Abstract

The aim of this work was to evaluate the physico-chemical, instrumental color and texture, and sensory qualities of restructured tilapia steaks elaborated with small sized (non-commercial) tilapia fillets and different levels of microbial transglutaminase (MTG). Four concentrations of MTG were used: CON (0 % MTG), T1 (0.1 % MTG), T2 (0.5 % MTG), and T3 (0.8 % MTG). In addition, bacterial content and pH shifts were also evaluated during 90 days of frozen storage. The different levels of MTG did not affect (P > 0.05) either the proximate composition of the restructured tilapia steaks or the bacterial growth during the frozen storage. MTG improved (P < 0.05) cooking yield and instrumental hardness and chewiness as well as sensory (salty taste, succulence and tenderness) attributes; strongly contributing to greater overall acceptance. Therefore, restructured tilapia steaks manufactured with MTG are potentially valued-added products with good consumer acceptance and better purchase-intention than steaks formulated with 0 % MTG.

Keywords: Oreochromis niloticus, Freshwater fish, Restructured steaks, Microbial transglutaminase, Just-about-right scales

Introduction

Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is the most farmed fish in Brazil with a nation-wide distribution. In 2010, approximately 155.450 t of tilapia were produced, representing 39.4 % of the total farmed freshwater fish (MPA 2012). Tilapia fillets are the most valuable products thus, most studies focused on its quality (Cozzo-Siqueira and Oetterer 2003; Monteiro et al. 2012; Soccol et al. 2005), where the standardization of the fillet size is important. However, due to heterogeneity of the growth performance and rearing methods, the production of animals under the desired weight results in irregularity in the lots and rejection by the consumer causing economic loss (Vidotti and Gonçalves 2006). This problem affects 12–14 % of fish farms (Lima 2008).

Restructured meat technology represents an alternative method to increase the profit from irregular fillets. This technology frequently uses several ingredients and additives (polyphosphates, salt, starch, protein isolate and enzymes) to improve the binding strength between the meat pieces and the functional properties of the restructured meat products (Moreno et al. 2008; Ramírez et al. 2006).

Microbial transglutaminase (MTG) is an enzyme that can modify the rheological properties of proteins, improving the desired mechanical properties of meat products (Flanagan et al. 2003; Moreno et al. 2008). Currently, the effect of covalent cross-linking by this enzyme, particularly that from a microbial source, on the rheological properties of food proteins and product development have been studied by many researchers (Gonçalves and Passos 2010; Sanh et al. 2011; Suksomboon and Rawdkuen 2010). The effect of MTG on the gel strength of fish meat varies with the species and the freshness, which is associated with the integrity, denaturation and degradation of myofibrillar proteins (Jiang et al. 2000). Therefore, more studies of the binding efficiency of MTG in products made with fish muscles are necessary, particularly with Nile tilapia, which is widely cultivated worldwide.

In this context, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of different levels of MTG on the instrumental (color and texture), physico-chemical parameters of restructured tilapia steak prepared using sub-optimal sized fillets. Moreover, bacteriological and pH changes were monitored during frozen storage.

Material and methods

Tilapia samples

Six kilograms of tilapia fillets of a sub-optimal size were obtained from a fishery farm in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Immediately after harvesting, the tilapias were eviscerated, washed and filleted. Fillets samples were placed in polyethylene bags, placed on ice (4 °C) and transported to the laboratory. The period from harvest to arrival at the laboratory did not exceed 2 h.

Preparation of the restructured tilapia product

The fillets were randomly divided into four equal groups (CON, T1, T2 and T3). The formulation comprised chilled water, sodium polyphosphate, sodium chloride, garlic powder and onion powder. In addition, MTG (Active WM, Ajinomoto Co. Inc., Kawasaki, Japan) was added in different concentrations according to the formulation: CON (0 %), T1 (0.1 %), T2 (0.5 %) and T3 (0.8 %) (Table 1). Each treatment was manually homogenized during 10 min to allow even distribution of the ingredients, then the batter was tube-casted using poly-vinyl chloride film (PVC) forming 6-cm diameter cylinders. The ends were twisted and sealed and several punctures were made using a syringe needle to release the entrapped air. During the entire processing period, the samples did not exceed 12 °C. The cylinders were stored under refrigeration for cold binding at 4 °C for 24 h. After the binding stage, the PVC film was removed and the cylindrical-shaped samples were sliced into steaks of 1.0 cm thick. Finally, the steaks were individually packed in polyethylene bags, sealed and frozen (−18 °C) until further analysis.

Table 1.

Formulations of restructured tilapia steaks

| Ingredients (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | NaCl | MTG | Sodium tripolyphosphate | Chilled water | Onion powder | Garlic powder |

| CON | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| T1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| T2 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| T3 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

MTG microbial transglutaminase

Proximate analysis

The proximate compositions (moisture, lipid, protein and ash content) were determined according to the AOAC recommendations (AOAC 2000). Four replicates were performed for each treatment and mean value was calculated.

Bacteriological analysis

Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus aureus, total aerobic mesophilic (TAMB) and psychrotrophic bacterial (TAPB) counts, and Salmonella spp. contents were determined as described by APHA (2001). Analyses of the total coliforms, thermotolerant coliforms and Escherichia coli were performed in accordance with Merck’s methodology (Merck 2000). The serial dilutions were prepared according to Conte-Júnior et al. (2010). The described bacterial analyses were performed only on the first day of storage to determine the initial bacterial loads of the raw tilapia fillets and the treatments (CON, T1, T2 and T3). The results were obtained from mean value of three replicates for each treatment.

Frozen storage monitoring

Enterobacteriaceae, TAMB and TAPB counts (APHA 2001) were performed at 0, 15, 30 and 45 days during frozen storage. In addition, the pH value of a homogenized solution of 10 g of muscle sample in 90 mL of distilled water were measured on each of these days using a digital pH meter (Digimed® DM-22) equipped with a DME-R12 electrode (Digimed®) (Conte-Júnior et al. 2008). These analyses were performed in three replicates for each treatment and the results were averaged.

