Abstract

Background

We previously discovered that high copeptin is associated with incidence of diabetes mellitus (diabetes), abdominal obesity, and albuminuria. Furthermore, copeptin predicts cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction in diabetic patients, but whether it is associated with heart disease and death in individuals without diabetes and prevalent cardiovascular disease is unknown. In this study, we aim to test whether plasma copeptin (copeptin), the C-terminal fragment of arginine vasopressin prohormone, predicts heart disease and death differentially in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals.

Methods

We related plasma copeptin to a combined end point composed of coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), and death in diabetes (n = 895) and nondiabetes (n = 4187) individuals of the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study–Cardiovascular cohort.

Results

Copeptin significantly interacted with diabetes regarding the combined end point (P = .006). In diabetic individuals, copeptin predicted the combined end point (hazard ratio [HR] 1.32 per SD, 95% CI 1.10-1.58, P = .003) after adjustment for conventional risk factors, prevalent HF and CAD, and remained significant after additional adjustment for either fasting glucose (P = .02) or hemoglobin A1c (P = .02). Furthermore, in diabetic individuals, copeptin predicted CAD (HR 1.33 per SD, 95% CI 1.04-1.69, P = .02), HF (HR 1.62 per SD, 95% CI 1.09-2.41, P = .02), and death (HR 1.32 per SD, 95% CI 1.04-1.68, P = .02). Interestingly, among nondiabetic individuals, copeptin was not associated with any of the end points.

Conclusions

Copeptin predicted heart disease and death, specifically in diabetes patients, suggesting copeptin and the vasopressin system as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target for diabetic heart disease and death.

Introduction

Vasopressin (AVP), also called antidiuretic hormone, is a peptide involved in diverse physiological functions and released from the posterior pituitary gland in conditions of decreased blood volume or high plasma osmolality. Vasopressin exerts its antidiuretic effects through the AVP 2 receptor in the kidney.1 The AVP 1a receptor is involved in blood platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction in the vessels and gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in the liver,2–5 whereas the AVP 1b receptor is found in the anterior hypophysis and the Langerhans islets of the pancreas, where it mediate secretion of adrenocorticotrophic hormone, insulin, and glucagon.6,7 Thus, AVP may affect glucose metabolism through several different mechanisms.

Vasopressin is a small, short-lived peptide, and most assays measuring AVP have relatively limited sensitivity. An assay has been developed to measure plasma copeptin (copeptin), the C-terminal portion of the AVP precursor. Copeptin is considered to be a stable, reliable, and clinically useful surrogate marker for AVP.8 In the Swedish population-based Malmö Diet and Cancer study Cardiovascular Cohort (MDC-CC), we recently found elevated copeptin to be associated with incident diabetes mellitus (diabetes) independently of a range of different clinically used diabetes risk factors including plasma glucose and insulin,9,10 as well as independently associated with incident abdominal obesity.10 Furthermore, copeptin is proposed as a useful biomarker in cardiovascular and renal disease,11 and is suggested to contribute to the progression and predict prognosis in heart failure (HF)12,13 and to predict prognosis in stroke14,15 and myocardial infarction.16 In the acute setting, copeptin can rule out myocardial infarction.17–19 In addition, elevated copeptin has previously been associated with cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction in diabetes patients,20 and with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients with diabetes.21 However, it is not known whether copeptin predicts heart disease or death in unselected diabetic and nondiabetic individuals in the population. Based on our previous findings that copeptin predicts diabetes,9,10 and its predictive role in diabetes patients with hemodialysis21 and myocardial infarction,20 we hypothesized that elevated copeptin predicts coronary artery disease (CAD), HF, and death differentially in individuals with diabetes and individuals without diabetes.

