Abstract

Lipids, especially unstable ones with health beneficiary effects, need to be converted into stable ingredients through nanoencapsulation in a liquid form by development of a nanoemulsion. The primary necessity for synthesis of such nanoemulsions is the development of a formulation for stabilizing the emulsion. Thus parameters to obtain such a stable nanoemulsions were optimized. Hence parameters like temperature, pH and electrolyte concentrations were optimized with respect to different oil:emulsifier ratios (10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 25:1 and 30:1) using sodium alginate, a polysaccharide, as encapsulant and calcium caseinate, a protein, as the emulsifier. Optimization of these process parameters were done based on different physico-chemical techniques like particle-size, zeta-potential, viscosity, lipid content and retention of fatty acid composition by the emulsified oil. Those emulsions which showed maximum resistance to stress and retained minimum particle-size, maximum stability and highest core material retention under stressed conditions were 15:1 and 10:1 emulsion systems. Of the two, 15:1 emulsion system was preferred due to its lower emulsifier requirement. Hence finally the optimized parameters which contributed to the development of the stable emulsions were alkaline pH, temperature of up to 50 ºC and electrolyte concentrations of up to 100 mM.

Keywords: Nanoemulsion, Particle-size, Zeta-potential, Viscosity, Lipid content

Introduction

In the development of food-grade delivery systems, nanoemulsion has found immense importance. The process involves the development of a stable nanoemulsion which serves as an alternative colloidal drug or biomaterial delivery system. By this technique, delivery of lipophilic bioactive components can be conveniently achieved at their targeted site along with protection of the nutriceuticals present as the core material lipids (Milane et al. 2008).

Development of nanoemulsion is the new and emerging technology dealing with the application, production and processing of materials with sizes between 100 nm to 1,000 nm (Sanguansri and Augustin 2006). Emulsification mechanism is the process in which an emulsion is formed by the rapid mixing of an organic and an aqueous phase where the composition of the initial organic phase is of immense importance (Bouchemal et al. 2004). An essential disadvantage in the development of a nanoemulsion is that it is not thermodynamically stable (McClements 2012). It is therefore important to analyze and fabricate the factors that impact the stability of the nanoemulsion. Even though different types of emulsions may be used, oil/water emulsions are of interest because they use water as the nonsolvent, which simplifies process economics as it eliminates the need for recycling and minimizes agglomeration (Aftabrouchard and Dorlker 1999).

Caseinates are often used as an effective emulsion stabilizer for fats. Calcium caseinate stabilizes emulsions as their chemical structure helps to interact with the fat phase leading them to play a vital role in fat retention (Holcomb et al. 1990). Moreover calcium caseinate has an HLB value of about 10 and hence it acts as an effective oil-in-water emulsifier (Srinivasan et al. 1999). Hence this food grade emulsifier was chosen for this work. During preparation of cheese analogs using calcium caseinate, high degree of casein dissociation was noted at high temperatures (Cavalier-Salou and Cheftel 1991). Thus in the following study a low temperature was maintained throughout to inhibit protein degradation. The orthokinetic stability of emulsions increased with increasing caseinate concentrations when calcium induced oil-in-water emulsions were prepared (Schokker and Dalgleish 2000). In fact presence of calcium ions in caseinate stabilized emulsions lead to pronounced reduction of viscosity (Radford et al. 2004). However the optimum limit of the emulsifier, needed to stabilize such oil-in-water emulsions is still not well defined. So in work starting from a very low concentration to gradually increasing concentrations of the emulsifier. Sodium alginate is a GRAS natural polymer used in drug delivery formulations as an encapsulant due to their excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability (Shu and Zhu 2002). They are known to interact with proteins such as caseinates to develop a rigid protein-polymer network which promotes interfacial stabilization of the oil-in-water emulsions (Reis et al. 2005).

In the present work, a nanoemulsion was developed using a protein emulsifier (calcium caseinate) and a polysaccharide encapsulant (sodium alginate). It is well known that nanoemulsions consist of basically miniature sized droplets consisting of a liquid core enveloped in a well defined membrane. However such droplets in the form of aqueous dispersions would enhance the bioavailability, ease of application and will reduce production costs. Hence an attempt was made to develop nanoemulsions which would remain stable for prolonged time periods. The emulsification conditions for development of such a system were optimized with respect to parameters like temperature, pH, and electrolyte concentrations based on factors such as lipid compositions, emulsion particle-size, stability, core lipid content etc. which can be tuned by the manufacturer. India is considered to be one of the original centers of rice cultivation where apart from its food application the oil extracted from its bran makes India the largest producer of rice bran oil. Besides its low price and easy availability the health benefits of rice bran oil have lead us to consider a means of targeted delivery of the useful nutraceuticals present in the oil along with increasing its bioavailability. Thus antioxidants in rice bran oil like oryzanol, tocopherol, tocotrienol and phytosterols need to be delivered in a controlled and specific manner to achieve their maximum health benefit. The best technique that can be adopted for fulfilling these requirements is by the development of a nanoemulsion based on rice bran oil. Hence the objective of the present work was to optimize the parameters for the formation of a stable oil-in-water nanoemulsion containing a solid, hydrophilic encapsulant, in terms of thermal, pH and electrolyte sensitivity, using rice bran oil as the ‘model’ core material. The parameters were optimized by characterization of the emulsions on the basis of smallest particle-size and highest stability measured in terms of zeta-potential. Hence the optimum parameters required for the development of a stable nanoemulsion based on different oil:emulsifier proportions were established. From this study, hence, the minimum amount of emulsifier needed to prepare such an emulsion was also inferred.

