Abstract

Background

Alzheimer neuropathology is found in almost half of patients with nonsemantic primary progressive aphasia (PPA). This study examined hippocampal abnormalities in PPA to determine similarities to those described in amnestic Alzheimer disease.

Methods

In 37 PPA patients and 32 healthy controls, we generated hippocampal subfield surface maps from structural magnetic resonance images and administered a face memory test. We analyzed group and hemisphere differences for surface shape measures and their relationship with test scores and APOE genotype.

Results

The hippocampus in PPA showed inward deformity (CA1 and subiculum subfields) and outward deformity (CA2–4 + dentate gyrus subfield) and smaller left than right volumes. Memory performance was related to hippocampal shape abnormalities in PPA patients, but not controls, even in the absence of memory impairments.

Conclusions

Hippocampal deformity in PPA is related to memory test scores. This may reflect a combination of intrinsic degenerative phenomena with transsynaptic or Wallerian effects of neocortical neuronal loss.

Keywords: Frontotemporal dementia, Lobar degeneration, Multiatlas mapping, Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Memory, Neuroanatomy, Primary progressive aphasia (PPA), Alzheimer's disease (AD)

1. Introduction

The clinical course of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is characterized by the initial progressive loss of language abilities and relative preservation of other cognitive functions, such as episodic memory [1]. There are three subtypes of PPA, each based on the most prominent type of language deficit in the clinical profile [2], but the preservation of memory is most easily demonstrated in nonsemantic PPA subtypes, namely, the agrammatic and logopenic variants, because they have relatively preserved language comprehension. Neuropathologically, PPA is heterogeneous: although the amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease (AD) are predominant in the brains of some PPA patients, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology is predominant in others [3], [4], [5]. Post-mortem studies have revealed that the prevalence of AD pathology in nonsemantic PPA subtypes ranges from 30% to 60% [4], [5], [6], [7], and is highest in the logopenic subtype [4], [6], [8]. Although a significant accumulation of neurofibrillary AD pathology can be seen in the hippocampus/entorhinal cortex of PPA patients, its entorhinal-to-neocortical ratio is lower in PPA when compared with this ratio in post-mortem analysis of individuals with the more typical amnestic dementia of AD [3].

Medial temporal neurofibrillary pathology is the most characteristic feature of AD pathophysiology [9], [10]. In AD associated with the amnestic dementia of the AD type (DAT), the neurofibrillary tangles accumulate in the entorhino-hippocampal complex at the earliest stages of the disease, even before symptom onset [11], [12], [13], and lead to regional atrophy of hippocampal subfields [14] and entorhinal [15] cortices as the disease progresses. In DAT, deficits in visual and verbal memory are known to correlate with both post-mortem neuropathological measures [16] and in vivo atrophy of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus [11].

Although neuroimaging has revealed atrophy of the left hemisphere language network in PPA [17], less consistency is found in the hippocampus. For example, van de Pol et al. [18] found no significant hippocampal atrophy in patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia, but Gorno-Tempini et al. [19] found atrophy of the anterior left hippocampus in a nonsemantic logopenic subtype. A study of nine patients with nonsemantic progressive nonfluent aphasia and 21 controls found no overall total hippocampal volume difference between groups, although the left was smaller than the right in the patient group [20]. Using spherical harmonics, the same study found inward deformity in the patients' left hippocampus relative to the controls. These studies tended to have small sample sizes and all but one study examined only volumes but not shape, factors that may have contributed to inconsistent results.

The goal of this study was to compare the shape of the hippocampal surface, including its subfields, between PPA subjects and matched controls. We predicted a spectrum of hippocampal deformity in PPA based on the fact that some might have AD neuropathology, whereas others might not. We also predicted a greater degree of deformity in the left hippocampus, reflective of the left hemispheric focus of PPA. Study methodology involved a new multiatlas FreeSurfer-initiated Large-Deformation Diffeomorphic Metric Mapping (ma-FSLDDMM) procedure for the mapping of the hippocampal structure, and the assessment of nonverbal memory to correlate with hippocampal morphology. ma-FSLDDMM was based on our previously published single-atlas technique (sa-FSLDDMM) [21], [22], for automated brain segmentation in high-resolution structural scans which combined initial FreeSurfer segmentation of gray and white matter structures (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) with a smoothed approximation via Large-Deformation Diffeomorphic Metric Mapping (LDDMM) [23]. Compared with single-atlas methods, approaches that combine maps from multiple atlases that best match any individual subject's scan features have been shown to improve segmentation accuracy and reduce biases [24]. We chose the nonverbal Faces subtest in the Wechsler Memory Scale III (WMS-III) [25] to assess episodic memory. Although even an apparently nonverbal memory test can elicit internal verbalization [26], this choice avoided the pitfalls of using story or word-list recall to test episodic memory in patients with PPA [19], [27]. Finally, the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein ε (ApoE) gene has been revealed as a risk factor for amnestic but not aphasic dementias [28]. Because the genotype does not predict AD pathology in PPA, we hypothesized that the presence of the ApoE ε4 allele would not influence a patient's hippocampal shape or memory performance.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and assessments

The present study consisted of the analysis of data derived from a larger PPA Research Program at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and included 37 PPA and 32 control participants. The protocol for recruitment, comprehensive assessment of language and nonlanguage cognitive functions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning, and ApoE genotyping was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University; informed consent was obtained before evaluation.

