Abstract

Purpose

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of vision loss in individuals over the age of 65. Histopathological changes become evident in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a monolayer that provides metabolic support for the overlying photoreceptors, even at the earliest stages of AMD that precede vision loss. In a previous global RPE proteome analysis, we identified changes in the content of several mitochondrial proteins associated with AMD. Herein, we analyzed the sub-proteome of mitochondria isolated from human donor RPE graded with the Minnesota Grading System (MGS).

Methods

Human donor eye bank eyes were categorized into one of four progressive stages (MGS 1–4) based upon the clinical features of AMD. Following dissection of the RPE, mitochondrial proteins were isolated and separated based upon their charge and mass using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Protein spot densities were compared between the four MGS stages. Peptides from spots that changed significantly with MGS stage were extracted and analyzed using mass spectrometry to identify the protein.

Results

Western blot analyses verified that mitochondria were consistently enriched between MGS stages. The densities of eight spots increased or decreased significantly as a function of MGS stage. These spots were identified as the alpha, beta, and delta ATP synthase subunits, subunit VIb of the cytochrome C oxidase complex, mitofilin, mtHsp70, and the mitochondrial translation factor Tu.

Conclusions

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with AMD and further suggest specific pathophysiological mechanisms involving altered mitochondrial translation, import of nuclear-encoded proteins, and ATP synthase activity.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of blindness among older adults in developed nations.1, 2 Early clinical features of AMD include alterations in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a monolayer between the photoreceptors and choroid that supports retinal function and homeostasis. The quantity and extent of lipoproteinaceous deposits (drusen) that form between the RPE and choroid correlate with progressive stages of AMD. A significant number of patients with the early features of AMD progress to advanced stages with impaired central visual acuity, characterized by either central geographic atrophy (aAMD) or subretinal choroidal neovascularization with exudation (eAMD).3 The personal and public costs of AMD coupled with aging of the U.S. population create an urgent need to improve AMD prevention and treatment strategies over the next decade.4, 5 Further development of rational therapeutic interventions for AMD requires a greater understanding of basic AMD disease mechanisms.

Several lines of evidence indicate a role for mitochondria in the pathogenesis of AMD. First, mitochondria are the major source of superoxide anion in the cell,6 which can generate highly toxic hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide that damage the cell by reacting with proteins, DNA, and lipids. Oxidative stress appears to play an important role in AMD since human donor eyes affected by AMD contain increased levels of protein adducts resulting from the oxidative modification of carbohydrates and lipids7, 8 and higher levels of antioxidant enzymes9, 10. Second, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is more susceptible than nuclear DNA to damage from oxidation and blue light,11–13 and mtDNA damage in the retina and RPE accumulates with age.14, 15 Such damage may indirectly impair the function of mtDNA-encoded subunits of the electron transport chain and cause increased superoxide anion production, leading to further mtDNA damage and superoxide anion production in a self-perpetuating, destructive cycle.16, 17 Third, aging and cigarette smoking are two strong risk factors for AMD that are also associated with mitochondrial dysfunction,18–20 suggesting that aging and smoking may contribute to AMD through their effects upon mitochondrial function. Finally, two recent studies have found direct evidence of mitochondrial alterations in AMD.21, 22 A morphological analysis of human donor eyes affected by AMD found an accelerated loss of mitochondria number and cross-sectional area relative to normal age-related changes.21 Additionally, our previous proteomic analysis of the global human RPE proteome in AMD identified changes in the content of several mitochondrial proteins including mitochondrial heat shock proteins 60 and 70, ATP synthase β, and the voltage-dependent anion channel.22 To better characterize the mitochondrial changes associated with AMD, we analyzed the RPE mitochondrial sub-proteome from human donor eyes categorized with the Minnesota grading system (MGS).

Methods

Tissue procurement and grading

Briefly, globes were cooled in situ and stored at 4° C following post-mortem enucleation until processed as in previous studies.9, 23 Globes were processed according to the MGS, with the exception that both globes were photographed, dissected, and evaluated. After removing the vitreous, the neurosensory retina was gently peeled back and cut at the optic nerve head. The RPE was then carefully hydrodissected from Bruch's membrane using balanced saline solution and gentle blunt mechanical debridement. Tissues used in the present study were dissected fresh and stored at −80° C. There was no evidence during the clinical examination that the observed changes were associated with the cause of death. All research procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and had Institutional Review Board exemption from the human subjects committee at the University of Minnesota.

Mitochondrial enrichment

The RPE from each pair of globes was combined (for globes assigned the same MGS grade) and processed collectively. The protein yield from the macular RPE (central six millimeters) was insufficient for two-dimensional electrophoresis and therefore the peripheral RPE was used exclusively. Previous proteomic analyses have demonstrated that AMD is associated with biochemical changes in the peripheral RPE22 and many biochemical changes detected in the macula are also detected in the periphery.24 These results support the use of peripheral RPE in the present study.

