Abstract

Significance: Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are present in both acute and chronic wounds. They play a pivotal role, with their inhibitors, in regulating extracellular matrix degradation and deposition that is essential for wound reepithelialization. The excess protease activity can lead to a chronic nonhealing wound. The timed expression and activation of MMPs in response to wounding are vital for successful wound healing. MMPs are grouped into eight families and display extensive homology within these families. This homology leads in part to the initial failure of MMP inhibitors in clinical trials and the development of alternative methods for modulating the MMP activity. MMP-knockout mouse models display altered wound healing responses, but these are often subtle phenotypic changes indicating the overlapping MMP substrate specificity and inter-MMP compensation.

Recent Advances: Recent research has identified several new MMP modulators, including photodynamic therapy, protease-absorbing dressing, microRNA regulation, signaling molecules, and peptides.

Critical Issues: Wound healing requires the controlled activity of MMPs at all stages of the wound healing process. The loss of MMP regulation is a characteristic of chronic wounds and contributes to the failure to heal.

Future Directions: Further research into how MMPs are regulated should allow the development of novel treatments for wound healing.

Matthew P. Caley, PhD

Scope and Significance

This review highlights recent advances in understanding the regulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in skin and how this knowledge might be applied in patients to improve wound healing. Selected recent advances include microRNA (MiR) regulation, novel peptides, signal transduction, experimental therapies, and novel dressings.

Translational Relevance

Wound healing is a complex multicellular process involving fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells as well as inflammatory cells. The healing process follows an orderly sequence of events incorporating four distinct, yet overlapping, phases: hemostasis, the inflammatory phase, the proliferation phase, and the remodeling phase. The phases of wound healing are regulated by cross talk between different groups of molecules, including extracellular matrix (ECM), integrins, growth factors, and MMPs. Migration of cells on ECM, and remodeling and degradation of the ECM by MMPs are key elements of wound repair.

Clinical Relevance

Chronic wounds, including pressure sores, venous ulcers, and diabetic ulcers, are a major clinical problem with considerable morbidity and associated financial costs. Excessive MMPs are a feature of chronic wounds. Regulation of MMP levels in wounds could lead to improved wound healing.

Overview

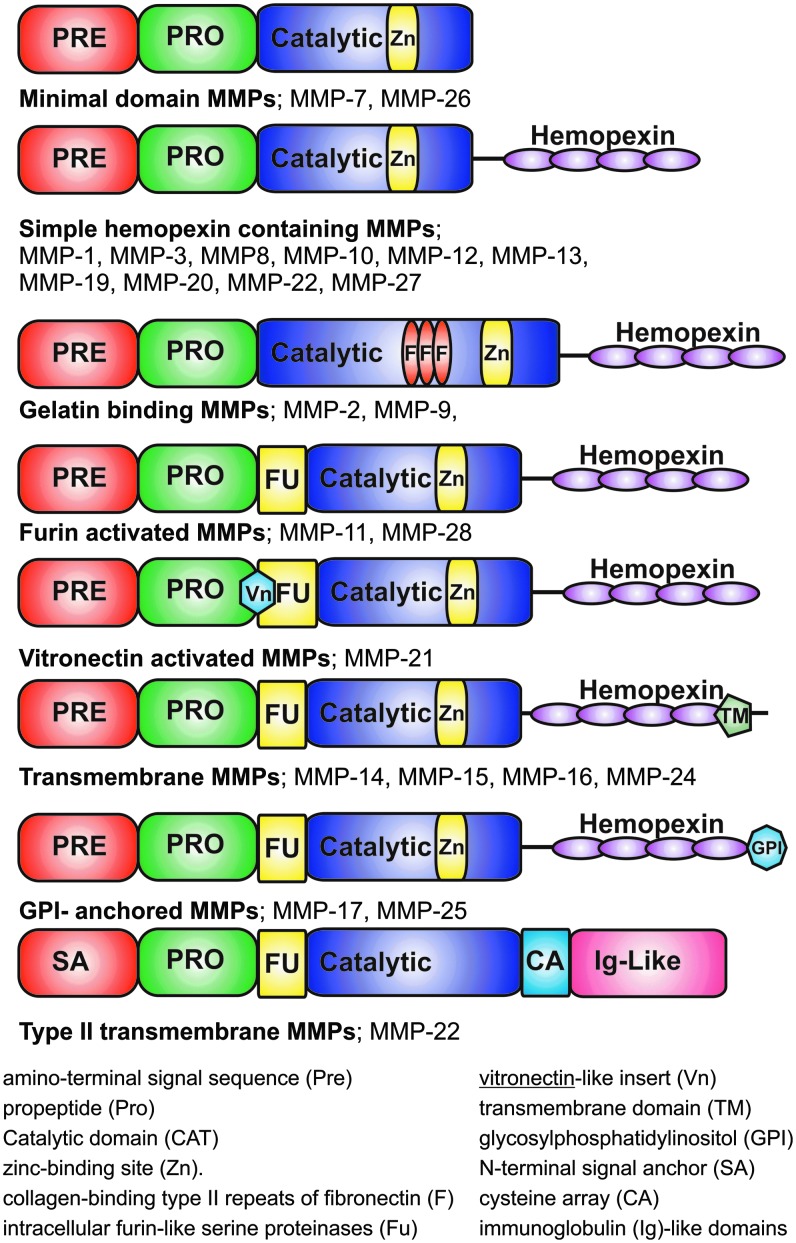

The MMP family is a group of calcium-dependent zinc-containing enzymes that are involved in the degradation of ECM. Family members share structural (Fig. 1) and sequence similarities, a flexible proline-rich hinge region, and a hemopexin-like C-terminal domain, which functions in recognition of substrates (usually ECM). Exceptions to this rule are MMP-7, MMP-23, and MMP-26, which lack the hemopexin-like domain. Some MMPs have additional insertions, which contribute to the functional differences observed between the MMP types. MMPs can be divided into seven groups based on the substrate preference and domain organization: (1) collagenases, (2) gelatinases, (3) stromelysins, (4) matrilysins, (5) metalloelastases, (6) membrane-type MMPs (MT-MMPs), and (7) other MMPs. Table 1 summarizes the different groups of human MMPs, their substrates, and role in cell migration.1–3

Figure 1.

