Abstract

Aims

To quantify the effect of negative affect (NA), when manipulated experimentally, upon smoking as measured within laboratory paradigms. Quantitative meta-analyses tested the effects of NA vs. neutral conditions on 1) latency to smoke and 2) number of puffs taken.

Methods

Twelve experimental studies tested the influence of NA induction, relative to a neutral control condition (N = 1,190; range = 24–235). Those providing relevant data contributed to separate random effects meta-analyses to examine the effects of NA on two primary smoking measures: 1) latency to smoke (nine studies) and 2) number of puffs taken during ad lib smoking (eleven studies). Hedge’s g was calculated for all studies through the use of post-NA cue responses relative to post-neutral cue responses. This effect size estimate is similar to Cohen’s d, but corrects for small sample size bias.

Results

NA reliably decreased latency to smoke (g = −.14; CI = −.23 to −.04; p = .007) and increased number of puffs taken (g = .14; CI = .02 to .25; p = .02). There was considerable variability across studies for both outcomes (I2 = 51% and 65% for latency and consumption, respectively). Potential publication bias was indicated for both outcomes, and adjusted effect sizes were smaller and no longer statistically significant.

Conclusions

In experimental laboratory studies of smokers, negative affect appears to reduce latency to smoking and increase number of puffs taken but this could be due to publication bias.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking, conditioned stimuli, affect, cue-reactivity

Cue-Reactivity Paradigm and Smoking Motivation

Over four decades of research has focused on the role of situational stimuli on smoking motivation (1, 2). The cue-reactivity paradigm is an internally valid method to manipulate and test causal effects of situational stimuli, relative to a control comparison (3, 4). The majority of these laboratory analogue studies of drug-seeking behavior have focused on responses to smoking-related stimuli (e.g., cigarettes, people smoking, paraphernalia), and these exteroceptive cues have large magnitude effects (d = 1.18) on self-reported craving (5). Despite these robust responses among current smokers, the relationship between cue-provoked cravings and smoking behavior remains unclear (6–8).

Acute Negative Affect and Smoking Motivation

The limited predictive utility of smoking-specific cue reactivity has led to suggestions that responses to cues that are non-specific to smoking may prove more informative (9). Negative affect (NA) is perhaps the most studied among these cues (for qualitative reviews see 10, 11–15). Negative affect is often conceptualized broadly (e.g., superordinate to mood, emotion, stress, and impulses; 16), with subcomponents generally differentiated in terms of duration (state vs. trait) and arousal/activation (low vs. high). Herein, we focus on states of negative affect in the broadest sense, including both high (e.g., distressed, anxious, anger) and low (e.g., sadness, boredom) levels of arousal.

NA is central to many models of addiction (17–20), and acute increases of NA have been purported to be the prepotent motive maintaining drug dependence (21). Smokers may acquire situational NA (i.e., as a function of stressors) as an interoceptive cue to smoke through associative conditioning that occurs after repeated pairings of smoking to alleviate aversive withdrawal symptoms. We recently concluded a meta-analysis demonstrating that experimental manipulations of NA reliably increase craving to smoke (22), and that these effects are independent of nicotine deprivation. However, this prior meta-analysis did not examine the effect of NA manipulation on smoking behavior, which has received valid criticism (23).

Across multiple research methodologies, NA is known to be a consistent barrier to smoking cessation. Within cross-sectional designs that use retrospective self-report surveys, NA is among the most frequently reported precipitants to relapse (24–31). This is consistent with prospective observational studies using ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which find NA to be the situational determinant most likely to precede a lapse (32). Furthermore, NA-related lapses are more likely to progress to relapse than lapses proceeded by other precipitants (33). Thus, there is a clear relationship between NA and smoking for individuals making a cessation attempt.

Less clear, however, is the extent to which NA predicts naturalistic smoking behavior among current smokers (i.e., in the absence of a quit attempt). Affect regulation is consistently endorsed as a primary motive for smoking within retrospective studies (34–37). This effect has been supported by one EMA study (38), but not observed in others (39, 40). Equivocal findings suggest that retrospective studies may be subject to recall bias, and call into question whether NA influences ad lib smoking among non-treatment seeking smokers.

The cue-reactivity paradigm offers another method to clarify the relationship between NA and ad lib smoking. Through experimental manipulation of NA, this approach can provide strong causal evidence to support (or reject) the hypothesis that NA increases smoking behavior. Two commonly assessed smoking indices following cue administration are latency to smoke and number of puffs, both of which serve as naturalistic measures of smoking (41, 42).

Current Study

Although the relationship between NA and smoking has been discussed in qualitative reviews (10–12, 15, 27), this relationship has yet to be quantified systematically. The primary aim of this review was to use meta-analytic methods to determine the effect size of smoking behavior resultant from NA manipulation. Specifically, we hypothesized that NA manipulations would reduce latency to smoke, and increase the number of puffs taken during ad lib smoking.

