Abstract

Aims

To determine the feasibility, safety, and clinical efficacy of intravitreal 0.7-mg dexamethasone implants (Ozurdex) in patients with refractory cystoid macular edema after uncomplicated cataract surgery.

Methods and materials

In this study, 11 eyes of 11 patients affected by pseudophakic cystoid macular edema refractory to medical treatment were treated with a single intravitreal injection of a dexamethasone implant. Follow-up visits involved Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity testing, optical coherence tomography imaging, and ophthalmoscopic examination.

Results

The follow-up period was six months. The mean duration of cystoid macular edema before treatment with Ozurdex was 7.7 months (range, 6–10 months). The baseline mean best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 0.58 ± 0.17 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR). The mean BCVA improved to 0.37 ± 0.16 logMAR (p = 0.008) and 0.20 ± 0.13 logMAR (p = 0.001) after 1 and 3 months, respectively. At the last follow-up visit (6-month follow-up), the mean BCVA was 0.21 ± 0.15 logMAR (p = 0.002). The mean foveal thickness at baseline (513.8 μm, range, 319–720 μm) decreased significantly (308.0 μm; range, 263–423 μm) by the end of the follow-up period (p < 0.0001). Final foveal thickness was significantly correlated with baseline BCVA (r = 0.57, p = 0.002). No ocular or systemic adverse events were observed.

Conclusions

Short-term results suggest that the intravitreal dexamethasone implant is safe and well tolerated in patients with pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Treated eyes had revealed a significant improvement in BCVA and decrease in macular thickness by optical coherence tomography.

Keywords: Intravitreal dexamethasone implant, Ozurdex, Refractory pseudophakic cystoid macular edema, Cataract surgery

Introduction

Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a common cause of decreased vision following complicated or uncomplicated cataract surgery. It may be revealed angiographically after uneventful intracapsular and extracapsular cataract surgery in up to 60% and 30% of cases, respectively; however, the incidence of clinical CME is much lower (0.1–13%).1–4 The rate of angiographic and clinical CME after phacoemulsification cataract surgery is even lower at 20% and 1–2%, respectively.4,5

CME usually resolves spontaneously in approximately 90% of eyes, and only a small subset of patients suffer permanent visual morbidity.4,6 Considering the large number of patients undergoing cataract surgery, this small percentage of patients represents a population large enough to drive ongoing research to identify appropriate treatment strategies.4 Various treatment modalities including topical, systemic, periocular, and intraocular steroids; topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); and systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) have been used with different success rates to treat pseudophakic CME.3–5

The pathogenesis of pseudophakic CME is thought to be multifactorial. However, the major etiology appears to involve inflammatory mediators that are upregulated in the aqueous and vitreous humors after surgical manipulation. Inflammation breaks down the blood–aqueous and blood–retinal barriers, which leads to increased vascular permeability.7 Eosinophilic transudate accumulates in the outer plexiform and inner nuclear layers of the retina to create cystic spaces that coalesce to form larger pockets of fluid. In chronic CME, lamellar macular holes and subretinal fluid may also form.1

Glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone exert their anti-inflammatory effects by influencing multiple signal transduction pathways, including VEGF.8–11 By binding to cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors, corticosteroids in high doses increase the activation of anti-inflammatory genes, whereas, at low concentrations, they play a role in the suppression of activated inflammatory genes.9–12

The dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex; Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA) is a novel approach approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Union (EU) for the intravitreal treatment of macular edema (ME) after branch or central retinal vein occlusion and for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis affecting the posterior segment of the eye.13–15 Furthermore, its clinical efficacy has been documented in other diseases, such as diabetic ME and persistent ME associated with uveitis or Irvine–Gass syndrome.16–21 Compared with other routes of administration of dexamethasone analogs, intravitreal administration of this implant has been found to be more advantageous.22 The key features of the drug delivery system (DDS) are the sustained-release formulation of the poly lactic acid-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) matrix material, which dissolves completely in vivo, and the single-use applicator for intravitreal placement.23

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and feasibility of a single intravitreal injection of Ozurdex over 6 months in patients with persistent CME resulting from Irvine–Gass syndrome following uneventful cataract surgery.

