Abstract

Background

Transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon to the posterosuperior part of the rotator cuff is an option in active patients with massive rotator cuff tears to restore shoulder elevation and external rotation. However, it is unknown whether this treatment prevents progression of cuff tear arthropathy.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the observed improvement in shoulder function in the early postoperative period with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears will be permanent or will deteriorate in the midterm period (at 1–5 years after surgery).

Methods

During a 6-year period, we performed 11 latissimus dorsi tendon transfers in 11 patients for patients with massive, irreparable, chronic tears of the posterosuperior part of the rotator cuff (defined as > 5 cm supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon tears with Goutallier Grade 3 to 4 fatty infiltration on MRI), for patients who were younger than 65 years of age, and had high functional demands and intact subscapularis function. No patients were lost to followup; minimum followup was 12 months (median, 33 months; range, 12–62 months). The mean patient age was 55 years (median, 53 years; range, 47–65 years). Shoulder forward elevation, external rotation, and Constant-Murley and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons scores were assessed. Pain was assessed by a 0- to 10-point visual analog scale. Acromiohumeral distance and cuff tear arthropathy (staged according to the Hamada classification) were evaluated on radiographs.

Results

Shoulder forward elevation, external rotation, Constant-Murley scores, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons scores improved at 6 months. However, although shoulder motion values and Constant-Murley scores remained unchanged between the 6-month and latest evaluations, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons scores decreased in this period (median, 71; range, 33–88 versus median, 68; range, 33–85; p = 0.009). Visual analog scale scores improved between the preoperative and 6-month evaluations but then worsened (representing worse pain) between the 6-month and latest evaluations (median, 2; range, 0–5 versus median, 2; range, 1–6; p = 0.034), but scores at latest followup were still lower than preoperative values (median, 7; range, 4–8; p = 0.003). Although acromiohumeral distance values were increased at 6 months (median, 8 mm; range, 6–10 mm; p = 0.023), the values at latest followup (median, 8 mm; range, 5–10 mm) were no different from the preoperative ones (mean, 7 mm; range, 6–9 mm; p > 0.05). According to Hamada classification, all patients were Grade 1 both pre- and postoperatively, except one who was Grade 3 at latest followup.

Conclusions

The latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may improve shoulder function in irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. However, because the tenodesis effect loses its strength with time, progression of the arthropathy should be expected over time. Nevertheless, latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may help to delay the need for reverse shoulder arthroplasty for these patients.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Massive rotator cuff tears are disabling conditions that cause severe functional impairment and pain. The main functional deficit resulting from a massive tear in the posterosuperior part of the rotator cuff is weakness in external rotation (ER) and forward elevation (FE). The absence of cuff mass in the subacromial space and the loss of the depressor effect of the cuff eventually result in superior migration of the humeral head, which leads to the development of cuff tear arthropathy [12].

Degenerative changes, especially advanced fatty infiltration, make primary cuff repair difficult or impossible for some chronic massive rotator cuff tears. If left untreated, the cuff tear arthropathy may develop [5], and reverse shoulder arthroplasty is an option for some of these patients [4]. Some patients may have functional impairments without any pathological changes on radiographs [12]. For these patients, functional improvement may be achieved while preserving the shoulder and avoiding arthroplasty by rerouting the intact muscle-tendon units. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer as described by L’Episcopo is a valuable treatment option for young patients with massive rotator cuff tears [15].

The function of the shoulder is the sum of different moments created by various muscles acting on it along with the anatomical features of the shoulder. The transfer of the tendon changes the direction of the moment and the tendon excursion. The change in excursion may stretch the tendon, which may create a tenodesis effect. The change in the direction transforms an internal rotator to an external rotator and forward flexor, which can be defined as the transfer effect. The functional outcome itself is a combination of both effects and the tenodesis effect may allow rebalancing of the forces and more effective deltoid function. Although it is difficult to separate the transfer and tenodesis effect, relating the shoulder motion to transfer and acromiohumeral distance to tenodesis is a simple way to analyze their effects separately [5, 21].

