Abstract

Although Latino and other immigrant populations are the driving force behind population increases in the U.S., there are significant gaps in knowledge and practice on addressing health disparities in these populations. The Avance Center for the Advancement of Immigrant/Refugee Health, a health disparities research center in the Washington, DC area, includes as part of its mission a multi-level, participatory community intervention (called Adelante) to address the co-occurrence of substance abuse, violence and sex risk among Latino immigrant youth and young adults. Research staff and community partners knew that the intervention community had grown beyond its Census-designated place (CDP) boundaries, and that connection and attachment to community were relevant to an intervention. Thus, in order to understand current geographic and social boundaries of the community for sampling, data collection, intervention design and implementation, the research team conducted an ethnographic study to identify self-defined community boundaries, both geographic and social. Beginning with preliminary data from a pilot intervention and the original CDP map, the research included: geo-mapping de-identified addresses of service clients from a major community organization; key informant interviews; and observation and intercept interviews in the community. The results provided an expanded community boundary profile and important information about community identity.

Keywords: Ethnographic community mapping, Latino health disparities, Latino youth, community intervention

BACKGROUND

The Washington, DC metropolitan area has been a destination for an increasing number of immigrants and refugees from multiple countries of origin. Mirroring national trends, and particularly the most recent Census data (http://www.census.gov), Latino immigrants and refugees are the largest of these populations. Newcomers from Central America began to arrive in the DC metro area in significant numbers during the late 1970s and 1980s, fleeing from civil strife in El Salvador, Guatemala, and other Central American countries, and their numbers have since grown substantially in all parts of the region.

Though Latino immigrants face significant health disparities, research and knowledge about effective program approaches have not kept up with population needs. In this paper we briefly describe the background for a community-level health disparities intervention that aims to help close this gap, and the ethnographic methods used to define the community for purposes of sampling, to determine the location and focus of intervention activities, and to gain preliminary insight with respect to community identity and social boundaries. As an additional key theme, we also describe the role of ethnographic and qualitative methods in helping to shape an intervention that treats the community as a whole phenomenon, juxtaposed against the more prevalent tendency within public health to decontextualize specific causal factors for purposes of intervention.

Addressing a health disparities cluster

To better understand the need for the ethnographic community definition effort, it is useful to begin with a description of the intervention and its rationale. The Avance Center for the Advancement of Immigrant/Refugee Health, an exploratory health disparities research center in the Washington, DC metropolitan area, is funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) as a university-community collaboration. The Avance Center’s work is based on a context-driven conceptualization of health disparities as the outcome of multiple contributing factors, interacting within what could be called a social ecology of disparities. The term “ecology” is intentionally employed here to frame the contributing factors as interconnected in a holistic sense, and to do so using a term that has increasingly been adopted in public health planning models (Green & Kreuter 1999; WHO 2014), though, we would argue, primarily in the acknowledgment that there are multiple levels of causation, e.g., individual level, family level, community level, and so on, rather than in the connectedness between levels or as an integrated phenomenon situated within a broader structural context.

From our perspective, health disparities and their contributing factors typically occur in related clusters, as a syndemic (see Singer & Clair 2003; Singer 1994), arguing for intervention approaches that target shared contributing factors as a whole complex. Recent commentaries and reviews of efforts to redress health disparities (Edberg et al. 2010; Starfield 2007) support the identification of shared contributing factors that, over time, create “pathways” or trajectories of health and vulnerability that may be unique to specific population groups.

Among Latino immigrant populations, one such health disparities cluster affecting youth is associated with substance abuse, and includes family/partner violence, other interpersonal violence, and sexual risk. For purposes of the intervention discussed here, substance abuse is therefore viewed as a key element within a vulnerability cluster that, as a co-occurring syndrome, is disproportionately high among Latino youth (Martinez Jr. 2006; Martinez, Eddy & DeGarmo, 2003; Vega & Gil, 1999). There is evidence that substance abuse and related health problems among Latino youth have increased, particularly for youth who are more acculturated or born in the U.S. (Martinez Jr. 2006; Martinez, Eddy & DeGarmo, 2003; Vega & Gil, 1999; Edberg et al. 2009).

It is important to note that these data on health disparities among Latino youth include both historic and more recent immigrant Latino population subgroups. However, in order to understand the problem in context, we make a distinction between the terms “Latino” and “Latino immigrant” in order to account for conditions and circumstances that are germane for the latter, but not necessarily the former group. Latino populations have lived in North America since the 16th century, and there are many areas of the country where such longstanding – or “historic” -- Latino populations are common. By contrast, our reference to Latino immigrants largely includes Central and South Americans, as well as Mexicans, who emigrated to the U.S. due to specific civil conflicts and economic need since approximately the 1980s, along with their children. This definition reflects a significant proportion of the recent Latino population increase – a 137% increase for Central Americans between 2000 and 2010; 104% for South Americans, compared to a 54% increase in immigrants from Mexico over the same period (U.S. Census, The Hispanic Population 2010. Table 1, Hispanic or Latino Origin by Type, 2000-2010). These are new or recent immigrants, compared to longstanding Mexican-American residents in the Southwest, Puerto Ricans in New York and New Jersey, or Cuban-Americans in Florida.

The Adelante Intervention – Incorporating a Holistic Frame of Reference

The Avance Center encompasses several areas of activity in collaboration with the Latino immigrant community of Langley Park, MD, in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. As a central part of its mission, the Center is tasked with developing, implementing and testing an intervention in Langley Park that is based on the social-ecological perspective referred to above. The intervention, called Adelante, was developed with the theoretical understanding that if the substance abuse-related cluster is syndemic in nature, it calls for an intervention that addresses shared contributing factors as an integrated whole, not as analytically distinct factors that happen to occur within a community. The latter orientation reflects a tendency still dominant in public health, in which individual level theories and single, targeted interventions have been prioritized over comprehensive and context-relevant approaches. Trickett et al. (2011, p. 1411) have called this tendency a paradigm that “conceptualizes intervention as the importation and implementation of a specific evidence-based technology.” Even approaches labeled “community-based participatory research” often end up as arrangements in which a university or research organization teams up with community groups to conduct university-generated research or implement an intervention that originates with the university/research organization, and is not necessarily derived from or cognizant of community complexities.

