 interviews occurring in school (i.e., “In-School Survey”), the wave 2 interviews occurring at home 6 months later (i.e., wave 1 “In-Home Survey”), and the wave 3 interviews also occurring at home one year later (i.e., wave 2 “In-Home Survey”). Over the three waves, information regarding the social and demographic characteristics of the adolescents, their parents, and adolescents’ health risk behaviors including smoking were collected. We use network data from a saturated sample of sixteen schools (Harris et al. 2009). Of the sixteen schools (n = 4,618), two were not useable (n = 180), due to either high student turnover (i.e., a special education school) or an administrative error which prohibited data linkage by identification number. Of the fourteen remaining, we excluded the largest school (n = 2,178), as its size posed estimation challenges for a three-wave analysis using the RSIENA statistical program. We created two samples: the first is the second largest school (n = 976), referred to as “Jefferson High” a rural predominantly White school, see Bearman et al. (2004). The second sample consisted of twelve small schools (n = 1,284), each with fewer than 200 students enrolled see (Cheadle and Goosby 2012; Cheadle and Schwadel 2012). The decision to create the two samples was based on the fact that the Jefferson High sample may have a different macro setting than the small schools, and moreover, its large size would statistically overwhelm the estimates for the small schools. Given the lack of comparability between samples, we do not attempt a formal statistical comparison of relationships across samples. To account for possible variation across the twelve schools, we also estimated ancillary models along several key dimensions: (1) urban, suburban versus rural schools, (2) public versus private schools, and (3) single race versus multiple race schools. The parameters were quite similar in these separate models and the interaction effects between dummy variables for these contextual variables with key smoking effects were not significant, suggesting that the co-evolution of friendship tie choice and smoking behavior was similar across different types of schools.

To account for missing network data at wave 1, we employ the latent missing data approach (Handcock 2002). This approach uses an exponential random graph model (ERGM) to estimate the probability that a tie exists among the missing network data in the first wave, and then imputes these probabilities accordingly. Missing data for later waves is handled by a built in feature in RSIENA, treating them as noninformative (see Ripley et al. 2014).

Measures

Dependent Variables

Smoking

At wave 1, the item assessing smoking is: “During the past 12 months, how often did you smoke cigarettes?” (0 = never; 1 = once or twice; 2 = once a month or less; 3 = 2 or 3 days a month; 4 = once or twice a week; 5 = 3–5 days a week; 6 = nearly every day). At waves 2 and 3, a different question was asked: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” measured continuously (0 = no days to 30 = 30 days). The variable we utilized across all three waves re-categorizes the response categories across the two items such that they match the category framing across waves, which include: (0 = never, 1 = 1–3 days, 2 = 4–21 days, 3 = 22 or more days).

Friendship Tie Choice

To construct the adolescent friendship networks, each student was asked to nominate up to five female and five male best friends in his or her school. This information was used to create the school-specific friendship network; the 12 small school networks were combined to form one large network. Structural zeroes were used to account for no ties allowed between adolescents across different schools (see page 81, Ripley et al. 2014). The dependent variable for friendship tie choice is the presence or absence of a tie.

Independent Variables

Friendship Network Effects

We control for endogenous friendship network effects affecting friendship tie choice by including several friendship network measures (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect for modeling friendship tie choice

| Effect | Friendship Tie Choice Statistic | Tie Change | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendship Tie Choice Rate parameter | - | The expected number of change opportunities for each respondent during each period | ||

| Out-degree (density) | ∑j xij | General tendency to choose a friend | ||

| Reciprocity | ∑j xijxji | Tendency to have reciprocated (mutual) friendships | ||

| Transitive triplets | ∑j,h xijxihxjh | Tendency to become the friend of a friend's friend | ||

| Three cycles | ∑j,h xijxjhxhi | Tendency to choose a friendship nominator's nominator as a friend | ||

| In-degree popularity | ∑j xijx+j |  |

Tendency to choose a popular adolescent as a friend | |

| In-in degree assortativity (square root) | Tendency to choose an adolescent with a similar in-degree as a friend | |||

| Smoking alter (friend) | ∑j xij(zj − z̄) | Main effect of a potential friend’s smoking behavior on friendship tie choice | ||

| Respondent (ego) covariates: smoking, parental variables | ∑j xij(zi − z̄) (∑j xij(vi − v̄)) | Main effect of respondent's or parent behavior on friendship tie chice | ||

| Smoking similarity, gender similarity, grade similarity, parental education similarity | −∑j xij|zi − zj|/∑j xij (−∑j xij|vi − vj|/∑j xij) | Tendency to have ties to similar others (selection Effect) | ||

| Moderating (interaction) effect | ∑j xij(vi −v̄)(zj − z̄) | Tendency for those with higher values of covariates to choose adolescents that smoke more as ties (+effect) or the tendency for those with higher values of covariate to choose adolescents that smoke less as friends (−effect) |

low score (negative)

low score (negative)  high score (positive)

high score (positive)  arbitrary score

arbitrary score

Friendship Tie Choice Rate parameter

The expected number of change opportunities for each respondent in each period.

Out-degree

This is an indicator of the general tendency to send friendship nominations, and reflects the actor’s expansiveness or salience in a network (Wasserman and Faust 1994).

In-degree

This a measure of the number of friendship tie nominations one receives and reflects a dimension of prestige, specifically popularity.

In-in-degree assortativity (square root)

This is a measure of the tendency to choose a similarly popular adolescent.

Both In-degree and In-in-degree assortativity indicate an adolescent’s tendency towards preferential attachment, in either choosing popular youth (In-degree) or choosing similarly popular adolescents (In-in-degree assortativity).

