Abstract

Background/Aims

Epidemiological data indicate that emotional stress and depression might influence the development of gastrointestianl disorders and cancers, but the relationship between the two is still unclear. The aim was to investigate the effect of stress/depression on the prevalence of digestive diseases. In addition, we tried to identify whether stress and depression are risk factors for these diseases.

Methods

A total of 23 698 subjects who underwent a medical check-up including upper and lower endoscopy were enrolled. By review -ing the subject’s self-reporting questionnaire and endoscopic findings, we investigated the digestive diseases, including functional dyspepsia (FD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), reflux esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, and adenoma and carcinoma of the stomach and colon. Stress and depression scores were measured by the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument and Beck’s Depression Inventory, respectively (Korean version).

Results

Stress and depression were related to FD, IBS, and reflux esophagitis. Depression was also linked to peptic ulcer disease and adenoma/carcinoma of the colon and stomach. Multivariate analysis revealed that stress and depression were independent risk factors for FD (OR, 1.713 and 1.984; P < 0.001) and IBS (OR, 1.730 and 3.508; P < 0.001). In addition, depression was an independent risk factor for gastric adenoma/carcinoma (OR, 4.543; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Stress and depression are related to various digestive diseases, and they may be predisposing factors for FD and IBS. Depression may also be a cause of gastric cancer. Psychological evaluation of gastroenterology patients may be necessary, but more study is needed.

Keywords: Depression; Dyspepsia; Irritable bowel syndrome; Stress, psychological

Introduction

Emotional stress and depression can down-regulate various parts of the immune system, which is located in both the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system, by influences on the principal effectors, such as neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, neurohormones and adrenal hormones.1 There have been many studies on the association between stress/depression and cancer. Cancer is a heterogeneous disease group with various causes, including chemical carcinogens, immunological, psychological, and behavioural factors.2–4 Previous studies have revealed that emotional stress can increase the risk of cancer.1,4,5 Also, the prevalence of depression among cancer patients is known to increase with disease severity and symptoms.1,4 However, the association between depression and subsequent cancer incidence is still unclear, although severe and chronic depression may be linked with elevated cancer risk.2,3

On the other hand, previous studies have shown that emotional stress and depression might influence the development of functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, such as functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).6–9 However, the association between the organic GI disorders and stress/depression is still unknown; except for a recent study, which reported that reflux esophagitis is associated with emotional stress.10

The aim of our study was to investigate the effect of stress and depression on the prevalence of digestive diseases, including FD, IBS, reflux esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and adenoma and carcinoma of the stomach and colon. In addition, we tried to identify whether stress and depression are risk factors for these diseases.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was based on the medical records of examinees who underwent upper and lower endoscopy at our center from January 2010 to March 2014. Subjects who did not answer the questionnaires and subjects who refused to undergo a biopsy were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Konkuk University School of Medicine which confirmed that the study was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration (KUH1010576). After the IRB approval, this study was registered in the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) (ID: KCT0001101). All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Questionnaires and Definitions

A self-reporting questionnaire was filled out by all the examinees. The questionnaire included the following items; underlying disease, medication history, history of malignant tumor, smoking, alcohol intake, the test for depression, the test for stress, symptoms of dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. Other than the questionnaires, the medical record data of the subject’s age, gender, height, and weight were reviewed.

The Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version (BEPSI-K) was used to measure the severity of stress.11 Depression was assessed using the Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory (K-BDI) scoring system.12 The BEPSI-K is a 5-item self-report questionnaire. The sum of the five items is divided by five for the final score, and a subject with a higher final score experiences more stress. There were 3 groups based on the final score; the score of 0 to 1.8 indicates a low level of stress; 1.8 to 2.8, moderate level of stress; and more than 2.8, high level of stress. Our study considered the total score of ≥ 2.4 as the high stress group.10,11 The BDI consists of 21 self-administered items with scores ranging from 0 to 63. The total score of 0 to 9 indicates no depression; 10 to 15, mild depression; 16 to 23, moderate depression; and 24 to 63, severe depression. We set the cut off value of 10 as positive for depression.

