Abstract

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are associated with insufficient functional β-cell mass. Understanding intracellular signaling pathways associated with this decline is important in broadening our understanding of the disease and potential therapeutic strategies. The hypoxia inducible factor pathway (HIF) plays a critical role in cellular adaptation to hypoxic conditions. Activation of this pathway increases expression of numerous genes involved in multiple cellular processes and has been shown to impact the regulation of β-cell function. Previously, deletion of HIF-1α or HIF-1β in pancreatic β-cells, as well as constitutive activation of the HIF pathway in β-cells, was shown to result in glucose intolerance and impaired insulin secretion. The objective of this study was to delineate roles of HIF-2α overexpression in pancreatic β-cells in vivo. We overexpressed HIF-2α in pancreatic β-cells by employing the Cre-loxP system driven by the Pdx1 promoter to delete a stop codon. Our study revealed that pancreatic HIF-2α overexpression does not result in significant differences in glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity or β-cell area compared to wild-type littermates under basal conditions or after high fat diet. Together, our study shows excess HIF-2α in the pancreatic β-cells does not play a significant role in β-cell function and glucose homeostasis.

Keywords: Hypoxia inducible factor β cell glucose homeostasis diabetes mellitus pancreas

Abbreviations

- ARNT

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- EPAS1

endothelial PAS domain protein 1

- GLUT1

glucose transporter 1

- GTT

glucose tolerance test

- HFD

high fat diet

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1 α

- HIF-1β

hypoxia inducible factor-1 β

- HIF-2α

hypoxia inducible factor-2 α

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- ITT

insulin tolerance test

- OE

overexpression

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

- WT

wild-type

Introduction

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway is critical for cellular adaptation and survival in response to hypoxia. Activation of this pathway increases the expression of numerous genes that are involved in multiple cellular processes such as angiogenesis, energy metabolism, apoptosis, and proliferation.1-4 HIFs belong to the basic helix-loop-helix PAS (Per-ARNT (aryl-hydrocarbon-receptor nuclear translocator)-SIM) family of transcription factors.5,6 In its active form, HIFs are heterodimers consisting of an oxygen-sensing α subunit and constitutively expressed β subunit. Regulation of this pathway under normoxic conditions targets the HIF-α subunit for degradation by the 26S proteasome. The HIF-α subunit becomes ubiquitinated by von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein and is subsequently degraded via proteosomal degradation.7-9

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease hallmarked by impaired glucose homeostasis and all types of diabetes are associated with an insufficient functional β cell mass. Recent research has suggested a role for HIF signaling in diabetes pathogenesis. HIF-1β, also commonly known as aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), was deleted in mice specifically in β cells and these mice had glucose intolerance, a defect in glucose stimulated insulin secretion and changes in gene expression in islets that mimicked those seen in patients with type 2 diabetes.10 Additionally, another study showed increased HIF-1β expression in hypoglycemic islets and showed HIF-1β plays a role in β cell metabolic signaling.11 Another study in mice reported that the deletion of HIF-1α in β cells results in impaired insulin secretion and reduced expression of glycolytic genes.12 These findings suggested that activation of the HIF pathway could potentially lead to diabetes protection. Interestingly, however, we and others have reported that constitutive activation of HIF-1α, via deletion of VHL in β cells, also results in impaired glucose sensing and glucose stimulated insulin secretion.13-16 While VHL signaling is complex and could have numerous effects in the β cell, these studies collectively suggest that both loss and constitutive activation of the HIF pathway leads to β cell dysfunction, however the specific role of HIF-2α, also known as endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), in regulating β cell function and glucose homeostasis is unknown.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α are structurally similar sharing an amino acid identity of 48% overall17-19 and like HIF-1α, HIF-2α is tightly regulated by VHL and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been shown to increase expression of hypoxic response genes.8,9,17 Although expression of some target genes, such as GLUT1 and VEGF, are common to both HIF-1α and HIF-2α, each also have a unique set of target genes which contribute to their functions in numerous processes including proliferation and apoptosis. Initial studies suggested HIF-2α activity was restricted to endothelial cells, but it has since been reported that HIF-2α expression is much more widespread, including but not limited to hepatocytes, pancreas interstitial cells, kidney fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes.20,21 While HIF-2α has been detected in human islets, the expression of HIF-2α in mouse islets is less clear. A number of studies have not been able to detect HIF-2α in mouse islets.reviewed in 22 However a report by Gunton et al.10 showed detection of HIF-2α mRNA in mice lacking ARNT in β cells which suggest that HIF-2α can be upregulated under certain conditions.