MMP family. MMPs can be divided into eight groups based on structural similarities and shared function. Minimal domain MMPs include MMP-7 and MMP-26. Simple hemopexin containing MMPs: MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-8, MMP-10, MMP-12, MMP-13, MMP-19, MMP-20, MMP-22, and MMP-27. Gelatin binding MMPs: MMP-2 and MMP-9. Furin-activated MMPs: MMP-11 and MMP-28. Vitronectin-activated MMPs: MMP-21. Transmembrane MMPs: MMP-14, MMP-15, MMP-16, and MMP-24. GPI-anchored MMPs: MMP-17 and MMP-25. Type II transmembrane MMPs: MMP-22. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Table 1.

Mammalian matrix metalloproteinases: substrate specificities and role in wound healing

| Determined in | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member | Substrates | Role in wound healing | Cell culture | In vivo, ex vivo |

| Collagenases | ||||

| MMP-1 (collagenase-1) | Collagen I, II, III, VII, and X; aggrecan; serpins; alpha2-macroglobulin; kallikrein; chymase | Promotes human keratinocyte migration on fibrillar collagen | X | X |

| Expressed by keratinocytes at their trailing membrane edge during wound healing | ||||

| Overexpression in keratinocytes delays reepithelialization | ||||

| MMP-8 (collagenase-2) | Collagen I, II, and III; aggrecan; serpins; 2-MG | Cleaves collagens, predominant collagenase in healing wounds | X | |

| MMP-13 (collagenase-3) | Collagen I, II, III, IV, IX, X, and XIV; gelatin; fibronectin; laminin; tenascin; aggrecan; fibrillin; serpins | Promotes reepithelialization indirectly by affecting wound contraction | X | |

| Gelatinases | ||||

| MMP-2 (gelatinase A) | Gelatin; collagen I, IV, V, VII, and X; laminin; aggrecan; fibronectin; tenascin | Accelerates cell migration | X | |

| MMP-9 (gelatinase B) | Gelatin; collagen I, III, IV, V and VII; aggrecan; elastin; fibrillin | Expressed by keratinocytes at the leading edge of the wound | X | X |

| Promotes cell migration and reepithelialization except in cornea | ||||

| Stromelysins | ||||

| MMP-3 (stromelysin −1) | Collagen IV, V, IX, and X; fibronectin; elastin; gelatin; aggrecan; nidogen; fibrillin; E-cadherin | Expressed by keratinocytes at the proximal proliferating population that supplies the leading edge during wound healing | X | X |

| Affects wound contraction | ||||

| MMP-10 (stromelysin-2) | Collagen IV, V, IX, and X; fibronectin; elastin; gelatin; laminin; aggrecan, nidogen; E-cadherin | Expressed by keratinocytes at the leading edge of the wound | X | |

| MMP-11 (stromelysin-3) | Serine protease inhibitors; 1-proteinase inhibitor | Unknown | ||

| Matrilysins | ||||

| MMP-7 (matrilysin) | Elastin; fibronectin; laminin; nidogen; collagen IV; tenascin; versican; 1-proteinase inhibitor; E-cadherin; tumor necrosis factor | Required for reepithelialization of mucosal wounds | X | X |

| Metalloelastases | ||||

| MMP-12 (metalloeslastase) | Collagen IV; gelatin; fibronectin; laminin; vitronectin; elastin; fibrillin; 1-proteinase inhibitor; apolipoprotein A | Macrophage specific (not expressed by epithelial cells) | ||

| Membrane-type MMPs | ||||

| MMP-14 (MT1-MMP) | Collagen I, II, and III; gelatin; fibronectin; laminin; vitronectin; aggrecan; tenascin; nidogen; perlecan; fibrillin; 1-proteinase inhibitor; alpha2-macroglobulin; fibrin | Promotes keratinocyte outgrowth, airway reepithelialization and cell migration | X | X |

| MMP-15 (MT2-MMP) | Fibronectin; laminin; aggrecan; tenascin; nidogen; perlecan | Unknown | ||

| MMP-16 (MT3-MMP) | Collagen III; fibronectin; gelatin; casein; laminin; alpha2-macroglobulin | Unknown | ||

| MMP-17 (MT4-MMP) | Fibrin; fibrinogen; tumor necrosis factor precursor | Unknown | ||

| MMP-24 (MT5-MMP) | Progelatinase A | Unknown | ||

| MMP-25 (MT6-MMP; leukolysin) | Gelatin | Unknown | ||

| Other MMPs | ||||

| MMP-19 (RASI-1) | Gelatin; aggrecan; cartilage oligomeric matrix protein; collagen IV; laminin; nidogen; large tenascin | Unknown | ||

| MMP-20 (enamelysin) | Amelogenin; aggrecan; cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | Expressed in developing teeth | ||

| MMP-21 | Unknown | |||

| MMP-22 | Unknown | |||

| MMP-23 (CA-MMP) | Unknown | |||

| MMP-26 (endometase) | Expressed by migrating keratinocytes during cutaneous wound healing | |||

| MMP-27 | Unknown | |||

| MMP-28 (epilysin) | Casein | Expressed by a distal intact population of keratinocytes during wound healing | ||

Regulation of MMP expression and activity

Metalloproteinase secretion and activity are highly regulated. In the normal tissue, MMPs are expressed at basal levels, if at all. When tissue remodeling is required (as in wound healing), MMPs can be rapidly expressed and activated. Multiple different cell types express MMPs within the skin (keratinocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages). MMP expression can be induced in response to a range of signals, including cytokines, hormones, and contact with other cell types or the ECM.

