Abstract

The formation oxytetracycline (OTC) degradation products in chicken and pork under two different methods of cooking were studied. Samples of chicken and pig muscles previously dosed with OTC residues were subjected to boiling or microwave treatment, and the residues were extracted in a mixture of citrate buffer-MeOH (75:25 v/v), and then analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography with photodiode array detection using a XBridgeTM C18 reverse-phase chromatographic column. Thermal treatment resulted in the degradation of OTC and the concentrations of the degradation products α-apo-oxytetracycline (α-apo-OTC) and β-apo-oxytetracycline (β-apo-OTC) in muscle samples amounted to 0.7 to 1.2 % of the initial OTC content. The toxic effects of the degradation products of oxytetracycline, α-apo-OTC and β-apo-OTC were studied in rats. Male rats received oral doses of 10 mg/kg body weight/day of either α-apo-OTC, β-apo-OTC, 90 days. The results of this study suggest that the toxic effects of β-apo-OTC treatment could damage liver and kidney tissues of rats, as well as lead to the degeneration and necrosis in the hepatocytes.

Keywords: Oxytetracycline, Thermal degradation, Meat, HPLC, Toxic effect, Rats

Introduction

Oxytetracycline, is a member of the tetracycline (TC) family of antibiotics, and its therapeutic use has been of particular interest for use in food producing animals because of its broad spectrum activity and its low cost. OTC has been widely used for preventing and controlling diseases, and also as a feed additive to promote the live-weight gain. However, excessive and improper use of OTC results in accumulation in edible animal tissues, which may be toxic and dangerous for human health, as well as cause allergic reactions. Moreover, the long-term presence of OTC residues in tissues may lead to antibiotic resistance in the animals (Chopra and Roperts 2001; Garcia et al. 2004). Usually these edible tissues are cooked before consumption, however it is not known whether oxytetracycline, or any degradation products, remain in the food and therefore pose a threat to human health. It is essential that the effect of cooking, and the cooking process, be investigated to determine the likelihood of a consumer being exposure to OTC and any breakdown products. Several studies have demonstrated the rapid formation of anhydrous derivatives of TC in chicken and pig bones following high-temperature and strongly-acidic treatments (Kuhne et al. 2001a, b). Degradation products of TC have been shown to be related to Fanconi-type syndrome, a reversible renal dysfunction (Frimpter et al. 1963). Others (Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007) have indicated that relatively mild thermal processes, similar to those applied to meat during household cooking, may initiate the thermal breakdown of TC with the formation of anhydrotetracycline (ATC), 4-epi-anhydrotetracycline and two unidentified degradation products. Thermal treatments with food additive combinations were found to have significant effects on the rate of OTC degradation (Fedeniuk et al. 1997). Products of heat-degraded OTC have also been shown to exhibit toxic effects, though the products have not been identified (Tropiło et al. 1988). Halling-Sorensen et al. 2002 reported that the degradation products of OTC, such as 4-epi-oxytetracycline (EOTC), α-Apo-OTC and β-Apo-OTC exhibited greater toxicity (EC50) compared with the parent compound. Several studies indicate that thermal treatments reduce the concentration of various veterinary drug residues in foods and thus decrease the potential toxic effects of these compounds on the consumer (Furusawa and Hanabusa 2001; Javadi 2011; O’Brien et al. 1981; Rose et al. 1996; Kuhne et al. 2001a, b; Lolo et al. 2006). However, in these studies only the degradation of the parent drug was evaluated and the toxic effects of the degradation products of the parent drug was not studied.

The objective of this study is to understand the occurrence and the degradation of OTC and their degradation products in chicken and pork following thermal treatment and determine the toxicity of oxytetracycline degradation products when they were orally administered to rats. The results should provide useful information for assessing the impacts or potential risks of antibiotics residues in meat on human health.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade purity. Acetonitrile and methanol were of HPLC grade (Merck Company, Germany). The standards of 4-epi-oxytetracycline, α-apo-oxytetracycline and β-apo-oxytetracycline were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Oxytetracycline hydrochloride was obtained from Merck (Calbiochem, Merck Company, Germany).

Equipment

An Agilent Technologies HPLC (Series 1200) (Waldbronn, Germany) was equipped with an online vacuum degasser (G1322A), a quaternary pump system (G1311A), an auto sampler (G1367A) and a photodiode-array detector (G1315B). The analytical column was a reverse-phase (XBridgeTM C18 250 mm × 4.6 mm I.D., 5 μm, Waters, Ireland). Water purification systems (Mul- 9000 series, USA) online GC 200 expansion vessel for potable water (Global water solution company, USA) and a nano pure Model 7150 (Thermo Scientific). For sample preparation ULTRA-TURRAX T25 Basic homogenizer (IKA works, Staufen, Germany), Centrifuge Allegra 64R (Beckman coulter, USA), Ultrasonic (KQ-300DE, Kun Shan, China). For cooking processes (C-MAG HP10) (IKA works, Staufen, Germany), Microwave oven (800 W, 2,450 MHz, Galanz, China) were used.