RPE tissues were homogenized in a buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, and 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid. After adding 150 μL of buffer to the RPE from a single pair of globes, the tissue was subjected to two freeze-thaw cycles before gently passing the tissue suspension six times through a 26-gauge needle. The lysate was cleared of nuclei and intact cells by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 600 × g. Supernatants were removed and an additional 75 μL of buffer was added to the pellet, followed by a second homogenization and centrifugation. The second supernatant was combined with the first, and a 20 μL aliquot (homogenate) was removed for subsequent analyses. Mitochondria were then pelleted from the cleared cell lysate by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 13,000 × g. The supernatant, containing less dense organelles, membrane fragments, and soluble proteins (cytosol), was reserved for analysis of the preparation. The mitochondria-enriched pellet was washed once with buffer before resuspension in 8 M urea, 2 % 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, and 0.5% amidosulfobetaine-14 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) to yield the mitochondrial fraction. To increase the solubility of membrane proteins, the mitochondrial fraction was subjected to two freeze-thaw cycles and incubated for 30 minutes in a water bath sonicator. Protein content was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

2-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis

2D gel electrophoresis was performed as outlined22 and followed by staining with silver (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Preliminary analyses determined that loading 100 μg of mitochondrial protein yielded the greatest number of spots with a linear response (data not shown), and this protein load was used to rehydrate 3–11 nonlinear IPG strips for first-dimension focusing. Samples in the same MGS stage were combined as necessary to yield 100 μg of mitochondrial protein.

2D gel spot quantitation and analysis

A power analysis was performed to determine the fold change detectable given the study's sample size and variability. This analysis determined that with a sample size of seven gels, a 2.5-fold change could be detected on average with 90% power. Two statistical models, reflecting two possible patterns of disease-related change (linear and stage-specific), were used to test for significant spot quantity changes. The p value for each spot is indicated for a given model, with an uncorrected significance level of p < 0.05 and p < 0.025 after the Bonferroni correction.

Mass spectrometry (MS)

Peptide extraction from polyacrylamide gels, peptide mass fingerprinting, and sequencing by tandem MSMS were performed as described22 with the following modifications. Peptide masses were submitted to the Swiss-Prot database of human proteins using the Mascot (Matrix Science Inc., Boston, MA) search engine. The peptide mass fingerprinting searches used mass tolerance settings of 50 ppm, carbamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine (processing artifacts) as fixed and variable modifications, respectively, and 0 missed cleavages by trypsin. Protein identifications were considered verified by sequencing if the MS/MS spectra submitted to the Mascot Swiss-Prot human database yielded a significant (p < 0.05) match, with peptide and fragment mass tolerances set to 0.8 Da, carbamidomethyl as a fixed modification, and oxidation of methionine set as a variable modification.

One-dimensional gel electrophoresis and Western blotting

RPE fractions were separated using 16 cm × 16 cm polyacrylamide gels (12%, 1.5 mm thickness or 10%, 1 mm thickness) by the method of Laemmli and transferred as described25 except that for the 10% gels, the membrane was stained with Ponceau S Red before blocking, imaged, and destained with Tris-buffered saline (pH 11). Samples were also analyzed using 16 cm × 16 cm × 1.5 mm, 8–16 % gradient gels (Jule Inc., Milford, CT) and stained with Flamingo Pink fluorescent protein stain (Biorad). Fluorescent gels were excited with the DR88M transilluminator (Clare Chemical Research, Dolores, CO) and imaged with the Chemidoc system (Biorad). The density of individual bands was then quantified with the Quantity One software (Biorad) and tested by one-way ANOVA.

For blotting, the linear response of each primary antibody was verified for the protein load used. Antibodies directed against ATP synthase α (1:500, A21350), ATP synthase β (1:5000, A21351) and mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase 6 (1:1500, A31857) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Other antibodies were directed against Lamp-1 (1:250, 611042, BD Biosciences, San Jose CA), tyrosinase (1:500, 35–6000) and CD34 (1:1500, 07–3403, Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco CA), catalase (1:1000, ab16731, Abcam, Cambridge MA), heat shock protein 70 (1:5000, SPA-812) and manganese superoxide dismutase (1:2000, SOD-110, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:2000, D097-3S, MBL, Woburn, MA), and the voltage dependent ion channel (1:1000, 529532, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Standards were loaded for comparisons between gels, and reaction densities were normalized to either the homogenate reaction density or to the total lane density of Ponceau staining. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for colorimetric development as described25 and imaged with a GS-800 densitometer (Biorad). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat secondary antibodies were used in conjunction with the Supersignal West Dura chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) and imaged using a Chemidoc system (Biorad). The Quantity One software (version 4.6.1, Biorad) was used for densitometry.

