Abstract

Background

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is caused by an anatomic deviation of the acetabular rim or proximal femur, which causes chronic groin pain. Radiological identification of FAI can be challenging. Advances in imaging techniques with the use of computed tomography (CT) scan enable 3D simulation of FAI. We made an experimental cadaveric validation study to validate the 3D simulation imaging software.

Methods

The range of motion (ROM) of five cadaveric hips was measured using an electromagnetic tracking system (EMTS). Specific marked spots in the femur and pelvis were created as reproducible EMTS registration points. Reproducible motions were measured. Hips were subsequently imaged using high-resolution CT after introduction of artificial cam deformities. A proprietary software tool was used, Articulis (Clinical Graphics) to simulate the ROM during the presence and absence of the induced cam deformities.

Results

According to the EMTS, 13 of the 30 measured ROM end-points were restricted by > 5° due to the induced cam deformities. Using Articulis, with the same 5° threshold, we correctly detected 12 of these 13 end point limitations and detected no false positives. The median error of the measured limitations was 1.9° (interquartile range 1.1° - 4.4°). The maximum absolute error was 5.4°.

Conclusions

The use of this dynamic simulation software to determine the presence of motion limiting deformities of the femoroacetabular is validated. The simulation software is able to non-invasively detect a reduction in achievable ROM, caused by a cam type deformity.

Keywords: Femoroacetabular impingement, Diagnostics, CT, Dynamic

Background

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is an accepted etiology of premature osteoarthritis of the non-dysplastic hip [1]. It has predominance for males, with a prevalence of 17% in men and 4% in women [2,3]. FAI caused by a cam or pincer deformity can be treated by open dislocation and osteotomy, mini-open procedure or by an arthroscopic resection of the bony deformity. All methods are effective at reducing pain, improving function and are relatively save. The arthroscopic method has a lower complication rate and functional results of this procedure have been described as good [4-7]. Also, a high return to pre-injury levels of sports performance in athletes has been described [8]. However, not all patients recover as to be expected, and revision of the arthroscopy may be needed in these cases. Persistent bony impingement due to residual or untreated bone deformity of the hip and underlying osteoarthritis have been described as the most frequent causes of revision arthroscopy, up to 95% [9-11] It is, therefore, of paramount importance to diagnose the exact position of the deformity causing the impingement. Plain radiography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used in the common diagnostic work-up of FAI. Despite this variety of radiological modalities, it remains a challenge to comprehensively evaluate the FAI associated deformities and, thus, to create a complete resection of the FAI. Several authors have pointed out the inefficacy of the current morphological parameters on plain radiographs [12-15]. We still lack methods to determine whether a deformity impinges during movements of a patient. Evaluation by clinicians remains an important part of diagnosing FAI [16]. Dynamic evaluation can be helpful in determining whether impingement occurs.

Recent advances in 3D imaging enable simulation of range of motion (ROM) of joints in patients [17]. By converting image data to virtual 3D models of the femur and the pelvis, it is possible so simulate the dynamic function of a hip joint. Used in conjunction with the clinical examination of the hip joint, these motion simulations may confirm whether groin pain is attributable to morphological characteristics of the joint [18].

The aim of this study was to validate a CT-based motion simulation software method that has already been validated for other joints [16,19], in the context of FAI, and to evaluate the method’s applicability for the diagnostic work-up of FAI in a prospective cohort follow-up study of FAI patients. Although this software has perfect repeatability, it is no golden standard for measurement of range of motion. For this purpose, we determined its accuracy in a range of motion assessment study of five human cadavers. We hypothesized that the software is a reliable measurement tool to detect a reduction in achievable ROM caused by a cam type deformity.

Methods

Five human cadaveric hip joints from three individuals who had donated their bodies to science (two female, one male) were available from the Department of Anatomy (institution blinded). All anatomic specimens were prepared with Anubifix™ (city blinded, the Netherlands) for optimal preservation [20] and selected for absence of obesity, lack of a total hip arthroplasty and an optimal flexibility of the hip joint of at least 90° of flexion. Gender or age was no selection criteria.