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is an indicator of the tendency to have mutually reciprocated friendships among any two adolescents. Reciprocity signals close, symmetric friendships, and it is likely a key dimension of social cohesion (Wasserman and Faust 1994).

Transitive triplets

This measure captures the tendency to choose a friend of a friend as a friend.

Three-cycles

This measure captures the tendency to choose a friendship nominator’s nominator as a friend. Both transitive triplets and three-cycles are indicators of triadic closure, meaning that a friend of a friend is also a friend (Wasserman and Faust 1994). The difference between these two indicators lies in the directionality of the ties between the three actors comprising these indicators.

Limited nominations

Due to an administrative error, some participants could only choose one male friend and one female friend during the wave 1 In-Home and wave 2 In-Home surveys. We account for this with a limited nomination variable (measured as: −1 = changed from full to limited nominations, 0 = no change, and +1 = changed from limited to full nominations) in the friendship tie choice equations.

Regarding the role of smoking behavior in predicting friendship tie choice, we include three measures (see Table 1):

Smoking alter (friend)

This indicator captures the effect of a friend’s smoking behavior on an adolescent’s friendship tie choice.

Smoking ego (respondent)

This indicator captures the effect of the respondent’s own smoking behavior on friendship tie choice.

Smoking similarity

This indicator captures the selection effect, which is the tendency to choose friends with similar smoking behavior.

We also capture homophily along three covariates, gender, grade and parental education:

Gender similarity

This indicator captures the tendency to choose friends of the same gender, indicating homophily on gender.

Grade similarity

This indicator captures the tendency to choose friends of the same grade, indicating homophily on grade.

Parental education similarity

This indicator captures the tendency to choose friends whose parents have a similar educational background. This is an indicator of homophily on family socio-economic status.

Smoking Behavior Effects

To capture how smoking behavior changes over time, we include several measures (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects for modeling smoking behavior

| Effect | Smoking Behavior Statistic | Smoking Behavior Change |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking rate parameter | - | The expected number of change opportunities for each respondent in each period | |

| Linear shape | zi − z̄ | The basic drive toward high values of smoking | |

| Quadratic shape | (zi − z̄)2 | The self-reinforcing function of smoking behavior | |

| In-degree | (zi − z̄)x+i |  |

The effect of being popular on smoking behavior |

| Similarity | −∑jxij|zi − zj| / ∑jxij |  |

Main effect of behavior similarity between respondent and each alter (Peer Influence Effect) |

| Covariates: parental influences, gender, depressive symptoms, | (zi − z̄)vi | Main effect of covariate on smoking | |

| Moderating (interaction) effect | (zi − z̄)vi[−∑jxij|zi − zj| / ∑jxij] | Tendency for an adolescent with higher value of covariate to have a higher propensity to match alters' behavior |

low score (negative)

low score (negative)  high score (positive)

high score (positive)  arbitrary score

arbitrary score

Smoking rate parameter

The expected number of change opportunities for each respondent in each period.

Smoking shape parameters

The linear and quadratic shape parameters model the effect of current smoking behavior on future smoking behavior.

In-degree

This indicator captures the effect of being a popular student on levels of smoking behavior.

Smoking behavior similarity

This is the peer influence effect. It captures the tendency for students to change their smoking behavior such that it matches the average smoking behavior of their friends.

Parental Influences

Parental support

Parental support was estimated as a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with good model fit (Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .05, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .98) and we computed a standardized factor score (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). It is based on multiple items, including whether an adolescent has talked about a personal problem with their parents (0 = no, 1 = yes), and five questions asking respondents to separately rate their mother and father to be: (1) warm and loving, (2) good communicators, (3) part of an overall “good relationship” (the response categories for all three items are: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree); 4) close, and 5) caring (with the response categories for the last two items being: 1 = not at all, 2 = very little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = very much).

Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring was estimated as a CFA (the RMSEA of .06 and the CFI of .97 suggested a good fit), and we computed a standardized factor score. It combines eight questions related to the adolescent’s autonomy, with the first five related to whether the adolescent was allowed to decide: (1) their weekend curfew, (2) who they hang around with, (3) what they watched on TV, (4) how much TV they watched, and (5) their weekday bedtime (0 = no and 1 = yes, for all 7 items). The other three questions measuring parental monitoring asked whether the parent was present when the adolescent came home from school (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = some of the time, 3 = most of the time, 4 = always, 5 = they brought the student home from school), went to bed (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = some of the time, 3 = most of the time, 4 = always) and ate dinner (0–7 days per week).

Parental home smoking environment

Parental home smoking environment was measured by summing dichotomous measures of parent smoking behavior and cigarette availability at home.

Control Variables

Gender (Clayton 1991), depressive symptoms (Steuber and Danner 2006), and grade (Kelder et al.1994) have all been related to adolescent smoking. We included a measure of gender (0 = male, 1 = female). Depressive symptoms is measured as a factor score (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), and is based on 19 ordinal items taken (with a few changes) from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). Age is captured as current grade.