All participants were right-handed. Diagnoses were established by consensus from experienced clinicians (MM, SW) according to previously published criteria [2] based on clinical interview, cognitive testing with the Uniform Data Set of the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers program [29], and review of prior diagnostic tests such as MRI and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans. ApoE genotyping was completed at Northwestern University using previously described methods [28]. PPA participants had obtained the diagnoses of PPA-G (nonfluent, agrammatic) and PPA-L (logopenic) variants, referred to in this article as nonsemantic variants. Aphasia severity was assessed using the Aphasia Quotient score from the Western Aphasia Battery [30] containing subtests of auditory comprehension, naming, repetition, and spontaneous speech.

Episodic memory was assessed using the WMS-III Faces subtest of visual-nonverbal recognition memory [25]. A similar test, the Warrington Recognition Memory Test (RMT), which assesses the immediate recognition of both words and faces, has been shown to be sensitive to hippocampal damage [31]. The WMS-III Faces test was chosen because of the addition of a delayed recognition condition, whereas the RMT tests only immediate recognition. On tests of visual memory, particularly memory for faces, participants benefit from mental verbalization of stimuli [26]. However, because WMS-III Faces is primarily visually mediated, this test may to a degree circumvent verbal deficits of PPA. Because face encoding involves primarily the right medial temporal lobe and right dorsal frontal cortex [32], PPA patients' greater left-sided cortical atrophy [33] may disrupt the face-encoding system to a lesser extent than other modalities. Participants first studied 24 faces, presented serially for 2 seconds each. Immediately afterward, these faces were presented serially among 24 novel faces, and the participant selected the previously presented faces. Then, following a 25- to 35-minute delay, participants were given a similar test of the 24 original faces, to be discriminated from yet a third set of novel faces. Accuracy scores (hits) from these immediate and delayed recognition tests were recorded.

2.2. MR scanning and ma-FSLDDMM

Magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequences (repetition time = 2.3 seconds, echo time = 2.86 milliseconds, flip angle = 9°, field of view = 256 mm, 160 slices, resolution = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) were obtained on a Siemens TIM Trio 3-Tesla system using a 12-channel head coil.

Hippocampal segmentations were generated using ma-FSLDDMM, which consisted of a 38-scan multiatlas library and their expert manual segmentations. The manual segmentations followed the delineation protocol described in Haller et al. [34] See Table 1 for descriptions of the multiatlas library and Fig. 1 for descriptions of the ma-FSLDDMM procedure.

Table 1.

Multiatlas library for ma-FSLDDMM

| Study source/reference | Brief description, scan type | N (group) | Demographics mean (SD) age, M/F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | 3T scans manually segmented by one of the authors (AC/JR) | 14 (control) | Age = 61.9 (7.2), M/F = 7/7 |

| Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative [35] | 1.5 T scans manually segmented by one of the authors (AC) | 10 (three control/three MCI/four AD) | Control: Age = 75.3 (2.1), M/F = 0/3 MCI: Age = 67.7 (10.2), M/F = 1/2 AD: Age = 76.8 (5.9), M/F = 1/3 |

| Unpublished data | 3T scans with manual segmentation (LW) | 8 (control) | Age = 75.4 (8.3), M/F = 6/2 |

| University of New South Wales Memory and Ageing Study [36] | 3T scans with manual segmentation (Sachdev et al.) | 6 (control) | Age = 77.1 (4.5), M/F = 4/2 |

Abbreviations: ma, multiatlas; FSLDDMM, FreeSurfer-initiated Large-Deformation Diffeomorphic Metric Mapping; SD, standard deviation; M/F, male/female; MCI, mild cognitive impairment patients; AD, Alzheimer's disease patients.

NOTE. This library is composed of 38 scans and their expert manual segmentations. Manual segmentations followed the delineation protocol described in Haller et al. [34].

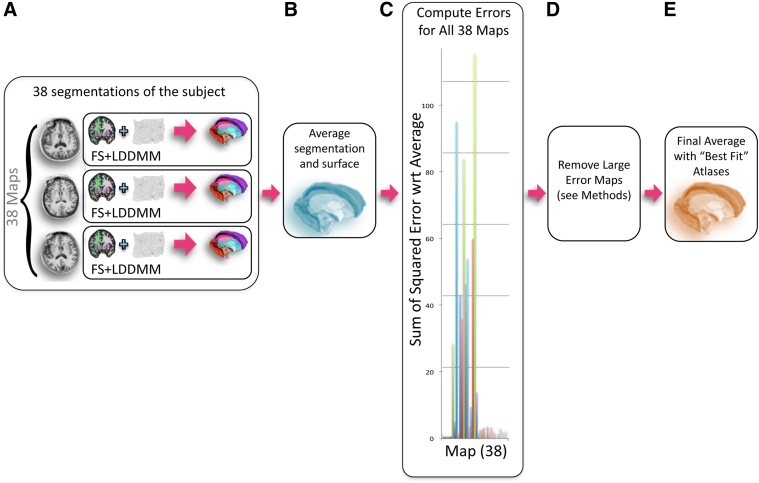

Fig. 1.

Atlas-based segmentation multiatlas FreeSurfer-initiated Large-Deformation Diffeomorphic Metric Mapping (ma-FSLDDMM) with selection, illustrated for a single subject. (A) Thirty-eight individual single-atlas FSLDDMM hippocampal segmentations and a voxel-wise average were first generated for the subject. (B) Surfaces with corresponding vertices were created for each of the 38 segmentations and the average, using a previously developed template surface injection procedure [37], [38]. (C) Sum-of-squared errors between the average surface and each sa-FSLDDMM surface were calculated. (D) Across all subjects, 14 sa-FSLDDMM maps consistently showed substantially larger error than others and were subsequently removed from further analysis. (E) New average segmentation.

