Abstract

Background:

In diabetic populations, endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products (esRAGE) levels may be related to the degree of diabetic complications or to the protection from diabetic complications.

Objective:

We investigated the impact of 29 methanolic extracts from edible plants on esRAGE production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) cultured in high (4.5 g/L) glucose.

Materials and Methods:

Edible plants were minced, and extracts were obtained with methanol overnight. The methanolic extracts from 29 edible plants were evaporated in a vacuum. For screening study purposes, HUVECs were seeded in culture dishes (1.5 × 105 cells). Then, HUVECs were incubated with 1 g/L or 4.5 g/L of glucose in SFM CS-C medium treated with methanolic extracts from edible plants (MEEP) for 96 h. Determination of esRAGE production in the cell culture-derived supernatants was performed by colorimetric ELISA. The 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) level was determined by using the 8-OHdG Check ELISA kit. Peroxynitrite-dependent oxidation of 2’, 7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein to 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescein was estimated based on the method described by Crow. Because MEEP were methanolic extracts, we measured their total phenolic content (TPC). TPC was measured with a modified version of the Folin–Ciocalteu method.

Results:

The results showed eight extracts increased esRAGE production. The extract from white radish sprouts showed the highest esRAGE production activity, and then eggplant, carrot peel, young sweet corn, Jew's marrow, broad bean, Japanese radish and cauliflower. In order to understand the mechanism of esRAGE production, the eight extracts were examined for DNA damage, peroxynitrite scavenging activity, and TPC in correlation with their esRAGE production. The results showed esRAGE production correlates with the peroxynitrite level and TPC.

Conclusion:

This study supports the utilization of these eight extracts in folk medicine for improved treatment of diabetic complications.

KEY WORDS: 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, advanced glycation end products, edible plants, endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products, peroxynitrite radical scavenging activity, total phenolic content

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and a multiligand receptor for the late products of nonenzymatic glycation (advanced glycation end products [AGEs]). RAGE is also known to be involved in microvascular complications in diabetes through oxidative stress generation, regulation of atherogenesis, the angiogenic response, and vascular injury.[1,2,3] Numerous truncated forms of RAGE have been reported, and the C-terminally truncated soluble form of RAGE (sRAGE) has received much attention. Yonekura et al.[4] found that human vascular cells expressed a novel splice variant coding for an sRAGE protein and named it endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products (esRAGE). The esRAGE neutralizes AGE action on endothelial cells. In fact, RAGE antagonists are in clinical development as therapeutics for diabetes complications. Interfering with the activation of RAGE, using sRAGE, has been shown to prevent or ameliorate the vascular complications in experimental studies.[5] Furthermore, in diabetic populations, sRAGE and esRAGE levels may be related to the degree of diabetic complications or to the protection from diabetic complications. Indeed, Ramasamy et al.[6] first tested sRAGE as a ligand decoy and showed that administration of sRAGE to diabetic animals was at least partially protective against macro- and micro-vascular complications of diabetes. There is the following study about similar diabetic patients. Piarulli et al.[7] conducted to examine the relationship between esRAGE and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM) patients with/without advanced macro-angiopathy. They showed that the study established a relationship between esRAGE and oxidative stress and/or antioxidant power, suggesting that esRAGE upregulation might be part of the cell's antioxidative defenses against plaque forming as a result of oxidative stress in the T2DM phenotype. An important question to address, therefore, is the usefulness of circulating sRAGE and esRAGE as potential biomarkers of diabetic complications and need for therapy. However, relatively little is known about factors (thiazolidinedione,[8] atorvastatin,[9] and insulin[10]) that influence esRAGE production.

The potential beneficial roles of dietary antioxidants have been emphasized in treatment of various diseases including diabetes. Plant and plant-derived products in foods contain antioxidants that are thought to provide health benefits in decreasing the risk of disease. Extensive studies have been focused on the positive role of plant polyphenols as free radical scavengers and in disease prevention.[11,12] Polyphenols such as (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and genistein have been reported to possess therapeutic effects for obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.[13] Lee and Lee[14] investigated the protective effects of EGCG against AGEs-induced damage in neuron cells. The results showed that EGCG was found to down-regulate the mRNA level of RAGE in cells. On the other hand, Jung et al.[15] indicated that genistein disrupted AGE-RAGE binding and showed genistein exerted inhibitory effects on AGE formation in vitro.