Results

Human donor globes were graded with the Minnesota Grading System (MGS). Donor demographics are presented in Table 1. The average time from death to enucleation and death to tissue cryopreservation for all donors was 4.5 ± 1.8 hours and 16.9 ± 4.2 hours, respectively (mean ± SD). Age matching was not possible given the available donor tissues. However, the distribution of donor ages was similar for MGS stages 1–3, with an increase at stage 4 (Figure 1). Stage 1 of the MGS represents the control group. Stage 2 is characterized by the presence of numerous small, hard drusen in the macula and/or RPE pigmentary abnormalities. Stage 3 globes contain one or more large, soft drusen, numerous intermediate drusen, or nonmacular geographic atrophy. Globes categorized as MGS stage 4 contain central geographic atrophy or evidence of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization.

Table 1.

Donor demographics and clinical information

| MGS Grade | Sample size* | Mean age (yrs±SD) | Age Range (yrs) | Enuc† (hrs±SD) | Freeze‡ (hrs±SD) | Cause of death§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | F | M | ||||||

| 1 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 67±10 | 49–86 | 4.2±2.0 | 16.0±3.9 | Cancer (5), Organ failure (4), Sepsis (2), Vascular accident or hemorrhage (4) |

| 2 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 70±10 | 58–93 | 4.9±1.7 | 17.4±4.9 | Cancer (4), Myocardial infarct (1), Organ failure (2), Pneumonia (2), Sepsis (1), Vascular accident or hemorrhage (2) |

| 3 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 73±14 | 40–96 | 4.4±1.7 | 18.2±3.7 | Cancer (3), Cardiomyopathy (1), Myocardial infarct (1), Organ failure (2), Pancreatitis (1), Sepsis (2), Surgical complications (1), Vascular accident or hemorrhage (3) |

| 4 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 86±10 | 76–98 | 4.4±1.9 | 16.0±4.5 | Asthma (1), Cancer (1), Myocardial infarct (1), Organ failure (5), Pneumonia (2), Vascular accident or hemorrhage (1) |

Some protein samples from the same stage were combined.

Length of time interval from death to enucleation.

Length of time interval from death to freezing of dissected tissue.

Number of donors is indicated in parantheses. Organ failure includes respiratory failure and cardiac failure. Vascular accident or hemorrhage includes cerebral vascular accident.

Figure 1. Scatter plot comparison of human donor ages between MGS stages.

A horizontal bar indicates the mean age for each group. MGS 4 donors were significantly older than any other category of donors (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.005 and the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test). The differences between stage 1–3 means were not significant.

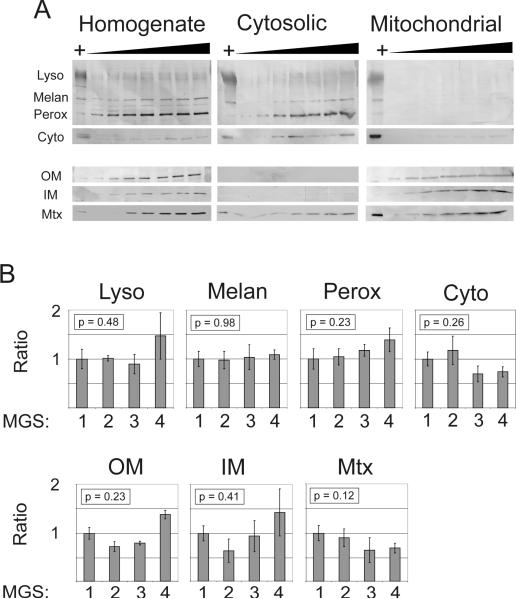

Since the yield from initial density gradient separations was insufficient for proteomic analysis, differential centrifugation was used to produce a fraction enriched for mitochondria (mitochondrial fraction) and a fraction depleted of mitochondria (cytosolic fraction). It was assumed that 1) the vast majority of protein in the mitochondrial fraction would normally be expressed in the mitochondria, and 2) the enrichment procedure would not be affected by MGS stage. Therefore, any content changes would be associated with AMD rather than differences in the enrichment of organelles between stages. We tested these assumptions by Western blot analysis of the fractions. First, increasing loads of protein from all three fractions were probed with organelle-specific antibodies (Figure 2A). All markers were detected in the homogenate. Lysosomal, peroxisomal, melanosomal, and cytosolic markers were clearly detected in the cytosolic but not mitochondrial fractions. Conversely, the outer (VDAC) and inner (ND6) membrane markers were clearly detected in the mitochondrial fraction but not the cytosolic fraction. The matrix protein MnSOD, however, could be readily detected in all three fractions and indicates some leakage from the mitochondrial matrix and intermembrane space.

Figure 2. Verification of mitochondrial enrichment by Western blotting.

