Abstract

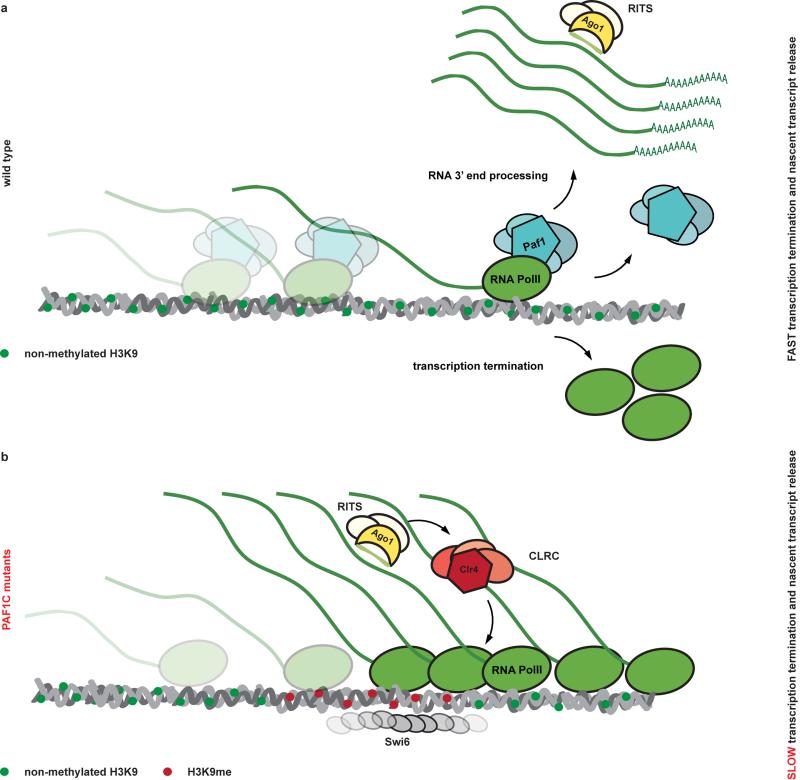

RNA interference (RNAi) refers to the ability of exogenously introduced double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to silence expression of homologous sequences. Silencing is initiated when the enzyme Dicer processes the dsRNA into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Small RNA molecules are incorporated into Argonaute protein-containing effector complexes, which they guide to complementary targets to mediate different types of gene silencing, specifically post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) and chromatin-dependent gene silencing1. Although endogenous small RNAs play critical roles in chromatin-mediated processes across kingdoms, efforts to initiate chromatin modifications in trans by using siRNAs have been inherently difficult to achieve in all eukaryotic cells. Using fission yeast, we show that RNAi-directed heterochromatin formation is negatively controlled by the highly conserved RNA polymerase-associated factor 1 complex (Paf1C). Temporary expression of a synthetic hairpin RNA in Paf1C mutants triggers stable heterochromatin formation at homologous loci, effectively silencing genes in trans. This repressed state is propagated across generations by continual production of secondary siRNAs, independently of the synthetic hairpin RNA. Our data support a model where Paf1C prevents targeting of nascent transcripts by the siRNA-containing RNA-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) complex and thereby epigenetic gene silencing, by promoting efficient transcription termination and rapid release of the RNA from the site of transcription. We show that although compromised transcription termination is sufficient to initiate the formation of bi-stable heterochromatin by trans-acting siRNAs, impairment of both transcription termination and nascent transcript release is imperative to confer stability to the repressed state. Our work uncovers a novel mechanism for small RNA- mediated epigenome regulation and highlights fundamental roles for Paf1C and the RNAi machinery in building epigenetic memory.

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a functional RNAi pathway is required for the formation and stable propagation of constitutive heterochromatin found at pericentromeric repeat sequences. S. pombe contains single genes encoding for an Argonaute and a Dicer protein, called ago1+ and dcr1+ respectively. Centromeres of ago1Δ or dcr1Δ cells have markedly reduced histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation, which is a hallmark of heterochromatin, and defective chromosome segregation and heterochromatic gene silencing2. Ago1 is loaded with endogenous small RNAs corresponding to heterochromatic repeats, and interacts with Chp1 and Tas3 to form the RITS complex3. Current models propose that Ago1-bound small RNAs target RITS to centromeres via base-paring interactions with nascent, chromatin-associated non-coding transcripts. Consequently, RITS recruits the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex (RDRC) to initiate dsRNA synthesis and siRNA amplification, as well as the cryptic loci regulator complex (CLRC) to facilitate methylation of histone H3K94. Chp1 reinforces the heterochromatin association of RITS by binding methylated H3K9 with high affinity5, thereby creating a positive-feedback loop between siRNA biogenesis, RITS localization, and H3K9 methylation. Hence, siRNA-programmed RITS acts as a specificity determinant for the recruitment of other RNAi complexes and chromatin-modifying enzymes to centromeres. However, an outstanding question is whether synthetic siRNAs can also function in this context, and thereby be used to trigger de novo formation of heterochromatin, particularly outside of centromeric repeats, in order to stably silence gene expression at will1.

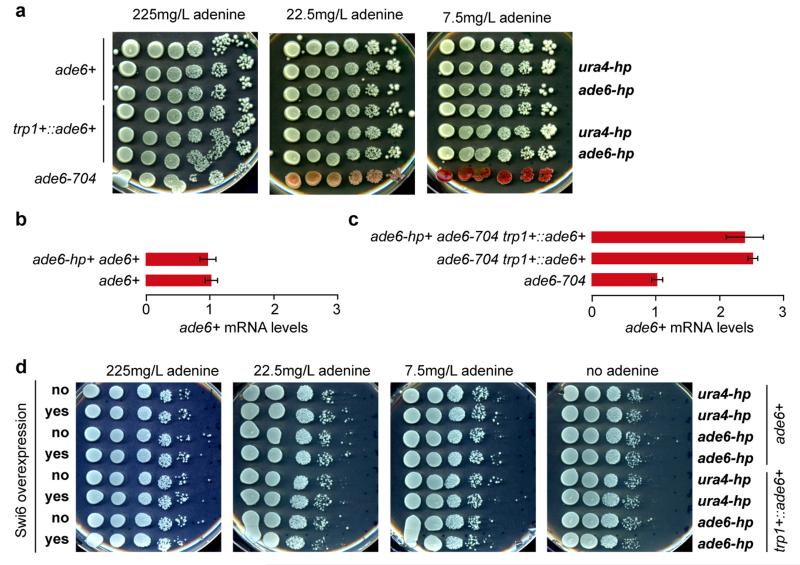

Small RNAs play critical roles in endogenous chromatin-mediated processes also in plants, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and ciliates. Their role in chromatin silencing can also be extended to mammalian cells, although the mechanisms and physiological pathways are less clear1,6. Yet, efforts to initiate chromatin modifications in trans by using siRNAs have been inherently difficult to achieve in all organisms. In plants, this is because the ability of siRNAs to induce DNA methylation at gene promoters is context-dependent and sensitive to pre-existing chromatin modifications7. And although siRNAs have been shown to promote DNA methylation in trans on homologous reporter transgenes in Tobacco and Arabidopsis8, it is unclear whether this is a general phenomenon for endogenous promoters. In mammalian cells, the introduction of siRNAs or hairpin RNAs has been reported to promote the modification of DNA and histones9-11. However, most small RNAs seem to exclusively mediate PTGS, and siRNA-mediated silencing of transcription does not necessarily require chromatin modification12,13. Consequently, the potential of synthetic siRNAs to trigger long-lasting gene repression in mammalian cells is debated. Similarly, although studies in S. pombe have shown that RNA hairpin-derived siRNAs can promote H3K9 methylation in trans at a small number of loci14,15, it is inefficient, locus-dependent, and the silent state observed is weak and highly unstable14. Rather, endogenous protein-coding genes appear to be refractory to siRNA-directed repression in trans in wild type cells (Extended Data Fig. 1 and 2). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the ability of siRNAs to direct de novo formation of heterochromatin in trans is under strict control by mechanisms that have thus far remained elusive.