Analytical Strategy

To explore the joint evolution of friendship tie choice and smoking behavior, we apply the Stochastic Actor-Based model developed by Snijders and collaborators (Snijders 2011; Snijders et al. 2010), found in the R-based Simulation Investigation for Empirical Network Analysis (RSIENA) software package (see Ripley et al. 2014). The Stochastic Actor-Based model assumes that observed network data arise as cross-sectional samples from a latent continuous time Markov process, in which possible ties and network actors’ behavior constitute the state space, and simulates this latent process with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm. This allows modeling feedback relationships between smoking and network structure. At each micro-step in the evolution of the network, an actor re-evaluates his or her relationships and chooses to form a new tie, keep an existing tie, or extinguish a tie to optimize his or her own objective function. Concurrently, at each micro-step, a behavioral decision regarding cigarette smoking is modeled similarly, with an actor deciding to increase, stay the same, or decrease his or her level of smoking behavior. The objective function of friendship tie choice and that of smoking behavior changes are estimated simultaneously in a set of interdependent equations. The model also includes rate functions which capture the expected frequency of network tie decisions or smoking behavior decisions made between observation points. In the initial analysis model, we included the main effects of the three parental variables in both the friendship tie choice and smoking equations. In subsequent models, we added interaction terms of each parental variable and alter smoking behavior in the friendship tie choice equation, and interaction terms of each parental variable and smoking behavior similarity (i.e., the peer influence effect) in the smoking behavior equation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The smoking behavior and network descriptive statistics for both study samples are summarized in Table 3. Nearly 64 % of students reported they were non-smokers at wave 1 in the small schools, and this percentage increased to almost 76 % at wave 2, and then decreased to about 64 % in wave 3. In “Jefferson High”, 42 %were non-smokers at wave 1, which rose to 53 % at wave 2 before falling to 45 % at wave 3. At the other extreme, about 15 % were heavy-smokers at wave 1 in the small schools, which fell to nearly 12 % at wave 2 before increasing to 18 % at the last time point. “Jefferson High” had more smoking, with 28, 26, and 32 % heavy smokers at the three waves, respectively.

Table 3.

A: Smoking and network descriptive statistics, B: time invariant covariates

| 12 Small schools (n = 1,284) | Jefferson high (n = 976) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 |

Wave 2 |

Wave 3 |

Wave 1 |

Wave 2 |

Wave 3 |

|||||

| A | ||||||||||

| Smoking (past 30 days, %) | ||||||||||

| 0 = never | 63.86 | 75.78 | 63.94 | 42.01 | 53.17 | 45.39 | ||||

| 1 = 1–3 days | 15.89 | 5.30 | 9.66 | 21.31 | 9.12 | 11.68 | ||||

| 2 = 4–21 days | 4.91 | 7.16 | 8.25 | 9.02 | 11.58 | 10.55 | ||||

| 3 = 22 or more days | 15.34 | 11.76 | 18.15 | 27.66 | 26.13 | 32.38 | ||||

| Network statistics | ||||||||||

| Out-going ties | 6,671 | 2,449 | 2,704 | 6,063 | 3,713 | 2,484 | ||||

| Reciprocity index | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.42 | ||||

| Transitivity index | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.21 | ||||

| Jaccard index | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Limited nominations (%) | 0 | 36.76 | 0.39 | 0 | 4.82 | 0.41 | ||||

| 12 small schools (n = 1,284) | Jefferson High (n = 976) | |

|---|---|---|

| B | ||

| In-school survey | ||

| Female (%) | 50.93 | 48.46 |

| Grade level (%) | ||

| 7th grade | 23.99 | 0.00 |

| 8th grade | 25.00 | 0.00 |

| 9th grade | 14.25 | 28.80 |

| 10th grade | 12.69 | 28.48 |

| 11th grade | 12.07 | 21.72 |

| 12th grade | 12.00 | 21.00 |

| Parent education level (%) | ||

| Less than high school | 6.46 | 5.22 |

| High school | 39.25 | 38.32 |

| Some college or trade school | 31.70 | 36.48 |

| Graduate of college/university | 22.59 | 19.98 |

| Wave 1 In-Home survey | ||

| Depressive symptoms, mean (sd) | −0.11 (0.46) | 0.00 (0.53) |

| Parental support, mean (sd) | 0.06 (0.25) | −0.04 (0.29) |

| Parental monitoring, mean (sd) | 0.02 (0.12) | −0.04 (0.10) |

| Home smoking environment, mean (sd) | 1.14 (0.81) | 1.42 (0.73) |

The reciprocity index is the proportion of ties that were reciprocal. The transitivity index is the proportion of 2-paths (ties between AB and BC) that were transitive (ties between AB, BC, and AC). The Jaccard index measures the network stability between consecutive waves

In the small school sample, about 45 % of ties were reciprocated at wave 1, whereas 34 % were in “Jefferson High.” Whereas reciprocation fell over time in the smaller schools, it increased in “Jefferson High.” In part, this may be due to limited nominations in the smaller schools (i.e., about 37 % of students were limited to nominate only one male and one female best friend in wave 2), as well as graduation, attrition, non-response, and missing network data. The transitivity index captures the tendency for individuals who share a common friend to be a friend, and was relatively stable during the study, although stronger in the smaller schools (29–35 %) compared to “Jefferson High” (18–21 %). The Jaccard Index measures network stability between consecutive waves. There was also a high turnover in friendship ties, as 15–18 % of ties persisted between the first and the second time periods in the samples, and 21–22 % of ties persisted between the second and the third time periods. Ripley et al. (2014) point out that based on past experience with Stochastic Actor-Based modeling, there can be estimation difficulties when the Jaccard index is lower than 0.2, especially if it is less than 0.1. In this study we encountered no such estimation problems. Furthermore, the fact that the results were similar when using just waves 2–3 (when the Jaccard exceeded .2), along with the fact that results of a post hoc time heterogeneity test for the models found no evidence that the co-evolution of friendship networks and smoking behavior was significantly different across the two time periods, suggests little evidence of estimation problems. Moreover, Simpkins et al. (2013) show that for larger networks a lower Jaccard index value can be tolerated. The descriptive statistics of the covariates are reported in Table 3.