FD was defined as follows: One or more of the following symptoms occurred for more than 3 days per month in the last 3 months: (1) bothersome postprandial fullness, (2) early satiation, (3) epigastric pain, and (4) epigastric burning. Furthermore, there should be no evidence of any structural diseases that is likely to explain the symptoms on upper endoscopy. According to Rome III criteria, IBS was defined as follows: Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort occurred for more than 3 days per month in the last 3 months, associated with 2 or more of the following symptoms: (1) improvement with defecation, (2) onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and (3) onset associated with a change in form of stool. In addition, there should be no evidence of any structural diseases that are likely to explain the symptoms on colonoscopy. Heavy drinking was defined as consuming 15 drinks or more per week for men and 8 drinks or more per week for women.

Endoscopic and Histologic Findings

All examinees provided written consent to undergo the endoscopic procedures. We searched for the endoscopic records to identify the diseases which are capable of causing GI symptoms, such as gastric/duodenal ulcer, reflux esophagitis, and mass in the GI tract. In addition, the presence or absence of adenoma/carcinoma of the GI tract, chronic atrophic gastritis, and metaplastic gastritis was investigated through the endoscopic and histologic records.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as number (%). To analyze the association between depression/stress and digestive diseases, the data were compared using the Chi-square test and Student’s t test. Then, we performed logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for factors that independently caused the digestive diseases. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of Subjects

We identified 23 698 subjects (males 63.2%) during the study period. The overall mean age and body mass index (BMI) were 46.48 ± 10.50 (range, 17–91) years and 24.05 ± 3.17 (range, 12.18–62.39) kg/m2, respectively (Table 1). The number of subjects having a K-BDI score ≥ 10 was 1257 (5.4%, the depression group), and the number of subjects having a BEPSI-K score ≥ 2.4 was 2219 (9.4%, the high stress group). The number of subjects who belonged to both groups was 432 (1.8%). The questionnaire on K-BDI was not filled out by 423 subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All the Subjects (N = 23 698)

| Variables | Number (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 46.48 (10.50) | 45 (17–91) | |

| Male sex | 14 971 (63.2) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.05 (3.17) | 23.91 (12.18–62.39) | |

| ≥ 25 | 8391 (35.6) | ||

| ≥ 18.5 and < 25 | 14 529 (61.6) | ||

| < 18.5 | 650 (2.8) | ||

| K-BDI level | 2.23 (4.65) | 0 (0–46) | |

| ≥ 10 | 1257 (5.4) | ||

| BEPSI-K level | 1.53 (0.60) | 1.4 (0–5) | |

| ≥ 2.4 | 2219 (9.4) | ||

| K-BDI ≥ 10 and BEPSI-K ≥ 2.4 | 432 (1.8) | ||

| Past history of cancer | 510 (2.2) | ||

| Stomach or colon cancer history | 66 (0.3) | ||

| Smoking | |||

| Non-smoker | 10 088 (47.8) | ||

| Past smoker | 5720 (27.1) | ||

| Current smoker | 5277 (25.1) | ||

| Alcohol | |||

| Non-drinker | 4195 (18.5) | ||

| Social drinker | 17 499 (77.1) | ||

| Heavy drinker | 988 (4.4) | ||

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes | 1314 (5.5) | ||

| Hypertension | 3757 (15.9) | ||

| Congestive heart disease | 567 (2.4) | ||

| Stroke | 174 (0.7) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 3001 (12.7) | ||

| Medication | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 1277 (5.4) | ||

| Anticoagulant | 71 (0.3) | ||

| NSAID | 1185 (5.0) | ||

| Functional dyspepsia | 7156 (31.2) | ||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 5566 (26.8) | ||

| Colorectal adenoma and carcinoma | 5654 (23.9) | ||

| Adenoma | 5628 (23.7) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 26 (0.1) | ||

| Stomach adenoma and carcinoma | 92 (0.4) | ||

| Adenoma | 49 (0.2) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 43 (0.2) | ||

| Reflux esophagitis | 2978 (12.6) | ||

| Peptic ulcer disease | 830 (3.5) | ||

| Atrophic gastritis | 10 205 (43.1) | ||

| Metaplastic gastritis | 1589 (6.7) |

SD, standard deviation; K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory; BEPSI-K, the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

