Abstract

Malaria infection treatment vaccine (ITV) is a promising strategy to induce homologous and heterologous protective immunity against the blood stage of the parasite. However, the underlying mechanism of protection remains largely unknown. Here, we found that a malaria-specific antibody (Ab) could mediate the protective immunity of ITV-immunized mice. Interestingly, PD-1 deficiency greatly elevated the levels of both malaria-specific total IgG and subclass IgG2a and enhanced the protective efficacy of ITV-immunized mice against the blood-stage challenge. A serum adoptive-transfer assay demonstrated that the increased Ab level contributed to the enhanced protective efficacy of the immunized PD-1-deficient mice. Further study showed that PD-1 deficiency could also promote the expansion of germinal center (GC) B cells and malaria parasite-specific TFH cells in the spleens of ITV-immunized mice. These results suggest that PD-1 deficiency improves the protective efficacy of ITV-immunized mice by promoting the generation of malaria parasite-specific Ab and the expansion of GC B cells. The results of this study provide new evidence to support the negative function of PD-1 on humoral immunity and will guide the design of a more effective malaria vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

Although malaria control programs have led to an extensive reduction in malaria incidence and mortality, malaria remains one of the most threatening diseases worldwide. It is estimated that 207 million cases and 627,000 malaria deaths occurred in 2012 (1).

A vaccine is regarded as the most cost-effective strategy to prevent malaria infection (2). Most malaria subunit blood-stage vaccines have been designed to induce antibodies (Ab) against a variety of surface proteins on the merozoite to block the invasion of red blood cells (RBCs) (3). However, the invasion of the merozoites into red blood cells is controlled by multiple redundant proteins (4), and Ab against one or two merozoite surface proteins are unable to effectively prevent the infection of red blood cells with the malaria parasite (4). Furthermore, most merozoite surface proteins exhibit antigenic polymorphism under selective pressure (5). To date, there is no malaria subunit vaccine available worldwide.

In contrast to the subunit malaria vaccine, the malaria infection treatment vaccine (ITV), which involves infection with live malaria parasites under curative antimalarial drug coverage, has been reported to induce antibodies specific for the merozoite surface antigens conserved between heterologous strains but not for the variant surface antigens (6). ITV induces strong protective immunity against the blood stage of the parasite in animals (7) and humans (8). Interestingly, ITV can also confer cross-protection against the liver stage of malaria by inducing cellular immune responses (7). However, the underlying mechanism of protective immunity induced by ITV is still largely unknown.

Follicular helper CD4 T(TFH) cells are characterized by the high expression of chemokine receptor CXCR5, programmed death 1 (PD-1), lineage-specific transcription regulator Bcl6, SAP (SH2D1A), interleukin-21, and ICOS and are recognized as specialized providers of cognate B cell help (9). Of these characteristic molecules, PD-1 has been reported to provide modulatory signals to germinal center (GC) TFH cells, but its function in the modulation of humoral immunity remains unresolved. Some evidence has shown that the blockade of PD-L1 or PD-1 reinforces TFH cell expansion, increases the number of GC B cells and plasmablasts, and enhances antigen-specific Ab responses (10, 11). However, attenuated humoral immune responses also have been observed after blockade of PD-1 signaling (12–14). Therefore, the exact role of PD-1 signaling in the protective immunity of the ITV-immunized mice remains unclear.

In this study, we found that PD-1 deficiency greatly improved the protective efficacy of ITV-immunized mice against a malaria blood-stage challenge. This phenomenon was attributed to the elevated malaria parasite-specific Ab in the immunized PD-1-deficient mice. In addition, we also observed increased GC B cells and the expansion of TFH cells in immunized PD-1-deficient mice. Thus, our data further confirmed the negative effect of PD-1 signaling on humoral immunity and shed new light on the design of effective malaria vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and Plasmodium parasites.

PD-1−/− mice (BALB/c background) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice, at 6 to 8 weeks of age, were purchased from the Beijing Animal Institute. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University Institute of Medical Research. The lethal strain Plasmodium yoelii 17XL was obtained from MR4 (Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center, Manassas, VA) and maintained by intraperitoneal (i.p.) passages in mice.

Immunization and challenge.

The immunization schedule was performed as previously described (7) with minor modifications. Briefly, mice were intravenously (i.v.) injected with 106 P. yoelii 17XL infected RBCs (Py-iRBCs) or an equivalent amount of normal RBCs with or without 100 μl of 8 mg of chloroquine (CQ; Sigma-Aldrich)/ml diluted in saline daily for 15 days starting from the day of iRBC injection. The mice were maintained for 21 days after the last CQ injection to allow complete elimination of the drug and challenged i.p. with 106 Py-iRBCs.