A) Western blots of RPE fractions (homogenate, cytosolic, and mitochondrial) probed with antibodies specific for organelle markers (Lyso – lysosomes, LAMP-1 antibody; Melan – melanosomes, tyrosinase antibody; Perox – peroxisomes, catalase antibody; Cyto – cytosol, Hsp70 antibody; OM – outer mitochondrial membrane, VDAC antibody; IM – inner mitochondrial membrane, Complex I subunit 6/ND6 antibody; Mtx – mitochondrial matrix, MnSOD antibody). Blots indicate that the fractionation procedure resulted in selective depletion of mitochondria from the cytosolic fraction and selective enrichment of mitochondria in the mitochondrial fraction. Protein loads ranged from 5 to 35 μg of protein in 5 μg increments. The HeLa cell lysate positive control is indicated by `+'. Note that only a faint Hsp70 (Cyto) reaction was detected in the mitochondrial fraction after considerably overexposing the blot, as determined by comparing the positive control reaction intensities. B) Semi-quantitative comparison of subfractionation efficacy between MGS stages. Western blot measurements of organelle markers were compared for multiple samples from each stage. Each cytosol immune reaction was normalized to its corresponding homogenate immune reaction to account for total content differences between samples. Bars represent mean ± standard error, n = 6 for each group. No significant differences were detected for any marker by one-way ANOVA, suggesting that the subfractionation of cellular contents into cytosolic (i.e., nonmitochondrial) and mitochondrial fractions was not affected by MGS stage.

To determine whether the mitochondrial enrichment was effectively similar at each MGS stage, we probed a subset of samples using the same organelle markers. Since the mitochondrial fraction yield was not sufficient for both this analysis and the proteomic analysis, any changes in the enrichment process were measured indirectly by analyzing the homogenate and cytosolic fractions. It was assumed that a change in the mitochondrial fraction would correspond to a change in the cytosolic fraction, since greater organelle enrichment in the mitochondrial fraction would be accompanied by decreased organelle enrichment in the cytosolic fraction (e.g., more lysosomes in the mitochondrial fraction would mean fewer lysosomes in the cytosolic fraction). Each cytosolic reaction was normalized to its homogenate reaction to account for differences in total content between samples. No difference was detected between the four stages by one-way ANOVA (all p > 0.12; see Figure 2B) for any of the organelle markers or mitochondrial markers tested. These results indicate that the mitochondrial preparation selectively enriched for mitochondria and that enrichment effectiveness was not significantly different between MGS stages.

Mitochondrial samples were also tested for retinal and choroidal protein contamination (data not shown) by probing for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a retinal marker, and CD34, a choroidal marker expressed in the choriocapillaris.26 Little or no reactivity was detected for either marker. The mean ratio of GFAP signal for the mitochondrial fraction compared to a human retina positive control was 2.8 ± 3.0 % (mean ± standard deviation), and the ratio of CD34 signal compared to a human choroidal positive control was 1.1 ± 0.55 %. The relationship between MGS stage and contaminant ratio was not significant for either GFAP or CD34 (p = 0.33 and p = 0.51, respectively). These results indicate that the levels of contaminating protein from the retina and choroid are nearly undetectable and do not change as a function of MGS stage.

Having established that the preparation enriches for mitochondria and that the preparation effectiveness does not differ significantly between MGS stages, we analyzed the mitochondrial fraction using 2D gel electrophoresis (Figure 3). Preliminary observations indicated that a protein load of 100 μg of protein would yield the greatest number of spots within the linear range of the silver stain dye (data not shown). Automated spot detection and matching were verified manually, and individual spot densities were normalized to the total protein density to account for staining or protein load differences. An average of 440 spots were resolved per gel and 222 consistently resolved spots were tested for two disease-related patterns of change: a linear, progressive change determined by linear regression and any difference between stages determined by one-way ANOVA. Eight spots changed significantly according to one or both of these models (Figure 4, p < 0.05; after the Bonferroni correction, p < 0.025) and were excised for identification by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Initial protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS was verified by MS/MS sequencing (Table 2 and Figure 4). We deviated from this protocol for one spot, ATP synthase δ, which initially produced a non-significant match of three peptides by MALDI-TOF MS. Due to its small size and low content of lysine and arginine residues (trypsin cleavage sites), a maximum of only six peptides would have been measured from ATP synthase δ under ideal conditions. Sequence data for the two most intense peptide peaks in the MALDI-TOF spectrum matched exclusively to ATP synthase δ. The match was considered valid since we detected three of six possible peptides, sequences from the two most intense peaks matched to ATP synthase δ, and the observed mass and pI closely matched the predicted values.

Figure 3. Resolution of mitochondrial fraction proteins by 2D gel electrophoresis.

Representative gel demonstrating the resolution of 100 μg of human donor RPE mitochondrial fraction protein. Proteins were separated in the first dimension using a nonlinear pH gradient from 3 to 11 and in the second dimension using 13% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, then stained with silver. Spots that changed significantly by one-way ANOVA or linear regression analysis are boxed and numbered according to Table 2.

Figure 4. Protein spot densities and corresponding protein identity.

