Abstract

Na-K-ATPase, an integral membrane protein in mammalian cells, is responsible for maintaining the favorable intracellular Na gradient necessary to promote Na-coupled solute cotransport processes [e.g., Na-glucose cotransport (SGLT1)]. Inhibition of brush border membrane (BBM) SGLT1 is, at least in part, due to the diminished Na-K-ATPase in villus cells from chronically inflamed rabbit intestine. The aim of the present study was to determine the effect of Na-K-ATPase inhibition on the two major BBM Na absorptive pathways, specifically Na-glucose cotransport and Na/H exchange (NHE), in intestinal epithelial (IEC-18) cells. Na-K-ATPase was inhibited using 1 mM ouabain or siRNA for Na-K-ATPase-α1 in IEC-18 cells. SGLT1 activity was determined as 3-O-methyl-d-[3H]glucose uptake. Na-K-ATPase activity was measured as the amount of inorganic phosphate released. Treatment with ouabain resulted in SGLT1 inhibition at 1 h but stimulation at 24 h. To further characterize this unexpected stimulation of SGLT1, siRNA silencing was utilized to inhibit Na-K-ATPase-α1. SGLT1 activity was significantly upregulated by Na-K-ATPase silencing, while NHE3 activity remained unaltered. Kinetics showed that the mechanism of stimulation of SGLT1 activity was secondary to an increase in affinity of the cotransporter for glucose without a change in the number of cotransporters. Molecular studies demonstrated that the mechanism of stimulation was not secondary to altered BBM SGLT1 protein levels. Chronic and direct silencing of basolateral Na-K-ATPase uniquely regulates BBM Na absorptive pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. Specifically, while BBM NHE3 is unaffected, SGLT1 is stimulated secondary to enhanced affinity of the cotransporter.

Keywords: Na-K-ATPase, Na-glucose cotransporter, SGLT1, ouabain, intestinal inflammation

assimilation of most nutrients (e.g., glucose and amino acids), essential solutes (bile acid), certain nucleic acids (e.g., adenosine), and important vitamins (e.g., vitamin C) in human and other mammalian small intestine occur via Na-dependent cotransport processes on the brush border membrane (BBM) of enterocytes (19). All Na-dependent cotransport processes along the BBM of the enterocytes require a favorable transmembrane Na gradient. Basolateral membrane (BLM) Na-K-ATPase in intestinal epithelial cells is responsible for establishing and maintaining high intracellular K and low intracellular Na concentration (18). This favorable transmembrane Na gradient is, in turn, essential for proper BBM Na-coupled nutrient cotransporter function.

Na-K-ATPase is an integral transmembrane heterodimer protein in the BLM of mammalian epithelial cells. It is composed of equimolar amounts of α- and β-subunits: the α1-subunit is essential for Na-K-ATPase function, while the β1-subunit is important for stabilization of correct folding of the α1-polypeptide. The α-subunit mediates catalytic activity and contains intracellular binding sites for ATP and Na, a phosphorylation site, and extracellular binding sites for K. The glycosylated β-subunit is essential for Na-K-ATPase function, as it facilitates α/β-heterodimer formation and subsequent transport of the holoenzyme to the plasma membrane (15). The α1- and β1-subunits are constitutively expressed in the majority of tissues, whereas the α2-, α3-, and α4-subunits, as well as the β2- and β3-subunits, have limited expression (12). A third small polypeptide subunit, the γ-subunit, is found in association with α- and β-dimers; the γ-subunit does not seem to be required for Na-K-ATPase function and is suggested to play a regulatory role (24). The cytoplasmic domain of the α-subunit interacts with the NH2-terminal domain of ankyrin (10), a protein that connects Na-K-ATPase to the spectrin (fodrin)-based membrane skeleton and stabilizes Na-K-ATPase at the plasma membrane (20).

Proper Na-K-ATPase function is essential for maintenance of good nutritional health. Na-K-ATPase is also important for osmotic balance and volume regulation of cells (14). Dysfunction or deficiency of Na-K-ATPase has been identified in chronic neurodegenerative disorder and cardiovascular and renal diseases (5, 19, 27). Na-K-ATPase may be even more important in diarrheal diseases. It is the preservation of Na-K-ATPase-dependent Na-solute cotransport that is the basis for oral rehydration therapy (26). Several studies have described decreased Na-K-ATPase activity in acute and transient infectious enteritis (1, 8, 16, 22, 25). Furthermore, in chronic diarrheal diseases characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation resulting in malabsorption and, thus, malnutrition, alteration of Na-K-ATPase function may be very important. In an animal model resembling inflammatory bowel disease, it has been shown that Na-glucose (SGLT1), Na-alanine (ATB0), Na-glutamine (B0AT1), and Na-taurocholate (ASBT) cotransport are diminished in intact villus cells (21, 21a, 22, 23, 23a, 23b). In every instance, there is also a decrease in BLM Na-K-ATPase (6, 7, 21, 23). Thus it has been suggested that inhibition of Na and nutrient absorption in diarrheal diseases characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation is, at least in part, due to an alteration of Na-K-ATPase in the BLM of villus cells.

While overwhelming circumstantial evidence implicates a regulatory role for Na-K-ATPase on BBM Na absorptive pathways in pathophysiological conditions, how this ubiquitous enzyme may regulate BBM Na absorption in the normal intestine is less understood. Thus, in the present study, we determine the direct regulation of BBM primary Na absorptive pathways, specifically, Na/H exchange (NHE3) and SGLT1 by BLM Na-K-ATPase in enterocytes.

METHODS

Induction of chronic inflammation.

New Zealand White male rabbits (2.0–2.2 kg body wt) were used for the study. Experiments involving the use of animals in these studies were approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee (WVU ACUC). Chronic intestinal inflammation was induced in rabbits as previously reported (22). Briefly, pathogen-free rabbits were intragastrically inoculated with Eimeria magna oocytes to induce chronic intestinal inflammation, which manifested on days 13–14 postinoculation. Animals were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium through the ear vein on day 14 postinoculation.