The number of subjects who had symptoms of FD was 12 935, and 5779 subjects were excluded due to abnormal findings on upper endoscopy, such as peptic ulcer disease, reflux esophagitis, advanced GI cancer, and post-operative state of the stomach. The number of subjects who had symptoms of IBS was 7968, and 2402 subjects were excluded due to abnormal findings on lower endoscopy, such as advanced GI cancer, post-operative state of the colon and rectum, suspicious or definite intestinal tuberculosis and inflammatory bowel disease, and other forms of infectious colitis. Finally, the number of subjects with FD and IBS was 7156 (31.2%) and 5566 (26.8%), respectively. Other baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

The High Stress Group and the Depression Group

Subjects with a high stress score were younger and more common among in men (Table 2). They showed a higher incidence of obesity, current smoking, social and heavy drinking, FD, IBS, reflux esophagitis, and NSAID medications. They also showed a lower incidence of antiplatelet medication. Meanwhile, subjects with depression were younger and had female predominance (Table 3). They showed a higher incidence of underweight, current smoking, FD, IBS, adenoma and carcinoma of the stomach, and NSAID medication. They also showed a lower incidence of reflux esophagitis, PUD, and colorectal neoplasia. Subjects who quit smoking and social drinkers were less likely to become depressed. Past history of cancer and underlying diseases was not linked with high stress and depression.

Table 2.

Comparison Between the High Stress Group and the Reference Group

| Variables | High stress group (n = 2219) | Reference group (n = 21 479) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)a | 43.84 (± 10.07) | 46.75 (± 10.51) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex (n [%]) | 1882 (84.8) | 13 089 (60.9) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 24.01 (± 3.16) | 24.45 (± 3.24) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 25 (n [%]) | 888 (40.3) | 7503 (35.1) | < 0.001 |

| < 18.5 (n [%]) | 60 (2.7) | 590 (2.8) | 0.993 |

| Past history of cancer (n [%]) | 36 (1.6) | 474 (2.2) | 0.081 |

| Smoking (n [%]) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-smoker | 621 (30.8) | 9467 (49.6) | |

| Past smoker | 599 (29.8) | 5121 (26.9) | |

| Current smoker | 793 (39.4) | 4484 (23.5) | |

| Alcohol (n [%]) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-drinker | 211 (9.8) | 3984 (19.4) | |

| Social drinker | 1792 (83.1) | 15 707 (76.5) | |

| Heavy drinker | 154 (7.1) | 834 (4.1) | |

| Comorbidity (n [%]) | |||

| Diabetes | 142 (6.4) | 1172 (5.5) | 0.069 |

| Hypertension | 327 (14.7) | 3430 (16.0) | 0.136 |

| Congestive heart disease | 57 (2.6) | 510 (2.4) | 0.564 |

| Stroke | 17 (0.8) | 157 (0.7) | 0.808 |

| Dyslipidemia | 302 (13.6) | 2699 (12.6) | 0.158 |

| Medication (n [%]) | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 86 (3.9) | 1191 (5.5) | < 0.001 |

| Anticoagulant | 5 (0.2) | 66 (0.3) | 0.682 |

| NSAID | 155 (7.0) | 1030 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| K-BDI level ≥ 10 (n [%]) | 432 (20.5) | 825 (3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Digestive diseases (n [%]) | |||

| Functional dyspepsia | 1043 (48.2) | 6113 (29.4) | < 0.001 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 918 (46.5) | 4648 (24.7) | < 0.001 |

| Colorectal adenoma and carcinoma | 513 (23.1) | 5141 (23.9) | 0.402 |

| Stomach adenoma and carcinoma | 13 (0.6) | 79 (0.4) | 0.147 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 352 (15.9) | 2626 (12.2) | < 0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 79 (3.6) | 751 (3.5) | 0.862 |

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by the Student’s t test. All other data were presented as number (%) and analyzed by the Chi-square test.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory.