Methods

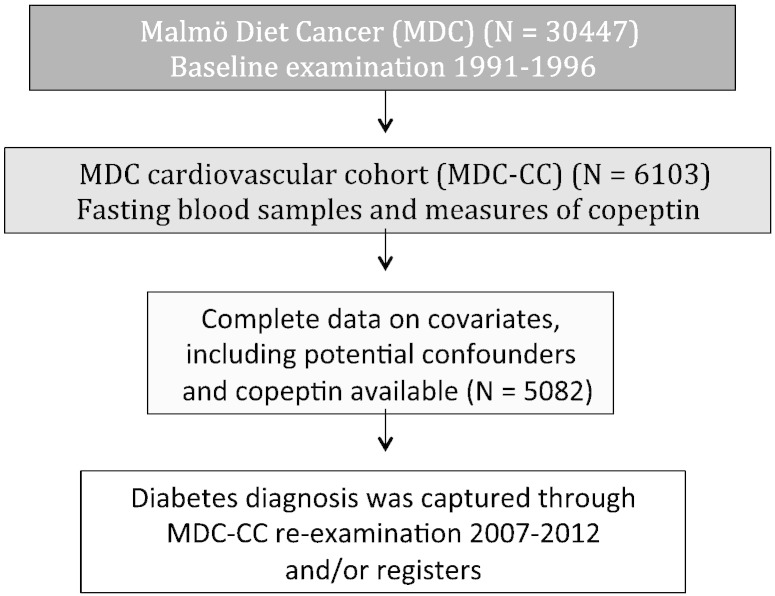

The MDC is a population-based prospective cohort consisting of 30,447 individuals born between 1923 and 1950 and surveyed at a baseline examination in 1991 to 1996.22 The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Lund University. All participants provided written informed consent. From the MDC cohort, 6,103 subjects were randomly selected to be studied for the epidemiology of carotid artery disease. This sample is referred to as the MDC-CC and was examined in 1991 to 1994.23 At the MDC-CC baseline investigation, fasting plasma samples were available in 5,405 individuals and copeptin was measured. Complete data on covariates, including potential confounders and copeptin, were available in 5,082 individuals (Figure 1). Blood pressure was measured using a mercury-column sphygmomanometer after 10 minutes of rest in the supine position. Data on current smoking and use of antihypertensive treatment were ascertained from a baseline questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Population description.

Furthermore, the MDC-CC was reexamined between 2007 and 2012 (67% participation rate) (Figure 1) with fasting plasma samples and additional measurement of an oral glucose tolerance test.10

Ascertainment of diabetes diagnosis

Diabetes cases were defined based on 6 different national and regional diabetes registers as detailed in online Supplementary Appendix. In addition, diabetes cases at the baseline examination of MDC-CC were obtained by self-report of a physician diagnosis or use of diabetes medication according to a baseline questionnaire, or fasting whole blood glucose of ≥6.1 mmol/L (corresponding to fasting plasma glucose concentration of ≥7.0 mmol/L). Furthermore, a diabetes diagnosis could be captured at the MDC-CC reinvestigation by self-report of a physician diagnosis or use of diabetes medication according to a questionnaire or fasting plasma glucose of ≥7.0 mmol/L or a 120-minute value post–oral glucose tolerance test plasma glucose >11.0 mmol/L.

Participants were classified as diabetic individuals regardless of whether diabetes was established before or at the baseline examination or during a follow-up period of 15.6 ± 2.8 years after the baseline examination. In subanalyses, diabetes cases were divided into those who had diabetes before or at the baseline examination (prevalent diabetes) (Table III) and those who developed diabetes during follow-up (incident diabetes) (Table IV).

Table III.

ZLnCopeptin in prediction of combined end point and its components in individuals with prevalent diabetes

| n total/n event | HR (95% CI) | P⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point (CAD + death + HF)† | 435/185 | 1.21 (0.97-1.52) | .10 |

| CAD‡ | 435/100 | 1.11 (0.84-1.49) | .47 |

| HF§ | 435/38 | 1.74 (1.02-2.98) | .04 |

| Death† | 435/38 | 1.28 (0.96-1.70) | .09 |

HRs are expressed as per SD increment of ln-transformed copeptin.

Adjusted for age, sex, LDL, HDL, systolic BP, antihypertensive treatment, and smoking (model 1).

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD and prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

Table IV.

ZLnCopeptin in prediction of combined end point and its components in individuals with incident diabetes

| n total/n event | HR (95% CI) | P⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point (CAD + death + HF)† | 460/102 | 1.48 (1.09-2.02) | .01 |

| CAD‡ | 460/64 | 1.76 (1.17-2.65) | .007 |

| HF§ | 460/20 | 1.43 (0.71-2.89) | .32 |

| Death† | 460/42 | 1.30 (0.82-2.08) | .27 |

HRs are expressed as per SD increment of ln-transformed copeptin.