Materials and methods

Materials

Calcium caseinate was obtained as a gift from Chaitanya Biological Pvt. Ltd., Buldana, India and sodium alginate was obtained from Alpha Chemika, Mumbai, India. Refined rice bran oil, with oryzanol content of 1.35 % was obtained from Sethia Oils Ltd., India. Emulsions were prepared with de-ionised water. All other reagents were of analytical grade and procured from Merck India Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Methods

Emulsion preparation

Rice bran oil with a fatty acid composition of 12:0 (0.5 %), 14:0 (0.1 %), 16:0 (19.75 %), 16:1 (2.90 %), 18:0 (1.13 %), 18:1 (40.56 %), 18:2 (29.16 %), 18:3 (ALA) (3.45 %), 20:0 (1.35 %), 22:0 (1.10 %), was chosen as the core material.

Five different oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion formulations were prepared. The emulsions for this study were prepared according to a basic composition of 1.0 % (w/w) oil and 2.0 % (w/w) total solids. The oil and solid compositions were optimized after repeated experiments. The total solids comprise the emulsifier protein (calcium caseinate) and the encapsulant (sodium alginate) mixed in water or the dispersion media. The emulsions were formulated with five different protein contents, all expressed in proportion to the oil content (Table 1). Oil:protein ratios around 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 25:1 and 30:1 were explored. Measured quantities of CaCaS were mixed with 10 ml of buffer (pH 7), added gradually while continuously shaking for 24 h at 40 °C at a stirring rate of 600 rpm. Next day measured quantities of NaAlg were gradually added to the solution while adding the remaining amount of buffer (up to 100 ml) simultaneously, after bringing it to room temperature. Thereby it was homogenized (Remi Motors Homogenizer, Type: RQ-127A, Mumbai, India) at 2,000 rpm. Gradually 10 g core material (rice bran oil) was added to each of the solutions with constant stirring to generate the oil-in-water emulsions. pH was maintained at 7 throughout with phosphate buffer. The entire mixture was homogenized for 6 h at 2,000 rpm. After development of the emulsions (primary emulsions) they were washed with hexane to remove any un-emulsified lipid from the system. The procedure was repeated three times.

Table 1.

Emulsion formulations used for the preliminary study (All emulsions were given in weight basis, based on a 1,000 g emulsion)

| Ingredients (g) | Oil: Protein | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30:1 | 25:1 | 20:1 | 15:1 | 10:1 | |

| Calcium caseinate, CaCaS (emulsifier) | 0.32 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Sodium alginate, NaAlg (encapsulant) | 19.68 | 19.6 | 19.5 | 19.4 | 19.0 |

| Rice bran oil (Core material) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Water | 970 | 970 | 970 | 970 | 970 |

| Total (CaCas+NaAlg+Oil+Water) | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

Size-reduction

Size-reduction of the emulsions were achieved by ultrasonication (Ultrasonicator, Vibronics, 3172 Meco-G) for 1 h (carried out intermittently) at 200 V for all the emulsions, while maintaining a temperature of 10 °C throughout by carrying out the entire procedure on an ice bath.

Preparation of treated emulsions:alterations due to environmental stresses

The primary emulsion was subjected to stress generated by three different parameters, namely pH, temperature, and salt concentration. These parameters were optimized to develop the particular emulsion formulation which showed the best results at the different stressed parameters.

Stress due to pH alterations

The emulsions were treated with either acid or alkali to get a final pH of 5, 9 and 11. From each of the five emulsions, 30 ml was taken in test tubes. Their pH was adjusted to 5, 9 or 11 using HCl and/or NaOH solutions. The samples were shaken well and stored overnight at 10 °C before being further analyzed. The electrolyte concentrations of these emulsions were nil.

Thermal stress

A fresh set of emulsions were treated to temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C, and 70 °C. Once again 30 ml of each of the five emulsions were placed in a preheated water bath for 30 min at temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C and 70 °C. After 30 min, the test tubes were cooled and kept overnight at 10 °C before being further treated. The electrolyte concentrations of these emulsions were nil and their pH maintained at 7 with suitable buffer.

Salt stress

A third set of primary emulsions were treated with an electrolyte (sodium chloride) to formulate the final electrolyte concentration of the emulsions as 10 mM, 50 mM and 100 mM strengths. 30 ml of each emulsion was taken in test tubes and calculated amounts of sodium chloride were added to obtain the final concentrations of 10 mM, 50 mM and 100 mM. The treated emulsions were vortexed and stored overnight at 10 °C before further treatment. pH of these emulsions were maintained at 7 with suitable buffer.

Estimation of core material lipid content

Lipid was extracted from 1 g of each of the solvent washed emulsions after hydrolyzing the emulsions with acid (1 N HCl). The released core material lipid content was evaluated by extracting the fat with hexane. The emulsions were solvent washed prior to hydrolyzing to remove any un-emulsified oil from the system. Hence the amount of fat collected by hexane after hydrolysis of the emulsions was the amount encapsulated. The hexane layer was evaporated to dryness and the amount of fat emulsified was estimated. The process was repeated three times.

Core material composition of the emulsions

The fat extracted from the different emulsion formulations were converted into methyl esters (Ichihara et al. 1996) and analyzed by gas chromatography (AGILENT; Model: 6,890 N; FID detector; DB Wax column) to estimate the fatty acid composition of the encapsulated fat. The major fatty acid compositions were compared with the fatty acid composition of the oil.