Commensurate with the pattern, theoretical and intervention approaches to the prevention of youth risk behavior have generally not addressed the multiple, interacting contributing factors affecting Latino immigrant communities. The Adelante intervention, however, is specifically designed for this purpose. Public health approaches to this issue have thus far leaned heavily on an epidemiological framework, with a focus on correlations between risk factors and health behavior or outcomes, where risk factors are circumstances, individual characteristics, and exposures that are statistically significant precursors of negative behaviors and outcomes. Interventions following this framework seek to mitigate specified risk factors for behavior in a targeted manner similar to the mitigation of risk factors for a disease. Even though these focused “prevention science” approaches (Schwartz et al., 2007) within the public health arena have generated program models that demonstrate evidence of reducing specific risk factors, it was our view that such approaches still do not adequately capture or address the broader dynamics for immigrant Latino youth that occur at the community level, or address social ecologies contributing to health risk. That narrow focus raises questions about sustainability. Moreover, in the current research literature, substance abuse prevention studies have not generally focused on Latino adolescents (Goldbach, Thompson and Holleran-Steiker 2011), and most studies on family and neighborhood contexts of youth violence have not focused on Latino/Hispanic neighborhoods (Estrada-Martinez et al. 2013).

Yet within the social science and public health literature, there is research on youth who are at high risk for social and health problems pointing to common social determinants. This research includes; 1) the problem behavior syndrome literature (e.g., Jessor & Jessor 1997; Jessor, Donovan & Costa 1991) which has conceptualized youth with high levels of involvement in delinquency and health risk behavior as the consequence of exposure to multiple risk factors, and as sharing a perspective or worldview related to these risk behaviors; 2) research linking social/structural context, marginalization and risk behavior (Edberg & Bourgois 2013; Vigil 2007; Bourgois 2003/1996; Sampson & Wilson 1995; Edberg 2004; Wilson, 1987); and 3) research linking poor health and crime to shared community-level perceptions about a lack of capability and willingness to act in support of solutions (Sampson et al., 2005; Sampson, 2003). There have been efforts to address some of these gaps among Latino immigrants (Pantin et al 2003; Szapocznik & Coatsworth 1999), though these are still centered in the domains of family and school, as opposed to broader social and structural factors.

A multilevel community intervention based on a Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework was seen as a better way to address the broad community ecology of risk that underlies the co-occurring disparities for youth in Langley Park, which is driven by what Vigil (2007) calls “multiple marginalization.” In Langley Park, this includes; legal and documentation issues; language barriers; immigration politics and stigmatization; lack of access to resources, social support, and social capital; poverty; family and community fragmentation (in part due to the sequential nature of the migration process); mistrust and fear; and a generally low level of community efficacy (shared belief that the community can and will act to address problems). PYD approaches are part of a recent trend away from interventions that focus on negative precursors to health risk and delinquency among youth, instead concentrating more on asset-building and resilience. However, many youth programs use the term “positive youth development” and we did not want to apply this loosely. Even within this research literature, there are several interpretations of PYD and what it means for intervention (e.g., Catalano et al. 2012; the collection of PYD papers in the Journal of Adolescent Health, Volume 46, 2010; Catalano et al., 2004, vs. the approach expressed in Silbereisen & Lerner 2007; Lerner 2005; Lerner et al. 2005, Roth and Brooks-Gunn 2003). We have focused on the way in which the theoretical language of some PYD literature encompasses multiple levels of factors within a community, and most importantly, on the interaction between these levels as in a web, with the necessity of considering individuals-in-context -- a departure, as noted, from many of the prevention models in public health.

Thus a subset of PYD literature frames this as a focus on the person-context relationship (Schwartz et al., 2007; Scales et al., 2005; Theokas et al., 2005; Lerner et al., 2005). Application of this version of PYD is described in part as the “marshaling of developmental assets” within a community and around youth. This means that an intervention has to work at the level of context – what we refer to here as a social or community ecology -- where changing health outcomes for individual youth is a function of changes in that community ecology. Community-based programs are understood as having a role to play in such changes.

For these reasons, a key goal of the Adelante intervention was to develop and test a PYD-oriented intervention within a specific Latino immigrant community that did in fact attempt to foster a supportive person-context relationship. In practice, this means including in the intervention a mix of activities that focus on youth, parents/guardians, and community institutions and organizations, as well as on the connections between these community constituencies. Based on the data from the community definition research described here as well as the qualitative data from our previous intervention in the community, it also means inclusion of activities designed to increase youth and adult advocacy capabilities, which may in turn increase attachment to, and investment in, community. In addition, there was another key goal. Because there is a paucity of interventions described in the public health research literature that document effectiveness of this type of community intervention, the Adelante team felt that it was important to include a substantial research component so that we might contribute to filling that gap.

This is where the definition of community becomes important. In order to understand where to intervene (the extent of the community) and thus where to conduct the evaluation research, we first had to delineate community boundaries, both geographic and social. For intervention purposes, community boundaries inform decisions about the range of sites where intervention activities should be located, and social characteristics of the community that may have relevance for such activities. For data collection purposes, the boundaries determine the sampling area within which data have to be collected, since intervention effects are evaluated primarily at a community level. The Adelante intervention is being evaluated through multiple modalities: 1) a baseline and two follow-up in-person community surveys using a randomized cluster sampling design with an instrument carefully developed to use scales and measures adapted to the community and testing both mediating and outcome variables; 2) baseline and follow-up surveys of identified high risk cohorts parent/adult and youth dyads); 3) qualitative research on the experience of youth and community members with the program; and 4) extensive process data. It is also very important in this respect that the Adelante model was developed through a community collaboration, to respond to community-identified contributing factors, and is based on evidence from the same community to support its implementation and testing (from a previous intervention focusing only on youth violence prevention -- see Edberg et al., 2010).