In the ma-FSLDDMM procedure, 38 individual sa-FSLDDMM hippocampal segmentations and a voxel-wise average were first generated for each subject (Fig. 1A, B). Next, surfaces with corresponding vertices were created for each of the 38 segmentations and the average, using a previously developed template surface injection procedure (Fig. 1B) [37], [38]. Then, sum-of-squared errors between the average surface and each sa-FSLDDMM surface were calculated (Fig. 1C). Across all subjects, 14 sa-FSLDDMM maps consistently showed substantially larger error than others and were subsequently removed from further analysis (Fig. 1D), giving rise to a new average segmentation (Fig. 1E). Finally, an expert rater (AC) inspected the new average segmentation embedded in the MR scan, and made minor manual edits whenever necessary. We separately demonstrated high reliability for manual editing in 10 randomly selected scans (five patients and five controls)—volume intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.945 (AC/JR). A final hippocampal surface was generated by injection [37], [38].

The final surface was adjusted for individual head size by multiplying vertex coordinates by a scaling factor, defined as the cubic root of (population average intracranial volume/individual intracranial volume) [39], where intracranial volumes were provided by FreeSurfer. Adjusted hippocampal volume was calculated as volume enclosed within the hippocampal surface. Adjusted hippocampal surfaces were used in subsequent shape analysis.

2.3. Hippocampal shape and volume comparison

To visualize between-group shape differences, whole hippocampal surfaces were first rigidly aligned into a previously established template space [38], and a population average was generated. Perpendicular displacements were computed between corresponding vertices from this average to each subject. T-scores between the patient and control displacements were calculated and visualized. The CA1, subiculum, and combined CA2, 3, 4, and dentate gyrus (CA2–4 + DG) hippocampal subfields were delineated on the surface along previously defined and validated borders during the template injection procedure [40]. Previously, a team of neuroanatomy experts had manually segmented the CA1, CA2, CA3, CA4, DG, and subiculum subfields in coronal sections of the template MR scan [40] using reference sections based on the Duvernoy neuroanatomical atlas [41]. These subfield segmentations were projected onto the template surface. CA2, CA3, CA4, and DG were combined into a single CA2–4+DG as in prior studies because of their limited size and hence limited accuracy and reliability of defining each individually [12], [42]. However, this combination restricts the ability to make specific inferences for these individual subfields. Shape measures were calculated for the whole hippocampus, and individually for each of the three subfields via principal component analysis of the displacements. Ten principal components (PCs) accounting for at least 90% of the variance in whole or subfield displacements were used in statistical analyses.

The data for the present study consisted of volume, shape PC scores for the whole hippocampus, shape PC scores for each subfield, memory test scores, and demographic variables. Age and education were used as covariates, because normative scores on cognitive tests decline with age, and are frequently higher for those with advanced education [25]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS [43].

Main effects of group (between-subjects factor), hemisphere (within-subjects repeated factor), and group-by-hemisphere interactions on hippocampal volume and on whole hippocampus and subfield shape PC scores were tested using repeated-measures analysis of variance (within-subject repeated PC factor was not tested). Significance was corrected for multiple comparisons of three subfields by setting the significance level at P = .017 (i.e., 0.05/3). WMS-III Faces scores were analyzed with the analysis of covariance and independent sample t-tests (APOE ε4 present/absent).

Correlations between measures of shape and cognitive performance were explored within the PPA group. To do this, shape summary scores were generated for each subject, separately for the whole hippocampus and each subfield in each hemisphere, by applying stepwise logistic regression procedures to the respective shape PC scores. These scalar summary scores represented a continuum of overall shape variation (i.e., as opposed to individual PCs which represented dimensions of shape variation) such that a more positive shape summary score would indicate a more abnormal shape. Pearson correlation coefficients between the summary scores and WMS-III Faces Immediate and Delay scores were computed within the PPA group and within the control group separately. Significance was not corrected for the number of subfields and type of WMS-III Faces scores (immediate or delayed) because of the exploratory nature of the analysis [44].

3. Results

3.1. Participants and assessments

PPA and controls did not differ in age, gender, and education, nor in WMS-III Faces raw scores and scaled scores (the latter based on comparison with published norms) [25] (Table 2). Across groups, the raw scores on the WMS-III Faces tests were positively correlated with education as expected (immediate: Pearson's r = 0.35, P = .005; delay: r = 0.40, P = .001), and negatively correlated with age only for delayed memory (immediate: r = −0.16, P = .20; delay: r = −0.25, P = .049). Normatively, on the WMS-III Faces test, three PPA patients performed in the mildly impaired range (i.e., equivalent to the 9th percentile) for immediate recognition, and one of those three also for delayed recognition. Two control subjects also performed in the mildly impaired range for immediate recognition, and one for delayed recognition.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| PPA, n = 37 | Control, n = 32 | |

|---|---|---|

| M/F (% male) | 16/21 (43.2%) | 16/16 (50%) |

| Mean (SD) age in years | 64.9 (7.2) | 62.5 (7.0) |

| Mean (SD) education in years | 16.1 (2.1) | 15.8 (2.5) |

| Race (Caucasian/Asian/African American) | 37/0/0 | 26/1/5* |

| Mean (SD) [range] WAB Aphasia Quotient | 86.9 (7.5) [73.9-97.2] | – |

| Mean (SD) [range] | n = 34 | n = 28 |

| Immediate Raw Score | 35.9 (5.0) [26-44] | 37.4 (3.8) [27-43] |

| Delay Raw Score | 37.3 (4.3) [28-45] | 37.6 (3.5) [29-45] |

| Immediate Scaled Score | 11.1 (3.3) [6-17] | 11.7 (2.7) [6-17] |

| Delay Scaled Score | 12.5 (3.3) [6-18] | 12.3 (2.6) [6-18] |

Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; SD, standard deviation, WAB, Western Aphasia Battery.

