Abstract

Background:

Traditional medicine (TM) has maintained its popularity in all regions of the developing world. Even though, the wide acceptance of TM is a well-established fact, its status in a population with access to modern health is not well clear in the whole country. This study was carried out to assess the knowledge, attitudes, practice and management of TM among the community of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia.

Methodology:

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on a total of 282 sampled individuals’ selected using systematic random sampling from January 28, 2013 to February 8, 2013 in Burka Jato Kebele, Nekemte town, East Wollega Zone, West of Ethiopia.

Results:

The majority (94.22%) of people in the study area relied on TM. Most of them were aware of medicinal herbs (55.7%). About half (40.79%) of the respondents were aware of the major side-effects of TM such as diarrhea (36.64%). About 31.85% of them prefer traditional medical practices (TMP) because they are cheap. Most (50%) of the species were harvested for their leaves to prepare remedies, followed by seed (21.15%) and root (13.46%) and the methods of preparation were pounding (27.54%), crushing (18.84%), a concoction (15.95%) and squeezing (13.04%). About 53.84% of them were used as fresh preparations. Remedies were reported to be administered through oral (53.85%), dermal or topical (36.54%), buccal (3.85%) and anal (5.77%).

Conclusion:

The study revealed that the use of TMs were quite popular among the population and a large proportion of the respondents not only preferred, but also used TMs notwithstanding that they lived in the urban communities with better access to modern medical care and medical practitioners. To use TM as a valuable alternative to conventional western medicine, further investigation must be undertaken to determine the validity, efficacy of the plants to make it available as an alternative medicine to human beings.

KEY WORDS: Attitude, knowledge, management, practice, traditional medicine

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines traditional medicine (TM) as health practices, approaches, knowledge and beliefs incorporating plant, animal and mineral based medicines, spiritual therapies, manual techniques and exercises, applied singularly or in combination to treat, diagnose and prevent illnesses and maintain well-being. In Africa, up to 80% of the population uses TM for primary health care. For example TM is used in Ghana, Mali, Nigeria and Zambia, widely widely for the treatment of fever resulting from malaria. One-third of the population in developing countries lack access to essential medicines, and traditional birth attendants(TBAs) are commonly assisting in many African countries.[1]

There are widespread systems of traditional and complementary medicine, which includes Ayurvedic medicine in South Asia, especially in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Srilanka. In china, traditional herbal preparations account for 30-50% of total medicinal consumption.[2]

Traditional medicine in Ethiopia is characterized by historical developments related to prolonged immigrations from the southern Arabian Peninsula, the influence of Green culture, and the introduction of Christianity and Islam.[3] Most traditional medical practitioners (TMPs) in Ethiopia rely on an explanation of disease that draws on both the “mystical” and “natural” causes of illness and employ a holistic approach to treatment.[4] Despite western medicine becoming more widespread in Ethiopia, Ethiopians tend to rely more on TM.[5]

Due to poor access to health services, especially in the rural areas the majority of the Ethiopian people use TM due to the cultural acceptability of healers, local pharmacopoeias, the relatively low cost of TM and difficult access to modern health facilities. In 2000, only 9.45% of all deliveries in Ethiopia were attended by trained attendants and health worker. The rest was attended by traditional birth attendants or relatives.[6,7]

The vast majority of Ethiopians live in rural areas where the health care coverage is low and one of the greatest challenges faced by the country is determining how best to narrow the gap between the existing services and the population has access to them is very limited.[8,9] The progress made so far in this direction in other countries has allowed for a wide utilization of TM and better recognition of its practitioners as heritage benefiting the majority of their people.[10] In Ethiopia, a number of harmful practices have been traced to healers, including female genital mutilation, uvelectomy and milk tooth extraction.[11]

In Ethiopia, a little has been done in recent decades to enhance and develop the beneficial aspects of TM including relevant research to explore possibilities for its gradual integration into modern medicine.[12] The Ethiopian people reliance on TM is also reflected by the fact that Ethiopian migrants in developed countries continue using them. For example, a number of herbs, traditional medical devices and traditional practitioners are available in the UK.[13] Ethiopian patients may feel that they will be judged by their physician if they disclose their use of TM.[9]

The main body of Ethiopian TM is based on the use of ethno botany. Some of the ailments that are ordinarily treated with medicinal plants include abscess, arthritis, ascariasis, burns, colds, constipation, diabetes, dysentery, eclampsia, gastritis, gonorrhea, heartburn, headache, hemorrhoids, hepatitis, herpes simplex, kwashiorkor, leprosy, malaria, measeals, rabies, rheumatism, scabies, syphilis, schistosomiasis, tinea and toothache.[3]