Cooking yield

The cooking yield was calculated from the difference between the weights of the raw and cooked samples after they were tempered to 25 °C, and expressed as a percentage of the initial weight (Boles and Swan 1996). Raw steaks were grill-cooked until the temperature at the geometric centre reached 75 °C. Four replicates were performed for each treatment and mean value was calculated.

Instrumental color analysis

Color parameters were measured using a CR 400 colorimeter (Konica Minolta Inc., Osaka, Japan) and expressed as L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness) values. Raw steaks were thawed at 4 °C for 5 h and maintained for 1 h at 25 °C to allow color development. Measurements were averaged from both planar surfaces. The grilled steaks were bisected to expose the inner surface followed by 1 h tempering at 25 °C. The color readings were averaged from both inner planar surfaces (Monteiro et al. 2013). The results were obtained from mean value of eight replicates for each treatment.

Instrumental texture analysis

Texture profile analysis (TPA) of the raw and cooked tilapia restructured steaks was performed using TA XT plus texture analyser (Stable Micro Systems Ltd., Surrey, UK) and the Texture Expert for Windows software (Stable Micro Systems), and were expressed as hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness and resistance values (Canto et al. 2012). The samples were thawed as previously described for the color analysis. The samples were compressed to 50 % of their original thickness using a 75-mm diameter cylindrical metal probe (P/75). Two compression cycles (pre-test speed: 10 mm/s; test speed: 5 mm/s and post-test speed: 10 mm/s; time between compressions: 5 s) were performed. These analyses were performed in ten replicates for each treatment and the results were averaged.

Sensory analysis

Quantitative descriptive analysis

The sensory profile of the raw and cooked products were obtained from eight trained panellists, including three men and five women between the ages of 24 and 31, using quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) (Stone et al. 1974). The panellists were students in the graduate course of the Department of Food Technology of the Universidade Federal Fluminense. The recruitment was conducted by individual oral interviews. During training, the panellists defined the attributes (color, flavor, taste and texture) with their respective descriptors, references and perception intensities (Table 2) through an open discussion among the panel members that was moderated by a leader.

Table 2.

Description and references of sensory attributes used in quantitative descriptive analysis of restructured tilapia steaks

| Sample | Attribute | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Color | Light white | Light: Raw hake fillet |

| Dark: Raw shrimp tail | |||

| Cooked | Color | Very light white | Light: Cooked shark fillet (Carcharrhinus spp.) |

| Dark: Raw tilapia fillet (internal portion) | |||

| Cooked | Tilapia flavor | Flavor characterized by tilapia meat | Slight: Grilled tilapia fillet |

| A lot: Brazilian rice spice mix (onion, garlic, and salt)—1 % | |||

| Cooked | Tilapia taste | Taste characterized by tilapia meat | Slight: Grilled tilapia fillet |

| A lot: Brazilian rice spice mix (onion, garlic, and salt)—1,75 % | |||

| Cooked | Salty taste | Taste characterized by sodium chloride | Slight: Grilled tilapia fillet |

| A lot: 3 % of NaCl in water | |||

| Cooked | Tenderness | Strength needed to shear at the first bite | Slight: Pickle tuna natural (solid) |

| A lot: Cooked shark fillet (Carcharrhinus spp.) | |||

| Cooked | Succulence | Amount of juice expelled on chewing | Slight: Pickle tuna natural (solid) |

| A lot: Cooked shark fillet (Carcharrhinus spp.) | |||

| Cooked | Cohesiveness | Tendency of meat particles to stick together | Slight: Cooked shark fillet (Carcharrhinus spp.) |

| A lot: Desalted cod | |||

| Cooked | Overall texture | Visual and textural similarity to restructured steak | Slight: Hake steak |

| A lot: Grilled tilapia fillet |

The color was evaluated in raw samples previously thawed as described for the instrumental color and texture analyses. Further attributes were evaluated after cooking the samples as described for the cooking yield analysis. After identification of the attributes and references, training with the descriptive terms was performed. Samples were cut into four pieces and presented to trained panel at 25 °C on disposable white plastic plates. All samples were evaluated under laboratory conditions and a total of 9 sessions were conducted. A cream cracker without salt and mineral water at 25 °C were offered to cleanse the palate between samples.

For the final evaluation, the trained panellists analyzed three replicates of the samples in individual booths. The samples were served in a monadic way, encoded with a three-number identifier and presented in a balanced order using a 9-cm linear non-structured quantitative perception intensity scale.

Acceptance and consumers testing

The sensory analyses were performed in individual booths by 60 untrained panellists (22 men and 38 women, between the ages of 19 and 51). The samples were evaluated after cooked as described previously. The restructured tilapia steaks were randomly presented on white plastic plates at 25 °C. The appearance, cooked color, flavor, odor, texture, succulence and overall acceptance were evaluated according to a nine-point hedonic scale (1—extremely disliked, 5—neither disliked, nor liked and 9—extremely liked) (Dornelles et al. 2009; Stone and Sidel 1998). Additionally, the salty taste, spicy taste and firmness were evaluated using a nine-point Just-About-Right (JAR) scale (1—extremely too little salty/spicy taste or firm; 5—just about right; 9—extremely too much salty/spicy taste or firm) according to Cervantes et al. (2010).

Statistical analyses

Physico-chemical, instrumental color and texture, and sensory parameters were analyzed using one-way ANOVA at 95 % of confidence level to compare the mean values for each parameter between the treatments; data was further analysed using Tukey test when means were considered different (P < 0.05). These analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism® (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). In addition, PCA statistical test was performed to verify the parameters that were influenced of determinant way with MTG increment. PLS statistical test was performed to verify if the determinant parameters contributed positively or negatively to the overall acceptance of the MTG samples. In addition, penalty analysis was performed to analyse the JAR data to identify possible alternatives for product improvement. Pearson’s correlation at a 5 % significance level (P < 0.05) was performed to correlate the instrumental and sensory data (color and texture parameters). The PCA, PLS, penalty analysis and Pearson’s correlation were performed using XLSTAT version 2012.6.08 (Addinsoft, Paris, France) software.