It has been well documented with that latissimus dorsi tendon transfer improves shoulder function in patients with massive rotator cuff tears [1, 6, 7]. However, few studies compare the improvement obtained in the early and midterm postoperative periods [10, 14]. In this study, we tried to show whether the improvement in shoulder function in the early postoperative period (6 months) with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears will be permanent or deteriorate in midterm period (by 1–5 years after surgery).

Patients and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed patients with irreparable massive rotator cuff tears treated by the senior surgeon (MD) with latissimus dorsi tendon transfers as described by L’Episcopo between 2007 and 2012 [15]. Irreparable massive chronic tears of the posterosuperior part of rotator cuff were defined as more than 5-cm supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon tears with Goutallier Grade 3 to 4 fatty infiltration as seen on MRI [16, 17]. Inclusion criteria were age younger than 65 years, high functional demands, and intact subscapularis function.

During this time, the senior surgeon treated a total of 50 patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears with surgery. Twenty-four patients with massive tears extending to subscapularis tendons and advanced cuff tear arthropathy who were older than 65 years were treated with reverse shoulder arthroplasty and were excluded from the study for that reason. Fifteen low-demand patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears who were older than 65 years and who had no signs of arthropathy were treated with arthroscopic débridement, biceps tenotomy, and partial repair. These patients also were excluded. Eleven shoulders of 11 patients underwent latissimus dorsi tendon transfer and were therefore included in the study (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 54 years (range, 47–63 years). Seven patients were women and four were men. Four patients had Grade 3 fatty infiltration and seven had Grade 4 fatty infiltration. The minimum followup was 12 months (mean, 38 months; range, 12–62 months; SD, 18.5 months). No patients were lost to followup.

Table 1.

Preoperative patient data and followup times

| Patient number | Sex | Age | Prior RC repair | Goutallier grade | Followup (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 63 | None | 4 | 62 |

| 2 | F | 65 | Yes | 4 | 58 |

| 3 | M | 48 | Yes | 4 | 12 |

| 4 | F | 55 | Yes | 3 | 50 |

| 5 | M | 53 | None | 4 | 38 |

| 6 | M | 48 | None | 3 | 22 |

| 7 | F | 47 | None | 3 | 15 |

| 8 | F | 51 | None | 4 | 34 |

| 9 | M | 49 | None | 3 | 61 |

| 10 | M | 62 | None | 4 | 26 |

| 11 | M | 60 | None | 4 | 40 |

RC = rotator cuff; M = male; F = female.

Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer was the initial treatment method in eight patients, and three patients had previous arthroscopic rotator cuff repair surgeries. Before undergoing surgery, all patients received antiinflammatory drug treatment with a physical therapy program for 3 months focused on strengthening of the remaining cuff muscles and increasing shoulder motion.

The principal indications for latissimus dorsi tendon transfer were pain and weakness.

Surgical Technique

The patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position under general anesthesia. To expose the rotator cuff tear, a transverse incision was made on the lateral aspect of the acromion. Subacromial bursectomy and débridement were performed and the rotator cuff tear was visualized. The rotator cuff tendons were mobilized and checked to determine whether a double-row repair was feasible. When the repair seemed not feasible, the procedure continued with latissimus dorsi transfer as planned preoperatively. No partial repair of the massive tear was performed because the primary surgeon thought it would not have any beneficial effect when there is advanced fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff. Biceps tenodesis was performed in all patients. To expose the latissimus dorsi tendon, a longitudinal incision on the posterior axillary fold extending downward was made. While paying attention to the adjacent neurovascular structures, the latissimus dorsi tendon was dissected and isolated from the teres major tendon. Afterward, the latissimus dorsi tendon was sharply cut from the humerus as close as possible to its insertion to acquire the longest tendon length possible.

The tendon was grasped with locking Krackow sutures. A soft tissue tunnel deep to the deltoid muscle was prepared and the latissimus dorsi tendon was pulled to the previous incision through this tunnel. While keeping the shoulder in neutral position, the tendon was fixed to the posterosuperior part of the humeral head with two, three, or four suture anchors (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL, USA) depending on the size of the cross-section of the tendon. After careful hemostasis, the incisions were closed.

Postoperative Care

The shoulder was immobilized in a 30° abduction sling for 6 weeks followed by active assisted exercises in the supine position for 2 weeks. After the eighth week, active assisted exercises were performed in the standing position. Between the 12th and 16th weeks, active strengthening exercises for the shoulder muscles were encouraged.

Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation

A standardized preoperative physical examination to document shoulder motion and muscle strength was performed for all patients by a single orthopaedist (AE). All AP shoulder radiographs were remeasured by the same orthopaedist at two time points in random order. The maximum intraobserver difference for the same radiograph was 0.8 mm (range, 0–0.8 mm). For functional outcome (tendon transfer effect), we assessed FE and ER values; the Constant-Murley score, which focuses on the ability to perform daily activities; and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, which mainly analyzes the effect of pain on shoulder function. Pain elicited during activities was also assessed on a 0- to 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing most severe pain.

The tenodesis effect was assessed by measuring the acromiohumeral distance on true shoulder AP radiographs. The true shoulder AP view was acquired by placing the cassette parallel to the plane of the scapula and directing the x-ray beam perpendicular to the cassette. All the radiographs were obtained by the same x-ray machine using a 1:1 caliber.

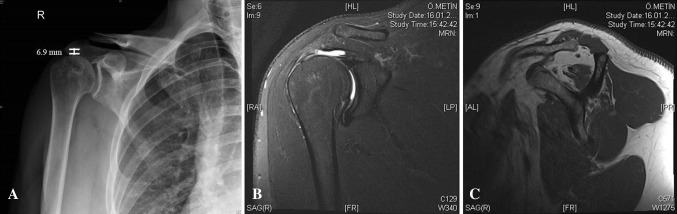

Cuff tear arthropathy was staged according to the classification of Hamada et al. [11] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1A–C.

(A) A preoperative shoulder AP radiograph shows Grade 1 arthropathy. Acromiohumeral distance is 6.9 mm. Shoulder (B) coronal and (C) sagittal MR images show a massive retracted rotator cuff tear with Grade 3 fatty infiltration.

Patient evaluation values recorded at 6 months postoperatively were used to indicate early results and those recorded at the latest followup were used to indicate midterm results.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are expressed as median and range. Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were used for the comparisons of FE, ER, Constant-Murley score, ASES score, and acromiohumeral distance values among evaluation times (preoperative, 6-month followup, latest followup). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® 11.0 for Windows® (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

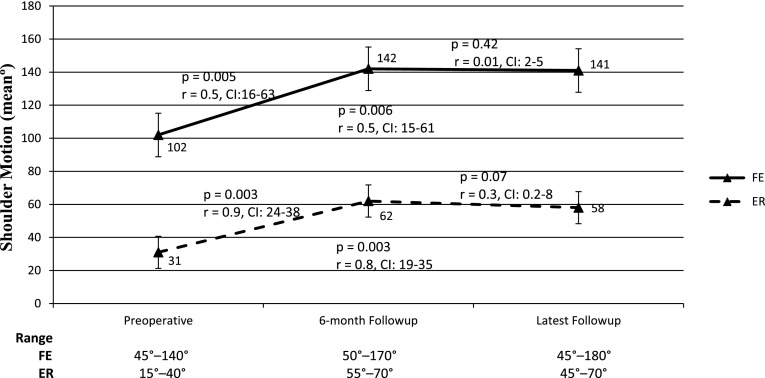

Compared with the preoperative values (median, 100°; range, 45°–140° and median, 30°; range, 15°–40°), the median FE and ER values increased to 150° (range, 50°–170°) and 60° (range, 55°–70°) at 6-month followup (p = 0.005, r = 0.5, confidence interval [CI], 16–63 and p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 24–38, respectively) and 145° (range, 45°–180°) and 60° (range, 45°–70°) at latest followup (p = 0.006, r = 0.5, CI, 15–61 and p = 0.003, r = 0.8, CI, 19–35, respectively) (Table 2; Fig. 2). The mean FE and ER values did not change between the 6-month and latest evaluations (p = 0.42, r = 0.01, CI, 2–5 and p = 0.07, r = 0.3, CI, 0.2–8, respectively).

Table 2.

