Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with multiple comorbid conditions, such as asthma and food allergy. We sought to determine the impact of eczema severity on the development of these disorders and other non-atopic comorbidities in AD.

Methods

We used the 2007 National Survey of Children's Health, a prospective questionnaire-based study of a nationally representative sample of 91,642 children age 0-17 years. Prevalence and severity of eczema, asthma, hay fever and food allergy, sleep impairment, healthcare utilization, recurrent ear infections, visual and dental problems were determined.

Results

In general, more severe eczema correlated with poorer overall health, impaired sleep and increased healthcare utilization, including seeing a specialist, compared to children with mild or moderate disease (Rao-Scott Chi-square, P<0.0001). Severe eczema was associated with higher prevalence of comorbid chronic health disorders, including asthma, hay fever and food allergies (P<0.0001). In addition, the severity of eczema was directly related to the severity of the comorbidities. These associations remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models that included age, sex and race/ethnicity. Severe eczema was also associated with recent dental problems, including bleeding gums (P<0.0001), toothache (P=0.0004), but not broken teeth (P=0.04) or tooth decay (P=0.13).

Conclusions

These data indicate that severe eczema is associated with multiple comorbid chronic health disorders, impaired overall health and increased healthcare utilization. Further, these data suggest that children with eczema are at risk for decreased oral health. Future studies are warranted to verify this novel association.

Keywords: eczema prevalence, eczema severity, atopic dermatitis, asthma, atopic, rhinoconjunctivitis, hay fever, food allergies, comorbidities, healthcare utilization, epidemiology

Introduction

There is a dearth of population-based studies of comorbidities in eczema and most of the existing data come from European studies. Moreover, prevalence estimates for comorbid atopic disorders, e.g. asthma, vary greatly because of limitations inherent to smaller non-population based studies with various designs. Thus, US-population based estimates of the prevalence of both atopic and non-atopic comorbidities are invaluable for developing a comprehensive approach to the management of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Besnier was reportedly the first to describe the association of AD with allergic rhinitis and asthma (1). The association between AD and other atopic disorders is now well established. However, US population-based estimates for the comorbid disease burden in AD are lacking. Further, little is known about other non-atopic comorbidities in AD. We hypothesized that AD, especially severe disease, is associated with more comorbid medical disorders and increased healthcare utilization. Several in vitro, animal model and human genetic studies found aberrant toll-like receptor signaling and innate immunity in AD (reviewed in 2). Such aberrancies would likely predispose to both cutaneous and extra-cutaneous infections. We hypothesized that AD is associated with increased susceptibility to extra-cutaneous infections, including ear infections and oral infections resulting in dental problems. In the present study, we present a comprehensive analysis of atopic and non-atopic comorbid disorders in AD.

Methods

National Survey of children's Health (NSCH)

We used data from the 2007-2008 NSCH survey of 91,642 households, which was designed to estimate the prevalence of various child health issues including physical, emotional, and behavioral factors. NSCH was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services with a goal of >1,700 households per state. The National Center for Health Statistics conducted the study using the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey (SLAITS) program. The telephone numbers were chosen at random, followed by identification of the households with one or more children under the age of 18. Subsequently, one child was randomly selected for interview. The survey results were weighted to represent the population of non-institutionalized children nationally and in each state. Using the data from U.S. Bureau of the Census, weights were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, household size, and educational attainment of the most educated household member to provide a dataset that was more representative of each state's population of non-institutionalized children less than 18 years of age as previously described (3). The National Center for Health Statistics of Center for Diseases Control and Prevention oversaw sampling and telephone interviews. Approval by the institutional review board was waived.

Eczema prevalence

AD/eczema was determined using the NSCH question, “During the past 12 months, have you been told by a doctor or other health professional that (child) had eczema or any kind of skin allergy?” To limit the effect healthcare access may have on the results, we excluded all subjects who responded “no” or “don't know” to the question, “During the past 12 months, did (child) see a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional for any kind of medical care, including sick-child care, well-child check-ups, physical exams, and hospitalizations?”

Eczema severity

Severity of AD/eczema was determined using the NSCH question, “Would you describe (child's) eczema or skin allergy as mild, moderate, or severe?” To limit the effect healthcare access may have on the results, we excluded all subjects who responded “no” or “don't know” to having eczema in the past 12 months. Responses were encoded as an ordinal variable, where 1=mild, 2=moderate and 3=severe.

Comorbidities

The prevalence and severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergies, recurrent ear infections, visual and dental problems, as well as overall health, impaired sleep, requirement of more services than other children of the same age, and being seen by a specialist were determined by survey responses (questions presented in supplemental Table 1). Non-responders or “not known” responses were considered as missing data. Number of chronic health conditions and services used are derived variables from the NSCH, which represent the sum of all medical conditions and services elicited in the survey, respectively.

Data processing and statistical methods

All data processing and statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.2. Analyses of survey responses were performed using SURVEY procedures. Univariate associations were tested by Rao-Scott chi-square tests (SURVEYFREQ). Multivariate logistic regression models were constructed that included age and race/ethnicity due to potential confounding and sex due to significant effect medication (SURVEYLOGISTIC). Analysis of eczema severity was performed by dichotomizing responses into mild/moderate versus severe eczema. This approach was used over ordinal logistic regressions because the data did not meet the proportional odds assumption (Score test, P<0.01). Complete data analysis was performed, i.e. subjects with missing data were excluded. Linear interactions were tested in logistic regression models and included in final models if P-values were <0.05.

Correction for multiple dependent tests (k=44) with the approaches of Benjamini and Hochberg (4) yielded critical P-values of 0.015. Thus, a two-sided P-value <0.015 was taken to indicate statistical significance for all estimates.

