Abstract

Sterol esters are currently gaining importance because of their recent recognition and application in the food and nutraceutical industries. Phytosterol esters have an advantage over phytosterols, naturally occurring antioxidants, with better fat solubility and compatibility. Antioxidants and hypocholesterolemic agents are known to reduce hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis. The objective of the study was to determine the effects of different sterol esters on cardiac and aortic lipid profile and oxidative stress parameters and on the development of atherosclerosis in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. Thirty six rats were divided into six groups: control group, hypercholesterolemic group and four experimental groups fed with EPA-DHA rich sitosterol ester in two different doses, 0.25 g/kg body wt/day and 0.5 g/kg body wt/day, and ALA rich sitosterol ester in two different doses, 0.25 g/kg body wt/day and 0.5 g/kg body wt/day. The sterol esters were gavaged to the rats once daily for 32 days. The cardiac and aortic total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol and triglyceride level which were elevated in hypercholesterolemia were significantly lowered by both the doses of sterol esters. Antioxidant enzyme activities were significantly decreased and peroxidation product, malondialdehyde was increased in hypercholesterolemia. But administration of both the sterol esters was able to increase enzyme activities and decrease MDA level in the tissues. Histological study of cardiac tissues showed fatty changes in hypercholesterolemic group which was reduced by treatment with sterol esters. The higher doses of sterol-ester caused better effects against hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Phytosterol ester, Hypercholesterolemia, Antioxidant enzymes, Lipid peroxidation

Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease (Prasad et al. 1994; Steinberg 1992). It increases the levels of lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA) in blood and aortic tissues (Yamamoto et al. 2002). These suggest that during hypercholesterolemia there must be an increase in the levels of oxygen–free radicals (OFRs) which could be due to increased production and/or decreased destruction of the same in aortic tissues. In fact, OFR-producing activity of polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes (PMNL-CL) is increased in hypercholesterolemia (Yamamoto et al. 2002). Various factors such as lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress etc. has been implicated in the release of OFRs from PMN leukocytes during hypercholesterolemia (Yamamoto et al. 2002). OFRs exert their cytotoxic effects by causing peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids of membrane phospholipids, which can result in an elevation in membrane fluidity and permeability and loss of cellular integrity (Cheon and Cho 2014). Oxidative stress is also known to alter antioxidant enzymes viz. superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, reduced glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) (Hunter 1990; Prasad et al. 1997a; Sengupta and Ghosh 2010).

A high plasma cholesterol level and the occurrence of coronary heart disease are strongly interrelated. Dietary supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) is associated with a reduction in the incidence of occlusive vascular diseases including both atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Administration of oils rich in n-3 PUFA decreases plasma cholesterol and triglyceride content in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic human subjects and in rats. Feeding of such oils was found to reduce aggregability of platelets, thus lowering the chance of thrombosis, a major factor in heart attacks and strokes (Sengupta and Ghosh 2010). Although both the control and treatment groups exhibited severe and comparable degrees of hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia, the incidence of disease was lower in the latter group; for example, the rate of luminal encroachment and the lesion area of the right coronary artery were only 24 % and 25 %, respectively, of those in the control group. Such a dramatic inhibition of atherosclerosis in the absence of any significant differences in the total or low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol levels could be attributed to the decreased formation of arachidonic acid (ARA)-derived prostaglandins through cyclo-oxygenase activity. n-3 PUFA are generally considered as the main causative factor of the aforesaid hypolipidemic effect, but data are insufficient regarding the effect of n-3 PUFA in combination with phytosterol against hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

A phytosterol is a naturally occurring sterol compound (e.g. sitosterol, campesterol, Brassicasterol and stigmasterol) derived from plant that resembles mammalian cholesterol and steroid hormones. Typically obtained from vegetable oils, nuts, soy, corn, woods and beans, phytosterols compete with dietary cholesterol for absorption in the intestines, resulting in lower blood cholesterol concentrations, specifically total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C (Gylling and Meittinen 1999; Hallikainen et al. 2000; Jones 1999; Lottenberg et al. 2003; Newby et al. 2006; Plat and Mensink 2000). The effectiveness of phytosterols and phytostanols are endorsed by the United States National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III at 2 g/day as an essential feature of therapeutic lifestyle changes along with diet modifications, weight reduction, intake of viscous fibers and increased physical activity to reduce risk for CHD. As a part of therapeutic lifestyle program, supplementing with phytosterols considers to be an effective means of reducing one’s cholesterol. Indicative of the clinical evidence supporting phytosterols, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the health claim for plant sterols and stanols recognizing that plant sterols may reduce the risk of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

Phytosterols have poor water solubility and bioavailability. Esterification of phytosterols with different oils increases the availability and acceptability of phytosterols. The individual anti-atherogenic effect of phytosterol, fish oil and flaxseed oil are enhanced if the oils are esterified with phytosterols. The aim of our present investigation was to examine the effects of ingesting phytosterol esters on indices of cholesterol metabolism in hypercholesterolemic adults. Further, the effect of the sterol esters in modulating the plasma and tissue lipids will also be examined. The role of the two sterol esters (EPA-DHA rich sterol ester and ALA rich sterol ester) in combating hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis will be compared in the same study.