In order to expose the hip joint and to maintain stability and flexibility all the cadaveric hip joints were prepared with the anterolateral approach according to Hueter [21] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The positioning of the cadaver in supine position with the Kirschner-wires in position. Next to the left foot is the main device of the EMTS.

Measurements of the range of motion of the hips were acquired using the electromagnetic tracking system [22] (EMTS), (Flock of Birds, Ascension Technology, United States). This system uses a magnetic field to determine the position and orientation of the sensors to its transmitter. The system requires reproducible registration points on the hip and the femur, according to the ISB recommendations coordinate system. Kirchner-wires were attached into every specimen on marked locations: two K-wires, three centimeters apart, were positioned into the superior anterior iliac spine as registration points for the pelvis. One K-wire was attached into the greater trochanter and one in each epicondyles of the knee as the registration points of the femur (Figure 2). The sensors were attached to the K-wires, as close to the skin as possible. A final sensor was attached to a pointer that registered the other sensors. As per the guidelines of Milne [23], optimal range between the transmitter and the sensors should be between 22.5 and 64.0 cm. All specimens were prepared and measured on a plastic table and all metal objects within a range of one meter were removed to prevent interference with the magnetic signal.

Figure 2.

The position of the K-wires in the specimen.

We registered the maximum flexion, abduction, internal rotation at 0°, 30°, 60° and 90° of flexion. Any positional and rotational changes of respectively 0.25 mm and 0.1° were determined. We measured all end points twice and all differences were < 2%.

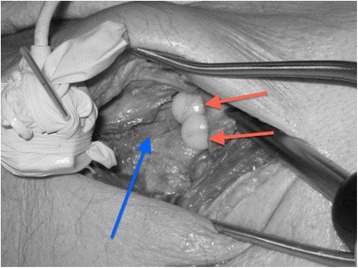

An artificial cam deformity was created using nylon screws with a diameter of 1 cm and a thickness of 3.5 mm (Figure 3). Nylon was used because it is known not to interfere with the EMTS while it provides sufficient contrast on the CT images. The density of nylon is less than human bone: 1.15 g/cm3 vs. 1.9 g/cm3 respectively, and can be distinguished from bone and surrounding soft tissues. Two screws were inserted on the anterio-superior position of the femoral head, between the 11 and 2 ‘o clock-position in full extension and neutral position of the hip [24,25]. After insertion of the screws, the exact same measurements were taken as before. As the simulation software does not take into account the soft tissues of the joint and thus over-estimated the range of motion of each hip joint by default, we chose not to assess the absolute range of motion but the relative change in range of motion as a result of an introduced cam deformity.

Figure 3.

Artificial cam deformity created by nylon screws (red arrow pointing at the screws) inserted at the anterio-superior position of the head-neck junction, after preparation with the Hueter approach. The blue arrow points at the collum of the femur.

The specimens were subsequently imaged by means of non-contrast CT scan. CT scan was performed in the Department of Radiology, (institution blinded), using a second generation dual source multidetector spiral CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare AG, Erlangen, Germany) with a tube voltage of 80 kV and an effective mAs-value of 3,140. Scan time per CT scan was approximately 30 seconds. All specimens were scanned in the standard anatomic axial plane orientation and were reconstructed with an effective slice thickness of 1.0 mm and a sharp reconstruction kernel (B75s). Multi-planar reconstruction was performed (image pixel size 0.265 mm).

We used the software package Articulis (institution blinded, city blinded, the Netherlands) to simulate the ROM of the hip joints. The software used the introduced k-wires as registration points, so that the measurements were exactly reproducible between the CT-model and the specimens. The software then automatically converts the CT scans to 3-Dimensional models of the femur and the pelvises. For each hip joint, two different versions of the femur were created: one with and one without the artificially induced cam deformities. The software identifies the impinging area by 0.1 mm and calculates the amount of bone necessary to resect and dissolve the impingement.