Results

Eczema prevalence and severity

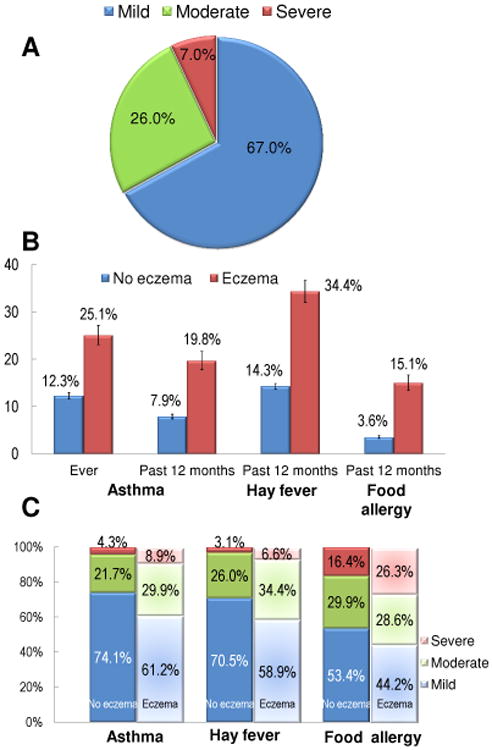

Subject demographics are presented in Table 1. There were 79,667 subjects with healthcare interaction in the previous year. Eczema prevalence was 12.97% (95% CI=12.42–13.53). Sixty seven percent (95% CI: 64.8–69.2) of children with eczema reportedly had mild, 26.0% (95% CI: 23.9–28.1) moderate and 7.0% (95% CI: 5.8–8.3) severe disease (Fig 1A).

Table 1. Subject characteristics (n=79,667).

| Variable | No eczema | Eczema | P-value# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) – mean (95% CI) | 8.4 (8.3–8.5) | 7.5 (7.3–7.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity – no. (%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| African-American | 6495 (13.5) | 1618 (22.2) | |

| Hispanic | 8582 (20.4) | 1215 (15.6) | |

| White | 46777 (57.1) | 6326 (52.5) | |

| Other/mixed | 6186 (9.0) | 1079 (9.7) | |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 33165 (48.3) | 5016 (49.8) | 0.25 |

| Household income (Poverty level) – no. (%) | 0.76 | ||

| 0 – 99% | 8023 (18.2) | 1253 (17.5) | |

| 100 – 199% | 11356 (20.4) | 1756 (20.4) | |

| 200 – 399% | 22966 (30.9) | 3478 (32.0) | |

| ≥400% | 26835 (30.5) | 3921 (30.1) |

Rao-Scott chi square test.

Parental refusal to answer a particular question or response of “don't know” occurred for the questions pertaining to eczema in 79 (0.1%), age in 0 (0.0%), race/ethnicity in 76 (0.1%), sex in 92 (0.2%), and household income in 0 (0.0%), respectively.

Figure 1. Association of childhood eczema prevalence and severity with comorbid atopic disease.

(A) Distribution of eczema severity. Eczema severity was divided into mild, moderate or severe. Data are presented as the percent (95% CI) of subjects who responded yes to having been told by a doctor to have eczema in the past 12 months. (B) Association of childhood eczema with comorbid atopic disease. Prevalence of ever asthma as well as asthma, allergic rhinitis and food allergies within the past 12 months was compared between eczema vs. no eczema. Data are presented as the percent (95% CI) of subjects who responded yes or no to having been told by a doctor to have eczema in the past 12 months, respectively. (C) Association of eczema with severity of comorbid atopic disease. Severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis and food allergies was divided into mild, moderate or severe. Data are presented as the percent (95% CI) of subjects who responded yes to having been told by a doctor to have eczema in the past 12 months.

Comorbid atopic disease

Overall, children with eczema reported a higher prevalence of comorbid atopic disease. Having eczema within the past 12 months was associated with higher prevalence [95% CI] of ever asthma (eczema vs. no eczema: 25.1% [23.1 – 27.2%] vs. 12.3% [11.7 – 13.0%]; Rao-Scott chi-square, P<0.0001), asthma within the past 12 months (19.8% [17.8 – 21.7%] vs. 7.9% [7.4 – 8.4%]; P<0.0001) and increased asthma severity (severe asthma: 8.9% [5.9 – 11.9%] vs. 4.3% [2.8 – 5.8%]; P<0.0001) (Figs 1B and 1C). Similarly, eczema was associated with a higher prevalence of allergic rhinitis within the past 12 months (34.4% [32.1 – 36.7%] vs. 14.3% [13.7 – 14.9%]; P<0.0001) and increased allergic rhinitis severity (severe allergic rhinitis: 6.6% [5.0 – 8.2%] vs. 3.1% [2.4 – 3.7%]; P<0.0001) (Figs 1B and 1C). Eczema was also associated with an almost five-fold higher prevalence of reported food allergies within the past 12 months (15.1% [13.4 – 16.7%] vs. 3.6% [3.3 – 3.9%]; P<0.0001) and increased food allergy severity (severe food allergy: 26.3% [21.1 – 31.5%] vs. 16.4% [13.5 – 19.4%]; P<0.0001) (Figs 1B and 1C).