Observation under transmission electron microscope

Qualitative characterization of the state of dispersion and extent of deviation of the emulsion morphology, when treated under various stresses is critical in developing processing parameters for a stable emulsion. The nano dispersions were studied using image analysis of 2D transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In order to perform TEM observations, a drop of the emulsions were directly deposited on carbon-coated grids, air-dried and observed under transmission electron microscope (FEI, Tecnai 20, Netherlands) at a resolution of 0.24 nm and accelerated voltage of 200 kV. The emulsion droplets appear dark and the surroundings are bright that is, a positive image is seen. The graphs display the distribution pattern of the emulsion droplets.

Estimation of particle-size

The particle size distribution and mean droplet diameter of the emulsions were measured using dynamic light scattering technique (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). Mean particle diameters were reported as Z-average diameters or the scattering intensity-weighted mean diameter. The particle size distributions of the emulsions were studied as a function of increasing emulsifier concentration. Samples were diluted prior to making the particle size measurements to avoid multiple scattering effects, using a dilution factor of 1:10 sample-to-deionised water. Data reported is a mean of 3 consecutive readings.

Stability of the emulsions

The electrical charges (ζ-potential) of the particles were determined using electrophoretic mobility measurements on diluted emulsion samples (Zetasizer Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK, Version: 4.20). Emulsions were placed in clear disposable zeta cells and loaded into the instrument. Samples were equilibrated for 60 s inside the instrument before the data were collected over at least 3 sequential readings. ζ-potential depends on the interfacial composition and structure and on the composition of the aqueous phase. Hence measurement of ζ-potential helps us to assess the stability of the emulsions.

Study of emulsion viscosity

Emulsion viscosities were observed using Brookfield viscometer (DV-II + Pro Viscometer, Brookfield, Brookfield Engineering Labs. Inc. Middleboro, USA) at 100 rpm with S21 spindle at a temperature of 25 °C. The viscosity of the emulsions was studied as a function of increasing emulsifier concentrations. The study would help to understand the mechanism of interactions among protein, lipid and sodium alginate under different temperature, pH and electrolytic conditions and hence facilitate formulations of food emulsions with desirable texture and appearance.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA detected significant differences between mean values, means were compared using Tukey’s test. For statistical studies OriginLab software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, UK) was used. Statistical significance was designated as P < 0.05. Values are expressed as Mean ± SEM.

Results

Encapsulation efficiency

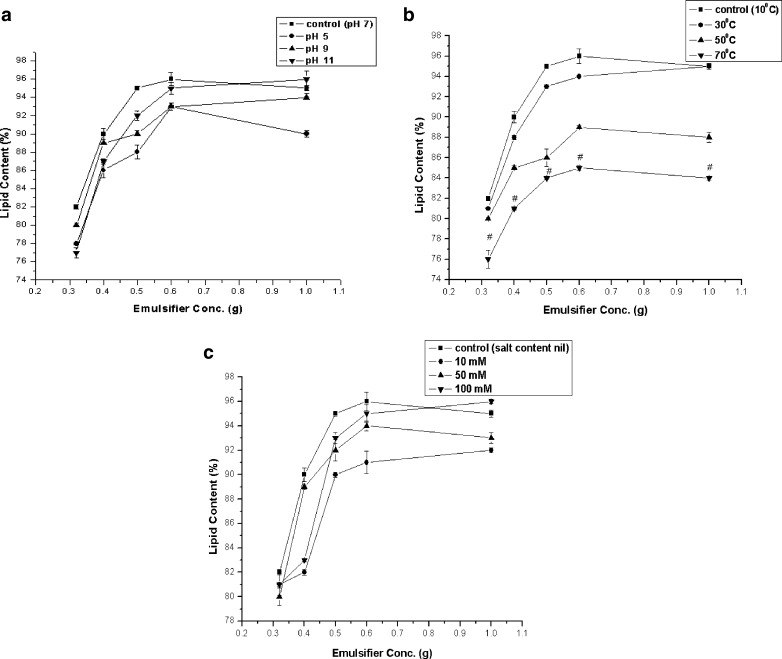

Efficiency of encapsulation of the five different primary emulsions is presented in Table 2. In case of all the emulsions 1.0 g of oil was initially emulsified with water. On lipid extraction from prior solvent-washed emulsions it was observed that 0.96 g of oil was encapsulated for 10:1 emulsion and 15:1 emulsions. For 20:1 emulsion 0.95 g, for 25:1 emulsion 0.90 g and for 30:1 emulsion 0.82 g lipid was encapsulated. Hence maximum efficiency of encapsulation (96 %) was achieved in the case of 10:1 and 15:1 emulsions. To ensure that the oil estimated was the encapsulated lipid, the un-encapsulated oil was removed by an initial solvent (hexane) wash of the emulsions before extracting the lipid. Retention of lipid content was lower for emulsions treated under different environmental stresses as observed from the plot of Fig. 1. pH study (Fig. 1a), temperature study (Fig. 1b) and electrolyte study (Fig. 1c) show the variation of different parameters with the lipid content of the emulsions.

Table 2.

Encapsulation efficiencies of the five emulsion formulations

| Emulsions (oil: protein) | Initial Amount of oil takena (g) | Final amount of oil obtainedb (g) | Encapsulation efficiencyc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10:1 | 1.0 ± 5.773 × 10−2 | 0.96 ± 6.225 × 10−3 | 96 ± 0.103 |

| 15:1 | 1.0 ± 4.819 × 10−2 | 0.96 ± 5.934 × 10−3 | 96 ± 0.120 |

| 20:1 | 1.0 ± 3.652 × 10−2 | 0.95 ± 1.108 × 10−3 | 95 ± 0.025 |

| 25:1 | 1.0 ± 2.964 × 10−2 | 0.90 ± 8.300 × 10−3 | 90 ± 0.267 |

| 30:1 | 1.0 ± 6.317 × 10−2 | 0.82 ± 7.256 × 10−3 | 82 ± 0.117 |

a,b,cValues are expressed as mean ± S.E.M, n = 3

Fig. 1.