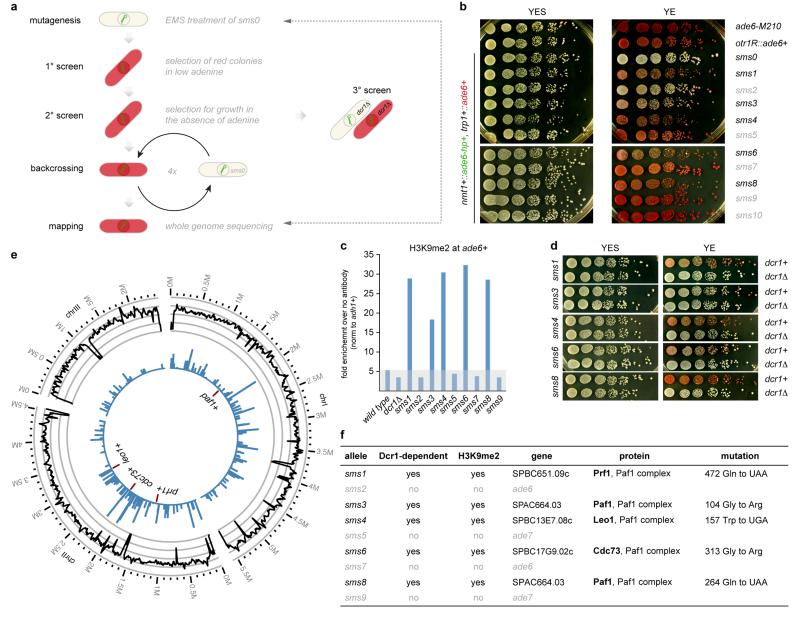

To identify putative suppressors of siRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation we designed a small RNA-mediated silencing (sms) forward genetic screen. We constructed a reporter strain (sms0), which expresses an RNA hairpin (ade6-hp) that is complementary to 250nt of ade6+ (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1). We chose ade6+ as a reporter because ade6 mutant cells form red colonies on limiting adenine indicator plates, whereas ade6+ cells appear white. Although the ade6-hp construct generated siRNAs complementary to ade6+ mRNAs, no red colonies were visible, demonstrating that ade6+ siRNAs cannot silence the ade6+ gene in trans in sms0 cells (Extended Data Fig. 1b and 2). To screen for mutants that would enable ade6+ siRNAs to act in trans, we mutagenized sms0 cells with ethylmethansulfonate (EMS). This revealed five sms mutants that are highly susceptible to de novo formation of heterochromatin and stable gene silencing by siRNAs that are acting in trans (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Information).

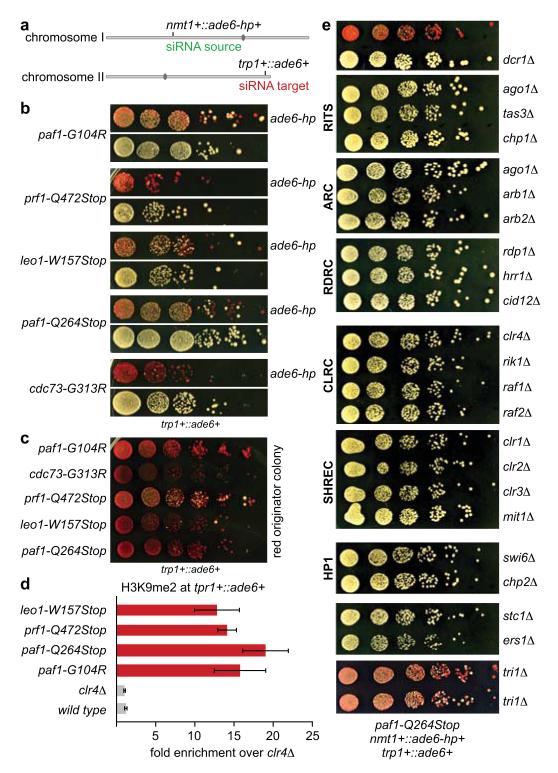

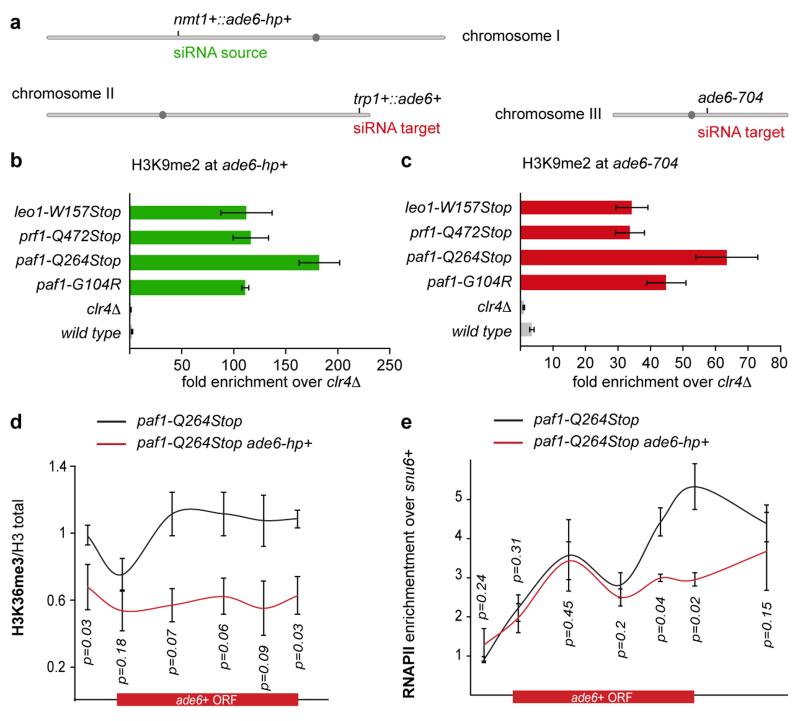

Figure 1. siRNA-directed de novo formation of heterochromatin.

a, ade6-hp RNA producing locus and siRNA target in trans in the sms0 strain. b, Silencing assay performed with freshly generated Paf1C mutants. c, Silencing assay performed with red colonies from b. d, ade6+ siRNAs direct the methylation of H3K9 in trans at the trp1+::ade6+ locus in Paf1C mutant cells. Error bars, SEM; n=3 technical replicates. e, Gene silencing at the trp1+::ade6+ locus depends on the same factors as constitutive heterochromatin at centromeric repeats.

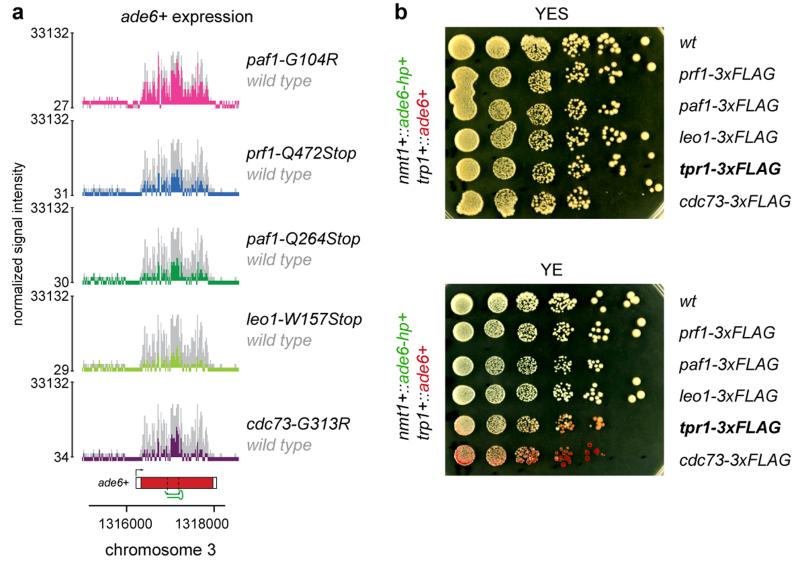

To map the mutations in sms mutants we re-sequenced the genomes of sms0 and backcrossed sms mutants using whole-genome next generation sequencing (Supplementary Information). We mapped missense or nonsense mutations in the genes SPBC651.09c, SPAC664.03, SPBC13E7.08c, and SPBC17G9.02c (Extended Data Fig. 3), whose homologues in budding yeast encode for protein subunits of the Paf1 complex. We therefore named SPAC664.03, SPBC13E7.08c, and SPBC17G9.02c after the S. cerevisiae homologues paf1+, leo1+, and cdc73+, respectively. SPBC651.09c has already been named as prf1+16. To validate these as the causative mutations, we reconstituted the candidate point mutations in Paf1, Leo1, Cdc73, and Prf1 in sms0 cells. All five point mutations recapitulated the sms mutant phenotype in cells expressing ade6-hp siRNAs (Fig. 1b, c). As expected from the red color assays, ade6+ mRNA levels were reduced in all mutant strains. siRNA-mediated ade6+ silencing was also observed in cells that express a C-terminally 3xFLAG tagged version of the fifth Paf1C subunit Tpr1, which acts as a hypomorphic allele (Extended Data Fig. 4). Therefore, we have identified mutant alleles for the homologs of all five subunits of Paf1C that enable siRNAs to induce gene silencing in trans.