Methods

Study Acquisition

As part of a larger effort to identify all cue-reactivity studies (i.e., including those not focused on NA and smoking), the following terms were searched within PsycINFO, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Dissertation Abstracts: (smok* OR nicotine OR tobacco) AND (cue OR stimuli OR reactivity OR conditioned withdrawal OR conditioned responses OR craving OR urge OR stroop OR implicit OR response time OR dot-probe OR priming OR dual-task OR expectancy OR accessibility OR startle OR memory OR cognition OR affect OR mood OR topography OR psychophys* OR fMRI OR ERP). This search, along with bibliographic searches within pertinent studies and qualitative reviews, concluded in September of 2013, and yielded 10,969 abstracts that were then reviewed to determine relevance to the current study. Due to the breadth of the search terms used, the majority of these studies were excluded because it was clear from the abstract that they did not examine the relationship between NA and smoking. The 110 abstracts that mentioned NA in relation to smoking were read in full to determine if they met the criteria described below. Appendix A contains an enumerative flow diagram of study selection.

Studies meeting the following criteria were included in analyses: 1) sample included smokers; 2) comparison of a neutral cue to a NA cue, devoid of smoking-related content; 3) assessment of post-cue smoking behavior (i.e., latency to smoke and/or puffs taken); and 4) inclusion of statistics necessary to compute an effect size. Authors of relevant studies without the final criterion were contacted via email, and four of six studies provided this information.

Study Codification

Each study was coded independently by the third and fourth authors (88% agreement), and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the first author. The following study characteristics were extracted, when available: a) sample demographics; b) self-reported affect and craving; c) hours of nicotine deprivation (via pre-session smoking instructional set); d) gender composition (calculated as percent male); e) nicotine dependence (via cigarettes per day [CPD] and Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence scores [FTND]; 43); f) cue presentation modality; and g) how latency to smoke data were coded for participants who chose not to smoke at all during the lab session. We also codified the methodological quality (i.e., validity or risk of bias) for each study using a modified scale informed by Cochrane, PRISMA, and PEDro guidelines. This scale consisted of 12 dichotomous items that captured procedural (e.g., randomization, sample size justification, description of inclusion criteria, manipulation check) and statistical (e.g., description of analyses, selective reporting) aspects of the study. The average methodological quality score was 79% (range = 67 – 84%), with higher values representing higher quality design.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses standards were followed, and are listed in Appendix B (44). Individual study effect sizes and meta-analytic statistics were computed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (45). Separate random effects meta-analyses were conducted to assess experimental manipulations of NA upon latency to smoke, and number of puffs. Post-NA cue responses relative to post-neutral cue responses were used to calculate Hedge’s g, and a conservative correlation (.7) was assumed when calculating matched group effect sizes (46). Heterogeneity between effect sizes were indicated by the Q statistic and I2. The latter is an estimate of the proportion of variation that is due to true differences in the underlying effect (relative to sampling error), and values of 25%, 50%, and 75% reflect low, moderate, and high heterogeneity. The impact of publication bias was examined visually via inspection of funnel plots, and statistically through Begg–Mazumdar rank correlation test (47), Egger’s test (48), and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill approach (49). If bias is detected the trim and fill approach suggests the number of missing studies, imputes them, and computes an adjusted effect size.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The entire sample consisted of 12 studies (N = 1,190), the majority of which contributed to both meta-analyses (see Figures 1–2). Unfortunately, the small number of studies precluded formal tests of moderation (e.g., by type of NA induction), but study characteristics are presented in Table 1 (for included studies see 50–61). Almost three-fifths (58%) of studies used within-subjects designs. On average, study participants were 33 years of age, 52% male, smoked 19 CPD, and were moderately nicotine dependent (FTND = 5). All studies were based on non-treatment seeking samples. With the exception of one study, pre-session nicotine deprivation was less than 60 minutes, so participants were minimally nicotine-deprived. All studies measured self-reported affect, and 75% measured craving. There was considerable variability for the type of NA manipulations employed, including: picture presentation (k = 5), speech preparation/presentation (k = 4), music (k = 3), pain (k = 2), imagery (k = 1) and film (k = 1). The majority of studies tested NA inductions that combined more than one method simultaneously, thereby limiting the ability to detect what may be the most effective NA inductions. The length of ad lib smoking periods ranged from 10 to 50 minutes. Of the nine studies that examined latency to smoke, four studies did not report how data were coded for participants who chose not to smoke at all during the lab session (e.g., excluded participants, use maximum time). This was not applicable for two studies which asked participants to take at least one puff during the ad lib smoking period (i.e., all participants smoked), one specified that the maximum time allotted for the smoking period was entered as latency, and two studies used survival analysis. The number of cigarettes available during the ad lib smoking period ranged from 1 to 8, and to standardize comparisons we focused on the first cigarette smoked (e.g., 52, 54, 57). In the single study that tested more than one NA induction method independently, a composite score that accounted for the multiple NA manipulations was used to calculate the study effect size (53). In addition to NA manipulations, four (33%) of the studies also included positive affect inductions, and four (33%) had smoking-specific cues (data not presented here).