Table 3.

Comparison Between the Depression Group and the Reference Group

| Variables | Depression group (n = 1257) | Reference group (n = 22 018) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)a | 44.85 (±11.33) | 46.53 (±10.39) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex (n [%]) | 720 (57.3) | 7769 (35.3) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 23.47 (±3.50) | 24.09 (±3.13) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 25 (n [%]) | 378 (30.2) | 7861 (35.9) | < 0.001 |

| < 18.5 (n [%]) | 70 (5.6) | 564 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Past history of cancer (n [%]) | 25 (2.0) | 472 (2.1) | 0.830 |

| Smoking (n [%]) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-smoker | 599 (54.4) | 9271 (47.2) | |

| Past smoker | 179 (16.3) | 5477 (27.9) | |

| Current smoker | 323 (29.3) | 4876 (24.8) | |

| Alcohol (n [%]) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-drinker | 246 (20.8) | 3834 (18.2) | |

| Social drinker | 864 (73.0) | 16387 (77.6) | |

| Heavy drinker | 73 (6.2) | 891 (4.2) | |

| Comorbidity (n [%]) | |||

| Diabetes | 77 (6.1) | 1190 (5.4) | 0.277 |

| Hypertension | 185 (14.7) | 3486 (15.8) | 0.301 |

| Congestive heart disease | 38 (3.0) | 513 (2.3) | 0.122 |

| Stroke | 7 (0.6) | 163 (0.7) | 0.608 |

| Dyslipidemia | 162 (12.9) | 2775 (12.6) | 0.763 |

| Medication (n [%]) | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 79 (6.3) | 1178 (5.4) | 0.156 |

| Anticoagulant | 1 (0.1) | 70 (0.3) | 0.186 |

| NSAID | 106 (8.4) | 1053 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| BEPSI-K level ≥ 2.4 (n [%]) | 432 (34.4) | 1672 (7.6) | < 0.001 |

| Digestive diseases (n [%]) | |||

| Functional dyspepsia | 829 (66.6) | 6327 (29.7) | < 0.001 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 714 (65.3) | 4844 (25.0) | < 0.001 |

| Colorectal adenoma and carcinoma | 241 (19.2) | 5375 (24.4) | < 0.001 |

| Stomach adenoma and carcinoma | 12 (1.0) | 78 (0.4) | 0.003 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 120 (9.5) | 2769 (12.6) | 0.002 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 30 (2.4) | 768 (3.5) | 0.042 |

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by the Student’s t test. All other data were presented as number (%) and analyzed by the Chi-square test.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; BEPSI-K, the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version.

Association Between Stress/Depression and Digestive Diseases

Logistic regression analysis revealed that stress and depression were independent risk factors for FD (OR, 1.713; 95% CI, 1.526–1.923; P < 0.001 and OR, 1.984; 95% CI, 1.705–2.309; P < 0.001) and IBS (OR, 1.730; 95% CI, 1.539–1.945; P < 0.001 and OR, 3.508; 95% CI, 3.005–4.096; P < 0.001) (Table 4). In addition, FD was significantly more common in younger subjects, females, current smokers, and subjects having lower body weight. IBS was significantly more common in younger subjects, current smokers, subjects having lower body weight, and subjects who took a NSAID medication.

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses of the Predictors of Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| FD | K-BDI level ≥ 10 | 4.726 (4.186–5.336) | < 0.001 | 1.984 (1.705–2.309) | < 0.001 |

| BEPSI-K level ≥ 2.4 | 2.233 (2.041–2.441) | < 0.001 | 1.713 (1.526–1.923) | < 0.001 | |

| IBS | 6.619 (6.185–7.084) | < 0.001 | 5.668 (5.267–6.101) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 0.982 (0.980–0.985) | < 0.001 | 0.994 (0.990–0.997) | < 0.001 | |

| Female sex | 1.288 (1.216–1.364) | < 0.001 | 1.282 (1.179–1.394) | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index | 0.954 (0.945–0.963) | < 0.001 | 0.973 (0.961–0.984) | < 0.001 | |