Variation of Lipid Content with emulsifier concentration at different (a) pH, (b) temperature and (c) electrolyte concentrations. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (b), # p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

Fatty acid composition of the emulsions

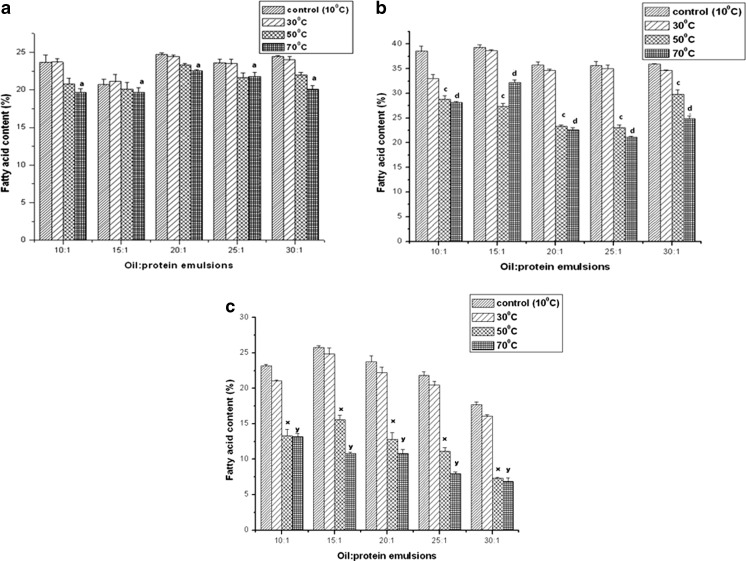

Rice bran oil, used as the core material, is primarily oleic-linoleic acid based oil. The fatty acid compositions of the primary emulsions are tabulated in Table 3. The three major fatty acids present are palmitic acid (16:0), oleic acid (18:1) and linoleic acid (18:2). Figure 2a demonstrates the variation of palmitic acid content of emulsified lipids on treatment with acid/alkali. It is found to significantly differ from the control variety. However the change for palmitic acid is less as compared to oleic (Fig. 2b) and linoleic (Fig. 2c) acids, of which linoleic acid degraded rapidly at pH 5. Again for saturates (palmitic acid) (Fig. 3a), noticeable difference is detected only at very high temperatures like 70 °C. However for unsaturates (oleic and linoleic acid) the deterioration occurs rapidly at temperatures of 50 °C and above (Fig. 3b and c). Electrolyte treatment did not show significant change in lipid composition of the emulsions. Palmitic acid (Fig. 4a) content remained almost unaltered at all emulsifier concentrations with slightly higher values at 50 mM and 100 mM salt concentrations. For oleic (Fig. 4b) and linoleic (Fig. 4c) acids however, a high quantity of fatty acid was observed at 50 mM and 100 mM electrolyte concentrations, especially for 30:1 system.

Table 3.

Fatty acid profile of the five emulsion formulations before stress treatment

| Fatty acids (%wt) → | Fatty acidsd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emulsions (oil: protein) ↓ | 12:0 | 14:0 | 16:0 | 16:1 | 18:0 | 18:1 | 18:2 | 18:3 (ALA) | 20:0 | 22:0 |

| 10:1 | 1.74 ± 0.82 | 0.50 ± 0.23 | 22.69 ± 1.84. | 3.88 ± 0.95 | 2.85 ± 0.44 | 38.63 ± 1.08 | 23.20 ± 0.73 | 2.69 ± 0.91 | 1.97 ± 0.67 | 1.85 ± 0.85 |

| 15:1 | 1.59 ± 0.48 | 0.81 ± 0.99 | 20.68 ± 1.67 | 2.55 ± 0.70 | 2.54 ± 0.86 | 39.30 ± 2.05 | 25.78 ± 1.85 | 3.04 ± 0.97 | 1.80 ± 0.75 | 1.91 ± 0.59 |

| 20:1 | 2.05 ± 0.64 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 24.71 ± 1.22 | 3.04 ± 0.96 | 2.03 ± 0.36 | 35.72 ± 0.82 | 23.73 ± 1.81 | 2.71 ± 0.24 | 2.24 ± 0.36 | 2.91 ± 0.71 |

| 25:1 | 2.37 ± 0.55 | 1.07 ± 0.63 | 23.62 ± 1.54 | 2.45 ± 0.28 | 2.97 ± 0.46 | 35.69 ± 2.69 | 21.82 ± 1.59 | 2.61 ± 0.73 | 3.73 ± 0.06 | 3.67 ± 0.66 |

| 30:1 | 3.31 ± 0.56 | 2.71 ± 0.81 | 24.46 ± 1.17 | 2.86 ± 0.53 | 3.14 ± 0.69 | 35.91 ± 2.05 | 17.69 ± 1.03 | 1.41 ± 0.33 | 4.65 ± 0.64 | 3.86 ± 0.27 |

dValues are expressed as mean ± S.E.M, n = 3

Fig. 2.

Variation of Fatty Acid Content for different emulsion systems at three pH systems. Fatty acid content for palmitic (16:0), oleic (18:1) and linoleic (18:2) acids are reported at altered pH values, (a) variation of 16:0 content at different pH, (b) variation of 18:1 content at different pH and (c) variation of 18:2 at different pH. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (a), a p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5. Figure (b), b p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5. Figure (c), o p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

Fig. 3.