Results and discussion

Proximate composition

MTG did not affect (P > 0.05) the proximate composition of restructured tilapia steaks (Table 3). Our results are in agreement with Chin and Chung (2003), who reported no difference (P < 0.05) in the proximate composition of restructured meat products (sausages) manufactured with 0 % MTG or with 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 % MTG. Uran et al. (2013) studied different levels of MTG (0.5 and 1.0 %) in chicken breast patties, and observed that MTG did not affect ash, lipid and protein contents when compared to the control samples. Nonetheless, the formulation containing 1 % of MTG exhibited lower (P < 0.05) moisture content than control and the formulation containing 0.5 % of MTG. The addition of MTG induced protein cross-linking in the gel matrix, potentially enhancing the water-holding capacity of the gel (Han et al. 2009), and decreasing the moisture content (Qiao et al. 2001). Based on our results and other literature reports, the use of MTG up to 0.8 % does not affect the proximate composition.

Table 3.

Proximate composition, cooking yield, instrumental color, and textural attributes of restructured tilapia steaks

| Treatments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Parameters | ||||

| Protein (%) | 22.80a ± 0.01 | 20.95a ± 0.01 | 22.40a ± 0.00 | 22.32a ± 0.00 |

| Lipids (%) | 2.28a ± 0.00 | 2.70a ± 0.00 | 2.59a ± 0.00 | 2.66a ± 0.00 |

| Ash (%) | 2.47a ± 0.00 | 2.44a ± 0.00 | 2.52a ± 0.00 | 2.46a ± 0.00 |

| Moisture (%) | 75.07a ± 0.00 | 74.83a ± 0.00 | 74.23a ± 0.01 | 75.28a ± 0.01 |

| Cooking yield | 78.24c ± 1.31 | 83.05b ± 0.85 | 83.21b ± 1.16 | 86.21a ± 0.53 |

| Raw attributes | ||||

| Hardness | 958.0b ± 250.86 | 1553a ± 366.33 | 1734a ± 225.87 | 1307a ± 388.87 |

| Springiness | 0.8005a ± 0.09 | 0.7795a ± 0.02 | 0.7025b ± 0.02 | 0.6785c ± 0.05 |

| Cohesiveness | 0.3880a ± 0.08 | 0.3815a ± 0.03 | 0.4270a ± 0.03 | 0.3575a ± 0.04 |

| Chewiness | 481.3a ± 98.75 | 299.3b ± 41.94 | 241.1b ± 18.11 | 235.6b ± 48.76 |

| Resistance | 0.1430b ± 0.02 | 0.1530b ± 0.01 | 0.1860a ± 0.03 | 0.1475b ± 0.02 |

| L* | 56.01a ± 0.56 | 57.29a ± 1.28 | 56.21a ± 1.16 | 56.19a ± 0.47 |

| a* | 6.65a ± 0.26 | 6.30a ± 0.29 | 6.57a ± 0.31 | 6.68a ± 0.25 |

| b* | 7.27a ± 0.43 | 7.66a ± 0.51 | 7.39a ± 0.47 | 7.44a ± 0.28 |

| Cooked attributes | ||||

| Hardness | 1900a ± 154.39 | 1795b ± 160.97 | 1772b ± 152.88 | 1724b ± 171.13 |

| Springiness | 0.6250a ± 0.06 | 0.6015a ± 0.01 | 0.6650a ± 0.02 | 0.6485a ± 0.01 |

| Cohesiveness | 0.2815a ± 0.03 | 0.2665a ± 0.00 | 0.2810a ± 0.02 | 0.3195a ± 0.04 |

| Chewiness | 337.9a ± 77.51 | 291.8b ± 43.66 | 267.1b ± 62.97 | 224.9c ± 48.40 |

| Resistance | 0.0805a ± 0.01 | 0.0920a ± 0.00 | 0.0945a ± 0.01 | 0.0895a ± 0.02 |

| L* | 63.65a ± 2.57 | 62.55a ± 2.45 | 61.31a ± 1.48 | 60.94a ± 1.96 |

| a* | 5.67b ± 0.88 | 5.44a ± 0.87 | 5.67ab ± 0.84 | 5.60b ± 0.88 |

| b* | 14.09bc ± 1.25 | 15.97a ± 1.48 | 15.50ab ± 1.53 | 12.96c ± 0.99 |

Values are means ± SD

CON (0 % MTG); T1 (0.1 % of MTG); T2 (0.5 % of MTG); T3 (0.8 % of MTG)

L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness)

Different letters in the same line indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

Bacteriological analysis

Salmonella spp. and Staphylococcus aureus were not detected in the samples. The total coliform, thermotolerant coliform, Escherichia coli, Enterobacteriaceae, TAMB, and TAPB concentrations were within the official limits (ICMSF 1986) for raw materials and in all of the treatments, indicating rather low bacterial contents in the products. CON, T1, T2 and T3 contained exhibited 3.0–3.5 Log CFU/g of TAMB and 2.0–3.0 Log CFU/g of Enterobacteriaceae in all of the treatments. Furthermore, CON, T1, T2 and T3 contained TAPB concentrations < 3 Log CFU/g (P > 0.05). This suggests that, under controlled conditions, the bacterial safety of restructured tilapia steaks was not compromised by the addition of the ingredients and the manufacture procedure.