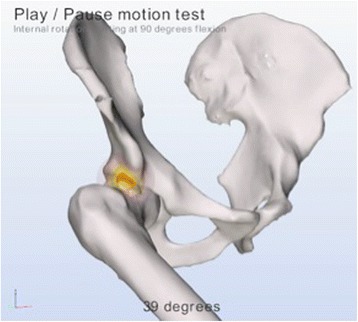

Articulis uses the coordinate systems as described in the Recommendations of the International Society of Biomechanics [26] and the equidistant method described by Puls et al. in [27]. Flexion refers to elevation parallel to the sagittal plane along the Z-axis of the pelvis. Abduction refers to elevation in the coronal plane along the X-axis of the pelvis and internal rotations refer to axial rotation along the femur shaft of Y-axis of the femur. The software systematically simulates different motions, for example flexion, abduction, internal rotations with 90° flexion. While reorienting the femur model the software checks for collisions of the bone models. Up to 3 mm of translation of the femoral head is allowed, applied when reorienting the femur leads to collisions. When more than 3 mm of translation is required to reach a collision free state, simulation is halted and the angle at which impingement occurred is registered. Figures 4 and 5 are simulations as provided by the software of a cam deformity causing impingement during simulated internal rotation.

Figure 4.

A simulation of the artificial cam deformity by the software with the hip in extension: the cam deformity is clearly visible at the anterio-superior position at the head-neck edge.

Figure 5.

A simulation of internal rotation made by the software, which detects an impingement of the cam deformity with the acetabulum and therefor limiting the internal rotation.

No ethics approval was obliged for this cadaveric validation study.

Statistical analysis

We compared the motion limitations observed with the EMTS to the motion limitations determined by the Articulis ROM simulation software. The median deviation, interquartile range and the maximum absolute deviation of the differences were calculated. For these calculations the measurements of the five cadaveric hip joints were combined. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistic 20 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

According to the EMTS, 13 of the 30 measured ROM end points were restricted by more than 5° due to the induced cam deformities. Using Articulis and with the same 5° threshold, we correctly detected 12 of these 13 end point limitations and detected no false positives. The median error of the simulated ROM limitations compared to the EMTS measured limitations was 1.9° (interquartile range 1.1° - 4.4°). The maximum absolute error was 5.4°. Table 1 is an example of our measurements of a cadaveric hip joint. Table 2 summarized all measurements.

Table 1.

Example of comparison measurements software vs. EMTS of hip joint 5

| Simulations | EMTS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Cam | Cam | Difference | No Cam | Cam | Difference | Difference of the difference | |

| Max flexion | 105 | 93 | 12 | 110 | 93 | 16 | −4 |

| Max abduction | 29 | 31 | 0 | 35 | 34 | 1 | −1 |

| Max internal rotation | 60 | 60 | 0 | 38 | 37 | 1 | −1 |

| Max internal rotation at 30° | 34 | 34 | 0 | 32 | 34 | −2 | 2 |

| Max internal rotation at 60° | 27 | 26 | 0 | 37 | 31 | 6 | −5 |

| Max internal rotation at 90° | 20 | 1 | 19 | 32 | 18 | 14 | 5 |

Table 2.

Difference in degrees between the true limitation (measured with EMTS) and the limitation detected by the simulation software

| Hip joint | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ci | R | R | L | R | L | Median |

| Max flexion | −2 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −4 | −1.7 |

| Max abduction | −1 | 0 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −0.5 |

| Max internal rotation | 0 | 3 | −7 | −2 | −1 | −0.8 |

| Max internal rotation at 30° | 0 | −1 | 2 | −1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Max internal rotation at 60° | −1 | −1 | 5 | −2 | −5 | −1.3 |

| Max internal rotation at 90° | 02 | 1 | 0 | −3 | 5 | 0.0 |

Discussion

In this cadaveric study we evaluated the presence of motion limiting deformities of the femoroacetabular joint by non-invasive modeling software, using 3D radiological imaging. We correctly detected 12 of the 13 end point limitations compared to the EMTS as the gold standard for measurements of ROM. The one hip that we could not correctly detect was mainly limited by soft tissue problems of the hip, which totally limited the internal rotation in neutral position. With a median error of only 1.9°, we can consider the software a highly reliable measuring tool.