Variation of Fatty Acid Content for different emulsion systems at three temperatures. Fatty acid content for palmitic (16:0), oleic (18:1) and linoleic (18:2) acids are reported at altered temperatures, (a) variation of 16:0 content at different temperatures, (b) variation of 18:1 content at different temperatures and (c) variation of 18:2 at different temperatures. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (a), a p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Figure (b), c p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 50 °C, d p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Fig. (c), x p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 50 °C, y p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

Fig. 4.

Variation of Fatty Acid Content for different emulsion systems at three salt concentrations. Fatty acid content for palmitic (16:0), oleic (18:1) and linoleic (18:2) acids are reported at altered salt concentrations, (a) variation of 16:0 content at different salt concentration, (b) variation of 18:1 content at different salt concentraton and (c) variation of 18:2 at different salt concentrations. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations

Study of emulsion morphology

The distribution of emulsion droplets was studied using transmission electron microscope. Morphology of a primary emulsion (15:1 emulsion system) was compared with its corresponding treated emulsion. A high particle density was observed for the primary emulsion (Fig. 5a). However the appearance of agglomerates was detected in some places. When treated with acid (Fig. 5b) droplets have displayed a tendency to coagulate due to the instability of protein emulsifier in an acidic medium. Electrolyte treated emulsions with 100 mM concentration (Fig. 5c) showed a uniform, stable and homogeneous morphology. Hence addition of an electrolyte to an aqueous suspension medium during the development of an oil-in-water emulsion is a major contributing factor for obtaining a long term stable emulsion. In contrary, on subjecting the emulsions at a temperature of 50 °C (Fig. 5d), coalescence of droplets was observed. When a single droplet is observed closely under the microscope (Fig. 5e), a uniformly round, opaque droplet was observed.

Fig. 5.

TEM micrographs of dispersed emulsion droplets. a Distribution pattern of emulsion droplets in 15:1 emulsion system (primary emulsion) at a magnification of 2,100. b Distribution pattern of emulsion droplets of 15:1 emulsion system, when treated with acid to a pH of 5 at a magnification of 2,100. c Emulsion droplet distribution of 15:1 system when treated with NaCl at 100 mM concentration at a magnification of 5,000. d Droplet distribution pattern for 15:1 emulsion system when treated at 50 °C at a magnification of 2,550. e A closer view of a single droplet of the 15:1 emulsion system when magnified 9,900 times by selected area electron diffraction (SAED)

Variation of particle-size

When the emulsions were treated at different pH, particle-size was found to vary significantly (Fig. 6a) especially for emulsions treated at an acidic pH. Alkaline treatment of emulsions showed a droplet-size trend similar to that of the primary emulsion (the ‘control’). For emulsions with pH of 5 or below, rapid de-emulsification occurred. Temperature treatments revealed that at 50 °C and 70 °C (Fig. 6b) significant increase in particle size was observed. On the contrary at 30 °C negligible change in particle-size was observed. Furthermore, particle-size did not significantly vary with electrolyte treatments (Fig. 6c). Low particle-size was observed for emulsions with 100 mM electrolyte concentration than that for 10 mM and 50 mM concentrations.

Fig. 6.

Variation of particle-size with emulsifier concentration at different (a) pH, (b) temperature and (c) electrolyte concentrations. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (a), x p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5. Figure (b), y p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 50 °C, z p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

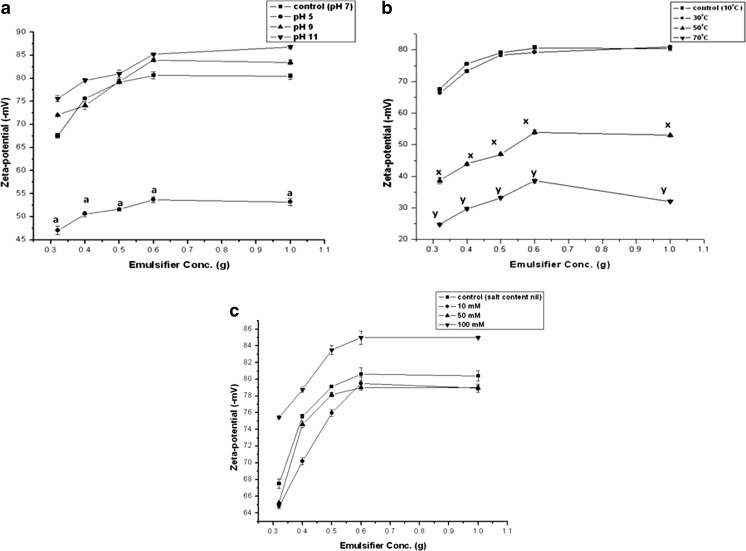

Variation of zeta-potential

With increasing sonication time the size of the emulsion droplets decreased. After a certain time, on approaching an optimum condition (in this case after one hour of sonication), the emulsion droplets showed no further size lowering. Such emulsions were found to be more stable over a longer period of time (Jafari et al. 2006). Ultrasonication results in nano-sized droplets and smaller the droplet size more thermodynamically stabilized emulsions are formed (Folch et al. 1957). Zeta-potential was found to significantly vary with increasing emulsifier concentration at pH 5 (Fig. 7a). Greater emulsifier concentration ensures greater emulsion stability. Low emulsion stability was observed at high temperatures (Fig. 7b). Again in presence of sodium chloride highest emulsion stability was achieved when 100 mM salt concentration was maintained (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Variation of zeta-potential with emulsifier concentration at different (a) pH, (b) temperature and (c) electrolyte concentrations. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (a), a p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5. Figure (b), x p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 50 °C, y p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

Variation of viscosity

Rheological changes of the emulsions with increasing emulsifier concentrations were studied. At low emulsifier concentration high viscosity was observed, which gradually decreased on increasing the emulsifier concentration and finally reached an almost steady value. Thus at low emulsifier concentrations and low pH values the emulsions became unstable (Fig. 8a). As temperature increased viscosity of the emulsions decreased (Fig. 8b). Moreover electrolyte concentrations of emulsions were found to influence viscosity of the system profusely (Fig. 8c). Viscosity decreased with successive addition of electrolyte to the emulsion.