While HIF-1α has been extensively examined in energy regulation and glucose homeostasis, less is known about the specific role of HIF-2α. Previously, it was reported that HIF-2α expression in the hypothalamus was responsible for regulation of hypothalamic glucose sensing.23 Loss of HIF-2α in the proopiomelanocortin expressing-neurons of the hypothalamus led to impaired glucose sensing, increased food intake and ultimately increased body weight.23 In hepatocytes, constitutive expression of HIF-2α suppressed gluconeogenesis and enhanced hepatic insulin signaling.24 In macrophages, overexpression of HIF-2α improved insulin resistance in adipocytes.25 To our knowledge the specific in vivo role of HIF-2α overexpression in β cells has not been identified to date. In the present study, we used a tissue specific approach to overexpress HIF-2α in pancreatic β cells to determine its role in glucose homeostasis under basal conditions and during metabolic challenge by high fat diet (HFD) feeding. We generated mice that overexpress HIF-2α in β cells through deletion of a stop codon using the Cre-loxP system under the Pdx1 promoter driven cre expression. Our study revealed that HIF-2α overexpression in β cells does not alter body weight, random or fasting blood glucose nor did it result in any significant differences in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity, suggesting that the overexpression of HIF-2α in β cells does not alter glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis under basal or diabetic conditions.