Social Network Analyses

Friendship Tie Choice Equation

As shown in the friendship tie choice equations of Table 4, similarity in smoking behavior increased friendship tie choice in the twelve school sample (b = 0.23, p < .01), in model 1. Similarity in smoking also increased friendship tie choice in the “Jefferson High” sample (b = 0.26, p < .001), see Table 5. Additionally, adolescents were more likely to form a tie with another adolescent if the tie was reciprocated (b = 1.85, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = 2.48, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”), part of a transitive triplet (b = .32, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = .55, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”) or the alter already had many in-coming ties (b = .09, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = .05, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”). Adolescents were less likely to form a tie if they had higher out-degree (b = −1.85, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = −2.61, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”), or if it created more three-cycles (b = −.16, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = −.46, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”). The positive transitive triplet effect along with a negative three-cycle effect implies a tendency toward local hierarchy. The negative effect for in-in degree assortativity (square root) (b = −.13, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = −.06, p < .05 in “Jefferson High”) implies that adolescents with low in-degrees were more likely to nominate those with high in-degrees, which is consistent with a preferential attachment mechanism. Students were more likely to nominate others as best friends if they had the same gender (b = .22, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = .21, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”), were in the same grade (b = .53, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = .43, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”), or if their parents had similar educational background (b = .08, p < .001 in the small schools, and b = .05, p < .01 in “Jefferson High”). Furthermore, the positive smoking alter effect (b = .12, p < .05 in the small schools, and b = .07, p < .001 in “Jefferson High”) indicates that those smoking more frequently were more popular than those smoking less frequently.

Table 4.

Friendship tie choice and smoking models for 12 schools in one large network (n = 1,284)

| Effect name | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Friendship tie choice | ||||||||

| Constant friendship rate (period 1) | 12.56*** | 0.68 | 12.46*** | 1.12 | 12.39*** | 0.32 | 12.38*** | 0.31 |

| Constant friendship rate (period 2) | 6.96*** | 0.24 | 6.94*** | 0.36 | 6.91*** | 0.32 | 6.92*** | 0.26 |

| Out-degree (density) | −1.85*** | 0.06 | −1.84*** | 0.06 | −1.82*** | 0.07 | −1.80*** | 0.06 |

| Reciprocity | 1.85*** | 0.06 | 1.86*** | 0.11 | 1.87*** | 0.09 | 1.87*** | 0.07 |

| Transitive triplets | 0.32*** | 0.03 | 0.33*** | 0.02 | 0.33*** | 0.02 | 0.33*** | 0.03 |

| 3-cycles | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.16*** | 0.05 | −0.16*** | 0.04 | −0.16** | 0.06 |

| In-degree—popularity | 0.09*** | 0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.01 |

| In-in degree^(1/2) assortativity | −0.13*** | 0.03 | −0.14*** | 0.02 | −0.15*** | 0.02 | −0.15*** | 0.02 |

| Gender similarity | 0.22*** | 0.03 | 0.23*** | 0.05 | 0.22*** | 0.04 | 0.22*** | 0.03 |

| Parental education similarity | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.08*** | 0.02 |

| Grade similarity | 0.53*** | 0.02 | 0.53*** | 0.04 | 0.53*** | 0.03 | 0.53*** | 0.02 |

| Parental support ego (respondent) | 0.26* | 0.11 | 0.32* | 0.16 | 0.27** | 0.10 | 0.27** | 0.09 |

| Parental monitoring ego (respondent) | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.24 | 0.21 | −0.38 | 0.24 | −0.25 | 0.16 |

| Home smoking environment ego (respondent) | −0.11*** | 0.02 | −0.11*** | 0.03 | −0.12*** | 0.03 | −0.15*** | 0.03 |

| Smoking alter | 0.12* | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.11** | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Smoking ego (respondent) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Smoking similarity (Selection effect) | 0.23** | 0.09 | 0.22** | 0.07 | 0.23*** | 0.05 | 0.22*** | 0.05 |

| Limited nomination ego (respondent) | −0.86*** | 0.05 | −0.86*** | 0.07 | −0.87*** | 0.05 | −0.87*** | 0.03 |

| Parental support ego × smoking alter | −0.15 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Parental monitoring ego × smoking alter | −0.40 | 0.44 | ||||||

| Home smoking environment ego × smoking alter | 0.05 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Smoking behavior | ||||||||

| Rate smoking behavior (period 1) | 12.12*** | 2.38 | 10.69** | 4.09 | 11.65*** | 1.46 | 11.56*** | 1.87 |

| Rate smoking behavior (period 2) | 25.67*** | 4.02 | 22.53*** | 3.59 | 24.91*** | 5.71 | 24.64*** | 2.40 |

| Smoking behavior linear shape | −2.55*** | 0.32 | −2.42*** | 0.59 | −2.55*** | 0.52 | −2.59*** | 0.34 |

| Smoking behavior quadratic shape | 0.79*** | 0.03 | 0.78*** | 0.04 | 0.79*** | 0.03 | 0.79*** | 0.03 |

| Smoking behavior in-degree | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Smoking behavior similarity (Influence effect) | 0.58*** | 0.15 | 0.62** | 0.19 | 0.62*** | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.56 |

| Effect from gender (female = 1) | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| Effect from grade | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Effect from depressive symptoms | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Effect from home smoking environment | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.24*** | 0.04 | 0.22*** | 0.03 | 0.29*** | 0.14 |

| Effect from parental support | −0.15 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.54 | −0.16 | 0.11 | −0.15† | 0.09 |

| Effect from parental monitoring | −0.36* | 0.18 | −0.43* | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.84 | −0.36† | 0.19 |

| Effect from parental support × similarity | 1.56 | 1.45 | ||||||

| Effect from parental monitoring × similarity | 2.04 | 2.77 | ||||||

| Effect from home smoking environment × similarity | 0.26 | 0.38 | ||||||

Two-sided p < .1;

Two-sided p < .05;

Two-sided p < .01;

Two-sided p < .001

Table 5.