Villus cell isolation.

Villus cells were isolated from normal and chronically inflamed rabbit small intestine by a Ca2+ chelation technique, as previously described (22). Briefly, a 3-ft section of ileum was filled and incubated at 37°C with buffer (0.15 mM EDTA, 112 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.4 mM K2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM l-glutamine, 0.5 mM β-hydroxybutyrate, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.4) for 3 min and gently palpated for another 3 min to facilitate cell dispersion. The buffer with the dispersed cells was drained from the ileal loop, and the suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min. The cells were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use.

Cell culture and ouabain treatment.

Rat small intestine (IEC-18) cells (American Type Culture Collection), between passages 5 and 30, were routinely maintained in the laboratory in DMEM [4.5 g/l glucose, 3.7 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% (vol/vol) bovine fetal serum, 100 U/l human insulin, 0.25 mM β-hydroxybutyric acid, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin] in a humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2 at 37°C. IEC-18 cells grown on 12-well plates were treated with ouabain (100 μM or 1 mM) or vehicle, and experiments were performed 1 or 24 h posttreatment. Experiments were conducted on postconfluence day 4.

RNA interference.

Silencer select predesigned negative control siRNA (catalog no. AM4611) and Na-K-ATPase siRNAs (catalog no. 4390771 and ID no. s127474) were used for siRNA transfections. The siRNAs (1.5 μg of each) were suspended in Nucleofector solution (pH 7.4, 7.1 mM ATP, 11.6 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 13.6 mM NaHCO3, 84 mM KH2PO4, and 2.1 mM glucose) and individually nucleofected into IEC-18 cells using a Nucleofector II device (Amaxa) according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Cells were plated in 12-well plates, and experiments were conducted on day 4 postconfluence.

Uptake studies in IEC-18 cells.

Uptake studies for SGLT1 were done using 3-O-methyl-d-[3H]glucose ([3H]3-OMG; GE Healthcare Biosciences) in IEC-18 cells from all experimental conditions. Cells were incubated with Leibovitz (L-15, 100% oxygen) medium (Invitrogen) containing supplements (as described above for DMEM) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were subsequently washed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature in a Na-free buffer (130 mM tetramethylammonium chloride, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM HEPES). Glucose uptake studies were then performed in cells incubated for 2 min with 130 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) with 10 μCi of 3H-OMG and 100 μM OMG in the presence or absence of 1 mM phlorizin and 10 mM d-glucose. The reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold Na-free buffer containing 25 mM d-glucose, and the cells were lysed in 800 μl of 1 N NaOH by incubation for 30 min at 70°C and mixed with 5 ml of Ecoscint A (National Diagnostics). The vials were kept in darkness for 24–48 h, and radioactivity retained by the cells was determined in a Beckman 6500 scintillation counter.

Na/H exchange activity was measured for all conditions in a similar fashion using 1 mM 22NaCl as substrate added to 130 mM tetramethylammonium in HEPES buffer, as described above. 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA)-sensitive Na/H exchange was measured by deducting the Na/H exchange activity in the presence of 50 μM EIPA (Sigma-Aldrich) from the total Na/H exchange activity of the IEC-18 cells. EIPA inhibits only NHE3, since this is added only to the BBM.

Na-K-ATPase enzyme activity measurement.

Na-K-ATPase was measured as inorganic phosphate (Pi) liberated by the method of Forbush (9) in cellular homogenates of normal and siRNA-transfected cells. The reaction was started by addition of 20 mM ATP-Tris to 20 μg of cellular homogenate in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.2) and 5 mM MgCl2 with 20 mM KCl and 100 mM NaCl. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 ml of ice-cold 2.8% ascorbic acid, 0.48% ammonium molybdate, and 2.8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-0.48 M HCl solution and placed on ice for 10 min. The color was developed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min after addition of 1.5 ml of 2% sodium citrate, 2% sodium arsenate, and 2% acetic acid. Readings were obtained at 705 nm, and K2HPO4 was used as Pi standard. Enzyme-specific activity was expressed as nanomoles of Pi released per milligram of protein per minute.

Protein determination.

Total protein was measured by the Lowry method using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Hercules, CA). BSA was used as a standard.

Intracellular Na determination.

Intracellular Na concentration was measured using cell-permeant Sodium Green tetraacetate salt (catalog no. S-6901, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, equal amounts of 1 × 106 cells/ml were plated on each well of 96-well plates and grown to day 4 postconfluence. To measure intracellular Na concentration, the cells were incubated for 1 h with 10 μM Sodium Green tetraacetate salt in Pluronic at room temperature. The FlexStation 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices) was used to read the resultant fluorescence at 532 nm. The intracellular concentration for different experimental conditions was determined by correlation of the fluorescence with a calibration response curve that was generated by loading normal IEC-18 cells for 1 h with 0–130 mM Na. Loading of free Na into the cells was accomplished with 5 μM gramicidin (catalog no. G-6888, Molecular Probes). The cells thus loaded with a known amount of sodium were incubated with 10 μM Sodium Green tetraacetate, and fluorescence emission was read at 532 nm. The resultant fluorescence values were used to calculate the dissociation constant of the indicator with the formula given by the manufacturer and was found to be close to that reported by Molecular Probes.

Isolation of total RNA and mRNA expression by RT-quantitative PCR.

For all conditions, total RNA was isolated from IEC-18 cells using RNeasy Plus total RNA purification mini kits (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The cDNAs synthesized were used as templates for RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-qPCR experiments for rat β-actin were performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (assay ID 4352931E, Applied Biosystems). RT-qPCR primers for rat SGLT1 were custom-synthesized using the oligonucleotide synthesis service provided by Applied Biosystems.