Results

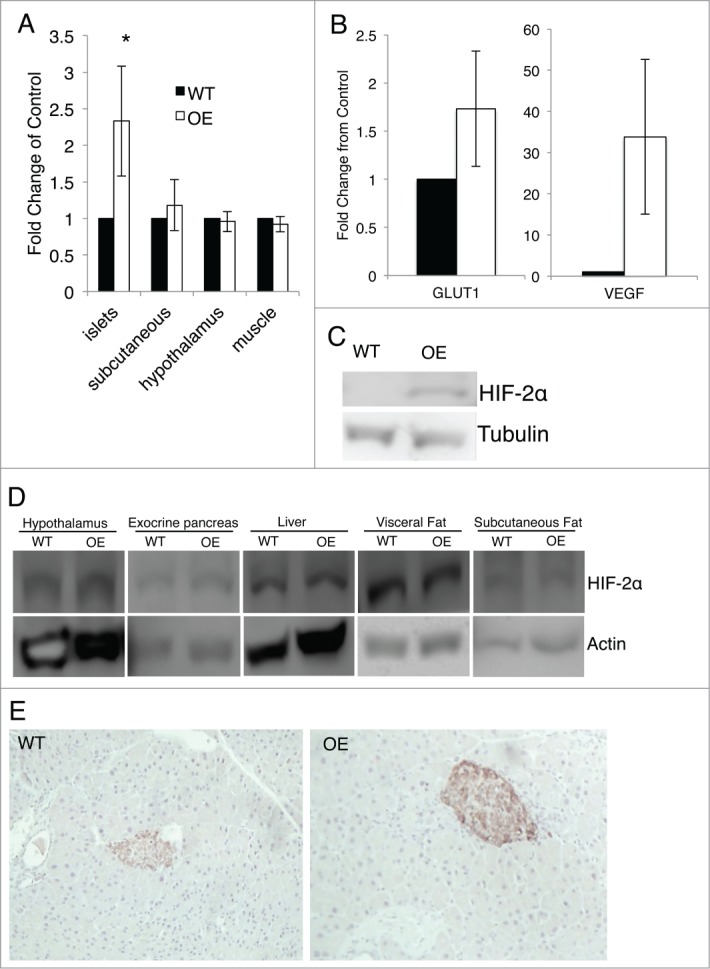

Generation of the Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice

To investigate the role for HIF-2α in islet biology, we generated mice that overexpressed HIF-2α specifically in the pancreas. We isolated RNA and protein from islets to examine HIF-2α expression. We achieved an approximate 2.5 fold increase in HIF-2α gene expression as evidenced by quantitative RT-PCR in isolated islets of Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice compared to cre positive wild-type (WT) littermates (Fig. 1A). We confirmed activation of HIF-2α in our overexpression mice by measuring gene expression of HIF-2α target genes, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Our HIF-2α overexpression mice had increased VEGF and GLUT1 gene expression compared to WT littermates (Fig. 1B). Similarly, in isolated islets, we saw increased protein expression of HIF-2α in our OE mice compared to WT mice as shown by Western blot (Fig. 1C). We confirmed that HIF-2α overexpression was islet specific, as in other tissues including subcutaneous fat, hypothalamus and muscle, there was no difference in HIF-2α levels in the PDX1+HIF-2α OE compared to WT mice as determined by quantitative RT-PCR as well as Western blot (Fig. 1A and D). Finally, we immunostained pancreatic sections for HIF-2α and saw increases in HIF-2α in islets of HIF-2α OE mice compared to WT littermate controls (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Overexpression of HIF-2α in the pancreas. (A) HIF-2α transcript levels were measured by quantitative PCR in isolated islets, subcutaneous fat, muscle and hypothalamus. Measurements were normalized to GAPDH (n = 3 for each genotype). (B) VEGF and GLUT1 gene expression in isolated islets was measured by quantitative PCR. Measurements were normalized to 18S (n = 3 for each genotype). (C) HIF-2α protein levels were measured by Western blot in islets. (D) Protein levels of HIF-2α were measured by Western blot in hypothalamus, exocrine pancreas, liver, visceral fat and subcutaneous fat. (E) HIF-2α expression in pancreatic sections were examined by immunohistochemistry. Significant differences are indicated as * (P < 0.05) and n = 3 for each genotype.

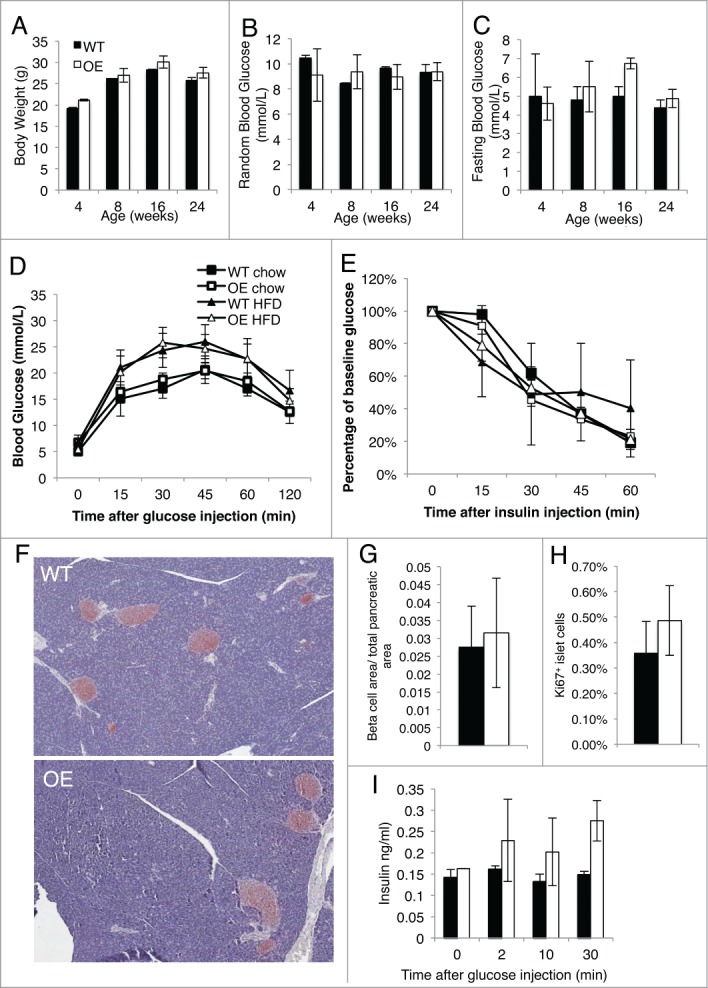

Glucose homeostasis is not altered with overexpression of HIF-2α under basal conditions on a chow diet

To assess the in vivo role of HIF-2α overexpression in the pancreas, we monitored our mice for changes in body weight and fed and fasting blood glucose levels at 4, 8, 16 or 24 weeks of age on chow diet. Our Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice and WT control littermates did not differ in any of these parameters (Fig. 2A–C). Next, we measured glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in our Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT littermates by i.p. glucose and insulin tolerance test, respectively. Our results did not show any significant differences in these measurements between our Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice at 16 (Fig. 2D and E) and 24 (Fig. 3D and E) weeks of age. Beta cell area was measured on insulin-immunostained pancreas sections of chow diet mice and this was also not different in Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice compared to WT littermates (Fig. 2F and G). Since HIF-2α has been shown to function in key processes such as proliferation and apoptosis, we examined β cell proliferation by measuring Ki67 expression in islets and found no significant differences in proliferation in our mice fed a chow diet at 16 weeks of age (Fig. 2H) or at 24 weeks of age (Fig 3G). In vivo insulin secretion was examined following glucose challenge to measure β cell function, and HIF-2α overexpression did not alter glucose-stimulated insulin secretion compared to WT at 16 weeks of age (Fig 2I) nor at 24 weeks of age (Fig 3H). These results show that HIF-2α overexpression in β cells does not alter β cell mass or function at 16 or 24 weeks of age on a chow diet.