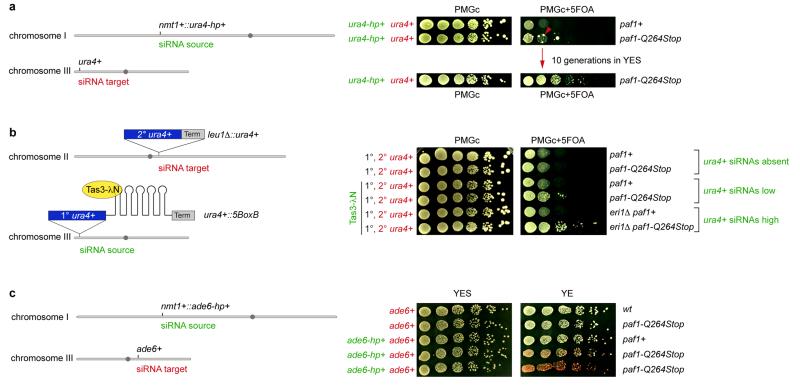

We next analyzed whether other genes could also be silenced in trans in the Paf1C mutants. We first selected the endogenous ura4+ gene, as this has been shown to be refractory to silencing by siRNAs acting in trans14,15,17. The paf1-Q264Stop mutation was introduced in a strain expressing ura4+ siRNAs from a ura4+ hairpin integrated at the nmt1+ locus15. ura4+ repression was monitored by growing cells on media containing 5-Fluoroorotic Acid (5-FOA), which is toxic to ura4+ expressing cells. As expected, paf1+ cells did not grow on 5-FOA containing media, indicating that the ura4+ gene is expressed. However, paf1-Q264Stop cells formed colonies on 5-FOA containing media, demonstrating siRNA-directed silencing of the endogenous ura4+ locus (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Similarly, siRNAs generated at the heterochromatic ura4+::5BoxB locus18 were able to silence a leu1Δ::ura4+ reporter in trans in paf1-Q264Stop but not paf1+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b), demonstrating that siRNAs generated from sources other than RNA stem-loop structures also direct trans-silencing in paf1+ mutant cells. Finally, we also observed silencing of the endogenous ade6+ gene when ade6-hp siRNAs were expressed from the nmt1+ locus in paf1-Q264Stop cells (Extended Data Fig. 5c). In summary, Paf1C mutations enabled siRNA-directed silencing in trans at all euchromatic loci that we tested. The foregoing results indicated that de novo formation of heterochromatin was mediated by trans-acting siRNAs. Indeed, Paf1C mutants showed high H3K9 methylation at all ade6+ siRNA target loci (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 6a-c), demonstrating that Paf1C prevents trans- as well as cis-acting siRNAs from directing methylation of H3K9. Further corroborating the formation of bona fide heterochromatin at the ade6+ target locus, ade6+ repression was dependent on components of SHREC (histone deacetylase complex) and CLRC (histone methyltransferase complex), as well as the HP1 proteins Swi6 and Chp2, which are known to facilitate constitutive heterochromatin formation at centromeres (Fig. 1e). Finally, formation of heterochromatin reduced transcriptional activity of the ade6+ gene as evidenced by reduced H3K36 tri-methylation and RNA polymerase II occupancy (Extended Data Fig. 6d, e). From these results we conclude that siRNAs can initiate the formation of heterochromatin and gene silencing, but that this is under strict negative control by Paf1C. This explains previous unsuccessful attempts to induce stable heterochromatin formation in trans using synthetic siRNAs.

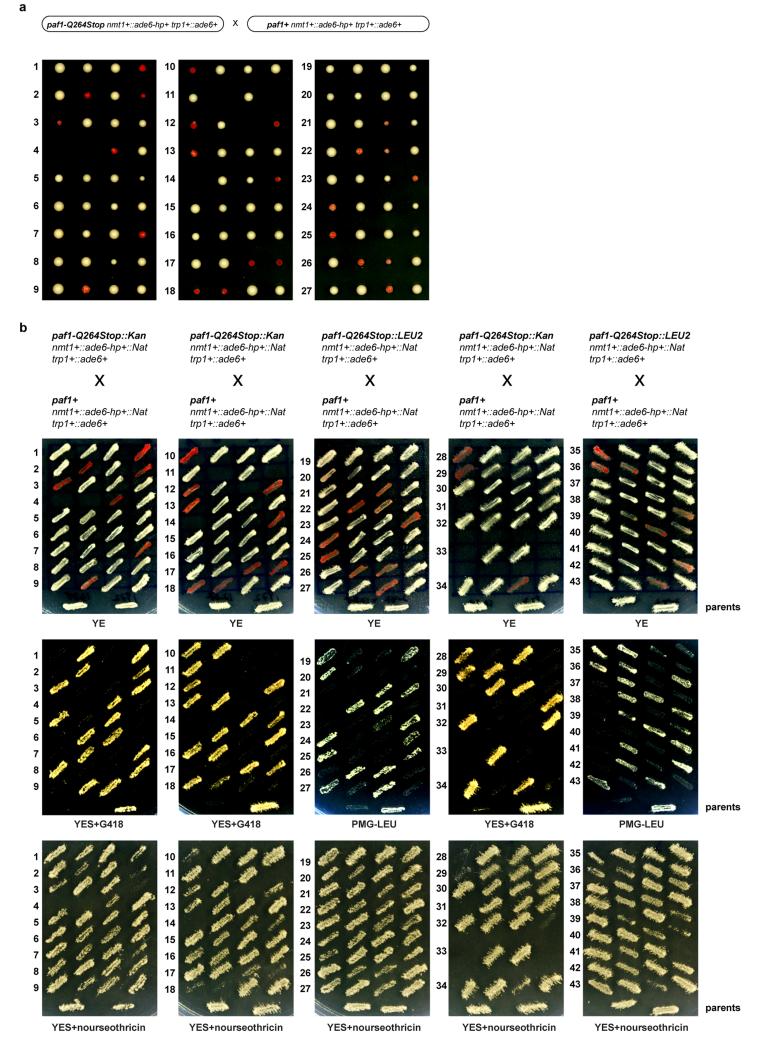

Consistent with the formation of an epigenetically distinct chromatin domain at the siRNA target loci, cells in a population of freshly generated Paf1C mutants were either fully red or white. The latter gradually became red with increasing numbers of mitotic divisions and once established, the silent state was remarkably stable (Fig. 1b, c). The fact that not all cells in a population of naïve Paf1C mutant cells turned red immediately allowed us to determine the frequency of initiation of heterochromatin formation quantitatively. This analysis revealed that silencing in mitotic cells was efficiently established in leo1-W157Stop mutant cells, whereas cdc73-G313R cells were the least efficient (Fig. 2a). Descendants of a red colony switched to the white phenotype only sporadically in all Paf1C mutants, demonstrating that maintenance of heterochromatin is very robust in these cells (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, siRNA-directed de novo formation of heterochromatin was most efficient in meiosis. In 70% of all crosses between a naïve paf1-Q264Stop mutant (white) and a paf1+ cell, at least one of two paf1-Q264Stop spores had initiated ade6+ repression (red) (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 7). We also observed highly efficient propagation of the silent state through meiosis, but only in descendants of spores that inherited the Paf1C mutation (Fig. 2d). Thus, siRNAs are sufficient to initiate the formation of very stable heterochromatin when Paf1C function is impaired.