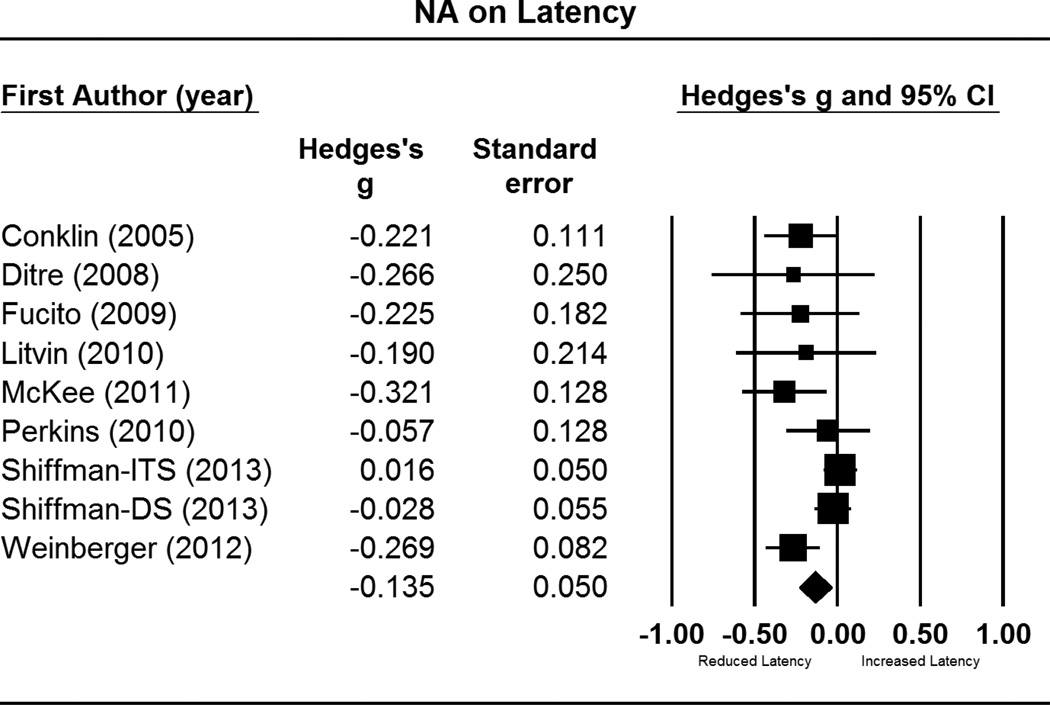

Figure 1.

Forest plot for comparisons of post-NA cue latency to smoke, relative to post-neutral cue latency. This includes effect sizes (g), standard errors, variances, 95% confidence intervals, Z scores, and p-values. Effect sizes to the right of zero indicate longer latency in response to NA cues, relative to neutral cues. Confidence intervals that do not include zero reflect significant differences. Summary statistics are reported in the final row, computed via random effects meta-analysis.

Notes: ITS = intermittent smokers; DS = daily smokers

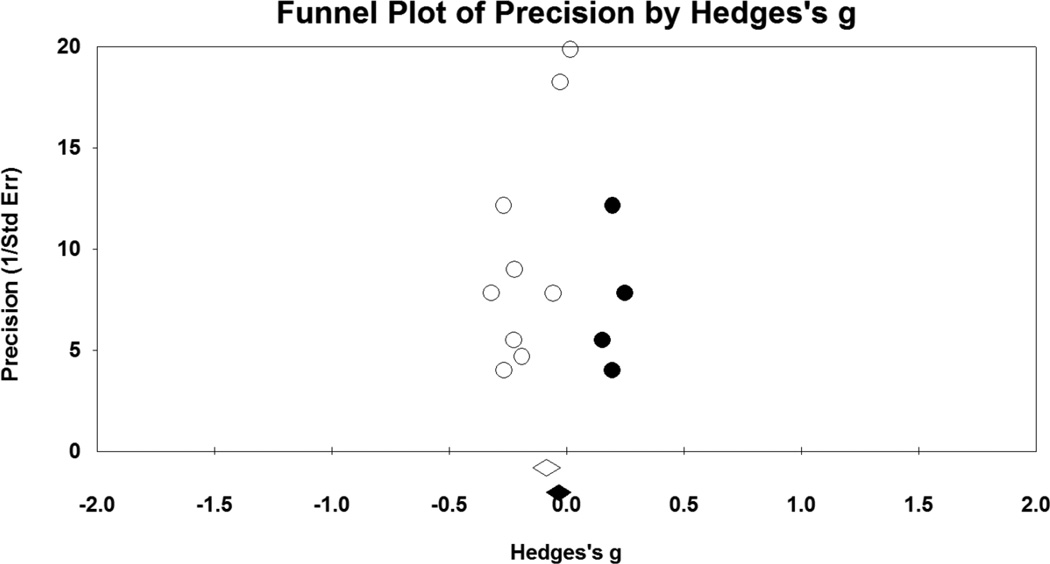

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for comparisons of post-NA cue latency to smoke, relative to post-neutral cue latency. Open circles represent values for individual studies, and the open diamond is pooled effect size for all nine studies. Solid circles are imputed studies suggested by the trim and fill method, and the solid diamond is the adjusted pooled effect size.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| First Author | Year | N | Age | CPD | FTND | WD (minutes) |