Figure 2.

HIF-2α overexpression does not alter glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity or β cell area at 4 months of age. (A) Mice were monitored from birth up to 24 weeks of age and body weight of the WT and Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice was recorded. (B and C) Fed (B) and fasting (C) blood glucose in male Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and Pdx1+HIF-2α WT mice were measured from birth to 24 weeks of age. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM and n = 4–6 per genotype. (D) Glucose tolerance tests were performed on Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice aged 16 weeks of age on chow diet or after 8 weeks of HFD. E) Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice on chow diet or after 8 weeks HFD were subjected to insulin tolerance test by i.p. injection of insulin at 16 weeks of age. (F) Representative image, x20 of isolated pancreas sections immunostained for insulin in Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice on a chow diet at 16 weeks of age. (G) Beta cell area per total pancreatic area was determined on insulin-immunostained pancreatic sections in Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice at 16 weeks of age on chow diet. (H) Pancreas sections were immunostained for Ki67. Approximately 1000-2000 islet cells per animal were examined. (I) In vivo insulin secretion following i.p. glucose injection in chow diet fed mice at 16 weeks of age. For all experiments n = 3–8 for each genotype and the data is presented as the mean ± SEM.

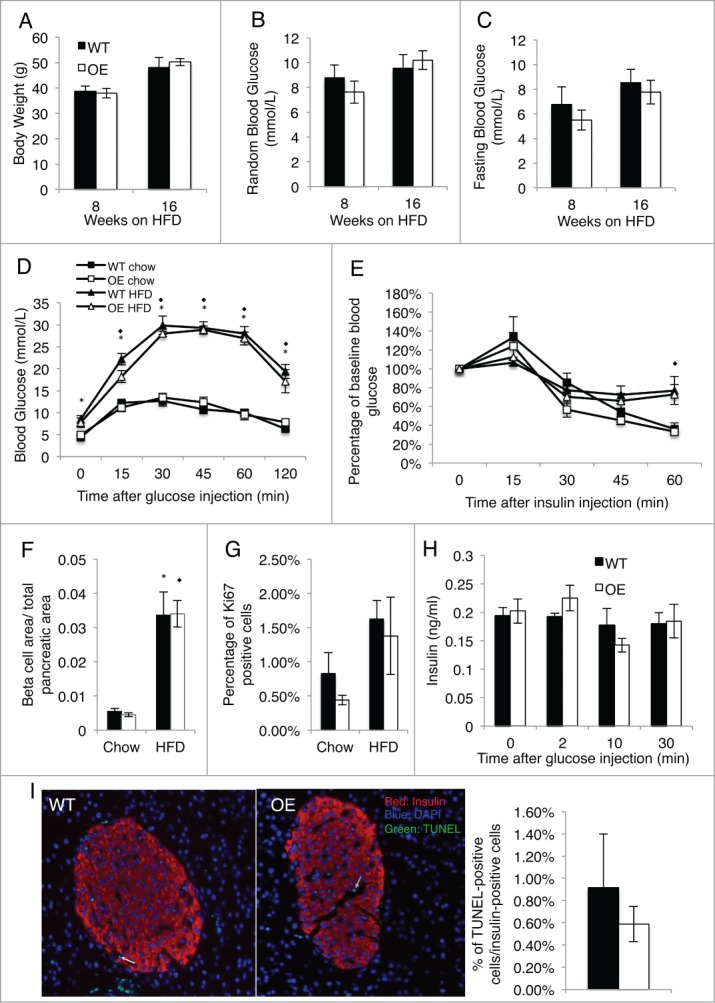

Figure 3.