Individual spot densities were normalized to the total spot density for each gel and compared by one-way ANOVA (A) and linear regression (L). The test that reached significance and its associated p value are indicated above the normalized spot densities, which are reported as the mean ± standard error for each MGS stage. The number of measurements for each stage is indicated below the x-axis. Protein identifications (numbered according to Table 2) were obtained by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and verified by tandem mass spectrometry peptide sequencing. Note the y-axis scale difference between the top and bottom panels.

Table 2.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

| Accession | MALDI-TOF | MS/MS‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot # | Protein | Number* | Theoretical mass† / pI | # peptides | % coverage | Error (ppm) | # peptides |

| 1 | mtHsp70 | P38646 | 74 / 6.0 | 13 | 26 | 10 | 3 |

| 2 | ATP synthase α | P25705 | 60 / 9.2 | 21 | 54 | 13 | 2 |

| 3 | ATP synthase α | P25705 | 60 / 9.2 | 16 | 37 | 8 | 2 |

| 4 | ATP synthase δ§ | P30049 | 17 / 5.4 | 3 | 17 | 6 | 2 |

| 5 | Cytochrome C oxidase subunit VIb | P14854 | 10 / 6.5 | 7 | 74 | 7 | 2 |

| 6 | Mitofilin | Q16891 | 84 / 6.2 | 9 | 17 | 11 | 1 |

| 7 | Mitochondrial translation factor Tu | P49411 | 50 / 7.3 | 13 | 38 | 12 | 1 |

| 8 | ATP synthase β | P06576 | 57 / 5.3 | 13 | 41 | 2 | 1 |

Primary accession # from Swiss-Prot

Molecular weight in kDa

Includes peptides sequenced by MALDI-TOF tandem MS/MS and ESI-tandem MS/MS. Number of significantly identical peptides are indicated.

Coverage of ATP synthase δ was 53% of the total peptides expected within the measured mass range but was not sufficient for a significant MOWSE score.

The match to ATP synthase δ was significant after searching with the peptide sequences obtained by ESI-tandem MS/MS.

Since 2D gel electrophoresis does not efficiently resolve membrane-associated proteins or high molecular weight proteins, mitochondrial samples were also separated using 1D gradient gels (8–16%) and stained with Flamingo Pink fluorescent protein stain. No additional changes were found after comparing densities of individual protein bands, suggesting that there were no major protein changes beyond those detected by the 2D gel analysis (data not shown).

A significant number of the affected proteins were subunits of the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex that is responsible for generating ATP and maintaining the mitochondrial membrane potential. Hence, we sought to verify our original results by probing RPE homogenates with antibodies specific for ATP synthase α and β. There was no significant change in ATP synthase content when tested by one-way ANOVA (although there was a strong trend for the ATP synthase β ANOVA, p = 0.058; data not shown). Since there was a poor correspondence between the results obtained by 2D gel analysis of the mitochondrial fraction versus 1D Western blot analysis of the homogenate, we re-evaluated the 2D gels to better understand the discrepancy. For example, it has been noted that 1D Western blot and 2D gel results are more likely to correlate for proteins that migrate as a single spot in 2D gels compared to those that migrate as multiple spots (e.g., as charge trains or isoelectric variants).22 The one ATP synthase β spot and two ATP synthase α spots that decreased at later MGS stages did appear to migrate as part of a charge train at the approximate theoretical pI for each subunit. Both subunits contain predicted and/or experimentally verified phosphorylation and acetylation sites that could account for the observed charge trains.27, 28 Peptide mass fingerprint analysis identified three additional ATP synthase α spots and three additional ATP synthase β spots from the charge trains, although those spots were not affected by MGS stage (Figure 5A and data not shown). This suggests that the 1D Western blot measured both the ATP synthase spots that changed with MGS stage as well as those that did not. Consequently, 2D gel analysis may be more sensitive for detecting changes in specific post-translationally modified subsets of a total protein population.

Figure 5. 2D gel analysis of mitochondrial ATP synthase content.

A) Mass spectrometry analysis identified multiple ATP synthase α and β protein spots with altered isoelectric focusing points (isoelectric variants, arrows). Only a subset of the isoelectric variants changed significantly with MGS stage (numbered according to Table 2), based upon the initial 2D gel analysis. While the spots identified as ATP synthase α and β migrated as one of several ATP synthase isoelectric variants, ATP synthase δ appeared to migrate as a single spot. B) Total mitochondrial ATP synthase α, β, and δ content was estimated by summing the density of all identified spots (indicated by arrows in A). Mean density values and standard error of the mean were normalized to the greatest density value (MGS 2 for each subunit). The one-way ANOVA for each of the three ATP synthase subunits was significant (all p < 0.04).