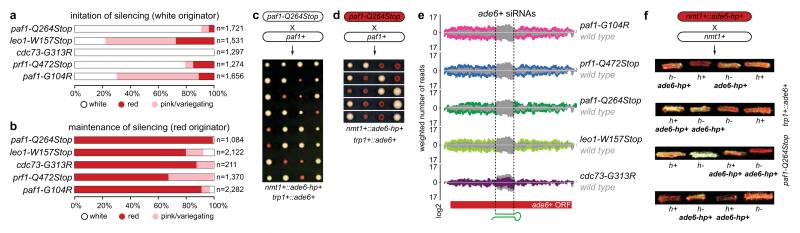

Figure 2. siRNA-mediated epigenetic gene silencing.

a, Percentage of naïve Paf1C mutant cells that establish heterochromatin within 20-30 mitotic divisions. n, number of scored colonies. b, Stability of ectopic heterochromatin in mitotic cells. n, number of scored colonies. c, Initiation of heterochromatin formation during meiosis. Naïve paf1-Q264Stop cells (white) were crossed with paf1+ cells. Spore dissection of 8 crosses is shown. d, Red paf1-Q264Stop cells (heterochromatic ade6+) were crossed with paf1+ cells to assess stability of ectopic heterochromatin through meiosis. White descendants are paf1+. e, siRNA reads mapping to the ade6+ locus in wild type (grey) and Paf1C mutant strains (colored). Read counts were normalized to library size and are shown in log2 scale. Dashed lines mark the ade6+ fragment targeted by the hairpin. f, Red paf1-Q264Stop cells (heterochromatic ade6+) carrying the ade6+-targeting hairpin (ade6-hp+) were crossed with paf1-Q264Stop cells without the hairpin to test hairpin requirement after initiation of silencing. Four spores derived from the cross were struck on YE plate to assess the silencing phenotype. h+ and h- denote mating types and ade6-hp+ marks cells carrying the hairpin.

Intriguingly, assembly of heterochromatin at the ade6+ target gene was accompanied by the production of novel ade6+ siRNAs that are not encoded in the ade6-hp and that accumulated to high levels (Fig. 2e). Thus, primary ade6-hp siRNAs trigger the production of highly abundant secondary ade6+ siRNAs in Paf1C mutants. To test whether continuous production of siRNAs is necessary for sustaining the repressed state, we deleted genes encoding for RNAi factors and found that ade6+ silencing was completely abolished in all canonical RNAi mutants. Deletion of tri1+ resulted in moderate derepression of ade6+ silencing, suggesting a minor contribution of this exonuclease to siRNA-mediated heterochromatin silencing (Fig. 1e). To test whether secondary siRNAs produced at the ade6+ target locus are sufficient to maintain heterochromatin, we crossed a trp1+::ade6+ paf1-Q264Stop ade6-hp+ strain (red) with a trp1+::ade6+ paf1-Q264Stop (white) strain. These crosses regularly produced spores that gave rise to red cells even in the absence of the nmt1+::ade6-hp+ allele. The red phenotype was still visible after replica plating, demonstrating that heterochromatin can be maintained in the absence of the primary siRNAs for hundreds of mitotic cell divisions (Fig. 2f). These results demonstrate that siRNAs can induce an epigenetic change in gene expression in meiotic and mitotic cells, and that secondary siRNA production is sufficient to propagate the repressed state for many mitotic cell divisions independently of the primary siRNAs that triggered the epigenetic switch.

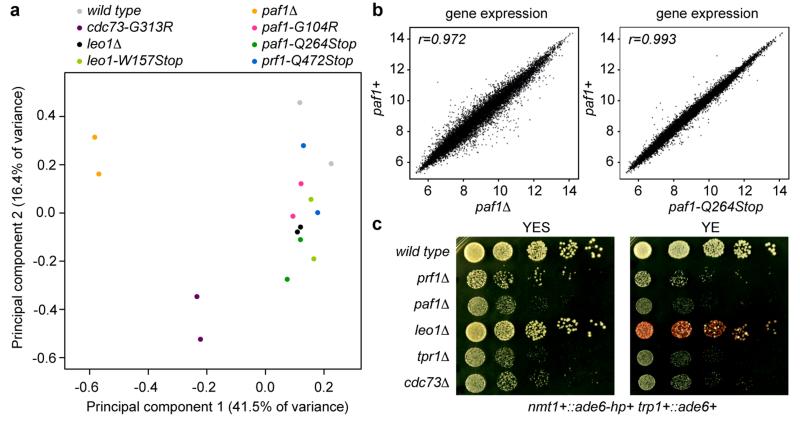

The highly conserved Paf1C is well known for promoting RNA Pol II transcription elongation and RNA 3′-end processing (Fig. 3a). Paf1C also governs transcription-coupled histone modifications and has connections to DNA damage repair, cell cycle progression, and other processes19. Given this broad function, we assessed the impact of our Paf1C mutations on genome expression. This analysis revealed that paf1-G104R, paf1-Q264Stop, prf1-Q472Stop, and leo1-W157Stop impair repression of heterochromatin formation, without affecting RNA expression globally (Supplementary Information and Extended Data Fig. 8). This is consistent with our observation that ade6+ expression is unaffected in Paf1C mutants in the absence of siRNAs (Fig. 1b). We did, however, detect a reduction in H3K36 tri-methylation and an increase in RNA Pol II occupancy on the ade6+ gene in paf1-Q264Stop cells (Fig. 3b, c). This is consistent with Paf1C’s role in promoting transcription and suggests that decelerated transcription kinetics in Paf1C mutants enables siRNA-directed epigenetic gene silencing. To dissect which of Paf1C’s activities are most critical to prevent RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly, we interfered with transcription elongation, termination, or co-transcriptional histone modification directly by mutating genes encoding elongation factors (Tfs1 and Spt4), termination factors (Ctf1 and Res2), or histone methyltransferases (Set1 and Set2) (Fig. 3a)20,21. We observed siRNA-mediated initiation of ade6+ silencing in ctf1-70 and res2Δ cells, but not in tfs1Δ, spt4Δ, set1Δ, and set2Δ cells (Fig. 3d-f), demonstrating that impaired transcription termination but not elongation is sufficient to allow siRNA-directed repression. Notably, although impaired transcription termination in ctf1-70 and res2Δ cells was sufficient to initiate silencing, the silent state was less stable than in paf1-Q264Stop mutant cells (Fig. 3e, f). This explains why our screen did not reveal mutations in transcription termination factors.

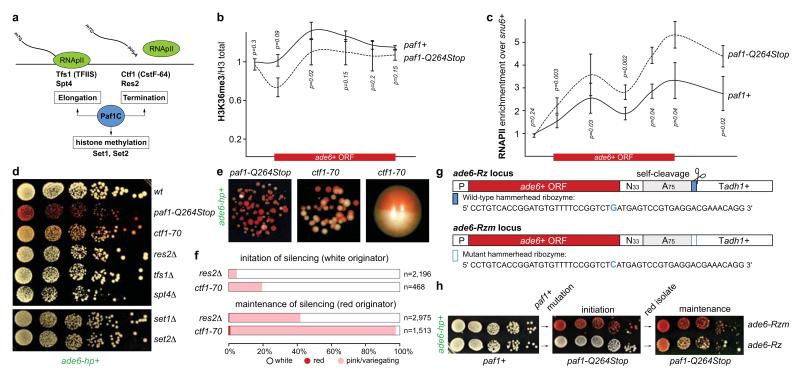

Figure 3. Mechanism of repression.

a, Paf1C governs RNA Pol II transcription elongation, RNA 3’-end processing, and transcription-coupled histone modifications. b and c, ChIP experiments to assess ade6+ transcriptional activity in Paf1C mutant cells. H3K36me3 levels were normalized to total H3 levels. snu6+ is transcribed by RNAPIII and serves as background control. Error bars, SEM; n=3 independent biological replicates; p values were calculated using one-tailed Student’s t test. d and e, Silencing assays showing that ade6+ siRNAs can initiate repression of ade6+ in transcription termination mutants. Note the bi-stable state of repression in ctf1-70 cells. Cells were grown on yeast extract (YE) plates. f, Percentage of naïve transcription termination defective cells (white originator) that establish heterochromatin within 20-30 mitotic divisions (initiation) and stability of ectopic heterochromatin in descendants thereof (maintenance). n, number of scored colonies. g, A 52-mer wild-type or mutant hammerhead ribozyme sequence preceded by a templated polyA(75)-tail was integrated 33nt downstream of the ade6+ stop codon (ade6-Rz or ade6-Rzm, respectively). h, Silencing assay showing that ade6+ siRNAs stably repress ade6-Rzm but not ade6-Rz in paf1 mutant cells. Note that ade6-Rz produces fully functional mRNA in paf1+ cells.