Standard solutions

Stock standard solutions of OTC, EOTC, α-AOTC, and β-AOTC were individually prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the compound in 10 mL of methanol with shaking in an ultrasonic bath for 4 min to obtain a final concentration of 1 mg mL−1. Stock standard solutions were then put in amber glass containers to prevent photo-degradation, and were stored at −20 °C. When required, they were diluted with methanol to give a series of working standard solutions. Finally, from stock solutions, a series of duplicate calibration standards were mixed in concentrations from 0.05 to 3 mg L−1. Chromatographic solutions for each compound were prepared by dilution of the combined working solution with mobile phase.

Meat sample preparation

Pork loin muscles were obtained from pigs produced on organic farms. Chicken breast muscle was also obtained from chickens raised on organic farms (free antibiotic chicken type). These samples were analyzed to ensure that no samples contained TC residues and then they were stored at −20 °C until use. A stock solution of OTC was prepared by dissolving 250 mg of pure standard in 10 mL methanol (final concentration = 25 g L−1). Antibiotic free pig and chicken muscles were individually homogenized in a bowl cutter (Model GM 200, Retsch, Germany) and then fortified with a methanolic stock solution of OTC. For this, 5 mL of the OTC methanolic stock solution (25 g L−1) was added to aliquots of 250 g of meat for each species thereby achieving a final concentration of 500 mg OTC kg−1 in the tissue (contaminated samples). They were immediately analyzed before any further treatment to verify the homogeneity of OTC addition in the samples. Once homogeneity had been confirmed, the mixtures were portioned into 10 g meat balls.

Thermal treatments

Boiling treatment

The meat balls were packed in aluminum bags. Each 10 g sample (meat ball) was first tempered to an initial temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and then immersed in a water bath (Jin Tan, Heng Fing, China) at 100 °C for 3, 6, or 15 min. The juice formed during the thermal treatment was collected.

Microwave treatment

The meat balls were packed in commercial food grade polypropylene trays. Each 10 g sample (meat ball) was tempered to an initial temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and placed at the geometric center of a turntable in a domestic microwave oven. Each sample was cooked under full power (800 W, 2,450 MHz) for 0.5, 1 or 2 min. The juice formed during the thermal treatment was collected.

After treatment, all samples were immediately placed in an ice bath, and stored at −20 °C for subsequent analysis within 1 day. All cooking treatments were done in triplicate.

HPLC analysis

Sample preparation procedure

The procedure used for the extraction of the OTC and its derivatives from the prepared samples was as previously described (Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007; Shalaby et al. 2011; MacNeil et al. 1996). Initially, four methods of extraction were evaluated: (i) McIlvaine buffer-EDTA; (ii) Citrate buffer; and (iii) McIlvaine buffer-EDTA/MeOH (75:25 v/v); (iv) Citrate buffer-MeOH (75:25 v/v). The procedure for the analysis of OTC and its derivatives from treated and untreated samples (whole quantity, 10 g) was done as follows. An aliquot of 10 g (accuracy, 0.01 g) of muscle sample was cut in small pieces and placed in a glass centrifuge tube. The juice formed during the thermal treatment was collected and added to the extract. 20 mL of the extraction solution was added and the sample was blended using a homogenizer for 3 min in ice. The homogenizer probes were then rinsed into the initial samples in centrifuge tubes with 3 mL extraction solution and then the tubes were vortexed for 1 min and sonicated for 10 min. This was followed by centrifugation at 12,100 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and the precipitate extracted again after adding 20 mL Citrate buffer-MeOH as described above. The combined supernatant were filtered through a filter paper and diluted to a final volume of 50 mL with extracting solution. One millilitre of the final extract was filtered through a nylon filter (porosity: 0.45 μm) and 100 μL was injected into the chromatographic system.

Linear range, limit of detection, limit of qualification and recovery

The analytical HPLC column was set at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The column was run at ambient temperature. Mobile phase A was acetonitrile, solvent B was methanol, while mobile phase C was 0.1 M phosphate-buffer pH 8. The starting mobile phase composition at 0 min was 7:8:85, methanol/acetonitrile/phosphate buffer at 1.0 mL min−1 (Table 1). The wavelength of the UV detector was set at 253 nm.

Table 1.

Gradient elution program

| Time (min) | Mobile phases % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Methanol | 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8.0 | |

| 0 | 7 | 8 | 85 |

| 3.5 | 7 | 8 | 85 |

| 5.5 | 10 | 20 | 70 |

| 25 | 10 | 20 | 70 |

| 25.1 | 7 | 8 | 85 |

| 30 | 7 | 8 | 85 |

Calibration curves were prepared daily by injecting chromatographic standard solutions in the range between 50 and 3,000 ng injected for each compound and estimates of the amount of the analytes in samples were interpolated from these graphs. LOD and LOQ were determined using the standard deviation of the response (σ) and the slope of the calibration curves (S) as follows equations (ICH Steering Committee 1996):

Sample recovery was determined with blank muscles spiked at 10, 20 and 30 μg g−1 for the raw samples (10 g). The spiked samples were analyzed and the recoveries calculated by comparing the peak area of measured concentration to the peak area of the spiked concentration.