The primer and probe sequences for rat SGLT1 RT-qPCR are as follows: 5′-TTGTGGAGGACAGTGGTGAA-3′ (forward primer), 5′-AAAATAGGCGTGGCAGAAGA-3′ (reverse primer), and 5′FAM CATCAACGGCATCATCCTCCTGGTAMRA-3′ (TaqMan probe).

RT-qPCR for β-actin expression was run along with the SGLT1-specific RT-qPCR as an endogenous control under similar conditions to normalize expression levels of SGLT1 between individual samples. RT-qPCR analyses were performed in triplicate and repeated three times using RNA isolated from three sets of IEC-18 cells.

Western blot analysis.

Western blot experiments were performed according to standard protocols. For all conditions, IEC-18 cells were solubilized in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Igepal, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (SAFC Biosciences)] and separated on a 10% custom-prepared polyacrylamide gel. Separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF transfer membrane for SGLT1 Western blotting. SGLT1 was probed using a primary rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 603–623 of human SGLT1 (Abcam). Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used to detect SGLT1-bound primary antibody. ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) was used to detect the immobilized SGLT1 protein by chemiluminescence. The intensity of the bands was quantitated using a densitometric scanner (FluorChem, Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Data presentation.

For averaged data, means ± SE are shown, except when error bars are inclusive within the symbol. All uptake and RT-qPCR experiments were done in triplicate, unless otherwise specified. The number (n) for any set of experiments refers to uptake experiments, total RNA, or protein extracts from different sets of cells. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Effect of Na-K-ATPase activity on chronically inflamed rabbit cells.

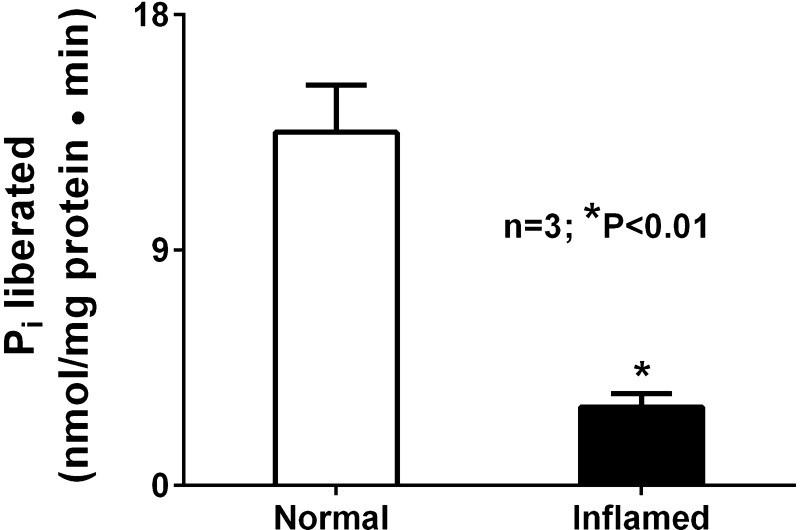

Na-K-ATPase activity was significantly decreased in villus cell homogenate obtained from chronically inflamed rabbit intestine compared with that obtained from normal intestine (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of chronic intestinal inflammation on Na-K-ATPase activity. Na-K-ATPase activity was significantly inhibited in villus cell homogenates from chronically inflamed intestine compared with control.

Effect of ouabain on SGLT1 in IEC-18 cells.