Active shoulder motion

| Patient number | Forward elevation (°) | External rotation (°) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | |

| 1 | 90 | 160 | 160 | 15 | 60 | 60 |

| 2 | 60 | 50 | 45 | 40 | 65 | 60 |

| 3 | 45 | 165 | 160 | 30 | 60 | 70 |

| 4 | 160 | 170 | 180 | 30 | 60 | 50 |

| 5 | 100 | 140 | 140 | 35 | 55 | 45 |

| 6 | 140 | 155 | 160 | 50 | 70 | 70 |

| 7 | 95 | 150 | 140 | 20 | 70 | 65 |

| 8 | 110 | 150 | 145 | 35 | 55 | 50 |

| 9 | 120 | 150 | 150 | 30 | 65 | 60 |

| 10 | 90 | 140 | 140 | 30 | 60 | 55 |

| 11 | 120 | 135 | 130 | 25 | 60 | 50 |

| Mean (SD) | 102 (32.9) | 142 (32.4) | 141 (34.7) | 31 (9.4) | 62 (5.1) | 58 (8.5) |

Fig. 2.

A graph shows the changes in shoulder FE and ER during followup.

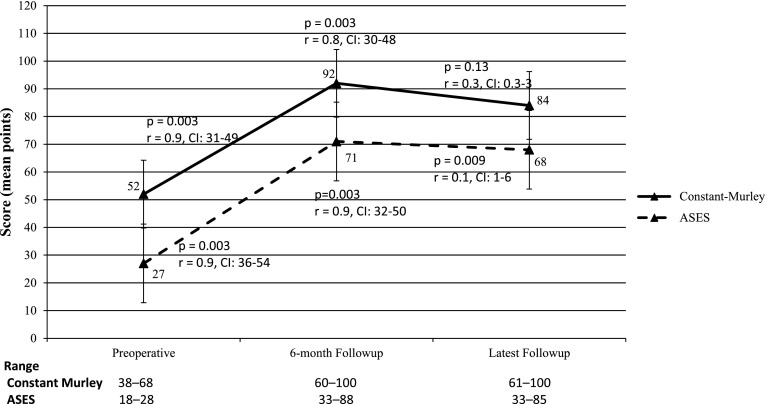

The median Constant-Murley and ASES scores increased from 48 (range, 38–68) and 26 (range, 18–28) preoperatively to 95 (range, 60–100) and 71 (range, 33–88) at 6-month followup (p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 31–49 and p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 36–54, respectively) and 84 (range, 61–100; SD, 11.3) and 68 (range, 33–85; SD, 13.7) at latest followup (p = 0.003, r = 0.8, CI, 30–48 and p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 32–50, respectively) (Table 3; Fig. 3). Although the mean Constant-Murley score did not change between the 6-month and latest evaluations (p = 0.13, r = 0.3, CI, 0.3–3), the mean ASES score decreased (p = 0.009, r = 0.1, CI, 1–6). However, the mean ASES score at latest followup was still higher than the mean preoperative value (p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 32–50).

Table 3.

Functional and pain scores

| Patient number | Constant-Murley score (points) | ASES score (points) | VAS pain score (points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | |

| 1 | 40 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 88.3 | 85.2 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 48 | 60 | 61 | 18.3 | 32.8 | 33.3 | 8 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | 38 | 100 | 100 | 20.3 | 80.2 | 75.8 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 26.6 | 70.2 | 68.3 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | 68 | 100 | 100 | 51.6 | 87.5 | 83.3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 62 | 95 | 95 | 27.3 | 67.4 | 65.5 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | 44 | 90 | 90 | 26.7 | 72.1 | 61.6 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | 58 | 95 | 90 | 25 | 70.5 | 63.3 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 55 | 95 | 90 | 28.3 | 75.4 | 66.8 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | 47 | 90 | 90 | 24.4 | 71.3 | 70.2 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | 46 | 90 | 85 | 25.7 | 69.4 | 70.5 | 8 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean (SD) | 52 (10.5) | 92 (11.5) | 84 (11.3) | 27 (8.9) | 71 (14.7) | 68 (13.7) | 6.9 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.5) |

ASES = American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; VAS = visual analog scale.

Fig. 3.

A graph shows the changes in the Constant-Murley and ASES scores during followup.