Subjects and methods

This retrospective case series comprised 11 eyes of 11 patients with CME after cataract surgery refractory to current standard treatment who received a single injection of Ozurdex between June 2011 and March 2014 at King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar, Saudi Arabia. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Dammam and the ethics committee.

Informed consent was obtained from the patients. The nature of off-label use of Ozurdex for CME after cataract surgery and its potential side effects were extensively discussed with the patients before obtaining informed consent. Inclusion criteria included having previously undergone a wide range of treatment options, including oral CAIs, topical therapy with NSAIDs and corticosteroids, as well as intravitreal treatment either with anti-VEGF agents or with intravitreal triamcinolone. Refractory CME was defined as persistent CME with foveal thickness (FT) more than 250 μm and intraretinal cystic changes revealed by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), lasting for at least 90 days after initiation of treatment. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of systemic disease such as diabetes mellitus, history of other intraocular surgery before cataract extraction, glaucoma, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and vitreoretinal pathology such as epiretinal membrane or vitreomacular traction in the study eye, which could prevent improvement in visual acuity.

In all patients, the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was measured by using Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study charts and an ophthalmic examination, including slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Fluorescein angiography was also performed, showing leakage in the central region typical for CME. Baseline central retinal characteristics were analyzed by optical coherence tomography SD-OCT (Stratus OCT-3, Humphrey-Zeiss, San Leandro, CA) through a dilated pupil by a retina specialist. Retinal thickness of the 1.0-mm central retina was obtained from the macular thickness map for use in further calculations. Patients received a dexamethasone implant in the study eye at the baseline visit (day 1). The eye was prepared in the standard manner, using 5% povidone/iodine and topical antibiotics (0.3% ciprofloxacin). A single-use applicator with a 22-gauge needle was used to place a dexamethasone implant in the vitreous chamber through a self-sealing scleral injection. All injections were performed in the operating room. Following the injection, IOP and retinal artery perfusion were assessed, and patients were instructed to use topical antibiotics for 5 days (0.5% moxifloxacin). Patients were scheduled for regular postsurgical follow-up visits at day 2 and 1, 3, and 6 months. During these follow-up visits, the patients underwent BCVA examination, OCT imaging, and ophthalmoscopic examination.

The primary efficacy outcome measure was the change in BCVA and FT from baseline to 6 months. Statistical calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Mean changes from baseline FT and BCVA (converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution [logMAR]) were analyzed using paired t-tests. A 2-tailed test with an α level of 0.05 was used for all comparisons.

Results

This study included 11 eyes of 11 consecutive patients who were followed for 6 months. The baseline characteristics of the patients and study eyes are listed in the Table 1. The patients’ mean age was 59.4 ± 9.3 years, and 64% (7 of 11 patients) were men. All eyes had clinical CME at baseline examination. Patients were unresponsive to previous treatment with NSAIDs eyedrops, systemic CAIs, systemic or topical steroids, as well as intravitreal treatment either with anti-VEGF agents or with intravitreal triamcinolone. The mean duration of CME before treatment with Ozurdex was 7.7 months (range, 6–10 months).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical features of the patients.

| Patient No. | Gender | Age (Years) | Duration of CME Before Ozurdex Treatment (Months) | BCVA (logMAR) |

Foveal thickness (μm) |

Intraocular pressure (mmHg) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | ||||

| 1 | M | 55 | 8 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 319 | 281 | 277 | 265 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 2 | F | 53 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 566 | 351 | 288 | 293 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 15 |

| 3 | M | 70 | 6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 720 | 542 | 411 | 423 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 17 |

| 4 | M | 47 | 7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 445 | 330 | 283 | 294 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 13 |

| 5 | F | 73 | 6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 610 | 451 | 314 | 321 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 |

| 6 | M | 57 | 10 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 532 | 335 | 255 | 263 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 17 |

| 7 | M | 61 | 9 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 405 | 311 | 290 | 297 | 17 | 17 | 20 | 18 |

| 8 | F | 59 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 420 | 332 | 280 | 280 | 17 | 15 | 19 | 16 |

| 9 | M | 61 | 7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 435 | 308 | 293 | 300 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 14 |

| 10 | M | 58 | 6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 705 | 512 | 375 | 390 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| 11 | F | 62 | 9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 590 | 420 | 299 | 315 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