Physicochemical and chemical analyses

Samples were analyzed for moisture content, protein, total lipid, and weight loss. Ash and moisture were determined according to the official methods (AOAC 1990). Protein was determined by following the ISO recommended method 937 (ISO 937:1978). Fat was determined by following the ISO recommended method 1443 (ISO 1443:1973). Water loss was calculated as follows equations:

Where:

- Mi

was the initial moisture of the sample

- Me

the moisture at the end of the treatment

Animals

A total of 35 healthy rats (4-week-old male Sprague–Dawley) were individually housed in stainless steel cages lined with wood shavings and fitted with wire mesh tops. The rats were acclimated to ambient temperature (23 ± 2 °C) and humidity and natural light/dark cycle. All rats were fed a standard rat chow and had free access to drinking water, and were kept in the facilities for at least 1 week prior to use. After confirming their normal health status at the end of the acclimation period, 30 rats were randomly allocated to five groups, each consisting of 10 rats and were then given the control or experimental diets for 90 days. The rats in Group I served as control. The rats in Groups II and III received orally 10 mg/kg body weight of α-apo-OTC or β-apo-OTC, respectively, per day.

Clinical observations

The behavior and appearance of all rats including coat condition, skin, eyes and excretions was monitored every 2 days throughout the study, including coat condition, skin, eyes and excretions.

Clinical pathology

Hematology and serum chemistry were conducted on all surviving rats on 90th day (the end of the trial). Rats were fasted for 12 h before collecting blood samples. Whole blood from the inner canthus was collected with and without anticoagulant and analyzed for white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), platelet count (PLT), urea nitrogen (BUN), serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was applied to the validation data, and the influence of cooking method and time, and meat species on the concentration of OTC and its degradation products was analyzed by ANOVA while means were compared using least significant difference (LSD).

The data was present as mean value and standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to evaluate the homogeneity variance of all of groups. ANOVA was used to compare the experimental groups. The response variable values of the treatment groups were compared to the control group using t-test. Differences between values were considered statistically significant at a P < 0.05.

All analyses were carried out using the SPSS statistics software version 20.