Adoptive serum transfer assay and CD4+ T cell depletion.

For serum transfer, naive BALB/c mice were injected i.v. on days −1, 0, and 1 with 0.2 ml of naive mouse serum, ITV-immunized wild-type (WT) serum, or PD-1−/− mouse serum collected 21 days after the last CQ injection, as described previously (15). The mice were challenged with 2.5 × 104 Py-iRBCs on day 0, and parasitemia and the survival rate were determined. For CD4 depletion studies, an anti-CD4-depleting monoclonal antibody (GK1.5 clone, 200 μg per mouse in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]; BioXcell) or control Ab was injected i.p. on days −1 and 1 (i.e., 20 and 22 days after the last CQ injection) according to a previously described protocol (16). CD4+ T cell depletion was verified by staining blood samples with anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5; eBioscience). The mice were then challenged with 106 Py-iRBCs on day 0.

Detection of malaria-specific IgG in serum.

Sera were collected from naive mice, ITV-immunized WT mice, and PD-1−/− mice at 21 days after the last CQ injection. Hyperimmune sera were collected from the ITV-immunized WT mice that had recovered from the P. yoelii 17XL infection. The malaria-specific total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a in the serum were detected as previously described (15, 17). Briefly, P. yoelii 17XL-infected mouse blood was collected, lysed with 0.01% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 20 min, and sonicated in PBS. Nunc MaxiSorp immunoplates (Nalge Nunc) were coated with parasite antigen at a concentration of 5 to 10 μg/ml overnight at 4°C and coincubated with serial dilutions of sera from the ITV-immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice. Biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 and IgG2a (BioLegend) were added to the plates to detect IgG1 and IgG2a. After a washing step with wash buffer, the plates were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or HRP-conjugated streptavidin (BioLegend), and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine was added (BioLegend). The absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was read using a spectrophotometer.

Flow cytometry analysis of GC B and malaria-specific TFH cells.

Both GC B and malaria-specific TFH cells from the naive mice and ITV-immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice were analyzed at 7, 9, 11, 14, and 21 days (at 21, 23, 25, 28, and 35 days after the start of CQ treatment, respectively) after the last CQ injection. In brief, single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were prepared and washed in flow cytometry buffer (PBS with 2% fetal calf serum and 0.05% sodium azide), followed by blocking with anti-mouse CD16/32 (BioLegend). For the GC B cell analysis, 106 cells were incubated with anti-mouse B220 allophycocyanin (APC; BioLegend), anti-mouse CD95 phycoerythrin (PE; eBioscience), and anti-mouse T and B cell activation marker (GL-7) fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; BioLegend). For the malaria-specific TFH cell analysis, 2 × 106 cells were incubated with anti-mouse CXCR5 biotin (BioLegend), streptavidin-APC (BioLegend), anti-mouse CD4 APC/Cy7 (BioLegend), anti-mouse CD11a percp/Cy5.5 (BioLegend), anti-mouse CD49d FITC (BioLegend), anti-mouse ICOS PE/Cy7 (BioLegend), or anti-mouse Bcl6 PE (eBioscience) after the cells were permeabilized with fixation/permeabilization agent (eBioscience). The cells were then analyzed by using flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between samples were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Since our data were not confirmed to be normally distributed, nonparametric tests were used to determine the statistical significance between groups. We use the Mann-Whitney test to compare two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare more than two groups. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

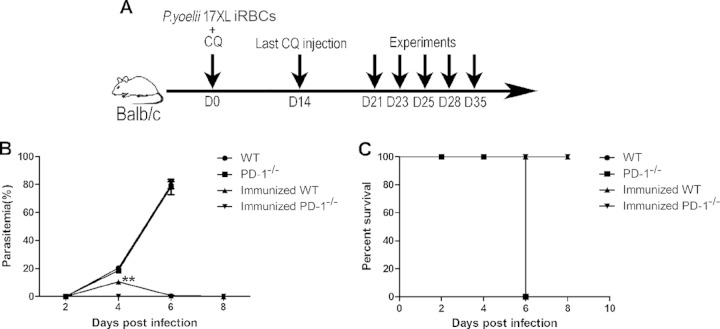

The absence of PD-1 greatly enhanced the protective efficacy in the ITV-immunized mice.