Intervention Community

The intervention community is Langley Park, Maryland, typically defined as a census-designated place (CDP) comprising two Census tracts (8056, 8057) in Prince George’s County directly outside the District of Columbia. The comparison community is Culmore, in Northern Virginia. Culmore is demographically similar to Langley Park, though smaller in population.

Langley Park exemplifies a significant demographic change in Maryland, where there has been almost a 107% increase in Latino residents from 2000 (2010 U.S. Census). The recent Census shows a total community population of 17,262 with 79% self-classified as Hispanic – primarily from El Salvador and Guatemala, with smaller but significant percentages from Honduras, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. The central core area of the community is composed of dense, often crowded apartment complexes, surrounded by smaller duplexes and some single-family homes. In the previous intervention from 2005-2009, focusing on youth violence (called SAFER Latinos), the community was defined as Census tracts 8056.01, 8056.02, and 8057, all in Prince George’s County, MD (from the 2000 Census). However, the study team was aware that the more recent demographics had also changed the size and nature of the community, to where it exceeded the earlier boundaries and very likely spread beyond the earlier apartment building complexes into neighboring Montgomery County, MD and areas where there are single-family homes. Because the intervention and associated data collection is largely community-centric, not confined just to a defined cohort, understanding current boundaries was critical in defining a sample for data collection purposes and for delineating intervention boundaries and areas of focus. Finally, because Langley Park has had a reputation as a high crime area with other evident social problems such as alcohol abuse, the team was interested in obtaining data that would provide insight regarding the “social definition” and image of the community.

We did not initiate this process “cold,” without prior experience. The same university-community collaborative team has been involved in Langley Park since 2005, when a pilot intervention and precursor to Adelante, called SAFER Latinos, was developed and tested, focusing on youth violence prevention (this intervention ran from 2007 to 2009). From this study, we had already collected a base of qualitative data generated from the effort to identify factors contributing to violence, as well as from 14 focus groups conducted in the first two years of the research that were intended to assess and track community perceptions about violence, its causes, its relationship to other community factors, and possible solutions.

Those focus groups documented a community that was fragmented, sometimes dangerous, mistrustful related to a complex of immigration issues, and where social support was uneven, unlike some of the Central American communities of origin from which these immigrants came. There was a perception, for example, that other community members could not generally be relied on for help. In a focus group of young adult females (ages 18-24), one respondent, echoing a common view, said: “Sometimes we do need help but we don’t talk to our neighbors because nobody wants to help you and people are afraid to get involved because of the police and because of other things…in Langley Park, you could see somebody being killed but you won’t say anything to the police because you never know if the person that killed that person is nearby you and they may kill you if you give any information to the police.” People don’t help because “they are afraid to report it because the majority of us don’t have papers, don’t have documents.”

Similarly, a respondent in a young adult male group talked about limitations in obtaining help. “I think that if [this] person is involved in some sort of a religious group, then yes maybe they would help with the problem because there is help. But that if you aren’t involved with a religious organization then it is very difficult…for example, if you have an accident, that yes, that the majority would do this. That they would help and call the ambulance. But only up to there …and I understand because it is very hard economically and you just don’t have it. You only have enough to get by here and to maintain yourself.” The same respondent also explained one way in which the transnational nature of communities like Langley Park limits community support: “In Guatemala we have our families and we have to provide for our families, so we have to worry about our families in Guatemala and not worry so much about what is happening here.” Another young adult male said: “You don’t even know your neighbors sometimes, and if they don’t know you, they’re not going to help you.”

Support tended to come from close friend or family networks, not from a broader community. Moreover, differences of national origin as well as some subnational grouping hindered support networks. And, echoing what SAFER Latinos staff heard and saw, people were highly focused on working and meeting financial need, further hampering social support relationships, because – particularly for those that were undocumented – this typically required working two or even more jobs at minimum or less-than-minimum wage.

The lack of support extended to community and social services. A respondent from a parent/adult group said: “Well, what I don’t like about Langley Park is that there isn’t very much help for young kids. When a parent asks for help, there are not doors that are open. We need programs for those young kids…there is not a place where they can go and have a good time. There is not a big community center where kids can go.”

Along with lack of support, there were ubiquitous social problems, including alcoholism, violence, gangs, prostitution in apartment buildings, dirty conditions and poor housing. Young women in focus groups expressed concern about “all these people, especially men, telling you all these things in the street.” “[T]his is a different country and there are many people here from different countries. Some people look good, some look bad, you never know who you can talk to.” According to a parent group respondent, “The crime comes from drugs and alcoholism. So, that comes all together. So three factors that we do have that are bad in Langley Park are drugs, alcoholism, high crime. All that. All of those things all together make a package and put us at risk.” Common views about problems were accompanied by a sense that there was no power to do anything about them. Comments from one young adult group included the following: “I’ll distribute flyers to all the apartment but when it comes down to it, maybe two people will show up to it and others won’t. People just don’t show up.” Speaking of housing problems, one group participant said “The windows, the mildew, the rats, the floors are dirty. If you complain, they say, ”Maintenance has already been there and they’ve seen it and they know’…They don’t change it and they don’t fix it.” “I don’t think there’s someone that is capable or that feels capable of doing it.”

Thus, as we implemented the current Adelante community definition protocol, we began with a slightly earlier baseline of negative views about the community, though in these same focus groups it was also the case that most respondents valued the Latino small businesses and food available in Langley Park, and the fact that Spanish speakers were everywhere.

METHODS

The Adelante community definition research team included a public health doctoral student, an anthropology graduate student, and a research associate of the Avance Center, and was led by key university research staff and guided by the community partner organization.