Materials and methods

Preparation of β-sitosterol esters

A standard β-sitosterol sample was procured from Fluka Chemicals and analyzed at the laboratory by gas chromatography (GC). Fish oil (Mega-Shelcal capsules from Elder Pharmaceuticals, India) was used as the source of eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and the GC analysis of the fish oil showed that the oil contained 32 % EPA and 22 % DHA. Refined, bleached flaxseed oil procured from V.K.V.K. Oil Limited, Kolkata, India, was used as the source of alpha linolenic acid (ALA), and the GC analysis of the oil showed the presence of 54 % ALA in the oil. Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase (Lipozyme TLIM) used as biocatalyst, was a generous gift from Novozyme India, Ltd., Bangalore, India. Phytosterol esters were formed by enzymatic transesterification reactions in a packed bed reactor and their fatty acid compositions were analyzed by GC (Sengupta et al. 2010). The yield of phytosterol esters were 95 % EPA-DHA rich sterol ester and 95.2 % ALA rich sterol ester. The sterol esters were purified using column chromatography.

Fatty acid compositional analysis of phytosterol esters

The percent compositions of various sterol esters according to fatty acid compositions were determined by GC. The GC instrument (Agilent, model 6890 N) used was equipped with a FID detector and capillary HP 5 column (30 m, 0.32 mm I.D, 0.25 μm FT). N2, H2 and airflow rates were maintained at 1, 30 and 300 ml/min, respectively. Inlet and detector temperature was kept at 250 and 275 °C, respectively, and the oven temperature was programmed at 65–230–280 °C with a 1-min hold at 65 °C and an increase rate of 20 °C/min and 1 min hold up to 230 and 8 °C/min with 24 min hold up to 280 °C. Sterol esters were fractionated according to the fatty acid composition from which the amount of each fatty acid incorporated in the ester was calculated. The retention time (Rt) of each sterol ester had been previously standardized in GC by preparing esters of β-sitosterol with different fatty acids.

Animal and treatment

Animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of Animal Ethical Committee of Dept. of Chemical Technology, University of Calcutta. Adult male albino rats of Wistar strain were housed and given stock diet (Table 1) and water ad libidum. The duration of the experimental period was 32 days. The animals were divided into six groups with six rats in each: Group I: vehicle treated control animals, Group II: rats were fed with a high cholesterol diet(rat stock diet supplemented with 1 % cholesterol) for 32 days, Group III: rats received EPA-DHA phytosterol ester (0.25 g/kg body weight/day, oral gavage) for 25 days alongwith a high cholesterol diet for 32 days, Group IV: rats received EPA-DHA phytosterol ester (0.5 g/kg body weight/day, oral gavage) for 25 days along with a high cholesterol diet for 32 days,Group V: rats fed with high cholesterol diet for 32 days and ALA phytosterol ester (0.25 g/kg body weight/day, oral gavage) for the last 25 days, Group VI: rats fed with high cholesterol diet for 32 days and ALA phytosterol ester (0.5 g/kg body weight/day, oral gavage) for the last 25 days. Groundnut oil was used as the vehicle and given to all the groups. At the end of the experiment the feeding of rats was stopped and after 12 h fasting, the rats were anesthetized by chloroform. The heart and aorta were removed, rinsed with ice-cold saline, blotted, weighed and stored at −20 °C until analyzed.

Table 1.

Stock Diet Composition

| Stock Diet | Amount (g/100 g food) |

|---|---|

| Starch | 55 |

| Fat free casein | 18 |

| Mineral Mixture | 4 |

| Husk | 3 |

| Groundnut oil | 20 |

Cardiac and aortic lipid profile

After 32 days of dietary treatment, rats were fasted for 12 h. Then they were anesthetized with chloroform and sacrificed. Heart and aorta were harvested, weighed and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Tissue (cardiac and aortic) lipids were extracted by the method of Folch et al. (Folch et al. 1951). One gram of tissue was homogenized with 1 ml of 0.74 % potassium chloride and 2 ml of different proportions of chloroform and methanol for 2 min and then centrifuged. The mixture was left overnight and the chloroform layer was filtered through a Whatman filter paper (no.1). The chloroform layer was dried, the tissue lipid contents were measured and the lipid was used for lipid analysis. The cardiac and aortic lipids were used for the estimation of total cholesterol, triglyceride and phospholipid estimation by using standard kits.

Histological study

Permanent preparations were made using routine methods (Edem 2009). The cardiac tissues were fixed in 10 % buffered formalin. The tissues were subsequently dehydrated in upgraded concentrations of alcohol, cleansed in xylene, impregnated and embedded in paraffin wax. Several sections of 3–6 μm were cut using a microtome. The sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Preparation of cardiac and aortic tissue homogenate and supernatant

Aorta (between the origin and bifurcation of iliac arteries) and heart were removed, cleaned of gross adventitial tissue and divided longitudinally into two halves. One half was used for estimation of atherosclerotic plaques and histology. The other half was used to prepare homogenate for antioxidant estimation.