Frozen storage monitoring

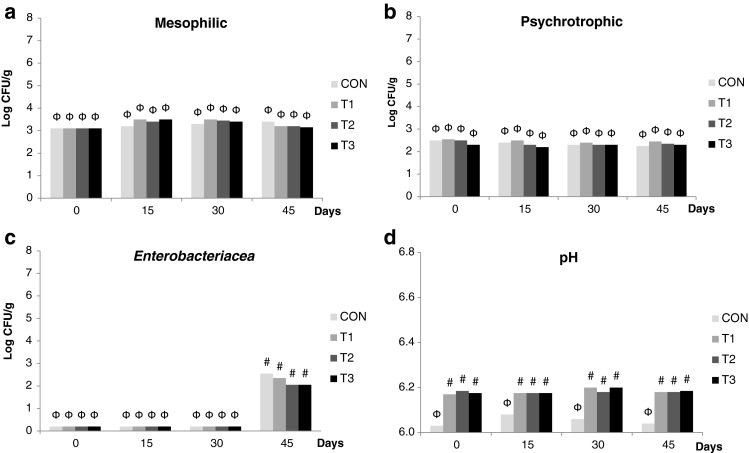

The TAMB (Fig. 1a) and TAPB (Fig. 1b) counts remained constant (P > 0.05) during the frozen storage, suggesting that MTG did not affect the growth rate of these microorganisms. All samples exhibited similar bacterial loadings (3.0–3.5 and 2.0–2.5 Log CFU/g for TAMB and TAPB, respectively) at the end of experiment, demonstrating that the bacterial quality of the samples was not compromised. Figure 1c illustrates a minimal growth (< 1 Log CFU/g) of Enterobacteriaceae until the 30th day of frozen storage. The Enterobacteriaceae bacterial loading increased (P < 0.05) at 45 days, reaching values between 2.0 and 3.0 Log CFU/g in all treatments. The observed initial reduction of Enterobacteriaceae bacterial load until the 30th day is potentially due to cell injury caused by the frozen storage with posterior adaptation at 45 days. The bacterial concentrations in all treatments were within the range limits established by the International Commission on Microbiological Specification for Foods (ICMSF 1986).

Fig. 1.

Behavior of mesophilic (a), psychrotrophic (b), Enterobacteriaceae (c) and pH (d) of restructured tilapia steaks during frozen storage. CON (0 % MTG); T1 (0.1 % of MTG); T2 (0.5 % of MTG); T3 (0.8 % of MTG). Different symbols over the bars indicate significant differences between of storage periods and; CON and MTG-treatments (P < 0.05)

The pH values (Fig. 1d) were not affected (P > 0.05) by the storage period. However, the observed greater (P < 0.05) pH values in T1, T2 and T3 than CON, was not dependent of the storage time. This result is potentially due to the chemical reactions catalysed by MTG involving water molecules in the food matrix. This enzyme improves the water-holding capacity of proteins either by increasing their ability to swell and bind water or by inducing the formation of a gel sieve entrapping the water molecules (Ionescu et al. 2008). Moreover, in the absence of amine substrates, transglutaminase is capable of catalysing the deamination of glutamine residues, where water is used as a nucleophile and ammonia is liberated, resulting in alkalization of the medium (Macedo et al. 2010). In agreement with our results, Han et al. (2009) suggested that MTG potentially promoted an increased in the pH values of pork myofibrillar proteins.

Cooking yield

The CON tilapia steaks exhibited a lower (P < 0.05) cooking yield (78.24) than the other treatments (Table 3). Amongst the MTG treated steaks, T3 had the highest (P < 0.05) cooking yield (86.21 %), potentially due to the MTG-induced strong protein interactions, improving the water-holding capacity and consequently, increasing the cooking yield (Suksomboon and Rawdkuen 2010). Our data were consistent with previous studies investigating the effect of MTG on the physico-chemical parameters of chicken meat-balls (Tseng et al. 2000), pork batter gels (Pietrasik and Li-Chan 2002), pork myofibrillar proteins (Han et al. 2009), and ostrich meat-balls (Suksomboon and Rawdkuen 2010). In accordance with the results of this study, Puolanne and Peltonen (2013) reported that a higher water-holding capacity can be obtained by increasing the pH value in meat products.

Texture measurements

Raw restructured tilapia steaks

MTG increased hardness (P < 0.05), nonetheless it decreased springiness and chewiness (Table 3). T3 exhibited the lowest (P < 0.5) springiness amongst all treatments. Cohesiveness was not affected by the MTG addition (P > 0.05). In agreement with our results, Uresti et al. (2003) observed that the addition of 0.1 and 0.3 % of MTG in fish gel decreased its chewiness; furthermore, the addition of 0.3 % of MTG increased springiness. Ramírez et al. (2006) reported that hardness was increased while cohesiveness was not affected when 0.3 % of MTG was added to restructured fish products. In addition, Moreno et al. (2010a) observed that restructured trout minced meat treated with 1.0 % MTG had greater hardness than their control counterparts. In contrast, adding MTG (to 0.1 and 0.3 %) decreased the hardness of fish gels (Uresti et al. 2003), 0.3 % MTG had no effect on the springiness of restructured fish products (Ramírez et al. 2006) and 1.0 % MTG increased the cohesiveness of restructured trout mince (Moreno et al. 2010a).

The increased hardness observed in the restructured tilapia steaks containing MTG is potentially due to MTG-induced proteins cross-linking (Moreno et al. 2010b; Ramírez et al. 2006). Small quantities of MTG (0.1 %) improve the meat pieces cohesion (Heinz and Hautzinger 2007). Moreno et al. (2010a) concluded that a concentration of 0.5 % MTG was sufficient to obtain satisfactory mechanical properties in restructured raw hake products.

Cooked restructured tilapia steaks

After cooking, T1, T2, and T3 steaks exhibited lower (P < 0.05) hardness and chewiness than CON ones (Table 3). This result could be linked to the greater cooking yield promoted by MTG addition. According to Sen (2005), one of the most important factors of the eating quality of meat is texture, which is mainly governed by water–protein interactions. No differences (P > 0.05) were observed in springiness, cohesiveness and resistance amongst all treatments. This study suggests that MTG (up to 0.8 %) could improve the mechanical properties of restructured tilapia steaks, even at low salt level (1.5 %).

Although MTG activity occurs independently from the presence of salts and protein isolates, these ingredients are commonly used to increase the protein extractability and concentration, thereby improving the activity of MTG (Jarmoluk and Pietrasik 2003). Ramírez et al. (2000) investigated the effect of NaCl concentration in the myosin aggregation and documented that myofibrillar proteins require at least 2.0 % salt for optimal solubilisation. Ham-like products manufactured using restructured carp meat (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) manufactured using a massaging technique (Ramírez et al. 2002) exhibited greater mechanical properties when the proteins were solubilised with 2.0 % of salt than when solubilised with 1.0 % of salt. Nevertheless, the addition of MTG, followed by controlled heating, considerably improved the textural properties of fish minced meat when different matrices and experimental conditions were applied. This indicates that MTG enzymes exhibit species-specific activity and temperature optima, which may be related to the temperature of the fish habitat and the degree of purity of the enzyme (Binsi and Shamasundar 2012).