NOTE. The demographic information of the study sample and WMS-III, Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition (WMS-III Faces) raw and scaled scores for Immediate and Delayed recognition. On the WMS-III Faces test, three PPA patients performed in the mildly impaired range for Immediate Recognition, with one of those three also for Delayed Recognition. Two control subjects also performed in the mildly impaired range for Immediate Recognition, and one for Delayed Recognition (normal: scaled score greater than 6, mild impairment: 5–6, moderate: 3–4, severe: 1–2). The WAB was administered only to PPA patients, because healthy adults are expected to obtain a perfect score of 100. Lower scores signify increasing language deficits [45].

*P < .01.

3.2. Volume and shape comparison

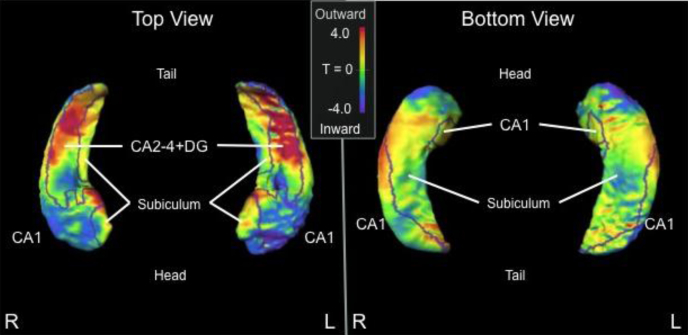

There was no group difference for whole hippocampal volume [mean (SD) = PPA: left = 1912 (240) mm3, right = 1992 (238) mm3; control: left = 1993 (204) mm3, right = 1977 (188) mm3; F(1,65) = 2.4, P = .13]. Whole hippocampal shape comparison using PC scores showed significant group difference [F(9,57) = 6.9, P < .001], with both inward (indicated by cooler shades) and outward deformities (indicated by warmer shades) observed in PPA (Fig. 2). CA1 and subiculum subfields showed mostly inward deformity [F(9,57) = 3.2, P < .01; F(9,57) = 2.8, P < .01, respectively], and CA2–4+DG showed mostly outward deformity [F(9,57) = 4.3, P < .001].

Fig. 2.

Shape comparison (T-score) between PPA vs. control subjects. Cooler shades represent a greater inward deformity of the PPA group relative to controls, whereas warmer shades represent greater outward deformity of the PPA group relative to controls. Borders on the surfaces indicate the CA1, subiculum, and CA2–4+DG subfield divisions. Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; CA2–4+DG, CA2, 3, 4 and dentate gyrus.

With regard to left-right asymmetry, a significant group-by-hemisphere interaction was found in volume [F(1,65) = 9.7, P = .003], primarily driven by a leftward asymmetry of volume loss within the PPA group. Also, significant group-by-hemisphere interactions were found in the shape of the whole hippocampus [F(9,57) = 4.5, P < .001], and in CA1 [F(9,57) = 3.0, P < .01] and CA2–4+DG [F(9,57) = 4.0, P < .001] subfields, driven by a greater effect of left hippocampal deformity (e.g., whole hippocampus mean PC effect size: left ηp2 = .06, right ηp2 = .03).

3.3. Correlation of hippocampal shape and volume with visual memory scores

Hippocampal shape summary scores were derived from discriminant function analyses (i.e., stepwise logistic regression) on the PC scores, and were positive for the PPA (i.e., diseased) and negative for the controls across all PCs (Table 3). Because these summary scores represent a continuum of overall shape variation, they were used to examine the relationship between shape and cognition.

Table 3.

Mean hippocampal shape summary scores in PPA and control subjects

| Mean (SD) | PPA | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Whole hippocampus, left | 0.97 (1.26) | −0.67 (1.24) |

| Whole hippocampus, right | 0.49 (0.76) | −0.27 (1.00) |

| CA1, left | 1.09 (1.56) | −0.68 (1.24) |

| CA1, right | 0.97 (1.25) | −0.72 (1.43) |

| Subiculum, left | 0.68 (1.18) | −0.41 (0.92) |

| Subiculum, right | 0.43 (0.75) | −0.15 (0.79) |

| CA2–4+DG, left | 1.44 (1.75) | −1.06 (1.50) |

| CA2–4+DG, right | 0.64 (0.85) | −0.47 (1.26) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; CA2–4+DG, CA2, 3, 4 and dentate gyrus.

NOTE. Note that the mean scores for the PPA subjects are positive and for controls are negative. This signifies that scores that are more positive represented hippocampal shape that deviated farther from the control group and are indicative of PPA characteristics, whereas negative scores are indicative of control characteristics.