To further understand the difference between ATP synthase content measured by 1D Western blot and 2D gel, the sum of all identified spot densities for each subunit was compared across MGS stages (Figure 5B). Unlike the 1D Western blot results, there was a significant effect of MGS stage on total ATP synthase α, β, and δ content (all p < 0.05). This difference may reflect technical differences between the two techniques or differences in mitochondrial and homogenate ATP synthase content. For example, ATP synthase spots migrating outside of the charge train would have contributed to the Western blot measurements but gone undetected by the 2D gel analysis. Additionally, the ATP synthase α and β subunits are imported from their site of translation in the cytosol. Any decrease in their import could have distinct effects upon measurement of the homogenate and mitochondrial ATP synthase content. It is also possible that components of the ATP synthase in RPE localize to the plasma membrane as noted for other cell types.29, 30 If so, then extra-mitochondrial ATP synthase protein would be measured in the homogenate but not mitochondrial fraction.

Discussion

We recently identified several mitochondrial protein changes in RPE isolated from donor eyes affected with AMD using a global proteomic analysis.22 In the present study, we sought to specifically identify changes in the mitochondrial sub-proteome by analyzing an enriched mitochondrial fraction from human donor RPE categorized using the Minnesota Grading System (MGS). Changes in the content of eight proteins crucial for mitochondrial translation, import of nuclear-encoded proteins, and metabolism were associated with AMD onset and progression. The use of proteomics to analyze human donor tissue has thus led to the identification of specific mitochondrial pathways affected by AMD.

Proteomic analysis of human tissue has many advantages, although there are some limitations. First, the post-mortem analysis of pathological human tissues is a highly valid approach to studying disease but may be limited by variations in the time interval from death to tissue collection and cryopreservation. Neither time interval, from death to enucleation nor death to the time of tissue freezing, varied significantly between the four MGS groups and consequently cannot account for any differences based upon MGS stage. Second, while we identified a number of novel mitochondrial protein changes by 2D gel analysis, some changes likely went undiscovered since 2D gels are less efficient at resolving membrane proteins and high molecular weight proteins. Two approaches were used to address these limitations: the use of an additional zwitterionic detergent (ASB-14) to increase protein solubility prior to first dimension focusing and a separate 1D gel analysis to detect changes in SDS-soluble membrane proteins and high molecular weight proteins. No additional changes were detected by the 1D gel analysis, suggesting that no major changes in protein content occurred beyond those detected by the 2D gel analysis. Every proteomic strategy has particular strengths and weaknesses, and despite the above limitations the present 2D gel analysis successfully compared the content of over 200 protein spots across four stages of AMD. Given the restricted amount of RPE tissue provided by a single donor (and far less mitochondrial protein), our methodology was successful in identifying AMD-related mitochondrial protein changes.

Unlike other proteomic studies that seek to identify the proteins expressed in an organelle or subcellular structure, the present study sought to identify mitochondrial changes associated with AMD and hence did not require a perfectly pure mitochondrial preparation. The loss of some mitochondrial protein or retention of some non-mitochondrial protein should not affect the measurement of AMD-related changes if the loss or contamination does not vary between MGS stages, which was found for every contaminant examined. Similarly, the loss of some matrix contents regrettably decreased the number of mitochondrial proteins measured by the 2D gel analysis but was not correlated with MGS stage and should not affect the validity of the results.

Converging evidence suggests that DNA damage occurs more readily in the mitochondrial than the nuclear genome, and that mtDNA damage could lead to RPE dysfunction. Blue light irradiation and treatment with hydrogen peroxide cause long-lasting mtDNA but not nuclear DNA mutations in cultured RPE cells.11–13 Several disorders caused by mtDNA deletions and mutations, such as maternally inherited deafness and diabetes (MIDD), MELAS (myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episode syndrome), specific forms of retinitis pigmentosa, and Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, can lead to retinopathy.31–33 Finally, mtDNA deletions in the RPE and retina increase with age and could contribute to the age-dependent onset of AMD.14, 15 Since most of the mitochondrial genome encodes either oxidative phosphorylation subunits (OXPHOS; 13 protein-encoding genes) or tRNAs required for mitochondrial translation33 (22 tRNA genes), mtDNA mutations and deletions often affect these specific mitochondrial systems.34

Polypeptides encoded by mtDNA are synthesized by mitochondria-specific ribosomes, tRNAs, and translation factors. The mitochondrial translation factor Tu (Tufm) delivers aminoacylated tRNAs to the mitochondrial ribosome as part of a mitochondrial translation elongation complex.35 Because of its central role in mitochondrial translation, increased or decreased levels of Tufm have direct consequences for the synthesis of mtDNA-encoded proteins. In a yeast model, overexpression of Tufm rescued a mitochondrial phenotype caused by the MELAS tRNA mutation.36 Overxpression of Tufm in fibroblasts from patients with a mitochondrial translation deficiency also restored the translation of mtDNA-encoded OXPHOS subunits and the assembly of OXPHOS complexes.37 On the other hand, a single point mutation in the Tufm tRNA binding site led to a dramatic loss of mitochondrial translation in patient-derived fibroblasts.38

While we did not measure mtDNA mutations or deletions directly, we did find a dramatic upregulation of Tufm at the earliest clinical stage of AMD (MGS stage 2). Tufm appears to be necessary for mitochondrial translation and is able to rescue translation defects, including those caused by tRNA mutations. These data indicate that changes in mitochondrial translation pathways are associated with an early AMD phenotype, possibly as a consequence of increased mtDNA damage in early AMD.