In addition, the severity of the skin disease directly correlated with the prevalence and severity of the atopic comorbidities. Severity of AD did not meet the proportional odds assumption (Score test, P < 0.01). Therefore, severity was dichotomized into severe vs mild-moderate and binary logistic regression was performed. Severe eczema was associated with a higher prevalence of ever asthma (severe eczema vs. mild–moderate eczema: 36.9% vs. 24.3%; P=0.002), asthma within the past 12 months (32.2% vs. 19.0%; P=0.0003) and increased asthma severity (severe asthma: 36.1% vs. 5.5%; P<0.0001) (Table 2). Severe eczema was likewise associated with an increased prevalence of severe allergic rhinitis (29.1% vs. 4.6%; P<0.0001), but not overall allergic rhinitis within the past 12 months (39.0% vs. 34.1%; P=0.26). In contrast, severe eczema was associated with both increased prevalence of food allergies within the past 12 months (27.0% vs. 14.1%; P<0.0001) and increased food allergy severity (severe food allergy: 48.6% vs. 23.3%; P<0.0001).

Table 2. Association between severe eczema and comorbid atopic disease.

| Comorbid atopic disease | Mild or moderate eczema | Severe eczema | P-value# | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Percent (95% CI) | Freq | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| Asthma | |||||

| Ever asthma | 2226 | 24.3 (22.3, 26.4) | 201 | 36.9 (28.5, 45.2) | 0.002 |

| Asthma within the past 12 months | 1705 | 19.0 (17.0, 20.9) | 169 | 32.2 (24.1, 40.2) | 0.0003 |

| Asthma severity | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mild | 1110 | 64.1 (58.3, 69.9) | 73 | 36.7 (23.9, 49.5) | |

| Moderate | 485 | 30.4 (24.7, 36.1) | 61 | 27.2 (16.2, 38.2) | |

| Severe | 108 | 5.5 (3.4, 7.6) | 35 | 36.1 (20.5, 51.7) | |

| Hay fever | |||||

| Hay fever within the past 12 months | 3252 | 34.1 (31.7, 36.5) | 253 | 39.0 (30.7, 47.3) | 0.26 |

| Hay fever severity | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mild | 2124 | 61.4 (56.7, 66.0) | 86 | 31.1 (21.6, 40.7) | |

| Moderate | 960 | 33.9 (29.2, 38.6) | 109 | 39.7 (28.9, 51.5) | |

| Severe | 162 | 4.6 (3.3, 5.9) | 57 | 29.1 (18.5, 39.7) | |

| Food allergies | |||||

| Food allergies within the past 12 months | 1436 | 14.1 (12.5, 15.7) | 157 | 27.0 (19.2, 34.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Food allergy severity | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mild | 660 | 47.9 (41.6, 54.2) | 35 | 18.1 (9.1, 27.1) | |

| Moderate | 421 | 28.0 (22.7, 33.3) | 60 | 32.5 (18.9, 46.0) | |

| Severe | 344 | 23.3 (18.2, 28.3) | 61 | 48.6 (31.8, 65.4) | |

Rao-Scott chi-square test

Parental refusal to answer a particular question or response of “don't know” occurred for the questions pertaining to eczema severity in 22 (0.2%), ever asthma in 104 (0.1%), current asthma in 107 (0.2%), asthma severity in 13 (0.3%), current hay fever in 154 (0.2%), hay fever severity in 49 (0.3%), current food allergy in 120 (0.2%) and food allergy severity in 30 (0.6%), respectively.

Note: The proportional odds assumption was not met (Score test, P<0.01). Therefore, ordinal logistic regression was not used. Rather, all analyses of severity used binary logistic regression on dichotomized severe vs. mild-moderate disease. However, similar results were obtained when severity was dichotomized moderate-severe vs. mild.

All of these associations with eczema prevalence (P<0.0001) and severe eczema (P≤0.002) remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models that included age, sex and race/ethnicity. Similar results were obtained in regression models where severity was dichotomized into moderate-severe vs. mild disease.

Health outcomes

Overall, eczema within the past 12 months was associated with a higher number of chronic health conditions (eczema vs. no eczema: 14.7% vs. 8.0% with ≥2 conditions; P<0.0001) (Table 3). Eczema was also associated with poorer overall health (self reported excellent health: 52.2% vs. 63.4%, P<0.0001) and a higher prevalence of sleep impairment (≥ 4 nights of impaired sleep: 10.8% vs. 7.6%, P<0.0001). These associations remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P≤0.03).

Table 3. Eczema prevalence and severity are associated with poorer health outcomes and increased healthcare utilization.

| Comorbid health condition | No eczema | Eczema | P-value# | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Percent (95% CI) | Freq | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| Number of chronic conditions | |||||

| None | 54191 | 79.1 (78.4, 79.8) | 6957 | 65.5 (63.3, 67.8) | < 0.0001 |

| 1 | 9233 | 12.9 (12.3, 13.5) | 1975 | 19.7 (17.8, 21.6) | |

| 2 | 2736 | 3.8 (3.5, 4.1) | 558 | 5.3 (4.4, 6.3) | |

| 3-4 | 2156 | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) | 541 | 5.5 (4.4, 6.7) | |

| 5+ | 864 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 309 | 3.9 (2.8, 5.0) | |

| Overall health | |||||

| Excellent | 46262 | 63.4 (62.4, 64.3) | 5592 | 52.2 (49.9, 54.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Very good | 15218 | 22.1 (21.3, 22.9) | 2949 | 28.5 (26.4, 30.7) | |

| Good | 6314 | 11.5 (10.8, 12.2) | 1329 | 13.5 (12.0, 15.1) | |

| Fair | 1195 | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | 395 | 5.0 (3.8, 6.1) | |

| Poor | 197 | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | 71 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | |

| Impaired sleep (nights per week) | |||||

| 0 nights | 28199 | 64.3 (63.2, 65.3) | 3471 | 57.4 (54.4, 60.4) | < 0.0001 |

| 1-3 nights | 14628 | 27.0 (26.1, 28.0) | 2014 | 29.9 (27.2, 32.6) | |

| 4+ nights | 4179 | 7.6 (7.1, 8.1) | 651 | 10.8 (9.0, 12.7) | |

| Healthcare utilization within the past 12 months | |||||

| More services than most children same age | 7812 | 11.2 (10.6, 11.8) | 1999 | 20.7 (18.7, 22.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Seen a specialist | 16390 | 21.3 (20.6, 2.1) | 4111 | 37.4 (35.2, 29.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Number of health, mental, dental, therapy services used | |||||

| 1 of 5 | 11563 | 19.2 (18.4, 20.0) | 1556 | 16.4 (14.9, 18.0) | < 0.0001 |

| 2 of 5 | 39567 | 57.5 (56.5, 58.4) | 4698 | 44.6 (42.4, 46.9) | |

| 3 of 5 | 15897 | 20.8 (20.1, 21.6) | 3510 | 33.4 (31.2, 35.6) | |

| 4 of 5 | 2153 | 2.5 (2.3, 2.8) | 576 | 5.5 (4.4, 6.6) | |

| Comorbid health condition | Mild or moderate eczema | Severe eczema | P-value# | ||

| Freq | Percent (95% CI) | Freq | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| Number of chronic conditions | < 0.0001 | ||||

| None | 6726 | 66.9 (64.6, 69.2) | 262 | 46.1 (36.8, 55.3) | |

| 1 | 1835 | 19.6 (17.6, 21.5) | 148 | 22.1 (15.3, 28.8) | |

| 2 | 501 | 5.2 (4.2, 6.2) | 57 | 6.7 (3.7, 9.6) | |

| 3-4 | 492 | 5.2 (4.0, 6.3) | 52 | 10.9 (6.1, 15.8) | |

| 5+ | 256 | 3.2 (2.2, 4.1) | 57 | 14.2 (6.8, 21.7) | |

| Overall health | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Excellent | 5429 | 54.1 (51.7, 56.4) | 181 | 26.1 (18.6, 33.6) | |

| Very good | 2804 | 28.9 (26.7, 31.1) | 163 | 24.1 (17.4, 30.8) | |

| Good | 1197 | 12.4 (11.0, 13.9) | 141 | 28.2 (18.9, 37.5) | |

| Fair | 328 | 4.1 (3.0, 5.2) | 67 | 16.9 (9.4, 24.4) | |

| Poor | 50 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) | 22 | 4.5 (1.3, 7.8) | |

| Impaired sleep (nights per week) | 0.003 | ||||

| 0 nights | 3252 | 57.5 (54.3, 60.6) | 229 | 54.6 (43.5, 65.8) | |

| 1-3 nights | 1919 | 30.7 (27.9, 33.5) | 97 | 21.0 (13.1, 28.9) | |

| 4+ nights | 589 | 10.0 (8.2, 11.7) | 62 | 22.2 (11.1, 33.3) | |

| Healthcare utilization within the past 12 months | |||||

| More services than most children same age | 1786 | 19.3 (17.3, 21.3) | 222 | 38.5 (29.8, 47.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Seen a specialist | 3811 | 36.3 (34.1, 38.5) | 322 | 51.3 (42.1, 60.5) | 0.001 |

| Number of health, mental, dental, therapy services used | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 1 of 5 | 1519 | 16.9 (15.3, 18.5) | 47 | 11.4 (4.0, 18.9) | |

| 2 of 5 | 4526 | 45.4 (43.0, 47.7) | 188 | 34.3 (25.8, 42.7) | |

| 3 of 5 | 3267 | 32.9 (30.6, 35.2) | 257 | 38.6 (30.1, 47.1) | |

| 4 of 5 | 498 | 4.9 (3.9, 5.9) | 84 | 15.7 (8.1, 23.4) | |

Rao-Scott chi-square test

Parental refusal to answer a particular question or response of “don't know” occurred for the questions pertaining to ever eczema in 79 (0.1%), eczema severity in 22 (0.2%), number of chronic conditions in 1 (0.0002%), overall health in 18 (0.01%), impaired sleep in 493 (1.1%), more services than most children the same age in 370 (0.3%), seeing a specialist in 96 (0.1%) and number of services used in 0 (0.0%), respectively.

Note: The proportional odds assumption was not met (Score test, P<0.01). Therefore, ordinal logistic regression was not used. Rather, all analyses of severity used binary logistic regression on dichotomized severe vs. mild-moderate disease. However, similar results were obtained when severity was dichotomized moderate-severe vs. mild.

Severe eczema was associated with an even higher number of chronic health conditions (severe vs. mild–moderate: 31.8% vs. 13.6% with ≥2 conditions; P<0.0001), poorer overall health (self reported excellent health: 26.1% vs. 54.1%, P<0.0001) and a higher prevalence of sleep impairment (≥ 4 nights of impaired sleep: 22.2% vs. 10.0%, P=0.003) compared with mild–moderate eczema. These associations remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P≤0.005).

Healthcare utilization

Children with eczema reportedly used more health services than most children of the same age (20.7% vs. 11.2%, P<0.0001) (Table 3). In particular, they saw a specialist within the past 12 months more often than those without (37.4% vs. 21.3%, P<0.0001), and used a greater number of health related services, including medical, mental, dental and therapy (≥ 3 services: 38.9%% vs. 23.3%, P<0.0001). These associations remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P<0.0001).

Children with severe eczema were even more likely to report using more health services than most children of the same age (38.5% vs. 19.3%, P<0.0001), seeing a specialist within the past 12 months (51.3% vs. 36.3%, P<0.0001), and used a greater number of health related services (≥ 3 services: 54.3%% vs. 37.8%, P<0.0001) compared with mild–moderate eczema. These associations remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P≤0.003).