Overexpression of HIF-2α in β cells does not alter glucose homeostasis after prolonged high fat diet. Mice were placed on a high fat diet (HFD) at 8 weeks of age. (A) Body weight of Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT littermates after 8 and 16 weeks HFD feeding. (B) Random blood glucose of Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice after 8 and 16 weeks of HFD. (C) Fasting blood glucose of HIF-2α OE and WT mice after 8 and 16 weeks of HFD. (D) Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice underwent glucose tolerance tests by i.p. injection at 24 weeks of age on chow diet or following 16 weeks of HFD. (E) Insulin tolerance tests were performed on Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice following feeding of a HFD 16 weeks of HFD or on chow diet at 24 weeks of age. (F) Insulin-immunostained pancreatic sections were used to determine β cell area per total pancreatic area in Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice at 24 weeks of age on chow diet or after 16 weeks of HFD. (G) Ki67 immunostained pancreas sections in chow diet and HFD fed mice. Approximately 1000–2000 islet cells per animal were analyzed. (H) In vivo glucose stimulated insulin secretion in 24 week old chow fed mice. (I) Representative images of pancreatic sections and quantification of Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice after 16 weeks of HFD stained for TUNEL. Approximately 1000 islet cells per animal were counted. For all experiments n = 5–6 per genotype and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences (P < 0.05) represent changes between chow diet and HFD and are indicated as * (WT) or ⋄ (OE).

Pancreas specific overexpression of HIF-2α does not alter glucose homeostasis after a high fat diet

To assess whether HIF-2α overexpression in islets had any effect upon metabolic challenge, we placed our Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice and WT littermates on a HFD starting at 8 weeks of age for a 16-week duration. With HFD feeding, both Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT mice had increased body weight compared to chow diet and developed progressive insulin resistance and glucose intolerance compared to chow diet mice. However, there were no significant differences in body weight or fed or fasting blood glucose between the Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 3A–C); nor in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity as measured by GTT and ITT between the 2 genotypes after HFD feeding (Fig. 3D and E). With prolonged HFD we saw increased β cell area (Fig. 3F) and increased β cell proliferation as determined by Ki67 staining (Fig. 3G) in comparison to age matched chow diet mice. However, there was no significant difference in either of these measures between Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice and their WT littermates. Finally, following prolonged HFD, there were no significant differences in apoptosis between Pdx1+HIF-2α OE mice and WT controls as determined by transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) (Fig. 3I). Given the number of mice used in this study a large difference in β cell proliferation and apoptosis is unlikely. Overall, our results show that HIF-2α overexpression in the pancreas does not result in significant differences in glucose homeostasis following HFD or under basal conditions.

Discussion

Pancreatic β cell function is critical for normal glucose homeostasis. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are characterized by insufficient functional β cell mass. The HIF pathway is most widely recognized for its role in cellular adaptation and survival in conditions of hypoxia. Activation of the HIF pathway results in the stabilization of HIF-α subunits, formation of the active heterodimer and upregulation of several target genes that play a role in numerous cellular processes such as apoptosis, angiogenesis and proliferation. Previously, both the activation and inhibition of the HIF pathway in β cells have been shown to alter glucose tolerance and insulin secretion. HIF-2α is one of the oxygen dependent HIF-α subunits and activation of HIF-2α results in the upregulation of numerous genes such as vascular endothelial growth factor, glucose transporter 1 and erythropoietin.

HIF-2α deficiency in mice resulted in early lethality at various stages as shown by different groups. In one study, loss of HIF-2α caused embryonic lethality between E12.5 and E16.5 due to impaired catecholamine production.26 Another study showed that loss of HIF-2α caused defects in blood vessel formation and resulted in embryonic lethality between E9.5 and E12.5.27 A different group showed that HIF-2α deficient mice died within hours post-natally due to abnormal lung maturation.28 These variations in phenotypes were attributed to the differences in the genetic background used by the multiple groups. HIF-2α has also been shown to be essential for normal pancreatic development.29 During pancreas development, HIF-2α is expressed in developing endothelial cells as well as endocrine progenitor cells. In HIF-2α null embryos, endocrine differentiation was impaired with a greater tendency toward α cell fate.29 Post-natally however, HIF-2α expression was only detectable in clusters of endocrine cells.29 While HIF-2α is shown to be essential for normal endocrine development in the pancreas, it was not clear whether this was due to direct effects of HIF-2α in endocrine islet cells. To this end, in the present study we examined the in vivo role of HIF-2α overexpression specifically in pancreatic islets and its effect in β cell mass and function. We show that specific excess of HIF-2α in the pancreas does not alter normal endocrine development in the pancreas.