Instrumental colour measurements

Raw restructured tilapia steaks

No differences (P > 0.05) in L*, a*, and b* values were observed amongst all treatments (Table 3). In accordance with our results, Uresti et al. (2003), Chin and Chung (2003), and Uran et al. (2013) reported no differences (P > 0.05) in the color parameters of fish gels, restructured meat and chicken breast patties treated with different levels of MTG (0.5–1.0 %), respectively. Moreno et al. (2008) documented that to prevent color changes in meat products, the enzyme must react at approximately 5 °C for up to 48 h. These conditions are similar to those used in our study.

Cooked restructured tilapia steaks

There was no difference in the lightness values amongst the treatments (P > 0.05; Table 3). Nonetheless, T1 exhibited greater (P < 0.05) a* and b* values when compared to CON. In agreement with our results, Cofrades et al. (2011) reported that the cooking process decreases the redness and increases the lightness and yellowness, resulting in a whiter coloration in restructured poultry. Although differences in the measured color values of cooked restructured tilapia steaks were observed, our data demonstrate that the addition of MTG did not negatively affect the lightness of the MTG-treated product. Additionally, light color is one of the most important visual traits of tilapia product perceived by consumers (Medri et al. 2009). Therefore, the results indicate the application potential of these MTG concentrations in restructured tilapia steaks.

Quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA)

T1 exhibited lower (P < 0.05) tilapia flavor and tilapia taste than other treatments (Table 4). Salty taste and succulence were increased by MTG addition, regardless of the concentration used. T1, T2, and T3 exhibited a greater (P < 0.05) tenderness and lower (P < 0.05) cohesiveness than CON. There were no differences (P > 0.05) in the raw color, cooked color or overall texture amongst all treatments. QDA is of great importance in food product development because it is performed with trained panellists (Resurreccion 2003). In our study, a salty taste, succulence and tenderness were considered to be relevant sensory traits for the development of restructured tilapia steaks. Han et al. (2009) suggested that MTG increases the water-holding capacity of proteins, potentially improving textural attributes, such as succulence and tenderness. Dimitrakopoulou et al. (2005) reported that MTG did not negatively affect firmness, succulence, color, aroma, taste, and saltiness of restructured pork shoulder; nonetheless, it improved the consistency and overall acceptability. Our data are in accordance with those of Moreno et al. (2010b), who observed that samples containing 1.5 % NaCl and 1.0 % MTG exhibited greater succulence than the other treatments (0.5–4.0 % NaCl and 0.5–1.0 % MTG).

Table 4.

Quantitative descriptive analysis, consumer sensory and Just-About-Right profile scores of restructured tilapia steaks

| Treatments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| QDA attributes | ||||

| Raw color | 6.87a ± 0.65 | 6.85a ± 0.68 | 6.93a ± 0.65 | 6.87a ± 0.72 |

| Cooked color | 2.35a ± 0.29 | 2.35a ± 0.35 | 2.32a ± 0.29 | 2.31a ± 0.30 |

| Tilapia flavor | 7.17a ± 0.50 | 6.68b ± 0.77 | 7.02ab ± 0.78 | 7.47a ± 0.48 |

| Tilapia taste | 7.29a ± 0.43 | 6.53b ± 0.71 | 7.05a ± 0.62 | 7.47a ± 0.68 |

| Salty taste | 5.83c ± 0.60 | 6.34b ± 0.46 | 6.34b ± 0.45 | 7.45a ± 0.94 |

| Tenderness | 7.40b ± 0.61 | 7.67a ± 0.45 | 7.76a ± 0.65 | 7.68a ± 0.39 |

| Succulence | 6.87b ± 1.01 | 7.12ab ± 0.60 | 7.51a ± 0.75 | 7.81a ± 0.49 |

| Cohesiveness | 2.78a ± 0.58 | 2.39b ± 0.25 | 2.17b ± 0.51 | 2.16b ± 0.61 |

| Overall texture | 6.67a ± 0.54 | 6.59a ± 0.80 | 6.39a ± 1.08 | 6.55a ± 0.94 |

| Consumer attributes | ||||

| Appearance | 7.18a ± 1.21 | 7.13a ± 1.42 | 7.28a ± 1.39 | 7.52a ± 1.07 |

| Cooked color | 7.15a ± 1.34 | 7.13a ± 1.37 | 7.23a ± 1.32 | 7.28a ± 1.22 |

| Flavor | 6.90a ± 1.35 | 6.93a ± 1.29 | 7.18a ± 1.20 | 7.48a ± 1.23 |

| Taste | 6.92a ± 1.24 | 7.10a ± 1.34 | 7.40a ± 1.15 | 7.48a ± 1.44 |

| Texture | 7.32a ± 1.40 | 7.35a ± 1.26 | 7.67a ± 0.91 | 7.67a ± 0.97 |

| Succulence | 6.98b ± 1.13 | 7.07b ± 1.25 | 7.43a ± 1.17 | 7.63a ± 1.01 |

| Overall acceptance | 7.12b ± 1.01 | 7.13b ± 1.03 | 7.48a ± 0.98 | 7.52a ± 0.98 |

| JAR attributes | ||||

| Salty taste | 5.05b ± 1.02 | 5.13ab ± 1.35 | 5.30ab ± 0.93 | 5.60a ± 1.14 |

| Spicy taste | 4.87b ± 0.98 | 4.87b ± 1.03 | 5.08ab ± 0.83 | 5.55a ± 1.23 |

| Firmness | 5.02a ± 0.77 | 5.07a ± 0.99 | 5.37a ± 0.84 | 5.38a ± 1.11 |

Values are means ± SD

CON (0 % MTG); T1 (0.1 % of MTG); T2 (0.5 % of MTG); T3 (0.8 % of MTG)

Different letters in the same line indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) explained 84.25 % of total data variance (Fig. 2) in which texture and taste attributes were the most relevant. This result supports the QDA data. The first principal component, PC1, represented 48.07 % of the total variation whereas the second principal component described 36.18 % of the total variation. MTG treatments (T1, T2 and T3) were outlined by greater salty taste, tenderness and succulence values, with lower cohesiveness than CON. Additionally, salty taste, tenderness, succulence and cohesiveness, perceived by the consumers in the QDA, were highly correlated with both principal components, indicating that these were the relevant parameters for differentiating the treatments.