A wide range of cytokines and growth factors transcriptionally activate MMPs; these include epidermal growth factor (EGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), as well as interleukins and interferons.4 A number of signaling pathways have been implicated in the control of MMP expression; these include activation of NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase, or Smad-dependent pathways by growth factors/cytokines; activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) by integrin activation, or activation of Wnt signaling. Further regulators of MMP expression include epigenetic modifications of chromatin and post-transcriptional regulation through mRNA stabilization/destabilization.4,5

Metalloproteinase activity is tightly regulated by gene expression as well as by controlled enzymatic activation and specific inhibition. MMPs are not initially expressed as catalytically active proteins, but in a latent form (pro-MMP). The catalytic activity of all MMPs requires a zinc ion (Zn++) in the active site. Activation involves the disruption of the bond between the prodomain PRCGVPD (this sequence is highly conserved between MMPs) and the Zn++ion in the active site.6 Pro-MMPs are activated by serine proteinases as well as by other MMPs. MMP activation can be controlled by inhibition of proteinase activity by plasma proteinase inhibitors, such as α1-proteinase and α2-macroglobulin, or by MMP binding proteins, such as thrombospondin-1 and −2.7 The major regulators of MMP are the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), which are specific inhibitors of the MMPs.8

MMPs are now known to carry out a range of diverse functions in addition to degrading or remodeling the ECM. MMPs have been shown to regulate cell–cell and cell–matrix signaling through the release of cytokines and growth factors sequestered in the ECM. MMPs modify cell surface receptors and junctional proteins, regulating processes, including cell death and inflammation. MMPs also play an important role in the release of biologically active fragments of degraded proteins, indirectly modifying cellular behavior.1,9–13 For example, within the wound environment, MT1-MMP releases a fragment from the γ-2 chain of laminin 332 (γ-2 III domain) found within the skin basement membrane; this fragment contains multiple EGF-like repeats and promotes keratinocyte migration.14,15

The role of specific MMPs in wound repair

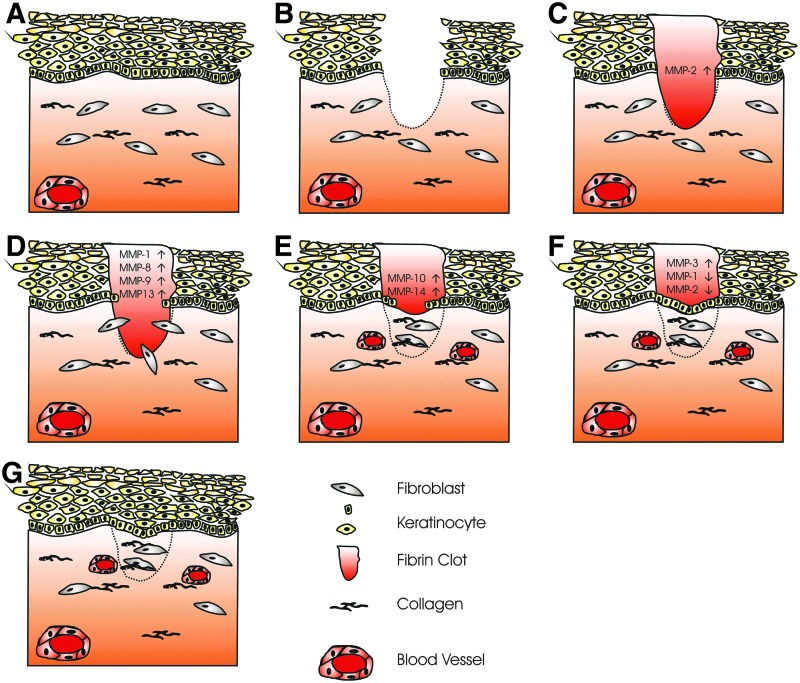

MMPs play a crucial role in all stages of wound healing by modifying the wound matrix, allowing for cell migration and tissue remodeling. Keratinocyte migration during wound healing requires the dissolution of the basal epidermal keratinocytes hemidesmosomes; this disrupts their contact with the basement membrane and allows migration through the wound matrix. Keratinocytes either migrate through the provisional wound matrix (consisting of fibronectin and fibrin) or migrate in contact with the dermis underlying this matrix. The ECM that the keratinocyte interacts with determines the integrins that are activated; α5β1 and αvβ6 integrins are activated on contact with fibronectin, α3β1 and α6β4 integrins bind to laminin-332, and α2β1 integrin is a collagen receptor.16,17 MMP expression and activity are tightly controlled during wound healing; specific MMPs are confined to particular locations in the wound and to specific stages of wound repair (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Wound healing. Healthy skin consists of a stratified squamous epithelium, basement membrane, and dermis (A). The epithelium is made up of basal keratinocytes (proliferative) and stratified suprabasal keratinocytes (differentiating), which eventually lose their nuclear material. The dermis is made up of extracellular matrix, predominantly collagen, is populated by fibroblasts, and contains the blood vessels that supply the skin. (B) A full-thickness wound of the skin damaging both epidermis and dermis. (C) Inflammatory phase, the wound is filled with a fibrin clot sealing the wound, MMP-2 expression is increased. (D) Fibroblasts migrate into the wound area; using MMPs, they remodel the fibrin clot replacing it with new extracellular matrix. Epithelial cells upregulate MMP expression and migrate into the wound area (E). Failure to remodel the extracellular matrix due to increased MMP expression or inflammation is seen in chronic wounds and plays a part in their failure to heal. (F) Reepithelialization: epithelial cells migrate from the surrounding epithelium, proliferating and closing the wound. Expression of promigratory MMPs is decreased and tissue remodeling MMP expression is increased. (G) Wound maturation: epithelial cells proliferate and differentiate reforming the stratified squamous epithelium. Fibroblasts continue to remodel the underlying dermis over a period of several months.