Results

HPLC analysis

Linear range, limit of detection and limit of qualification

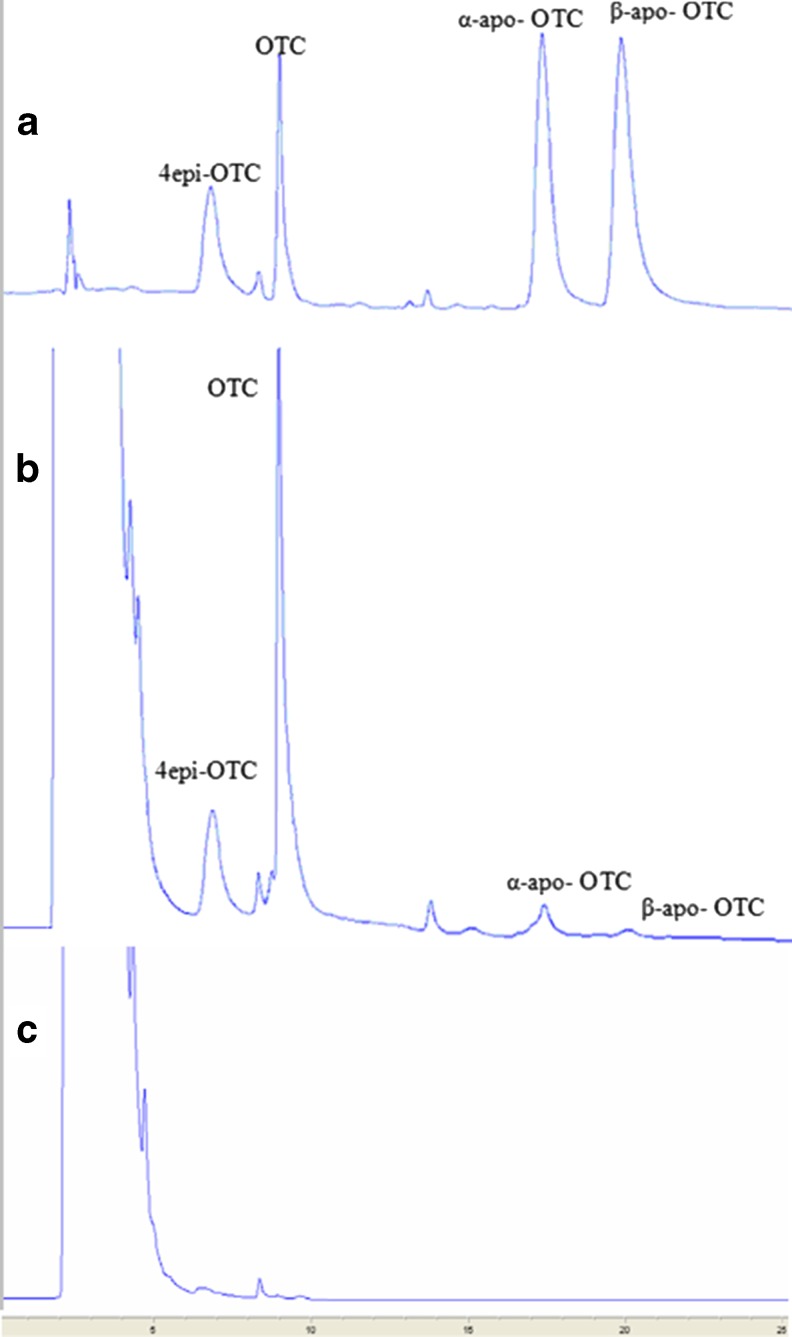

The linearity and correlations, of OTC, 4-epi-OTC, α-apo-OTC and β-apo-OTC were obtained from the calibration curves, which consisted of five points, by plotting peak areas of the standards having concentrations from 0.05 to 3.0 μg g−1. The coefficients of determination for OTC and its degradation products were greater than 0.998. Typical HPLC profiles of the TCs obtained from the standard solutions and the samples are as given in Fig. 1, which shows that OTC, 4-epi-OTC, α-apo-OTC and β-apo-OTC were well separated by the column, with elution times ranging from about 6.8 to 19.8 min. The optimal detection with the UV detector was found to be 253 nm after full spectra scans of OTC and its degradation products. The data listed in Table 2 demonstrates that the LOD for OTC, 4-epi-OTC, α-apo-OTC and β-apo-OTC ranged from 8 to 18 ng, LOQ was 26, 38, 47 and 53 ng OTC, 4-epi-OTC, α-apo-OTC and β-apo-OTC, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Typical chromatograms of a chromatographic standard solution; b microwave-treated pig sample; and c blank pig sample, thermally treated

Table 2.

Linearity, sensitivity, limit of detection and limit of quantitation of method

| Compound | Regression | Correlation coefficient (R) | LOD (ng g−1) | LOQ (ng g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4epi-Oxytetracycline | Y = 82.77X−0.71 | 0.9995 | 8 | 26 |

| Oxytetracycline | Y = 121.68X−4.41 | 0.999 | 12 | 38 |

| α-apo- Oxytetracycline | Y = 238.99X−1.50 | 0.9984 | 14 | 47 |

| β-apo- Oxytetracycline | Y = 303.81X−5.24 | 0.998 | 16 | 53 |

Recovery

In order to obtain optimal extraction efficiency for OTC and its degradation products, various extraction solutions were tested on pork (Table 3). These include McIlvaine buffer, citrate buffer as aqueous based extraction, McIlvaine buffer-EDTA/MeOH (75:25 v/v), and Citrate buffer-MeOH (75:25 v/v).

Table 3.

Mean recovery (percent), at a spiking level of 10 mg kg−1, for each compound under different extraction conditions

| Extracts | STD added pig meat (mg/kg) | 4epi-Oxytetracycline | Oxytetracycline | α-apo- Oxytetracycline | β -apo- Oxytetracycline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rec% | RSD% | Rec% | RSD% | Rec% | RSD% | Rec% | RSD% | ||

| Citrate buffer/MeOH (75:25 v/v) | 10 | 57.57 | 4.13 | 88.47 | 5.36 | 40.15 | 4.64 | 27.30 | 2.19 |

| McIlvaine buffer-EDTA/MeOH (75:25 v/v) | 10 | 44.51 | 6.14 | 85.91 | 4.94 | 31.48 | 3.75 | 20.76 | 4.98 |

| Citrate buffer | 10 | 41.67 | 2.95 | 84.14 | 1.71 | 29.56 | 4.47 | 11.03 | 4.79 |

| McIlvaine buffer-EDTA | 10 | 33.21 | 6.52 | 81.81 | 2.55 | 27.40 | 4.57 | 9.78 | 5.77 |

In this study, citrate buffer/MeOH (75:25 v/v) was selected for extraction of OTC and its degradation products from muscle samples as this gave solution gave the highest recovery from chicken and pork samples (Table 3).

Muscle samples were spiked with three concentrations for each compound (10, 20, and 30 μg g−1). Using standard addition methods the recoveries of OTC and its degradation compounds in the muscle samples were as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Recoveries (mean, %, n = 5) for OTCs and apo-OTCs in spiked raw samples

| Compound added μg g−1 | 4epi-OTC | OTC | α-apo-OTC | β-apo-OTC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC% | RSD% | REC% | RSD% | REC% | RSD% | REC% | RSD% | ||

| Chicken muscle | 10 | 58.07 | 7.50 | 88.60 | 1.57 | 41.74 | 4.04 | 29.06 | 3.21 |

| 20 | 62.46 | 6.42 | 88.22 | 3.30 | 45.05 | 2.05 | 32.90 | 2.56 | |

| 30 | 75.59 | 3.68 | 90.69 | 1.80 | 48.15 | 2.08 | 32.81 | 5.30 | |

| Pig muscles | 10 | 57.57 | 4.13 | 88.47 | 5.36 | 40.15 | 4.64 | 27.30 | 2.19 |

| 20 | 61.05 | 4.41 | 87.47 | 2.89 | 42.97 | 5.39 | 28.36 | 3.84 | |

| 30 | 73.02 | 3.38 | 89.25 | 2.51 | 42.30 | 2.51 | 29.69 | 4.15 | |

Formation of OTC degradation products in chicken and pork under different thermal processing conditions

The moisture, protein, fat, ash, and water loss (%) values of raw samples are given in Table 5. The compositions of the raw samples were similar to the findings of other researchers (Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007; Liao et al. 2009). As a result of cooking, the content of water decreased. The microwave-treated samples suffered higher water losses than the corresponding boiled samples, probably as a consequence of the differences between thermal treatments, sample nature (Table 5).