No study has examined phenolic compound influence on esRAGE. However, because methanolic extracts from edible plants (MEEP) were methanolic extracts, we measured their total phenolic content (TPC). Some reports show esRAGE and RAGE to be related to guanosine in DNA[16,17] and peroxynitrite radicals.[18] Therefore, we examined the correlation between esRAGE production and the three indicators mentioned above to determine the mechanism for increasing esRAGE production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with eight plant extracts.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of methanolic extracts from 29 edible plants

Edible plants were purchased from an outdoor market, and then shelled or peeled. Edible plants (100 g) were minced into 5 mm fragments and extracts were obtained with methanol (200 mL) overnight at room temperature. The extracts were filtered and the residue was re-extracted under the same conditions as above. The combined filtrates were evaporated in a vacuum slightly below 40°C in a rotary evaporator. MEEP were prepared as a solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The specimen was dissolved in DMSO (1.0 mL).

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (No. JCRB0408, Health Science Research Resources Bank, Osaka, Japan) were cultured at 37°C in SFM CS-C medium (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 1.5 g/mL Fungizone under air-CO2 (95:5) (referred to hereafter as CS-CF medium). For screening study purposes, HUVECs were seeded in 60 mm culture dishes (1.5 × 105 cells). Then, HUVECs were incubated with 1 g/L (normal glucose medium) or 4.5 g/L (high glucose medium) of glucose in CS-CF medium treated with MEEP for 96 h. Two groups of experiments were formed, one receiving 1) continuous 10 μL MEEP, and the other receiving 2) continuous 100 μL MEEP.

Measurement of endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products concentrations in culture media

Determination of esRAGE production in the cell culture-derived supernatants was performed by colorimetric ELISA under the manufacturer's protocol (B-Bridge International, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Supernatants cultured with each sample were added to ELISA plates to measure the esRAGE content. Plates were analyzed at A450nm.

Measurement of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in human umbilical vein endothelial cells DNA

DNA of HUVECs was extracted from the homogenates using a DNA Extractor WB kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) according to the protocol. The 8-OHdG level was determined by using the 8-OHdG Check ELISA kit (Japan Institute for the Control of Aging, Shizuoka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A450nm was measured using a microplate reader. The recovery rate of 8-OHdG level was expressed as % recovery of the normal glucose medium A450nm (experimental A450nm/normal glucose medium A450nm × 100).

Measurement of peroxynitrite level

Peroxynitrite-dependent oxidation of 2,7- dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCDHF) to 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was estimated based on the method described by Crow.[19] Samples or control (DMSO) were added to 100 mM PBS (pH 7.4) containing 100 μM diethylenetriamine-N, N, N’, N”, N”-pentaacetic acid (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Japan), 5 μM sodium peroxynitrite and 100 μM DCDHF. The mixture was then incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The absorbance was measured at 500 nm, which is the absorbance of DCF. The peroxynitrite scavenging activity was expressed as % inhibition of the control A500nm ([control A500nm − experimental A500nm]/control A500nm × 100).

Determination of total phenolic content in methanolic extracts from edible plants

Because MEEP were methanolic extracts, we measured their TPC. TPC was measured with a modified version of the Folin–Ciocalteu method[20] using chlorogenic acid as a standard. Briefly, 100 μL of the sample or standard were combined with 200 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 2.0 mL of 2% Na2CO3 solution. We allowed the mixture to sit for 60 min before reading absorbance at 750 nm using a UV-460 spectrophotometer (Nihonbunko Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The concentration of TPC present in MEEP was determined by comparing it with the absorbance rates of standard chlorogenic acid at different concentrations.