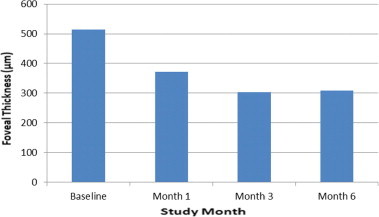

At baseline, the mean FT was 513.8 ± 134.9 μm. FT values decreased to 371.6 ± 91.9 μm (mean ± SD, p = 0.001) at 1 month and 302.6 ± 50.9 μm (p = 0.002) at 3 months, and increased slightly to 308.0 ± 54.5 μm (p = 0.031) at the end of the follow-up period. All of the FT reduction outcomes were statistically significant, with respect to baseline data (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1). The mean change from baseline FT was 142.2 μm (28% decrease) at 1 month and 211.2 μm (41% decrease) and 205.8 μm (40% decrease) at 3 months and 6 months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Mean changes from baseline foveal thickness. Improvement in foveal thickness observed at 1, 3, and 6 months after the injection.

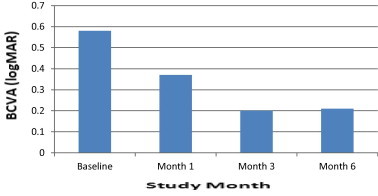

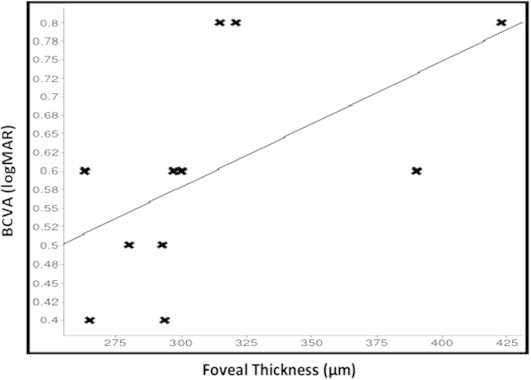

Furthermore, statistically significant improvement in BCVA was observed at 1 month after treatment with the dexamethasone implant and at each subsequent follow-up visit (Fig. 2). The baseline mean BCVA was 0.58 ± 0.17 logMAR. The mean BCVA improved to 0.37 ± 0.16 logMAR (p = 0.008) and 0.20 ± 0.13 logMAR (p = 0.001) after 1 and 3 months, respectively. At the last visit (6-month follow-up), the mean BCVA was 0.21 ± 0.15 logMAR (p = 0.002). Final foveal thickness (correlation coefficient, r = 0.57, p = 0.002) was significantly correlated with baseline BCVA (Fig. 3). No serious ocular or systemic side effects were noted during the observation period. There was no significant IOP elevation was observed in any patient.

Figure 2.

Mean changes from baseline BCVA. Improvement in BCVA observed at 1, 3, and 6 months after the injection.

Figure 3.

Final foveal thickness is positively correlated with baseline BCVA (r = 0.57, p = 0.002).

Discussion

CME can develop after modern cataract surgery. This complication is an important cause of suboptimal postoperative vision. Spontaneous resolution of the edema is the most likely natural course in this pathology. However, up to 2% of patients will not have spontaneous resolution of the edema and must thus be treated. Prompt treatment on recognition of the disorder is warranted, because if ME has been present for several months, there is likely irreversible changes in the macula.24

In the current study, intravitreal treatment with a dexamethasone implant safely reduced ME and improved visual acuity in a difficult-to-treat patient population with long-standing ME caused by Irvine–Gass syndrome. By 1 month after treatment with a dexamethasone implant, both mean FT and mean BCVA had improved from baseline, and the improvement remained statistically significant throughout the 6-month study period. The peak effectiveness of the dexamethasone implant was observed at 3 months after injection, when mean FT had decreased by 41% and the mean BCVA improved to 0.20 ± 0.13 logMAR from baseline. Some patients did not achieve normal FT and showed residual thickening at 6 months after injection; these patients may require a second intravitreal injection of the dexamethasone implant.