Antioxidant enzymes estimation

Measured amounts of cardiac and aortic tissues were taken and homogenized in different concentrations of phosphate buffer. The samples were then centrifuged and the supernatants were used for enzyme assay. The activity of CAT was determined spectrometrically by the method of Aebi (1984). SOD activity was assayed by measuring the auto oxidation of haematoxylin as described by Martin et al. (1987). GSH was determined by the method of Ellman (1959). Total activity of GPx (GPx EC.1.11.1.9.) was determined in the tissue homogenates and plasma according to Flohe and Gunzler (1984). All the enzyme activities were expressed in terms of enzyme units per mg protein. Protein was determined using the standard method of Lowry et al. (Lowry et al. 1951).

Measurement of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation level in the homogenate were measured as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances as a well known method. Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances were extracted in a mixture of butanol and pyridine, which was separated by centrifugation. The fluorescence intensity of the butanol/pyridine solution was measured at 553 nm with excitation at 513 nm. Lipid peoxidation in the cardiac and aortic tissues were expressed as nmol MDA/mg protein (Niehaus and Samuelsson 1968).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Repeated measures ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of different parameters.

Results

Fatty acid composition of phytosterol esters

The transesterification reaction was carried out in the packed bed reactor. In the first set of reaction fish oil was used as a source of EPA & DHA fatty acids and in the second set, flaxseed oil was used as a source of ALA fatty acid. Approximately 32 % EPA & 22 % DHA was present in fish oil and 54 % of ALA in flaxseed oil. Analysis of fatty acid composition of sterol-esters by GC showed that almost all the fatty acids present in the different oils (in TAG form) were incorporated in the corresponding esters. Table 2 shows the fatty acid profile of the two sitosterol esters produced in packed bed bioreactor.

Table 2.

Fatty Acid Profiles of EPA-DHA rich and ALA rich Sterol Esters used as Nutraceutical

| Fatty acid → | Fatty Acid (% w/w) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample ↓ | C14:0 | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C18:3 | C20:0 | C20:1 | C20:5 | C22:0 | C22:1 | C24:0 | C22:6 |

| Phytosterol-DHA-EPA Ester | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 2.44 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 1.90 ± 0.27 | 3.05 ± 0.34 | 2.75 ± 0.64 | 5.12 ± 0.83 | 39.20 ± 1.10 | 5.65 ± 0.37 | 2.19 ± 0.08 | 3.84 ± 0.19 | 31.98 ± 1.63 |

| Phytosterol-ALA Ester | - | 12.48 ± 0.60 | 1.89 ± 0.17 | 28.28 ± 1.09 | 12.83 ± 1.01 | 44.52 ± 1.76 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Values are expressed as mean ± S.D

Body Weight

The changes in the body weight gain of the male albino rats of the normal and experimental groups are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Body Weight Gain in 32 days in Rats Fed Experimental Diets

| Dietary Groups | Body Weight Gain (g) |

|---|---|

| I | 25.57 ± 1.22a |

| II | 39.90 ± 0.77b |

| III | 24.16 ± 1.07a |

| IV | 22.34 ± 1.11a |

| V | 24.00 ± 1.13a |

| VI | 22.50 ± 1.20a |

I: Control; II: Hypercholesterolemic Control; III: Low dose of EPA-DHA ester; IV: High dose of EPA-DHA ester; V: Low dose of ALA ester; VI: High dose of ALA ester

Values are mean ± S.E.M (n = 6 rats) Values not sharing a common superscript within a column are statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Changes in cardiac and aortic lipid profile

The cardiac and aortic lipid profiles of rats of different groups are shown in Tables 4 and 5. The type of fat consumed altered the different lipid concentration in cardiac and aortic tissues. Rats fed with control groundnut oil had cardiac and aortic total cholesterol of 202.08 mg/g tissue and 198.23 mg/g tissue respectively which was significantly increased to 544.83 mg/g tissue and 499.98 mg/g tissue respectively by feeding them high cholesterol diet. Both the doses of sterol ester brought about a decrease in total cholesterol which was much more in case of EPA-DHA rich sterol ester. The higher doses produced better hypocholesterolemic effect than the lower dose. Similar results were found in case of estimation of triglyceride levels. Thus the sterol esters lowered the levels of triglyceride significantly (p < 0.05). An opposite trend was observed in the case of phospholipid. Phospholipid level decreased in hypercholesterolemic subjects in comparison to the normal both in the case of cardiac tissue and aorta. However administration of sterol esters increased the phospholipid level and the increase was more in the case of higher doses of sterol esters. EPA-DHA rich sterol ester showed better hypolipidemic effect than ALA rich sterol ester.

Table 4.