The methods used for the community definition proceeded from a baseline map, then geo-mapping of selected service data to identify spatial distribution for Langley Park and potential new boundaries, followed by key informant interviews, observation, and intercept interviews with community residents. Intercept interviews are brief interviews conducted “on the spot” during observation and while engaged in targeted community walk-throughs. As a technique they are used in social marketing/communications research, and in marketing research, to reach respondents in their “lived spaces” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2002). The technique of ethnographic mapping has been used to address a number of domains, including the mapping of social networks and concepts. Our use is focused on identifying the spatial layout of a community and associated social identity(ies). Mapping in this sense has long been part of the “toolkit” for ethnographers, where the mapping of community space is defined by Cromley (1999: 55) as depicting “territory defined by the set of locations where the interactions of interest take place”, and generally useful wherever the spatial dimensions of a phenomenon are important. Ethnographic mapping has also been used for a variety of health related intervention purposes, typically to map the spatial distribution of HIV and other risk behaviors (e.g., Tripathi et al., 2010). In addition, ethnographic methods have generally been used in other efforts to define aspects of specific communities. Taplin and colleagues (2002), for example, utilized Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Procedures (REAP) to determine community relationships to a national park site; this included key informant interviews and “transect interviews” – the latter which are similar in some respects to the intersect interviews utilized for this study. More recently, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software has been used in conjunction with other ethnographic techniques for mapping spatial in conjunction with additional data (Brennan-Horley et al., 2010). And while qualitative techniques have been used to identify common definitions of the term “community” (MacQueen et al., 2001), we are using this approach to arrive at an emic definition of the subjective, “lived” physical and social boundaries of a named community.

This has added relevance for Langley Park because some of the usual markers for community are not available. For example, there is no zip code for Langley Park. It is, as noted, a Census Designated Place (CDP), and there is an established practice of using the designation “Langley Park” in signage, including on the freeway off-ramp for University Boulevard, one of the two main streets framing the community. Thus, while not an “imagined community” in Anderson’s sense (Anderson 1983), the geographically ambiguous community boundary sets the stage for a socially constructed (and contested) community definition.

Baseline Profile

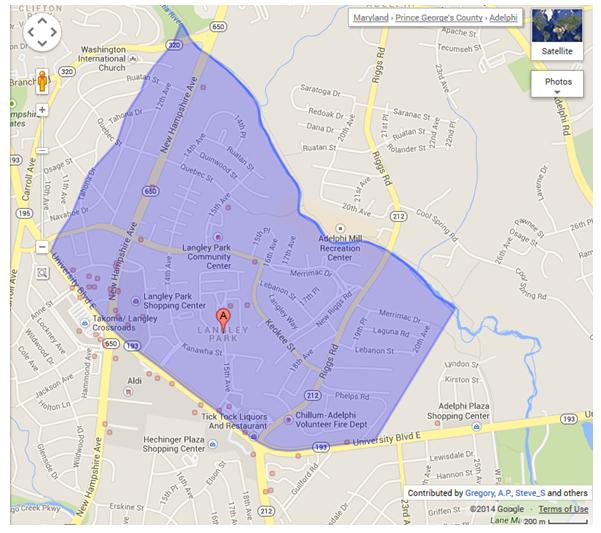

The research team began the definition process by using a basic Google map of the Langley Park Census-designated community. This map, shown in Figure 1, included the 2010 versions of the two Census tracts mentioned above (8056.01, 8056.02, 8057), and was similar to a Langley Park map used by a recent local coalition formed as part of the Prince George’s County Transforming Neighborhood Initiative (TNI), an effort by the County to coordinate resources in communities experiencing multiple social and health problems.

Figure 1. The 2010 CDP, Google Map Basic Area (Baseline Map.

In the earlier SAFER Latinos study, the sampled area was based on the 2000 delineation of these two Census tracts. However, some single family home blocks were excluded from the data collection because demographic data at the time suggested that the concentration of Latino residents was lower in those areas, and so for budget reasons, it was deemed a more productive use of interviewer time to focus on the concentrated community core.

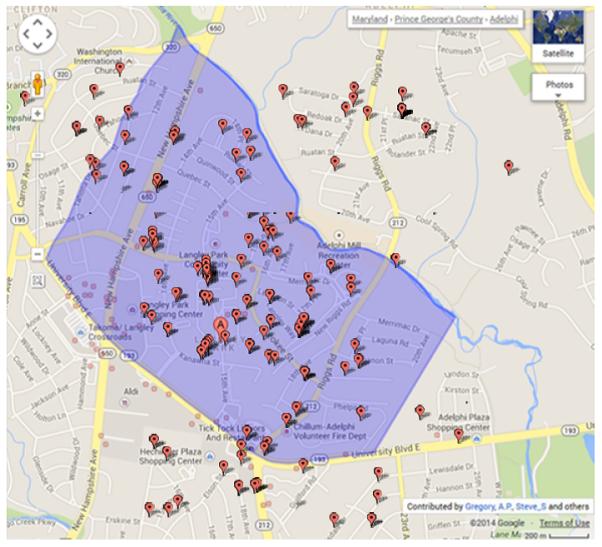

Second, we requested service utilization data from our key community partner, the Maryland Multicultural Youth Center (MMYC), specifically for individuals who received services at MMYC’s Langley Park office over the past 6 months, since MMYC provides a range of services to youth and families in the Langley Park area. Addresses for these individuals (with no other identifying information) were geo-mapped using BatchGeo software (www.batchgeo.com), providing a preliminary indication of areas beyond the basic Census tracts and TNI map that might need to be included in the definition. Figure 2 shows the map with these recent MMYC Langley Park clients, depicted in clusters based on residence (no individual locations shown).

Figure 2. The Geomapped Distribution of MMYC Langley Park Clients.

The geomapped service data clearly show client clusters beyond the CDP boundaries, particularly in areas south, northwest and northeast of the core CDP area. Moreover, clusters to the northwest are in Montgomery County, whereas Langley Park is commonly considered to be entirely within Prince George’s County. The clusters to the south touch on two other communities – Chillum to the west (left) and Adelphi to the east (right). Clusters to the northeast, predominantly from single-family homes, may reflect the designated catchment area for the high school attended by youth from Langley Park, which is actually located some distance from the community out in the direction of those clusters, along Riggs Road (closer to the high school this becomes Powder Mill Road).