We also found AMD-related changes in the content of four OXPHOS subunits, including three from ATP synthase. The relatively consistent decrease in total ATP synthase α, β, and δ (Figure 5B) suggests a concerted loss of the ATP synthase complex between MGS stages 2 and 3. A subsequent loss of ATP synthase activity and decreased cellular ATP levels could be detrimental for RPE function and viability. Alternatively, a fraction of ATP synthase complexes exist as oligomeric supercomplexes that maintain mitochondrial morphology and the mitochondrial membrane potential.39–41 Since the F1 component of ATP synthase is believed to participate in its oligomerization,42 decreased content of the ATP synthase α, β, and δ subunits might also affect ATP synthase supercomplex oligomerization, mitochondrial morphology, and the mitochondrial membrane potential. Although the consequences are presently unknown, loss of the ATP synthase F1 subunits could be a pathological event occuring during early AMD.

The present results also indicate an association between AMD and deficient mitochondrial import of nuclear-encoded proteins. In both a previous global proteomic analysis of the RPE22 and the present mitochondrial sub-proteome analysis, we found a decrease in the content of the mitochondrial heat shock protein mtHsp70 associated with AMD. Decreased mtHsp70 content could be detrimental due to its pleiotropic functions in p53-mediated apoptosis, iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis, and mitochondrial calcium regulation.43–45 However, mtHsp70 is also required for the ATP-dependent import of nuclear-encoded proteins into the mitochondrial matrix.46 Decreased mtHsp70-dependent import could consequently affect many matrix-localized functions (including the TCA cycle and β-oxidation).

In summary, we performed a mitochondrial sub-proteome analysis of RPE categorized using the Minnesota Grading System. We replicated our previous observation that decreased content of mtHsp70 is associated with AMD and identified novel associations between AMD and both the decreased content of three ATP synthase subunits and increased content of a mitochondrial translation factor. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that mtDNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction contribute to the pathogenesis of AMD. The identification of mitochondrial translation, import, and ATP synthase protein changes using proteomic analysis of clinically staged human donor tissue represents a powerful approach for identifying putative AMD disease mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Minnesota Lions and Minnesota Lions Eye Bank personnel for their assistance in procuring eyes for this study, and the Mass Spectrometry Consortium for the Life Sciences (University of Minnesota) for technical assistance.

Financial support: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health EY014176 (DAF) and AG025392 (TWO), a Career Development Award from the American Federation for Aging Research and Foundation Fighting Blindness (DAF), American Health Assistance Foundation, Minnesota Medical Foundation, Minnesota Lions Macular Degeneration Center, the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center and Graduate School, the Fesler-Lampert Foundation, and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology from the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None