Epithelial, stromal, or inflammatory cell expression of MMPs can control inflammation in the wound area through the regulation of chemokine activity.18 MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 are the major chemokine regulators during wound healing, degrading chemokines by proteolysis to remove them entirely or to generate receptor antagonists (reviewed by Gill and Parks19).

MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13 (interstitial collagenases)

The loss of ECM during wound healing triggers the rapid expression of MMP-1 in basal keratinocytes at the migrating epithelial front in wounds.20 MMP-1 expression is controlled by the binding of type I collagen to α2β1 integrin. The MMP-1 expression is induced when cells are in contact with type I collagen promoting migration.21 For sustained MMP-1 expression, cross talk between α2β1 integrin and the EGF receptor is required.22 The MMP-1 expression peaks at day 1 after wounding in migrating basal keratinocytes at the wound edge followed by a gradual decrease until re-epithelialization is complete. Laminin isoforms expressed during the final stage of tissue remodeling in keratinocytes act as a signal for the downregulation of MMP-1.23 Downregulation of MMP-1 seems to be important for normal tissue remodeling as there are high levels of MMP-1 in chronic nonhealing wounds. MMP-8 is another interstitial collagenase that is secreted by wound fibroblasts, neutrophils, and macrophages. An increased expression of MMP-8 in chronic wounds is detrimental to wound repair causing breakdown of type I collagen.24 Another collagenase, MMP-13, which is expressed by fibroblasts deep in the chronic wound bed, plays an important role in the maturation of granulation tissue, including modulating myofibroblast function, inflammation, angiogenesis, and degradation of matrix.25

MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B)

The presence of active MMP-2 and MMP-9 in wound fluids initially identified a role for these MMPs in wound healing.26 The MMP-2 expression at the edge of acute wounds is linked with the expression of laminin-332 and increased keratinocyte migration.27 Laminin-332 has been shown to have dual functions in migration, dependent on the processing of the protein. MMP-2 and MT1-MMP cleave the γ-2 chain of laminin-332 creating a promigratory fragment that triggers cell migration. The cleaved fragment contains multiple EGF-like repeats and acts as a cryptic ligand. The fragment is only found in tissues undergoing remodeling and tumors.14,15,28

Metalloproteinase-9 is expressed in several injured epithelia, including the eye, skin, gut, and lung, playing a role in wound healing and cell signaling.29–32 MMP-9 plays an important role in keratinocyte migration; it is expressed at the leading edges of migrating keratinocytes during wound closure. MMP-9 knockout (KO) mice display delayed wound closure highlighting the importance of MMP-9 in wound healing.33 Hypoxia, a feature of chronic wounds, increases keratinocyte migration and MMP-9 activity.34,35 In MMP-9-deficient mice, MMP-9 has also been shown to inhibit cell proliferation through Smad2 signaling delaying corneal wound healing.31

Angiogenesis is an important process during wound healing, with the generation of blood vessel-rich granulation tissue, a critical step in tissue regeneration. Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 play a role in regulating angiogenesis during wound healing through the activation of proangiogenic cytokines, including TNF-α and VEGF, and by generating antiangiogenic peptides (e.g., endostatin from type XVII collagen, expressed in the basement membrane).36,37 Other members of the MMP family of proteins have also been shown to produce the antiangiogenic fragments, endostatin from type XVII collagen (MMP-3, −7, −9, −13, and −20) and angiostatin from plasminogen (MMP-2, −3, −7, −9, and −12) in vitro.36,38,39

MMP-3 and MMP-10 (stromelysin-1 and −2)

MMP-3 and MMP-10 degrade several collagens (MMP-3 collagen II, III, IV, IX, and X; MMP-10 collagen III, IV, and V) as well as noncollagenous connective tissue macromolecules, including proteoglycans, laminin, and fibronectin.40 MMP-3 and MMP-10 have distinct expression patterns during wound healing; MMP-3 is expressed adjacent to the wound edge by proliferating cells, whereas MMP-10 colocalizes with MMP-1 at the leading edge of the wound. The distinct patterns of MMP-3 and MMP-10 expression in keratinocytes are thought to be controlled by ECM contact. MMP-3-expressing cells are in contact with an intact basement membrane, whereas MMP-10 expression is seen in cells migrating on type I collagen.41 Another factor controlling expression are the cytokines EGF, TGF-β1, and TNF-α, which have been shown to regulate the expression of MMP-10 expression.42 The regulation of MMP-10 expression and activation during wound healing is tightly controlled; uncontrolled MMP-10 expression results in a disorganized migrating epithelium, degradation of newly formed matrix, aberrant cell–cell contacts of the migrating keratinocytes, and an increased rate of cell death of wound edge keratinocytes.43 MMP-3 regulates the rate of wound healing through its role in wound contraction.44 It can also activate several pro-MMPs as well as increase bioavailability of many cytokines, such as HB-EGF and basic FGF.45,46

MT1-MMP (MMP-14)