Statistical analysis

We present all data as mean ± standard deviation. A statistical comparison between the groups was carried out using either ANOVA or Student's t-test. P <0.10 were considered as statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Effects of methanolic extracts from edible plants on endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production in high glucose-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells

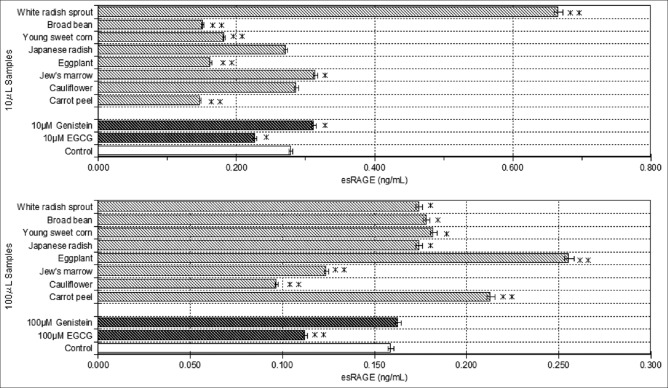

We examined the esRAGE-producing ability of 29 MEEP in high glucose-induced HUVECs. The result showed an increase in esRAGE production in the following gight samples (eggplant [Solanum melongena], carrot peel [Daucus carota subsp. sativus], young sweet corn [Zea mays saccharata], broad bean [Vicia faba], Japanese radish [Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus], white radish [R. sativus var. longipinnatus] sprout, Jew's marrow [Corchorus olitorius] and cauliflower [Brassica oleracea var. botrytis]). The results of the esRAGE production of these eight samples on HUVECs are summarized in Figure 1. Figure 1a shows the effects of the eight samples (10 μL) on esRAGE production in high glucose-induced HUVECs. The esRAGE production resulting from high glucose treatment was induced when cells were treated with 8 plant extracts as compared to control treated with 4.5 g/L of glucose only. Genistein (10 μM) increased esRAGE production by approximately 12%, but EGCG (10 μM) caused no increase. The results for plant samples suggest that white radish sprout, Jew's marrow and cauliflower have esRAGE production potential on induced endothelial cells. In particular, white radish sprout, which had higher esRAGE production potential than genistein, significantly (P < 0.01) increased esRAGE production. In addition, white radish sprout showed an esRAGE production potential approximately 2.4 times higher than the control (4.5 g/L of glucose only). On the other hand, in 100 μL MEEP [Figure 1b], more samples had a significant influence on esRAGE production. The results suggest that eggplant, carrot peel, young sweet corn, broad bean, Japanese radish, and white radish sprout have esRAGE production potential on induced endothelial cells. However, different MEEP seem to have different effects on esRAGE production in the presence of high glucose. In 100 μM concentration, genistein also showed a tendency to increase slightly, but the increase was not seen in EGCG. In studies to date, no plant has yet been shown to increase esRAGE production. Therefore, the mechanism by which white radish sprout and the seven other kinds of plants increased esRAGE production is unclear. However, it was reported through similar experimental techniques that Hibiscus sabdariffa polyphenolic extract inhibited the expression of RAGE.[21] Furthermore, Lu et al.[22] indicated that atorvastatin exerted a beneficial effect on diabetic nephropathy with reduced AGE accumulation, down-regulating RAGE expression and up-regulating sRAGE in the kidney. From the above-mentioned report, the increase in esRAGE production may be considered to result from the down-regulation of RAGE by the polyphenolic extract. However, although Lee and Lee[14] show that 5 μM EGCG down-regulates the RAGE expression, this may not necessarily indicate an inverse correlation between RAGE and esRAGE because in our study 10 μM EGCG does not increase esRAGE production. This supposition requires further study.

Figure 1.