Table 5.

Chemical composition (%) of the raw pork and chicken and loss of water (%) on cooking

| Compound | Pork | Chicken | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%, w/w) | 71.75 ± 0.39 | 72.95 ± 0.48 | ||

| Protein (%, w/w) | 24.73 ± 0.28 | 25.48 ± 0.36 | ||

| Fat (%, w/w) | 2.29 ± 0.09 | 1.86 ± 0.1 | ||

| Ash (%, w/w) | 1.21 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.03 | ||

| Water loss (%) | Microwave | Boiling | Microwave | Boiling |

| 85.1 ± 1.47 | 36.2 ± 0.59 | 82.8 ± 1.01 | 33.4 ± 0.40 | |

The internal end-point temperature in the geometric center (calculated geometrically) of the cooked sample did not rise 100 °C in either of the two thermal treatments; and this temperature was not maintained for more than 15 min in boiling or 2 min for microwave cooking (Table 6).

Table 6.

Concentrations (μg g−1) of OTCs and apo-OTCs in meat samples under different thermal processing conditions

| Chicken | ||||||

| Boiling time (min) | 3 | 6 | 15 | |||

| Temperatured (°C) | 75.7 | 91.3 | 95.1 | |||

| Concentration | RSD% | Concentration | RSD% | Concentration | RSD% | |

| OTCs | 365.95a | 6.84 | 325.71b | 4.92 | 249.13c | 4.89 |

| Apo-OTCs | 1.06a | 1.54 | 2.15b | 3.71 | 3.62c | 2.67 |

| Microwaving time (min) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Temperatured (°C) | 92.9 | 95.8 | 92.4 | |||

| OTCs | 342.18a | 5.32 | 275.69b | 3.21 | 223.56c | 4.45 |

| Apo-OTCs | 1.52a | 2.79 | 2.44b | 5.06 | 4.68c | 5.52 |

| Pork | ||||||

| Boiling time (min) | 3 | 6 | 15 | |||

| Temperatured (°C) | 75.3 | 90.5 | 95.4 | |||

| OTCs | 360.09a | 3.65 | 317.08b | 4.17 | 236.56c | 7.96 |

| Apo-OTCs | 1.12a | 3.71 | 2.29b | 0.96 | 3.97c | 4.69 |

| Microwave time (min) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Temperatured (°C) | 94.2 | 96.7 | 92.5 | |||

| OTCs | 355.82a | 1.71 | 309.07b | 0.72 | 204.75c | 1.17 |

| Apo-OTCs | 1.76a | 6.47 | 2.67b | 2.37 | 6.01c | 6.69 |

a,b,cValues with different letters (a–c) within the same row are significantly different (p < 0. 05)

dInternal temperatures in geometric centre of cooked muscle samples

The effects of different thermal treatments on the degradation of OTC and the formation of OTC degradation products in chicken and pork are given in Table 6. Residual concentrations in the samples were expressed as the sum of the corresponding epimeric forms (OTCs = OTC + 4epi-OTC and apo-OTCs = α-apo-OTC + β-apo-OTC). The concentrations of apo-OTCs increased both tissues after thermal treatment, whereas residues of OTCs decreased. Both boiling and microwave treatments resulted in significant changes in OTCs and apo-OTCs concentrations. The formations of apo-OTCs, as well as reductions of OTCs, were dependent on the time of thermal treatments (Table 6).

The different thermal treatments had significant effects (p < 0.05) on the degradation kinetics of OTCs as well as the formation of apo-OTCs for both chicken and pork. From the results obtained it can be seen that at each time point, the type of meat significantly influenced the residual concentrations of apo-OTCs (except boiling treatment at 3 min).

Body and organ weights

The body weights and organ weights/percentages are presented in Table 7. No significant differences in body weight were observed between rats in the control group and those in the group treated with α-apo-OTC. In contrast, the body weights of those rats treated with β-apo-OTC showed significant changes compared with rats in the control group (p < 0.05). In the group treated with β-apo-OTC, there was significant increase in both absolute and relative weights of the liver and kidney as compared with the control animals, whereas no significant changes were observed in the weights of liver and kidney in the group treated with β-apo-OTC, as compared with control group (Table 7).

Table 7.