So far, only a few controlled clinical trials have evaluated treatments for ME associated with Irvine–Gass syndrome, including one on the use of vitrectomy for chronic aphakic CME.25 Intravitreal triamcinolone has been widely studied in diabetic ME and retinal vein occlusion; however, data supporting its use in pseudophakic CME are lacking. In 2003, Benhamou et al. reported the first study using 8-mg intravitreal triamcinolone to treat three cases of refractory chronic pseudophakic CME and showed that FT and visual acuity improved, but the effects were found to be transient.26 Another case series also reported transient benefits with 4-mg intravitreal triamcinolone.27 Clearly, one of the major limitations of intravitreal corticosteroids is its transient effect that necessitates repeated injections. This limitation can be overcome by the currently available sustained-release dexamethasone implant.

Several other studies have focused on the treatment of chronic pseudophakic CME that is refractory to other treatments. In 2008, Spitzer et al. showed that 1.25-mg intravitreal bevacizumab did not significantly improve visual outcomes in a series of 16 eyes with refractory pseudophakic CME, although a slight decrease in FT was observed.28 “Triple therapy” with intravitreal triamcinolone, intravitreal bevacizumab, and topical NSAIDs has been also shown to be effective, although the effects of the intravitreal medications were transient.29

Sustained DDSs have been developed to address the limitation of intravitreal corticosteroid injections. Ozurdex is an injectable, biodegradable intravitreal DDS that provides sustained release of preservative-free dexamethasone, a potent corticosteroid.30 In 2009, the FDA approved its use for the treatment of ME secondary to retinal vein occlusions, and in 2010, it was approved for the treatment of noninfectious posterior uveitis.13 A phase II study subgroup analysis investigated its efficacy in the treatment of persistent ME resulting from uveitis or pseudophakic CME.31 Twenty-seven patients with refractory pseudophakic CME were recruited and randomized to receive dexamethasone DDS 350 μg, dexamethasone DDS 700 μg, or observation. Eight patients showed at least a 10-letter improvement at day 90 and maintained the improvement at day 180. Significance testing was performed with combined data from pseudophakic CME and uveitis patients: an improvement in BCVA of at least 10 letters at day 90 was seen in 42% in the 350-μm group (p = 0.117) and 54% in the 700-μm group (p = 0.029).

Similarly, the results of this study are consistent with those results named above. Indeed, the dexamethasone implant resulted in sustained levels of dexamethasone release and biological activity for 6 months, with peak drug activity occurring over the first three months.18–20 The target population in the current study was difficult to treat because it included severe cases of long-standing ME after cataract surgery, which had failed to respond to a wide range of treatment options including oral CAIs, topical therapy with NSAIDs, and corticosteroids, as well as intravitreal treatment, most commonly intravitreal injection of the corticosteroid triamcinolone or anti-VEGF therapy.

The treatment approach for ME has been dynamic. Over the past few decades, corticosteroids have raised interest in the treatment of ME because of their anti-inflammatory effects and because they inhibit VEGF synthesis and reduce vascular permeability. Nonetheless, due to safety concerns (i.e., the risk of IOP elevation and cataract progression), in recent years, the use of corticosteroids has been drastically reduced in most developed countries. Recently, the safety profile of Ozurdex, which is currently approved for the treatment of retinal vein occlusion, was addressed in the GENEVA study.13 In the present series, no major side effects were recorded, and dexamethasone intravitreal implants were found to be well tolerated.