Friendship tie choice and smoking models for Jefferson High (n = 976)

| Effect name | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Friendship tie choice | ||||||||

| Constant friendship rate (period 1) | 23.64*** | 1.86 | 23.51*** | 1.03 | 23.54*** | 0.78 | 23.59*** | 0.80 |

| Constant friendship rate (period 2) | 15.40*** | 0.63 | 15.34*** | 0.63 | 15.36*** | 0.59 | 15.38*** | 0.84 |

| Out-degree (density) | −2.61*** | 0.06 | −2.60*** | 0.06 | −2.59*** | 0.07 | −2.57*** | 0.06 |

| Reciprocity | 2.48*** | 0.09 | 2.48*** | 0.08 | 2.48*** | 0.05 | 2.48*** | 0.06 |

| Transitive triplets | 0.55*** | 0.04 | 0.55*** | 0.02 | 0.55*** | 0.02 | 0.55*** | 0.02 |

| 3-cycles | −0.46*** | 0.06 | −0.46*** | 0.04 | −0.46*** | 0.05 | −0.46*** | 0.04 |

| In-degree—popularity | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 0.05*** | 0.01 |

| In-in degree^(1/2) assortativity | −0.06* | 0.03 | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.06*** | 0.01 | −0.06*** | 0.02 |

| Gender similarity | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.02 | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.03 |

| Parental education similarity | 0.05** | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 0.05*** | 0.01 |

| Grade similarity | 0.43*** | 0.02 | 0.43*** | 0.02 | 0.43*** | 0.02 | 0.43*** | 0.02 |

| Parental support ego (respondent) | 0.09* | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.09* | 0.04 | 0.08* | 0.04 |

| Parental monitoring ego (respondent) | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.57* | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Home smoking environment ego (respondent) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Smoking alter | 0.07*** | 0.02 | 0.07* | 0.03 | 0.06* | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Smoking ego (respondent) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Smoking similarity (Selection effect) | 0.26*** | 0.03 | 0.25*** | 0.03 | 0.25*** | 0.03 | 0.25*** | 0.04 |

| Limited nomination ego (respondent) | −0.71*** | 0.08 | −0.71*** | 0.08 | −0.71*** | 0.06 | −0.71*** | 0.06 |

| Parental support ego × smoking alter | −0.04 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Parental monitoring ego × smoking alter | −0.36* | 0.17 | ||||||

| Home smoking environment ego × smoking alter | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Smoking behavior | ||||||||

| Rate smoking behavior (period 1) | 9.00*** | 1.59 | 8.93*** | 1.09 | 8.60*** | 1.12 | 9.13*** | 1.02 |

| Rate smoking behavior (period 2) | 14.56*** | 1.65 | 14.53*** | 2.57 | 14.43*** | 2.18 | 14.54*** | 3.58 |

| Smoking behavior linear shape | −1.77*** | 0.37 | −1.75*** | 0.44 | −1.49*** | 0.42 | −2.17*** | 0.51 |

| Smoking behavior quadratic shape | 0.67*** | 0.03 | 0.68*** | 0.03 | 0.67*** | 0.02 | 0.68*** | 0.03 |

| Smoking behavior in-degree | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Smoking behavior similarity (Influence effect) | 0.80*** | 0.15 | 0.83*** | 0.13 | 0.73*** | 0.13 | 0.64 | 1.05 |

| Effect from gender (female = 1) | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Effect from grade | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03† | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Effect from depressive symptoms | 0.13** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.13** | 0.05 |

| Effect from home smoking environment | 0.12*** | 0.03 | 0.12*** | 0.03 | 0.12*** | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Effect from parental support | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Effect from parental monitoring | −0.17 | 0.24 | −0.16 | 0.21 | −0.19 | 0.35 | −0.09 | 0.38 |

| Effect from parental support × similarity | 0.53 | 1.17 | ||||||

| Effect from parental monitoring × similarity | −2.00 | 1.75 | ||||||

| Effect from home smoking environment × similarity | 0.12 | 0.79 | ||||||

Two-sided p <.1;

Two-sided p <.05;

Two-sided p <.01;

Two-sided p <.001

Some main effects for the parental measures were also observed for friendship tie choice. Those receiving more parental support tended to name more best friends, although this effect was much stronger in the smaller schools (b = .26, p < .05) than in “Jefferson High” (b = .09, p < .05). Although those coming from a home conducive to smoking tended to nominate fewer best friends over time in the smaller schools (b = −.11, p < .001), no such effect was present in “Jefferson High”. Parental monitoring, however, did not have a statistically significant effect on friendship tie choice.