Many herbal substances that are used in Ethiopian traditional medicine are also used as ingredients and spices in Ethiopian food. Consumption of these herbs and spices as part of a normal diet is not likely to cause adverse herb-drug interactions because they are consumed in relatively small quantities. However, when these herbs and spices are utilized for medicinal purposes there may be an increased likelihood of adverse interactions with conventional medicines. There are several classes of medications that are at a higher risk for adverse herb-drug interactions, including anti-arrhythmic, anti-seizure, anti-diabetic, and anti-coagulant medication. Health care providers are particularly attuned to these interactions because these drugs are typically monitored with serum levels and serum markers (e.g., warfarin, digoxin). The risk is increased because of the chemical composition of these medicines and because they treat some of the most common illnesses in the Ethiopian immigrant population.[9]

In spite of the promulgation of the necessary policies, little has been done in recent decades to enhance and develop the beneficial aspects of TM including related research and its gradual integration into modern medicine.[6]

A good insight about traditional system of medicine is essential, especially in a country where people cannot afford over drug oriented system of modern health care. In the present study, knowledge, attitude, practice and management of TM in comparison to modern medicine (MM) and possible adverse interactions of TM and MM were assessed.

Methodology

Study area, period and population

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from January 28, 2013 to February 8, 2013 in Burka Jato Kebele, Nekemte town, East Wollega Zone, West Ethiopia, 330 km away from Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia. There are a total of 4,917 female and 4,515 male individuals in the kebele.

Sample size and sampling technique

A systematic random sampling technique was used. Sample interval was determined by dividing the total number of households by sample size and select the first study unit using “Lottery” method.

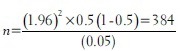

The sample size was determined using the formula:

Hence,

n = 384, n = minimum sample size

Where; n = desired sample size from the population

Z = Confidence interval, 95% =1.96

P = Population prevalence = 0.5

Q = 1 − p = 1–0.5 = 0.5

D = Degree of accuracy desired at 0.05

Since the number of the population was less than 10,000 (9,432) and number of households was calculated to be 1070. A convenience sample of 282 individuals (households) was selected from the community by systematic random sampling.

Data collection, quality control, analysis and interpretation

Data were collected by two persons, and the households were interviewed by using using both closed and open ended questionnaires. Data collectors were briefed on the objectives, relevance of the study, on terms and how to collect the data. The collected data was first checked for Completeness and analysis was performed both by computer and manually. Chi square test was used to determine the statistical significance of association between some variables. Results were analyzed, interpreted and presented in texts, tables and figures and they were discussed in comparison with some similar studies done before.

Ethical issues

Letter of permission was written from Jimma University, Pharmacy Department to the chairman of Burka Jato Kebele community and explanation about the objectives and use of the study was given to the community. Informed consent was taken from each person after explaining the purpose of the study. Respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The interviewers were advised to be as polite as possible and respect the response of the person.