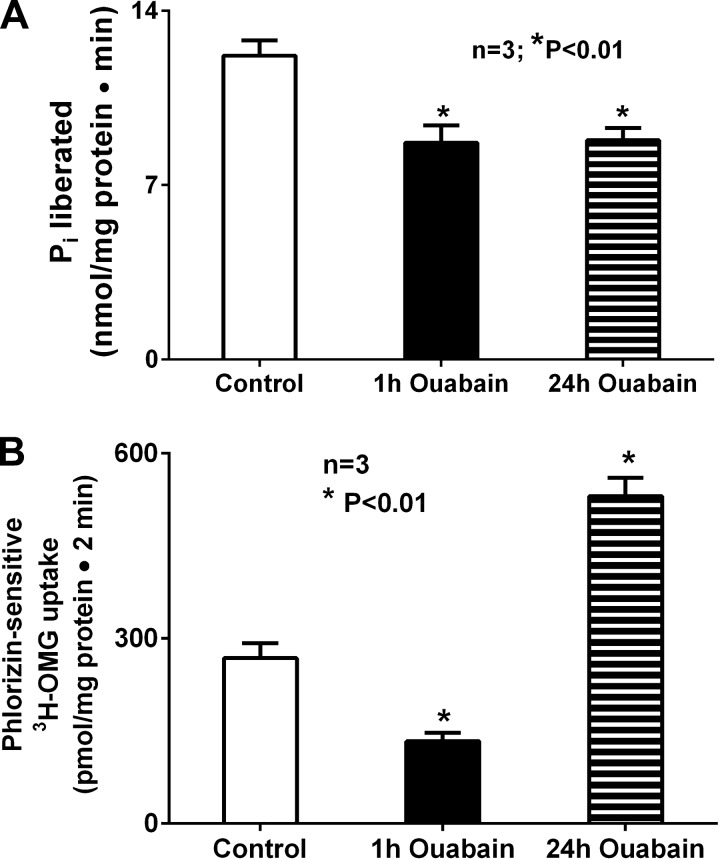

In the chronically inflamed small intestine, innumerable immune inflammatory mediators that are known to be elevated in the mucosa may affect Na-K-ATPase and/or its dependent BBM cotransport processes. To more directly study the effect of inhibition of Na-K-ATPase on BBM SGLT1 (also known to be inhibited in the chronically inflamed small intestine), Na-K-ATPase was inhibited in vitro in IEC-18 cells with ouabain. After 1 h of treatment, ouabain inhibited Na-K-ATPase activity (Fig. 2A; 12.2 ± 0.6 and 8.7 ± 0.7 nmol Pi·mg protein−1·min−1 in control and ouabain-treated cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.01). BBM SGLT1 was also inhibited in these cells (Fig. 2B; 268.3 ± 24.04 and 133.0 ± 14.98 pmol·mg protein−1·2 min−1 in control and ouabain-treated cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.01). However, the effects of immune inflammatory mediators on Na-K-ATPase in the chronically inflamed intestine were not acute, but chronic. So IEC-18 cells were treated for 24 h with ouabain. Chronic exposure to ouabain continued to inhibit Na-K-ATPase activity in IEC-18 cells (Fig. 2A; 11.8 ± 0.3 and 8.8 ± 0.5 nmol Pi·mg protein−1·min−1 in control 24-h ouabain-treated cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.01). Interestingly, unlike acute exposure, chronic exposure to ouabain caused a significant increase in BBM SGLT1 activity (Fig. 2B; 268.3 ± 24.04 and 530.0 ± 30.20 pmol·mg protein−1·2 min−1 in control and 24-h ouabain-treated cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.005).

Fig. 2.

A: effect of ouabain on Na-K-ATPase activity in IEC-18 cells. Treatment of IEC-18 cells for 1 h with 1 mM ouabain significantly inhibited Na-K-ATPase activity compared with control. This inhibitory effect was sustained when cells were treated with ouabain for 24 h. B: effect of ouabain on phlorizin-sensitive 3-O-methyl-d-[3H]glucose ([3H]OMG) uptake in IEC-18 cells. Phlorizin-sensitive [3H]OMG uptake was significantly inhibited in cells treated with ouabain for 1 h, but 24 h of the same treatment resulted in significant stimulation of [3H]OMG uptake compared with control.

Effect of Na-K-ATPase silencing in IEC-18 cells.

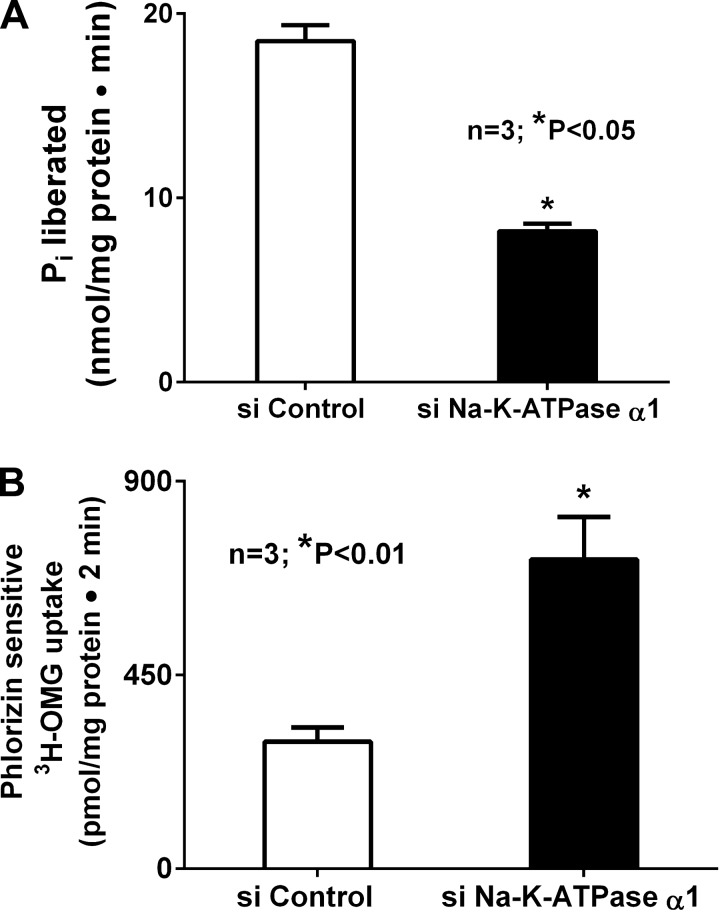

To further and more specifically explain the unique phenomenon of SGLT1 stimulation when Na-K-ATPase was inhibited chronically with ouabain, we employed Na-K-ATPase silencing to inhibit Na-K-ATPase-α1. This resulted in significant inhibition of Na-K-ATPase activity in cells transfected with siRNA for Na-K-ATPase (Fig. 3A; 18.5 ± 0.9 and 8.2 ± 0.1 nmol Pi·mg protein−1·min−1 in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells, respectively, n = 5, P < 0.05). In these chronically and specifically Na-K-ATPase-inhibited cells, we then studied Na-dependent glucose uptake. In siNa-K-ATPase-silenced cells, SGLT1 was significantly stimulated (Fig. 3B; 294.9 ± 33.4 and 718.1 ± 96.6 pmol·mg protein−1·2 min−1 in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.05). These data indicate that chronic inhibition of BLM Na-K-ATPase results in stimulation of BBM SGLT1.

Fig. 3.

A: effect of chronic inhibition of Na-K-ATPase in IEC-18 cells. Transfection with siRNA for Na-K-ATPase-α1 (siNa-K-ATPase-α1) significantly inhibited Na-K-ATPase activity, as expected, compared with control. B: effect of siNa-K-ATPase-α1 on phlorizin-sensitive [3H]OMG uptake. Chronic inhibition of Na-K-ATPase via siNa-K-ATPase-α1 transfection resulted in significant stimulation of phlorizin-sensitive [3H]OMG uptake.

Effect of siNa-K-ATPase-α1 silencing on NHE3 activity in IEC-18 cells.