Recurrent ear infections

Overall, eczema was associated with higher prevalence of recurrent ear infections (eczema vs. no eczema: 10.4% vs. 6.0%, P<0.0001), but not reported severity of such infections (severe infections: 23.1% vs. 18.6%; P=0.24) (Table 4). This association remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P<0.0001).

Table 4. Eczema prevalence and/or severity are associated with recurrent ear infections, comorbid visual and dental problems.

| Comorbidity | No eczema | Eczema | P-value# | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Percent (95% CI) | Freq | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| Recurrent ear infections within the past 12 months | |||||

| Recurrent ear infections | 3849 | 6.0 (5.5, 6.5) | 1108 | 10.4 (9.3, 11.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Recurrent ear infection severity | |||||

| Mild | 1333 | 37.8 (33.8, 41.8) | 364 | 33.8 (27.8, 39.7) | 0.24 |

| Moderate | 1728 | 43.3 (39.4, 47.2) | 478 | 42.6 (37.0, 48.3) | |

| Severe | 770 | 18.6 (16.0, 21.2) | 259 | 23.1 (18.0, 28.2) | |

| Visual problems | |||||

| Ever visual problems | 1000 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 214 | 2.6 (1.5, 3.7) | 0.004 |

| Visual problems within the past 12 months | 746 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 171 | 2.2 (1.2, 3.2) | 0.002 |

| Visual problem severity | |||||

| Mild | 332 | 41.6 (34.5, 48.6) | 64 | 39.2 (13.2, 65.2) | 0.87 |

| Moderate | 258 | 36.8 (29.3, 44.3) | 65 | 41.7 (19.7, 63.5) | |

| Severe | 149 | 20.8 (15.2, 26.5) | 39 | 17.3 (6.2, 28.3) | |

| Dental problems within the past 12 months | |||||

| Toothache | 5876 | 10.3 (9.7, 10.9) | 1233 | 13.7 (12.1, 15.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Broken teeth | 1900 | 3.8 (3.3, 4.2) | 353 | 5.5 (4.0, 6.9) | 0.01 |

| Bleeding gums | 1613 | 2.9 (2.5, 3.2) | 384 | 5.0 (3.7, 6.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Tooth decay | 10303 | 21.4 (20.5, 22.4) | 1610 | 22.4 (20.0, 24.9) | 0.47 |

| Comorbidity | Mild or moderate eczema | Severe eczema | P-value# | ||

| Freq | Percent (95% CI) | Freq | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| Recurrent ear infections within the past 12 months | |||||

| Recurrent ear infections | 1029 | 10.3 (9.1, 11.5) | 89 | 13.2 (7.5, 18.8) | 0.29 |

| Recurrent ear infection severity | |||||

| Mild | 351 | 34.3 (28.4, 40.3) | 15 | 30.8 (2.8, 58.7) | 0.92 |

| Moderate | 444 | 42.5 (36.7, 48.3) | 42 | 42.3 (21.4, 63.2) | |

| Severe | 229 | 22.8 (17.5, 28.1) | 32 | 26.9 (9.9, 44.0) | |

| Visual problems | |||||

| Ever visual problems | 191 | 2.6 (1.5, 3.7) | 24 | 4.0 (0.7, 7.3) | 0.36 |

| Visual problems within the past 12 months | 149 | 2.1 (1.1, 3.2) | 22 | 4.0 (0.7, 7.2) | 0.19 |

| Visual problem severity | |||||

| Mild | 57 | 38.3 (30.4, 46.1) | 6 | 27.3 (7.1, 47.5) | 0.08 |

| Moderate | 59 | 39.6 (31.7, 47.5) | 7 | 31.8 (10.7, 53.0) | |

| Severe | 30 | 20.1 (13.6, 26.6) | 9 | 40.9 (18.6, 63.2) | |

| Dental problems within the past 12 months | |||||

| Toothache | 1138 | 13.2 (11.6, 14.9) | 104 | 20.9 (13.3, 28.6) | 0.02 |

| Broken teeth | 314 | 5.1 (3.6, 6.6) | 39 | 10.3 (4.0, 16.5) | 0.04 |

| Bleeding gums | 340 | 4.3 (3.2, 5.5) | 45 | 12.6 (5.4, 19.8) | 0.0007 |

| Tooth decay | 1490 | 21.8 (19.3, 24.3) | 127 | 32.6 (22.5, 42.7) | 0.02 |

Rao-Scott chi-square

Parental refusal to answer a particular question or response of “don't know” occurred for the questions pertaining to ever eczema in 79 (0.1%), eczema severity in 22 (0.2%), recurrent ear infections in 49 (0.1%), severity of recurrent ear infections in 25 (0.3%), ever visual problems in 100 (0.1%), current visual problems in 7 (0.005%), severity of visual problems in 10 (1.0%), toothache in 100 (0.1%), broken teeth in 33 (0.1%), bleeding gums in 89 (0.1%) and tooth decay in 213 (0.4%), respectively.

Note: The proportional odds assumption was not met (Score test, P<0.01). Therefore, ordinal logistic regression was not used. Rather, all analyses of severity used binary logistic regression on dichotomized severe vs. mild-moderate disease. However, similar results were obtained when severity was dichotomized moderate-severe vs. mild.

However, severe eczema was not associated with higher prevalence of recurrent ear infections (severe vs. mild–moderate: 13.2% vs. 10.3%, P=0.29) or severity of such infections (severe infections: 26.9% vs. 22.8%; P=0.92) in univariate or multivariate models (data not shown). However, severe eczema was associated with greater severity of recurrent ear infections in multivariate logistic regression models (P=0.003).