In ctf1-70 cells, although RNA Pol II fails to terminate, the nascent RNA is still properly processed and released from the site of transcription21. This likely accounts for the less stable silencing in ctf1-70 cells and suggests that the more severe phenotype of Paf1C mutants is due to the combined effects of impaired termination and nascent transcript release. Therefore, we tested whether artificially releasing the nascent transcript from the site of transcription partially alleviates siRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation in Paf1C mutant cells. To this end, we inserted a 52-nucleotide hammerhead ribozyme (Rz), preceded by a templated polyA (A75) tail, downstream of the ade6+ open reading frame (ade6-Rz) to induce self-cleavage of nascent ade6+ transcripts (Fig. 3g). Indeed, initiation of silencing at the ade6-Rz locus was inefficient and the repressed state was poorly propagated in paf1-Q264Stop mutant cells. In contrast, silencing was very effective in cells that harbor a single base change in the catalytic site of the Rz (ade6-Rzm) that abolishes self-cleavage (Fig. 3h). Thus, retaining the nascent transcript on chromatin is critical to stabilize the repressed state.

These results are consistent with a kinetic model for Paf1C function and demonstrate that proper transcription termination is critical to prevent de novo formation of heterochromatin by siRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 9). This is further supported by the recent observation that termination sequences in the 3’UTR of the ura4+ gene inhibit the ability of siRNAs to promote heterochromatin formation17 and is reminiscent of enhanced silencing phenotype (esp) mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana, which are in genes that encode for members of the cleavage polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) and cleavage stimulation factor (CstF) complexes22. Importantly, our results show that impairment of both transcription termination and nascent transcript release is imperative to confer stability to the repressed state, although compromised transcription termination is sufficient to initiate the formation of bi-stable heterochromatin by trans-acting siRNAs.

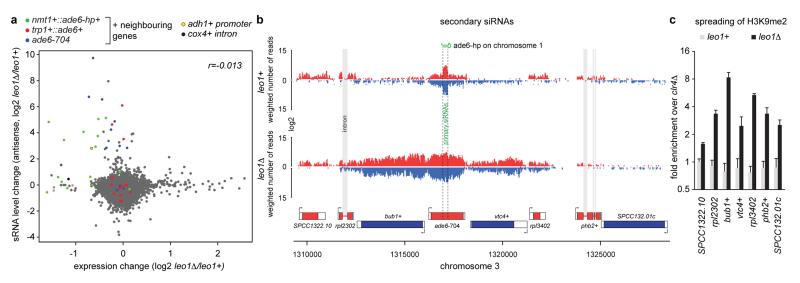

Besides Dcr1-dependent siRNAs, Ago1 associates with Dcr1-independent small RNAs referred to as primal RNAs (priRNAs). priRNAs appear to be degradation products of abundant transcripts and could potentially trigger siRNA amplification and uncontrolled heterochromatic gene silencing23. Therefore, we speculated that the physiological function of Paf1C is to protect the genome from spurious priRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation. To investigate this we analyzed whether Paf1C mutants would disclose genomic regions that could be potentially assembled into facultative heterochromatin by endogenous small RNAs. Based on our results, loci at which facultative heterochromatin forms in an RNAi-dependent manner are expected to display reduced RNA expression with a concomitant increase in siRNA production. As expected, the nmt1+::ade6-hp+, trp1+::ade6+, and ade6-704 loci fulfilled this criteria (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Moreover, we observed repression and siRNA production for genes flanking these loci, indicating spreading of heterochromatin into neighboring genes, which occurred up to 6 kb up or downstream of the ade6-hp siRNA target sites. Indeed, we observed H3K9 methylation in this region in leo1Δ cells specifically (Extended Data Fig. 10b, c). In addition to these regions, we observed siRNA-directed silencing signatures at different, non ade6+-linked genomic loci, indicating that Paf1C may indeed function to protect the genome from illegitimate repression of protein coding genes by endogenous priRNAs. However, we did not recover the same sites repeatedly in the different Paf1C mutants (Supplementary Table 1). This implies that initiation of silencing at these sites occurred stochastically and that there are no specific sites primed for the formation of facultative heterochromatin in mitotic cells that are grown under standard laboratory conditions. Therefore, we conclude that Paf1C protects protein-coding genes from unwanted long-term silencing that might occur by chance, thereby restraining phenotypic variation and conferring epigenetic robustness to the organism.

In summary, we discovered that synthetic siRNAs are highly effective in directing locus-independent assembly of heterochromatin that can be stably maintained through mitosis and meiosis only when Paf1C activity is impaired. A remarkable observation of our study is that the newly established heterochromatin was inherited for hundreds of cell divisions across generations in Paf1C mutant cells, even in the absence of the primary siRNAs that triggered the assembly of heterochromatin. This phenomenon complies with the classical definition of epigenetics24 (i.e. that it is heritable even in the absence of the initiating signal) and highlights fundamental roles of Paf1C and the RNAi machinery in building up epigenetic memory. This mechanism is also reminiscent of RNA-mediated epigenetic phenomena in higher eukaryotes such as paramutation25 and RNA-induced epigenetic silencing (RNAe)26. RNAe is a phenomenon in which small RNAs of the C. elegans Piwi pathway can initiate transgene silencing that is extremely stable across generations even in the absence of the initiating Piwi protein. Yet, not all Piwi pathway RNAs trigger RNAe27. Similarly, generation of siRNAs is necessary but not sufficient for paramutation in maize28. Thus, Paf1C may also play a regulatory role in paramutation and/or RNAe. Interestingly, Paf1C is known to help maintain expression of transcription factors required for pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells and prevent expression of genes involved in lineage specification29,30, which may also involve small RNAs and chromatin regulation.

The ability to induce long-lasting and sequence specific gene silencing by transient delivery of synthetic siRNAs without changing the underlying DNA sequence will not only enable fundamental research on mechanisms that confer epigenetic memory, but may also open up new avenues in biotechnology and broaden the spectrum of the potential applications of RNAi-based therapeutics. Epigenetic control over gene expression is of particular interest in plant biotechnology, as this would circumvent the generation of genetically modified organisms.

METHODS

Strains, Plasmids

Fission yeast strains were grown at 30°C in YES medium. All strains were constructed following a PCR-based protocol31 or by standard mating and sporulation. Plasmids and Strains generated in this study are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

EMS mutagenesis, hit selection, and Backcrossing

Exponentially growing sms0 (SPB464) cells were washed and resuspended in 50mM K-phosphate buffer (pH7.0) and treated with EMS (final concentration 2.5%) for 150 min. An equal volume of freshly prepared 10% Na-thiosulfate was then added. Cells were washed with water and subsequently resuspended in YES. EMS treatment resulted in ~50% cell viability. To screen for mutants in which ade6+ expression was silenced, cells were spread on YE plates. About 350000 colonies were examined and pink colonies were selected for further evaluation. Positive hits were backcrossed 4 times with the parental strains SPB464 or SPB1788, depending on mating type.

Silencing assays

To assess ura4+ expression, serial 10-fold dilutions of the respective strains were plated on PMGc (nonselective, NS) or on PMGc plates containing 2 mg/ml 5-FOA. To assess ade6+ expression, serial 10-fold dilutions of the respective strains were plated on YES and YE plates.

Assessment of initiation versus maintenance of ectopic heterochromatin formation

Mutant strains were seeded on YE plates and single cell-derived red or white colonies were selected. Colonies were resuspended in water and 100-500 cells were seeded on YE plates, which were then incubated at 30°C for 3 days. Images of the plates were acquired after one night at 4°C and colonies were counted automatically using Matlab (The MathWorks) and ImageJ Software (National Institutes of Health).

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis was performed as described in32.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR on cDNA samples and ChIP DNA was performed as described in33 using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table 4.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP experiments were performed as previously described in33 with minor modifications. Briefly, S. pombe cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min and then lysed in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF and protease-inhibitor cocktail. Chromatin was sheared with a Bioruptor (Diagenode). The following antibodies were used in this study: histone H3K9me2-specific mouse monoclonal antibody from Wako (clone no. MABI0307), histone H3-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody from Abcam (clone no. ab1791), histone H3K36me3-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody from Abcam (clone no. ab9050), and RNA Polymerase II mouse monoclonal antibody from Covance (clone no. 8WG16).

Small RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing cells using the hot phenol method34. The RNA was fractionated using RNeasy Midi columns (Qiagen) following the ’RNA cleanup protocol’ provided by the manufacturer. The flow-through fraction was precipitated (’small RNA’ fraction). Aliquots (25 μg) of the small RNA fraction were separated by 17.5% PAGE and the 18- to 28-nt population purified. Libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeqTM small RNA preparation protocol (Cat.# RS-930-1012). The 145- to 160-nt population was isolated and the library sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000. Small RNA reads were aligned as described previously32 with two mismatches allowed.