Adjusted for age, sex, LDL, HDL, systolic BP, antihypertensive treatment, and smoking (model 1).

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD and prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

Ascertainment of end points

Cases of CAD, HF, and death were identified by the Swedish National Patient Register, which is a principal source of data for numerous research projects and covers more than 99% of all somatic and psychiatric hospital discharges and Swedish Hospital-based outpatient care24; the Swedish Cause-of-Death Register, which comprises all deaths among Swedish residents occurring in Sweden or abroad25,26; and the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR).27 The registers have previously been validated for classification of outcomes for HF28 and myocardial infarction.24,29,30 Coronary artery disease was defined as fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, death due to ischemic heart disease, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting, whichever came first, on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions codes 410 and I21, respectively, in the Swedish National Patient Register or the Swedish Cause-of-Death Register, codes 412 and 414 (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision) or I22, I23, and I25 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision) of the Swedish Cause-of-Death Register. Coronary artery bypass grafting was identified from national classification of surgical procedures, KKÅ from 1963 until 1989 and Op6 since then. Coronary artery bypass grafting was defined as a procedure code of 3065, 3066, 3068, 3080, 3092, 3105, 3127, 3158 (Op6), or FN (KKÅ97). Percutaneous coronary intervention was defined based on the operation codes FNG05 and FNG02.

Laboratory measurements

Analyses of fasting plasma lipids, insulin, and whole blood glucose at the time of baseline examination, as well as fasting plasma glucose at time of follow-up, were performed at the Department of Clinical Chemistry, Skane University Hospital in Malmö, which is attached to a national standardization and quality control system. Copeptin was measured at baseline in MDC-CC in fasting plasma samples stored at −80°C using a commercially available chemiluminescence sandwich immunoassay with coated tubes (B.R.A.H.M.S. AG, Hennigsdorf, Germany).8 The assay used 2 polyclonal antibodies to the amino acid sequences 132 to 164 of preprovasopressin in the C-terminal region of the precursor. One antibody was bound to polystyrene tubes, and the other was labeled with chemiluminescent acridinium ester for detection. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was determined using the Dimension RxL N-BNP (Dade-Behring, Germany).31 Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured at the Department of Clinical Chemistry, Skane University Hospital in Malmö, using the Swedish Mono-S standardization system. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease glomerular filtration rate formulae (mL/min per 1.73 m2) = 175 • (P-creatinine/88.4)−1.154 • age−0.203 (•0.742 if female; •1.210 if black).32 Adjustment for race was not applicable in this cohort of white participants.

Statistics

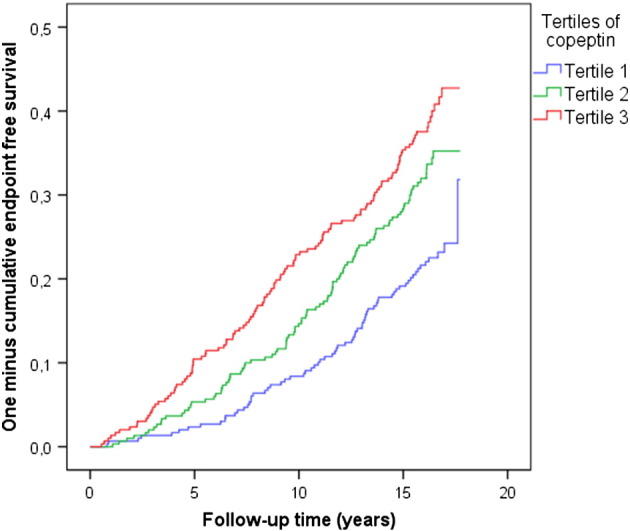

SPSS statistical software (version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all calculations. Copeptin, insulin, and glucose were not normally distributed and were transformed using the natural logarithm. A combined variable of prevalent and incident diabetes was used. An interaction term (diabetic status × copeptin) was used to ascertain a link between copeptin and heart disease and death among diabetic individuals. The interaction test was conducted by entering the interaction term into a multivariate logistic regression together with diabetes status and copeptin, and with the combined end points as the outcome variable. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess association between copeptin and disease among nondiabetic and diabetic cases, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to describe the rate of primary end point over time in tertiles of baseline copeptin levels (Figure 2). A 2-sided P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for primary end point (CAD, HF, or death) according to tertiles of baseline copeptin levels in diabetic individuals.