| Current smoker | 1.185 (1.109–1.268) | < 0.001 | 1.188 (1.090–1.294) | < 0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 0.783 (0.723–0.848) | < 0.001 | |||

| NSAID | 1.148 (1.013–1.302) | 0.031 | |||

| IBS | K-BDI level ≥ 10 | 5.646 (4.965–6.421) | < 0.001 | 3.508 (3.005–4.096) | < 0.001 |

| BEPSI-K level ≥ 2.4 | 2.638 (2.401–2.900) | < 0.001 | 1.730 (1.539–1.945) | < 0.001 | |

| FD | 6.619 (6.185–7.084) | < 0.001 | 5.681 (5.276–6.116) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 0.965 (0.962–0.968) | < 0.001 | 0.970 (0.966–0.974) | < 0.001 | |

| NSAID | 1.263 (1.103–1.445) | 0.001 | 1.238 (1.049–1.461) | 0.012 | |

| Body mass index | 0.962 (0.953–0.972) | < 0.001 | 0.983 (0.972–0.995) | 0.004 | |

| Current smoker | 1.356 (1.262–1.457) | < 0.001 | 1.154 (1.061–1.255) | 0.001 | |

| Female sex | 1.146 (1.075–1.221) | < 0.001 | |||

| Drinker (social + heavy) | 1.259 (1.157–1.371) | < 0.001 | |||

| Past history of cancer | 0.772 (0.617–0.968) | 0.025 | |||

| Diabetes | 0.721 (0.621–0.836) | < 0.001 | |||

| Hypertension | 0.714 (0.653–0.782) | < 0.001 | |||

| Stroke | 0.535 (0.345–0.830) | 0.005 | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 0.750 (0.647–0.869) | < 0.001 | |||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; FD, functional dyspepsia; K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory; BEPSI-K, the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

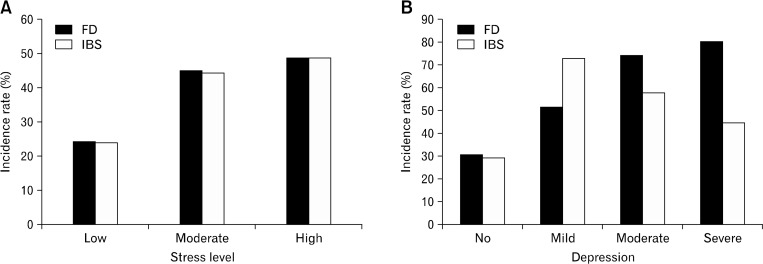

The incidence rates of FD and IBS according to the severity of stress and depression are shown in Figure. The incidence rates of FD and IBS increased along with the stress level. And the incidence rates of FD increased as the severity of depression increased. However, the incidence rates of IBS were highest among the subjects having mild depression.

Figure.

The incidence rates of functional gastrointestinal disorders according to the severity of stress and depression. The incidence rates of FD and IBS increase as the stress level increases (A). As the depression becomes more severe, the incidence rate of FD increases. However, the incidence rate of IBS was higher in the subjects with mild depression than in those with severe depression (B). The BEPSI-K score of < 1.8 indicates a low level of stress; 1.8 ≤ to < 2.8, a moderate level of stress; and ≥ 2.8, a high level of stress. The K-BDI score of 0 to 9 indicates no depression; 10 to 15, mild depression; 16 to 23, moderate depression; and 24 to 63, severe depression. K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory; BEPSI-K, the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version; FD, functional dyspepsia; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Old age (≥ 50 years), male sex, obesity, smoking, heavy drinking, and atrophic or metaplastic gastritis were independent risk factors for colonic adenoma and carcinoma (Table 5). In the multivariate analysis, stress and depression were found to have no significant relationship with colonic neoplasia. Depression was an independent risk factor for stomach adenoma and carcinoma (OR, 4.543; 95% CI, 2.415–8.549; P < 0.001). In addition, old age (≥ 50 years), smoking, and atrophic or metaplastic gastritis were also associated with stomach neoplasia.

Table 5.

Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses of the Predictors of Colonic and Stomach Neoplasia (Adenoma and Darcinoma)

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Colonic neoplasia | Age ≥ 50 years | 2.583 (2.430–2.746) | < 0.001 | 2.507 (2.338–2.689) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 2.090 (1.954–2.235) | < 0.001 | 1.699 (1.540–1.875) | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 1.575 (1.481–1.674) | < 0.001 | 1.325 (1.236–1.420) | < 0.001 | |

| Smoker (past + current) | 1.831 (1.714–1.955) | < 0.001 | 1.317 (1.206–1.438) | < 0.001 | |

| Heavy drinker | 2.122 (1.860–2.421) | < 0.001 | 1.540 (1.327–1.787) | < 0.001 | |

| Atrophic or metaplastic gastritis | 1.672 (1.574–1.777) | < 0.001 | 1.331 (1.241–1.427) | < 0.001 | |

| K-BDI level ≥ 10 | 0.734 (0.636–0.848) | < 0.001 | |||

| Stomach neoplasia | Age ≥ 50 years | 12.626 (6.722–23.714) | < 0.001 | 9.633 (4.919–18.868) | < 0.001 |

| Smoker (past + current) | 2.510 (1.539–4.094) | < 0.001 | 2.942 (1.759–4.919) | < 0.001 | |

| Atrophic or metaplastic gastritis | 10.667 (5.163–22.038) | < 0.001 | 6.611 (3.018–14.483) | < 0.001 | |

| K-BDI level ≥ 10 | 2.711 (1.472–4.992) | 0.001 | 4.543 (2.415–8.549) | < 0.001 | |

| Male sex | 2.246 (1.355–3.723) | 0.002 | |||

| Heavy drinker | 2.834 (1.462–5.490) | 0.002 | |||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

In colonic neoplasia, the following parameters were excluded from the analysis, because the P-values from the Chi-square test were more than 0.05; BEPSI-K level ≥ 2.4 (P = 0.402), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (P = 0.863), past history of cancer (P = 0.171), past history of stomach or colon cancer (P = 0.147). In stomach neoplasia, the following parameters were excluded from the analysis, because the P-values from the Chi-square test were more than 0.05; BMI ≥ 25 (P = 0.587), BEPSI-K level ≥ 2.4 (P = 0.147), NSAID (P = 0.631), past history of cancer (P = 0.452), past history of stomach or colon cancer (P = 0.227).

Male sex, obesity, current smoking, and younger age were independent risk factors for reflux esophagitis (Table 6). Male sex, obesity, current smoking, old age, NSAID medication, and atrophic/metaplastic gastritis were independent risk factors for PUD. Subjects with depression had less reflux esophagitis and PUD, and subjects with high stress had more reflux esophagitis. However, after multivariate analysis, reflux esophagitis and PUD were not related with stress/depression.

Table 6.

Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses of the Predictors of Reflux Esophagitis and Peptic Ulcer Disease

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Reflux esophagitis | Male sex | 2.964 (2.689–3.267) | < 0.001 | 2.403 (2.140–2.698) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 1.679 (1.553–1.814) | < 0.001 | 1.406 (1.290–1.533) | < 0.001 | |

| Current smoker | 1.962 (1.802–2.137) | < 0.001 | 1.430 (1.302–1.570) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 0.993 (0.989–0.996) | < 0.001 | 0.995 (0.990–0.999) | 0.013 | |

| Heavy drinker | 1.458 (1.231–1.728) | < 0.001 | |||

| K-BDI level ≥10 | 0.734 (0.605–0.889) | 0.002 | |||

| BEPSI-K level ≥2.4 | 1.354 (1.199–1.528) | < 0.001 | |||

| PUD | NSAID | 1.978 (1.550–2.523) | < 0.001 | 2.080 (1.589–2.721) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.026 (1.020–1.033) | < 0.001 | 1.042 (1.035–1.050) | < 0.001 | |

| Current smoker | 2.016 (1.732–2.347) | < 0.001 | 1.789 (1.509–2.122) | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index | 1.087 (1.065–1.109) | < 0.001 | 1.068 (1.042–1.094) | < 0.001 | |