Visual problems

Eczema was associated with higher prevalence of ever visual problems (eczema vs. no eczema: 2.6% vs. 1.4%, P=0.004) and visual problems within the past 12 months (2.2% vs. 1.0%, P=0.002), but not severity of visual problems (severe: 17.3% vs. 20.8%; P=0.87) (Table 4). The association of eczema prevalence with ever- or current- visual problems remained significant in multivariate logistic regression models (P≤0.0016).

In contrast, severe eczema was not associated with higher prevalence of ever visual problems (severe vs. mild–moderate: 4.0% vs. 2.6%, P=0.36), visual problems in the past 12 months (4.0% vs. 2.1%, P=0.19), or severe visual problems compared with mild–moderate (40.9% vs. 20.1%; P=0.08) in univariate or multivariate models (data not shown).

Dental problems

Eczema was associated with higher prevalence of multiple dental problems within the past 6 months, including toothache (eczema vs. no eczema: 13.7% vs. 10.3%, P<0.0001), broken teeth (5.5% vs. 3.8%, P=0.01), bleeding gums (5.0% vs. 2.9%, P<0.0001), but not tooth decay (22.4% vs. 21.4%, P=0.47) (Table 4). These associations remained significant in multivariate models that included age, sex and race/ethnicity (P≤0.015).

In contrast, severe eczema was associated with higher prevalence of bleeding gums in univariate (12.6% vs. 4.3%, P=0.0007) and multivariate models (P < 0.0001). The association between severe eczema and toothache was marginally significant in univariate models (severe vs. mild–moderate: 20.9% vs. 13.2%, P=0.02) and was significant in multivariate models (P=0.0004). The association between severe eczema and broken teeth was only marginally significant in univariate models (10.3% vs. 5.1%, P=0.04) and multivariate models that included a significant interaction between severe eczema and age (P=0.04). The association between severe eczema and tooth decay was only marginally significant in univariate models (32.6% vs. 21.8%, P=0.02) but did not remain significant in multivariate models (P=0.13).

Similar results were obtained for the above mentioned health outcomes, healthcare utilization, recurrent ear infections, visual and dental problems in regression models where severity was dichotomized into moderate-severe vs. mild disease.

Discussion

Using a population-based sample, we confirmed that patients with AD carry a significant burden of comorbid disease likely contributing to the increased healthcare utilization we observed in this population. While most of the disease associations found have been previously established, the design of the current study allows for a more comprehensive and real-world assessment of the comorbid disease burden in children with AD than many previous studies. The population-based nature of the survey allows for a better estimate of the true risk of certain comorbidities compared to previous studies using hospital-based samples. In addition, our data reveal the importance of skin disease severity in not only increasing one's risk for the development of comorbid disease, but in also influencing the severity of those comorbidities.

We found that 1 in 4 children with eczema reported a history of asthma in the past 12 months and 1 in 3 reported allergic rhinitis. The association between eczema and asthma remained significant even after controlling for age, sex and race/ethnicity. These findings are in agreement with multiple previous studies demonstrating an increased asthma and/or rhinoconjunctivitis prevalence associated with AD (5-8). The prevalence of asthma in AD has ranged between 14.2-52.5% in previous studies. However, there was a broad range of asthma prevalence estimates (14.2–52.5%) (6). This variability is likely attributable to the use of smaller sample sizes, selection bias from non-population based designs and recruitment of potentially more severe eczema, and the variation in the definitions of eczema and asthma. Our estimate of 25.1% agrees with previous population-based cohort studies primarily examining European populations (6).

This is a large population-based study of the food allergy burden in children with eczema in the US population. We found that the prevalence and severity of AD are associated with both food allergy prevalence and severity. The food allergy prevalence of 15.1% in children with eczema is in agreement with the 15.7% prevalence observed in a recent study by Hanifin et al. (9). These two population-based estimates are likely more accurate estimates of the true food allergy burden in children with AD than previous hospital-based estimates (10-12). The higher prevalence of food allergies observed in those studies (37-56%) were likely a result of selecting more severe cases of AD for study.

A novel finding from our study was the direct correlation between eczema severity and the prevalence and severity of comorbidities. While several smaller studies have shown that severe AD, compared with mild AD, was associated with an increased prevalence of asthma, no study to our knowledge has examined how the severity of the skin disease may relate to the severity of the comorbidity. (7, 13-15) The causal mechanisms underlying the association between skin severity and comorbidity are not known. One explanation for this relationship is that specific genetic polymorphisms in immune regulatory elements, e.g. toll-like receptors, IL9, IL13 and its receptor, might result in immune dysregulation that simultaneously predisposes toward severe AD, asthma and food allergy (16-18). Alternatively, epidermal disruption in eczema secondary to filaggrin gene null mutations facilitates epicutaneous allergen sensitization, leading toward T helper 2 cytokine responses, and ultimately resulting in systemic inflammatory responses and atopic disease. Several clinical studies found that eczema in early childhood is a risk factor for subsequent asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis in adolescence and adulthood, even though the eczema typically remits by those ages (6, 15, 19-21). Several mouse models of AD have demonstrated evidence for this so-called “atopic march” from AD to asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis (22-24).

The poorer overall health and increased frequency of impaired sleep observed in the present study are in-line with previous studies that demonstrated impaired quality of life and sleep disturbances in AD, particularly severe AD (25-29). Similarly, the high rate of healthcare utilization observed in the present study is consistent with previous international studies that demonstrated increased referral rates to specialists and a high economic burden of AD, particularly severe AD (30-32).