Results

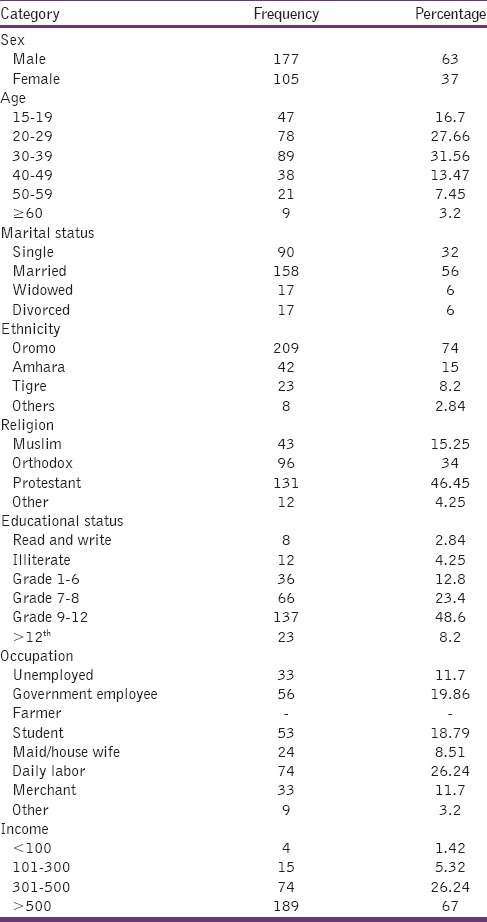

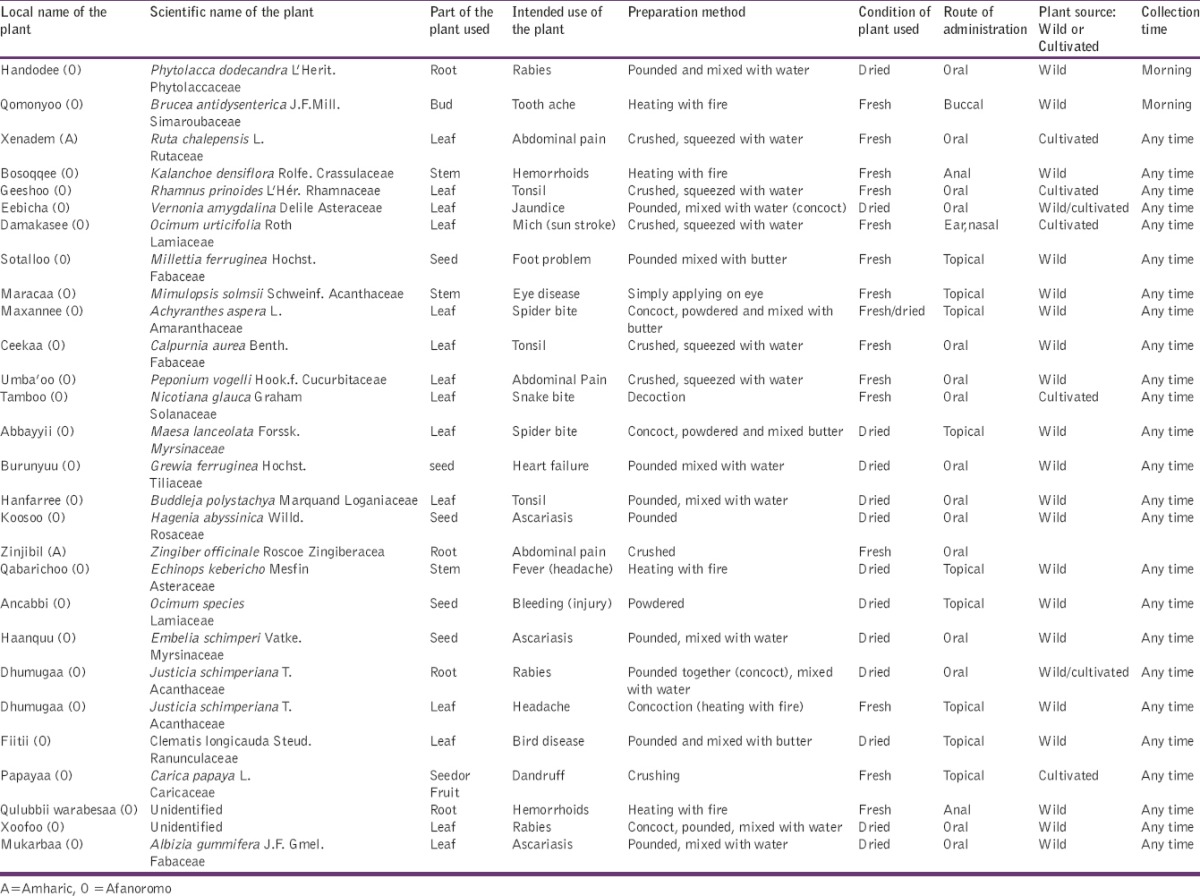

A total of 282 respondents participated in the study. Their mean age was 30 and the modal age group was 33 (30–39). Almost all of the respondents are living in an urban area. The sex ratio was predominated by male (63%) and the majority was found in the age group of 30–39 (31.56%). The majority of the population of the Kebele were protestant (46.45%). Oromo Took the highest ethnic group (74%), followed by Amhara (15%). A total of 52 medicinal plant species were identified among this 28 were documented [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of the study population by socio demographic and economic characteristics of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia, February 2013

More than half of the Burka Jato people (56%) were married, and majority of their educational status (48.6%) were between grade 9 and 12. More than quarter (26.24%) live by daily labor and 67% of people earn more than 500 Birr/month [Table 2].

Table 2.

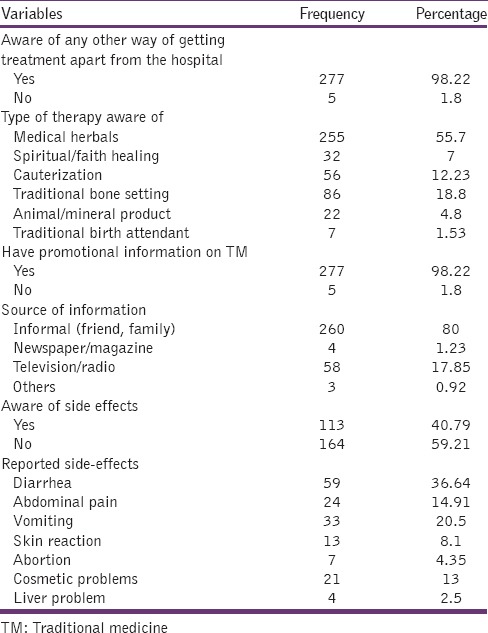

Knowledge of Burka Jato people towards TM, West Ethiopia, February 2013

Majority of Burka Jato Kebele people were aware of alternative treatment options apart from modern medicine (i.e., 98.22%). The type of TM known to the respondents were; medicinal herbs (55.7%), traditional bone setting (18.8%), cauterization (12.23%), spiritual or faith healing (7%), animal or mineral product (4.8%) and traditional birth attendant (1.53%).