Whole genome sequencing

Cells from overnight culture were harvested, washed once with water and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cells were spheroplasted in spheroplast buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 100 mM KHPO4, pH 7.5, 0.5 mg ml−1 Zymolyase (Zymo Research), 1 mg ml−1 lysing enzyme from Trichoderma harzianum (Sigma)). Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Barcoded genomic DNA libraries for Illumina next-generation sequencing were prepared from 50ng genomic DNA using the Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Libraries were pooled equimolarly and sequenced on one lane of a HiSeq2000 machine (Illumina). Basecalling was done with RTA 1.13.48 (Illumina) software and for the demultiplexing CASAVA_v1.8.0 (Illumina) was used. For each strain, between 8.7 and 25.5 Mio. (mean of 14.2 Mio) 50-mer reads were generated and aligned to the Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h- genome assembly (obtained on September 17, 2008 from http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/schizosaccharomyces_group/MultiDownloads.html) using “bwa” (35, version 0.7.4) with default parameters, but only retaining single-hit alignments (“bwa samse -n 1” and selecting alignments with “X0:i:1”), resulting in a genome coverage between 26 and 85-fold (mean of 44-fold). The alignments were converted to BAM format, sorted and indexed using “samtools” (36, version 0.1.19). Potential PCR duplicates were removed using “MarkDuplicates” from “Picards” (http://picard.sourceforge.net/, version 1.92). Sequence variants were identified using GATK (37, version 2.5.2) indel realignment and base quality score recalibration using a set of high confidence variants identified in an initial step as known variants, followed by SNP and INDEL discovery and genotyping for each indivial strain using standard hard filtering parameters, resulting in a total of 270 to 274 sequence variations (mean of 280) in each strain compared to the reference genome (406 unique variations in total over all strains). Finally, variations were filtered to retain only high quality single nucleotide variations (QUAL >= 50) of EMS-type (G|C to A|T) with an alellic balance >= 0.9 (homozygous) that were not also identified in the parental strain (sms0), reducing the number of variations per strain to a number between 2 and 8 (mean of 4.6).

Expression profiling

RNA was isolated from cells collected at OD600 = 0.5 using the hot phenol method34. The isolated RNA was processed according to the GeneChip Whole Transcript (WT) Double-Stranded Target Assay Manual from Affymetrix using the GeneChip S. pombe Tiling 1.0FR. All tiling arrays were processed in R38 using bioconductor39 and the packages tilingArray40 and preprocessCore. The arrays were RMA background-corrected, quantile-normalized, and log2-transformed on the oligo level using the following command: expr <-log2(normalize.quantiles(rma.background.correct(exprs(readCel2eSet (filenames,rotated=TRUE))))). Oligo coordinates were intersected with the genome annotation and used to calculate average expression levels for individual genomic features (excluding those with <10 oligos) as well as broader annotation categories. In the latter case, multimapping oligos were counted only once per category (avoiding multiple counts from the same oligo).

Gene nomenclature

The proteins PAF1p, CDC73p, RTF1p, LEO1p, and CTR9p form a stable complex in S. cerevisiae (Paf1C). The systematic IDs of the genes encoding the S. pombe homologs of these proteins are SPAC664.03, SPBC17G9.02c, SPBC651.09c, SPBC13E7.08c, and SPAC27D7.14c, respectively. The CTR9 homolog SPAC27D7.14c is currently annotated as Tpr1. The RTF1 homolog SPBC651.09c is currently annotated as PAF-Related Factor 1 (prf1+), because rtf1+ is already used for an unrelated gene (SPAC22F8.07c). Therefore, we refer SPAC664.03, SPBC17G9.02c, SPBC651.09c, SPBC13E7.08c, and SPAC27D7.14c to as paf1+, cdc73+, prf1+, leo1+, and tpr1+, respectively, in this paper.

Extended Data

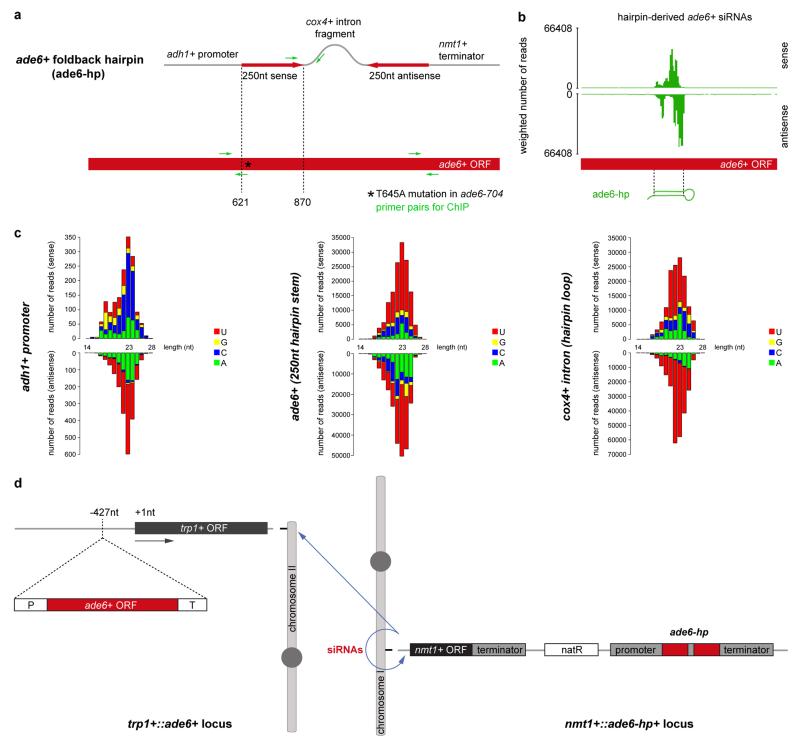

Extended Data Figure 1. Design of the ade6+ RNA hairpin (ade6-hp) construct that expresses abundant sense and antisense (primary) siRNAs.

a, The RNA stem-loop construct consists of a 250nt long ade6+ fragment, followed by a cox4+ intronic sequence and the reverse complement of the ade6+ fragment. The promoter sequence of the adh1+ gene drives expression of the RNA hairpin. Transcription of the construct is terminated by the termination signals of the nmt1+ gene. The construct was kindly provided by Dr. Tessi Iida. b and c, Small RNA sequencing revealed that the RNA stem is converted into sense and antisense siRNAs covering the 250nt stretch from the ade6+ open reading frame (nucleotides 621-870). Furthermore, sense and antisense siRNAs mapping to the cox4+ intronic and adh1+ promoter sequences are also generated when this construct is expressed in wild type cells. ORF, open reading frame; Asterisk denotes the point mutation (T645A) in the ade6-704 loss of function allele; Green arrows indicate forward and reverse primers that were used for PCR in ChIP experiments. d, schematic diagram depicting origin and target(s) of synthetic ade6-hp siRNAs. The ade6-hp expression cassette (a) was inserted into the nmt1+ locus on chromosome I by homologous recombination. The ade6-hp-containing plasmid was linearized with PmlI, which cuts in the middle of the nmt1+ terminator sequence, and transformed into ade6-704 cells. Thereby, the ade6-hp construct was inserted downstream of the nmt1+ gene. The Nat resistance cassette linked to the ade6-hp construct allowed selection of positive transformants. It also allows assessment of spreading of repressive heterochromatin that is nucleated by the ade6-hp siRNAs in cis (see Extended Data Fig. 7b). A wild type copy of the ade6+ gene was inserted upstream of the trp1+ gene on chromosome II by homologous recombination. Because the endogenous ade6-704 allele is nonfunctional, positive transformants could be selected by growth in the absence of adenine. In Paf1C mutant cells, ade6-hp derived siRNAs either act in cis to assemble heterochromatin at the nmt1+ locus (chromosome I), or in trans to direct the formation of heterochromatin at the trp1+::ade6+ (chromosome II) and ade6-704 (chromosome III) loci.