Key Informant Interviews

The next step involved the conduct of key informant interviews with the MMYC Executive Director, the principal of the high school that draws most Langley Park youth, and 18 local apartment managers. Key informants were contacted by the MMYC Executive Director and Avance Center Director, based on their familiarity with a range of community leaders and organizations. These interviews used a semi-structured protocol designed to obtain input from community experts on: 1) the geographic boundaries of what is commonly considered Langley Park, ergo, the area that might be designated as a service area for the Adelante program; 2) important characteristics of the community; and 3) whether or not Langley Park was socially defined as an ethnic-based community, and if there were groups that were/were not considered within that definition.

Observation and Informal Street (Intercept) Interviews

Following those interviews, the community definition team used interim boundary maps based on the spatial distribution of MMYC Langley Park clients shown in Figure 2 as a guide for the next step – observation and informal intercept interviews. For the observation component, the team physically walked around both “core” (original Census tracts) and “boundary areas” (outside the original area, to include areas where client clusters were shown in the geomapping exercise), recording any details that could contradict, support, or augment the interim map, and noting specific kinds of community characteristics: apartment, multi-family or single family dwellings; stores/businesses; county location (Prince George’s or Montgomery); the presence of green space; and any other features that might serve to demarcate distinct spaces within Langley Park. As team members walked the neighborhood, they conducted a series of brief intercept interviews with residents in these areas, asking them if they identified as a resident of Langley Park, and asking for their views with respect to the geographic and social boundaries of the community, and recording perceived ethnic composition of the community. One interviewer conducted 54 street intercept interviews across multiple areas within the community – including areas viewed as bordering Langley Park and other communities. A second interviewer conducted 17 interviews in one border area (where there were Latino, African-American, Southeast Asian residents), and 45 interviews in a second border area. A third interviewer conducted 23 interviews, for an aggregate total of 139 interviews.

RESULTS

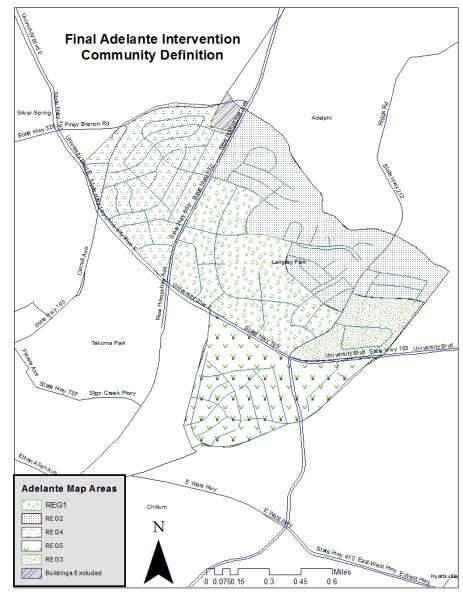

Results from the service client geo-mapping, the key informant interviews, observation, and community intercept interviews were then analyzed through simple coding for definitional consensus and common themes regarding social characteristics and social boundaries. A final community map was developed, shown in Figure 3. This map also includes five regions within the community, corresponding to interviewer descriptions of residential characteristics.

Figure 3. Final Map for the Adelante Intervention with Regions Identified.

Geographic Boundaries

The attached maps represent the geographic results of the community definition process (Figure 3 is the final version). The mapping process clearly reinforced initial assumptions that the Langley Park community was larger than its official Census designation. Key geographic differences from the original Census-based community definition are augmented by a zone system proposed by the ethnographic observation team in which the newly-defined community is divided into five areas.

The core apartment building area that formed the essence of the original Census tracts (8056.01 and 8056.02) is now called Area 1. This was the area used as the sampling boundary for the SAFER Latinos study.

For sampling purposes, several areas just east of the core apartment complexes were added. These areas are beyond the original SAFER Latinos survey sample boundaries, and are primarily single family homes (Area 2), yet still within the current Census tracts (part of 8057.00) for Langley Park. Residences from this area were added because there were Latino client clusters located there, and it is in easy walking distance from the core area. Some of these single family homes have multiple residents, and as such share some of the same constraints experienced by apartment building residents. From the interviews with apartment managers and additional data from residents of that area attending the local middle school, we estimate that single family homes have an average of 6 residents, where apartments range from 3-10 residents. Based on the team’s observation, we did not add in the areas farther east/northeast along Riggs Road, even though there were Latino client clusters from that area. These are single family homes, in a different Census tract, and not within walking distance of the Langley Park core. A likely reason for client clusters from this area is that they have heard of, or been connected to MMYC because, as noted, they are in the catchment area for the middle school and high school serving Langley Park. But these residences are far enough away from the core that they are not likely to have regular, day-to-day experience with the community.

Apartment complexes southeast of a main south-bordering avenue (Riggs Road) were now included and designated Area 3. These were not included within the original SAFER Latinos boundary for logistical reasons, but are still within Census tract 8057.00 and clearly within the area of regular interaction.

Based on geomapping and observation, multiple apartment buildings and single family homes on the northwest side of what used to be the upper boundary of New Hampshire Avenue are now included, together with some single family residences, and called Area 4. Residents here are primarily Latino. These areas straddle both Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties, in Census tracts 8057.00, 7020.00 and 7056.01, and thus extend beyond the CDP area. One apartment building was excluded from this zone because its residents were almost entirely elderly Caucasian and African-American.

Again based on the geomapping and observation, apartment buildings, single family homes and some condominiums south of Riggs Road, bordering on the area often referred to as Chillum, were added as Area 5, because of the apparent prevalence of Latino residents. These areas are in current Census tract 8055.00, outside the original CDP.

There was a substantial consensus among key informant and intercept interview respondents about the inclusion of these areas, even though there are several postal designations involved, and some areas are now in Montgomery County, whereas the original community definition was exclusively in Prince George’s County.

Designation of these areas was useful for the intervention and research because it 1) clarified differences in the sampling area from our previous work, as well as changed intervention coverage needs; and 2) provided information useful for determining outreach strategies. For example, if one area was characterized by condominiums as opposed to apartments (as in Area 5), centralized outreach and recruiting through building management contacts would not be possible – door-to-door work would likely be necessary. In Area 2, where there are single family homes, the Adelante staff have to make similar decisions about how to extend intervention activities where there is no centralized facility or common space.