Body and organ weights and organ percentages for male rats treated with antibiotics as indicated (mean ± SD) (n = 10)

| Control | α-apo-OTC | β-apo-OTC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 359.02 ± 18.98 | 354.33 ± 20.26 | 341.57 ± 14.34* |

| Liver (g) | 13.43 ± 1.59 | 14.16 ± 1.84 | 14.97 ± 1.09* |

| Per body weight (%) | 3.76 ± 0.58 | 4.02 ± 0.61 | 4.39 ± 0.39* |

| Kidney (g) | 1.86 ± 0.14 | 1.93 ± 0.15 | 2.08 ± 0.15** |

| Per body weight (%) | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.05*** |

| Lungs (g) | 1.32 ± 0.12 | 1.35 ± 0.07 | 1.34 ± 0.10 |

| Per body weight (%) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.03* |

| Heart (g) | 0.96 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 0.88 ± 0.09* |

| Per body weight (%) | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.03 |

| Testis (g) | 2.32 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.15 | 2.16 ± 0.18 |

| Per body weight (%) | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.04 |

*Significant difference at p < 0.05 level, when compared with the control group

** Significant difference at p < 0.01 level, when compared with the control group

*** Significant difference at p < 0.001 level, when compared with the control group

Absolute heart and relative lung weights in the group treated with β-apo-OTC were also significantly increased in comparison to the control group. Absolute and relative heart/testis weights in the group treated with α-apo-OTC were slightly decreased, but no significant difference was detected compared with the control group.

Hematology

Hematological analyses from the group treated with β-apo-OTC were significantly different from those obtained from the control group (Table 8). However, no differences were observed between rats in the control group and those in the group treated with α-apo-OTC. In the group treated with β-apo-OTC, there was significant increased (p < 0.001) in both WBC and PLT as compared with the control animals. Although the WBC and PLT of rats in the group treated with α-apo-OTC were also slightly increased, no significant differences were detected compared with controls. RCB, HGB, HCT in the group treated with β-apo-OTC were significantly decreased when compared with that of the control group, whereas no significant changes occurred in the RCB, HGB and HCT of rats in the group treated with β-apo-OTC compared with control group.

Table 8.

Hematological analyses of male rats after 90 days feeding (mean ± SD) (n = 10)

| Control | α-apo-OTC | β-apo-OTC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (109/l) | 5.08 ± 0.29 | 5.5 ± 0.74 | 6.46 ± 0.67*** |

| RBC (1012/l) | 8.03 ± 0.76 | 8.43 ± 0.50 | 6.93 ± 0.65** |

| HGB (g/dl) | 13.61 ± 1.11 | 12.61 ± 1.27 | 10.96 ± 1.12*** |

| HCT (%) | 48.54 ± 6.74 | 48.75 ± 3.19 | 41.68 ± 3.52* |

| PLT (*109/l) | 451.31 ± 47.60 | 489.41 ± 50.56 | 542.28 ± 41.60*** |

*Significant difference at p < 0.05 level, when compared with the control group

**Significant difference at p < 0.01 level, when compared with the control group

***Significant difference at p < 0.001 level, when compared with the control group

Serum chemistry and pathological changes

The effects of the tetracycline degradation products on various serum constituents are given in Table 9. Significant differences in some constituents were observed between rats in the control group and those in the group treated with β-apo-OTC. However, changes in the serum constituents of the group treated with α-apo-OTC, did not show any significant differences compared with the controls. Both SGOT and SGPT in the group treated with β-apo-OTC were significantly increased in compared with the controls (p < 0.001). Although the SGOT and SGPT of rats in the group treated with α-apo-OTC were also slightly increased, the differences were not significant compared with controls. β-apo-OTC administration significantly decreased BUN concentration (p < 0.01) compared to the control group.

Table 9.

Serum enzyme activities and BUN in male rats after the 90 days of feeding (mean ± SD) (n = 10)

| Control | Α-apo-OTC | β apo-OTC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGOT (U/L) | 50.22 ± 4.25 | 54.01 ± 3.84 | 74.38 ± 13.37*** |

| SGPT (U/L) | 43.29 ± 6.12 | 45.02 ± 5.33 | 58.82 ± 9.48*** |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 51.54 ± 8.81 | 46.86 ± 4.09 | 64.24 ± 9.49** |

*Significant difference at p < 0.05 level, when compared with the control group

**Significant difference at p < 0.01 level, when compared with the control group

***Significant difference at p < 0.001 level, when compared with the control group

Discussion

In the present study, the separation of OTC and its degradation products were obtained using a reversed-phase (XBridge™ C18 250 × 4.6 mm I.D., 5 μm) at ambient temperature, with a mobile phase of acetonitrile-methanol-0.1 M phosphate-buffer pH 8. Under the conditions adopted, the analytes were fully separated within 20 min and had symmetrical peaks. These results are very similar to those reported by other authors (Smyrniotakis and Archontaki 2007; Fedeniuk et al. 1996). There was some variation between the recoveries of the OTC and its degradation products, possibly because of their different structures and the way in which they are bound in the sample matrix. That is, the extraction efficiency is affected by formation and nature of the analyte-protein conjugates. Also, citrate buffer has been found to be more effective than McIlvaine’s buffer because of its chelating ability (Javadi 2011; Samanidou et al. 2005). Thus, a combination of more than one reagent is recommended for removal of proteins and other macromolecules. We obtained low recoveries for 4-epi-OTC, α-apo-OTC, and β-apo-OTC, which were lower than the recovery of OTC (Tables 3 and 4) as has been reported by others (Fedeniuk et al. 1996). (Fedeniuk et al. 1996) reported that, the percentage recovery appeared to be dependent upon the initial concentration of OTC degradation products residue. When using solid phase extraction (SPE) for removal of α-apo-OTC, and β-apo-OTC from distilled water and porcine tissue the recoveries were low and irreproducible. This suggests that when using McIlvaine’s buffer together with SPE extraction other interactions in addition to hydrophobic phenomena become important. Other studies (Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007; Loke et al. 2003; Kuhne et al. 2001a, b) have also reported low recovery for TC/OTC degradation products in bone-derived feed, tissue, and manure samples. Accordingly, in our work (Table 3), citrate buffer/MeOH (75:25 v/v) extraction was the selected procedure for extracting OTC and its degradation compounds from chicken muscle and pig muscle samples since that mixture gave the greatest recoveries for each of the analyzed compounds.