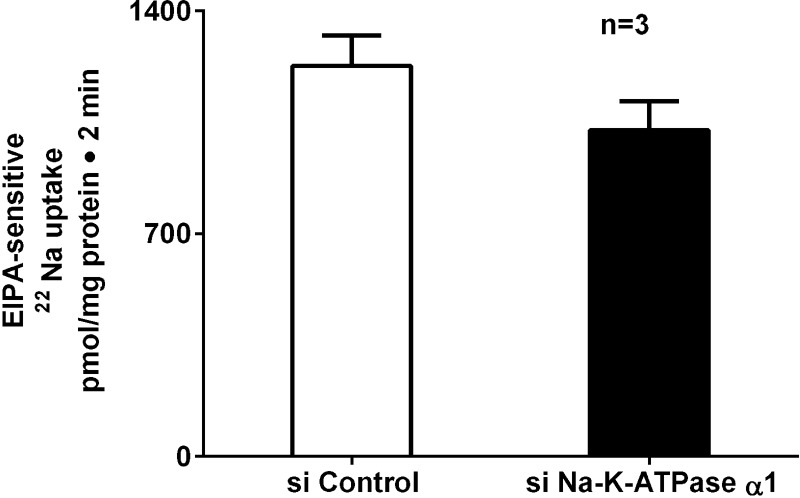

The other major Na absorptive pathway in intestinal epithelial cells is NHE3. Since specific silencing of Na-K-ATPase upregulated SGLT1 activity, we next determined the effect of specific silencing of Na-K-ATPase on NHE3 activity. NHE3 activity was measured as EIPA-sensitive Na uptake. Unlike SGLT1, NHE3 activity was unaltered with siNa-K-ATPase silencing (Fig. 4; 1,228 ± 95 and 1,026 ± 91 pmol·mg protein−1·2 min−1 in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells, respectively, n = 3). These data indicate that the effect of Na-K-ATPase silencing is specific to BBM SGLT1, but not NHE3.

Fig. 4.

Effect of siNa-K-ATPase-α1 on EIPA-sensitive 22Na uptake in IEC-18 cells. Chronic inhibition of Na-K-ATPase with its specific siRNA did not have an effect on EIPA-sensitive 22Na uptake in IEC-18 cells.

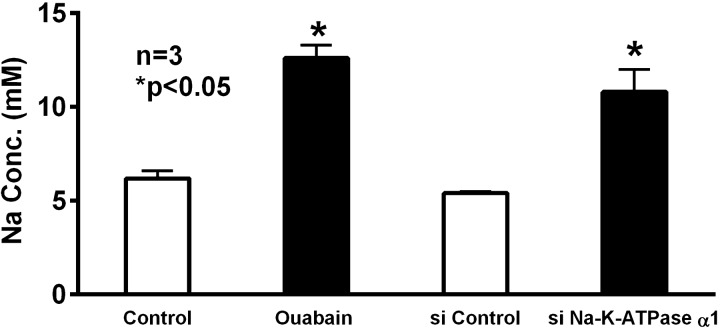

Intracellular Na levels in IEC-18 cells.

To determine whether intracellular Na levels were affected when Na-K-ATPase was chronically inhibited by ouabain or transfection with siRNA for Na-K-ATPase-α1, we measured intracellular Na levels. Compared with control, intracellular Na was increased in IEC-18 cells treated with ouabain (Fig. 5; 6.2 ± 0.4 and 12.6 ± 0.7 mM in control and ouabain-treated cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.05). Similarly, in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced cells, intracellular Na levels were significantly increased (Fig. 5; 5.4 ± 0.1 and 10.8 ± 1.2 mM in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1-transfected cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.05). These data indicate that chronic inhibition of Na-K-ATPase results in increased intracellular Na and, thus, a diminished transmembrane Na gradient, which would likely affect Na-solute cotransporters on the BBM.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Na-K-ATPase inhibition on intracellular Na concentration in IEC-18 cells. Intracellular Na concentration was significantly increased in ouabain-treated cells and cells transfected with siRNA for Na-K-ATPase-α1 compared with their respective controls.