The majority of the people got information from informal sources (family, friend, etc.,) 80%, followed by mass media (TV or Radio) 17.85% and newspaper or magazine 1.23%. About half of the respondents, 40.79% were aware of the major side-effects of TM, such as diarrhea (36.64%), vomiting (20.5%), abdominal pain (14.91%), and the remaining 59.21% were not aware of the side effects of TM [Table 3].

Table 3.

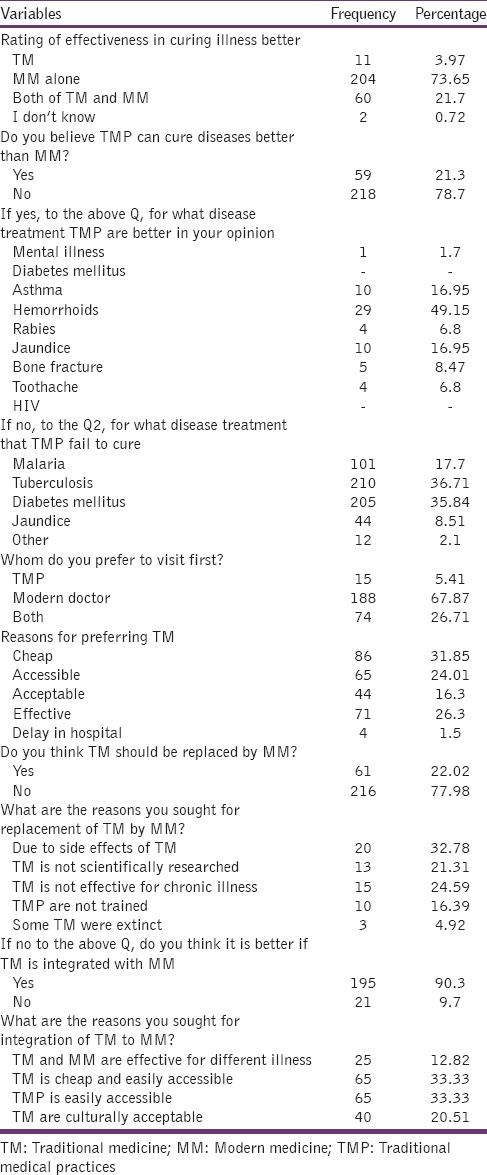

Attitude to TM therapy by the respondents of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia, February 2013

Based on the rate of curing illness; percentage of people who selected modern medicine were 73.65%, both modern and TM, 21.7%, TM alone 3.97% and those who did not know 0.72%. The majority of the respondents did not believe that TMPs could cure diseases better than (MM) 78.7% and the remaining 21.3% could believe that TM could cure illness better than MM: Such as; hemorrhoids 49.15%, asthma 16.95%, rabies 6.8%, jaundice 16.95%, bone fracture 8.47% and toothache 6.8%. About 67.87% of the respondents preferred a modern doctor, 26.71% both modern doctor and TMP and the remaining 5.41% prefer TMP.

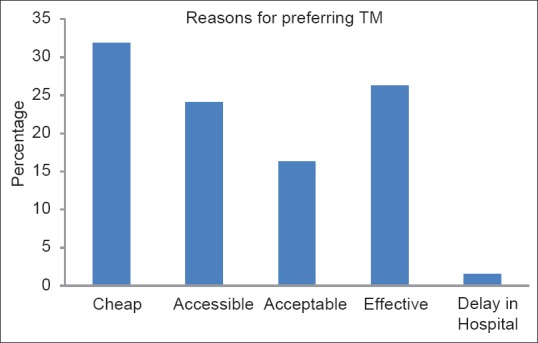

Figure 1 shows the various reasons of respondents for preferring TM to MM and they were: Cheap 31.85%, effective 26.3%, accessible 24.07%, acceptable 16.3% and delay in hospital 1.5%.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of respondents on reasons for preferring traditional medicine in Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia, February 2013

The percentage of respondents who suggest the TM should not be integrated with MM, but should be replaced by MM are; 9.7% and 22.02%, respectively. The percentage of respondents who suggest the TM should not replace by MM, but should be integrated are, 77.98% and 90.3% respectively [Table 4].

Table 4.