Sources of funding

Drs Enhörning and Melander were supported by grants from the European Research Council (StG-282255), Swedish Medical Research Council, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, the Medical Faculty of Lund University, Malmö University Hospital, the Albert Påhlsson Research Foundation, the Crafoord Foundation, the Ernhold Lundströms Research Foundation, the Region Skane, the Hulda and Conrad Mossfelt Foundation, the King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria Foundation, the Lennart Hanssons Memorial Fund, the Wallenberg Foundation, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. We also thank B.R.A.H.M.S. and Dade-Behring for their support of assay measurements.

The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all analyses, the drafting and editing of the manuscript, and its final contents.

Results

There was a significant interaction between diabetes and copeptin (diabetes × copeptin) regarding the primary end point (CAD, HF, or death; P = .006). Thus, we stratified our population into nondiabetic and diabetic individuals (Table I). Of the 895 individuals with diabetes, 287 had primary end point, 164 had a first CAD event, 58 had a first HF event, and 165 died during a mean follow-up time of 14.4 ± 4.0 years. Among diabetic individuals, after adjustment for conventional risk factors (age, sex, low-density lipoprotein [LDL], high-density lipoprotein [HDL], systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive treatment, smoking), copeptin predicted the primary end point as well as its individual components (Table II). Cumulative incident rates among diabetic individuals in different tertiles of baseline copeptin levels are shown in a Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the primary end point (Figure 2). In individuals without diabetes, copeptin was associated neither with the primary end point nor with any of its components (Table II).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics

| Diabetes cases (n = 895) | Nondiabetes cases (n = 4187) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (% men) | 51.4 | 38.4 |

| Age (y) | 58.5 ± 5.7 | 57.3 ± 6.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.0 ± 4.7 | 25.2 ± 3.6 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 148 ± 19 | 140 ± 19 |

| Antihypertensive treatment, n (%) | 268 (29.9) | 579 (13.8) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92.1 ± 14 | 81.9 ± 12 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 218 (24.4) | 1094 (26.1) |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.25 ± 0.34 | 1.42 ± 0.37 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 4.27 ± 1.03 | 4.15 ± 0.98 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 38 (4.2) | 65 (1.6) |

| History of HF, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) |

| Copeptin (pmol/L)⁎ | 6.46 (4.03-9.88) | 4.95 (3.05-7.82) |

| Insulin (mU/L)⁎ | 10.0 (7.0-15.0) | 6.0 (4.0-8.0) |

Values are presented as mean ± SD (if not otherwise specified).

Expressed as median (interquartile range).

Table II.

Copeptin in prediction of combined end point and its components in individuals with or without diabetes

| Diabetic cases |

Nondiabetic cases |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n total/n event | HR (95% CI) | P⁎ | P† | P‡ | P§ | n total/n event | HR (95% CI) | P⁎ | |

| Primary end point (CAD + death + HF)║ | 895/287 | 1.32 (1.10-1.58) | .003 | .02 | .02 | .002 | 4187/845 | 1.01 (0.95-1.09) | .70 |

| CAD ¶ | 895/164 | 1.33 (1.04-1.69) | .02 | .048 | .053 | .03 | 4187/319 | 1.02 (0.90-1.15) | .78 |

| HF# | 895/58 | 1.62 (1.09-2.41) | .02 | .04 | .04 | .02 | 4187/95 | 1.22 (0.94-1.58) | .13 |

| Death ║ | 895/165 | 1.32 (1.04-1.68) | .02 | .13 | .17 | .01 | 4187/599 | 1.00 (0.92-1.08) | .92 |

HRs are expressed as per SD increment of ln-transformed copeptin.

Adjusted for age, sex, LDL, HDL, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive treatment, and smoking (model 1).

Model adjusted for glucose on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for HbA1c on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for Insulin on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD and prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent CAD on top of model 1 adjustment.