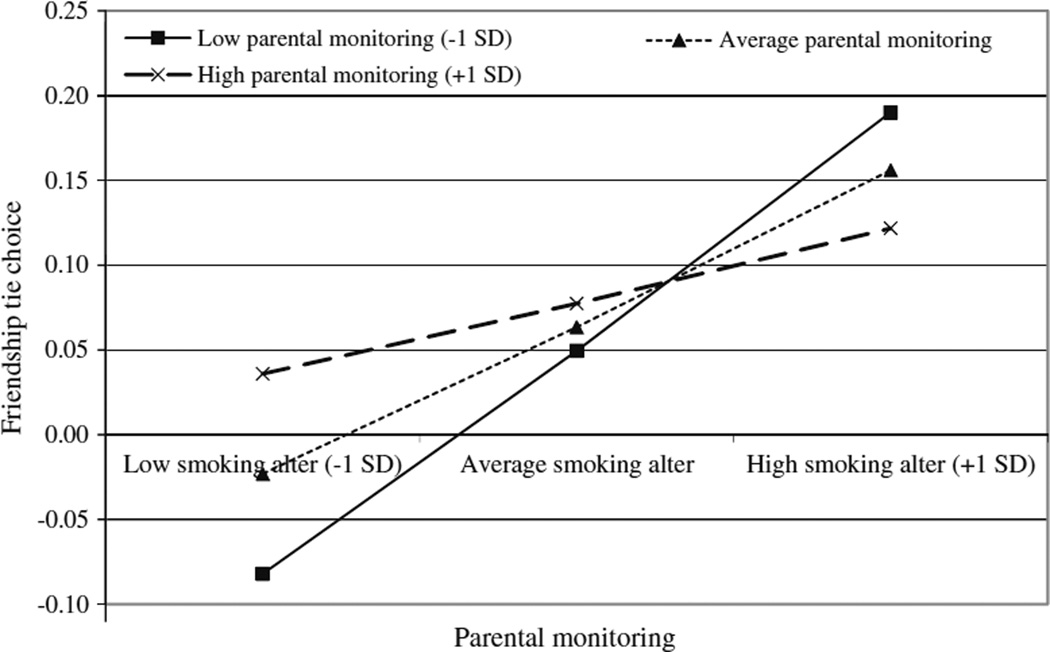

Although the interaction effects for the parental measures are in the expected directions, only parental monitoring attained statistical significance in the “Jefferson High” sample (b = −.36, p < .05) (Fig. 1). Thus, whereas those with more parental monitoring chose fewer smokers, this effect was only significant in “Jefferson High” (although the magnitude of the coefficient was similar in both samples). Although those with more parental support choose fewer smokers, and those from a home environment conducive to smoking choose more smokers, these effects did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Fig. 1.

Model of the interaction of parental monitoring ego and smoking alter on friendship tie choice for Jefferson High (n = 976)

Smoking Behavior Equation

As shown in the smoking behavior equations, there is a significant positive similarity effect (peer influence effect) on smoking behavior in both the smaller schools (b = 0.58, p < .001) and “Jefferson High” (b = 0.80, p < .001), meaning that adolescents were likely to adopt the smoking behavior of their friends (i.e., as the smoking levels of their friends increased, so did their own smoking propensity over time). The evolution of smoking behavior was not found to vary with respondent’s in-degree, gender, or grade. Those with more depressive symptoms smoked more over time in “Jefferson High” (b = 0.13, p < .01), but not in the smaller schools. There was evidence of direct effects of parental influences on smoking. Those with higher levels of parental monitoring engaged in less smoking behavior over time, although the effect was only statistically significant in the smaller schools (b = −.36, p < .05). Those with a home environment conducive to smoking increased smoking behavior over time, and this effect was even stronger in the smaller schools (b = .21, p < .001) compared to “Jefferson High” (b = .12, p < .001). Parental support, however, did not have a statistically significant effect on smoking behavior over time.

None of the interaction effects of the parental constructs and peer influence were statistically significant. The effect of the home smoking environment was positive in both networks, but was not significant. Parental monitoring only was negative but not significant in the large school, and the parental support interaction was not statistically significant. Thus, the peer influence effects for adolescent smoking in both the twelve small schools and “Jefferson High” did not vary in strength by their parental contexts.

Discussion

Premised upon insight from ecological perspectives on development (Bronfenbrenner 1979) and Social Control Theory (Hirschi 1969; Nye 1958) the present study considers three theoretically salient dimensions of parental influences for adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking within the rich conceptual context of dynamically modeled adolescent networks. It does so to disentangle the influence of these peer and parental factors as they affect friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. Contextualizing these parental influences within dynamically modeled adolescent friendship networks allows for parsing apart the effects of these parental influences from the simultaneous effects of key network processes including peer influence and selection, degree and structural network characteristics, and homophily effects. In addition, while studies investigating the co-evolution of friendship tie choice behavior and smoking using Stochastic Actor-Based models have yielded valuable insights (Dishion 2013), and as well, other research examining peer and parental influences on friendship tie choice and smoking behavior (Engels et al. 2004; Knoester et al. 2006), the current study moves beyond this work as we are not aware of any research examining the set of parental influences under study nor their interactions with the peer network processes under study as they affect the co-evolution of friendship tie choice behavior and smoking. Using two longitudinal samples of the friendship networks of adolescents in grades 7 through 12, the current study examined the co-evolution of adolescent friendship tie choice and smoking within the context of friendships network characteristics and processes and three domains of parental influences.

Overall, we find evidence for many of our study hypotheses, which in turn supports the ecological contention upon which our study is premised (Bronfenbrenner 1979), that contextual influences from the peer and parental microsystems shaped friendship tie choice and adolescent smoking behavior directly, and some evidence of a multiplicative relationship between these factors. In general, our findings are suggestive of a friendship network and parental milieu wherein tie reciprocity, the network factors of transitive triplets and three-cycles indicating position in the local hierarchy, parental support, and homophily effects including smoking similarity, grade similarity, gender similarity, and the interaction of parental monitoring and choosing friends who smoked were key drivers of friendship tie choice behavior. Of the factors predicting adolescent smoking, we found that peer influence increased smoking behavior, suggesting that the more youths’ friends smoked, the more youth were likely to smoke. Some of the parental influences under study affected smoking, as parental monitoring had a negative effect on smoking in the small school sample, and having a parental home smoking context conducive to smoking led to more smoking in both samples. Overall, these findings suggest both direct and multiplicative effects of the peer and parental influences on the outcomes under study.