This study has several limitations—being a short-term, open-label, uncontrolled, and retrospective study—that precluded any estimation of the long-term efficacy or safety of intravitreal Ozurdex. A significant limitation of this study is that it included only a relatively small number of patients (11 eyes). In conclusion, intravitreal Ozurdex can induce regression of chronic refractory CME with concomitant improvement in visual acuity. This may be an excellent and safe treatment modality for patients with refractory CME unresponsive to previous treatment with NSAIDs eyedrops, systemic CAIs, systemic or topical steroids, as well as intravitreal treatment either with anti-VEGF agents or intravitreal triamcinolone.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Irvine S.R. A newly defined vitreous syndrome following cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953;36:599–619. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(53)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaide R.F., Yannuzzi L.A., Sisco L.J. Chronic cystoid macular edema and predictors of visual acuity. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:262–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin D.S., Lim J.I. Update on pseudophakic cystoid macular edema treatment options. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:467–472. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benitah N.R., Arroyo J.G. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:139–153. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181c551da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson B.A., Kim J.Y., Ament C.S., Ferrufino-Ponce Z.K., Grabowska A., Cremers S.L. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema; risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1550–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson D.R., Dellaporta A. Natural history of cystoid macular edema after cataract extraction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;77:445–447. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benitah N.R., Arroyo J.G. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:139–153. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181c551da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham S.M., Lawrence T., Kleiman A., Warden P., Medghalchi M., Tuckermann J. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1883–1889. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes P.J. Corticosteroid effects on cell signalling. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:413–426. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00125404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saklatvala J. Glucocorticoids: do we know how they work? Arthritis Res. 2002;4:146–150. doi: 10.1186/ar398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker B.R. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157:545–559. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nauck M., Karakiulakis G., Perruchoud A.P., Papakonstantinou E., Roth M. Corticosteroids inhibit the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;341:309–315. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haller J.A., Bandello F., Belfort R., Jr., Blumenkranz M.S., Gillies M., Heier J. Randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1134–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozurdex (dexamethasone). Ozurdex New FDA Drug Approval. 2009Medical Areas: Ophthalmology. Available at <https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/drug/1029/ozurdex-dexamethasone>. [Accessed 25.07.14].

- 15.PMLive. Allergan’s Ozurdex Approved by EMA. Available at http://www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/allergans_ozurdex_approved_by_ema_228541. Updated 28.07.10.

- 16.Haller J.A., Kuppermann B.D., Blumenkranz M.S., Williams G.A., Weinberg D.V., Chou C. Randomized controlled trial of an intravitreous dexamethasone drug delivery system in patients with diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:289–296. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyer D.S., Faber D., Gupta S., Patel S.S., Tabandeh H., Li X.Y. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for treatment of diabetic macular edema in vitrectomized patients. Retina. 2011;31:915–923. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318206d18c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang-Lin J.E., Attar M., Acheampong A.A., Robinson M.R., Whitcup S.M., Kuppermann B.D. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a sustained-release dexamethasone intravitreal implant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:80–86. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraiya N.V., Goldstein D.A. Dexamethasone for ocular inflammation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1127–1131. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.571209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang-Lin J.E., Burke J.A., Peng Q., Lin T., Orilla W.C., Ghosn C.R. Pharmacokinetics of a sustained-release dexamethasone intravitreal implant in vitrectomized and nonvitrectomized eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4605–4609. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowder C., Belfort R., Jr, Lightman S., Foster C.S., Robinson M.R., Schiffman R.M. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for noninfectious intermediate or posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:545–553. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kodama M., Numaga J., Yoshida A. Effects of a new dexamethasone-delivery system (Surodex) on experimental intraocular inflammation models. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:927–933. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0753-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivaprasad S., McCluskey P., Lightman S. Intravitreal steroids in the management of macular oedema. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:722–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reis A., Birnbaum F., Hansen L.L., Reinhard T. Successful treatment of cystoid macular edema with valdecoxib. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fung W.E. Vitrectomy for chronic aphakic cystoid macular edema: results of a national, collaborative, prospective, randomized investigation. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benhamou N., Massin P., Haouchine B. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory pseudophakic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:246–249. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01938-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conway M.D., Canakis C., Livir-Rallatos C. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for refractory chronic pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitzer M.S., Ziemssen F., Yoeruek E. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab in treating postoperative pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren K.A., Bahrani H., Fox J.E. NSAIDs in combination therapy for the treatment of chronic pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Retina. 2010;30:260–266. doi: 10.1097/iae.0b013e3181b8628e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.London N.J., Chiang A., Haller J.A. The dexamethasone drug delivery system: indications and evidence. Adv Ther. 2011;28:351–366. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0019-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams G.A., Haller J.A., Kuppermann B.D. Dexamethasone posterior-segment drug delivery system in the treatment of macular edema resulting from uveitis or Irvine-Gass syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]