Social Definition

The interview and observation data resulted in several key themes concerning the social boundaries and definition of Langley Park. Some of these data reinforce what we learned in the earlier qualitative data from SAFER Latinos. The discussion below is organized by key themes.

Lack of social support and social space

More than one community leader expressed the view that space is a problem in Langley Park, where the landscape is an amalgamation of strip malls with small businesses, unadorned brick apartment complexes and a smattering of small single family homes (at least some of which have multiple residents). There is a dearth of social services; residents must leave the community to access a clinic, child care, social services and often work. As one key informant noted, “you can shop, go out to eat or get liquor in Langley. That’s all.” And though Langley Park is anything but desolate, key informants said that residents were more likely to be found in the aisles of grocery stores and in laundromats rather than out on the streets. This is because Langley Park lacks viable space where the community can congregate for civic activities, let alone socialize – particularly for adolescents and young adults.

There is an existing community center, which does offer some activities, but these are fee-based. It is also described as including numerous administrative offices. Moreover, one key informant characterized program offerings there as geared more to the elderly and children, and deemed activities like pottery classes as “too WASPy.” Adolescents and young adults spend free time at, among other locations, a local McDonalds, congregating on sidewalks or outside of a small shopping center, where they are often told to stop loitering. Even at a strip mall called “La Union” (named after the city and region in El Salvador), the owner does not want people to gather or hang out there.

Most of the activities that attract adolescents and young adults are said to be in neighboring, and wealthier, Montgomery County, where a shopping mall, a community center with a basketball court and swimming pool, and several social service centers are located. From the key informant perspective, there is little incentive for youth to stay in Langley Park.

A local school official and key informant believed that the lack of a community sanctuary and safe gathering place led many Latino adolescents and young adults to find solidarity in gangs. Gangs, she said, “provide a false sense of community” for the youth. At the same time, she argued that gang activity has obstructed the growth of the Langley community for all others, and played a role in an unsuccessful attempt to build a new community center with funding from government agencies and a local Catholic archdiocese. Prominent gangs in Langley Park have included MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and 18th Street – the same gangs associated with the recent violence in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala from which the recent influx of migrant youth are fleeing.

Transience

Langley Park is often described in these interviews as a transient community with a constant influx of new immigrant residents. Key informants said that Langley Park is “the first stop on the immigrant trajectory” and “The Ellis Island of the U.S.,” and ultimately a community where there is “more isolation than connection.” Although in the Central American home countries there is a widespread belief that those who live in Langley Park “work in a Mecca,” the reality is that shortly after their arrival “people just walk away from Langley” – a pattern said to be common to both residents and community organizations.

Similarly, fluidity was a prominent theme in the intercept interview comments. Like the pattern for youth noted earlier with respect to recreation and mall locations, many social and other services used by Langley Park residents are not in Langley Park (Prince George’s County), but in close-by areas of Montgomery County, again because Montgomery County has more resources. The regular use of these services has created a “social flow” that moves back and forth from Langley Park, blurring community boundaries. According to one key informant, “the people of Langley don’t care if they are part of Prince George’s or Montgomery County”. In one interview, businesses in a Montgomery County area were designated as within Langley Park, while the residences in the same location were not – a clear recognition of that social flow.

Attachment to community

Community sentiment/attachment related to Langley Park appears to be mixed. On the one hand, it was described by key informants as a transient community, a first (and lowest) step on a potential trajectory of improvement. It is perhaps a community “not for what they [residents] communally share, but for what they lack”. At the same time, there also appears to be a relatively strong ethnic identification with Langley Park. In several intercept interview comments, Latino – specifically Central American -- respondents expressed a connection with Langley Park even though there is technically no postal zip code by that name, and residents’ zip codes may reflect the communities of Silver Spring, Takoma Park, Adelphi, or Hyattsville, all of which include or “border” the defined Langley Park community. One apartment manager in a southern border area said, for example, “They may not call me part of Langley Park, but I consider myself part of this area.” A resident in a northern border area said “My address may say Silver Spring, but I am a part of Langley Park”.

Attachment, however, may reflect generational differences. In several single family home areas that were within a newer bordering area, identification with the community differed between youth and adults, reflecting the categorization of Langley Park as a low-end or starter community for immigrants. While youth respondents from these areas typically felt connected to Langley Park because their peer social group was largely from there, adults in the same areas often distanced themselves, identifying themselves with the other nearby communities (Chillum or Takoma Park). Adults responding this way either rented or owned homes, and their responses suggested a self-identification as having moved beyond the lowest rung of a social trajectory. [One female intercept interview respondent from Puerto Rico said “No, I don’t live in Langley Park. I own my home”.] If so, this is powerful evidence of an enduring immigrant imaginary, played out in the fluid community context of Langley Park.

Racialized identity and exclusion

Even though Langley Park is primarily Latino, it does include smaller and thriving immigrant populations from other regions, including South Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia, as well as a small African-American population. From the viewpoint of Latino residents interviewed, however, the community definition was racialized and exclusive. In some of the border areas, the population is less concentrated Latino. Yet several Latino respondents specifically indicated that they did not view the African American or African residents as part of the Langley Park community, even if they live in the same geographic area. This attitude can also be seen in a recent community conflict between Latino and African-American community members over use of a recreational space near the center of the community. It is also very evident in multiple comments from the SAFER Latinos focus groups, in which participants consistently presented the relationship between African-Americans and Latinos as one of conflict, even in some cases claiming a bias in favor of African-Americans by teachers and police.

One key informant and head of a community organization cited a controversial scenario which she believed exemplified the transitory and fractured nature of the community, as well as ongoing racial dynamics: the failure to create a Latino-oriented multi-service community center in the mid-2000s. The planned center was to include amenities such as a health clinic, a Latin American youth center, a large gymnasium and a chapel. In partnership with the state, county and Federal government, the Washington D.C. Catholic Archdiocese pledged $6 million to build and fund the $11.8 million center. However, the land on which the center was to be built belonged to an organization that caters predominantly to African-American youth and related constituencies. The conflict that ensued was both racially and religiously charged, with particular emphasis on how the African-American community felt persecuted by Latino gangs (interestingly, the mirror image of common Latino perceptions). Despite acquiring adequate funding and support, the division between the African-American and Latino community prevented the establishment of the community center. The physical presence of “morenos” (African-Americans) and the growing community of African immigrants was acknowledged; however, respondents agreed, emphatically, that they were not part of their community.