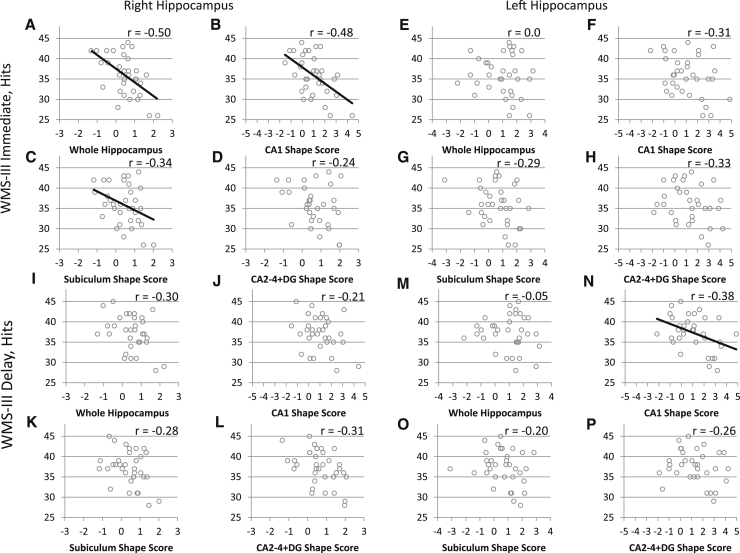

Within the PPA group, lower immediate visual memory scores were correlated with increased shape deformity in the right whole hippocampus (r = −0.50, P < .01), CA1 (r = −0.48, P = .01), and subiculum (r = −0.34, P = .05) (Fig. 3A–C). There were trends toward significance in correlation of the shape abnormalities of the left CA1 and CA2–4+DG with immediate visual memory performance (r = −0.31, P = .08; r = −0.33, P = .06; respectively) (Fig. 3F,H). There was no correlation between hippocampal volume and immediate visual memory scores. No significant correlations were observed within the control group.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between hippocampal shape scores and visual memory (WMS-III Faces) performance within the PPA group. Shape scores that are more positive represent a hippocampal shape that deviates farther from the average control. (A–D) Correlation between hippocampal shape scores in the whole right hippocampus and its subfields and immediate visual memory (WMS-III faces: immediate scores) within the PPA group. (A) Whole hippocampal shape score vs. WMS-III faces immediate score (P < .01). (B) CA1 subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .01). (C) Subiculum subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .05). (D) CA2–4+DG subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .20). Declines in immediate visual memory performance were correlated with an increased shape deformity in the right whole hippocampus, CA1, and subiculum. (E–H) Correlation between hippocampal shape scores in the whole left hippocampus and its subfields and immediate visual memory (WMS-III Faces: immediate scores). (E) Whole hippocampal shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .99). (F) CA1 subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .08). (G) Subiculum subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .11). (H) CA2–4+DG subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Immediate score (P = .06). There were trends toward significance in the left CA1 and CA2–4+DG. (I–L) Correlation between hippocampal shape scores in the whole right hippocampus and its subfields and delayed visual memory (WMS-III Faces: Delay scores). (I) Whole hippocampal shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .10). (J) CA1 subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .25). (K) Subiculum subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .12). (L) CA2–4+DG subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .09). There were trends toward significance in the right whole hippocampus and CA2–4+DG. (M–P) Correlation between hippocampal shape scores in the whole left hippocampus and its subfields and delayed visual memory (WMS-III Faces: delay scores). (M) Whole hippocampal shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .77). (N) CA1 subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .03). (O) Subiculum subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .28). (P) CA2–4+DG subfield shape score vs. WMS-III Faces Delay score (P = .15). Declines in delayed visual memory performance were correlated with increased shape deformity in the left CA1. Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; WMS-III, Wechsler Memory Scale, Third Edition; CA2–4+DG, CA2, 3, 4 and dentate gyrus.

Lower delayed visual memory scores were correlated with the measure of increased shape deformity in the left CA1 (r = −0.38, P = .03) (Fig. 3N). There were trends toward significance in the correlation of shape of the right whole hippocampus and CA2–4+DG with reduced delayed visual memory (r = −0.30 P = .10; r = −0.31, P = .09; respectively) (Fig. 3I,L). There was no correlation between hippocampal volume and delayed visual memory scores. No significant correlations were observed within the control group.

3.4. ApoE genotyping

Of the 33 PPA patients in the present study with both ApoE genotyping and memory data, 21% (n = 7) had the AD risk factor allele, ε4. T-tests yielded no significant difference in memory scores between those with the allele present and absent [raw scores: immediate, t(31) = 1.2, P = .24; delay, t(31) = 0.7, P = .49; scaled scores: immediate, t(31) = 1.5, P = .15; delay, t(31) = 0.8, P = .40)] (Table 4). In fact, compared with normative data (WMS scaled scores), the three PPA patients in the study with mild impairment in memory all did not possess an ε4 allele, and those with an ε4 allele had average or better memory. T-tests on shape summary scores for the whole hippocampus and each subfield in both hemispheres yielded no significant differences between APOE ε4 present and absent groups (all P > .25).

Table 4.