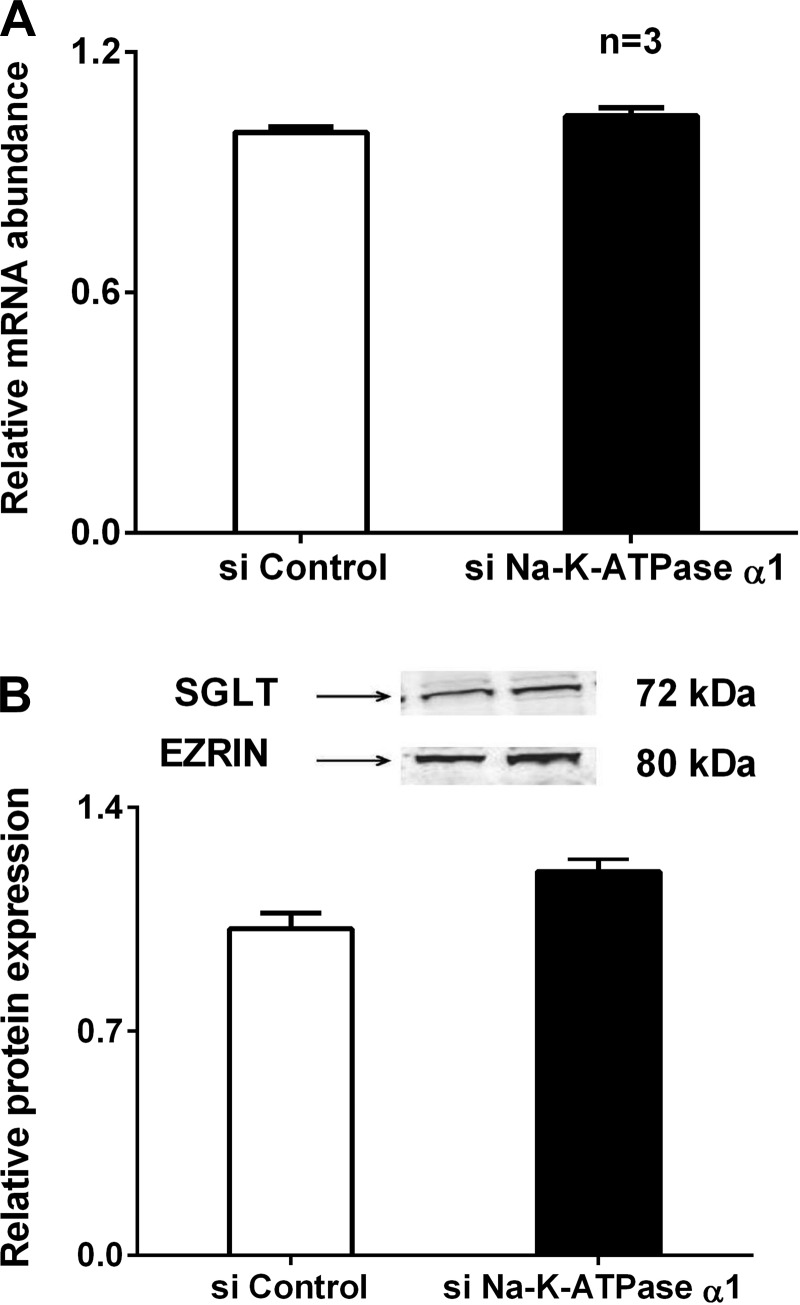

Effect of Na-K-ATPase-α1 silencing on SGLT1 mRNA and protein expression in IEC-18 cells.

To determine the molecular mechanism of stimulation of SGLT1 by siNa-K-ATPase-α1 silencing in IEC-18 cells, mRNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. Transfection of IEC-18 cells with Na-K-ATPase-α1 siRNA did not alter SGLT1 mRNA levels in these cells (Fig. 6A). Since mRNA levels do not necessarily correlate with functional protein levels on the BBM, Western blot studies were performed to further characterize the molecular mechanism of SGLT1 regulation by Na-K-ATPase-α1 silencing. In IEC-18 cells silenced with siNa-K-ATPase-α1, SGLT1 protein levels were not significantly altered (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that the mechanism of SGLT1 stimulation is likely not transcriptional.

Fig. 6.

A: effect of siNa-K-ATPase-α1 on Na-glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) mRNA. There was no significant alteration of SGLT1 mRNA expression in siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells compared with control. B: effect of siNa-K-ATPase-α1 on BBM SGLT1 protein expression. Top: representative blot of BBM SGLT1 with ezrin as loading control. Bottom: densitometric analysis of BBM SGLT1 protein expression showed no significant alteration in siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells compared with control.

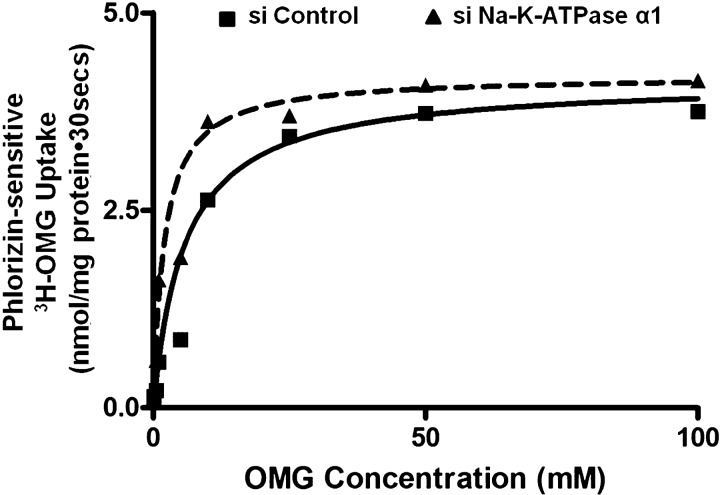

Kinetic parameters for SGLT1 activity in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced IEC-18 cells.

To further determine the mechanism of SGLT1 stimulation by siNa-K-ATPase-α1 silencing, kinetic studies were performed. Na-dependent glucose uptake was measured as a function of varying concentrations of glucose at 30 s in IEC-18 cells. As the extracellular concentration of glucose was increased, Na-glucose uptake was stimulated and, subsequently, became saturated in all conditions. Kinetic parameters were derived from the uptake data using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). In siNa-K-ATPase-silenced cells, the maximal rate of glucose uptake (Vmax) was not altered (4.1 ± 0.7 and 4.2 ± 0.8 nmol·mg protein−1·30 s−1 in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells, respectively, n = 3). However, the affinity (1/Km) of the cotransporter for glucose increased significantly (5.8 ± 0.4 and 2.15 ± 0.3 mM in control and siNa-K-ATPase-α1 cells, respectively, n = 3, P < 0.01). These data, in conjunction with the molecular studies described above, indicate that the mechanistic basis for stimulation of SGLT1 activity in Na-K-ATPase-silenced cells is secondary to an increase in affinity of the cotransporter for glucose without a change in the number of cotransporters (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Kinetic parameters for SGLT1 activity in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced IEC-18 cells. Na-dependent glucose ([3H]OMG) uptake is shown as a function of 0–100 mM extravesicular glucose (OMG). Uptake for all concentrations was determined at 30 s. As the concentration of extravesicular glucose was increased, uptake of glucose was stimulated and, subsequently, became saturated in IEC-18 cells in all conditions. Affinity (1/Km) for glucose uptake significantly increased in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-transfected IEC-18 cells compared with control. Data represent average of 3 experiments; each experiment was done in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