MT1-MMP plays a pivotal role in cell migration during wound healing.47 The MT1-MMP expression is localized to keratinocytes in the migrating front of the wound. MT1-MMP activates MMP-2 through degradation of pro-MMP-2, a coordinated process involving two molecules of MT1-MMP and also TIMP-2.48 The loss of MT1-MMP leads to defective type I collagen turnover and loss of MMP-2 activation.49,50 MT1-MMP acts to regulate epithelial cell proliferation during wound healing by altering the expression of the KGF receptor.51 In addition to controlling proliferation, MT1-MMP also accelerates epithelial cell migration in vitro through the cleavage of syndecan-1, CD44, and laminin-332.14,52,53

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

The endogenous regulators of the MMP activity are the TIMPs; they are 20–39 kDa secreted proteins and are able to inhibit a range of MMPs. Through the modulation of the MMP activity, TIMPs play an important role in regulating cell migration in wound healing. TIMP-1 (inhibits MMP-1, −2, −3, −7, −8, −9, −10, −11, −12, −13, and −16) is present in epithelial cells of healing excisional and burn wounds, and it is also expressed in wound fibroblasts, especially in fibroblasts adjacent to blood vessels in humans.54,55 TIMP-2 (inhibits MMP-1, −2, −3, −7, −8, −9, −10, −13, −14, −15, −16, and −19) has been shown to both impair53 and accelerate56 cell migration in vitro. TIMP-3 (inhibits MMP-1, −2, −3, −7, −9, −13, −14, and −15) plays a role in controlling ECM remodeling during wound healing. This was clearly demonstrated using Timp3 knockout mice, which displayed abnormal collagen and fibronectin remodeling.57

Advances in Regulation of MMPs

Signal transduction mechanisms regulating MMP expression

There is some evidence to suggest that chronic complications of diabetes mellitus, such as nephropathy and skin lesions, are related to the local expression of components of the renin–angiotensin system. Angiotensin II and its receptors are overexpressed in diabetic skin fibroblasts. Angiotensin II has been shown to stimulate TGF-β secretion through AT1 receptors leading to increased TIMP-1 and type I and III procollagen production in diabetic skin animal models.58 Losartan, an AT1 receptor inhibitor, can reverse this effect in fibroblasts.

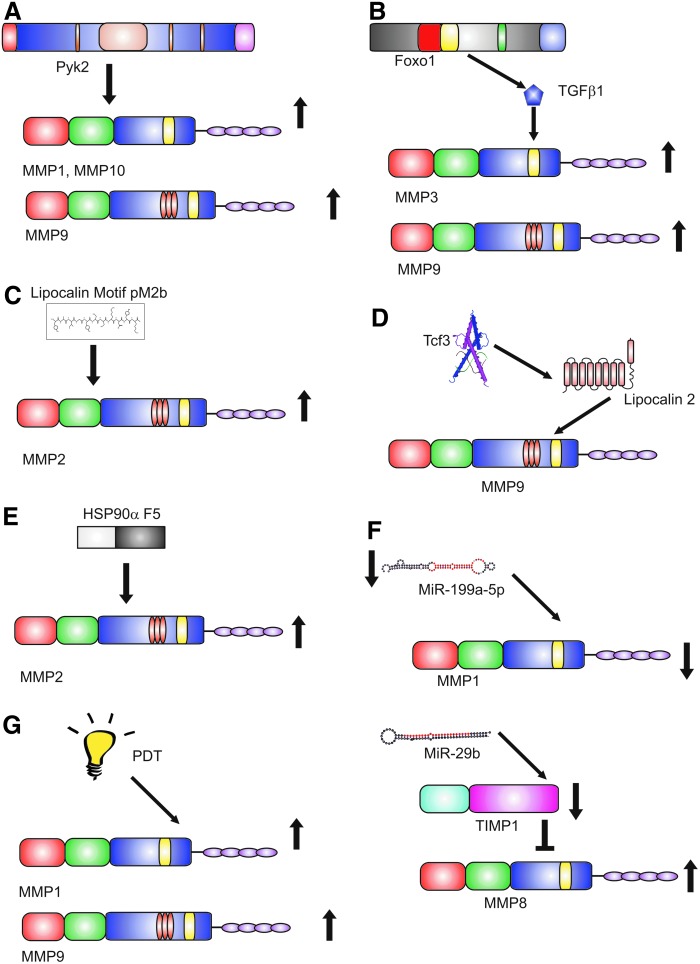

Proline-rich protein tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2), an important member of the FAK family, has recently been shown to play an important role in wound healing.59 Wound closure is delayed in Pyk2-KO mice. Epidermal keratinocytes derived from the KO mouse displayed decreased migration. The overexpression of Pyk2 in human epidermal keratinocytes increased migration and was associated with the increased expression of MMP-1, −9, and −10. These data suggest that Pyk2 is an important regulator of both keratinocyte migration and MMP expression and is worthy of further study in human wounds (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Novel regulation of MMPs. Recent advances in the regulation of MMP expression and activity have used a variety of mechanisms. (A) Pyk2 has been shown to increase the expression of MMP-1, −9, and −10 in mouse models. (B) FOXO1, a member of the forkhead family of transcription factors, upregulates TGFβ1 leading to an increase in MMP-3 and MMP-9. (C) The 12 peptide fragment comprising the lipocalin conserved motif pM2b have been shown to increase MMP-2 in rat models of wounding. (D) Tcf3 increases secretion of lipocalin 2, which stabilizes MMP-9 increasing activity. (E) A 115 amino acid fragment (F5) of Hsp90α increases the secretion of MMP-2. (F) MiR, small hairpin loops of noncoding RNA, have been shown to regulate the MMP activity in wound models. (G) PDT has been shown to increase the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-9. MiR, microRNA; PDT, photodynamic therapy; Pyk2, proline-rich protein tyrosine kinase 2; Tcf3, transcription factor 3; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

The forkhead family member, FOXO1, coordinates the response of keratinocytes to wounding by upregulating TGF-β1 leading to increased MMP-3 and MMP-9 secretion.60 Moreover, FOXO1 reduces oxidative stress in keratinocytes preventing apoptosis and facilitating wound healing (Fig. 3B).