To determine whether PD-1-deficiency could enhance the protective efficacy in the ITV-immunized mice, the parasitemia levels and survival rates of the ITV-immunized WT and PD-1-deficient mice were compared after a blood-stage challenge, as depicted in Fig. 1. The parasitemia curves of the PD-1-deficient mice were comparable to those of WT mice, indicating that the PD-1-deficient mice had no intrinsic resistance to the malaria parasite. However, compared to the nonimmunized mice, the growth of parasite in either ITV-immunized WT mice or PD-1-deficient mice was greatly suppressed. The peak parasitemia in the immunized WT mice was 10.47% ± 0.095% but only 0.017% ± 0.029% in immunized PD-1−/− mice at day 4 after live P. yoelii 17XL challenge (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.01). Parasites were cleared from all immunized mice at day 8 postchallenge, and all of the mice survived (Fig. 1C). These data demonstrate that a PD-1 deficiency could largely augment the protective efficacy of the ITV protocol.

FIG 1.

The protective efficacy against blood-stage challenge was markedly enhanced in the ITV-immunized PD-1−/− mice. (A) Procedure for the ITV immunization and challenge. (B and C) Naive or immunized WT (n = 5) and PD-1−/− (n = 5) mice were challenged i.p. with P. yoelii 17XL iRBCs at day 21 after the last CQ injection. The parasitemia and survival rate were recorded. The results are representative of three independent experiments. The data are presented as means ± the standard deviations (SD). **, P < 0.01.

Malaria parasite-specific Ab was necessary for the protective immunity of the ITV-immunized mice.

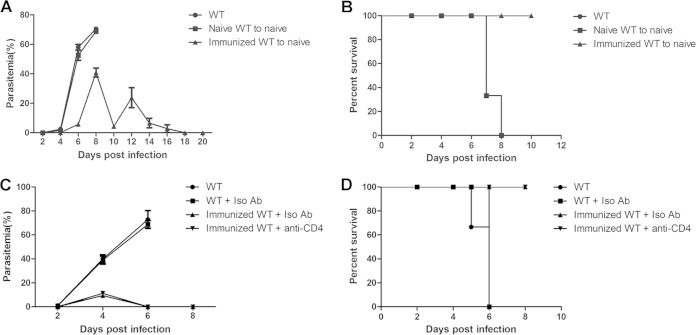

To elucidate the mechanism of the augmented protective efficacy in the immunized PD-1−/− mice, we first determined the protective immunity of the ITV-immunized mice. Both Ab and CD4+ T cell responses are essential for controlling the malaria blood-stage development (18). Therefore, sera from either naive mice or ITV-immunized mice were adoptively transferred to naive mice, and the recipient mice were then challenged with live P. yoelii 17XL. The resulting parasitemia levels of the mice that received naive mouse sera were comparable to those of naive mice, and all of the mice died. However, the mice that received sera from the ITV-immunized mice serum cleared the parasites at day 18 postchallenge, and all of the mice survived (Fig. 2A and B). These data strongly suggest that antibodies can mediate the protection of ITV-immunized mice against malaria parasite challenge.

FIG 2.

Protective immunity of the ITV-immunized WT mice. (A and B) Sera from the naive mice or ITV-immunized WT mice were adoptively transferred into each naive mouse (n = 3) at days −1, 0, and 1. All mice were challenged with P. yoelii 17XL on day 0, and the parasitemia (A) and survival rate (B) were determined. (C and D) On days −1 and 1 before the challenge, immunized WT mice (n = 3) were injected with anti-CD4 or control IgG. All of the mice were then challenged with P. yoelii 17XL on day 0, and the parasitemia and survival rate were monitored. All experiments were performed twice. The data are presented as means ± the SD.

Next, the CD4+ T cells of the immunized WT mice were depleted, and the mice were challenged with P. yoelii 17XL. As shown in Fig. 2C and D, no significant difference in the parasitemia or survival rate was found between the ITV-immunized mice injected with control Ab and those injected with anti-CD4 Ab. Thus, in contrast to Ab, the data suggest that CD4+T cells are not essential for ITV-immunized mice against the blood-stage challenge.

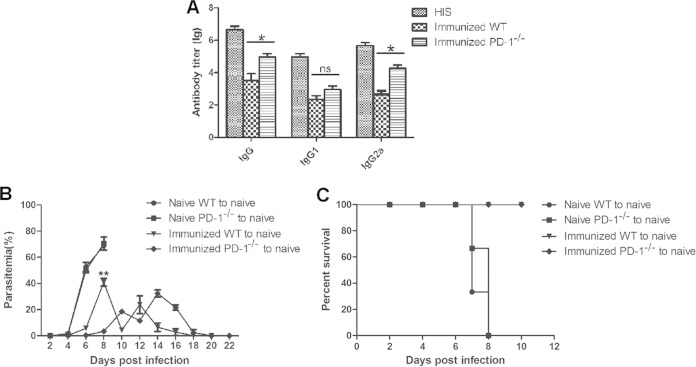

Elevated malaria-specific Ab greatly contribute to enhanced protective efficacy in the immunized PD-1−/− mice.