Our results show no differences in fed or fasting blood glucose, glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity in the Pdx1+HIF2α OE mice compared to WT littermates under basal conditions on a chow diet. While our HFD-fed mice developed insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, mice that overexpress HIF-2α in the pancreas did not show differences in random or fasting blood glucose nor did it reveal any differences in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity compared to WT littermates after 16 weeks of HFD. Interestingly, HIF-2α haplodeficiency in mice on a normal chow diet also did not report any differences in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity.25 These findings are consistent with our study in the HIF-2α OE mice on chow diet. However, upon HFD feeding, HIF-2α heterozygous-null mice exhibited more aggravated glucose intolerance and insulin resistance compared to WT mice.25 Thus one might have expected that excess HIF-2α would protect mice from glucose intolerance and insulin resistance after HFD. However, with specific overexpression of HIF-2α in the pancreatic β cells, we did not see any significant differences in either of these measures following HFD. Although we saw no differences, our study only examined overexpression in the pancreas, whereas the study by Choe et al25 examined the effects of whole body HIF-2α haplodeficiency, which could result from influences of multiple organs. These HIF-2α haplodeficient mice showed increased expression of proinflammatory genes and M1 macrophages in adipose tissue.25 Previous studies have also shown a role for HIF-2α in glucose sensing in the hypothalamus23 as well as insulin signaling in hepatocytes.24 Together these findings show that while HIF-2α may play an essential role in some metabolic tissues, its overexpression in the pancreas alone is not sufficient to alter normal glucose homeostasis.

Previous studies found that HIF-2α plays important roles in proliferation and apoptosis. In renal clear cell carcinoma cells overexpression of HIF-2α promoted proliferation whereas there was a decrease in proliferation with inhibition of HIF-2α.2 Additionally, HIF-2α was shown to promote proliferation in primary mouse embryo fibroblasts as well as NIH3T3 cells,2 and in human haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, HIF-2α was shown to promote survival.4 We, on the other hand, saw no significant differences in β cell proliferation in HIF-2α OE mice after both chow and HFD compared to WT littermate controls. In addition, our HFD fed mice had no detectable differences in apoptosis between HIF-2α OE and WT littermates as assessed by TUNEL following prolonged HFD. These findings suggest that an excess of HIF-2α in the pancreas does not significantly change β cell proliferation or apoptosis thus leading to no differences in β cell mass.

In summary, our study was the first to examine the overexpression of HIF-2α in β cells and we revealed no differences between Pdx1+HIF-2α OE and WT littermates in body weight, random or fasting blood glucose. Additionally, no significant differences in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity after glucose tolerance test or insulin tolerance test during both basal conditions on a chow diet or during metabolic challenge after high fat diet feeding were detected. Finally, we saw no difference in β cell function, proliferation and apoptosis. These findings suggest that the HIF pathway is a complex pathway and that activation of HIF-2α in the pancreas does not play a significant role in glucose homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Protocol

HIF-2α overexpression in the pancreatic islets (Pdx1+HIF-2α OE) was achieved by Cre-mediated excision of a stop codon driven by the Pdx1 promoter in a mutant mouse model expressing a HIF-2α variant with mutated proline residues in order to prevent degradation by VHL.30 Cre positive wild-type (WT) littermates were used as controls. PCR of tail DNA was used to determine genotypes for Cre and HIF-2α. For all experiments male mice were used and animals were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle with free access to water and standard irradiated rodent chow (5% fat, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, USA). A cohort of mice was fed a HFD (60% fat, 24% carbohydrates and 16% protein based on caloric content; F3282; Bio-Serv, French Town, USA) starting at 8 weeks of age for 16 weeks. All protocols were approved by the Toronto General Research Institute Animal Care Committee.

Metabolic studies

Glucose tolerance tests were performed by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of glucose at a dose of 1g per kg of body weight on overnight (14–16 hours) fasted mice. Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 120 min after glucose injection. Insulin tolerance tests were performed on mice fasted for 4 h using by i.p. injection using human recombinant insulin (NovolinR; Novo Nordisk, Toronto, Ontario) at a dose of 0.75 unit per kg of body weight for chow diet mice and 1.5 unit per kg of body weight for HFD-fed mice and blood glucose was measured at 0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes after the injection of insulin. Mice were fasted for 14-16 hours prior to measurements of glucose stimulated insulin secretion. Glucose was given by i.p. injection at a dose of 3 g per kg of body weight and tail venous blood was collected at 0, 2, 10 and 30 minutes following glucose injection. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL) kit using a rat insulin standard was utilized to measure insulin levels.