Cardiac lipid profile

| Parameters (mg/g tissue) | I | II | III | IV | V | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol | 202.08 ± 1.20a | 544.83 ± 3.32b | 344.07 ± 2.30c | 200.27 ± 2.45d | 376.76 ± 1.98e | 254.75 ± 0.40d |

| Triglycerides | 120.98 ± 0.57a | 250.09 ± 4.50b | 190.25 ± 0.59c | 129.56 ± 0.33a | 210.80 ± 1.89d | 141.12 ± 2.90e |

| Phospholipids | 210.90 ± 1.50 | 130.87 ± 2.80a | 168.98 ± 1.67b | 225.43 ± 1.32b | 143.20 ± 1.99b,c | 209.87 ± 0.50b,d |

I: Control; II: Hypercholesterolemic Control; III: Low dose of EPA-DHA ester; IV: High dose of EPA-DHA ester; V: Low dose of ALA ester; VI: High dose of ALA ester

Values are mean ± S.E.M (n = 6 rats) Values not sharing a common superscript within a row are statistically significant (p <0.05)

Table 5.

Aortic lipid profile

| Parameters (mg/g tissue) | I | II | III | IV | V | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol | 198.23 ± 0.99a | 499.98 ± 2.30b | 320.24 ± 1.99c | 202.30 ± 2.30d | 329.88 ± 2.00e | 245.64 ± 0.87d |

| Triglycerides | 120.98 ± 0.57a | 250.09 ± 4.50b | 190.25 ± 0.59c | 129.56 ± 0.33a | 210.80 ± 1.89d | 141.12 ± 2.90e |

| Phospholipids | 175.49 ± 3.20 | 88.64 ± 1.22a | 120.83 ± 2.66b | 190.70 ± 1.09b | 115.54 ± 1.99b,c | 170.55 ± 1.77b,d |

I: Control; II: Hypercholesterolemic Control; III: Low dose of EPA-DHA ester; IV: High dose of EPA-DHA ester; V: Low dose of ALA ester; VI: High dose of ALA ester

Values are mean ± S.E.M (n = 6 rats) Values not sharing a common superscript within a row are statistically significant (p <0.05) c

Histopathological changes in the heart

Microscopic examination of the cardiac cells of the six groups was performed and the histopathological slides are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1a highlighted the cardiac histology of the control rats. Figure 1b highlighted the abnormal fatty change in the heart due to hypercholesterolemia. Figure 1c and d highlighted the treatment of the heart with EPA-DHA rich sterol ester. The fatty change was fully cured in case of the treatment with higher dose of EPA-DHA rich sterol ester. Figure 1e and f highlighted the treatment of the heart with ALA rich sterol ester. Here again the effect of the higher dose was much better. The effect of treatment of the rats with EPA-DHA rich sterol ester was greater in comparison with ALA rich sterol ester.

Fig. 1.

Pictomicrographs of cardiac tissues a Control; b Hypercholesterolemic Control; c Low dose of EPA-DHA ester; d High dose of EPA-DHA ester; e Low dose of ALA ester; f High dose of ALA ester (200× magnification, scale bar = 100 μm for all the pictomicrographs) (↔-10 μm)

Changes in Antioxidant Enzymes

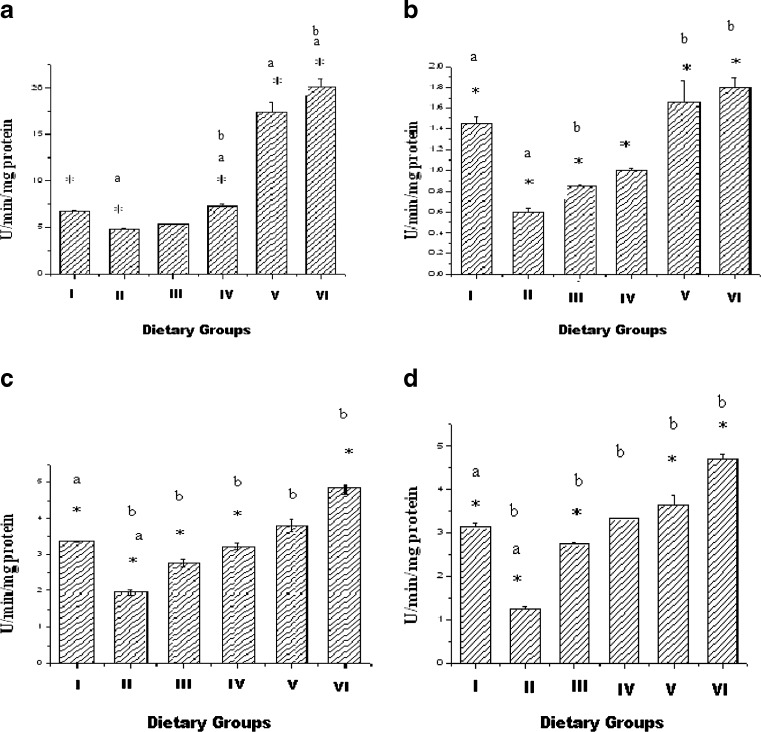

Changes in the cardiac tissue

The changes in the GSH activity in the six groups are summarized in Fig. 2a. The activity of Group II was decreased in comparison with Group I. The activity of the enzyme was enhanced when the rats were treated with the sterol esters. There was no significant change when the rats were fed with the lower dose of EPA-DHA ester ester (Group III), but significant change took place in the rats treated with the higher dose of EPA-DHA ester (Group IV). The result was not so in case of ALA ester. There was increase in the activity of GSH in both the doses, but the activity increased to a higher level in case of the second dose (Group VI).