Effect of methanolic extracts from eight plants on endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products (esRAGE) production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells cultured in high glucose. The esRAGE productions of control (dimethyl sulfoxide) and samples in human umbilical vein endothelial cells cultured in high (4.5 g/L) glucose are indicated by unshaded and shaded columns, respectively. Two groups of experiments were formed, one receiving continuous 10 μL methanolic extracts from edible plants (MEEP) (a) and the other receiving continuous 100 μL MEEP (b) Values are the mean ± standard deviation of three measurements. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the controls

Receptor for advanced glycation end products plays the essential role in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications. Skrha et al.[23] performed the study to compare concentration of sRAGE and its ligands (EN-RAGE and HMGB1) in type 1 (T1DM) and T2DM. Serum sRAGE concentration was higher in T1DM as compared to controls. Similarly, EN-RAGE was significantly higher in both diabetic groups and HMGB1 concentrations were elevated in T2DM patients. They concluded that serum sRAGE and RAGE ligands concentrations reflect endothelial dysfunction developing in diabetes. Therefore, the extract of these eight plants may have an effect on T2DM disease restraint through esRAGE production.

On the other hand, some reports show esRAGE and RAGE to be related to guanosine in DNA[16,17] and peroxynitrite radicals.[18] On other word, Ohe et al.[16] showed that mutagenesis of the G-rich cis-elements caused an increase in the esRAGE/membrane-bound RAGE ratio in the minigene-transfected cells. In addition, Liu et al.[18] showed that administration of EUK134 (peroxynitrite scavenger) attenuated RAGE expression, and decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic mice. Therefore, we examined the correlation between esRAGE production, and the two indicators mentioned above (peroxynitrite and 8-OHdG levels) to determine the mechanism for increasing esRAGE production in HUVECs treated with a eight plant extracts.

Assessment of the relationship between 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine level and endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production

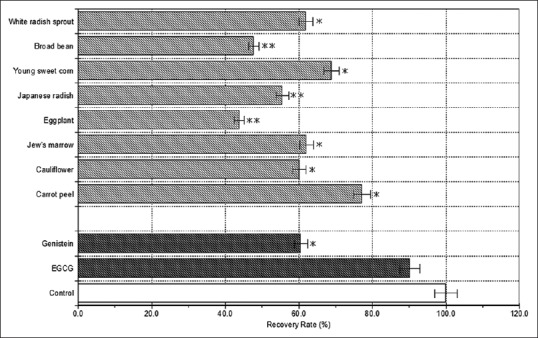

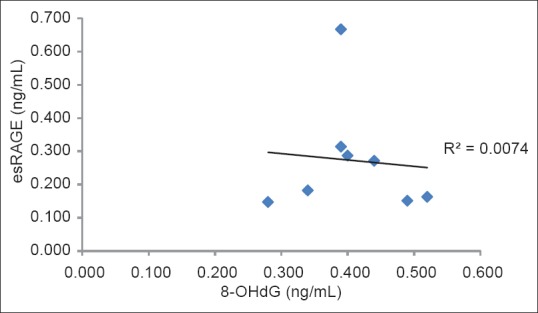

Deoxyribose was used as a detector molecule to identify radical damage. Oyama et al.[24] showed that the amount of 8-OHdG in the medium increased to a significantly greater extent in high glucose-incubated HUVECs than in low glucose-incubated HUVECs. In our experiment, significant differences were observed for 8-OHdG levels among the eight plant varieties. The level of 8-OHdG was in the range of 0.28-0.52 ng/mL (data not shown). Mizutani et al.[25] showed that genistein reduced AGEs-induced 8-OHdG formation. The formation of 8-OHdG in calf thymus DNA by 3-morpholinosydnomine N-ethylcarbamide (SIN-1; peroxynitrite donor) was also inhibited by EGCG.[26] In our experiment, EGCG (100 μM) showed 8-OHdG recovery rates of approximately 90%, but genistein (100 μM) caused 8-OHdG recovery rates of approximately 60%. The calculated 8-OHdG recovery rates for white radish sprout, broad bean, young sweet corn, Japanese radish, eggplant, Jew's marrow, cauliflower, and carrot peel were 61.9%, 47.7%, 68.9%, 55.5%, 43.8%, 62.0%, 60.2%, and 77.1%, respectively in comparison to the normal glucose medium [Figure 2] indicating that the samples are potent inhibitors of 8-OHdG. In particular, carrot peel and young sweet corn which had higher 8-OHdG recovery rate potential than genistein, significantly (P < 0.05) decreased 8-OHdG level. In addition, carrot peel showed an 8-OHdG recovery rate in the vicinity of EGCG. Figure 3 shows the correlation between esRAGE production and 8-OHdG level of eight plant extracts. The results show that the 8-OHdG level does not correlate with esRAGE production (r = −0.086).