| Male sex | 2.079 (1.762–2.453) | < 0.001 | 1.718 (1.399–2.110) | < 0.001 | |

| Atrophic/metaplastic gastritis | 0.650 (0.564–0.749) | < 0.001 | 0.500 (0.424–0.590) | < 0.001 | |

| Heavy drinker | 1.852 (1.412–2.429) | < 0.001 | |||

| K-BDI level ≥ 10 | 0.677 (0.468–0.979) | 0.038 | |||

| Antiplatelet agent | 1.875 (1.474–2.384) | < 0.001 | |||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; K-BDI, Korean version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory; BEPSI-K, the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version; PUD, peptic ulcer disease.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed and the significant results are highlighted in bold.

In peptic ulcer disease, the following parameters were excluded from the analysis, because the P-values from the Chi-square test were more than 0.05; BEPSI-K level ≥2.4 (P = 0.862), anticoagulant (P = 1.000).

Discussion

Stress and depression were independent risk factors for FD and IBS in our large-scale population-based study, and this finding was consistent with that in several previous studies.6–9 This association is probably derived from mutual and reciprocal interactions between the brain and the gut.8,13 Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a major mediator of the stress response in the brain-gut axis, can increase intestinal permeability and lead to FD and IBS. In addition, serotonin and the serotonin transporters, which assist the modulation of feelings and behavior such as anxiety and depression, can be associated with brain-gut function in functional GI disorders. In our study, the incidence rates of FD and IBS increased as the stress level increased, and the incidence rate of FD increased as the depression became more severe. However, as shown in Figure, the incidence rate of IBS was higher in the subjects with mild depression than in those with severe depression. To date, the relationship between the severity of depression and IBS has been unclear, and our result shows that IBS is related more with mild depression than with severe depression. In addition, this result indirectly demonstrates that FD and IBS have a different pathophysiology.

Our study revealed that depression was an independent risk factor for gastric adenoma and carcinoma. This result shows that depression may be linked with elevated stomach cancer risk. Changes of eating habits or life style due to depressive symptoms might affect development of gastric tumor. This may be an indirect cause of developing gastric tumor in depressed patients. However, depression can also directly cause gastric cancer. Previous studies revealed that the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in patients with depression probably impairs the immune system and contributes to the development of cancer.1,2 However, depression was not a predictor of colonic neoplasia in our study; this is probably because of the high incidence of tiny colon adenoma and the relatively very small number of colon cancer. On the other hand, there was no association between emotional stress and GI cancer incidence.

A recent study showed that reflux esophagitis is associated with emotional stress.10 In our study, reflux esophagitis was not only associated with emotional stress, but also with depression. However, stress and depression were not independent risk factors for the disease. In general, patients with high stress have unhealthy lifestyles as observed in our results. Therefore, without directly triggering esophagitis, emotional stress might be associated with the disease due to bad lifestyle habits, including smoking and weight gain. It is unclear why the subjects with depression had lower incidence of reflux esophagitis. One of the reasons for this is probably that the subjects with depression were less obese.

According to the results of our study, stress and depression were not independent risk factors for PUD. Excessive stress is known as one of the causes of PUD; however it does not mean that subjects having high stress suffered more from PUD. In addition, Korea is one of the highest endemic areas for H. pylori infection. Because of the high incidence of H. pylori-related ulcer, the incidence of stress-induced ulcer may be relatively low and it seems likely that this is one of the factors that influence the outcome. Subjects in the high stress group and depression group, and IBS patients took a NSAID medication more frequently in our study. We think that this is because the subjects who took a NSAID often had a chronic illness or pain. Chronic illness and chronic pain can be associated with emotional stress and depression, and IBS patients frequently have chronic visceral pain.14–16

Our study showed that drinking and smoking are closely associated with stress and depression. It is interesting that people who had stopped smoking and social drinkers were among the most infrequently depressed. On the other hand, non-smokers and non-drinkers were the least likely to be stressed.