Model adjusted for prevalent HF on top of model 1 adjustment.

After further adjustment for fasting whole blood glucose on top of conventional risk factors, copeptin remained significantly associated with the primary end point as well as with its components CAD and HF, whereas the association with death did not remain significant (Table II). Similarily, adjustment for HbA1c on top of conventional risk factors showed that the association between copeptin and the primary end point as well as its components CAD and HF remained significant or borderline significant, whereas the association between copeptin and death disappeared (Table II). Given our previous results showing a strong relationship between copeptin and hyperinsulinemia,9 we also additionally adjusted for fasting plasma insulin on top of conventional risk factors and found that the primary end point as well as its components CAD, HF, and death remained significantly associated with copeptin (Table II).

After adjustment for diabetes medication on top of conventional risk factors, copeptin still predicted the primary end point in diabetic individuals (hazard ratio [HR] 1.30 [1.08-1.55], P = .004).

Neither adjustment for CRP (HR 1.22 [1.02-1.46], P = .03) nor NT-proBNP (HR 1.28 [1.07-1.53], P = .008) on top of conventional risk factors changed the ability of copeptin to predict the primary end point in diabetic individuals.

Finally, to exclude the possibility that the relationship between copeptin and outcome was driven by differences in renal function, we adjusted for Modification of Diet in Renal Disease glomerular filtration rate on top of conventional risk factors in diabetic individuals and found that copeptin was independently associated with the primary outcome (P = .004), CAD (P = .02), HF (P = .02), and death (P = .03).

We then stratified our diabetic individuals into those who had diabetes before or at the baseline examination (prevalent diabetes) (Table III) and those who developed diabetes during follow-up (incident diabetes) (Table IV). Interestingly, the relationship between copeptin and the primary end point was stronger among incident diabetic individuals than among prevalent ones (Tables III and IV). Among incident diabetic patients, the primary end point and CAD were significantly related to copeptin, whereas among prevalent diabetic patients, only HF was significantly associated with copeptin (Tables III and IV).

There was no significant interaction between gender and copeptin on the primary end point neither among diabetic individuals nor among nondiabetic individuals, after adjustment for conventional risk factors.

Discussion

The key finding of the present study was that copeptin significantly interacted with diabetic status regarding the primary end point composed of CAD, HF, and death. Stratified analyses discovered that copeptin independently predicted the primary end point as well as its components CAD, HF, and death, specifically in diabetic individuals. We thus extend our previous findings that copeptin is an independent risk marker for diabetes development9,10 by showing that copeptin predicts the main fatal complications of diabetes.

Given the known association between copeptin and incident diabetes, as well as the cross-sectional relationship with glucose and insulin levels,9 the key question is whether our current findings are explained by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, or other detrimental effects linked to copeptin. That copeptin was related to the primary outcome independently of baseline levels of fasting glucose, HbA1c, and insulin level suggests that the copeptin-associated risk of heart disease and death is at least partially independent from glucotoxicity and insulin resistance.

Importantly, the actual onset of diabetes has been estimated to occur several years before clinical diagnosis33 and the exact duration of diabetes is therefore difficult to estimate. As duration of diabetes is a risk factor for its complications, we investigated whether the association between copeptin and outcome differed between prevalent and incident cases of diabetes. Although the number of events was generally low in these subgroups, we found that, if anything, the copeptin-related risk was stronger among incident cases of diabetes, suggesting that diabetes duration does not explain the link between copeptin and the primary end point. Furthermore, as the incident diabetes patients, by definition, acquire their diabetes status during follow-up, they have a shorter time at risk for the mortality component of the primary end point. If anything, we believe that these circumstances would bias our results toward the null.

Copeptin has previously been associated with microalbuminuria10,34 and kidney function decline in renal transplant recipients and polycystic kidney disease.35,36 In addition, elevated copeptin has been associated with cardiovascular events and death in hemodialysis patients with diabetes.21 Although the relationship between copeptin and outcome in our study was independent of renal function, it is possible that copeptin-mediated decline in renal function may explain the poor prognosis associated with high copeptin in diabetes individuals.