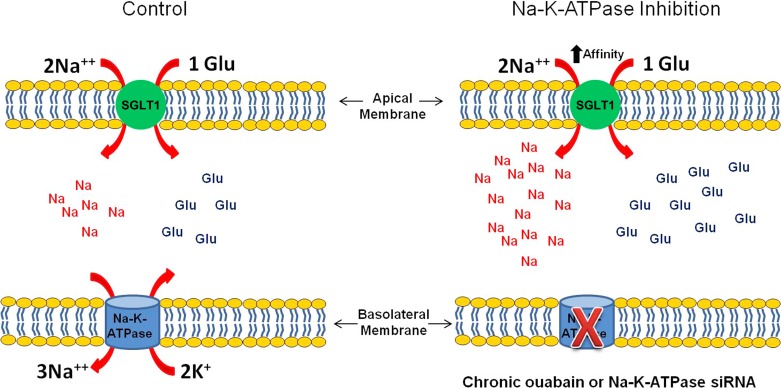

The importance of Na-K-ATPase as a driver of Na-dependent solute absorption in the mammalian small intestine is fairly well established. In an animal model of human inflammatory bowel disease, our laboratory has demonstrated the inhibition of a variety of Na-dependent glucose, amino acid, bile acid, and nucleic acid cotransporters. At the villus cell level, since BLM Na-K-ATPase was inhibited, it was hypothesized that at least part of the inhibition of these Na-solute cotransport processes was secondary to Na-K-ATPase inhibition. However, a variety of immune inflammatory mediators are elevated in the chronically inflamed intestine, and any of these immune inflammatory mediators can affect the BBM Na-solute cotransporters, as well as BLM Na-K-ATPase. We previously demonstrated that when these immune inflammatory pathways were inhibited, the inhibition of BBM Na-solute cotransport and BLM Na-K-ATPase was reversed (3, 6, 23). Therefore, to more specifically determine the effect of Na-K-ATPase inhibition on the BBM Na-solute cotransport process in the absence of confounding variables, we studied Na-K-ATPase inhibition in an in vitro model of intestinal epithelial cells. Figure 8 summarizes SGLT1 activity in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced and chronic ouabain-treated IEC-18 cells. Not unexpectedly, acute inhibition of Na-K-ATPase with ouabain inhibited BBM Na-glucose cotransport. However, the intestinal pathophysiology we studied is a chronic condition. Thus we looked at the long-term inhibition of Na-K-ATPase. We were surprised to find that long-term inhibition of Na-K-ATPase resulted in stimulation of BBM Na-glucose cotransport. It is conceivable that this is a compensatory mechanism employed by the cell for the diminished transmembrane Na gradient. However, this effect was specific to SGLT1, but not the other primary Na absorptive pathway, Na/H exchange, in intestinal epithelial cells. On the basis of thermodynamics, the diminished transcellular Na gradient may be expected to decrease Na influx via NHE3, but this exchanger was not altered. It is conceivable that the elevation of intracellular Na was not adequate to affect NHE3. Nevertheless, this novel observation is suggestive of the molecular mechanism of stimulation of SGLT1 when Na-K-ATPase was inhibited. First, to avoid any untoward effect of chronic exposure to ouabain, siRNA for the α1-subunit was utilized to inhibit Na-K-ATPase. As expected, transfection with this siRNA diminished Na-K-ATPase activity. However, in these cells, SGLT1 was stimulated, but Na/H was unaffected. The mechanism of SGLT1 stimulation was secondary to an increase in the affinity of the cotransporter for glucose without a change in the number of cotransporters. Alterations in cotransporter affinity are posttranscriptional and likely at the level of phosphorylation and/or glycosylation. For example, it has been shown that glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3β) stimulates glucose-induced current when SGLT1 and GSK3β are expressed in Xenopus oocytes (17). In contrast, a decrease in glycosylation of SGLT1 has been shown to inhibit SGLT1 activity (2). The precise mechanism of alteration of Km of SGLT1 in Na-K-ATPase-inhibited cells and the intracellular pathways involved will need to be elucidated in future studies. The fact that intracellular Na is increased in ouabain-treated and siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced cells would suggest that salt-inducible kinase may have a role in the posttranslational modification of SGLT1 in these cells. It is conceivable that Na-K-ATPase may regulate a BBM transporter by a means other than simply altering intracellular Na. For example, in a renal-derived epithelial cell line (LLC-PK1), chronic exposure to ouabain, but at a concentration too low to inhibit Na-K-ATPase-mediated transport or to raise intracellular Na, was shown to affect the function and expression of the epithelial BBM NHE3 (11, 13).

Fig. 8.

SGLT1 activity in siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced IEC-18 cells. Accumulation of Na increased in chronic ouabain-treated and siNa-K-ATPase-α1-silenced IEC-18 cells. Increase in Na concentration was secondary to increase in affinity of SGLT1.

As previously noted, Na-K-ATPase activity is diminished in villus cells from the chronically inflamed intestine. In these cells, however, SGLT1 is inhibited, not stimulated, as is the case when the enzyme is directly inhibited chemically or with siRNA in this study. Furthermore, the mechanism of resultant alteration of SGLT1 is uniquely different in each case. Inhibition of SGLT1 in chronically inflamed intestine is secondary to a decrease in the de novo synthesis of SGLT1 protein, whereas stimulation of SGLT1 in ouabain-treated or siRNA-transfected cells is posttranslational and secondary to altered affinity of the cotransporter for glucose. Possible explanations for these observations include the fact that, in the chronically inflamed intestine, numerous immune inflammatory mediators are upregulated, and this may have an independent effect on SGLT1 beyond any effect of diminished Na-K-ATPase. In fact, immune inflammatory mediators causing inhibition of SGLT1 have been reported. For example, tumor necrosis factor-α has been shown to downregulate SGLT1 in human colon cancer cells (4). Alternatively, the mechanism of Na-K-ATPase inhibition in the chronically inflamed intestine may be fundamentally different from that achieved by ouabain or siRNA for the α1-subunit. In the latter instance, there is a decrease in the otherwise functional Na-K-ATPase in the BLM; in the former instance, the enzyme may be fundamentally altered by yet to be determined immune inflammatory mediators.