Fig. 2.

Instrumental and sensory data of restructured tilapia steaks in the plane defined by two principal components. CON (0 % MTG); T1 (0.1 % of MTG); T2 (0.5 % of MTG); T3 (0.8 % of MTG)

The Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicated a strong association amongst cooking yield, textural and sensory attributes. The most important correlations were between cooking yield and sensory attributes were tenderness (r = 0.83), succulence (r = 0.91), salty taste (r= 0.91), and between sensory salty taste and sensory succulence (r = 0.90). These results explain the greater tenderness and succulence of the MTG-treatments, which provided a greater cooking yield when compared to CON as well as a greater salty taste, which were highly correlated to succulence. According to Desmond (2006), the increase in the water-holding capacity of meat positively affects the cooking yield, thereby increasing tenderness and succulence of the meat product. Moreover, this study indicates a possible relation between the salty taste and the cooking yield, suggesting that the addition of MTG as well as salt potentially improve the water-holding capacity and the perceived saltiness, which positively contribute to the overall acceptance (Monteiro et al. 2013). In addition, were documented correlation between sensory cohesiveness and sensory tenderness (r = −0.95), and sensory cohesiveness and sensory succulence (r = −0.91). Cohesiveness is determined as the amount of product deformation rather than its rupture when forces are applied (Civille 2011). The negative correlation between the textural parameters (cohesiveness, tenderness and succulence) found in this study, suggests an inverse relationship where the increase on succulence and tenderness, is associated with a decrease in cohesiveness.

Consumers’ sensory testing

Hedonic scale testing

All of the treatments received high scores (above 7.0) for the assessed attributes, except for flavour, taste and succulence in CON, and flavour in T1(Table 4). No differences (P > 0.05) were observed in appearance, cooked color, flavor, taste and texture attributes amongst all treatments, indicating that untrained panellists could not differentiate between CON and MTG-treated steaks based on these attributes. Additionally, T2, and T3 were rated with greater (P < 0.05) succulence and overall acceptance scores than control and T1, regardless of the MTG concentration. This fact potentially occurred due to the lower hardness and chewiness and greater cooking yield and tenderness values of T2 and T3 contributing to greater acceptability. CON exhibited greater sensory cohesiveness than the other treatments, and this attribute was negatively correlated to sensory tenderness (r = −0.95) and sensory succulence (r = −0.91). This result may have been a determinant factor for the lower acceptability of CON steaks. In general, tenderness and succulence of muscle foods strongly influence and drive consumer’s acceptability, and are considered the major factors that determine the eating quality of meat (Brewer and Novakofski 2008).

The consumer test revealed that 88, 90 and 88 % of the consumers would purchase T1, T2 and T3 steaks, respectively. Similarly, CON would be purchased by 76 % of the consumers. These results suggest that the addition of MTG improved the purchase intention of the restructured tilapia steaks and some of their sensory proprieties (succulence, salty taste and tenderness) were essential for product acceptability by the consumer. The MTG can be used to improve the textural, functional and sensorial properties of meat products to appropriate for commercialisation (Ramírez et al. 2007).

Our results showed that MTG improves the acceptability of restructured tilapia steaks prepared using sub-ideal weight tilapia fillets, representing an alternative for the fish industry. In agreement our results, Gonçalves and Passos (2010) reported that a restructured fish product of white croacker containing MTG was positively perceived by consumers in regard to its appearance, flavor, taste and texture traits. Mahmood and Sebo (2009) observed better results in some attributes as colour, texture, flavour and consistency of cheese with 0.6 % of MTG when compared with control samples.

Just-about-right (JAR) profile

T1, T2 and T3 had a salty taste and a spicy taste that increased with the increase of the MTG levels (Table 4). Despite this fact, these attributes were close to ideal in all treatments (JAR = 5.60, and 4.87 to 5.55, respectively). Firmness values were close to ideal (JAR = 5.02 to 5.38) and no difference (P > 0.05) was observed amongst the treatments. This result suggests that the consumers were unable to differentiate the restructured tilapia steaks manufactured with different MTG levels based on their texture. Moreno et al. (2010a) concluded that the MTG content (0.5 and 1.0 %) did not affect the sensorial firmness of cooked raw hake samples. They concluded that cooking the preparation at 70–80 °C was sufficient to establish enough bonds to maintain the firmness of products restructured from raw hake muscle, particularly when the samples contained 1.5 % NaCl or more.

Partial least squares regression (PLSR)

Figure 3 shows the relationships amongst QDA and instrumental parameters that contributed to the overall acceptance obtained using PLSR. The PLSR model explained 100.0 % of the consumer acceptance (Y-axis) and 84.1 % of the trained panellists sensory scores and the instrumental parameters (X-axis), yielding an accumulated Q2 of 0.980. The QDA and instrumental attributes were considered relevant when their respective variable importance in the projection was greater than 1.0 (Wold et al. 2001).

Fig. 3.

Partial Least Square regression model for sensory and instrumental attributes of restructured tilapia steaks. X axis = instrumental and sensory attributes; Y axis = consumer acceptance. CON (0 % MTG); T1 (0.1 % of MTG); T2 (0.5 % of MTG); T3 (0.8 % of MTG)

Several sensory attributes (cooked color, cohesiveness and overall texture), instrumental cooked hardness, and several color parameters (raw b*, raw L* and cooked L* values) were detrimental to the overall acceptance, whereas other sensory attributes (salty taste, tenderness and succulence), several texture parameters (cooked cohesiveness and cooked springiness) and cooking yield positively contributed to the overall acceptance (Fig. 4). In relation to the last parameters, T1 exhibited a lower cooked cohesiveness and cooked springiness than CON, T2 and T3, but this difference was not perceived by the consumers. In contrast, the consumers considered T1, T2 and T3 more salty, tender and succulent potentially due to greater cooking yield. These data suggest that the addition of MTG improved these sensory attributes; therefore, MTG improved the overall acceptance of the restructured tilapia steaks. In agreement with our results, Uran et al. (2013) evaluated the addition of 0.5 and 1.0 % of MTG in chicken breast patties and concluded that these MTG concentrations increased the cooking yield and improved textural properties.