Natriuretic peptides, such as NT-proBNP, are established markers of HF. Their predictive and prognostic values in HF have been compared with copeptin in several studies.37–39 However, when adjusting for NT-proBNP on top of conventional risk factors in diabetic individuals, the ability of copeptin to predict the primary end point was not changed.

That we did not find any relationship between copeptin and the primary end point or with its components in the nondiabetic population is intriguing but in line with previous studies in which AVP was linked specifically to diabetic heart disease.20,21 In this study, it is unlikely to be a power issue because the nondiabetic sample and the number of end points within it was considerably greater than in the diabetic sample. Patients with diabetes have an increased risk of CAD and HF, and several hypotheses have been provided to explain the progression of heart disease in diabetes. Studies have shown disturbed endothelial function in the diabetic heart,40,41 and that blood coagulation in diabetic individuals is altered.42 Furthermore, elevated levels of von Willebrand factor is associated with increased cardiovascular risk in individuals with diabetes.43 It is possible that the AVP system, with its prothrombotic2 and vasoconstrictor3 effects as well as its von Willebrand factor release from endothelial cells,44 aggravates the diabetes-associated endothelial dysfunction and altered coagulation, and thus increases the risk of developing heart disease solely among diabetic patients.

As blood glucose-lowering therapy in high-risk type 2 diabetes patients has not been shown to effectively reduce cardiovascular or total mortality, but rather the opposite,45,46 it is essential to find pathophysiological links between diabetes development and its fatal complications. Whether the relationship between copeptin and both disease development and its fatal complications is causal or due to covariation with a thus far unknown factor is unknown. Assuming it is causal, lowering AVP, for example, by pharmacologic manipulation or extensive water intake, would represent a promising target for treatment of diabetes and its fatal complications.

Limitations

We study a Swedish population of whites, which is why this study is not generalizable to other ethnicities. Furthermore, it may be a limitation that our diabetic individuals are both prevalent and incident cases. Our diabetic individuals are derived from a population-based sample and could therefore be considered representative for diabetes individuals in the given age range. Given the high prevalence of heart disease among diabetic individuals, we did not exclude individuals with heart disease prior to the baseline examination, as this would result in a health selected nonrepresentative sample. However, as a result of this, there may be residual confounding. Instead, the analyses were adjusted for prevalent CAD and HF, respectively, and as the results remained significant after this adjustment, we believe that the risk associated with high copeptin is unlikely to be explained by prevalent heart disease. Neither did we exclude those subjects who got their incident heart disease diagnosis before their incident diabetes diagnosis, as we believe that this would also result in a nonrepresentative sample of incident diabetic patients. First, the actual onset of diabetes is known to occur several years before diagnosis,33 and second, a diagnosis of heart disease generally results in a major health screening in which it is likely to diagnose previously undiscovered diabetes.

We have previously shown that copeptin may be a promising marker for early identification of individuals with increased risk of diabetes.9 Our current data, showing a copeptin-related risk, which was stronger among incident cases of diabetes, suggest that copeptin may also be a good marker for detecting diabetes patients at a higher risk for developing severe complications and who might benefit from preventive therapy.

In conclusion, our results suggest that copeptin is a promising prognostic marker for diabetic heart disease and death. Furthermore, the pharmacologically modifiable AVP system47,48 may be a new therapeutic target in the prevention of secondary diseases and premature death among individuals with diabetes.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Appendix.

Individuals could be registered as having a diagnosis of diabetes in the nationwide Swedish National Diabetes Register,49 or the regional Diabetes 2000 register of the Scania region, of which Malmö is the largest city,50 or in the Swedish National Patient Register, which is a principal source of data for numerous research projects and covers more than 99% of all somatic and psychiatric hospital discharges and Swedish hospital-based outpatient care51; or they could be classified as diabetes cases if they had diabetes as a cause of death in the Swedish Cause-of-Death Register, which comprises all deaths among Swedish residents occurring in Sweden or abroad52,53; or if they had been prescribed antidiabetic medication as registered in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register54; or if they at least 2 HbA1c recordings ≥6.0% using the Swedish Mono-S standardization system (corresponding to 7.0% according to the US National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) in the Malmö HbA1c register, which analyzed and catalogued all HbA1c samples at the Department of Clinical Chemistry taken in institutional and noninstitutional care in the greater Malmö area from 1988 onward.