Based on our study, we consider this CT-based motion simulation software as validated in the context of measuring the ROM of a hip joint that are limited by FAI deformities.

We chose a 5° threshold to evaluate if the software could detect such a limitation. A 5° threshold is fare above the measurement error (1,9°) of the software. We don’t state that this 5° limitation also is a significant limitation of the motion of the hip. This amount is only set to evaluate the accurateness of the software in detecting changes in the range of motion caused by an impinging deformity.

The use of cadaveric hip joints has its limitations and disadvantages. All specimens were prepared with AnubifixTM for optimal preservation [20]. Despite being optimally preserved, joints flexibility or ROM is not identical as in a living human. The use of specimens was inevitable to be able to prepare a standardized artificial cam deformity in the hip joint. By creating the cam deformity, we had exact information about the size and position of the deformity. This knowledge provided us with an accurate ground truth to compare our simulations against. We consider our method of comparing our standardized measurements of the deformities to their exact parameters as very accurate. The expected limited ROM of the cadavers did not influence our measurements, as the movements of the hips during our measurements were not limited by stiffness of the soft tissues of the cadavers.

Our purpose was to determine whether the simulations of the software could accurately determine ROM as encountered in physical examinations. We used the EMTS “Flock of Birds” system as a gold standard for the measurement of movement and angulation. This system has been calibrated and validated for many applications in motion measurements. Comparing the angles of the ROM with and without an impinging cam-type deformity of both methods demonstrates that the software correctly assesses ROM.

To compare the measurements of the software to the movements of the hip in real life, during sports-activities for example, was not the goal of this study. Our goal was to determine whether the measurement were reliable and valid. The software is able to determine every kind of range of motion possible in the joint. We didn't measure complicated combined angles, which are needed in real life sports like field hockey or soccer, because our specimen weren’t able to provide such range of motion. This is a limitation of our study and due to the specimen we used. If we had determined what kind of combined movements the hip joint makes during sports, than the software should be able to reproduce these combined movements. However, if the hip joint is limited at the ranges we measured, then it would probably also be limited during sports which requires a larger free range of motion.

Visualization of the cam deformity causing a FAI is challenging. Plain radiography with measurement of alpha angles as well as high resolution and multiplanar CT are widely used. Because of the dynamic aspect of FAI it is nearly impossible to detect the exact impinging location on a two dimensional image. Although Barton et al. [28] and Nepple et al. [29] state that the use of the alpha angle in the evaluation of cam-type FAI is validated, the use of CT scans adds an essential third dimension. But even in this gold standard for diagnostics, the dynamic aspect remains neglected. Several authors support this flaw of the alpha angle measurement [12-15]. Also, a recent study by de Bruin et al. [30] describes a very high prevalence of radiographic signs of FAI at all ages in an asymptomatic population (up to 86.59%). This emphasizes the importance of a simulated analysis based on these radiographic images or direct kinematics analysis.

CT scans have the disadvantage of ionizing radiation. The appropriateness of the use of CT scans should therefore always be evaluated. Accurate diagnosing could, however, limit the amount of unsuccessful operations and revision arthroscopies of the hip joint for FAI. We believe that the use of non-contrast based CT scans for diagnosing FAI is acceptable because there is currently no true alternative. Low dose reduction techniques and, as described by Gervaise in 2013 [31] and low dose protocols as described by Becce et al. in 2013 [32], might be solutions for these radiation problems. Further research in this area must point out if these alterations compromise the quality of possible dynamic analyses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has the potential to be a good alternative, as it does not involve radiation. MRI is, however, more challenging for three-dimensional simulation of the joints due to a lower spatial resolution and less accurate delineation of bone compared to CT with most MRI pulse sequences. Besides image acquisition with MRI requires more time than for CT.