Immunohistochemistry

Pancreas tissue was isolated and fixed for 24 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PBS (pH 7.4). For each sample, at least 3 levels of pancreas sections were obtained at 150 μM intervals and were immunostained for insulin, Ki67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) or HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals, Colorado, USA). Insulin slides were scanned by ScanScope ImageScope System at x20 magnification and analyzed using ImageScope version 9.0.19.1516 software (Aperio Technologies, Vista, USA) for β cell area which was measured over total pancreatic area.

Transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling assay

The transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Roche Biochemicals, Bazel, Switzerland) was used to examine β cell apoptosis according the manufacturer's protocol. Slides were imaged by a Zeiss inverted fluorescent microscope (Advanced Optical Microscopy Facility, Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

Quantitative PCR

RNA from whole islets was isolated using the RNeasy mini plus RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Germantown, USA) using the protocol provided by the manufacturer. RNA from hypothalamus, muscle and subcutaneous fat tissues was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed with random primers using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase enzyme (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, USA) and using a 7900HT Fast-Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, USA). The primer sequence for HIF-2α is available upon request. Samples were run in triplicate.

Western blotting

Protein lysates of isolated islets, muscle, subcutaneous fat, visceral fat, liver and exocrine pancreas were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies for HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals, Colorado, USA). Western blots were quantified with Image J software.

Statistical analysis

All data is presented as the mean ± SEM. Analysis was performed on the data by a two-tailed, independent Student t test or a one-way ANOVA, as appropriate. Statistically significant values were determined by p values <0.05.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Andras Nagy (Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) for generously providing the HIF-2α mice.

Funding

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR MOP-81148). MW is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Signal Transduction in Diabetes Pathogenesis. JJB was supported by a Banting and Best Diabetes Centre Novo-Nordisk Studentship. SYS is supported by a CIHR Doctoral Award, a Doctoral Student Research Award from the Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) and a Canadian Liver Foundation Graduate Studentship. TS is supported by Doctoral Awards from the CIHR and the CDA and by the Banting and Best Diabetes Centre Novo-Nordisk Studentship. EPC is supported by a Doctoral Award from the CDA.