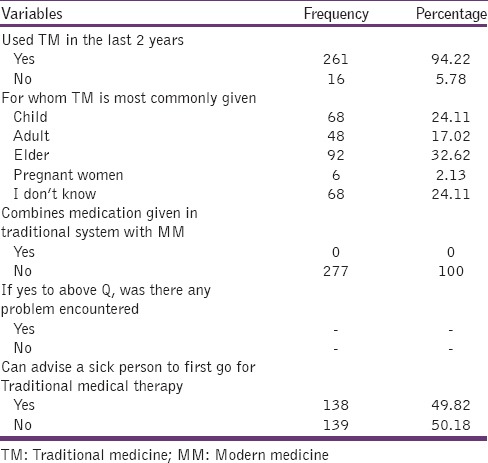

Practice of TM by Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia

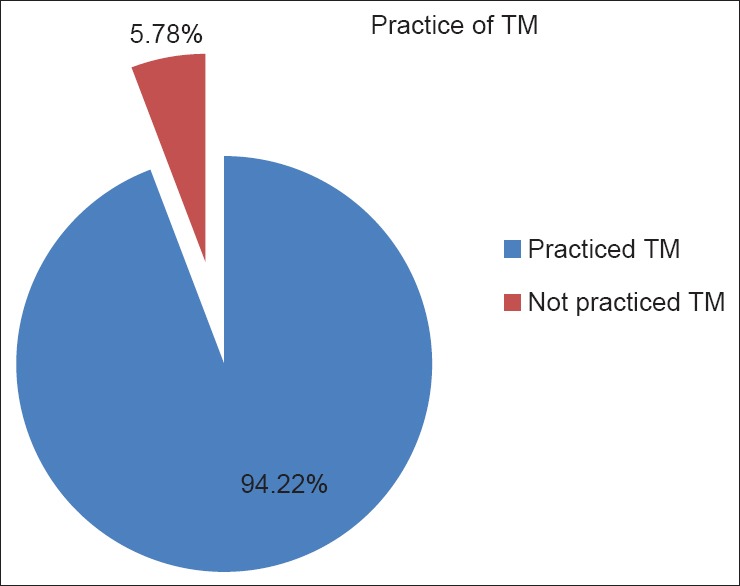

Majority of Burka Jato people 94.22% had practiced TM at least in the last 2 years and the remaining 5.78% did not practice TM which is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of respondents on practice of traditional medicine in Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia, February 2013

As shown in Table 4, TM was most commonly given to elder 32.62%, children 24.11%, adult 17.02%, pregnant women, 2.13% and the remaining 24.11% did not know for whom TM was most commonly given. Half of those people who practiced TM in the last 2 years, advised sick person to go first for TM 49.82% and the remaining 50.18% did not advice sick person to go first for TM.