Fig. 8.

Variation of viscosity with emulsifier concentration at different (a) pH, (b) temperature and (c) electrolyte concentrations. Values are Mean ± S.E.M of 3 observations. Figure (a), a p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 5, b p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 9, c p < 0.05, control (pH 7) vs. pH 11. Figure (b), x p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 50 °C, y p < 0.05, control (10 °C) vs. 70 °C. Figure (c), d p < 0.05, control vs. 10 mM, e p < 0.05, control vs. 50 mM, f p < 0.05, control vs. 100 mM. Means were compared using Tukey’s test

Discussion

Encapsulation efficiency indicates the amount of oil that is retained in the inner core after the completion of the entire process of encapsulation. Sufficient interfacial properties must be introduced during the synthesis of an emulsion in order to stabilize it. Formation of a homogeneous emulsion is essential in the encapsulation of the core material. Sodium alginates are considered as good encapsulants because of their high solubility, heat resistance and anti-breaking properties and will lead to the formation of a homogeneous emulsion. However a homogeneous emulsion is stable only when a proper emulsifier is added to it during its preparation. Here concentration of calcium caseinate was varied according to the different oil:emulsifier ratios. The purpose was to explore the emulsion properties for varying emulsifier contents in respect of emulsion droplet sizes and structural stability. The emulsion with the smallest particle-size, highest stability and maximum retention of core material compositions, was the desired one. Concentration of the emulsifier proved to be important in the stabilization of emulsions. Calcium caseinate acts as an efficient emulsifier at high or intermediate concentrations (10:1 and 15:1). Low emulsifier concentrations are not enough to bring the lipid core material into the solution, resulting in lower encapsulation efficiencies. The core material shows increased solubilization with increasing emulsifier concentration leading to higher encapsulation efficiencies. Oxidation of the core material lipid affects lipid quality leading to lower lipid contents as detected. In case of pH study (Fig. 1a), lipid content was least for acid treated emulsions (at pH 5). In fact it was observed that maximum retention of lipid was at alkaline pH and almost comparable results were observed at pH 9 and 11. At acidic pH alginate gets swollen resulting in easy diffusion of acidic medium and that in turn protonates the caseinate leading to its precipitation. This leads to weaker oil-holding capacity. The reverse is true at high pH values. Small amounts of calcium will greatly increase the stability of sodium alginate solutions (McNeely and Pettitt 1973). Moreover alginates are most stable in the range of alkaline pH (McDowell 1961), leading to high stable emulsions at higher pH values. Similarly in case of temperature variations (Fig. 1b), at 70 °C significant level of difference in lipid content was observed. At 50 °C too enough oil loss has occurred. However lipid content was almost unchanged at 30 °C from that observed at 10 °C in the case of primary emulsions. Temperature increase generally causes a decrease in the effectiveness of adsorption of protein emulsifiers. Hence a significant difference was observed at 70 °C due to weak emulsifier binding at such a high temperature. Moreover de-polymerization occurs when alginates are preserved at high temperatures (>50 °C) for some time, in turn affecting the inner core material. However for electrolyte treated emulsions (Fig. 1c), maximum retention of lipid was observed for emulsions treated with highest amount of electrolyte. At lower electrolyte contents, occurrence of oxidation was observed. An increase in the ionic strength of the aqueous phase due to the addition of neutral electrolyte, NaCl, probably caused decreased attraction between oppositely charged species and the decreased repulsion between similarly charged species at higher ionic strength resulting in higher efficiencies.

Again fatty acid composition analysis showed lowest retention of essential fatty acids when the emulsions are stress-treated at an acidic pH (Fig. 2). This is possibly due to the deterioration of the protein emulsifier on interaction with acid leading to a poor oil-in-water stability, as discussed before. On temperature treatment, a significant change in fatty acid composition is observed at high temperatures. The deterioration of the oil quality was most eminent for emulsions with low emulsifier content (Fig. 3). 10:1 and 15:1 emulsions give the best results in terms of core material protection. However 15:1 formulation shows better thermal stability in comparison to 10:1. Again high electrolyte concentrations retard oxidative rancidity, caused due to hydrolysis in the presence of water (Fig. 4). Hence retention of both saturates and unsaturates occur to a considerable degree at high electrolyte concentrations. In fact for the emulsion with the lowest emulsifier concentration the presence of electrolyte had a redeeming effect on the retention of the most unsaturated fatty acids like linoleic acid.