ApoE genotyping in PPA

| ε4 allele absent, n = 26 (79%) | ε4 allele present, n = 7 (21%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ApoE allele | ε2/ε2 (1) ε3/ε3 (25) | ε3/ε4 (6) ε4/ε4 (1) |

| Mean (SD) (range) | ||

| Immediate Raw Score | 35.5 (5.1) [26–44] | 38.0 (4.5) [30–43] |

| Delay Raw Score | 37.0 (4.7) [28–45] | 38.3 (2.2) [35–41] |

| Immediate Scaled Score | 10.7 (3.1) [6–17] | 12.7 (3.1) [8–17] |

| Delay Scaled Score | 12.2 (3.5) [6–18] | 13.4 (2.2) [11–17] |

Abbreviations: ApoE, apolipoprotein ε; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Post-mortem studies suggest a significant heterogeneity in the neuropathologic diagnosis associated with nonsemantic PPA, with 30% to 60% having atypically distributed AD pathology [4], [5], [6], [7]. For this study, we hypothesized that because AD pathology would be present in a portion of the patients studied, hippocampal changes would be variable, and some would share common features with those reported in typical amnestic forms of AD [12], [46]. In fact, compared with typical hippocampal patterns reported in studies of DAT [14], we found similarities, in the inward deformity of CA1 and subiculum, but also differences, in the outward deformity of CA2–4+DG.

The PPA patients showed asymmetry in a pattern of smaller left than right hippocampi that was not observed in the controls, and bilateral shape deformities that were more pronounced in the left hippocampus than the right compared with the controls. Moreover, the volume and shape asymmetry indicates that shape deformity in the left hippocampus is accompanied by volume loss, and abnormality of the left hippocampus is a consistent finding in previous PPA, studies [18], [20], [47], [48]. Furthermore, although there was no absolute episodic memory impairment, interindividual variations in delayed face recognition memory performance correlated with left CA1 shape measures in PPA, whereas variations in the immediate memory performance correlated with right whole hippocampal shape deformity. In both instances, increased shape deformity was correlated with worse episodic memory performance, and no such correlations were found in controls. These observed patterns in delayed memory are consistent with the known dominant role of the left hippocampus in all types of episodic memory, and the patterns for immediate memory are consistent with the role of the right temporal lobe in the working memory functions underlying face processing [32], [49]. Specifically, positron emission tomography of healthy subjects has revealed that although the right hippocampus is essential for face processing, the left is recruited during episodic memory judgments of face stimuli [49]. Furthermore, the imaging of healthy subjects making judgments on face stimuli revealed early right hippocampal involvement and gradually increasing left hippocampal involvement only with greater memory load or time interval [50], [51].

We also found that PPA patients with the ApoE ε4 allele did not show impaired memory or different hippocampal shape compared with PPA patients with other ApoE genotypes. A pattern of memory impairment and hippocampal atrophy consistent with amnestic dementia was not expected in the PPA patients with an ε4 allele, because the ε4 allele in this diagnostic group does not increase the accuracy of predicting underlying AD neuropathology [28]. Although post-mortem data were not available in this study, we would expect that the neuropathologic source of localized hippocampal changes in PPA may vary. In some PPA patients with AD pathology, the hippocampus may contain neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques that cause neuronal death and morphological distortion within the hippocampus [3]. In AD cases and in those with FTLD pathology, peak neurodegeneration sites in the PPA patients may encompass neocortical regions that project to the hippocampus. Prefrontal and temporal cortices in PPA patients have shown atrophy as the disease progresses [17]. Tracing studies of hippocampal connectivity in the rhesus monkey have revealed corresponding afferent and efferent cortical projections in the hippocampal formation, particularly throughout the CA1 and subicular subfields [52], [53]. Diffusion tensor imaging studies in PPA have also suggested damage to white matter tracts that project to atrophic cortical areas [54], [55]. The particular mechanism whereby cortical atrophy, white matter damage, and hippocampal CA1/subiculum deformity correspond has yet to be determined. Alterations of shape through Wallerian or transsynaptic mechanisms are potential explanations. Furthermore, although some studies have examined overall cortical and subcortical densities in aphasic and amnestic AD [3], [56], differences in the focal distribution of pathology among hippocampal subfields have yet to be determined. Therefore, future work in these areas will be integral to the understanding of hippocampal shape change in PPA.

The greater abnormality of the left hippocampus may reflect the asymmetrically greater degeneration of the language-dominant (usually left) hemisphere in PPA. Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, the resultant hippocampal abnormalities seem to have been functionally compensated because the patients on average did not evidence recognition memory impairments compared with healthy individuals. However, the morphological abnormalities were not inconsequential, because they were related to interindividual variations in performance on memory tasks. In the future such in vivo investigations can be combined with post-mortem or biomarker data concerning the underlying pathology, such as tau and amyloid PET imaging, to explore the cellular basis of hippocampal deformities and their functional impact.

Finally, our analysis indicated that although overall hippocampal volume could not distinguish PPA from controls, hippocampal shape measures revealed strong group differences in different subfields. This indicates that hippocampal subfield shape can be used as an in vivo marker of structural changes that are not reflected in volumetric measures in patients with PPA. Many of the individuals in this study have agreed to brain donation at the time of death, which will allow for the further validation of these findings.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: We reviewed the literature on in vivo neuroimaging findings on the hippocampus in nonsemantic primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Although the hippocampus has been well-studied in typical Alzheimer's disease (AD), detailed examinations have not been previously conducted for nonsemantic PPA.

-

2.

Interpretation: Hippocampal shape abnormalities in PPA showed both differences and similarities to the typical AD pattern. Furthermore, damage to hippocampal subregions that are related to memory impairment in typical AD is also related to the level of memory ability in PPA, despite the preserved functional memory of patients with PPA.