Fig. 2.

Activity of antioxidant enzymes (a-GSH, b-GPx, c-SOD, d-CAT) in cardiac homogenate. Values are Mean ± S.E.M. of 6 rats. I-Control, II- Hypercholesterolemic (HCD), III- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(25 mg/day), IV- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(50 mg/day), V- HCD + ALA Ester(25 mg/day), VI- HCD + ALA Ester(50 mg/day) *p <0.05, Group I vs Groups II, III, V, VI; a p <0.05, Group I vs Group II, b p <0.05 Group II vs Groups III, IV,V, VI

The changes in the activity of GPx in all the six groups are depicted in Fig. 2b. The results showed that hypercholesterolemia decreased the activity of the enzyme and sterol esters prevented the decrease in the GPx activity induced by hypercholesterolemia. The treatment with both the doses of both the sterol esters increased the activity of the enzyme significantly. But the effect of the higher doses in the case of both the sterol esters was much better. ALA rich sterol ester produced much better result than the EPA-DHA rich sterol ester.

Changes in SOD activity of the six groups are shown in Fig. 2c. SOD activity was reduced significantly by hypercholesterolemia. The activity was increased in Groups III, IV, V and VI. The activity of SOD in Group III and Group IV was lower than the activity in Groups V and VI.

Changes in catalase activity of the six groups are shown in Fig. 2d. Catalase activity was also reduced by hypercholesterolemia. The activity was increased in Group III, IV, V and VI. The activity of CAT in Group III and Group IV was lower than the activity in Groups V & VI.

Changes in the aorta

The changes in the GSH activity in the six groups are summarized in Fig. 3a. The activity of Group II was decreased in comparison with Group I. The activity of the enzyme was enhanced when the rats were treated with the sterol esters. The effect of ALA rich sterol ester as a whole was much better than EPA-DHA rich sterol ester.

Fig. 3.

Activity of antioxidant enzymes (a-GSH, b-CAT, c-GPx, d-SOD) in aorta homogenate. Values are Mean ± S.D of 6 rats. I-Control, II- Hypercholesterolemic (HCD), III- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(25 mg/day), IV- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(50 mg/day), V- HCD + ALA Ester(25 mg/day), VI- HCD + ALA Ester(50 mg/day) a p <0.05, Group I vs Group II; b p <0.05, Group II vs Group IV, V, VI; c p <0.05 Group IV vs Group VI

Changes in catalase activity of the six groups are shown in Fig. 3b. Catalase activity was reduced by hypercholesterolemia. The activity was increased in Group III, IV, V and VI. The activity of CAT in Group III and Group IV was lower than the activity in Groups V & VI.

The changes in the activity of GPx in all the six groups are depicted in Fig. 3c. The results showed that hypercholesterolemia decreased the activity of the enzyme and phytosterol esters prevented the decrease in the GPx activity induced by hypercholesterolemia. The treatment with both the doses of ALA rich sterol ester increased the activity of the enzyme significantly. On the other hand the lower dose of EPA-DHA rich sterol ester produced no significant effect, but the higher dose produced significant effect on the activity of the enzyme. ALA rich sterol ester produced much better result than the EPA-DHA rich sterol ester.

Changes in SOD activity of the six groups are shown in Fig. 3d. SOD activity was reduced significantly by hypercholesterolemia. The activity was increased in Groups IV, V and VI. The activity of SOD in Group IV was lower than the activity in Group VI.