Study Design |

Cues Included | NA cue | Neutral Cue | Smoking Period (minutes) |

Latency Coding For Participants Who Did Not Smoke |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conklin | 2005 | 48 | 29 | 20 | 5 | 30 | W | NA, PA | IAPS & music (high arousal) | IAPS & music (low arousal) | 10 | unclear if this occurred, or how coded |

| Ditre | 2008 | 66 | 36 | 23 | NR | 60 | B | NA, Smoking | Cold pressor | Room temperature water | 10 | all asked to take at least one puff |

| Fucito | 2009 | 121 | 34 | 15 | NR | 60 | B | NA | Sad movie clip of child watching father die (Champ) | Nature video clip | unclear | unclear if this occurred, or how coded |

| Litvin | 2010 | 88 | 39 | 22 | 6 | 30 | B | NA, Smoking | Speech preparation | Rate art (landscapes) | unclear | all asked to take at least one puff |

| McKee | 2011 | 37 | 38 | 18 | 6 | 660 | W | NA | Personal imagery (stressful) | Personal imagery (relaxing/neutral) | 50 | maximum time used |

| Perkins | 2010 | 104 | 27 | 19 | 5 | 0 | W | NA | Composite: digit recall; public-speaking; IAPS (high arousal) | IAPS (neutral) | 10 | unclear if this occurred, or how coded |

| Perkins | 2012 | 164 | 28 | 16 | 5 | 0 | W | NA | IAPS & music (high arousal) | IAPS & music (pleasant) | 14 | not measured |

| Rose | 1983 | 15 | 38 | 33 | NR | 0 | W | NA, Attention | 20 minute comedy monologue preparation for 3 minute performance | Sit and read magazines | 10 | not measured |

| Schachter | 1977 | 24 | 25 | 23 | NR | 40 | B | NA | Painful shock | Low level (no pain) shock | 35 | not measured |

| Shiffman-ITS | 2013 | 235 | NR | 4 | NR | 0 | W | NA, PA, Smoking, Alcohol, Smoking Prohibition | IAPS | IAPS, Gilbert & Rabinovich, and iStock photos | 15 | survival analyses |

| Shiffman-DS | 2013 | 198 | 41 | 16 | NR | 0 | W | NA, PA, Smoking, Alcohol, Smoking Prohibition | IAPS | IAPS, Gilbert & Rabinovich, and iStock photos | 15 | survival analyses |

| Weinberger | 2012 | 90 | 26 | 17 | 5 | 1 | B | NA, PA | Music | Rest | 30 | unclear if this occurred, or how coded |

Notes: ITS = intermittent smokers; DS = daily smokers; PA = positive affect; NA = negative affect; W = within-subjects; B = between-subjects; TSST = Trier Social Stress Test; IAPS = International Affective Picture System; CPD = cigarettes per day; FTND = nicotine dependence score; WD = time in withdrawal from nicotine; NR = not reported

Primary Analyses

Latency to smoke

As depicted in Figure 1, NA manipulations yielded small but statistically significant effects for decreasing latency to smoke (g = −.14; CI = −.23 to −.04; p = .007). There was moderate heterogeneity in effect sizes, as seen by the significant Q statistic (Q = 16.37, p = .04) and amount of true variance accounted for (I2 = 51%). Publication bias was indicated by Egger’s test (p = .02) and the trim and fill method. Imputation of four studies was suggested (see Figure 2), which reduced the summary statistic substantially (adjusted g = −.05, CI = −.15 – .05).