Figure 2.

The calculated 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) recovery rates of methanolic extracts from eight plants. The 8-OHdG recovery rates of control (normal glucose medium) and samples (high glucose medium) are indicated by unshaded and shaded columns, respectively. Values are the mean ± standard deviation of three measurements. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the controls.

Figure 3.

The correlation between endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine level of methanolic extracts from eight plants

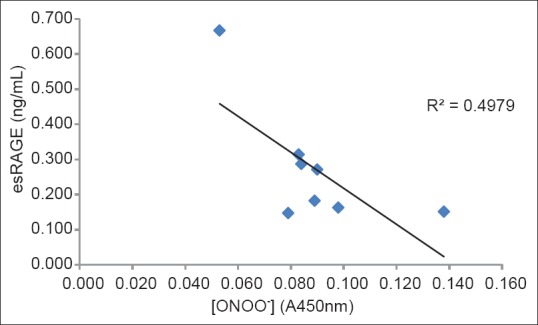

Assessment of the relationship between peroxynitrite level and endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production

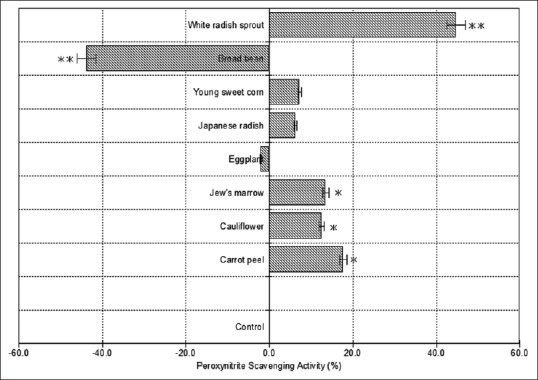

Figure 4 shows the calculated peroxynitrite scavenging activities of eight extracts. Because peroxynitrite has a short half-life, the measurement of the intracellular scavenging activity is difficult. Therefore, we performed the scavenging activity measurement of the sample in the test tube. Amongst the eight extracts, white radish sprout revealed the highest scavenging activity (44.8%). However, eggplant and broad bean did not show this activity. Figure 5 shows the correlation between esRAGE production and peroxynitrite level of the eight plant extracts. The peroxynitrite level significantly correlated with esRAGE production (r = -0.706, P < 0.10). The results showed a negative correlation between esRAGE production and peroxynitrite level. Wu et al.[27] showed that treatment of sinoaortic denervated rats with sRAGE abated aortic oxidative stress. This was marked by reduction in the formation of peroxynitrite indicating that there may be an association between peroxynitrite and esRAGE.

Figure 4.

The calculated peroxynitrite scavenging activities of eight extracts in the test tube. Values are the mean ± standard deviation of three measurements. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the controls

Figure 5.

The correlation between endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production and peroxynitrite level of methanolic extracts from eight plants

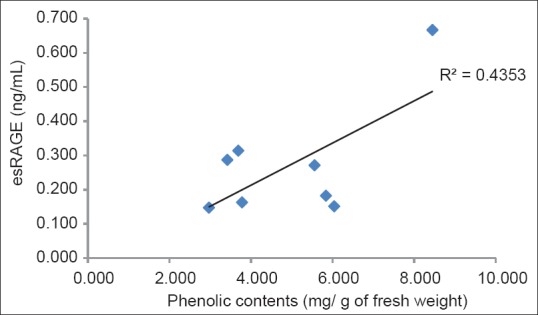

Assessment of the relationship between total phenolic content and endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production

The correlation between esRAGE production and TPC was analyzed [Figure 6]. The TPC of the eight MEEP significantly correlated with esRAGE production. The correlation coefficient for esRAGE production was found to be greater than 0.6 (r = 0.660, P < 0.10). A positive correlation between esRAGE production and TPC was found in the eight MEEP. This result proved that the TPC of these plants could be clearly attributed to their esRAGE production.