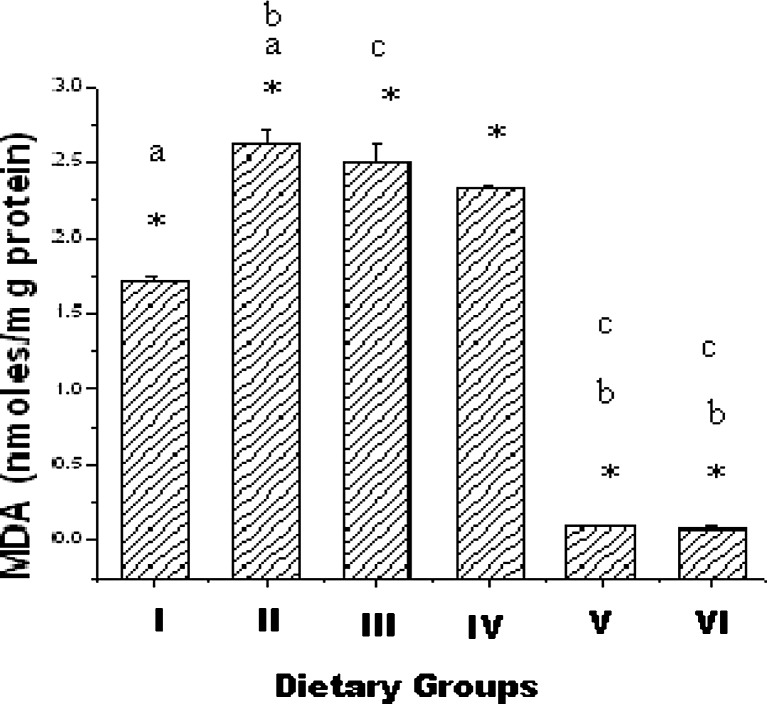

Changes in cardiac tissue MDA

MDA contents of cardiac tissue in the six groups are summarized in Fig. 4. MDA content was 1.72nmoles/mg protein in normal control group. The content increased significantly due to hypercholesterolemia, but administration of ALA rich sterol ester (Groups V & VI) caused significant decrease in the MDA content. There was no significant change in the MDA content when the rats were treated with EPA-DHA rich sterol ester (Groups III & VI).

Fig. 4.

Cardiac tissue MDA in six groups. Values are Mean ± S.E.M. of 6 rats. I-Control, II- Hypercholesterolemic (HCD), III- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(25 mg/day), IV- HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(50 mg/day), V- HCD + ALA Ester(25 mg/day), VI- HCD + ALA Ester(50 mg/day) *p <0.05, Group I vs Groups II, III, IV, V, VI; a p <0.05, Group I vs Groups II, b p <0.05 Group II vs Groups V, VI, c p <0.05 Group III vs Groups V, VI

Changes in Aortic Tissue MDA

The MDA content of aortic tissue from the 6 groups is summarized in Fig. 5. The level of MDA was higher in Group II, and lower in Groups V and VI. There was no significant change in the MDA levels in Group III and IV.

Fig. 5.

Aortic tissue MDA in six groups. Results are expressed as Mean ± S.E.M C-Control,H-Hypercholesterolemic(HCD),Ia-HCD + EPA-DHA Ester(25 mg/day),Ib-HCD + EPA-DHAEster(50 mg/day),IIa-HCD + ALA Ester(25 mg/day), IIb- HCD + ALA Ester(50 mg/day) a p <0.05, Group C vs Group H; b p <0.05, Group C vs Groups V, VI; c p <0.05, Group V vs Group VI

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to investigate the role of EPA-DHA rich sterol ester and ALA rich sterol ester in preventing hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis. The results show that EPA-DHA rich sterol ester in the dose of 50 mg/day/rat was more effective in lowering plasma lipid parameters than ALA rich sterol ester. This was because of the combined effect of fish oil and phytosterol. EPA-DHA has been shown to be more beneficial in hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis than ALA. Consumption of fish oils enriched in EPA, DHA can markedly decrease the circulating levels of plasma triglycerides and associated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Prasad et al. 1997b). Phytosterols are effective in reducing the absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol from the intestinal tract, by displacing cholesterol and decreasing the hydrolysis of cholesterol esters in the small intestine (Chang et al. 1999).

Cardiac tissue MDA content increased in the hearts of high cholesterol-fed rats (Group II) and decreased significantly in treated groups (Groups V & VI). There was no significant change in the MDA content in the hearts of EPA-DHA rich sterol ester treated groups (Group III & IV). The increase in MDA level in Group II suggests oxidative damage. EPA-DHA rich sterol ester treated groups produced no significant change because n-3 PUFA present in fish oil are susceptible to oxidative damage. n-3 PUFA are known to elevate the peroxisomal β-oxidation (Chen et al. 1993). The crucial enzyme of β-oxidation, fatty acyl CoA oxidase produces hydrogen peroxide increasing oxidative stress.

Endogeneous antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, CAT, GPx, as well as antioxidant nutrients, can help to protect cells against free radical damage. Since antioxidant enzymes play an important role in controlling lipid peroxidation (Devi et al. 2000), an increase in the activities of these enzymes could delay the progression of hypercholesterolemia. In the present study there was a decrease in the activity of the four antioxidant enzymes namely SOD, Catalase, GSH and GPx of the heart and aorta of hypercholesterolemic rats. But administration of sterol esters caused an increase in the activity of the enzymes. The effect of ALA rich sterol ester was much better than EPA-DHA rich sterol ester.

The aortic MDA increased in rats fed the high-cholesterol diet but was decreased with ALA rich sterol ester treatment. There was no significant change in the MDA levels in the rats treated with EPA-DHA rich sterol ester. Literature reported increase in aortic MDA in hypercholesterolemic rats; Prasad et al. 1993, 1994).

The severity of the atheromatous lesions in aorta was associated with hypercholesterolemia. There were investigators who had similar results (Castro et al. 2009). Hypercholesterolemic diet produced intimal wall thickening that contained foam cells similar to those observed by others (Castro et al. 2009). EPA-DHA rich sterol ester and ALA rich sterol ester reduced the extent of development of atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic rats. EPA-DHA rich sterol ester also produced a protective effect due to EPA-DHA present in fish oil and phytosterol. This observation is in line with other several studies conducted by different investigators (Ewart et al. 2002; Russell et al. 2002; Demonty et al. 2005, 2006; Jones et al. 2007). Fish oil decreases the level of triglyceride and non-HDL-C in the plasma while phytosterol brings about a reduction in total cholesterol levels. In combination, EPA-DHA rich sterol ester helps in reduction of atherosclerosis.

Hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis was associated with an increase in aortic tissue MDA and a decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity (Prasad and Kalra 1993). Increased aortic tissue MDA suggests an increase in the levels of OFRs, which may be due to decreased antioxidant enzyme activities and other factors. Increased level of OFRs may be due to increased production of PMNLs (Prasad and Kalra 1993), endothelial cells and other blood-borne or vessel wall cells and during prostraglandin and leukotriene synthesis. A decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity may also lead to increased levels of OFRs, which are known to produce endothelial cell injury which can lead to the development of atherosclerosis. PUFA present both in flaxseed oil and fish oil can have quite specific effect on gene expression by regulating the activity or abundance of transcription factors. Our observation that EPA-DHA rich fish oil and ALA rich flaxseed oil results in an induction of antioxidant enzyme expression may, therefore be mediated through an effect on transcription factors: peroxisome proliferator activator receptors (PPARs), liver X receptor (LXRs), hepatic nuclear factor-4 (HNF-4), and sterol element binding proteins (SREBPs) (Clarke 2001). Among these transcription factors, PPARs act as general lipid sensors for a broad spectrum of ligand-dependent transcriptional regulation. Clinical and experimental evidence suggest that PPAR activation decreases the incidence of cardiovascular disease not only by correcting metabolic disorders, but also through direct actions at the level of the vascular wall (Duval et al. 2002). Modulation of PPARs in the cardiovascular system may have a large therapeutic potential. The presence of a PPAR-response element (PPRE) in the 5′-flanking of Cu/Zn SOD1, the key enzyme in the metabolism of OFRs, renders it sensitive to PPAR activation (Yoo et al. 1999).

The results of the present study show that there is an increase in the oxidative stress in the myocardium in hypercholesterolemia. The oxidative stress is associated with a decrease in antioxidant enzyme activities. Sterol esters produced a preventive action on the hypercholesterolemic-oxidative stress in the myocardium due to the combined effects of flaxseed oil, fish oil and phytosterols. ALA rich sterol ester produced a better effect than EPA-DHA rich sterol ester. This is because n-3 PUFAs such as EPA and DHA present in fish oil are highly unsaturated and exhibit hypersensitivity to lipid peroxidation (Nenseter and Drevon 1996). This might be expected to lead to increased plasma atherogenic particles, which could counteract the beneficial effects of such fatty acids on cardiovascular disease. n-3 PUFA leads to the generation of OFRs. However, metabolism of these OFRs was presumably controlled to some extent by the induction of antioxidant enzymes activities. Dismutation of O2− by SOD produces the more stable species H2O2, which in turn is converted to water by CAT and GPx. In this study, the relatively lower levels of O2− and OFR in cardiac tissue after EPA-DHA rich phytosterol ester treatment correlated with, and might be due to the higher activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx in the EPA-DHA rich sterol ester groups. The balance between oxidative stress and antioxidant status of the cell can thus minimize the oxidative perturbations caused by fish oil challenge. Another important finding of the study was that the effect of the higher doses was much better in both the cases.

In conclusion, these results suggest that hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis is associated with an increase in oxidative stress in aorta and phytosterol esters are effective in reducing hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis by reducing oxidative stress and lowering serum levels of cholesterol and non-HDL-C and raising plasma levels of HDL-C. The effect of ALA rich sterol ester in preventing hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis and lowering coronary heart disease was relatively more in comparison with EPA-DHA rich sterol ester.

Acknowledgements

Financial support of University Grants Commission is gratefully acknowledged by authors.