The findings reported here are consistent with previous studies in which thermal treatments were shown to reduce the concentration of veterinary drug residues in foods; therefore decreasing the possible toxic effects of these compounds to consumers (Fedeniuk et al. 1996; Kuhne et al. 2001a, b; Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007; Furusawa and Hanabusa 2001; Javadi 2011; Lolo et al. 2006). At the same time, the thermal treatments resulted in the formation of the corresponding apo-OTCs in all treated meat samples. In the present study, the concentrations of apo-OTCs produced thermal treatment ranged from 0.7 to 1.2 % of the initial OTC content. Others have found that thermal treatments of meat containing TCs resulted in the formation of 0.8, 2.0, and 3.0 % of ATCs, and two unidentified compounds, respectively relative to the initial TC content (Gratacós-Cubarsí et al. 2007). In contrast, it has been reported (Rose et al. 1996) that no individual, closely related compound, such as 4-epi-oxytetracycline, α- or β-apo-oxytetracycline, forms a significant proportion of the breakdown products when meat containing OTC is cooked by various methods. Others have shown that the heat-induced toxic degradation products of tetracycline, namely anhydro-tetracycline and 4-epi-anhydro-tetracycline, were present in significant amounts following heat treatment of animal feed (Kuhne et al. 2001a, b).

The present study indicated that a dose of either β-apo-OTC (10 mg/kg body weight) when orally administered for 90 days, significantly decreased the body weight rats, and concomitantly, there were significant increases in both the absolute and relative weights of the liver and kidney as compared with the control animals. This did not result from malnutrition since they had a normal daily food intake. These findings demonstrate that β-apo-OTC has toxic effects of on rats. Further, the β-apo-OTC treated rats showed a decrease in the RBC count and HGB concentration in their blood, whereas the WBC count and the PLT count were both significantly increased compared with the control group.

In the present study, serum SGOT, SGPT and BUN activities were used as markers of liver and kidney damage. The animals treated with either β-apo-OTC showed a significant increased in serum SGOT, SGPT and BUN. Our data demonstrates that β-apo-OTC was toxic and appear to damage liver and kidney rats. The tetracycline degradation product, anhydro-4-epi-tetracycline was the only product which caused abnormal urinary findings of a type similar to the Fanconi-type syndrome. Severe, nephrotic changes were found in the kidneys of rats and dogs treated with anhydro-4-epi-tetracycline (Benitz and Diermeier 1964). Although several of the degradation products, including ATC and ACTC, have been shown to be potent antibiotics on tetracycline resistant bacterial strains, and, on the other hand, the products of chlortetracycline have adverse effects on fresh-water phytoplankton (Halling-Sorensen et al. 2002; Guo and Chen 2012), yet no studies have been conducted on the toxicity of the degradation products of OTC in animals.

Conclusion

The present results are in agreement with previous studies, which show that thermal treatments can reduce the concentration of veterinary drug residues in food. However, the results of the present investigation, together with those of recent studies on formation of OTC degradation products in food under different thermal treatments, indicates that relatively mild thermal processes, similar to those applied to meat during household cooking, may provoke the thermal breakdown of the original drug residue oxy-tetracycline and the formation of its degradation products.

The present study was designed to determine the toxicity of oxytetracycline degradation products upon oral administration to rats. The results demonstrated that the rats treated with α-apo-OTC for 90 days did not affect body/organ weights or certain blood- and serum-factors. The β-apo-OTC, on the other hand, exhibited significantly toxic effects on male rats, significantly decreased body weights and RBC counts, lowered HGB concentrations, and increased WBC and PLT counts. Concomitantly, there were increases in serum SGOT, SGPT and BUN. In summary, the toxic effects of β-apo-OTC in rats appeared to damage the liver and kidney, which ultimately led to necrosis of the hepatocytes. We suggest further studies to explore the mechanisms of liver and kidney toxicity by β-apo-OTC.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by 200903012 and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Contributor Information

VanHue Nguyen, Phone: +84-914078868, Email: huehuaf@gmail.com.

GuangHong Zhou, Phone: +86-25-84395376, FAX: +86-25-84395939, Email: ghzhou@njau.edu.cn.