The present study found a higher prevalence of recurrent ear infections in children with eczema. This is in contrast with previous studies that found an association of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis with otitis media, but not AD (33, 34). However, recurrent ear infections were not associated with eczema severity, which suggests that the relationship between AD and recurrent ear infections is complex. It is possible that the recurrent ear infections are due to the association with allergic rhinitis. Future studies are warranted to better elucidate the relationship between otitis media/ear infections and AD.

The increased prevalence of ever visual problems and visual problems in the past 12 months found in children with eczema may be a reflection of allergic conjunctivitis and/or cataracts. However, the questions in NSCH did not identify the etiology of visual problems. Although rare in children, numerous studies demonstrated increased anterior and posterior subcapsular cataracts in AD even before the advent of topical steroids (35-40). However, severe AD compared with mild-moderate was not associated with any increased visual problems, which may be merely due to the low number of children with both disorders. Previous reports argued that development of atopic cataracts is not related to eczema severity (36, 41). Future studies appear warranted to better elucidate the relationship between visual problems and AD.

Interestingly, AD, particularly severe AD, was associated with impaired dental hygiene, including: bleeding gums and toothache. Two cross-sectional studies found that periodontal disease or oral bacteria was associated with lower prevalence of dust mite allergy, asthma and/or rhinoconjunctivitis (42, 43). However, a cross-sectional study of 21,792 Japanese children found no relationship between dental caries and AD, asthma or rhinoconjunctivitis (44). Thus, while the present study is very large and population based, the data require confirmation in future clinical and translational studies. Potential mechanisms for how AD may predispose toward poorer dental hygiene include: 1) decreased attention toward brushing teeth and flossing in children who are preoccupied with the symptoms and management of their AD; 2) potentially increased oral infections secondary to impaired innate or cellular immunity 3) chronic oral, inhaled and intranasal corticosteroid usage for comorbid rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma; 4) oral antihistamine associated xerostomia; 5) mutations of fillagrin localized to the oral cavity (45-47) may predispose to impaired barrier function and integrity in the oral cavity. It is possible that atopic children with oral disease may also be predisposed to infections of other organ systems such as the sinuses or lungs. Unfortunately, the NSCH did not include any questions related to these types of infections. Future studies are warranted to elucidate these points.

The strengths of this study include being large-scale, US population-based, comprehensive survey of atopic and other comorbid disorders, and controlling for confounding demographic variables in multivariate models. However, the study also has some limitations. Eczema was defined using self-report by parental questionnaire. The NSCH question for eczema asked about “eczema or any other kind of skin allergy”. This rather broad question may result in overestimates of prevalence for AD per se by inclusion of other entities such as allergic contact dermatitis but such entities are relatively uncommon compared to AD in pediatric age groups. Moreover, previous studies similarly used single questions utilizing parental recall of physician-diagnosed eczema that have been validated (48, 49). The NSCH question asked about eczema diagnosed by a “doctor or other health care provider”, which is more specific and accurate than self-diagnosis. Parental report of severity of AD has previously been validated and was found to have moderate correlation to physician-assessed disease severity and a strong correlation with psychological comorbidity in AD (50). Thus, the results of the survey with this question are likely meaningful and accurate.

It is important to note that the impaired sleep, increased healthcare utilization and other comorbidities observed in AD are likely worsened by the presence of other comorbid asthma and hay fever. Moreover, the recurrent ear infections and dental problems observed in the study may be, in part, due to a genetic predisposition to aberrant immune responses and part of a spectrum of allergic disease.

The present study found that severity of AD was directly related to the prevalence and severity of both atopic and non-atopic comorbidities. In addition, eczema severity was associated with overall poorer health outcomes and increased healthcare utilization, as well as impaired sleep, recurrent ear infections, visual problems, and impaired dental hygiene. This study helps better understand the disease course of AD and identifies multiple important comorbidities that should be addressed by dermatologists, allergists and primary care providers alike. Moreover, it suggests that aggressive treatment to reduce the severity of eczema may reduce the risk of developing, or the severity of, the associated comorbidities. Future studies should analyze the effects of eczema prevention and treatment strategies on these comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This project was supported in part by a Mentored Patient-oriented Research Career Development Award (K23)–award number K23AR057486 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- NSCH

National Survey of Children's Health

Footnotes

Statistical analysis: JI Silverberg

Conflicts of Interest: None reported.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Previously published: No.