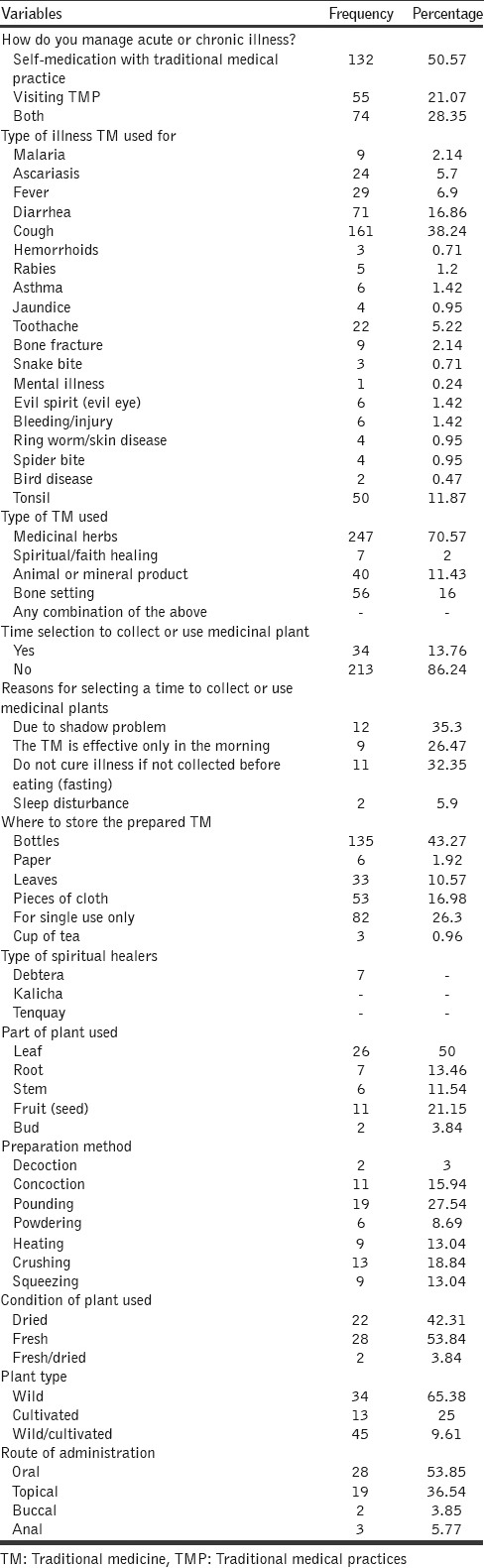

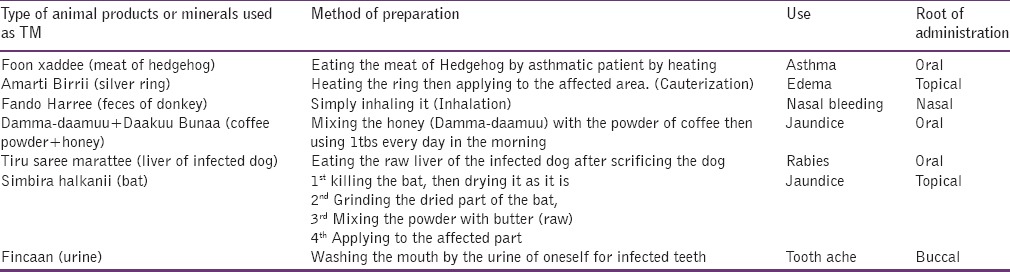

As depicted in Table 5 people who practiced TM in the last 2 years, those who manage acute or chronic illness by themselves (self-medication) were 50.57%, those who visited traditional healers 21.07% and those who practiced both (i.e. self-medication and visit TMP) were 28.35%. There were different type of illness that were managed by TM, among them cough 38.24% was the leading one. Type of TM used; medicinal herbs 70.57%, bone setting 16%, animal or mineral product 11.43% and spiritual faith healing 2%.

Table 5.

Management of TM by Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia

The majority of the people did not select time to collect or use TM accounts for 86.24% and the remaining 13.76% had time selection to collect or use TM. The containers where they store TM were: Bottles 43.27%, pieces of cloth 16.98%, leaves 10.57%, paper 1.92%, cup of tea 0.96% and the remaining 26.3% do not store it (i.e. for single use only).

Most of the species (50%) were harvested for their leaves to prepare remedies. Preparation of remedies from seed (21.15%) and root (13.46%). The principal methods of remedy preparation were reported through pounding (27.54%), crushing (18.84%), a concoction (15.95%) and squeezing (13.04%) of the various parts of medicinal plants. About 53.84% of the medicinal species were cited to be used in fresh forming remedy preparations. Relatively 42.31% medicinal plant species were reported to be used in dried form and 3.84% in fresh or dried. Remedies were reported to be administered through oral (53.85%), dermal or topical (36.54%), buccal (3.85%) and anal (5.77%) which are shown in Table 5.

Among the cited medicinal plant species of the study area, the majority (65.35%) were wild or cultivated. Whereas 25% of the reported medicinal plant species were cultivated. Few species, 9.61% were indicated as wild/cultivated.

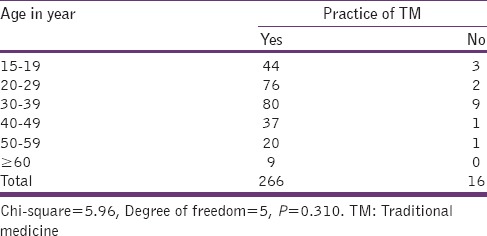

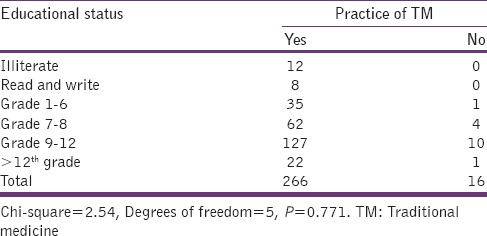

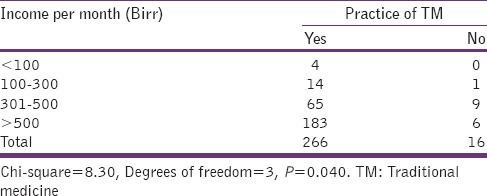

There was no relationship or association between respondents age, educational status and the practice of TM (Tables 6 and 7) respectively, as all tests of association were not statistically significant P > 0.05. However, there was association between income and practice of TM. As all tests of association was statistically significant P < 0.05 [Table 8]. This is because the majority of the people who practice TM, prefer it due to its cost (cheap: 31.85%), since TM is very cheap compared to modern medicine. About twenty eight different medicinal plants, six animal products and a mineral product were found to be used traditionally for treatment and/or management of various ailments by the study subjects in Burka Jato kebele, West Ethiopia [Tables 9 and 10].

Table 6.