References

- AOAC . Meat and meat products. In: Helrich K, editor. Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 15. Arlington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 1990. pp. 931–948. [Google Scholar]

- Benitz KF, Diermeier HF. Renal toxicity of tetracycline degradation products. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1964;115:930–935. doi: 10.3181/00379727-115-29082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra I, Roperts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;6:232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedeniuk RW, Ramamurthi S, McCurdy AR. Application of reversed-phase liquid chromatography and prepacked C18 cartridges for the analysis of oxytetracycline and related compounds. J Chromatogr B. 1996;667:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedeniuk RW, Shand PJ, McCurdy AR. Effect of thermal processing and additives on the kinetics of oxytetracycline degradation in pork muscle. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:2252–2257. doi: 10.1021/jf960725f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frimpter GW, Timpanelli AE, Eisenmenger WJ, Stein HS, Ehrlich LI. Reversible “Fanconi syndrome” caused by degraded tetracycline. JAMA. 1963;184(2):111–113. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03700150065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa N, Hanabusa R. Cooking effects on sulfonamide residues in chicken thigh muscle. Food Res Int. 2001;35:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00103-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia I, Sarabia LA, Cruz OM. Detection capability of tetracyclines analysed by a fluorescence technique: comparison between bilinear and trilinear partial least squares models. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;501:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2003.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratacós-Cubarsí M, Fernandez Garcia A, Pierre P, Valero-Pamplona A, Garcia-Regueiro J-A, Castellari M. Formation of tetracycline degradation products in chicken and pig meat under different thermal processing conditions. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:4610–4616. doi: 10.1021/jf070115n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo RX, Chen JQ. Phytoplankton toxicity of the antibiotic chlortetracycline and its UV light degradation products. Chemosphere. 2012;87:1254–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halling-Sorensen B, Sengelov G, Tjornelund J. Toxicity of tetracyclines and tetracycline degradation products to environmentally relevant bacteria, including selected tetracycline-resistant bacteria. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2002;42:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s00244-001-0017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICH Steering Committee (1996) Guidance for Industry: Q2 Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology Part 2. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH)

- ISO 1443:1973 (E) (1973) Meat and meat products – determination of total fat content, 1st ed. International organization for standardization

- ISO 937:1978 (E) (1978) Meat and meat products – determination of nitrogen content (reference), 1st ed. International organization for standardization

- Javadi A. Effect of roasting, boiling and microwaving cooking method on doxycline residues in edible tissues of poultry by microbial method. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;5(8):1034–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhne M, Hamscher G, Korner U, Schedl D, Wenzel S. Formation of anhydrotetracycline during a high-temperature treatment of animal-derived feed contaminated with tetracycline. Food Chem. 2001;75:423–429. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00230-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhne M, Korner U, Wenzel S. Tetracycline residues in meat and bone meals. Part 2: the effect of heat treatments on bound tetracycline residues. Food Addit Contam. 2001;18:593–600. doi: 10.1080/02652030118164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GZ, Xu XL, Zhou GH. Effects of cooked temperatures and addition of antioxidants on formation of HAAs in pork floss. J Food Proc Preserv. 2009;33:159–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2008.00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loke ML, Jespersen S, Vreeken R, Halling-Sørensen B, Tjørnelund J. Determination of oxytetracycline and its degradation products by high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in manure-containing anaerobic test systems. J Chromatogr B. 2003;783:11–23. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolo M, Pedreira S, Miranda JM, Vázquez BI, Franco CM, Cepeda A, Fente C. Effect of cooking on enrofloxacin residues in chicken tissue. Food Addit Contam. 2006;23:988–993. doi: 10.1080/02652030600904894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil JD, Martz VK, Korsrud GO, Salisbury CD, Oka H, Epstein RL, Barnes CJ. Chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, and tetracycline in edible animal tissues, liquid chromatographic method: collaborative study. J AOAC Int. 1996;79(2):405–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JJ, Campbell N, Conaghan T. Effect of cooking and cold storage on biologically active antibiotic residues in meat. J Hyg Camb. 1981;87:511. doi: 10.1017/S002217240006976X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Bygrave J, FWH H, Shearer G. The effect of cooking on veterinary drug residues in food: 4. Oxytetracycline Food Addit Contam A. 1996;13(3):275–286. doi: 10.1080/02652039609374409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanidou VF, Nikolaidou KI, Papadoyannis IN. Development and validation of an HPLC confirmatory method for the determination of tetracycline antibiotics residues in bovine muscle according to the European Union regulation 2002/657/EC. J Sep Sci. 2005;28:2247–2258. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby AR, Salama NA, Abou-Raya SH, Emam WH, Mehaya FM. Validation of HPLC method for determination of tetracycline residues in chicken meat and liver. Food Chem. 2011;124:1660–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyrniotakis CG, Archontaki HA. C18 columns for the simultaneous determination of oxytetracycline and its related substances by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography and UV detection. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;43:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropiło J, Kiszczak L, Piusiński W, Lenartowicz-Kubrat Z, Leszczyńska K. Subchronic toxicity of oxytetracycline (OTC) and the products of its thermal degradation after oral administration. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 1988;39(6):497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]