This study has several limitations. First, the chronicity of stress and depression was not evaluated, because the assessment was performed only once. To show an association of stress and depression with cancer, several assessments over a long period are needed. Second, there were some missing values. BMI, smoking, drinking, and depression status were not measured in 128, 2613, 1016, and 423 subjects, respectively. In addition, the number of subjects who did not answer the questionnaire survey on FD and IBS was 767 and 2940, respectively. However, most of the examinees filled out the survey properly, and we excluded these missing data from the analysis process. Third, it is well known that IBS is significantly associated with anxiety disorders.17 However anxiety symptoms were not evaluated because it was not included in our questionnaire. In addition, the definition of FD was not entirely compatible with Rome III criteria and the subtype of FD and IBS was not evaluated. These are the limitations of a retrospective study. Fourth, H. pylori infection, the most powerful risk factor for PUD, was not included in the analysis, because the subjects who were examined for H. pylori infection accounted for only a small proportion of the total subjects. Fifth, depression and cancer can influence each other. The prevalence of depression among cancer patients is known to increase with disease severity and symptoms. In our study, however, most of gastric cancers were found in early stage and the patients had no cancer-related symptoms. In addition, the survey for depression was done before the cancer was diagnosed. Therefore there is a very little likelihood that the cancer causes depression. Sixth, the percentage of the population with symptoms of functional GI disorders was relatively high in our study. This may be because the baseline characteristics of our subjects differ from that of the general public. The population that has regular medical checkups of their own accord is in relatively good health. However they tend to be also very concerned about their health and some of them have checkups when the symptoms occur. Seventh, we did not consider the medication history of individuals which might affect the severity of stress and depressive symptoms, such as antidepressant and antipsychotic medications. In spite of the limitations, this large-scale study offers many insights into the relationships between stress, depression and the digestive diseases.

In conclusion, emotional stress and depression are related to many different digestive diseases, and they are independent risk factors for FD and IBS. Therefore, the evaluation of mental state may help to assess the patients with GI symptoms, especially patients with symptoms of FD or IBS. Depression may be a cause of gastric cancer; hence gastric cancer screening in depressed patients might be necessary. However, further studies are required to confirm the results.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Sang Pyo Lee, study concept, design, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript; In-Kyung Sung, study concept, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript; and Jeong Hwan Kim, Sun-Young Lee, Hyung Seok Park, and Chan Sup Shim, acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

ORCID: In-Kyung Sung, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3848-5571; Sang Pyo Lee, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4495-3714.

References

- 1.Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:617–625. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:269–282. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garssen B. Psychological factors and cancer development: evidence after 30 years of research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:315–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:240–248. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou N, Zhang X, Zhao L, et al. A novel chronic stress-induced shift in the Th1 to Th2 response promotes colon cancer growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak AD, Wu JC, Chan Y, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Lee S. Dyspepsia is strongly associated with major depression and generalised anxiety disorder - a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:800–810. doi: 10.1111/apt.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devanarayana NM, Mettananda S, Liyanarachchi C, et al. Abdominal pain-predominant functional gastrointestinal diseases in children and adolescents: prevalence, symptomatology, and association with emotional stress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:659–665. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182296033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanuytsel T, van Wanrooy S, Vanheel H, et al. Psychological stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone increase intestinal permeability in humans by a mast cell-dependent mechanism. Gut. 2014;63:1293–1299. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De la Roca-Chiapas JM, Solís-Ortiz S, Fajardo-Araujo M, Sosa M, Córdova-Fra T, Rosa-Zarate A. Stress profile, coping style, anxiety, depression, and gastric emptying as predictors of functional dyspepsia: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song EM, Jung HK, Jung JM. The association between reflux esophagitis and psychosocial stress. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank SH, Zyzanski SJ. Stress in the clinical setting: the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument. J Fam Pract. 1988;26:533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33:825–830. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salama-Hanna J, Chen G. Patients with chronic pain. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97:1201–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bras M, Dordević V, Gregurek R, Bulajić M. Neurobiological and clinical relationship between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larauche M, Mulak A, Taché Y. Stress-related alterations of visceral sensation: animal models for irritable bowel syndrome study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:213–234. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651–660. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0502-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]