Peptide modulation of MMP expression

Lipocalins are multifunctional proteins that have been shown to play a role in response to injury. Lipocalins are abundant in the venom of the Lonomia obliqua caterpillar. A peptide comprising the sequence of a lipocalin conserved motif (pM2b) promoted wound healing in a full-thickness rat skin wound model with an increase in collagen and MMP-2 activity. Reduced scarring was also observed (Fig. 3C).61

Lipocalin-2 is known to bind to and stabilize MMP-962 and was identified as a key secreted factor promoting cell migration in vitro and wound healing in vivo.63 Lipocalin-2 secretion is regulated by the transcription factor, Tcf3, which also regulates embryonic and adult skin stem cell functions. Tcf3 is upregulated in skin wounds, and Tcf3 overexpression increases keratinocyte migration and skin wound healing. The transcription factor, Stat3, is an upstream regulator of Tcf3.63 Lipocalin-derived peptides may be promising tools to develop new formulations to aid wound healing (Fig. 3D).

Normal keratinocytes secrete heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) in response to tissue injury; Hsp90α in cancer increases MMP-2 secretion. Extracellular Hsp90 is able to promote cell migration in the presence of the inhibitory effect of TGF-β. It is a common promigratory factor for keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, and dermal endothelial cells. A 115 amino acid fragment of Hsp90α, F5, promoted healing of murine diabetic wounds far more effectively than conventional growth factors, suggesting promise in human wound healing (Fig. 3E).64

MiR regulation of MMPs

MiR are a recently discovered class of noncoding RNAs that play a key role in regulation of gene expression. At the post-transcriptional level, they are thought to regulate the expression of 30% of all human protein-coding genes. They are short single molecules about 22 nucleotides in length. Downregulation of MiR-199a-5p induces wound angiogenesis by derepressing the MMP-1 expression through the transcription factor V-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1 (Ets-1).65 MiR 29b is a known regulator of TGF-β-mediated fibrosis. Delivery of MiR-29b through a collagen scaffold to full-thickness wounds in vivo reduced wound contraction, improved the ratio of collagen type III/I, and increased the ratio of MMP-8:TIMP-1 resulting in improved ECM remodeling66 showing the potential of MiR therapy in wound healing (Fig. 3F).

Regulation of MMPs using photodynamic therapy

Topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) is widely used for nonmelanoma skin cancer. It uses a photosensitizing agent and light source to cause altered cell signaling, cell damage, and death. A controlled study of methyl aminolevulinate-PDT in excisional wounds showed that PDT-treated wounds had increased MMP-1, MMP-9, and TGF-β3 production during matrix remodeling with better organization of collagen and smaller scars compared to control wounds from the same patient (Fig. 3G).67

Regulation of MMPs using dressings

Wound dressings containing superabsorbent polymers have been devised. They are generated from acrylic acid and a cross-linker by polymerization. Dressings incorporating polyacrylate have a high density of ionic charges and absorb wound exudate. These dressings can bind MMPs and reduce their activity in vitro.68 These dressings also have the potential to inhibit the activity of bacterial proteases, such as those secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.69

Take-Home Messages.

• MMPs play a vital role in wound healing; however, excessive expression of MMPs seen in chronic wounds may inhibit wound closure.

• MMPs are substrate specific; however, one growth factor may regulate multiple different MMPs making them hard to target.

• Novel mechanisms for regulating MMPs are being investigated using signal transduction, peptides, and MiRs to modulate MMP expression and activity.

• Existing treatments like PDT may have a role in controlling the MMP activity.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- Hsp90

heat shock protein 90

- KGF

keratinocyte growth factor

- KO

knockout

- MiR

microRNAs

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MT

membrane-type

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- Pyk2

proline-rich protein tyrosine kinase 2

- Tcf3

transcription factor 3

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TIMP

tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

No funding sources were obtained for this review article.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

The authors have no conflicts of interest, the content of this article was expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Dr. Matthew P. Caley, PhD, gained his BSc with honors in Molecular Biology from the University of Edinburgh in 2003, his MRes in Biomolecular Science from the University of York in 2004, and his PhD from the Cardiff University in 2008 studying chronic wounds and wound healing. He is currently working in the Centre for Cutaneous Research at the Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry investigating the role of extracellular matrix in cancer progression. Dr. Vera L.C. Martins gained her MSc in Plant Biology from the Lisbon University in 2003 and her PhD from the Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University London in 2008 studying the role of collagen VII in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dr. Vera has continued her research into collagen VII in the Centre for Cutaneous Research at the Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry. Prof. Edel A. O'Toole received her medical degree from the University College, Galway, and completed her training in Medicine and Dermatology in Galway and Dublin. She was awarded a Dermatology Foundation and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Physician–Scientist Fellowship to study keratinocyte migration at the Northwestern University in Chicago. In 1998, she completed her clinical training in Dermatology at the Royal Free and Barts and the London NHS Trusts, and in 2001, she became a Clinical Senior Lecturer/Honorary Consultant Dermatologist at QMUL/Barts and the London NHS Trust. In 2009, she became the Professor of Molecular Dermatology at the Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University London.