References

- Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Meth Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro SD, Angelantonio ED, Celotto A, Fiorelli M, Passaseo I, Papetti F, Caselli S, Marcantonio A, Cohen A, Pandian N. Short-term evolution (9 months) of aortic atheroma in patients with or without embolic events: a follow-up transoesophageal echocardiographic study. Eur J Echocardio. 2009;10:96–102. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AN, Chang CP, Chou YC, Huang KY, Hu HH. Differential disturbance of apolipoprotein E in young and aged spontaneously hypertensive and stroke-prone rats. J Hypertens. 1999;17:793–800. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Boissonnneault G, Hayek MG, Chow CK. Dietary fat effects on hepatic lipid peroxidation and enzymes of H2O2 metabolism and NADPH generation. Lipids. 1993;28:657–662. doi: 10.1007/BF02536062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon HG, Cho YS. Protection of palmitic acid-mediated lipotoxicity by arachidonic acid via channeling of palmitic acid into triglycerides in C2C12. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:13. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-21-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SD. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene transcription: a molecular mechanism to improve the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2001;31:1129–1132. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonty I, Ebine N, Jia X, Jones PJ. Fish oil fatty acid esters of phytosterols alter plasma lipid but not red cell fragility in hamsters. Lipids. 2005;40:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1432-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonty I, Chan YM, Pelled D, Jones PJH. Fish-oil esters of plant sterols improve the lipid profile of dyslipidemic subjects more than do fish-oil or sunflower oil esters of plant sterols. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1534–1542. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi GS, Prasad MH, Saraswathi I, Raghu D, Rao DN, Reddy PP. Free radicals antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in different types of leukemias. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;293:53–62. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval C, Chinetti G, Trottein F, Fruchart JC, Staels B. The role of PPARs in atherosclerosis. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:422–430. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edem DO. Haematological and histological alterations induced in rats by palm oil-containing diets. Eur J Scien Res. 2009;32(3):405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart HS, Cole LK, Kralovec J, Layton H, Curtis JM, Wright JL, Murphy MG. Fish oil containing phytosterol esters alters blood lipid profiles and left ventricle generation of thromboxane A2 in adult Guinea pigs. J Nutr. 2002;132:1149–1152. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohe L, Gunzler WA. Assay of glutathione peroxidase. Meth Enzymol. 1984;105:114–121. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Ascoli I, Lees M, Meath JA, LeBaron N. Preparation of lipid extracts from brain tissue. J Biol Chem. 1951;191:833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gylling H, Meittinen TA. Cholesterol reduction by different plant stanol mixtures and with variable fat intake. Metabolism. 1999;48:575–80. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(99)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallikainen MA, Sarkkinen ES, Gylling H, Erkkila AT, Uusitupa MI. Comparison of the effects of plant sterol esters and plant stanol ester-enriched margarines in lowering serum cholesterol concentrations in hypercholesterolemic subjects on a low-fat diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:715–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JE. n-3 fatty acids from vegetable oils. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:809–814. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.5.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ. Cholesterol lowering action of plant sterols. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 1999;1:230–5. doi: 10.1007/s11883-999-0037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ, Demonty I, Chan YM, Herzog Y, Pelled D. Fish-oil esters of plant sterols differ from vegetable-oil esters in triglyceride lowering, carotenoids bioavailability and impact on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PA-1) concentrations in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Lipids Health Dis. 2007;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottenberg AM, Nunes VS, Nakandakare ER, Neves M, Bernik M, Lagrost L, dos Santos JE, Quintão E. The human cholesteryl ester transfer protein 1405 V polymorphism is associated with plasma cholesterol concentration and its reduction by dietary phytosterol esters. J Nutr. 2003;133:1800–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Roesborough MJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with Folin-Phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JP, Dailey M, Sugarman E. Negetive and positive assays of superoxide dismutase based on haematoxylin autoxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;255:329–36. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenseter MS, Drevon CA. Dietary polyunsaturates and peroxidation of low density lipoprotein. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1996;7:8–13. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199602000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby LK, LaPointe NM, Chen AY, Kramer JM, Hammill BG, DeLong ER, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM. Long term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2006;113:203–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.505636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus WG, Samuelsson B. Formation of malonaldehyde from phospholipid arachidonate during microsomal lipid peroxidation. Eur J Biochem. 1968;6:126. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plat J, Mensink RP. Vegetable oil based versus wood based stanol ester mixtures: effects on serum lipids and haemostatic factors in non-hypercholesterolemic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:101–12. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K, Kalra J. Oxygen free radicals and hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis: effect of Vitamin E. Am Heart J. 1993;125:958–973. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90102-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K, Kalra J, Lee P. Oxygen free radicals and hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis: effect of prubucol. Int J Angiol. 1994;3:100–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02014924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K, Mantha SV, Kalra J, Kapoor R, Kamalaranjan BRC. Purpurogallin in the retardation of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis. Int J Angiol. 1997;6:157–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01616174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad K, Mantha SV, Muir AD, Westcott ND. Reduction of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis by CDC-flaxseed with very low alpha-linolenic acid. Atherosclerosis. 1997;132:69–76. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)06110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JC, Ewart HS, Kelly SE, Kralovec J, Wright JL, Dolphin PJ. Improvement of vascular dysfunction and blood lipids of insulin-resistant rats by a marine oil-based phytosterol compound. Lipids. 2002;37:147–152. doi: 10.1007/s11745-002-0874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta A, Ghosh M. Modulation of platelet aggregation, haematological and histological parameters by structured lipids on hypercholesterolemic rats. Lipids. 2010;45:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta A, Pal M, SilRoy S, Ghosh M. Comparative study of sterol ester synthesis using Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase in stirred tank and packed bed bioreactors. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2010;87:1019–1025. doi: 10.1007/s11746-010-1587-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D. Antioxidants in the prevention of human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1992;85:2338–2345. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.6.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Sakata N, Meng J, Sakamoto M, Noma A, Maeda I, Okamoto K, Takebayashi S. Possible involvement of increased glycoxidation and lipid peroxidation of elastin in atherogenesis in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:630–636. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HY, Chang MS, Rho HM. Induction of the rat Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene through the peroxisome proliferator-responsive element by arachidonic acid. Gene. 1999;234:87–91. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]