The validation of this software opens up the possibility to use dynamic motion simulation based on CT scans in the diagnostic pathway or FAI. We hypothesize that creating a dynamic model will result in better functional outcomes in patients with FAI compared to those in previous studies. Described functional outcome results of FAI treated by hip arthroscopy are good [4,7]. The rate of unsuccessful surgeries and revision-surgeries could be diminished due to better visualization of the deformity causing the impingement. This hypothesis is currently under investigation by adding the CT movement analysis to our diagnostic work-up for FAI in the off setting of our prospective cohort, which is currently under analysis.

Conclusions

This cadaveric study evaluated the use of software to determine the presence of motion limiting deformities of the femoroacetabular joint using radiological imaging with CT. To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate a non-invasive dynamic simulation on pre- and post-operative scenarios representing cam type deformities. The simulation software is able to non-invasively detect a reduction in achievable ROM, caused by a cam type deformity. This technique shows promise as a clinically diagnostic tool for FAI diagnostics and for preoperative planning.

Acknowledgements

Peter Krekel, TU Delft, the Netherlands, for providing the software and hardware of Flock of Birds. No source of funding to declare.

Abbreviations

- FAI

Femoroacetabular impingement

- CT

Computed tomography

- ROM

R of motion

- EMTS

Electromagnetic tracking system

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

Edwin HG Oei, Peter Pilotm, Gert-Jan Kleinrensink and Rolf M Bloem contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MAR, MD. First author, main contributor of study design, experiments, data analysis and manuscript preparation. MIV MD Had major participation in study design, experiments and manuscript preparation. EHGO, MD PhD. Head of radiology department, important role in experiments and revision of manuscript. PP PhD. Senior research member, approvel of study design, important part of manuscript preparation and revision. GJK PhD. Head of department of Anatomy, essential for experiments on cadaver samples. RMB MD PhD. Head of department of Orthopaedic surgery, significant contribution to study design and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Maarten A Röling, Email: roling@rdgg.nl.

Monique I Visser, Email: moniquingeborg@hotmail.com.

Edwin HG Oei, Email: e.oei@erasmusmc.nl.

Peter Pilot, Email: pilot@rdgg.nl.

Gert-Jan Kleinrensink, Email: g.kleinrensink@erasmusmc.nl.

Rolf M Bloem, Email: bloem@rdgg.nl.