Number of puffs

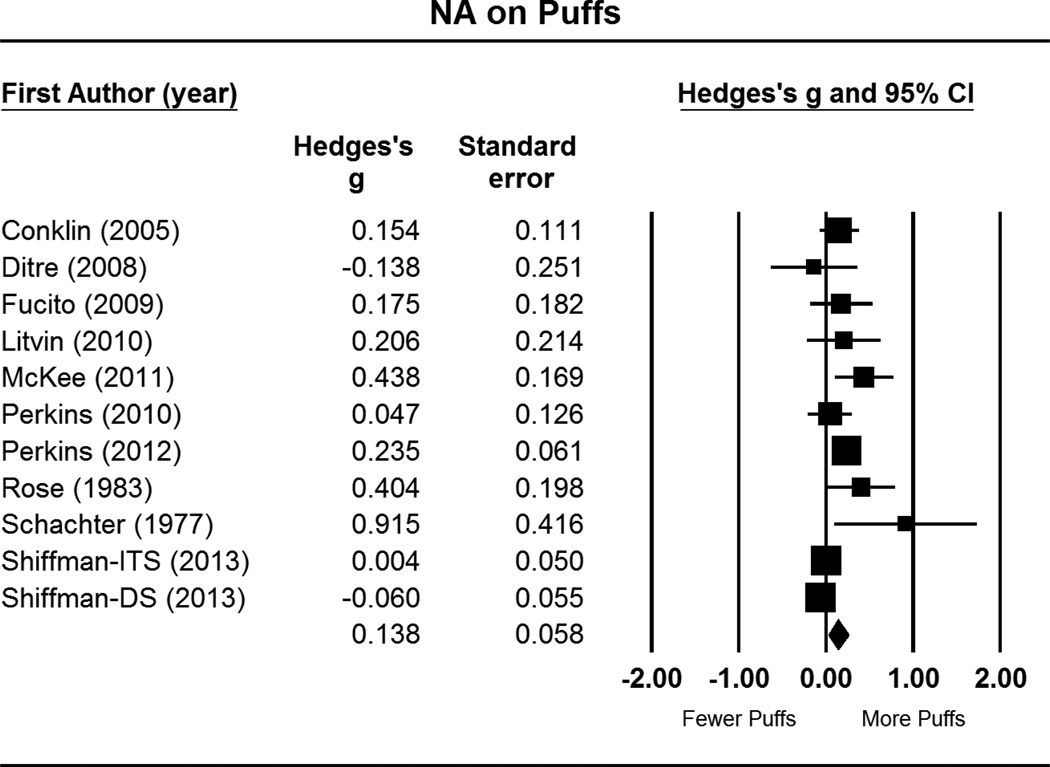

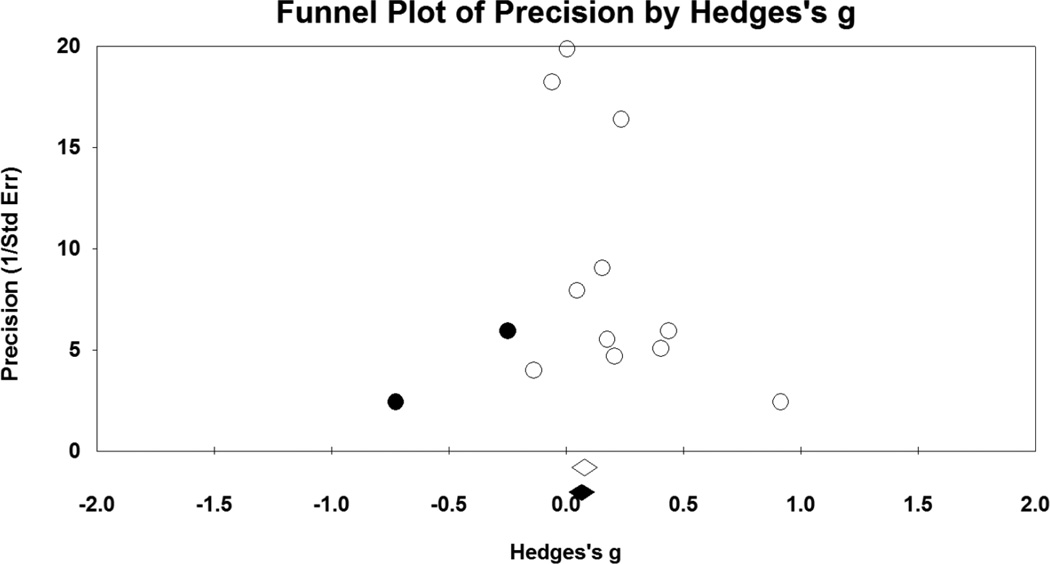

As depicted in Figure 3, NA manipulations yielded small but statistically significant effects for increasing number of puffs taken during the ad libitum smoking period (g = .14, CI = .02 – .25; p = .02). There was moderate-to-high heterogeneity in effect sizes, as seen by the significant Q statistic (Q = 28.38, p = .002) and amount of true variance accounted for (I2 = 65%). Again, Egger’s test (p = .047) and the trim and fill method indicated potential bias. Imputation of two studies was suggested (see Figure 4), which reduced the summary statistic (adjusted g = .10, CI = −.02 – .22).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for number of puffs, as function of post-NA cue puff frequency relative to post-neutral cue puffs. This includes effect sizes (g), standard errors, variances, 95% confidence intervals, Z scores, and p-values. Effect sizes to the right of zero indicate greater number of puffs in response to NA cues, relative to neutral cues. Confidence intervals that do not include zero reflect significant differences. Summary statistics are reported in the final row, computed via random effects meta-analysis.

Notes: ITS = intermittent smokers; DS = daily smokers

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for number of puffs, as function of post-NA cue puff frequency relative to post-neutral cue puffs. Open circles represent values for individual studies, and the open diamond is pooled effect size for all eleven studies. Solid circles are imputed studies suggested by the trim and fill method, and the solid diamond is the adjusted pooled effect size.

Discussion

To characterize the effects of acute NA on smoking behavior, we quantitatively synthesized cue-reactivity studies that experimentally manipulated NA and measured smoking behavior shortly thereafter. As expected, we observed a clear cause-effect relationship with respect to controlled laboratory manipulations of NA (relative to neutral cues) increasing smoking. Specifically, NA induction decreased latency to smoke, and increased number of puffs taken. However, these findings may be called into question, given that Egger’s test (48), and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill approach (49) indicated the potential presence of publication bias for both outcomes. Furthermore, the trim and fill approach found that the effects of NA on smoking were no longer significant after accounting for this bias. If it is the case that non-significant studies went unpublished, then the small effect sizes observed herein are likely to be smaller (i.e., less of an influence of NA on smoking). We interpreted the trim and fill findings with caution given that this method has been found to lead to spurious adjustments when applied to a heterogeneous set of studies (62), as was the case here. Alternatively, the pattern observed by these publication bias indices may be due to a small-study effect, and the smaller studies may have really found larger effects for NA manipulations. Moderation analyses could help test whether the relationship between sample size and effect size better reflects publication bias or a small-study effect (63), but as described earlier, none were conducted due to the limited number of studies. This draws attention to the importance of additional studies. Given the uncertainty of the publication bias analyses, and the number of studies that were published despite non-significant findings, we conclude that the NA manipulations had real, albeit small, effects on ad lib smoking. Thus, findings support theories in which the interoceptive state of NA is a contributory mechanism involved in the maintenance of drug dependence, including smoking (21).