The median preoperative VAS score was 7 (range, 4–8), which decreased to 2 (range, 0–5) at 6-month followup (p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 4–7) and 3 (range, 1–6) at latest followup (p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 3–5) (Table 3). Although the mean VAS score increased between the 6-month and latest evaluations (p = 0.034, r = 0.4, CI, 0.8–1), the mean VAS score at latest followup was still lower than the mean preoperative value (p = 0.003, r = 0.9, CI, 3–5).

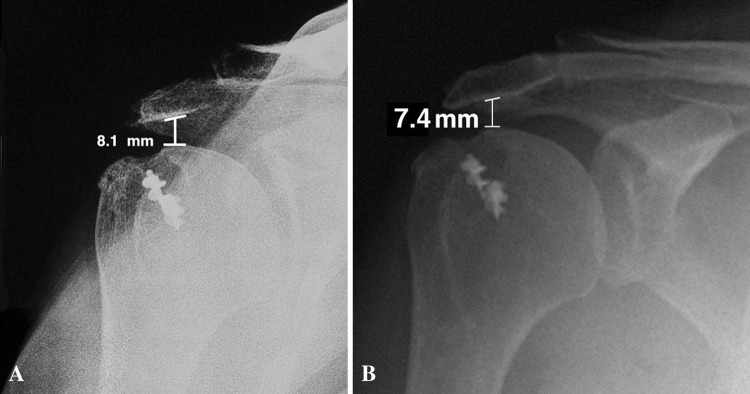

The median preoperative acromiohumeral distance was 7 mm (range, 6–9 mm), which increased to 8 mm (range, 6.2–9.8 mm) at 6-month followup (p = 0.023, r = 0.6, CI, 0.6–2) and 8 mm (range, 5.2–9.5 mm) at latest followup (p = 0.05, r = 0.3, CI, 1–2) (Table 4). Although the mean acromiohumeral distance decreased between the 6-month and latest evaluations (p = 0.004, r = 0.4, CI, 0.4–1), the mean acromiohumeral distance at latest followup was still higher than the mean preoperative value (p = 0.05, r = 0.3, CI, 1–2). According to the Hamada classification, all patients were Grade 1 both preoperatively and postoperatively, except one who was Grade 3 at latest followup.

Table 4.

Acromiohumeral distance

| Patient number | Acromiohumeral distance (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 6-month followup | Latest followup | |

| 1 | 9 | 9.8 | 9.49 |

| 2 | 8 | 6.2 | 5.17 |

| 3 | 6 | 7.5 | 7.05 |

| 4 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 7.56 |

| 5 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 8 |

| 6 | 6.6 | 9.1 | 8.2 |

| 7 | 6 | 9.4 | 7.6 |

| 8 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 6.9 |

| 9 | 6 | 8.5 | 6.6 |

| 10 | 7 | 8.4 | 7.7 |

| 11 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 7.4 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (0.9) | 8.2 (1) | 7.4 (1.1) |

During followup, one tendon transfer failed as a result of the avulsion of the transferred tendon during the early postoperative period. This patient declined further treatment in our center.

Discussion

The transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon to the posterosuperior part of the rotator cuff for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears was described by Gerber et al. [9] in 1988 and since then has become a treatment option for this challenging condition. It may offer improved shoulder motion and function by creating a shoulder external rotator and forward flexor with the rerouting of a shoulder internal rotator and helps to avoid the superior migration of the humeral head, which may progress to rotator cuff arthropathy [5]. Latissimus dorsi transfer offers good functional results in the early and midterm postoperative periods [1, 6, 7]. However, the long-term durability of the functional improvement (tendon transfer effect) and the preservation of acromiohumeral distance (tenodesis effect) are still open to debate. We therefore assessed the functional outcomes (shoulder FE, ER, Constant-Murley score, ASES score, VAS pain score) and radiographic outcomes (acromiohumeral distance, cuff tear arthropathy) during a period of 3 years after latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears.