Fig. 4.

Weighted regression coefficients of instrumental and sensory parameters detrimental to consumer acceptance by partial least squares regression

Penalty analysis

Penalty analysis was applied to sensory data to identify the parameters (individually for each treatment) that can be improved to increase consumer acceptance, by combining the data from JAR profile and consumers’ hedonic testing. The major detrimental attributes were those with >0.5 penalty score and >20 % occurrence. The firmness value penalised the overall acceptance of T2 and was perceived by 33 % of the consumers. This result was possibly related to the increased raw and cooked resistance in T2 steaks. The consumers described these steaks as slightly more firm than ideal (JAR = 5.37). T3 was penalised for a too spicy taste by 33 % of the consumers. Moreover, the consumers concluded that these steaks were slightly spicier than ideal (JAR = 5.55). Apparently, the high MTG level of this treatment contributed to enhance the spiciness perception. However, the consumers were not able to differentiate the treatments based on their texture and taste attributes; T2 and T3 had a greater overall acceptance (7.48 and 7.52, respectively) than other treatments. The salty taste did not penalise the overall acceptance of any treatments (CON, T1, T2 and T3), suggesting that this attribute positively contributed to the steaks acceptability.

Conclusions

The utilization of MTG in the development of restructured meat products is a viable tool for the food industry. This enzyme maintained the proximal composition and nutritional characteristics and improved the sensorial and textural attributes of the product. These advantages can be achieved by using a low concentration of MTG (0.5 %) in the product formulation. The restructured tilapia steak prepared from sub-ideal weights fillets is a potential valued-added product with good acceptance and better purchase intention than steaks prepared with 0 % MTG.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support in the State of Rio de Janeiro—FAPERJ (projects E-26/111.196/2011, E-26/103.003/2012 and E-26/111.673/2013) for financial support. We thank the regional cooperative (COOPERCRAMMA) for providing the samples and Ajinomoto for providing the MTG Activa enzyme. M.L.G. Monteiro would like to thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq (project 551079/2011-8) for financial support.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 16. Washington DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- APHA . Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods. 4. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Binsi PK, Shamasundar BA. Purification and characterization of transglutaminase from four fish species: effect of added transglutaminase on the viscoelastic behaviour of fish mince. Food Chem. 2012;132:1922–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boles JA, Swan JE. Effect of post-slaughter processing and freezing on the functionality of hot-boned meat from young bull. Meat Sci. 1996;44:11–18. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(96)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MS, Novakofski JE. Consumer quality evaluation of aging of beef. J Food Sci. 2008;73:S78–S82. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto ACVCS, Lima BRCC, Cruz AG, Lázaro CA, Freitas DGC, Faria JAF, Torrezan R, Freitas MQ, Silva TPJ. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on the color and texture parameters of refrigerated Caiman (Caiman crocodilus yacare) tail meat. Meat Sci. 2012;91:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes BG, Aoki NA, Almeida CPM. Sensory acceptance of fermented cassava starch biscuit prepared with flour okara and data analysis with penalty analysis methodology. Braz J Food Technol. 2010;19:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chin KB, Chung BK. Utilization of transglutaminase for the development of low-fat, low-salt sausages and restructured meat products manufactured with pork ham and loins. Asian Aust J Anim Sci. 2003;16:261–265. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2003.261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Civille GV. Food texture: pleasure and pain. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:1487–1490. doi: 10.1021/jf100219h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofrades S, López-López I, Ruiz-Capillas C, Triki M, Jiménez-Colmenero F. Quality characteristics of low-salt restructured poultry with microbial transglutaminase and seaweed. Meat Sci. 2011;87:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte-Júnior CA, Fernández M, Mano SB. Use of carbon dioxide to control the microbial spoilage of bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) meat. In: Mendez-Vilas A, editor. Modern multidisciplinary applied microbiology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2008. pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Conte-Júnior CA, Peixoto BTM, Lopes MM, Franco RM, Freitas MQ, Fernández M, Mano SB. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on the growth/survival of Yersinia enterocolitica and natural flora on fresh poultry sausage. In: Méndez-Vilas A, editor. Current research, technology and education topics in applied microbiology and microbial biotechnology. Badajoz: Formatex; 2010. pp. 1217–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzo-Siqueira A, Oetterer M. Effects of irradiation and refrigeration on the nutrients and shelf-life of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) J Aquat Food Prod Technol. 2003;12:85–101. doi: 10.1300/J030v12n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond E. Reducing salt: a challenge for the meat industry. Meat Sci. 2006;74:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou MA, Ambrosiadis JA, Zetou FK, Bloukas JG. Effect of salt and transglutaminase (TG) level and processing conditions on quality characteristics of phosphate-free, cooked, restructured pork shoulder. Meat Sci. 2005;70:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelles AS, Rodrigues S, Garruti DS. Aceitação e perfil sensorial das cachaças produzidas com Kefir e Saccharomyces cerevisae. Cienc Tecnol Aliment. 2009;29:518–522. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612009000300010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J, Gunning Y, FitzGerald RJ. Effect of cross-linking with transglutaminase on the heat stability and some functional characteristics of sodium caseinate. Food Res Int. 2003;36:267–274. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(02)00168-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves AA, Passos MG. Restructured fish product from white croacker (Micropogonias furnieri) mince using microbial transglutaminase. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2010;53:987–995. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132010000400030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Zhang Y, Fei Y, Xu X, Zhou G. Effect of microbial transglutaminase on NMR relaxometry and microstructure of pork myofibrillar protein gel. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;228:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s00217-008-0976-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz G, Hautzinger P (2007) Meat processing technology for small- to medium-scale producers, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations regional office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok. http://www.fao.org/. Available at. Accessed 9 March 2013