-

3.

Future directions: Combining our computational anatomy methods with cellular measures from post-mortem or biomarker data will advance our understanding of specific effects of the varied pathology in this disease. The use of statistical learning algorithms on imaging data will also allow for the examination of potential pathological subsets in PPA.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant titled Language in PPA (DC008552) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS; R01 NS075075) and by the Alzheimer Disease Core Center grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG13854) both at the Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center, and NIH grants R01 NR014182, P50 AG05681, P01 AG03991, P01 AG026276. The Northwestern PPA Research Program and Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine conducted clinical and cognitive examinations and collected neuroimaging data for all PPA and control subjects. Some atlas images were provided from work that was in part funded by the Alzheimer's Association: “A Harmonized Protocol for Hippocampal Volumetry: an EADC-ADNI Effort”, grant n. IIRG -10-174022; project PI Giovanni B Frisoni, IRCCS Fatebenefratelli, Brescia, Italy; co-PI Clifford R. Jack, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. We would like to thank Ashley Chong and Hande Ozergin for discussions on manual editing procedures.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Mr. Christensen: None, Ms. Alpert: None, Dr. Rogalski: NIH grant during the course of the study DC008552, R01 NS075075, Dr. Cobia: None, Dr. Rao: None, Dr. Beg: None, Dr. Weintraub: NIH grant during the course of the study DC008552, R01 NS075075, AG13854, Dr. Mesulam: None, Dr. Wang: None.