Association between age and practice of TM

Table 7.

Association between educational status and practice of TM

Table 8.

Association between income and practice of TM

Table 9.

Herbal medicines used in traditional medicine among the people in Burka Jato kebele, West Ethiopia, Feburary 2013

Table 10.

Some animal products and minerals used in traditional medicine among the people in Burka Jato kebele, West Ethiopia, Feburary 2013

Discussion

Due to poor access to health services, especially in the rural areas, the majority of the Ethiopian people rely mainly on TM for the system of their primary health care needs.[6] As there is no adequate study done in Burka Jato Kebele and also in other regional Kebeles in Ethiopia, regarding TM knowledge, practice, management as well as their attitudes, it is hoped that findings from this study will also initiate different stake holders to get involved in this area and it will be helpful as a baseline for other studies that will be conducted in the future. It will be of great importance to plan for control measures against any health hazards from abuse of alternative medical therapy. Therefore, it would be of important value to assess the knowledge, attitude, practice and management of TM among the community. TM and associated knowledge in the study area, one of the alternatives for the solution of health problem, rises in a large segment of the rural population are employing TM in general and medicinal plant in particular. However, documentation of this indigenous knowledge of healing system still remains at minimum level. Similar observations have also reported in research done by Zein and Kloos.[3]

The present study reported that the majority 98.22% of the respondents were aware of an alternative way of getting treatment for their ailments apart from modern medicine. The forms of alternative medical therapies (AMT) respondents were aware of include; medicinal herbs (55.7%), and traditional bone settings (18.8%) among others similar to the research conducted in Nigeria; 90.4% of the respondents were aware of alternative way of getting treatment, medicinal herbs and traditional bone settings were common among other forms of AMT.[14] The major source of information regarding TM were through: Informal sources (friends, family) 80%, which was higher than the research done at Arsi Zone (56.2%), East Ethiopia,[15] this might be due to lack of documentation or written standards and information concerning TM as it was transmitted orally from generation to generation. About 40.79% of the respondents were aware of the side effects from TM and these include diarrhea (36.67%), vomiting (20.5%) and abdominal pain (14.91%), which is similar to the research conducted in Nigeria, where 54.9% of the respondents were aware of side effects, diarrhea 69.7%, vomiting 40.2% and abdominal pain 42.2%.[15]

Only 3.97% of all the respondents who were aware of AMT believed that it could cure all forms of illness better than modern medicine (73.65%) and the remaining 21.7% respondents believed in both traditional and modern medicine. This is slightly lower than the research conducted in Nigeria, about 42% of all respondents believed in AMT.[14] The respondents’ fear of TM might be due to its side effects. Notwithstanding their knowledge of side effects and injuries from TM, about 21.3% of the respondents preferred TM to modern medicine which is similar to the research reported by Elujoba et al. about 35.7% prefer TM.[16] The reasons for preference of TM might be it is; cheap (31.85%), effective (26.3%), accessible (24.07%), acceptable (16.3%) and delay in hospital (1.5%). This is similar to the research conducted in Nigeria; cheap (21.4%), accessible (16.4%) and acceptable (13.4%).[14] More than half (77.98%) of respondents do not prefer a replacement of TM by modern medicine. Among this 90.3% prefer the integration of TM to modern medicine which correlates to the research done at Arsi Zone (East Ethiopia), 83.8% of the people are advocating for integration of TM into the modern medicine.[15]

The percentage of respondents who practiced TM in the last 2 years was, 94.22%, which correlates to the research reported by WHO, where 80% Ethiopian people practice or use TM.[2] Half of those respondents who practiced TM (49.82%), advised sick people to go to first for traditional medical practitioners which is higher than the research reported by Elujoba et al.: Only 28.7% advice traditional medical practitioners.[16] This might be because TM is intricately interwoven with the culture, socioeconomic and social cultural heritages of the respondents.

The ailments most commonly managed by the respondents were cough (38.24%) and diarrhea (16.86%) among others. This is similar to the research reported in Bench ethnic group (South West Ethiopia) by Giday et al., about 14% of the respondents used TM for the treatment of GIT problems.[17]

The local community mostly used leaves (50%) for the preparation of remedies and the root takes the second proportion 13.46%. Certain ethno botanical research in another part of the country reported similar result leaves (64.52%) followed by roots (19.35%), to be mostly used in the treatment of various health problems.[18] The majority of the harvested medicinal plants (65.38%) were wild, which is correlated to the research reported in Bench ethnic group by Giday et al., 86%.[17] About 53.84% of the medicinal plant species were cited to be used in fresh form for remedy preparations and followed by dried (42.31%), which correlates to the research reported by Yineger and Yewhalaw, where 64.52% of the medicinal plant species were in fresh form.[18] Oral and topical (dermal) were the major routes of administration of plant remedies. Accordingly 53.85% of the preparations were taken orally followed by topical or dermal (36.54%). Similarly Yirga and Zeraburk, have reported oral route (67.3%) and topical (30.6%) of application. Traditional medicinal plants were harvested mainly for their leaves and roots.[13]