Friendship Tie Choice

Our findings indicate that friendship tie reciprocity increased levels of friendship tie choice, resulting in youth choosing more friends. Reciprocity is likely an important dimension characterizing close, intimate friendships that occur during adolescence. Mutually reciprocated relationships are also thought to be important for short and long term social and emotional functioning (Buhrmester and Furman 1986) and adjustment and competence among adolescents (Buhrmester 1990).

The observed positive effect of transitive triplets along with the negative effect of three-cycles on friendship tie choice suggests evidence of local hierarchy in the network structure. Such hierarchy indicates that some youth were more prestigious or popular than others. Popularity in adolescence has been positively associated with salutary outcomes including higher levels of ego development, secure attachment, and increased adaptive interactions with mothers and best friends (Allen et al. 2005). However, popularity may also have deleterious consequences for development, as popular adolescents appear vulnerable to being socialized into delinquent behavior which can be normative in their peer groups (Allen et al. 2005). Our findings also indicated that smokers were more likely than non-smokers to be nominated as friends, likely indicating the general popularity of smokers among the youth in our sample. Popular individuals are thought to set normative trends in their environments (Kelly et al. 1991); thus, it is likely that smoking was normative in this population. In addition, youth were likely to form ties with other popular youth, with a preferential attachment mechanism for less popular adolescents to be connected to more popular adolescents. Our finding that smokers were more popular than non-smokers is consistent with some past studies finding a positive relationships between popularity and adolescent smoking (Alexander et al. 2001; Valente et al. 2005), however, runs counter to the general pattern observed in past studies of adolescent social networks and smoking behavior including (Ennett and Bauman 1993; Ennett et al. 2006) indicating that smokers are more socially isolated than non-smokers. Overall, our findings suggest a hierarchical social milieu, in which popular youth smoke.

Consistent with literature indicating that adolescent friendship pairs demonstrate similarity on multiple dimensions (Kandel 1978a), our findings also indicate homophily effects in predicting friendship tie choice. Various theoretical perspectives support the contention that similarity is a key driver of adolescent friendships, including Balance Theory (Heider 1958) and Social Exchange theory (Homans 1974), positing that similarity generates attraction. Our findings indicated that adolescents were likely to choose friendships based on similarity in smoking status, which is consistent with past studies of youth friendship network and smoking behavior (DeLay et al. 2013; Mathys et al. 2013). Youth also were likely to choose friends in their own grade, which is consistent with past research (Kandel 1978b), and choose friends whose parents had a similar education level to their own parents (Hamm 2000; Savin-Williams and Berndt 1990). Perhaps friendship choice among adolescent youth is based on multiple dimensions of similarity, and is a basis from which a relationship develops.

Our findings also indicate the relevance of key parental influences for friendship tie choice behavior. Adolescents with higher levels of parental support formed more friendship ties over time. This finding is consistent with research indicating that parents can influence the structure of youths’ friendship networks by regulating friends to whom youth are exposed (Falbo et al. 2001). In addition, our finding is consistent with other research indicating that perceived parental support positively relates to social competence in early adolescence, which likely plays a key role friendship tie choice (Rubin et al. 2004). Hence, parental support may at once regulate youths’ friendship tie choices and facilitate stronger social competencies in adolescents, both of which then affect friendship tie choice behavior.

Secondly, our findings indicated that having a parental home smoking environment conducive to smoking lead to fewer friendship ties over time independent of peer effects, in the small school sample. It is possible that having a parent who smokes and having cigarettes accessible in the household may have somehow limited youth in making new friendships, perhaps due to factors specific to home environments in which parents smoke. It is also possible that parental monitoring from youths’ friends’ families may have inhibited friendships from forming with youth whose parents smoke and have cigarettes available in the household. This effect was only detected in the small school sample, possibly due to the higher level of parental monitoring in this sample.

While we hypothesized that the three parental influences under study would affect the choice of friendship ties with smokers in predicting friendship tie choice, we only observed an interaction between parental monitoring and choosing friends that smoke, and only in the large school sample. Our findings indicate that those with more parental monitoring chose fewer smokers, mirroring past literature suggesting that parental monitoring deters affiliation with substance using adolescents, and suppositions from Social Control Theory indicating that parental constraints deter adolescent delinquency (Hirschi 1969; Nye 1958). This finding is also consistent with studies demonstrating that parental monitoring indirectly affects smoking by inhibiting affiliation with friends who smoke (Simons-Morton et al. 2004), and with other research indicating that the relationship between using cigarettes with friends and adolescents’ own smoking was strongest under conditions of low parental monitoring (Kiesner et al. 2010). Perhaps this interaction effect was only observed in the large school sample because the distribution of smoking in the large school sample is skewed towards heavier smokers and thus youth had more opportunities to make friends with smokers. Moreover, examining the interactions under study within the context of dynamic adolescent networks moves beyond existing work such as Knoester et al. (2006) and (Engels et al. 2004), by considering the direct and multiplicative effects of three parental influences in the context of dynamically modeled adolescent friendship networks which account for key network characteristics and processes in shaping the coevolution of friendship tie choice and smoking behavior. Lastly, that we found some evidence of an interaction between the peer and parental influences also provides some support for the ecological contention that these influences interact in affecting development.