Limitations of this study are the small number of patients and relatively short followup; the latter is particularly important, because in some ways the benefits of the procedure were observed to diminish over time during this study. Longer followup clearly is called for. However, we maintained consistent, defined indications for using this procedure so that our results should be generalizable to the practices of others who are similarly facile with the procedure. Massive rotator cuff tears often involve several tendons, and it is important to note that inferior results have been reported by others when the function of the subscapularis muscle was also impaired [1, 6] and the teres minor muscle showed advanced fatty infiltration greater than Grade 2 [3, 17], but in all our patients, the subscapularis tendons were intact and the teres minor muscles had less than Grade 2 fatty infiltration, rendering our group optimal to study the pure effect of the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears without the interference of concomitant factors. One other limitation is that although the changes in the acromiohumeral distance values were found to be significant, the numbers were too small and should be supported by larger studies with a high inter- and intraobserver reliability. Another limitation of this study was the lack of advanced MRI studies to evaluate the integration of the transferred tendon to the proximal humerus and to associate the tenodesis effect solely to acromiohumeral distance changes.

We found increased shoulder FE and ER at 6-month followup and the results were preserved until the latest followup. Several studies have reported increases in shoulder motion with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears [1, 6, 7, 9, 14]. Gerber et al. [9] showed an increase in FE from 83° to 135° at a mean 33 months, whereas Aoki et al. [1] reported an increase from 99° to 135°. The restoration of the ER is also a main functional benefit of latissimus dorsi transfer, which is also used for children with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy [18]. Warner and Parsons [19] reported a mean 38° gain for ER in adduction in patients who underwent latissimus dorsi tendon transfer as the first intervention. Recently, Henseler et al. [13] reported a mean increase of 28° (from 23° to 51°) in ER in the adducted shoulder and a 60° increase (from 10° to 70°) in ER in the 90° abducted shoulder. In another recent study, Gerber et al. [7] showed that the improvements in shoulder motion did not deteriorate at a minimum of 10 years. Our results are comparable with these studies. Our gain for ER in adduction at the latest followup was less than those of the previous studies. We believe that the reason for this difference is the relatively higher preoperative ER in our patient group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4A–B.

Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer was able to obtain satisfactory (A) FE and (B) ER at the end of the second year.

We noticed an increase in Constant-Murley scores in our patients in the early postoperative period, which remained relatively unchanged until the latest followup. Increases in Constant-Murley scores have been widely reported after the transfer of the latissimus dorsi for massive rotator cuff tears [1, 7, 13, 15, 19]. In addition, we found an increase in ASES scores at the 6-month evaluation. However, at the latest evaluation, the ASES scores decreased from the 6-month values but still remained higher than the preoperative values. We speculate that an increase in pain might be the reason behind the decrease in the ASES scores at latest followup, because the ASES score is driven largely by pain.

Pain relief is another commonly reported gain with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive rotator cuff tears [2, 10, 13, 20, 21]. Henseler et al. [13] showed a 3.2-point decrease in mean VAS scores in seven patients 1 year after the tendon transfer. In their study with a mean followup of 28 months, Zafra et al. [21] reported pain relief in 88.8% of patients. Gerhardt et al. [10] demonstrated an improvement in pain parameters of the Constant-Murley score at the end of 2 years, which were found to be decreased slightly at the end of the fifth year. Our patients also benefited from the surgery in terms of pain relief both in the early and midterm postoperative periods. However, this improvement showed a decrease as the followup time increased. We speculate that the loss of the tenodesis effect, which causes a decrease in midterm acromiohumeral distances relative to the early postoperative values, might lead to the progression of arthropathy, even if this progression was not visible on plain radiographs in our patients.

The increase in acromiohumeral distance in neutral rotation in the early postoperative period did not last until the latest followup. We believe that latissimus dorsi transfer to a more proximal point on the humeral head creates a strong downward pull force that is enough to increase the acromiohumeral distance during the early postoperative period. Similarly, Henseler et al. [13] demonstrated by electromyography studies that in addition to the tenodesis effect, latissimus dorsi tendon transfer had a transfer effect. They reported favorable results at the end of the first year [13]. However, at the latest followup, we saw an increased acromiohumeral distance. We speculate that the transferred tendon adapted to stretching with elongation of the muscle-tendon unit, which diminished the tenodesis effect (Fig. 5). Gerber et al. [8] showed a mean 2.5-mm decrease in the acromiohumeral distance after a mean followup of 147 months. Similarly, with a longer followup, the decrease in acromiohumeral distance we saw between the early and midterm postoperative period may worsen and may become narrower than the preoperative values.

Fig. 5A–B.