A study conducted in Bench ethnic group indicated that some TM were used against the following eight human ailments: Gastro-intestinal complaints (14%), ear diseases (11%), deformation of fingers (9%), inflammation (6%), toothache (6%) rheumatic pain (3%), rabies (3%) and jaundice (3%). The majority (86%) of medicinal plants used by Bench ethnic group were uncultivated species, most of them were weeds and abundantly growing in disturbed habitats, mainly in crop fields, fallow lands and along hedgerows.[17]

A cross-sectional study conducted in Arsi Zone indicated that the local community acquired knowledge about TM from relatives accounted for (56.2%), traditional healers (30%), by themselves (3.7%), religious books (2.5%).Those who obtained knowledge from their relatives, expressed willingness to convey their knowledge, and preferred modern medicine accounted for 56.2%, 78.7% and 77.5%, respectively. According to this study, 83.8% of respondents supported the integration of TM with modern health service system and the remaining 12.3% did not support and few (3.8%) had no opinion.[15]

Conclusion

This study revealed that the use of TM is quite popular among the respondents and a large proportion of them not only preferred but also used TM not withstanding that they live around urban communities with better access to modern medical care and medical practitioners. Since safety and efficacy of the remedies used in TM remain largely unknown and untested to have met the gold standard therapy, advising patients and the general public who use or seek TM presents a professional challenge. Furthermore, local leaders, government and other stake holders in the sector should regulate the activities of the alternative medical therapists or practitioners and find a way of fully integrating their practices into the modern medicine. Regulations should be made concerning the advertisement of alternative medicine and practices since appropriate diagnosis were usually not made for the use of these drugs and respondents were usually not aware of the requirements.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vol. 5. Geneva: WHO; 2001. WHO. Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: A World Wide Review; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: WHO Media Center; 2003. WHO. Traditional Medicine. Fact sheet number. 134. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zein A, Kloos H. The ecology of health and diseases in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. J Bio Soc Sci. 2008;21:507–808. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishaw M. Promoting traditional medicine in Ethiopia: A brief historical review of government policy. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90180-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papadopoulos R, Lay M, Gebrehiwot A. Cultural snapshots: A guide to Ethiopian refuges for health care workers. Research center for trans cultural studies in health, Middlesex University, London UK N 14 4YZ; May. 2002. [Last accessed in June 2013]. Available from: http://www.max.ac.uk/www/rctsh/embrace.htm .

- 6.Washington, DC: © World Bank; [Last accessed in June 2014]. World Bank. 2001. Ethiopia-Traditional Medicine and the Bridge to Better Health. Available from: https://www.openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/10803 . License: CC BY 3.0 Unported. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Central Statistical Authority, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and ORC Macro, Calverton, Maryland, USA; May. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Transitional Government of Ethiopia Health Sector Strategy. Addis Ababa; April. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gall A, Shunkute Z. Ethiopian Traditional and Herbal Medications and their Interaction with Conventional Drugs. 2009. [Last accessed in June 2014]. Available from: http://www.ethnomed.org/clinical/pharmacy/ethiopian-herb-drug-interactions .

- 10.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1985. WHO. The Role of Traditional Medicine in Primary Health Care in China. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee on Traditional Practices of Ethiopia, Project Report; Baseline Survey on Harmful Traditional Practice in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Feb. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kebede DK, Alemayehu A, Binyam G, Yunis M. A historical overview of traditional medicine practices and policy in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20:127–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yirga G, Zeraburk S. Ethno botanical study of traditional medicinal plants in Gindeberet district, west Ethiopia. IJREISS. 2012;1:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamidele JO, Adebimpe WO, Oladele EA. Knowledge, attitude and use of alternative medical therapy amongst urban residents of Osun State, southwestern Nigeria. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2009;6:281–8. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v6i3.57175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Getachaw A, Dawit A, Timotewos G, Kalbessa U. Perceptions and practices of modern and traditional health practitioners about traditional health practitioners about traditional medicine in Shirka district, Arsi Zone Ethiopia. Ethiop Health Nutr Res Inst. 2002;16:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elujoba AA, Odeleye OM, Ogunyemi CM. Traditional medicinal development for medical and dental primary health care delivery system in Africa. Afr. J. Trad. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2005;2:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giday M, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z, Teklehaymanot T. Medicinal plant knowledge of the Bench ethnic group of Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical investigation. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:34. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yineger H, Yewhalaw D. Traditional medicinal plant knowledge and use by local healers in Sekoru District, Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]