While the other interaction parameters with parental support and the parental home smoking environment were in the expected direction—suggesting that parental support and a low home smoking environment might lead to fewer ties with smokers—they were not statistically significant. In this study it appeared that parental monitoring was the most important parental factor minimizing the possibility of creating friendships with smokers, especially in the larger school. In all, our findings indicate evidence that these parental effects were important to friendship tie choice net of the network effects, through both direct and moderated pathways.

Adolescent Smoking

Turning to factors predicting smoking behavior, the findings indicate that peer influence increased smoking behavior, as youth adjusted their own smoking behavior over time to become more similar to the average of their friends’ smoking behavior. This finding is consistent with numerous past studies noting the positive relationship between peer influence and adolescent smoking (Maxwell 2002; Urberg 1992), and interpreting more broadly, other research indicating that peer influence is a key process shaping adolescent development (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011; Dishion and Tipscord 2011).

Turning to the other network effects, the relationship between in-degree (popularity) and adolescent smoking was not significant, indicating that youth who were popular were not more likely to increase their smoking behavior over time. Thus, whereas smokers were more likely to be chosen as friends, such popular individuals did not smoke more over time, suggesting a one directional relationship. Given the longstanding debate regarding whether popular or unpopular youth are more likely to smoke, our differential findings for whether smokers are more popular, or whether popular students smoke more over time, highlight the importance of testing these processes with dynamic models.

In addition to the network effects under study, some of the parental influences impacted smoking behavior. Parental monitoring was protective for smoking in the small school sample, but not in the large school sample, perhaps because the former had a higher level of parental monitoring. The negative effect of parental monitoring on smoking behavior indicated that youth with more parental monitoring smoked less over time. This finding is consistent with past studies indicating a negative relationship between parental monitoring and adolescent smoking (Li et al. 2000) and other research indicating that inadequate parental monitoring predicted tobacco use at a later time among adolescents (Biglan et al. 1995). In general, studies suggest that parental monitoring appears to decrease adolescent smoking, and our findings indicate that this effect persists over time.

Our findings also indicated that a home parental context conducive to smoking increased adolescent smoking in both samples. This finding corroborates previous studies indicating parental smoking increases adolescent smoking (Chuang et al. 2005; Engels et al. 2004). The parental home smoking context may affect adolescent smoking via various mechanisms, including parental modeling of smoking behavior, the availability of cigarettes in the home may serve as a temptation to smoke, and youth likely adopt their parents’ norms around smoking. Each of these possibilities may lead to youth being open to affiliating with friends who smoke over time or to deciding to smoke on their own.

Regarding the interactions between the parental influences and peer influence, we found no evidence that the relationships between parental influences and smoking were moderated by the effect of peer influence. The statistical interactions were not only insignificant across both samples, but often in the direction opposite of expectations. It appears that these parental influences and peer processes acted independently in their effect on adolescent smoking in our study sample. Thus, although the home smoking environment is associated with increases in smoking over time, it does not operate synergistically with friends’ smoking behavior.

Limitations

This study has limitations to note. The name generator item utilized in this study was limited to naming up to 5 female and 5 male friends. It is unclear how our findings would have differed had the adolescents sampled been allowed to nominate all of their friends. Our self-reported smoking measure is likely subject to self-report biases including social desirability and recall biases. Also, we did not have a biological measure of smoking, to validate adolescents’ self-reports of smoking. Because the Add Health study only follows these adolescents for three time points over a 1.5 year period, we are only able to observe the co-evolution of the network and adolescent smoking over this short period of time. A longer time period would provide more evidence regarding the evolution of these processes.

Implications for Prevention

Our findings have implications for future research. First, future studies should more closely examine possible interactions between the peer and parental influences under study in shaping friendship tie choice behavior and smoking. Specifically, future research should examine the role of parental monitoring for friendship tie choice behavior in general, and for choosing friends who smoke in particular. Future studies warrant a closer examination of parental support and its dimensions to understand which domains of support promote adolescent friendship tie choice behavior. Our findings also suggest merit in a careful examination of the specific mechanisms through which a parental home context conducive to smoking affects friendship tie choice, and whether these factors also relate to adolescent smoking. Regarding the network effects, our findings suggest gaining a better understanding of the key role of reciprocated relationships, local hierarchy in adolescent networks, popularity, as well as homophily on smoking status, grade, and parental education, in shaping friendship tie choice.

Our findings also have some practical implications, suggesting the merit of peer based interventions, targeting the hierarchical structure of youths’ friendship networks, to reset norms at school regarding smoking beginning with popular youth, who likely hold positions high in the social hierarchy. Given that we find that peer influence increases adolescent smoking, popular youth who do not smoke or are considering quitting may be targeted to influence other youth to not smoke. Such youth could be identified as seeds to diffuse anti-smoking norms and peer influences which would then diffuse downward throughout the social hierarchy, to less popular youth. Interventions could be tailored to youth within grade, given our findings of homophily on grade in friendship tie choice. The findings also suggest merit in targeting both the school based friendship network simultaneously with youths’ parents, in an ecological intervention approach, to target adolescents’ home environments and friendship networks, simultaneously. Such interventions could include the aforementioned strategies targeting popular youth coupled with empathy training for parents to learn how to better provide support to and strategies to improve parental monitoring of their adolescent children, and strategies to decrease youths’ access to cigarettes in the home, if parents are smokers and cigarettes are accessible.

Conclusion