References

- 1.Lolait S.J., O'Carroll A.M., McBride O.W. Cloning and characterization of a vasopressin V2 receptor and possible link to nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nature. 1992;357:336–339. doi: 10.1038/357336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filep J., Rosenkranz B. Mechanism of vasopressin-induced platelet aggregation. Thromb Res. 1987;45:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohlstein E.H., Berkowitz B.A. Human vascular vasopressin receptors: analysis with selective vasopressin receptor antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;239:737–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitton P.D., Rodrigues L.M., Hems D.A. Stimulation by vasopressin, angiotensin and oxytocin of gluconeogenesis in hepatocyte suspensions. Biochem J. 1978;176:893–898. doi: 10.1042/bj1760893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keppens S., de Wulf H. The nature of the hepatic receptors involved in vasopressin-induced glycogenolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;588:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes C.L., Landry D.W., Granton J.T. Science review: Vasopressin and the cardiovascular system. Part 1—receptor physiology. Crit Care. 2003;7:427–434. doi: 10.1186/cc2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu-Basha E.A., Yibchok-Anun S., Hsu W.H. Glucose dependency of arginine vasopressin-induced insulin and glucagon release from the perfused rat pancreas. Metabolism. 2002;51:1184–1190. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgenthaler N.G., Struck J., Alonso C. Assay for the measurement of copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the precursor of vasopressin. Clin Chem. 2006;52:112–119. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.060038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enhorning S., Wang T.J., Nilsson P.M. Plasma copeptin and the risk of diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2010;121:2102–2108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.909663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enhorning S., Bankir L., Bouby N. Copeptin, a marker of vasopressin, in abdominal obesity, diabetes and microalbuminuria: the prospective Malmo Diet and Cancer Study cardiovascular cohort. Int J Obes. 2013;37:598–603. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgenthaler N.G. Copeptin: a biomarker of cardiovascular and renal function. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(Suppl. 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoiser B., Mortl D., Hulsmann M. Copeptin, a fragment of the vasopressin precursor, as a novel predictor of outcome in heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:771–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsmith S.R. Congestive heart failure: potential role of arginine vasopressin antagonists in the therapy of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urwyler S.A., Schuetz P., Fluri F. Prognostic value of copeptin: one-year outcome in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:1564–1567. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katan M., Fluri F., Morgenthaler N.G. Copeptin: a novel, independent prognostic marker in patients with ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:799–808. doi: 10.1002/ana.21783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan S.Q., Dhillon O.S., O'Brien R.J. C-terminal provasopressin (copeptin) as a novel and prognostic marker in acute myocardial infarction: Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide (LAMP) study. Circulation. 2007;115:2103–2110. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichlin T., Hochholzer W., Stelzig C. Incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller T., Tzikas S., Zeller T. Copeptin improves early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2096–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannitsis E., Kehayova T., Vafaie M. Combined testing of high-sensitivity troponin T and copeptin on presentation at prespecified cutoffs improves rapid rule-out of non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2011;57:1452–1455. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.161265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellbin L.G., Ryden L., Brismar K. Copeptin, IGFBP-1, and cardiovascular prognosis in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute myocardial infarction: a report from the DIGAMI 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1604–1606. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenske W., Wanner C., Allolio B. Copeptin levels associate with cardiovascular events in patients with ESRD and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:782–790. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010070691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berglund G., Elmstahl S., Janzon L. The Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. J Intern Med. 1993;233:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persson M., Hedblad B., Nelson J.J. Elevated Lp-PLA2 levels add prognostic information to the metabolic syndrome on incidence of cardiovascular events among middle-aged nondiabetic subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1411–1416. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson J.F., Andersson E., Ekbom A. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Board of Health and Welfare A finger on the pulse: Monitoring public health and social conditions in Sweden 1992-2002. Stockholm. 2003. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2003/2003-118-16 [27 Dec 2013]