References

- 1.Buch H, Vinding T, La Cour M, Appleyard M, Jensen GB, Nielsen NV. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness among 9980 Scandinavian adults: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congdon N, O'Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MD, Gangnon RE, Lee LY, et al. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1484–1498. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman AL, Yu F. Eye-Related Medicare Costs for Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration from 1995 to 1999. Ophthalmology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell J, Bradley C. Quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2006;4:97. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. The Journal of physiology. 2003;552:335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, et al. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howes KA, Liu Y, Dunaief JL, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3713–3720. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decanini A, Nordgaard CL, Feng X, Ferrington DA, Olsen TW. Changes in select redox proteins of the retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007;143:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank RN, Amin RH, Puklin JE. Antioxidant enzymes in the macular retinal pigment epithelium of eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. American journal of ophthalmology. 1999;127:694–709. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballinger SW, Van Houten B, Jin GF, Conklin CA, Godley BF. Hydrogen peroxide causes significant mitochondrial DNA damage in human RPE cells. Experimental eye research. 1999;68:765–772. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godley BF, Shamsi FA, Liang FQ, Jarrett SG, Davies S, Boulton M. Blue light induces mitochondrial DNA damage and free radical production in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21061–21066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King A, Gottlieb E, Brooks DG, Murphy MP, Dunaief JL. Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species mediate blue light-induced death of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Photochemistry and photobiology. 2004;79:470–475. doi: 10.1562/le-03-17.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barreau E, Brossas JY, Courtois Y, Treton JA. Accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in human retina during aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barron MJ, Johnson MA, Andrews RM, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in ageing macular photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:3016–3022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang FQ, Godley BF. Oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial DNA damage in human retinal pigment epithelial cells: a possible mechanism for RPE aging and age-related macular degeneration. Experimental eye research. 2003;76:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos JH, Hunakova L, Chen Y, Bortner C, Van Houten B. Cell sorting experiments link persistent mitochondrial DNA damage with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptotic cell death. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1728–1734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia L, Liu Z, Sun L, et al. Acrolein, a toxicant in cigarette smoke, causes oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in RPE cells: protection by (R)-alpha-lipoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:339–348. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein R, Peto T, Bird A, Vannewkirk MR. The epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. American journal of ophthalmology. 2004;137:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro A, Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. American journal of physiology. 2007;292:C670–686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feher J, Kovacs I, Artico M, Cavallotti C, Papale A, Balacco Gabrieli C. Mitochondrial alterations of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Neurobiology of aging. 2006;27:983–993. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordgaard CL, Berg KM, Kapphahn RJ, et al. Proteomics of the retinal pigment epithelium reveals altered protein expression at progressive stages of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:815–822. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen TW, Feng X. The Minnesota Grading System of eye bank eyes for age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4484–4490. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ethen CM, Reilly C, Feng X, Olsen TW, Ferrington DA. The proteome of central and peripheral retina with progression of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2280–2290. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapphahn RJ, Ethen CM, Peters EA, Higgins L, Ferrington DA. Modified alpha A crystallin in the retina: altered expression and truncation with aging. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15310–15325. doi: 10.1021/bi034774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhutto IA, Kim SY, McLeod DS, et al. Localization of collagen XVIII and the endostatin portion of collagen XVIII in aged human control eyes and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1544–1552. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hojlund K, Wrzesinski K, Larsen PM, et al. Proteome analysis reveals phosphorylation of ATP synthase beta -subunit in human skeletal muscle and proteins with potential roles in type 2 diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10436–10442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SC, Sprung R, Chen Y, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Molecular cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto K, Shimizu N, Obi S, et al. Involvement of cell-surface ATP synthase in flow-induced ATP release by vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01385.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez LO, Jacquet S, Esteve JP, et al. Ectopic beta-chain of ATP synthase is an apolipoprotein A-I receptor in hepatic HDL endocytosis. Nature. 2003;421:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nature01250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Latvala T, Mustonen E, Uusitalo R, Majamaa K. Pigmentary retinopathy in patients with the MELAS mutation 3243A-->G in mitochondrial DNA. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2002;240:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith PR, Bain SC, Good PA, et al. Pigmentary retinal dystrophy and the syndrome of maternally inherited diabetes and deafness caused by the mitochondrial DNA 3243 tRNA(Leu) A to G mutation. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrg1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenaz G, Baracca A, Carelli V, D'Aurelio M, Sgarbi G, Solaini G. Bioenergetics of mitochondrial diseases associated with mtDNA mutations. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004;1658:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodnina MV, Gromadski KB, Kothe U, Wieden HJ. Recognition and selection of tRNA in translation. FEBS letters. 2005;579:938–942. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feuermann M, Francisci S, Rinaldi T, et al. The yeast counterparts of human `MELAS' mutations cause mitochondrial dysfunction that can be rescued by overexpression of the mitochondrial translation factor EF-Tu. EMBO reports. 2003;4:53–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smeitink JA, Elpeleg O, Antonicka H, et al. Distinct clinical phenotypes associated with a mutation in the mitochondrial translation elongation factor EFTs. American journal of human genetics. 2006;79:869–877. doi: 10.1086/508434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valente L, Tiranti V, Marsano RM, et al. Infantile encephalopathy and defective mitochondrial DNA translation in patients with mutations of mitochondrial elongation factors EFG1 and EFTu. American journal of human genetics. 2007;80:44–58. doi: 10.1086/510559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arselin G, Vaillier J, Salin B, et al. The modulation in subunits e and g amounts of yeast ATP synthase modifies mitochondrial cristae morphology. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40392–40399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bornhovd C, Vogel F, Neupert W, Reichert AS. Mitochondrial membrane potential is dependent on the oligomeric state of F1F0-ATP synthase supracomplexes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13990–13998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minauro-Sanmiguel F, Wilkens S, Garcia JJ. Structure of dimeric mitochondrial ATP synthase: novel F0 bridging features and the structural basis of mitochondrial cristae biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12356–12358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503893102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia JJ, Morales-Rios E, Cortes-Hernandez P, Rodriguez-Zavala JS. The inhibitor protein (IF1) promotes dimerization of the mitochondrial F1F0-ATP synthase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12695–12703. doi: 10.1021/bi060339j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lill R, Muhlenhoff U. Iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in eukaryotes: components and mechanisms. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2006;22:457–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;175:901–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wadhwa R, Yaguchi T, Hasan MK, Mitsui Y, Reddel RR, Kaul SC. Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein. Experimental cell research. 2002;274:246–253. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stojanovski D, Rissler M, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Mitochondrial morphology and protein import--a tight connection? Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1763:414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]