References

- 1. Wenger RH, Gassman M. Oxygen(es) and the hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Biol Chem 1997; 378:609-16; PMID:9278140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, Diehl JA, Simon MC. HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell 2007;11:335-47; PMID:17418410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bertout JA, Majmundar AJ, Gordan JD, Lam JC, Ditsworth D, Keith B, Brown EJ, Nathanson KL, Simon MC. HIF2α inhibition promotes p53 pathway activity, tumor cell death, and radiation responses. PNAS 2009; 106:14391-96; PMID:19706526; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0907357106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rouault-Pierre K, Lopez-Onieva L, Foster K, Anjos-Afonso F, Lamrissi-Garcia I, Serrano-Sanchez M, Mitter R, Ivanocix Z, de Verneuil H, Gribben J, et al. HIF-2 α protects human hematopoietic stem/progenitors and acute myeloid leukemic cells from apoptosis induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Stem Cell 2013; 13:549-63; PMID:24095676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 1995; 270:1230-1237; PMID:7836384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang GL, Jian BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. PNAS 1995; 92:5510-14; PMID:7539918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cockman ME, Masson N, Mole DR, Jaakkola P, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Maher ER, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:25733-41; PMID:10823831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Rourke JF, Tian YM, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW. Oxygen-regulated and transactivating domains in endothelial PAS protein 1: comparison with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:2060-71; PMID:9890965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiesener MS, Turley H, Allen WE, Willam C, Eckardt KU, Talks KL, Wood SM, Gatter KC, Harris AL, Pugh CW, et al. Induction of endothelial PAS domain protein-1 by hypoxia: characterization and comparison with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Blood 1998; 92:2260-68; PMID:9746763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gunton JE, Kulkarn RN, Yim S, Okada T, Hawthorne WJ, Tseng YH, Roberson RS, Ricordi C, O’Connell PJ, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Loss of ARNT/HIF1beta mediates altered gene expression and pancreatic-islet dysfunction in human type 2 diabetes. Cell 2005; 122:337-49; PMID:16096055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dror V, Kalynyak TB, Bychkivska Y, Frey MHZ, Tee M, Jeffrey KD, Nguyen V, Luciani DS, Johnson JD. Glucose and endoplasmic reticulum calcium channels regulate HIF-1β via presenilin in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283:9909-16; PMID:18174159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng K, Ho K, Stokes R, Scott C, Lau SM, Hawthorne WJ, O’Connell PJ, Loudovaris T, Kay TW, Kulkarni RN, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha regulated beta cell function in mouse and human islets. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:2171-83; PMID:20440072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zehetner J, Danzer C, Collins S, Eckhardt K, Gerber PA, Ballschmieter P, Galvanovskis J, Shimomura K, Ashcroft FM, Thorens B, et al. PVHL is a regulator of glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. Genes Dev 2008; 33:3135-46; PMID: 19056893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.496908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cantley J, Selman C, Shukla D, Abramov AY, Forstreuter F, Esteban MA, Claret M, Lingard SJ, Clements M, Harten SK, et al. Deletion of the von Hippel-Lindau gene in pancreatic beta cells impairs glucose homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:125-35; PMID:19065050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Puri S, Cano DA, Hebrok M. A role for von Hippel-Lindau protein in pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes 2009; 58:433-41; PMID:19033400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi D, Cai EP, Schroer SA, Wang L, Woo M. Vhl is required for normal pancreatic B cell function and the maintenance of B cell mass with age in mice. Lab Invest 2011; 91:527-38; PMID:21242957; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/labinvest.2010.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. PNAS 1997; 94:4273-78; PMID:9113979; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flamme I, Frohlich T, von Reutern M, Kappel A, Damert A, Risau W. HRF, a putative basic helix-loop-helix-PAS-domain transcription factor is closely related to hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and developmentally expressed in blood vessels. Mech Dev 1997; 63:51-60; PMID:9178256; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0925-4773(97)00674-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. H ogenesch JB, Chan WK, Jackiw VH, Brown RC, Gu Y, Pray-Grant M, Perdew GH, Bradfield CA. Characterization of a subset of the basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS superfamily that interacts with components of the dioxin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:8581-93; PMID:9079689; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wiesener MS, Jurgensen JS, Rosenberger C, Scholze CK, Horstrup JH, Warnecke C, Mandriota S, Bechmann I, Frei UA, Puch CQ, et al. Widespread hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2alpha in distinct cell populations of different organs. FASEB J 2003; 17:271-73; PMID:12490539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenberger C, Mandriota S, Jurgensen JS, Wiesener MS, Horstrup JH, Frei U, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and -2alpha in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:1721-32; PMID:12089367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.ASN.0000017223.49823.2A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cantley J, Grey ST, Maxwell PH, Withers DJ. The hypoxia response pathway and β-cell function. Diabetes, Obes Metab 2010; 12:159-67; PMID:21029313; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang H, Zhang G, Gonzalez FJ, Park SM, Cai D. Hypoxia-inducible factor directs POMC gene to mediate hypothalamic glucose sensing and energy balance regulation. PLoS Biology 2011; 9 e1001112; PMID:21814490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wei K, Piecewiz S, McGinnis L, Taniguchi C, Wiegand S, Anderson K, Chan C, Mulligan K, Kuo D, Yuan J, et al. A liver HIF-2 α-Irs2 pathway sensitizes hepatic insulin signaling and is modulated by Vegf inhibition. Nat Med 2013; 19:1331-37; PMID:24037094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choe SS, Shin KC, Ka S, Chun JS, Kim JB. Macrophage HIF-2α ameliorates adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Diabetes 2014; 63:3359-71; PMID:24947359; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tian H, Hammer RE, Matsumoto AM, Russell DW, McKnight SL. The hypoxia-responsive transcription factor EPAS1 is essential for catecholamine homeostasis and protection against heart failure during embryonic development. Genes Dev 1998; 12:3320-24; PMID:9808618; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.12.21.3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peng J, Zhang L, Drysdale L, Fong GH. The transcription factor EPAS-1/hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha plays an important role in vascular remodeling. PNAS 2000; 97:8386-91; PMID:10880563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.140087397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. C ompernolle V, Brusselmans K, Acker T, Hoet P, Tjwa M, Beck H, Plaisance S, Dor Y, Keshet E, Lupu F, et al. Loss of HIF-2alpha and inhibition of VEGF impair fetal lung maturation, whereas treatment with VEGF prevents fatal respiratory distress in premature mice. Nat Med 2002; 8:702-10; PMID:12053176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen H, Houshmand G, Mishra S, Fong G, Gittes GK, Esni F. Impaired pancreatic development in Hif2-alpha deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 399:440-45; PMID:20678473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim WY, Safran M Buckley MRM, Ebert BL, Glickman J, Bosenberg M, Regan M, Kaelin WG, Jr. Failure to prolyl hydroylate hypoxia-inducle factor α phenocopies VHL inactivation in vivo. EMBO J 2006; 25:4650-62; PMID:16977322; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]