Bibliography

- 1.Besnier E. Premiere note et observations preliminaires pour servir d'introduction a l'etude diathesques. Annales de Dermatologie et de Syphiligraphie. 1892;4:634. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Benedetto A, Agnihothri R, McGirt LY, Bankova LG, Beck LA. Atopic dermatitis: a disease caused by innate immune defects? J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:14–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumberg SJ, Foster EB, Frasier AM, et al. Vital Health Stat 1. Vol. 55. National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Design and Operation of the National Survey of Children's Health, 2007; pp. 1–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Hulst AE, Klip H, Brand PL. Risk of developing asthma in young children with atopic eczema: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson D, Sjoberg O, Foucard T. Development of allergies and asthma in infants and young children with atopic dermatitis--a prospective follow-up to 7 years of age. Allergy. 2000;55:240–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohshima Y, Yamada A, Hiraoka M, et al. Early sensitization to house dust mite is a major risk factor for subsequent development of bronchial asthma in Japanese infants with atopic dermatitis: results of a 4-year followup study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:265–70. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanifin JM, B M, Eichenfield LF, Schneider LC, Paller AS, Preston JA, Kianifard F, Nyirady J, Zeldin RK, Figliomeni M, Spergel JM. A long-term study of safety and allergic comorbidity development in a randomized trial of pimecrolius cream in infants with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130 Abstract #328. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BA, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burks AW, James JM, Hiegel A, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity reactions. J Pediatr. 1998;132:132–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampson HA, McCaskill CC. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: evaluation of 113 patients. J Pediatr. 1985;107:669–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe AJ, Carlin JB, Bennett CM, et al. Do boys do the atopic march while girls dawdle? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121:1190–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjellman B, Hattevig G. Allergy in early and late onset of atopic dermatitis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:229–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricci G, Patrizi A, Baldi E, Menna G, Tabanelli M, Masi M. Long-term follow-up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salpietro C, Rigoli L, Miraglia Del Giudice M, et al. TLR2 and TLR4 gene polymorphisms and atopic dermatitis in Italian children: a multicenter study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:33–40. doi: 10.1177/03946320110240S408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Namkung JH, Lee JE, Kim E, et al. Association of polymorphisms in genes encoding IL-4, IL-13 and their receptors with atopic dermatitis in a Korean population. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:915–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namkung JH, Lee JE, Kim E, et al. An association between IL-9 and IL-9 receptor gene polymorphisms and atopic dermatitis in a Korean population. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;62:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess JA, Dharmage SC, Byrnes GB, et al. Childhood eczema and asthma incidence and persistence: a cohort study from childhood to middle age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:925–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin PE, Matheson MC, Gurrin L, et al. Childhood eczema and rhinitis predict atopic but not nonatopic adult asthma: a prospective cohort study over 4 decades. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1473–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spergel JM, Mizoguchi E, Brewer JP, Martin TR, Bhan AK, Geha RS. Epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen induces localized allergic dermatitis and hyperresponsiveness to methacholine after single exposure to aerosolized antigen in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1614–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrick CA, MacLeod H, Glusac E, Tigelaar RE, Bottomly K. Th2 responses induced by epicutaneous or inhalational protein exposure are differentially dependent on IL-4. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:765–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI8624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han H, Xu W, Headley MB, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)-mediated dermal inflammation aggravates experimental asthma. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:342–51. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haeck IM, ten Berge O, van Velsen SG, de Bruin-Weller MS, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, Knol MJ. Moderate correlation between quality of life and disease activity in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:236–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrelo A, Ortiz J, Alomar A, Ros S, Prieto M, Cuervo J. Atopic dermatitis: impact on quality of life and patients' attitudes toward its management. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:97–105. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monti F, Agostini F, Gobbi F, Neri E, Schianchi S, Arcangeli F. Quality of life measures in Italian children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Ital J Pediatr. 2011;37:59. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-37-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maksimovic N, Jankovic S, Marinkovic J, Sekulovic LK, Zivkovic Z, Spiric VT. Health-related quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2012;39:42–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Robaee AA, Shahzad M. Impairment quality of life in families of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt J, Schmitt NM, Kirch W, Meurer M. Outpatient care and medical treatment of children and adults with atopic eczema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:345–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stern RS, Johnson ML, DeLozier J. Utilization of physician services for dermatologic complaints. The United States, 1974. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1062–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. What is the cost of atopic dermatitis in preschool children? Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:514–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juntti H, Tikkanen S, Kokkonen J, Alho OP, Niinimaki A. Cow's milk allergy is associated with recurrent otitis media during childhood. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:867–73. doi: 10.1080/00016489950180199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentdal YE, Nafstad P, Karevold G, Kvaerner KJ. Acute otitis media in schoolchildren: allergic diseases and skin prick test positivity. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:480–5. doi: 10.1080/00016480600895128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bair B, Dodd J, Heidelberg K, Krach K. Cataracts in atopic dermatitis: a case presentation and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:585–8. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donshik PC, Hoss DM, Ehlers WH. Inflammatory and papulosquamous disorders of the skin and eye. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:533–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rich LF, Hanifin JM. Ocular complications of atopic dermatitis and other eczemas. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1985;25:61–76. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198502510-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amemiya T, Matsuda H, Uehara M. Ocular findings in atopic dermatitis with special reference to the clinical features of atopic cataract. Ophthalmologica. 1980;180:129–32. doi: 10.1159/000308965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castrow FF., 2nd Atopic cataracts versus steroid cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:64–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson RG. Cataract with atopic dermatitis; dermatologic aspects, with special reference to preoperative and postoperative care. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:433–41. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530100077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandonisio TM, Bachman JA, Sears JM. Atopic dermatitis: a case report and current clinical review of systemic and ocular manifestations. Optometry. 2001;72:94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedrich N, Volzke H, Schwahn C, et al. Inverse association between periodontitis and respiratory allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbes SJ, Jr, Sever ML, Vaughn B, Cohen EA, Zeldin DC. Oral pathogens and allergic disease: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Arakawa M, Sasaki S, Ohya Y. Dental caries and allergic disorders in Japanese children: the Ryukyus Child Health Study. J Asthma. 2008;45:795–9. doi: 10.1080/02770900802252119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Benedetto A, Qualia CM, Baroody FM, Beck LA. Filaggrin expression in oral, nasal, and esophageal mucosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1594–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SA, Dale BA. Immunologic localization of filaggrin in human oral epithelia and correlation with keratinization. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86:168–72. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12284213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reibel J, Clausen H, Dale BA, Thacher SM. Immunohistochemical analysis of stratum corneum components in oral squamous epithelia. Differentiation. 1989;41:237–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1989.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laughter D, Istvan JA, Tofte SJ, Hanifin JM. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Oregon schoolchildren. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:649–55. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kramer U, Schafer T, Behrendt H, Ring J. The influence of cultural and educational factors on the validity of symptom and diagnosis questions for atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1040–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magin PJ, Pond CD, Smith WT, Watson AB, Goode SM. Correlation and agreement of self-assessed and objective skin disease severity in a cross-sectional study of patients with acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczema. International journal of dermatology. 2011;50:1486–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.