It is well known that, emulsion stability with respect to creaming and coalescence depends on the droplet-size distribution, the state of aggregation of the droplets and the rheology of the aqueous dispersion medium. The droplet-size distribution is mainly determined by the energy input during emulsification (Chandra shekhar et al. 2011). Particle-size of the emulsions shows a definite pattern when plotted against emulsifier concentrations. At low emulsifier concentration a large particle-size is observed. With increasing emulsifier concentration particle-size gradually decreases, reaching a steady value at high emulsifier concentrations. Ultrasonication serves as an effective means of de-agglomerating and dispersing needed to overcome the bonding forces after wettening the encapsulant/emulsifier, in this case sodium alginate/calcium caseinate. Once the liquids are exposed to ultrasound, the sound waves that propagate into the liquid generate ultrasonic cavitations which results in alternating high-pressure and low-pressure cycles. This applies mechanical stress on the attracting forces between individual particles, thus reducing Van der Waals forces in the agglomerates. At a constant energy density, stabilizers/emulsifiers play an important role in promoting improved droplet dispersion (Maa and Hsu 1999). Higher the energy density, smaller is the droplet size achieved. However extreme homogenization conditions like continuous 1 h sonication treatment can lead to the development of oxidized products and denaturation of the emulsifier protein. Hence the entire reaction was carried out at a low temperature of 10 °C by using an ice bath. Moreover sonication was applied intermittently at 10 min interval and not continuously for 1 h to prevent the increase of system temperature. Below pH 7, the hydrodynamic diameters of the particles increased drastically (Fig. 6a). This can be attributed to the swelling of sodium alginate in acidic medium. The sodium alginate particles became protonated on addition of acid, leading to larger sized particles due to flocculation as explained previously (Fig. 5b). Emulsifiers adsorb at the oil/water interface and form a protective film around the dispersed oil droplets, preventing them from coalescence, thus leading to an enhanced stability of the emulsion. On lowering the pH, the protein emulsifier at the interface was affected and degraded leading to flocculation of the droplets, responsible for the higher particle-size data. Since the effective size of emulsion droplets depend on the coalescence rate, higher the creaming velocity, greater was the size of the particles. At lower concentrations of the protein emulsifier emulsions were further more affected by low pH treatment than the ones with high emulsifier concentrations. Hence high protein emulsifier led to low particle-sized emulsions and vice versa. Again at a high temperature uniform consistency of the emulsions changed due to protein denaturation and profuse agglomeration leading to higher droplet-size (Fig. 6b). The thermal instability of alginates may be attributed to the linear anionic molecules with no branches which contribute to steric, electrostatic or thermal stabilization. Alginate binds to the caseinate emulsifier by forming combination gels through the Ca2+ ions of caseinates, thus giving birth to a type of chemically set gels (Reis et al. 2005). Moreover the larger concentrations of sodium chloride (100 mM) brought about solubilization of the caseinate in a nonmicellar form. The CaCaS-alginate gel system became de-swollen in the presence of an electrolyte as increase in ionic strength decreased the Debye screening length due to the reduction of the repulsive electrostatic forces between similar charged groups, in this case the negatively charged colloidal calcium caseinate groups (Schokker and Dalgleish 2000). The charge helped to maintain calcium caseinate as a physically stable colloid (Fig. 6c). At low sodium chloride concentration, the stabilizing repulsive effects between the negatively charged ions is lower leading to destabilization and certain degree of flocculation in consequence.

Now in emulsions, which are electrostatically stabilized, zeta provides a measure of the electrical repulsive force between particles. Hence it can be used for monitoring and controlling emulsion stability. The increase in energy of an emulsion system is the cause for thermodynamic instability of the system. Increased energy of the system thus leads to coalescence, which must be minimized in order to generate a stable emulsion. At alkaline pH slightly better stability was observed than that at neutral pH (Fig. 7a). Calcium caseinate has a tendency to remain anionic at high pH and cationic at low pH due to protonation of the caseinate group (Post et al. 2012). The stability of the emulsion can be attributed to the electrostatic binding between the emulsifier and the water soluble encapsulant. The isoelectric point of the protein is about 4.6. Hence the emulsifier remains anionic at high pH, but become cationic at low pH, due to protonation of the caseinate group. At lower pH values, emulsifier protein denatures and hence precipitation occurs due to the increased intermolecular association. The net effect of these interactions is the lowered stability of emulsions at pH 5 or below. Denaturation of caseinate occurs at high temperatures resulting in increased flocculation (Fig. 7b). As the emulsifier network breaks down, the mobility of the core material lipid increases, resulting in destabilization of the emulsion. Again lower the emulsion particle-size higher is the stability. As explained before, by maintaining a moderately high electrolyte concentration of about 100 mM, long-term stable emulsions can be achieved without coalescence (Fig. 7c).

In the present work as the net solid content was kept constant, at low emulsifier concentrations, sodium alginate concentrations were high. High molecular weight alginate particles show non-Newtonian behavior (pseudoplasticity) when used at an increased concentration. Hence stable emulsions with a pH range of 6–8 recorded an intermediate viscosity (Fig. 8a). Electrostatic repulsion at high concentrations of caseinate were found to disrupt the gel network indicating that structure of a protein plays a vital role in stabilizing an emulsion (Cristián et al. 2012), reflected by its viscosity behaviour. Furthermore emulsions heated to 70 °C showed a visco-elastic behavior. This resulted in a low viscosity value at temperatures up to 70 °C, beyond which rapid flocculation and increased viscosity was observed (Fig. 8b). Viscosity is a temperature dependant process, giving lower values at high temperature and vice versa. At neutral pH, turbidity increased when sodium caseinate emulsions were heated in situ at temperatures above a critical temperature due to considerable hydrophobic interactions it encountered (Singh et al. 2012). Finally the existence of electrolytes in the aqueous media enhances the thermal efficiency of the emulsions. Presence of sodium chloride also modifies the interfacial properties of the emulsion. The interaction of water with the polar interfacial film probably gets stronger as an electrolyte is added to the system. Due to this the viscosity of the system with high electrolyte content is significantly low (Fig. 8c). For similar reasons, the viscosity of the emulsions at 50 mM concentration is lower than that of the primary emulsions. Thus based on these results the individual parameters which contribute to the development and preservation of a nanoemulsion were optimized. In other words, the emulsification conditions with respect to temperature, pH and electrolyte concentrations which are suitable for the development of a stable nanoemulsion were formulated. Hence alkaline pH, temperatures up to 50 °C and high electrolyte concentrations of about 100 mM were the optimized values.