- 26.Johansson L.A., Westerling R. Comparing Swedish hospital discharge records with death certificates: implications for mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarno G., Lagerqvist B., Carlsson J. Initial clinical experience with an everolimus eluting platinum chromium stent (Promus Element) in unselected patients from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingelsson E., Arnlov J., Sundstrom J. The validity of a diagnosis of heart failure in a hospital discharge register. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:787–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammar N., Alfredsson L., Rosen M. A national record linkage to study acute myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(Suppl. 1):S30–S34. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.suppl_1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindblad U., Rastam L., Ranstam J. Validity of register data on acute myocardial infarction and acute stroke: the Skaraborg Hypertension Project. Scand J Soc Med. 1993;21:3–9. doi: 10.1177/140349489302100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Serio F., Ruggieri V., Varraso L. Analytical evaluation of the Dade Behring Dimension RxL automated N-Terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) method and comparison with the Roche Elecsys 2010. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:1263–1273. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grubb A., Nyman U., Bjork J. Improved estimation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) by comparison of eGFRcystatin C and eGFRcreatinine. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. Feb 2012;72:73–77. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2011.634023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris M.I., Klein R., Welborn T.A. Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4-7 yr before clinical diagnosis. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:815–819. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meijer E., Bakker S.J., Halbesma N. Copeptin, a surrogate marker of vasopressin, is associated with microalbuminuria in a large population cohort. Kidney Int. 2010;77:29–36. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijer E., Bakker S.J., de Jong P.E. Copeptin, a surrogate marker of vasopressin, is associated with accelerated renal function decline in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2009;88:561–567. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b11ae4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boertien W.E., Meijer E., Zittema D. Copeptin, a surrogate marker for vasopressin, is associated with kidney function decline in subjects with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:4131–4137. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alehagen U., Dahlstrom U., Rehfeld J.F. Association of copeptin and N-terminal proBNP concentrations with risk of cardiovascular death in older patients with symptoms of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305:2088–2095. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller W.L., Hartman K.A., Grill D.E. Serial measurements of midregion proANP and copeptin in ambulatory patients with heart failure: incremental prognostic value of novel biomarkers in heart failure. Heart. 2012;98:389–394. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wannamethee S.G., Welsh P., Whincup P.H. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide but not copeptin improves prediction of heart failure over other routine clinical risk parameters in older men with and without cardiovascular disease: population-based study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:25–32. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nitenberg A., Paycha F., Ledoux S. Coronary artery responses to physiological stimuli are improved by deferoxamine but not by l-arginine in non–insulin-dependent diabetic patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries and no other risk factors. Circulation. 1998;97:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nitenberg A., Ledoux S., Valensi P. Impairment of coronary microvascular dilation in response to cold pressor–induced sympathetic stimulation in type 2 diabetic patients with abnormal stress thallium imaging. Diabetes. 2001;50:1180–1185. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alzahrani S.H., Ajjan R.A. Coagulation and fibrinolysis in diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2010;7:260–273. doi: 10.1177/1479164110383723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frankel D.S., Meigs J.B., Massaro J.M. Von Willebrand factor, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2008;118:2533–2539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.792986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufmann J.E., Oksche A., Wollheim C.B. Vasopressin-induced von Willebrand factor secretion from endothelial cells involves V2 receptors and cAMP. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:107–116. doi: 10.1172/JCI9516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerstein H.C., Miller M.E., Byington R.P. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerstein H.C., Miller M.E., Genuth S. Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:818–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schrier R.W., Gross P., Gheorghiade M. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2099–2112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gheorghiade M., Konstam M.A., Burnett J.C., Jr. Short-term clinical effects of tolvaptan, an oral vasopressin antagonist, in patients hospitalized for heart failure: the EVEREST Clinical Status Trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1332–1343. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary References

- 49.Cederholm J., Eeg-Olofsson K., Eliasson B. Risk prediction of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a risk equation from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):2038–2043. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindholm E., Agardh E., Tuomi T. Classifying diabetes according to the new WHO clinical stages. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17(11):983–989. doi: 10.1023/a:1020036805655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ludvigsson J.F., Andersson E., Ekbom A. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Board of Health and Welfare; Stockholm: 2003. A finger on the pulse. Monitoring public health and social conditions in Sweden 1992-2002. (The report can be downloaded from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2003/2003-118-16) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johansson L.A., Westerling R. Comparing Swedish hospital discharge records with death certificates: implications for mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wettermark B., Hammar N., Fored C.M. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726–735. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]