Extended Data Figure 2. Silencing assays demonstrating the inability of synthetic siRNAs to act in trans in Paf1C wild type cells.

a, ade6+ silencing assays were performed with cells expressing synthetic ade6-hp siRNAs, ura4-hp siRNAs, or no siRNAs. The ability of ade6-hp siRNAs to silence either the endogenous ade6+ gene or the trp1+::ade6+ reporter gene was assessed at different adenine concentrations. ade6-704 cells were used as positive control. b and c, ade6+ mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to act1+ mRNA. One representative biological replicate is shown. Error bars, SD. d, ade6+silencing assays demonstrating that neither the endogenous ade6+ gene nor the trp1+::ade6+ reporter gene becomes repressed by trans-acting ade6-hp siRNAs, even upon overexpression of the heterochromatin protein Swi6.

Extended Data Figure 3. Small RNA-mediated silencing (sms) forward genetic screen identifies five true positive hits that enable siRNAs to methylate H3K9 at the ade6+ gene in trans.

a, Workflow of the EMS mutagenesis screen. We mutagenized sms0 cells, which express abundant siRNAs complementary to the ade6+ gene (indicated by green hairpin), with ethylmethansulfonate (EMS) (primary screen). Subsequently, we tested the positive red colonies for growth in the absence of adenine to select against loss-of-function mutations in the adenine biosynthesis pathway (secondary screen). In hits that remained positive after the secondary screen, dcr1+ was deleted to identify truly siRNA-dependent hits (tertiary screen). For mapping of causative mutations by whole-genome next-generation sequencing, positive hits were backcrossed four times. b, sms1-10 mutants show the red ade6+ silencing phenotype on YE plates, which segregated through four successive backcrosses for all 10 mutants. The ade6-M210 loss-of-function allele and ade6+ inserted within centromeric heterochromatin (otr1R::ade6+) serve as positive controls. c, ChIP experiment demonstrating methylation of H3K9 at the ade6+ target loci in sms1, 3, 4, 6, and 8. One representative biological replicate is shown. d, ade6+ silencing in sms1, 3, 4, 6, and 8 is Dcr1-dependent. e, Resequencing of EMS-mutagenized S. pombe strains. From outside to inside, the tracks show the genomic location, the average coverage per window of 10kb (black line, scale from zero to 30), the number of sequence variations identified prior to filtering in all strains per window of 10kb (blue bars, scale from zero to 90) and the five mutations that passed the filtering and overlapped with Paf1C genes (red lines, the two mutations in Paf1 are too close to be resolved individually). f, Table lists mutations mapped by whole genome sequencing. In Dcr1-dependent mutants, we mapped mutations in the genes SPBC651.09c, SPAC664.03, SPBC13E7.08c, and SPBC17G9.02c whose homologues in budding yeast encode for protein subunits of the Paf1 complex.

Extended Data Figure 4. Mutant alleles for the homologs of all five subunits of Paf1C enable siRNAs to induce gene silencing in trans.

a, ade6+ siRNAs reduce ade6+ mRNA levels in all Paf1C mutant strains identified in this study. Whole-genome tiling arrays were used to assess gene expression in the mutant cells indicated. y-axes is in linear scale. b, C-terminally tagged Tpr1 and Cdc73 are hypomorphic. Full deletions of the tpr1+ and cdc73+ genes cause retarded growth phenotypes (Extended Data Fig. 8c). In contrast, tpr1-3xFLAG and cdc73-3xFLAG grow normally, and display ade6-hp siRNA-mediated repression of the ade6+ gene.

Extended Data Figure 5. Expression of synthetic siRNAs in paf1-Q264Stop cells is sufficient to trigger stable repression of protein coding genes in trans.

a, Left: The paf1-Q264Stop mutation was introduced into cells that express synthetic ura4-hp siRNAs15. Right: Wild type (paf1+) and paf1-Q264Stop were grown in the presence or absence of 5-FOA. Red arrow indicates paf1-Q264Stop colonies growing on FOA-containing medium. Note that these colonies could be propagated in non-selective medium without losing the repressed state. b, In S. pombe, artificial tethering of the RITS complex to mRNA expressed from the endogenous ura4+ locus using the phage λN protein results in de novo generation of ura4+ siRNAs. These siRNAs load onto RITS and are necessary to establish heterochromatin at the ura4+ locus in cis. However, like ura4-hp siRNAs, they are incapable of triggering the repression of a second ura4+ locus in trans18. To test whether ura4+ siRNAs produced as a result of Tas3λN tethering to ura4+::5BoxB mRNA (chromosome III) can act in trans to silence a second ura4+ allele (leu1Δ::ura4+, chromosome II), paf1+ was mutated and ura4+ repression was assessed by FOA silencing assays. Whereas 5-FOA was toxic to both paf1+ and paf1-Q264Stop cells in the absence of ura4+ siRNAs (Tas3 not fused to λN), FOA resistant colonies appeared upon Tas3-λN tethering, demonstrating that siRNAs generated from the ura4+::5BoxB locus can initiate repression of the second ura4+ copy expressed from the leu1+ locus. Notably, siRNA-mediated ura4+ repression in trans was more pronounced in the absence of the RNAse Eri1. We have previously shown that the levels of ura4+::5BoxB-derived siRNA are higher in eri1Δ cells41. We note that trans-silencing of the second ura4+ allele occasionally occurs in paf1+ cells in the absence of Eri118. However, in contrast to paf1-Q264Stop cells, the repressed state of ura4+ is not stably propagated. Hairpin symbols downstream of the ura4+ ORF denote BoxB sequences. They form stem loop structures when transcribed and are bound by the λN protein. c, ade6+ silencing assay demonstrating that also the endogenous ade6+ gene is repressed if ade6-hp siRNAs are expressed from the nmt1+ locus in paf1-Q264Stop cells. Silencing assay was performed with two freshly generated (naïve) paf1-Q264Stop mutant strains. A few white colonies in which heterochromatin has not yet formed are discernable. Such white colonies were picked to determine heterochromatin initiation frequencies shown in figure 2.

Extended Data Figure 6. ade6+ siRNAs trigger de novo methylation of H3K9 at homologous ade6+ sequences in cis and in trans.

a, ade6-hp RNA producing locus and siRNA targe loci in trans in the sms0 strain. ade6-704 is a loss-function allele of the endogenous ade6+ gene and serves as a positive control in the silencing assays. b and c, ade6+ siRNAs direct the methylation of H3K9 at ade6 targets in cis (green) and in trans (red) in Paf1C mutant cells. H3K9me2 for tpr1+::ade6+ is shown in figure 1d. Quantitative PCR was performed with locus-specific primers. Error bars, SEM; n=3 technical replicates. d and e, ChIP experiments to assess ade6+ transcriptional activity. H3K36me3 levels were normalized to total H3 levels. snu6+ is transcribed by RNAPIII and serves as background control. Error bars, SEM; n=3 independent biological replicates; p values were calculated using the one-tailed Student’s t test.

Extended Data Figure 7. Pronounced siRNA-directed heterochromatin formation in trans during meiosis.

a, White (naïve) cells that had not yet established heterochromatin at the trp1+::ade6+ locus were isolated from populations of freshly generated paf1-Q264Stop strains and crossed with paf1+ cells. Both mating partners expressed ade6-hp siRNAs and contained the same trp1+::ade6+ reporter. Spores were dissected on YE plates and incubated for 3-4 days at 30°C. Note the non-Mendelian inheritance pattern of the parental white phenotype and the high incidence of heterochromatin formation (red phenotype) in paf1-Q264Stop cells after meiosis. b, Spores from 43 tetrads were dissected in total. Colonies formed by the individual spores (a) were then struck on YE plates and incubated for 3-4 days at 30°C, followed by replica-plating onto YES-G418 and YES+nourseothricin (Nat) plates for genotyping. Thus, the cells visible on the YE plates have gone through roughly 50-80 mitotic divisions after mating and sporulation. This analysis shows that de novo formation of heterochromatin by trans-acting siRNAs during meiosis occurs more frequently than in mitosis. However, once established, heterochromatin is remarkably stable in mitotic cells (see also figure 2). Intriguingly, growth of some paf1-Q264Stop descendants was reduced on YES+nourseothricin plates, demonstrating spreading of heterochromatin into the neighboring Nat-resistance cassette that marks the nmt1+::ade6-hp+ locus (see Extended Data Fig. 1). Note that genes repressed by heterochromatin can be derepressed under strong negative selection. Thus, this observation indicates extraordinary repressive activity of the heterochromatin that forms in cis at the ade6-hp siRNA-producing locus. Finally, note that paf1+ cells (no growth on YES-G418 or PMG-LEU) never turned red, demonstrating the high repressive activity of Paf1. This explains unsatisfactory results of previous attempts to induce the formation of stable heterochromatin in trans by expressing synthetic siRNAs.