It is noteworthy that the effect sizes were small in magnitude, and not as strong as the medium effect size observed from a previously reported meta-analysis of NA manipulations on cravings to smoke (22). It is hard to account for this divergence given the lack of complete overlap in studies that contributed to self-report vs. behavioral findings. This may reflect a weak relationship between craving and smoking, as found in a recent meta-analysis (64). Or it may reflect that greater time elapsed between the NA induction and the smoking behavior, given that craving assessments always preceded smoking assessments. Thus, there was greater opportunity for NA to subside before smoking occurred. It may also be the case that smokers are reluctant to smoke in the laboratory, perhaps due to the expanded coverage of indoor smoking bans and potential for social disapproval associated with smoking inside. Additionally, behavioral outcomes may be subject to greater variability due to individual differences (65), which is supported by the heterogeneity in effects sizes observed in the current study.

Unfortunately, there were too few studies to test potential moderators of the relationship between NA induction and smoking. As this literature expands, it is imperative to determine important individual differences and methodology moderators. For example, mode of presentation (e.g., pictures, video, imagery, speech) was found to moderate the influence of NA on craving (22). Amount of nicotine deprivation, duration of the ad lib smoking period, concurrent administration of the NA induction during this period, and provision of incentives to resist smoking are other potential candidates. Additionally, smokers with psychiatric (e.g., mood, anxiety) and/or medical conditions (e.g., chronic pain) marked by affective dysregulation experience more frequent/and or severe occurrences of NA and may have limited coping strategies (i.e., alternatives to smoking), thereby increasing the likelihood of developing an association between NA and smoking (66).

Potential Implications

Studies that include both NA and smoking-specific cues suggest that reactivity to NA may have more utility for predicting smoking behavior. For example, NA-induced cravings predict smoking better than cravings produced by drug-specific stimuli when measured via ad lib smoking in the lab (67), and lapses in the natural environment (32). A potential explanation for this is that reactivity to drug-specific stimuli may extinguish rather quickly following cessation (68–70), and therefore may be more useful for predicting continued use rather than relapse. In contrast, interoceptive cues, such as NA, may be more resistant to change (71). This suggests that NA reactivity may serve as a stable individual difference factor that underlies susceptibilty to relapse. Reduction of NA-induced smoking tested within the lab may serve as a proxy for treatment efficacy, and this laboratory model may be useful for screening potential cessation interventions prior to full scale clinical trials (72–78). Screening paradigms have been used to identify novel pharmacotherapies, but have yet to be applied for the development of behavioral interventions.

Given that NA is largely devoid of environmental constraints (i.e., can occur anywhere), cessation treatments might benefit by including strategies that: 1) prevent exposure to NA, 2) teach patients how to regulate NA, and/or 3) extinguish the relationship between NA and drug seeking. Traditional cognitive-behavioral treatments (CBT) have effectively approached the first and second aim with skills training that encourages avoidance of stressors and the use of coping strategies to mitigate NA (79). Several third wave treatments (e.g., mindfulness, distress tolerance, or acceptance based strategies) offer promising approaches with respect to weakening the relationship between NA and substance use (80). These interventions teach smokers to experience NA without acting upon it (81–83), and may have better long term outcomes than traditional CBT (84). These methods have been found to be mediated by reducing the avoidance of internal states and inflexibility between these states and substance use (82). This suggests that these treatments may serve as a form of cue-exposure with response prevention, which has long been proposed as a method to decrease cue-provoked cravings (85). Although cue-exposure interventions have not proven efficacious to date (86), third wave interventions may offer novel insights in that they target conditioned responses to NA instead of smoking-specific cues.

Limitations and Future Directions

The constituent studies present potential limitations to generalizability, as they tested contrived NA manipulations within controlled settings. This is in contrast to EMA studies which test naturally occurring NA. Therefore, the internal validity gained by the cue-reactivity paradigm comes with potential loss of external validity. Another distinction between experimental and EMA studies is that laboratory studies only provide the opportunity to smoke after several minutes of exposure to a stressor. Naturalistic smoking may instead occur with closer proximity, or in anticipation of, a stressor and prevent conscious awareness of NA (21). Furthermore, the samples included in the meta-analyses were non-treatment seeking, relatively young, and with the exception of one study were heavy smokers. Thus, it is unclear how the current findings may generalize to other types of smokers (e.g., non-daily, treatment seeking).

Notably, only two of the twelve studies tested low arousal NA manipulations (e.g., sadness). This pattern is consistent with experimental studies that examined NA with respect to craving, and limits the ability to elucidate the role of arousal. That is, we have clear evidence that high arousal NA (e.g., anxiety, distress) impacts smoking motivation, but it is unclear if this is due to increased arousal or unpleasantess caused by the NA manipulations. A study that comprehensively examines arousal (high/low) and valence (positive/negative) would help disentangle the unique components of affect, and determine those most critical to nicotine dependence.

Finally, as we reviewed the nine studies that examined latency to smoke we found that it was often unclear whether all participants chose to smoke during the lab session, and how data were coded for those that did not. Two studies avoided this by having participants to take at least one puff, but this is likely to interfere with naturalistic smoking and could influence the magnitude of experimental effects. Informing participants that they are free to smoke, but do not have to, would provide a context that more closely resemble real world choices. When given the option to smoke, survival analyses are most appropriate given that the data for participants who chose not to smoke are right censored. We recommend that future studies that examine latency to smoke report the number of participants who do not smoke, assess and report reasons for not smoking (e.g., prefer not to smoke indoors), and consider the use of survival analyses.