A key informant spoke about how in prior years the streets were occupied by food vendors, “ladies selling pupusas” and food trucks offering “comida tipica,” which created an “open air community,” not a unlike Latin American market where families, friends and neighbors might have congregated in their home countries. However, gangs began to extort the vendors, demanding that food trucks pay a fee and that the ladies selling food “rent’ their street corners. Violence escalated and as a result the outdoor food vendors were forced to shut down, which she felt “was a great loss to the community.” [To be fair, possibly a more significant factor forcing out the food trucks was the implementation of a local policy requiring licenses and limiting the number of total food trucks through a lottery.]

Together, the defeat of the proposed community center and the decline of outdoor food vendors illustrated for this respondent how the factions within Langley Park, between African-American and Latino populations, and between gang and non-gang members, have suppressed community spirit and stymied positive social growth.

Recent changes

Some qualification may be necessary here. The views expressed by key informants and intercept interview respondents may not fully reflect changes now occurring in the community that have not yet settled into common knowledge. In recent years two initiatives, not even counting the Adelante project, have positively impacted the availability of services and support. One is a large grant to a well-known Latino advocacy organization that was able to renovate a building in the center of the community and offer a range of services in addition to the legal and advocacy activities. The second is the Prince George’s County TNI, which has been surprisingly robust in organizing local resources to address a number of community problems, and is responsible for a small, but brand-new multi-services center across the boulevard from the core community area. Finally, at some point in the next five years construction will begin on a light rail line that will pass immediately through Langley Park. This is likely to have significant social impact.

DISCUSSION

Despite increased support within public health for a social-ecological approach as a way to acknowledge the web of causal factors surrounding a given health problem, the methodological toolkit in public health is not yet adequately geared for such complexity. Clean tests of hypotheses, identification of dose-response metrics, and other analogies from biomedical research remain the analytical gold standard – biasing potential intervention models towards those that can be evaluated by such means. Communities, however, are messy, complex, and integrated phenomena, nested within structural, social, political economic and cultural environments. There remains a significant gap in thinking and methodology between the goal and reality of broader community interventions and the research that accompanies them. Anthropologists working in public health have an important role to play in closing this gap, by introducing methods to describe community dynamics and the implied “connectedness of causality.” and developing intervention models and accompanying evaluation research methodologies that do account for these dynamics.

The Adelante intervention is one such attempt, and the ethnographic community definition exercise – while a relatively limited effort – was part of that process. To address the syndemic nature of the targeted health disparities among Latino immigrant youth or any other population for that matter, it is important to collect a range of data that knit together elements of the community potentially shaping vulnerability as a foundation for intervention.

The multi-method, ethnographic approach described above provided a very useful foundation for defining the community in terms of sampling, data collection, and the conduct/location of intervention activities. These results also illuminated several important issues concerning the fluidity, mobility and social character of this community. Moreover, interview comments by adults in border areas strongly suggest identification of Langley Park as an initial step within an immigrant trajectory to the middle class that is still very much a part of the “immigrant imaginary”. The categorization as an initial step, however, means that the community is seen as lower in status, as the “bottom rung.” At the same time, we see that perceptions of social support from the community are generally low. Thus it is not surprising in this context, for example, that gangs may have at least an initial appeal as a social support network among youth; indeed; they are often talked about that way.

Second, while it may be common for residents in this marginalized setting to feel a low sense of efficacy with respect to addressing problems within the community, they readily take advantage of opportunities that exist outside of community boundaries to access better services, recreation and educational resources; hence the “social flow” between the primary location of Langley Park within Prince George’s County and surrounding areas in Montgomery County.

Third, the profound racial undercurrent that came out in several residents’ definition of Langley Park references a significant, though under-addressed dynamic. In interviews from the previous SAFER Latinos intervention we encountered these racial dynamics in community conflicts over access to public and private space. This also came up in focus groups and informal discussions with youth concerning gang formation at the high school and violence in the community in general, where racial identity was at least one element of gang membership, and violent crime in the community was often framed as “Black-on-Latino” crime. The ethnic identification that in one sense serves as a strength is, in this sense, a centrifugal force in the community, contributing to fragmentation and increasing the potential for conflict.

What do these characteristics say about the level of attachment to community, a factor that may affect the success of preventive interventions? This is an important question to pursue, because it may be the case that without some effort to bolster community connection, prevention efforts will not draw on a sufficient level of community motivation. This is particularly true if the intervention approach, such as the one used for Adelante, is based on community collaboration and the marshaling of community resources to build a more supportive environment for youth and thus reduce the likelihood of involvement in health risk behavior. Our data from the community definition process as well as from our experience working in this community since 2005 suggest strongly that there is a conflicted sense of attachment. The positive aspect relates primarily to the concentration of Latinos, Latino (specifically Central American) food and businesses, Catholic and evangelical protestant churches, and so on. At the same time, the negative aspect stems from an awareness that the community has multiple problems, including substance abuse, violence, housing, legal status, poverty, and work instability, and that there is not much most people can do about it, and in any case, when the opportunity comes many residents would prefer to move out. Yet our survey data show that there are now Latino residents who have lived there for more than 5, even 10 years, and in recent years more services and supports have begun to take root, including our own interventions.