In conclusion, chronic and specific inhibition of BLM Na-K-ATPase in intestinal epithelial cells increases intracellular Na. It also stimulates influx of glucose via BBM SGLT1, but not influx of Na via NHE3. The mechanism of stimulation of SGLT1 is secondary to an increase in the affinity of the cotransporter for glucose. Thus, Na-K-ATPase uniquely regulates BBM SGLT1, possibly in a compensatory fashion for the loss of transmembrane Na resulting from its inhibition.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-45062 and DK-58034 to U. Sundaram.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.M. and S.G. performed the experiments; P.M. analyzed the data; P.M., S.G., S.A., B.P., and S.S. prepared the figures; P.M., S.G., S.A., B.P., S.S., and U.S. drafted the manuscript; S.A., B.P., S.S., and U.S. edited and revised the manuscript; G.M.D. and U.S. interpreted the results of the experiments; G.M.D. and U.S. approved the final version of the manuscript; U.S. developed the concept and designed the research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgayer H, Kruis W, Paumgartner G, Wiebecke B, Brown L, Erdmann E. Inverse relationship between colonic (Na+ + K+)-ATPase activity and degree of mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 33: 417–422, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur S, Coon S, Kekuda R, Sundaram U. Regulation of sodium glucose co-transporter SGLT1 through altered glycosylation in the intestinal epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1838: 1208–1214, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur S, Saha P, Sundaram S, Kekuda R, Sundaram U. Regulation of sodium-glutamine cotransport in villus and crypt cells by glucocorticoids during chronic enteritis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18: 2149–2157, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrenetxe J, Sanchez O, Barber A, Gascon S, Rodriguez-Yoldi MJ, Lostao MP. TNFα regulates sugar transporters in the human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2. Cytokine 64: 181–187, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauhan NB, Lee JM, Siegel GJ. Na,K-ATPase mRNA levels and plaque load in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Neurosci 9: 151–166, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coon S, Kekuda R, Saha P, Sundaram U. Glucocorticoids differentially regulate Na-bile acid cotransport in normal and chronically inflamed rabbit ileal villus cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G675–G682, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coon S, Kekuda R, Saha P, Sundaram U. Reciprocal regulation of the primary sodium absorptive pathways in rat intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C496–C505, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ejderhamn J, Finkel Y, Strandvik B. Na,K-ATPase activity in rectal mucosa of children with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 24: 1121–1125, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbush B., 3rd Assay of Na,K-ATPase in plasma membrane preparations: increasing the permeability of membrane vesicles using sodium dodecyl sulfate buffered with bovine serum albumin. Anal Biochem 128: 159–163, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan C, Puschel B, Koob R, Drenckhahn D. Identification of a binding motif for ankyrin on the α-subunit of Na+,K+-ATPase. J Biol Chem 270: 29971–29975, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaunitz JD. Membrane transport proteins: not just for transport anymore. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F995–F996, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingrel JB, Orlowski J, Shull MM, Price EM. Molecular genetics of Na,K-ATPase. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 38: 37–89, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oweis S, Wu L, Kiela PR, Zhao H, Malhotra D, Ghishan FK, Xie Z, Shapiro JI, Liu J. Cardiac glycoside downregulates NHE3 activity and expression in LLC-PK1 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F997–F1008, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlov KV, Sokolov VS. Electrogenic ion transport by Na+,K+-ATPase. Membr Cell Biol 13: 745–788, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pressley TA, Allen JC, Clarke CH, Odebunmi T, Higham SC. Amino-terminal processing of the catalytic subunit from Na+-K+-ATPase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C825–C832, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachmilewitz D, Karmeli F, Sharon P. Decreased colonic Na-K-ATPase activity in active ulcerative colitis. Isr J Med Sci 20: 681–684, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rexhepaj R, Dermaku-Sopjani M, Gehring EM, Sopjani M, Kempe DS, Foller M, Lang F. Stimulation of electrogenic glucose transport by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Cell Physiol Biochem 26: 641–646, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson JD, Flashner MS. The (Na+ + K+)-activated ATPase. Enzymatic and transport properties. Biochim Biophys Acta 549: 145–176, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose AM, Valdes R Jr. Understanding the sodium pump and its relevance to disease. Clin Chem 40: 1674–1685, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubtsov AM, Lopina OD. Ankyrins. FEBS Lett 482: 1–5, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saha P, Arthur S, Kekuda R, Sundaram U. Na-glutamine co-transporters B(0)AT1 in villus and SN2 in crypts are differentially altered in chronically inflamed rabbit intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818: 434–442, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Sundaram U, Coon S, Wisel S, West AB. Corticosteroids reverse the inhibition of Na-glucose cotransport in the chronically inflamed rabbit ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G211–G218, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundaram U, West AB. Effect of chronic inflammation on electrolyte transport in rabbit ileal villus and crypt cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 272: G732–G741, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundaram U, Wisel S, Coon S. Neutral Na-amino acid cotransport is differentially regulated by glucocorticoids in the normal and chronically inflamed rabbit small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G467–G474, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Sundaram U, Wisel S, Stengelin S, Kramer W, Rajendran V. Mechanism of Na+-bile cotransport during chronic ileal inflammation in rabbits. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G1259–G1265, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23b.Sundaram U, Wisel S, Fromkes JJ. Unique mechanism of inhibition of Na+-amino acid cotransport during chronic ileal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G483–G489, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Therien AG, Blostein R. Mechanisms of sodium pump regulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C541–C566, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tripp JH, Muller DP, Harries JT. Mucosal (Na+-K+)-ATPase and adenylate cyclase activities in children with toddler diarrhea and the postenteritis syndrome. Pediatr Res 14: 1382–1386, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright EM, Hirayama BA, Loo DF. Active sugar transport in health and disease. J Intern Med 261: 32–43, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegelhoffer A, Kjeldsen K, Bundgaard H, Breier A, Vrbjar N, Dzurba A. Na,K-ATPase in the myocardium: molecular principles, functional and clinical aspects. Gen Physiol Biophys 19: 9–47, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]