(A) Acromiohumeral distance was found to be widened at the 6-month followup. (B) However, at the latest followup, the humeral head translated superiorly as a result of the loss of the tenodesis effect. Although reverse shoulder arthroplasty is a salvage procedure for massive cuff tears with advanced arthropathy, long-term results of this treatment are not yet available to any large degree, and how patients with reverse shoulder arthroplasties may fare when those reconstructions fail is unknown. The latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may improve shoulder functions in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. However, because the tenodesis effect loses its strength with time, progression of the arthropathy should be expected after a certain period. Nevertheless, latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may help to delay the need for reverse shoulder arthroplasty for these patients.

Previous reports have shown that latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears helps to prevent the progression of cuff tear arthropathy [5, 21]. In our patient group, all but one patient remained Grade 1 according to the Hamada classification throughout the followup period. This patient was considered an early failure and advanced arthropathy was found at latest followup. Although reverse shoulder arthroplasty was proposed, the patient refused any further treatment. In their study with 10-year followup, Gerber et al. [8] found slow progression of arthropathy at the latest followup. However, this does not necessarily imply that those patients have a poor functional status. Both in our study and in the study of Gerber et al. [8], functional improvement in the patients did not worsen significantly during the midterm and late postoperative period despite arthropathy progression and decrease in the acromiohumeral distance.

Although reverse shoulder arthroplasty is a salvage procedure for massive cuff tears with advanced arthropathy, long-term results of this treatment are not yet available to any large degree, and how patients with reverse shoulder arthroplasties may fare when those reconstructions fail is unknown. The latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may improve shoulder functions in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. However, because the tenodesis effect loses its strength with time, progression of the arthropathy should be expected after a certain period. Nevertheless, latissimus dorsi tendon transfer may help to delay the need for reverse shoulder arthroplasty for these patients.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey.

References

- 1.Aoki M, Okamura K, Fukushima S, Takahashi T, Ogino T. Transfer of latissimus dorsi for irreparable rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:761–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmingham PM, Neviaser RJ. Outcome of latissimus dorsi transfer as a salvage procedure for failed rotator cuff repair with loss of elevation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:871–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costouros JG, Espinosa N, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Teres minor integrity predicts outcome of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake GN, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB. Indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1526–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favard L, Levigne C, Nerot C, Gerber C, De Wilde L, Mole D. Reverse prostheses in arthropathies with cuff tear: are survivorship and function maintained over time? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2469–2475. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1833-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber C, Rahm SA, Catanzaro S, Farshad M, Moor BK. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for treatment of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: long-term results at a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1920–1926. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerhardt C, Lehmann L, Lichtenberg S, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Modified L’Episcopo tendon transfers for irreparable rotator cuff tears: 5-year follow-up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1572–1577. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears: a long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamada K, Yamanaka K, Uchiyama Y, Mikasa T, Mikasa M. A radiographic classification of massive rotator cuff tear arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2452–2460. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1896-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henseler JF, Nagels J, Nelissen RG, de Groot JH. Does the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive rotator cuff tears remain active postoperatively and restore active external rotation? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irlenbusch U, Bracht M, Gansen HK, Lorenz U, Thiel J. Latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenberg S, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Are there advantages of the combined latissimus-dorsi transfer according to L’Episcopo compared to the isolated latissimus-dorsi transfer according to Herzberg after a mean follow-up of 6 years? A matched-pair analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1499–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melis B, DeFranco MJ, Chuinard C, Walch G. Natural history of fatty infiltration and atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle in rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1498–1505. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh JH, Kim SH, Choi JA, Kim Y, Oh CH. Reliability of the grading system for fatty degeneration of rotator cuff muscles. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1558–1564. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozben H, Atalar AC, Bilsel K, Demirhan M. Transfer of latissmus dorsi and teres major tendons without subscapularis release for the treatment of obstetrical brachial plexus palsy sequela. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:1265–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner JJ, Parsons IM., 4th Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer: a comparative analysis of primary and salvage reconstruction of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:514–521. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.118629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weening AA, Willems WJ. Latissimus dorsi transfer for treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1239–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-0970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zafra M, Carpintero P, Carrasco C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2009;33:457–462. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0536-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]