Thus the community definition protocol provided initial data concerning the dimensions of identity in this concentrated immigrant community, where connections to community are contingent and linked to at least several dimensions: the instrumental utility of community connection or disconnection, which is in part a function of the resources and supports available in the community; the value of identity as a community member vis a vis a perceived immigrant trajectory and the community’s designated place in the hierarchy implied in that trajectory; and the ethnic/racial relations between groups in the community. Together, these suggest a need for social cohesion efforts and resource-building as part of community preventive interventions. These findings have been incorporated into several of the Adelante intervention strategies: 1) a focus on building an intervention identity that reflects youth and community aspirations (exemplified by a “turning the corner” theme in the Adelante logo, shown below in Figure 5); 2) the development of more systematic strategies for linking youth and adult programming to community organizations/actors through a Community Advisory Board to increase social capital and perceived support; and 3) multiple strategies, including social media, advocacy, and health literacy, to increase community efficacy and sense of attachment. There are measures in the community survey that capture some of these factors.

Figure 5. Adelante Logo.

In addition to the social identity, the community definition research results have been important for key methodological and operational reasons. The community sampling plan (see Cleary et al. 2014) serves as the basis for the survey sampling design which is the primary means by which intervention effects are measured. Moreover, in our project meetings with community partners, we use the region map as an ongoing guide to intervention coverage gaps – for current and planned intervention activities, we identify their actual or likely coverage areas using the map and try to ensure, over time, that we are able to reach all areas.

Finally, the community definition effort supports a general argument that health disparities cannot be effectively addressed simply by the application of decontextualized technologies, even if evidence-based, as if they are “plug-and-play” modalities. However, this argument requires ongoing evidence in order to gain traction in the corpus of programs recognized as effective within the public health field.

Figure 4. Langley Park.

REFERENCES CITED

- Anderson B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso; London: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003/1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Horley C, Luckman S, Gibson C, J Willoughby-Smith. GIS, Ethnography and Cultural Research: Putting Maps Back in to Ethnographic Mapping. The Information Society: An International Journal. 2010;26(2):92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary SD, Simmons L, Cubilla I, Andrade E, Edberg M. SAGE Research Methods Cases. SAGE Publications, Ltd; London, United Kingdom: 2014. Community Sampling: Sampling in an Immigrant Community. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/978144627305014529519. [Google Scholar]

- Cromley EK. Mapping Spatial Data. In: Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD, Trotter RT III, Cromley EK, Singer M, editors. Mapping Social Networks, Spatial Data, and Hidden Populations. Altamira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Bourgois P. Street Markets, Adolescent Identity and Violence: A Generative Dynamic. In: Rosenfeld R, Edberg M, Fang X, Florence CS, editors. Economics and Youth Violence: Crime, Disadvantage and Community. New York University Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Cleary S, Vyas A. A Trajectory Model for Understanding and Assessing Health Disparities in Immigrant/Refugee Communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010 Feb; doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9337-5. DOI 10.1007/s10903-010-9337-5 (on line) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Cleary S, Klevens J, Collins E, Leiva R, Bazurto M, Rivera I, Taylor A, Montero L, Calderon M. The SAFER Latinos Project: Addressing a Community Ecology Underlying Latino Youth Violence. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M. El Narcotraficante: Narcocorridos and the Construction of a Cultural Persona on the U.S. – Mexico Border. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Kreuter MW, editors. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Environmental Approach. 3rd ed Mayfield Publishing; Mountain View, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan J, Costa FM. Beyond Adolescence: Problem Behavior and Young Adult Development. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lerner J, Almerigi JB, Theokas C, Phelps E, Gestsdottir S, et al. Positive Youth Development, Participation in Community Youth Development Programs, and Community Contributions of Fifth Grade Adolescents: Findings from the First Wave of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:17–71. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scotti R, Blanchard L, Trotter RT. What is Community? An Evidence-Based Definition for Participatory Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–1938. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR., Jr. Effects of Differential Family Acculturation on Latino Adolescent Substance Abuse. Family Problems. 2006;55:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Jr, Eddy JM, DeGarmo DS. Preventing Substance Use Among Latino Youth. In: Bukoski WK, Sloboda Z, editors. Handbook of Drug Abuse Prevention: Theory, Science and Practice. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJ, Newman FL, Briones E, Prado G, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: The Efficacy of an Intervention to Increase Parental Investment in Hispanic Immigrant Families. Prevention Science. 2003;4(3):189–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1024601906942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. The Neighborhood Context of Well-Being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3, supplement):S53–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S. Social Anatomy of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(2):224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Wilson WJ. Race, Crime and Urban Inequality. In: Peterson JHR, editor. Crime and Inequality. Stanford University Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Scales PC, Foster KC, Mannes M, Horst MA, Pinto KC, Rutherford A. School-Business Partnerships, Developmental Assets, and Positive Outcomes among Urban High School Students: A Mixed-Methods Study. Urban Education. 2005;40:144–189. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Addressing the Challenges and Opportunities for Today’s Youth: Toward an Integrative Model and its Implications for Research and Intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28(2):117–144. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17(4):423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. AIDS and the Health Crisis of the Urban Poor: The Perspective of Critical Medical Anthropology. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;39(7):931–948. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. Pathways of Influence on Equity in Health. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An Ecodevelopmental Framework for Organizing the Influences on Drug Abuse: A Developmental Model of Risk and Protection. In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR, editors. Drug Abuse: Origins & Interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM. Family Psychology and Cultural Diversity: Opportunities for Theory, Research and Application. American Psychologist. 1993;48(4):400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin DH, Scheld S, Low SM. Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historical Park. Human Organization. 2002;61(1):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Theokas C, Almerigi JB, Lerner RM, Dowling EM, Benson PL, Scales PC, et al. Conceptualizing and Modeling Individual and Ecological Asset Components of Thriving in Early Adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Beehler S, Deutsch C, et al. Advancing the Science of Community-Level Interventions. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1410–1419. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi BM, Sharma HK, Pelto PJ, Tripathi S. Ethnographic Mapping of Alcohol Use and Risk Behaviors in Delhi. AIDS Behavior. 2010;14:S94–S103. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Making Health Communication Programs Work (Revised Edition) National Cancer Institute, National institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. A Model for Explaining Drug Use Behavior among Hispanic Adolescents. Drugs & Society. 1999;14(1-2):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil JD. The Projects: Gang and Non-Gang Families in East Los Angeles. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . The Ecological Framework. World Health Organization; Geneva: [accessed August, 2014]. www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en/ [Google Scholar]