References

- 1.Chen P, Parks WC. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in epithelial migration. J Cell Biochem 2009;108:1233–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Nothnick WB. The role and regulation of the uterine matrix metalloproteinase system in menstruating and non-menstruating species. Front Biosci 2005;10:353–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffensen B, Hakkinen L, Larjava H. Proteolytic events of wound-healing—coordinated interactions among matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), integrins, and extracellular matrix molecules. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2001;12:373–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J Cell Physiol 2007;211:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toriseva M, Kahari VM. Proteinases in cutaneous wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009;66:203–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Wart HE, Birkedal-Hansen H. The cysteine switch: a principle of regulation of metalloproteinase activity with potential applicability to the entire matrix metalloproteinase gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990;87:5578–5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sottrup-Jensen L, Birkedal-Hansen H. Human fibroblast collagenase-alpha-macroglobulin interactions. Localization of cleavage sites in the bait regions of five mammalian alpha-macroglobulins. J Biol Chem 1989;264:393–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Sci 2002;115:3719–3727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi E, Fridman R, Miao HQ, Ma YS, Yayon A, Vlodavsky I. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 releases active soluble ectodomain of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:7069–7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson CL, Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, et al. Regulation of intestinal alpha-defensin activation by the metalloproteinase matrilysin in innate host defense. Science 1999;286:113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell 2002;111:635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuire JK, Li Q, Parks WC. Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) mediates E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in injured lung epithelium. Am J Pathol 2003;162:1831–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Lint P, Libert C. Chemokine and cytokine processing by matrix metalloproteinases and its effect on leukocyte migration and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 2007;82:1375–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koshikawa N, Giannelli G, Cirulli V, Miyazaki K, Quaranta V. Role of cell surface metalloprotease MT1-MMP in epithelial cell migration over laminin-5. J Cell Biol 2000;148:615–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilles C, Polette M, Coraux C, et al. Contribution of MT1-MMP and of human laminin-5 gamma2 chain degradation to mammary epithelial cell migration. J Cell Sci 2001;114:2967–2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larjava H, Haapasalmi K, Salo T, Wiebe C, Uitto VJ. Keratinocyte integrins in wound healing and chronic inflammation of the human periodontium. Oral Dis 1996;2:77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakkinen L, Uitto VJ, Larjava H. Cell biology of gingival wound healing. Periodontol 2000 2000;24:127–152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill SE, Parks WC. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: regulators of wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008;40:1334–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saarialho-Kere UK, Kovacs SO, Pentland AP, Olerud JE, Welgus HG, Parks WC. Cell-matrix interactions modulate interstitial collagenase expression by human keratinocytes actively involved in wound healing. J Clin Invest 1993;92:2858–2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilcher BK, Dumin JA, Sudbeck BD, Krane SM, Welgus HG, Parks WC. The activity of collagenase-1 is required for keratinocyte migration on a type I collagen matrix. J Cell Biol 1997;137:1445–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilcher BK, Dumin J, Schwartz MJ, et al. Keratinocyte collagenase-1 expression requires an epidermal growth factor receptor autocrine mechanism. J Biol Chem 1999;274:10372–10381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudbeck BD, Pilcher BK, Welgus HG, Parks WC. Induction and repression of collagenase-1 by keratinocytes is controlled by distinct components of different extracellular matrix compartments. J Biol Chem 1997;272:22103–22110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danielsen PL, Holst AV, Maltesen HR, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 overexpression prevents proper tissue repair. Surgery 2011;150:897–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toriseva M, Laato M, Carpen O, et al. MMP-13 regulates growth of wound granulation tissue and modulates gene expression signatures involved in inflammation, proteolysis, and cell viability. PloS One 2012;7:e42596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salo T, Makela M, Kylmaniemi M, Autio-Harmainen H, Larjava H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and −9 during early human wound healing. Lab Invest 1994;70:176–182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moses MA, Marikovsky M, Harper JW, et al. Temporal study of the activity of matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors during wound healing. J Cell Biochem 1996;60:379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quaranta V. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloprotease-2 cleavage of laminin-5. Science 1997;277:225–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fini ME, Parks WC, Rinehart WB, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in failure to re-epithelialize after corneal injury. Am J Pathol 1996;149:1287–1302 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betsuyaku T, Fukuda Y, Parks WC, Shipley JM, Senior RM. Gelatinase B is required for alveolar bronchiolization after intratracheal bleomycin. Am J Pathol 2000;157:525–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohan R, Chintala SK, Jung JC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) coordinates and effects epithelial regeneration. J Biol Chem 2002;277:2065–2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castaneda FE, Walia B, Vijay-Kumar M, et al. Targeted deletion of metalloproteinase 9 attenuates experimental colitis in mice: central role of epithelial-derived MMP. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1991–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hattori N, Mochizuki S, Kishi K, et al. MMP-13 plays a role in keratinocyte migration, angiogenesis, and contraction in mouse skin wound healing. Am J Pathol 2009;175:533–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Toole EA, Marinkovich MP, Peavey CL, et al. Hypoxia increases human keratinocyte motility on connective tissue. J Clin Invest 1997;100:2881–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulholland B, Tuft SJ, Khaw PT. Matrix metalloproteinase distribution during early corneal wound healing. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:584–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heljasvaara R, Nyberg P, Luostarinen J, et al. Generation of biologically active endostatin fragments from human collagen XVIII by distinct matrix metalloproteases. Exp Cell Res 2005;307:292–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato T, Kure T, Chang JH, et al. Diminished corneal angiogenesis in gelatinase A-deficient mice. FEBS Lett 2001;508:187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Reilly MS, Wiederschain D, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Folkman J, Moses MA. Regulation of angiostatin production by matrix metalloproteinase-2 in a model of concomitant resistance. J Biol Chem 1999;274:29568–29571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornelius LA, Nehring LC, Harding E, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases generate angiostatin: effects on neovascularization. J Immunol 1998;161:6845–6852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy G, Cockett MI, Ward RV, Docherty AJ. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of elastin, type IV collagen and proteoglycan. A quantitative comparison of the activities of 95 kDa and 72 kDa gelatinases, stromelysins-1 and −2 and punctuated metalloproteinase (PUMP). Biochem J 1991;277(Pt 1):277–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saarialho-Kere UK, Pentland AP, Birkedal-Hansen H, Parks WC, Welgus HG. Distinct populations of basal keratinocytes express stromelysin-1 and stromelysin-2 in chronic wounds. J Clin Invest 1994;94:79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rechardt O, Elomaa O, Vaalamo M, et al. Stromelysin-2 is upregulated during normal wound repair and is induced by cytokines. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:778–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krampert M, Bloch W, Sasaki T, et al. Activities of the matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-2 (MMP-10) in matrix degradation and keratinocyte organization in wounded skin. Mol Biol Cell 2004;15:5242–5254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bullard KM, Lund L, Mudgett JS, et al. Impaired wound contraction in stromelysin-1-deficient mice. Ann Surg 1999;230:260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res 2003;92:827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitelock JM, Murdoch AD, Iozzo RV, Underwood PA. The degradation of human endothelial cell-derived perlecan and release of bound basic fibroblast growth factor by stromelysin, collagenase, plasmin, and heparanases. J Biol Chem 1996;271:10079–10086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seiki M. The cell surface: the stage for matrix metalloproteinase regulation of migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002;14:624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strongin AY, Collier I, Bannikov G, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Goldberg GI. Mechanism of cell surface activation of 72-kDa type IV collagenase. Isolation of the activated form of the membrane metalloprotease. J Biol Chem 1995;270:5331–5338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmbeck K, Bianco P, Caterina J, et al. MT1-MMP-deficient mice develop dwarfism, osteopenia, arthritis, and connective tissue disease due to inadequate collagen turnover. Cell 1999;99:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Z, Apte SS, Soininen R, et al. Impaired endochondral ossification and angiogenesis in mice deficient in membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:4052–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atkinson JJ, Toennies HM, Holmbeck K, Senior RM. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase is necessary for distal airway epithelial repair and keratinocyte growth factor receptor expression after acute injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L600–L610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kajita M, Itoh Y, Chiba T, et al. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase cleaves CD44 and promotes cell migration. J Cell Biol 2001;153:893–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Endo K, Takino T, Miyamori H, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 stimulates cell migration. J Biol Chem 2003;278:40764–40770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaalamo M, Leivo T, Saarialho-Kere U. Differential expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, −2, −3, and −4) in normal and aberrant wound healing. Human Pathol 1999;30:795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaalamo M, Weckroth M, Puolakkainen P, et al. Patterns of matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP-1 expression in chronic and normally healing human cutaneous wounds. Br J Dermatol 1996;135:52–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terasaki K, Kanzaki T, Aoki T, Iwata K, Saiki I. Effects of recombinant human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (rh-TIMP-2) on migration of epidermal keratinocytes in vitro and wound healing in vivo. J Dermatol 2003;30:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gill SE, Pape MC, Khokha R, Watson AJ, Leco KJ. A null mutation for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (Timp-3) impairs murine bronchiole branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2003;261:313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ren M, Hao S, Yang C, et al. Angiotensin II regulates collagen metabolism through modulating tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in diabetic skin tissues. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2013;10:426–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koppel AC, Kiss A, Hindes A, et al. Delayed skin wound repair in proline-rich protein tyrosine kinase 2 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014;306:C899–C909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ponugoti B, Xu F, Zhang C, Tian C, Pacios S, Graves DT. FOXO1 promotes wound healing through the up-regulation of TGF-beta1 and prevention of oxidative stress. J Cell Biol 2013;203:327–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilian L, Christian L, Andrade SA, et al. Wound healing effects of a lipocalin-derived peptide. J Clin Toxicol 2014;4:6 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan L, Borregaard N, Kjeldsen L, Moses MA. The high molecular weight urinary matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity is a complex of gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Modulation of MMP-9 activity by NGAL. J Biol Chem 2001;276:37258–37265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miao Q, Ku AT, Nishino Y, et al. Tcf3 promotes cell migration and wound repair through regulation of lipocalin 2. Nat Commun 2014;5:4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng C-F, Sahu D, Tsen F, et al. A fragment of secreted Hsp90α carries properties that enable it to accelerate effectively both acute and diabetic wound healing in mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:4348–4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chan YC, Roy S, Huang Y, Khanna S, Sen CK. The microRNA miR-199a-5p down-regulation switches on wound angiogenesis by derepressing the v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1-matrix metalloproteinase-1 pathway. J Biol Chem 2012;287:41032–41043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monaghan M, Browne S, Schenke-Layland K, Pandit A. A collagen-based scaffold delivering exogenous microrna-29B to modulate extracellular matrix remodeling. Mol Ther 2014;22:786–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mills SJ, Farrar MD, Ashcroft GS, Griffiths CE, Hardman MJ, Rhodes LE. Topical photodynamic therapy following excisional wounding of human skin increases production of transforming growth factor-beta3 and matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 9, with associated improvement in dermal matrix organization. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiegand C, Hipler UC. A superabsorbent polymer-containing wound dressing efficiently sequesters MMPs and inhibits collagenase activity in vitro. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2013;24:2473–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCarty SM, Percival SL, Clegg PD, Cochrane CA. The role of polyphosphates in the sequestration of matrix metalloproteinases. Int Wound J 2015;12:89–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]