References

- 1.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. “The Etiology of Osteoarthritis of the Hip. An integrated mechanical concept” Symposium: papers presented at the annual closed meeting of the international hip society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:264–72. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrd J, Jones K. Hip arthroscopy in athletes: 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;11(37):2140–3. doi: 10.1177/0363546509337705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hack K, Primio G, Rakhra K. Prevalence of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement morphology in asymptomatic volunteers. J Bone Joint Surg. 2010;14(92):2436–44. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aprato A.; Jayasekera N.; Viaal RN. Revision hip arthroscopic surgery: outcome at three years. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013; Jan 18, doi:10.1007/s001670-013-2373-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ilizaliturri V. Complications of arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement treatment: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):760–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0618-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda DK, Carlisle JC, Arthurs SC, Wierks CH, Philippon MJ. Comparative systematic review of the open dislocation, mini-open, and arthroscopic surgeries for femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):252–69. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris JD, Erickson BJ, Bush-Joseph CA, Nho SJ. Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. Curr Rev Muscoloskelet Med. 2013;6:207–18. doi: 10.1007/s12178-013-9172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alradwan H, Philippon MJ, Farrokhyar F, Phil M, Chu R, Whelan D, et al. Return to Preinjury Activity Levels After Surgical Management of Femoroacetabular Impingement in Athletes. Systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1567–76. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogunovic L, Gottlieb M, Pashos G, Bac G, Clohisy JS. Why do hip arthroscopy procedures fail? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(8):2523–9.rr. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyworth BE, Shindle MK, Voos JE, Rukzki JR, Kelly BT. Radiologic and intraoperative findings in revision hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Kuppersmith DA, Maxwell RB, Stubbs AJ. Revision hip arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1918–21. doi: 10.1177/0363546507305097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer WE. Femoroacetabular impingement: caution is warranted in making imging-based assumptions and diagnosis. Radiology. 2010;257:4–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin DA. Femoroacetabular impingement: fact, fiction or fantasy? AJR. 2013;201:526–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutter R, Dietrich TJ, Zingg PO, Pfirrmann CWA. How useful is the alpha angle for discriminationg between symptomatic patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement and asymptomatic volunteers? Radiology. 2012;264:514–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepage-Saucier M, Thiéry C, Larbi A, Lecouvet FE, Vand Berg BC, Omoumi P. Femoroacetabular impingement: normal values of the quantitative morphometric parameters in asymptomatic hips. Eur Radiol. 2014;7:1707–14. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reurink G, Jansen SPL, Bisselink JM, Vincken PWJ, Weir A, Moen MH. Reliability and validity of diagnosing acetabular labral lesions with magnetic resonance arthrography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1643–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krekel PR, Botha CP, Vastart ER, de Bruik RW, Rozing PM, Post FH. “Interactive simulation and comparative visualisation of the bone-determinded range of motion of the human shoulder”. Proc Simulation Visualization. 2006;3:275–88. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krekel PR, Vochteloo AJ, Bloem RM, Nelissen RG. Femoroacetabular impingement and its implications on range of motion: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:143. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vochteloo AJ, Krekel PR, vd. Sande MA, Nagels J. Range of motion implications of proximal humerus fractures: a case study. Eur Orthop Traumatol. 2011;2(56):153–6. doi: 10.1007/s12570-011-0080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slieker J, Theeuwes HP, Rooijen GL, Van Lange JF, Kleinrensink GJ. Training in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a new educational model using specially embalmed human anatomical specimen. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(8):2189–94. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2158-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rachbauer F, Kain MS, Leunig M. The history of the anterior approach to the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meskers CG, Fraterman H, Vd Helm FC, Vermeulen HM, Rozing PM. Calibration of the “Flock of Birds” electromagnetic tracking device and its applications in shoulder motion studies. J Biomech. 1999;32(6):629–33. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milne AD, Chess DG, Johnson JA, King GJW. Accuracy of an electromagnetic tracking device: a study of the optimal operating range and metal interference. J Biomech. 1996;29(6):791–3. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)83335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Boint Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87:1012–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannast M, Goricki D, Beck M, Murphy SB, Siebenrock KA. Hip damage occurs at the zone of femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(2):273–80. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0061-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu G, Siegler S, Allard P, Kirtley C, Leardini A, Rosenbaum D, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate system of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion - part I: ankle, hip, and spine. J Biomech. 2002;35:543–8. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puls M, Echer TM, Tannast M, Steppacker SD, Siebenrock KA, Kowal JH. The equidistant method – a novel hip joint simulation algorithm for detection of femoroacetabular impingement. Comput Aided Surg. 2010;15(4–6):75–82. doi: 10.3109/10929088.2010.530076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton C, Salineros MJ, Rakhra KS, Beaulé PE. Validity of the alpha angle measurement on plain radiographs in the evaluation of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(2):464–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nepple JJ, Martel JM, Kim YJ, Zaltz I, Clohisy JC. Anchor study group. Do plain radiographs correlate with CT for imaging of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3313–20. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2510-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Bruin F, Reijnierse M, Farhang-Razi V, Bloem JL. Radiographic signs associated with femoroacetabular impingement occur with high prevalence at all ages in a hospital population. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(11):3131–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2912-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gervaise A, Osemont B, Louis M, Lecocq S, Teixeira P, Blum A. Standard dose versus low-dose abdominal and pelvic CT: comparison between filtered back projection versus adaptive iterative dose reduction 3D. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becce F, Ben Salah Y, Verdun FR, Vande Berg BC, Lecouvet FE, Leuli R, et al. Computed tomography of the cervical spine: comparison of image quality between a standard-dose and a low-dose protocol using filtered back-projection and iterative reconstruction. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(7):937–45. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]