References

- 1.Mesulam M.M. Primary progressive aphasia—a language-based dementia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1535–1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorno-Tempini M.L., Hillis A.E., Weintraub S., Kertesz A., Mendez M., Cappa S.F. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76:1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gefen T., Gasho K., Rademaker A., Lalehzari M., Weintraub S., Rogalski E. Clinically concordant variations of Alzheimer pathology in aphasic versus amnestic dementia. Brain. 2012;135:1554–1565. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam M., Wicklund A., Johnson N., Rogalski E., Leger G.C., Rademaker A. Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:709–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alladi S., Xuereb J., Bak T., Nestor P., Knibb J., Patterson K. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2007;130:2636–2645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu W.T., McMillan C., Libon D., Leight S., Forman M., Lee V.M. Multimodal predictors for Alzheimer disease in nonfluent primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2010;75:595–602. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ed9c52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knibb J.A., Xuereb J.H., Patterson K., Hodges J.R. Clinical and pathological characterization of progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:156–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorno-Tempini M.L., Brambati S.M., Ginex V., Ogar J., Dronkers N.F., Marcone A. The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2008;71:1227–1234. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000320506.79811.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyman B.T., Vanhoesen G.W., Damasio A.R., Barnes C.L. Alzheimers-disease-cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal-formation. Science. 1984;225:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.6474172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H., Braak E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1996;165:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apostolova L.G., Morra J.H., Green A.E., Hwang K.S., Avedissian C., Woo E. Automated 3D mapping of baseline and 12-month associations between three verbal memory measures and hippocampal atrophy in 490 ADNI subjects. Neuroimage. 2010;51:488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L., Miller J.P., Gado M.H., McKeel D.W., Rothermich M., Miller M.I. Abnormalities of hippocampal surface structure in very mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuroimage. 2006;30:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price J.L., Morris J.C. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Csernansky J.G., Hamstra J., Wang L., McKeel D., Price J.L., Gado M. Correlations between antemortem hippocampal volume and postmortem neuropathology in AD subjects. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price J.L., Ko A.I., Wade M.J., Tsou S.K., McKeel D.W., Morris J.C. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1395–1402. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillozet A.L., Weintraub S., Mash D.C., Mesulam M.M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:729–736. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogalski E., Cobia D., Harrison T.M., Wieneke C., Weintraub S., Mesulam M.M. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2011;76:1804–1810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Pol L.A., Hensel A., van der Flier W.M., Visser P.J., Pijnenburg Y.A., Barkhof F. Hippocampal atrophy on MRI in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:439–442. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.075341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorno-Tempini M.L., Dronkers N.F., Rankin K.P., Ogar J.M., Phengrasamy L., Rosen H.J. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:335–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindberg O., Walterfang M., Looi J.C., Malykhin N., Ostberg P., Zandbelt B. Hippocampal shape analysis in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:355–365. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan A.R., Wang L., Beg M.F. Multistructure large deformation diffeomorphic brain registration. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60:544–553. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2230262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L., Khan A., Csernansky J.G., Fischl B., Miller M.I., Morris J.C. Fully-automated, multi-stage hippocampus mapping in very mild Alzheimer disease. Hippocampus. 2009;19:541–548. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beg M.F., Miller M.I., Trouve A., Younes L. Computing large deformation metric mappings via geodesic flows of diffeomorphisms. Int J Comp Vision. 2005;61:139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aljabar P., Heckemann R.A., Hammers A., Hajnal J.V., Rueckert D. Multi-atlas based segmentation of brain images: atlas selection and its effect on accuracy. Neuroimage. 2009;46:726–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. Wechsler Memory Scale. Third edition. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown C., Lloyd-Jones T.J. Beneficial effects of verbalization and visual distinctiveness on remembering and knowing faces. Mem Cognit. 2006;34:277–286. doi: 10.3758/bf03193406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weintraub S., Rogalski E., Shaw E., Sawlani S., Rademaker A., Wieneke C. Verbal and nonverbal memory in primary progressive aphasia: the Three Words-Three Shapes Test. Behav Neurol. 2013;26:67–76. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2012-110239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogalski E.J., Rademaker A., Harrison T.M., Helenowski I., Johnson N., Bigio E. ApoE E4 is a susceptibility factor in amnestic but not aphasic dementias. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:159–163. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318201f249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weintraub S., Salmon D., Mercaldo N., Ferris S., Graff-Radford N.R., Chui H. The Alzheimer's Disease Centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kertesz A. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1982. Western aphasia battery. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller L.A., Lai R., Munoz D.G. Contributions of the entorhinal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus to human memory. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:1247–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelley W.M., Miezin F.M., McDermott K.B., Buckner R.L., Raichle M.E., Cohen N.J. Hemispheric specialization in human dorsal frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe for verbal and nonverbal memory encoding. Neuron. 1998;20:927–936. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogalski E., Cobia D., Harrison T.M., Wieneke C., Thompson C.K., Weintraub S. Anatomy of language impairments in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3344–3350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5544-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haller J.W., Banerjee A., Christensen G.E., Gado M., Joshi S., Miller M.I. Three-dimensional hippocampal MR morphometry with high-dimensional transformation of a neuroanatomic atlas. Radiology. 1997;202:504–510. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boccardi M., Bocchetta M., Ganzola R., Robitaille N., Redolfi A., Duchesne S. Operationalizing protocol differences for EADC-ADNI manual hippocampal segmentation. Alzheimer Dement. 2015;11:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sachdev P.S., Brodaty H., Reppermund S., Kochan N.A., Trollor J.N., Draper B. The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study (MAS): methodology and baseline medical and neuropsychiatric characteristics of an elderly epidemiological non-demented cohort of Australians aged 70–90 years. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:1248–1264. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu A., Miller M.I. Multi-structure network shape analysis via normal surface momentum maps. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1430–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Csernansky J.G., Wang L., Joshi S., Miller J.P., Gado M., Kido D. Early DAT is distinguished from aging by high-dimensional mapping of the hippocampus. Dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology. 2000;55:1636–1643. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Styner M., Oguz I., Xu S., Brechbuhler C., Pantazis D., Levitt J.J. Framework for the Statistical Shape Analysis of Brain Structures using SPHARM-PDM. Insight J. 2006:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L., Swank J.S., Glick I.E., Gado M.H., Miller M.I., Morris J.C. Changes in hippocampal volume and shape across time distinguish dementia of the Alzheimer type from healthy aging. Neuroimage. 2003;20:667–682. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duvernoy H.M. J.F. Bergmann; München: 1988. The human hippocampus: an atlas of applied anatomy. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Csernansky J.G., Wang L., Swank J., Miller J.P., Gado M., McKeel D. Preclinical detection of Alzheimer's disease: hippocampal shape and volume predict dementia onset in the elderly. Neuroimage. 2005;25:783–792. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.IBM . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bender R., Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shewan C.M., Kertesz A. Reliability and validity characteristics of the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) J Speech Hear Disord. 1980;45:308–324. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4503.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apostolova L.G., Dinov I.D., Dutton R.A., Hayashi K.M., Toga A.W., Cummings J.L. 3D comparison of hippocampal atrophy in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006;129:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohrer J.D., Ridgway G.R., Crutch S.J., Hailstone J., Goll J.C., Clarkson M.J. Progressive logopenic/phonological aphasia: erosion of the language network. Neuroimage. 2010;49:984–993. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seeley W.W., Matthews B.R., Crawford R.K., Gorno-Tempini M.L., Foti D., Mackenzie I.R. Unravelling Bolero: progressive aphasia, transmodal creativity and the right posterior neocortex. Brain. 2008;131:39–49. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kapur N., Friston K.J., Young a, Frith C.D., Frackowiak R.S.J. Activation of human hippocampal formation during memory for faces: a PET Study. Cortex. 1995;31:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paller K.A., Ranganath C., Gonsalves B., LaBar K.S., Parrish T.B., Gitelman D.R. Neural correlates of person recognition. Learn Mem. 2003;10:253–260. doi: 10.1101/lm.57403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McIntosh A.R., Grady C.L., Haxby J.V., Ungerleider L.G., Horwitz B. Changes in limbic and prefrontal functional interactions in a working memory task for faces. Cerebral Cortex. 1996;6:571–584. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blatt G.J., Rosene D.L. Organization of direct hippocampal efferent projections to the cerebral cortex of the rhesus monkey: projections from CA1, prosubiculum, and subiculum to the temporal lobe. J Comp Neurol. 1998;392:92–114. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980302)392:1<92::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbas H., Blatt G.J. Topographically specific hippocampal projections target functionally distinct prefrontal areas in the rhesus monkey. Hippocampus. 1995;5:511–533. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y., Tartaglia M.C., Schuff N., Chiang G.C., Ching C., Rosen H.J. MRI signatures of brain macrostructural atrophy and microstructural degradation in frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:431–444. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catani M., Mesulam M.M., Jakobsen E., Malik F., Martersteck A., Wieneke C. A novel frontal pathway underlies verbal fluency in primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2013;136:2619–2628. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Josephs K.A., Dickson D.W., Murray M.E., Senjem M.L., Parisi J.E., Petersen R.C. Quantitative neurofibrillary tangle density and brain volumetric MRI analyses in Alzheimer's disease presenting as logopenic progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2013;127:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]