Conclusion

In this work an experimental study was conducted to prepare a stable nanoemulsion containing a soluble encapsulant using a protein emulsifier. The effects of a set of operating variables like temperature, pH and added electrolytes on the retention of the stability and particle-size of emulsions were evaluated. Based on the obtained set of parameters that affect the stability of the nanoemulsion a system was optimized for the development of the most stable nanoemulsion. A stable nanoemulsion containing an encapsulant could be prepared using quite low proportions of the protein emulsifier caseinate. By estimation of particle-size and zeta-potential, it was deciphered that a stable oil-in-water emulsion can be fabricated by maintaining the oil:protein ratio of 10:1 or 15:1, as these emulsions displayed most promising results. However, 15:1 emulsion system is preferable to 10:1 system due to lower emulsifier requirements and better thermal stability. The optimized parameters are: process temperature - within 50 °C, pH - neutral or alkaline and electrolyte concentration - up to 100 mM of neutral electrolyte concentration is admissible for retaining long-term stable emulsions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the ‘Council of Scientific and Industrial Research’ (CSIR) for their financial support. Sincere acknowledgements are also due for M/S Chaitanya Biological Pvt. Ltd., Buldana, India for their help in supplying food grade calcium caseinate and the DLS facilities obtained at Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute (CGCRI), Jadavpur, West Bengal, India for particle-size and zeta-potential analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

- CaCaS

Calcium caseinate

- NaAlg

Sodium alginate

References

- Aftabrouchard D, Dorlker E. Preparation methods for biodegradable microparticles loaded with water-soluble drugs. STP Pharma Sci. 1999;2:365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchemal K, Briancon S, Perrier E, Fessi H. Nano-emulsion formulation using spontaneous emulsification: solvent, oil and surfactant optimization. Int J Pharm. 2004;280:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Salou C, Cheftel JC. Emulsifying salts influence on characteristics of cheese analogs from calcium caseinate. J Food Sci. 1991;56:1542–1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb08636.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Shekhar M, Bahuguna Chary B, Srinivas S, Kumar BR, Mahendrakar MD, Varma MVK. Effect of ultrasonication on stability of oil in water emulsions. Int J Drug Deliv. 2011;3:133–140. doi: 10.5138/ijdd.2010.0975.0215.03063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cristián HI, Víctor M, Pizones RH, Roberto J, Candal M, Herrera L. Effect of aqueous phase composition on stability of sodium caseinate/sunflower oil emulsions. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb DN, Ford LR, Martin RW. Food emulsions. In: Larsson K, Friberd SE, editors. Dressings and sauces. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1990. pp. 287–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara K, Shibahara A, Yamamoto K, Nakayama T. An improved method for rapid analysis of the fatty acids of glycerolipids. Lipids. 1996;31:535–539. doi: 10.1007/BF02522648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari SM, He Y, Bhandari B. Nano-emulsion production by sonication and microfluidization–a comparison. Int J Food Prop. 2006;9:475–485. doi: 10.1080/10942910600596464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maa YF, Hsu CC. Performance of sonication and microfluidization for liquid-liquid emulsification. Pharm Dev Technol. 1999;4:233–240. doi: 10.1081/PDT-100101357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClements DJ. Nanoemulsions versus microemulsions: terminology, differences, and similarities. Soft Matter. 2012;8:1719–1729. doi: 10.1039/C2SM06903B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell RH (1961) Properties of alginates. In: Alginate Industries Ltd. (London) pp. 67–77

- McNeely WH, Pettitt DJ. Alginates. In: Whistler RL, editor. Industrial gums. New York: Academic; 1973. pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Milane LJ, Vlerken LV, Devalapally H, Shenoy D, Komareddy S, Bhavsar M, Amiji M. Multi-functional nanocarriers for targeted delivery of drugs and genes. J Control Release. 2008;130:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post AE, Arnold B, Weiss J, Hinrichs J. Effect of temperature and pH on the solubility of caseins: environmental influences on the dissociation of αS- and β-casein. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:1603–1616. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford SJ, Dickinson E, Golding M. Stability and rheology of emulsions containing sodium caseinate: combined effects of ionic calcium and alcohol. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;274:673–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis CP, Neufeld RJ, Ribeiro AJ, Viega F (2005) Insulin-alginate nanospheres: influence of calcium on polymer matrix properties. Proceedings of the 13th international workshop on Bioencapsulation: Kingston, Ontario, Canada, Queen’s University

- Sanguansri P, Augustin MA. Nanoscale materials development – a food industry perspective. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2006.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schokker EP, Dalgleish DG. Orthokinetic flocculation of caseinate-stabilized emulsions: influence of calcium concentration, shear rate and protein content. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:198–203. doi: 10.1021/jf9904113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu XZ, Zhu KJ. The release behaviour of brilliant blue from calcium-alginate gel beads coated by chitosan: The preparation method effect. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;53:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(01)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SS, Edwards PR, Ye H. Temperature-dependant complexation between sodium caseinate and gum Arabic. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;26:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M, Singh H, Munro PA. Adsorption behaviour of sodium and calcium caseinates in oil-in-water emulsions. Int Dairy J. 1999;9:337–341. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(99)00084-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]