- ICMSF . Microorganisms in foods, sampling for microbiological analysis: principles and specific applications. 2. Toronto: International Commission on the Microbiological Specifications for Foods; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu A, Aprodu I, Daraba A, Porneala L. The effects of transglutaminase on the functional properties of the myofibrillar protein concentrate obtained from beef heart. Meat Sci. 2008;79:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmoluk A, Pietrasik Z (2003) Response surface methodology study on the effects of blood plasma, microbial transglutaminase and k-carrageenan on pork batter gel properties. J Food Eng 60:327–334

- Jiang ST, Hsieh JF, Ho ML, Chung YC. Microbial transglutaminase affects gel properties of golden threadfin-bream and pollack surimi. J Food Sci. 2000;65:694–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16074.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A. Crescimento heterogêneo em tilápias cultivadas em tanque rede e submetidas a classificações periódicas. Rev Bras Eng Pesca. 2008;3:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo JA, Cavallieri ALF, Cunha RL, Sato HH. The effect of transglutaminase from Streptomyces sp. CBMAI 837 on the gelation of acidified sodium caseinate. Int Dairy J. 2010;20:673–679. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2010.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood WA, Sebo NH. Effect of microbial transglutaminase treatment on soft cheese properties. Mesopotamia J Agric. 2009;37:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Medri V, Medri W, Caetano Filho M. Growth of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fed diets with different levels of proteins of yeast. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2009;52:721–728. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132009000300024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merck . Microbiology manual. 11. Darmstadt: Merck KGoA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro MLG, Mársico ET, Teixeira CE, Mano SB, Conte-Júnior CA, Vital HC. Validade comercial de filés de Tilápia do Nilo (Oreochromis niloticus) resfriados embalados em atmosfera modificada e irradiados. Ciênc Rural. 2012;42:737–743. doi: 10.1590/S0103-84782012000400027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro MLG, Mársico ET, Canto ACVCS, Costa Lima BRC, Lázaro CA, Cruz AG, Conte-Júnior CA (2013) Partial sodium replacement in value-added product of tilapia without loss of acceptability. J Food Sci (submitted) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moreno HM, Carballo J, Borderías AJ. Influence of alginate and microbial transglutaminase as binding ingredients on restructured fish muscle processed at low temperature. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88:1529–1536. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno HM, Borderías AJ, Baron CP. Evaluation of some physico-chemical properties of restructured trout and hake mince during cold gelation and chilled storage. Food Chem. 2010;120:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno HM, Carballo J, Borderías AJ. Gelation of fish muscle using microbial transglutaminase and the effect of sodium chloride and pH levels. J Muscle Foods. 2010;21:433–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MPA (2012) Boletim Estatístico da Pesca e Aquicultura, Ministério da Pesca e Aquicultura http://www.mpa.gov.br/. Available at. Accessed 9 March 2013

- Pietrasik Z, Li-Chan ECY. Response surface methodology study on the effects of salt, microbial transglutaminase and heating temperature on pork batter gel properties. Food Res Int. 2002;35:387–396. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00133-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puolanne E, Peltonen J. The effects of high salt and low pH on the water-holding of meat. Meat Sci. 2013;93:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao M, Fletcher DL, Smith DP, Northcutt JK. The effect of broiler breast meat color on pH, moisture, water-holding capacity, and emulsification capacity. Poult Sci. 2001;80:676–680. doi: 10.1093/ps/80.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez JA, Martín-Polo MO, Bandman E. Fish myosin aggregation as affected by freezing and initial physical state. J Food Sci. 2000;65:556–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16047.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez JA, Uresti RM, Téllez-Luis SJ, Vázquez M. Using salt and microbial transglutaminase as binding agents in restructured fish products resembling hams. J Food Sci. 2002;67:1778–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08722.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez JA, Del Ángel A, Velázquez G, Vázquez M. Production of low-salt restructured fish products from Mexican flounder (Cyclopsetta chittendeni) using microbial transglutaminase or whey protein concentrate as binders. Eur Food Res Technol. 2006;223:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-0210-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez JA, Velázquez G, Echevarría GL, Torres JA. Effect of adding insoluble solids from surimi wash water on the functional and mechanical properties of pacific whiting grade A surimi. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:2148–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resurreccion AVA. Sensory aspects of consumer choices for meat and meat products. Meat Sci. 2003;66:11–20. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanh T, Sezgin E, Deveci O, Senel E, Benli M. Effect of using transglutaminase on physical, chemical and sensory properties of set-type yoghurt. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25:1477–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen DP. Advances in fish processing technology. 1. India: New Delhi; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Soccol MCH, Oetterer M, Gallo CR, Spoto MHF, Biato DO. Effects of modified atmosphere and vacuum on the shelf life of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fillets. Braz J Food Technol. 2005;8:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stone H, Sidel JL. Quantitative descriptive analysis: developments, applications, and the future. Food Technol. 1998;5:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stone H, Sidel JL, Oliver S, Woosley A, Singleton RC. Sensory evaluation by quantitative descriptive analysis. Food Technol. 1974;28:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Suksomboon K, Rawdkuen S. Effect of microbial transglutaminase on physicochemical properties of ostrich meat ball. As J Food Ag-Ind. 2010;3:505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng TF, Liu DC, Chen MT. Evaluation of transglutaminase on the quality of low-salt chicken meat-balls. Meat Sci. 2000;55:427–431. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(99)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uran H, Aksu F, Yi̇lmaz İ, Durak MZ. Effect of transglutaminase on the quality properties of chicken breast patties. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2013;19:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Uresti RM, Ramírez JA, López-Ariasa N, Vázquez M. Negative effect of combining microbial transglutaminase with low methoxyl pectins on the mechanical properties and colour attributes of fish gels. Food Chem. 2003;80:551–556. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00343-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidotti RM, Gonçalves GS (2006) Produção e caracterização de silagem, farinha e óleo de tilápia e sua utilização na alimentação animal. Instituto de Pesca. http://www.pesca.sp.gov.br. Available at. Accessed 15 March 2013

- Wold S, Sjostrom M, Eriksson L. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemometr Intell Lab. 2001;58:109–130. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7439(01)00155-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]