Conclusions

Across the 12 studies reviewed, NA inductions decreased latency to smoke and increased number of puffs. Consistent with previous theory and retrospective self-report findings, our analyses provide evidence in support of a causal relationship between NA and smoking motivation. These findings support negative reinforcement models of addiction that emphasize the role of aversive states upon drug-seeking behavior (21).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest: Funding for this research was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse award F31 DA033058 (BWH), and R01 DA033459 (BF). Dr. Brandon has served on the Varenicline Advisory Board for Pfizer and consulted on the development of the online behavioral adjuvant for varenicline users. Dr. Drobes served as a reviewer for the Pfizer 2011 Global Research Awards for Nicotine Dependence (GRAND) program and has been paid to serve as an expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. Drs. Brandon and Drobes have also received research funding from Pfizer.

References

- 1.Tiffany ST, Warthen MW, Goedeker KC. The functional significance of craving in nicotine dependence. Nebr Symp Motiv. 2009;55:171–197. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78748-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman CP. External and internal cues as determinants of the smoking behavior of light and heavy smokers. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1974;30:664–672. doi: 10.1037/h0037440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM, Pedraza M, Abrams DB. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:133–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drummond D, Tiffany ST, Glautier SE, Remington BE. Addictive behaviour: Cue exposure theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins KA. Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence? Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2009;104:1610–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins KA. Subjective reactivity to smoking cues as a predictor of quitting success. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14:383–387. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wray JM, Gass JC, Tiffany ST. A systematic review of the relationships between craving and smoking cessation. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2013;15:1167–1182. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiffman S. Responses to smoking cues are relevant to smoking and relapse. Addiction. 2009;104:1617–1618. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmody TP, Vieten C, Astin JA. Negative affect, emotional acceptance, and smoking cessation. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:499–508. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yucel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha R. Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addiction biology. 2009;14:84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassel JD, Veilleux JC, Wardle MC, Yates MC, Greenstein JE, Evatt DP, et al. Negative Affect and Addiction. Stress and Addiction: Biological and Psychological Mechanisms. San Diego, CA US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross JJ. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stasiewicz PR, Maisto SA. Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1993;24:337–356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wills TA, Shiffman S, Shiffman S, Wills TA. Coping and substance use: A conceptual framework. Coping and substance use. 1985:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heckman BW, Kovacs MA, Marquinez NS, Meltzer LR, Tsambarlis ME, Drobes DJ, et al. Influence of affective manipulations on cigarette craving: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2013;108:2068–2078. doi: 10.1111/add.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiffman S Commentary on Heckman. Negative affect increases craving-Questions about the relationship of affect, craving and smoking. Addiction. 2013;108:2079–2080. doi: 10.1111/add.12363. (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baer JS, Kamarck T, Lichtenstein E, Ransom CC., Jr Prediction of smoking relapse: analyses of temptations and transgressions after initial cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:623–627. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baer JS, Lichtenstein E. Classification and prediction of smoking relapse episodes: an exploration of individual differences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:104–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borland R. Slip-ups and relapse in attempts to quit smoking. Addictive behaviors. 1990;15:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brandon TH. Negative affect as motivation to smoke. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1994;3:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings C, Gordon JR, Marlatt GA. Relapse: Prevention and prediction. The addictive behaviors. 1980:291–321. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummings KM, Giovino G, Jaen CR, Emrich LJ. Reports of smoking withdrawal symptoms over a 21 day period of abstinence. Addictive behaviors. 1985;10:373–381. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(85)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Connell KA, Martin EJ. Highly tempting situations associated with abstinence, temporary lapse, and relapse among participants in smoking cessation programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:367–371. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: a situational analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Richards TJ. Progression from a smoking lapse to relapse: prediction from abstinence violation effects, nicotine dependence, and lapse characteristics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:993–1002. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Copeland AL, Brandon TH, Quinn EP. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:484. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frith CD. Smoking behaviour and its relation to the smoker's immediate experience. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1971;10:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1971.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikard FF, Green DE, Horn D. A scale to differentiate between types of smoking as related to the management of affect. Substance Use & Misuse. 1969;4:649–659. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiffman S. Assessing smoking patterns and motives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:732–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carter BL, Lam CY, Robinson JD, Paris MM, Waters AJ, Wetter DW, et al. Real-time craving and mood assessments before and after smoking. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2008;10:1165–1169. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: an analysis of unrestricted smoking patterns. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:166–171. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKee SA. Developing human laboratory models of smoking lapse behavior for medication screening. Addiction biology. 2009;14:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2.2. Englewood Cliffs: Biostat. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research / Robert Rosenthal. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; c1991. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and Fill: A Simple Funnel-Plot–Based Method of Testing and Adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ditre JW, Brandon TH. Pain as a motivator of smoking: effects of pain induction on smoking urge and behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:467–472. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Litvin EB, Brandon TH. Testing the influence of external and internal cues on smoking motivation using a community sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:61–70. doi: 10.1037/a0017414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKee SA, Sinha R, Weinberger AH, Sofuoglu M, Harrison EL, Lavery M, et al. Stress decreases the ability to resist smoking and potentiates smoking intensity and reward. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:490–502. doi: 10.1177/0269881110376694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Conklin CA, Sayette MA, Giedgowd GE. Acute negative affect relief from smoking depends on the affect situation and measure but not on nicotine. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiffman S, Dunbar M, Kirchner T, Li X, Tindle H, Anderson S, et al. Smoker reactivity to cues: effects on craving and on smoking behavior. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2013;122:264–280. doi: 10.1037/a0028339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perkins KA, Giedgowd GE, Karelitz JL, Conklin CA, Lerman C. Smoking in response to negative mood in men versus women as a function of distress tolerance. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14:1418–1425. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinberger AH, McKee SA. Gender differences in smoking following an implicit mood induction. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14:621–625. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shiffman S, Dunbar MS, Kirchner TR, Li X, Tindle HA, Anderson SJ, et al. Cue reactivity in non-daily smokers: effects on craving and on smoking behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;226:321–333. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2909-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conklin CA, Perkins KA. Subjective and reinforcing effects of smoking during negative mood induction. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:153–164. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fucito LM, Juliano LM. Depression moderates smoking behavior in response to a sad mood induction. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:546–551. doi: 10.1037/a0016529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rose JE, Ananda S, Jarvik ME. Cigarette smoking during anxiety-provoking and monotonous tasks. Addictive behaviors. 1983;8:353–359. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schachter S, Silverstein B, Perlick D. 5. Psychological and pharmacological explanations of smoking under stress. Journal of experimental psychology General. 1977;106:31–40. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.106.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J, Olkin I. Adjusting for publication bias in the presence of heterogeneity. Statistics in medicine. 2003;22:2113–2126. doi: 10.1002/sim.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borenstein m. Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Software for Publication Bias. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis; pp. 193–220. (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gass JC, Motschman CA, Tiffany ST. The relationship between craving and tobacco use behavior in laboratory studies; A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0036879. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gilbert DG. Smoking: individual difference, psychopathology, and emotion. Taylor & Francis; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, Meagher MM. Pain, nicotine, and smoking: research findings and mechanistic considerations. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:1065–1093. doi: 10.1037/a0025544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, DeSantis S, Gray KM, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HR. Laboratory-based, cue-elicited craving and cue reactivity as predictors of naturally occurring smoking behavior. Addictive behaviors. 2009;34:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collins BN, Nair US, Komaroff E. Smoking cue reactivity across massed extinction trials: negative affect and gender effects. Addictive behaviors. 2011;36:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Connell KA, Shiffman S, Decarlo LT. Does extinction of responses to cigarette cues occur during smoking cessation? Addiction. 2011;106:410–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Unrod M, Drobes DJ, Stasiewicz PR, Ditre JW, Heckman B, Miller RR, et al. Decline in cue-provoked craving during cue exposure therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2014;16:306–315. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vinci C, Copeland AL, Carrigan MH. Exposure to negative affect cues and urge to smoke. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:47–55. doi: 10.1037/a0025267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lerman C, LeSage MG, Perkins KA, O'Malley SS, Siegel SJ, Benowitz NL, et al. Translational research in medication development for nicotine dependence. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6:746–762. doi: 10.1038/nrd2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKee SA. Developing human laboratory models of smoking lapse behavior for medication screening. Addiction biology. 2009;14:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perkins K, Stitzer M, Lerman C. Medication screening for smoking cessation: A proposal for new methodologies. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:628–636. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Fonte CA, Mercincavage M, Stitzer ML, Chengappa KN, et al. Cross-validation of a new procedure for early screening of smoking cessation medications in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:109–114. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Karelitz JL, Jao NC, Chengappa KN, Sparks GM. Sensitivity and specificity of a procedure for early human screening of novel smoking cessation medications. Addiction. 2013;108:1962–1968. doi: 10.1111/add.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perkins KA, Lerman C, Stitzer M, Fonte CA, Briski JL, Scott JA, et al. Development of procedures for early screening of smoking cessation medications in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:216–221. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McKee SA, Weinberger AH, Shi J, Tetrault J, Coppola S. Developing and validating a human laboratory model to screen medications for smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:1362–1371. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fiore MCJC, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, Dorfman SF, Froelicher ES, Goldstein MG, Healton CG, Henderson PN, Heyman RB, Koh HK, Kottke TE, Lando HA, Mecklenburg RE, Mermelstein RJ, Mullen PD, Orleans CT, Robinson L, Stitzer ML, Tommasello AC, Villejo L, Wewers ME, Murray EW, Bennett G, Heishman S, Husten C, Morgan G, Williams C, Christiansen BA, Piper ME, Hasselblad V, Fraser D, Theobald W, Connell M, Leitzke C. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53:1217–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Mindfulness Training Targets Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Addiction at the Attention-Appraisal-Emotion Interface. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2014;4:173. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zvolensky MJ, Yartz AR, Gregor K, Gonzalez A, Bernstein A. Interoceptive exposure-based cessation intervention for smokers high in anxiety sensitivity: A case series. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;22:346–365. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen-Hall ML, et al. Acceptance-Based Treatment for Smoking Cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:689–705. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: Rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32:302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hernández-López M, Luciano MC, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: A preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ. Coping-skills training and cue-exposure therapy in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23:107–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.