Extended Data Figure 8. Effect of Paf1C mutations on global gene expression and silencing.

a, The impact of the Paf1C mutations on genome expression was assessed by hybridizing total RNA to whole-genome tiling arrays. The parental wild type strain, all Paf1C point mutations discovered in the screen, and full deletions of the paf1+ and leo1+ genes were included in the analysis. In order to compare the genome-wide expression profiles of the mutants with the wild type strain, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the data obtained for two biological replicates of each strain. Principal Component (PC) 1 and 2 explained 41.5% and 16.4% of the variance between samples and were selected for visualization, revealing that cdc73-G313R and paf1Δ cells are most different from wild type cells. All the other mutants clustered together in a group of samples that also includes wild type, demonstrating that RNA steady-state levels are only minimally affected in these mutants. Note that leo1Δ is more similar to wild type than paf1Δ, as well as that paf1Δ clusters separately from the Paf1C point mutants. b, Pairwise comparisons of gene expression between wild type and paf1 mutant strains. c, leo1Δ cells have no growth defect but are susceptible for de novo formation of heterochromatin by siRNAs acting in trans. These results suggest that Leo1 might be a bona fide repressor of small RNA-mediated heterochromatin formation.

Extended Data Figure 9. Kinetic model for Paf1C-mediated repression of siRNA-directed heterochromatin formation.

a, Paf1C facilitates rapid transcription and release of the nascent transcript from the DNA template. Because the kinetics of transcription termination and RNA 3’ end processing is faster than RITS binding and CLRC recruitment, stable heterochromatin and long lasting gene silencing cannot be established. b, In Paf1C mutant cells identified in this study, elongation of RNA polymerase II, termination of transcription, and the release of the nascent transcript from the site of transcription is decelerated. This results in an accumulation of RNA polymerases that are associated with nascent transcripts, opening up a window of opportunity for the siRNA-guided RITS complex to base-pair with nascent transcripts and recruit CLRC. Consequently, highly stable and repressive heterochromatin is assembled, which is accompanied by the generation of secondary siRNAs covering the entire locus (not depicted in this scheme). Notably, our results demonstrate that impaired transcription termination but not elongation is sufficient to allow silencing. However, to confer robustness to the repressed state, both transcription termination and release of the RNA transcript from site of transcription must be impaired concomitantly.

Extended Data Figure 10. Formation of ectopic heterochromatin.

a, Differential gene expression compared to differential antisense siRNA expression in leo1Δ. Gene expression profiles were obtained with whole-genome tiling arrays and small RNA profiles by deep sequencing. Genes neighboring the nmt1+::ade6-hp+, trp1+::ade6+, and ade6-704 loci are marked in color (see also Supplementary Table 1). b, siRNA reads mapping to the ade6-704 locus in leo1+ and leo1Δ strains. Red, plus strand; blue, minus strand. Intronic rpl2302 siRNAs in leo1Δ cells indicate co-transcriptional dsRNA synthesis by RDRC prior to splicing. c, ChIP experiment showing H3K9me2 enrichments on genes surrounding the ade6-704 locus in leo1+ and leo1Δ cells. Enrichments were calculated relative to background levels obtained in clr4Δ cells and normalized to adh1+. Error bars, SD; mean of n=2 independent biological replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Tetsushi Iida for providing the plasmid encoding the ade6-hp construct, Nathalie Laschet and Rikako Tsuji for technical assistance, Stéphane Thiry for hybridizing tiling arrays, Kirsten Jacobeit and Sophie Dessus-Babus for small RNA sequencing, Tim Roloff for archiving data sets, Moritz Kirschmann for developing the Matlab script for colony counting, and Alex Tuck for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funds from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council, and the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. The Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research is supported by the Novartis Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Genome-wide data sets are deposited at GEO under the accession number GSE59171.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moazed D. Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature. 2009;457:413–420. doi: 10.1038/nature07756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volpe TA, et al. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 2002;297:1833–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1074973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verdel A, et al. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science. 2004;303:672–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1093686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motamedi MR, et al. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schalch T, et al. High-affinity binding of Chp1 chromodomain to K9 methylated histone H3 is required to establish centromeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2009;34:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castel SE, Martienssen RA. RNA interference in the nucleus: roles for small RNAs in transcription, epigenetics and beyond. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2013;14:100–112. doi: 10.1038/nrg3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan SW, Zhang X, Bernatavichute YV, Jacobsen SE. Two-Step Recruitment of RNA-Directed DNA Methylation to Tandem Repeats. PLoS.Biol. 2006;4:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mette MF, Aufsatz W, van der Winden J, Matzke MA, Matzke AJ. Transcriptional silencing and promoter methylation triggered by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:5194–5201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ting AH, Schuebel KE, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Short double-stranded RNA induces transcriptional gene silencing in human cancer cells in the absence of DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2005;37:906–910. doi: 10.1038/ng1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris KV, Chan SW, Jacobsen SE, Looney DJ. Small Interfering RNA-Induced Transcriptional Gene Silencing in Human Cells. Science. 2004 doi: 10.1126/science.1101372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Villeneuve LM, Morris KV, Rossi JJ. Argonaute-1 directs siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2006;13:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janowski BA, et al. Involvement of AGO1 and AGO2 in mammalian transcriptional silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:787–792. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napoli S, Pastori C, Magistri M, Carbone GM, Catapano CV. Promoter-specific transcriptional interference and c-myc gene silencing by siRNAs in human cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1708–1719. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmer F, et al. Hairpin RNA induces secondary small interfering RNA synthesis and silencing in trans in fission yeast. EMBO reports. 2010;11:112–118. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iida T, Nakayama J, Moazed D. siRNA-mediated heterochromatin establishment requires HP1 and is associated with antisense transcription. Molecular cell. 2008;31:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbogning J, et al. The PAF complex and Prf1/Rtf1 delineate distinct Cdk9-dependent pathways regulating transcription elongation in fission yeast. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1004029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004029. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu R, Jih G, Iglesias N, Moazed D. Determinants of heterochromatic siRNA biogenesis and function. Molecular cell. 2014;53:262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buhler M, Verdel A, Moazed D. Tethering RITS to a Nascent Transcript Initiates RNAi- and Heterochromatin-Dependent Gene Silencing. Cell. 2006;125:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomson BN, Arndt KM. The many roles of the conserved eukaryotic Paf1 complex in regulating transcription, histone modifications, and disease states. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1829:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung AC, Cramer P. A movie of RNA polymerase II transcription. Cell. 2012;149:1431–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.006. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aranda A, Proudfoot N. Transcriptional termination factors for RNA polymerase II in yeast. Mol.Cell. 2001;7:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herr AJ, Molnar A, Jones A, Baulcombe DC. Defective RNA processing enhances RNA silencing and influences flowering of Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:14994–15001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606536103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606536103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halic M, Moazed D. Dicer-independent primal RNAs trigger RNAi and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2010;140:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ptashne M. On the use of the word ‘epigenetic’. Current biology : CB. 2007;17:R233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler VL. Paramutation: from maize to mice. Cell. 2007;128:641–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luteijn MJ, Ketting RF. PIWI-interacting RNAs: from generation to transgenerational epigenetics. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2013;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrg3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luteijn MJ, et al. Extremely stable Piwi-induced gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:3422–3430. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandler VL. Paramutation’s properties and puzzles. Science. 2010;330:628–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1191044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding L, et al. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ponnusamy MP, et al. RNA polymerase II associated factor 1/PD2 maintains self-renewal by its interaction with Oct3/4 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3001–3011. doi: 10.1002/stem.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahler J, et al. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emmerth S, et al. Nuclear retention of fission yeast dicer is a prerequisite for RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly. Developmental cell. 2010;18:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller C, et al. HP1(Swi6) Mediates the Recognition and Destruction of Heterochromatic RNA Transcripts. Molecular cell. 2012;47:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leeds P, Peltz SW, Jacobson A, Culbertson MR. The product of the yeast UPF1 gene is required for rapid turnover of mRNAs containing a premature translational termination codon. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2303–2314. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature genetics. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ihaka R GRR. A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huber W, Toedling J, Steinmetz LM. Transcript mapping with high-density oligonucleotide tiling arrays. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1963–1970. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buhler M, Haas W, Gygi SP, Moazed D. RNAi-Dependent and -Independent RNA Turnover Mechanisms Contribute to Heterochromatic Gene Silencing. Cell. 2007;129:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.