Figure 6.

The correlation between endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products production and total phenolic content of methanolic extracts from eight plants

The molecular mechanisms underlying these effects are unknown. However, the seven MEEP[28,29,30,31,32,33,34] except for eggplant contain a lot of quercetin. Because there was a positive correlation between TPC and esRAGE [Figure 6], it is very likely to be quercetin that had an effect. The effect of these seven plants may resemble the mechanism that Zhang et al.[35] showed. Hyperoside, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, is a flavonoid isolated from many medicinal plants. In their studies, quiescent ECV304 (human endothelial-like) cells were treated in vitro with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the presence or absence of hyperoside. The results demonstrated that AGEs induced c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) activation and apoptosis in ECV304 cells. Hyperoside inhibited these effects and promoted ECV304 cell proliferation. Furthermore, hyperoside significantly inhibited RAGE expression in AGE-stimulated ECV304 cells, whereas knockdown of RAGE inhibited AGE-induced JNK activation. These results suggested that AGEs may promote JNK activation, leading to viability inhibition of ECV304 cells via the RAGE signaling pathway. These effects could be inhibited by hyperoside. Furthermore, from the above-mentioned report,[22] the increase in esRAGE production may be considered a result of the down-regulation of RAGE by the polyphenolic extract. Our findings suggest a novel role for eight edible plants in the treatment and prevention of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant No. 18650218) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chawla D, Bansal S, Banerjee BD, Madhu SV, Kalra OP, Tripathi AK. Role of advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced receptor (RAGE) expression in diabetic vascular complications. Microvasc Res. 2014;95C:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Xu H, Hu Y, He P, Ni Z, Xu H, et al. Edaravone protected human brain microvascular endothelial cells from methylglyoxal-induced injury by inhibiting AGEs/RAGE/oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirban A, Gawlowski T, Roden M. Vascular effects of advanced glycation endproducts: Clinical effects and molecular mechanisms. Mol Metab. 2014;3:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yonekura H, Yamamoto Y, Sakurai S, Watanabe T, Yamamoto H. Roles of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts in diabetes-induced vascular injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97:305–11. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cpj04005x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee D, Lee KH, Park H, Kim SH, Jin T, Cho S, et al. The effect of soluble RAGE on inhibition of angiotensin II-mediated atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. The diverse ligand repertoire of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts and pathways to the complications of diabetes. Vascul Pharmacol. 2012;57:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piarulli F, Lapolla A, Ragazzi E, Susana A, Sechi A, Nollino L, et al. Role of endogenous secretory RAGE (esRAGE) in defending against plaque formation induced by oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan KC, Chow WS, Tso AW, Xu A, Tse HF, Hoo RL, et al. Thiazolidinedione increases serum soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1819–25. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0759-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tam HL, Shiu SW, Wong Y, Chow WS, Betteridge DJ, Tan KC. Effects of atorvastatin on serum soluble receptors for advanced glycation end-products in type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam JK, Wang Y, Shiu SW, Wong Y, Betteridge DJ, Tan KC. Effect of insulin on the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) Diabet Med. 2013;30:702–9. doi: 10.1111/dme.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schini-Kerth VB, Auger C, Kim JH, Etienne-Selloum N, Chataigneau T. Nutritional improvement of the endothelial control of vascular tone by polyphenols: Role of NO and EDHF. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:853–62. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khattak KF. Nutrient composition, phenolic content and free radical scavenging activity of some uncommon vegetables of Pakistan. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:277–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang JT, Park IJ, Shin JI, Lee YK, Lee SK, Baik HW, et al. Genistein, EGCG, and capsaicin inhibit adipocyte differentiation process via activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SJ, Lee KW. Protective effect of (-)-epigallocatechin gallate against advanced glycation endproducts-induced injury in neuronal cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1369–73. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung DH, Kim YS, Kim JS. Screening system of blocking agents of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts in cells using fluorescence. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:1826–30. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohe K, Watanabe T, Harada S, Munesue S, Yamamoto Y, Yonekura H, et al. Regulation of alternative splicing of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) through G-rich cis-elements and heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H. J Biochem. 2010;147:651–9. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Q, Liao J, Kobayashi M, Yamashita M, Gu L, Gohda T, et al. Candesartan reduced advanced glycation end-products accumulation and diminished nitro-oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic KK/Ta mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:3012–20. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Qu Y, Wang R, Ma Y, Xia C, Gao C, et al. The alternative crosstalk between RAGE and nitrative thioredoxin inactivation during diabetic myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E841–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00075.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crow JP. Dichlorodihydrofluorescein and dihydrorhodamine 123 are sensitive indicators of peroxynitrite in vitro: Implications for intracellular measurement of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:145–57. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Ohlander M, Jeppsson N, Björk L, Trajkovski V. Changes in antioxidant effects and their relationship to phytonutrients in fruits of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) during maturation. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:1485–90. doi: 10.1021/jf991072g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng CH, Chyau CC, Chan KC, Chan TH, Wang CJ, Huang CN. Hibiscus sabdariffa polyphenolic extract inhibits hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and glycation-oxidative stress while improving insulin resistance. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:9901–9. doi: 10.1021/jf2022379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu L, Peng WH, Wang W, Wang LJ, Chen QJ, Shen WF. Effects of atorvastatin on progression of diabetic nephropathy and local RAGE and soluble RAGE expressions in rats. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:652–9. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1101004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skrha J, Jr, Kalousová M, Svarcová J, Muravská A, Kvasnicka J, Landová L, et al. Relationship of soluble RAGE and RAGE ligands HMGB1 and EN-RAGE to endothelial dysfunction in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:277–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyama T, Miyasita Y, Watanabe H, Shirai K. The role of polyol pathway in high glucose-induced endothelial cell damages. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73:227–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizutani K, Ikeda K, Nishikata T, Yamori Y. Phytoestrogens attenuate oxidative DNA damage in vascular smooth muscle cells from stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2000;18:1833–40. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon HK, Yang ES, Park JW. Protection of peroxynitrite-induced DNA damage by dietary antioxidants. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;29:213–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02969396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu F, Feng JZ, Qiu YH, Yu FB, Zhang JZ, Zhou W, et al. Activation of receptor for advanced glycation end products contributes to aortic remodeling and endothelial dysfunction in sinoaortic denervated rats. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto T, Ueda Y, Oi N, Sakakibara H, Piao C, Ashida H, et al. Effects of combined administration of quercetin, rutin, and extract of white radish sprout rich in kaempferol glycosides on the metabolism in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:279–81. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed FA, Ali RF. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of fresh and processed white cauliflower. Biomed Res Int 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/367819. 367819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma K, Nakayama M, Koshioka M, Ippoushi K, Yamaguchi Y, Kohata K, et al. Phenolic antioxidants from the leaves of Corchorus olitorius L. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3963–6. doi: 10.1021/jf990347p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulin MJ, Bel-Rhlid R, Piché Y, Chênevert R. Flavonoids released by carrot (Daucus carota) seedlings stimulate hyphal development of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the presence of optimal CO2 enrichment. J Chem Ecol. 1993;19:2317–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00979666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozema J, Björn LO, Bornman JF, Gaberscik A, Häder DP, Trost T, et al. The role of UV-B radiation in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems - An experimental and functional analysis of the evolution of UV-absorbing compounds. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2002;66:2–12. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biesaga M. Influence of extraction methods on stability of flavonoids. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:2505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beevi SS, Narasu ML, Gowda BB. Polyphenolics profile, antioxidant and radical scavenging activity of leaves and stem of Raphanus sativus L. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2010;65:8–17. doi: 10.1007/s11130-009-0148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Sethiel MS, Shen W, Liao S, Zou Y. Hyperoside downregulates the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and promotes proliferation in ECV304 cells via the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway following stimulation by advanced glycation end-products in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:22697–707. doi: 10.3390/ijms141122697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]