Because Ab are capable of mediating the protective immune response of the ITV-immunized mice, the levels of malaria-specific IgG were compared between the ITV-immunized WT mice and PD-1−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 3A, the levels of malaria parasite-specific total IgG and isotype IgG2a in immunized WT mice were much lower than those in the immunized PD-1−/− mice (IgG, P < 0.05; IgG2a, P < 0.05), although no significant difference in the IgG1 levels was found between the two types of immunized mice (IgG1, P > 0.05). Thus, these data suggest that the augmented protective efficacy in immunized PD-1−/− mice was closely associated with the elevated levels of malaria-specific Ab.

FIG 3.

Elevated malaria-specific Ab contributed to the enhanced protective efficacy of the ITV-immunized PD-1−/− mice. (A) Three weeks after the final immunization, the levels of total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a in the sera of both immunized WT (n = 5) and PD-1−/− (n = 5) mice were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Sera from PBS-immunized mice served as the negative control, and hyperimmune sera served as the positive control. The data are presented as the log (lg) of the Ab titer. (B and C) Sera from the naive mice, ITV-immunized WT mice, or PD-1−/− mice were adoptively transferred into each naive mouse (n = 3) at days −1, 0, and 1, and all mice were then challenged with P. yoelii 17XL. The parasitemia and survival rate were determined. ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To confirm that the elevated Ab contributed to the improved protective immunity of the ITV-immunized PD-1−/− mice, sera from the ITV-immunized WT mice or PD-1−/− mice were adoptively transferred to naive mice, and the recipient mice were then challenged with P. yoelii 17XL. As a result, the appearance of parasite in the blood of the mice that received the immunized PD-1-deficient mouse sera was delayed by 2 days compared to that of mice who received the immunized WT mouse sera (Fig. 3B). Although all mice receiving sera from either type of immunized mouse survived (Fig. 3C), the parasitemia in mice that received immunized PD-1-deficient mouse sera was only 3.38% ± 0.69%, i.e., much lower than that of the mice that received sera from the immunized WT mice (40.86% ± 5.22%) at day 8 after live P. yoelii 17XL challenge (P < 0.01). Therefore, these data strongly suggest that the elevated malaria-specific Ab greatly contribute to the enhanced protective efficacy in the ITV-immunized PD-1−/− mice.

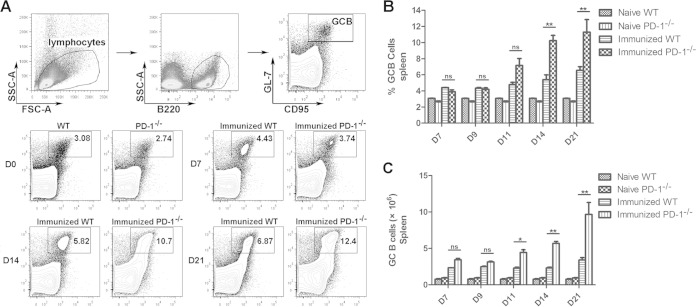

The frequency and number of GC B cells significantly increased in immunized PD-1-deficient mice.

To further confirm the role of PD-1 signaling in the regulation of Ab production, the frequencies of GC B cells in the spleen were detected at days 7, 9, 11, 14, and 21 after the final injection of CQ. As shown in Fig. 4, the frequency and number of GC B cells in both ITV-immunized WT mice and PD-1−/− mice gradually increased over time. However, the GC B frequency and number of the ITV-immunized PD-1−/− mice were much higher than those of the ITV-immunized mice at days 14 and 21 (P < 0.01), but no significant difference was found either at day 7 or day 9 after the final injection of CQ. These results suggest that PD-1 deficiency could promote the expansion of GC B cells in the spleens of immunized WT mice; this conclusion is in agreement with the elevated level of Ab in the sera.

FIG 4.

Frequency and number of GC B cells in the spleens of the ITV-immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice. Splenocytes were isolated from immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice at the indicated times after the final immunization, and both the frequency and the number of GC B cells were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). (A) Representative FACS analysis of B220+ GL-7+ CD95+ GC B cells at days 7, 14, and 21. (B and C) Statistical analysis of the frequency and number of GC B cells from the ITV-immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice at days 7, 9, 11, 14, and 21. Three individual experiments were performed. The data are presented as means ± the SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

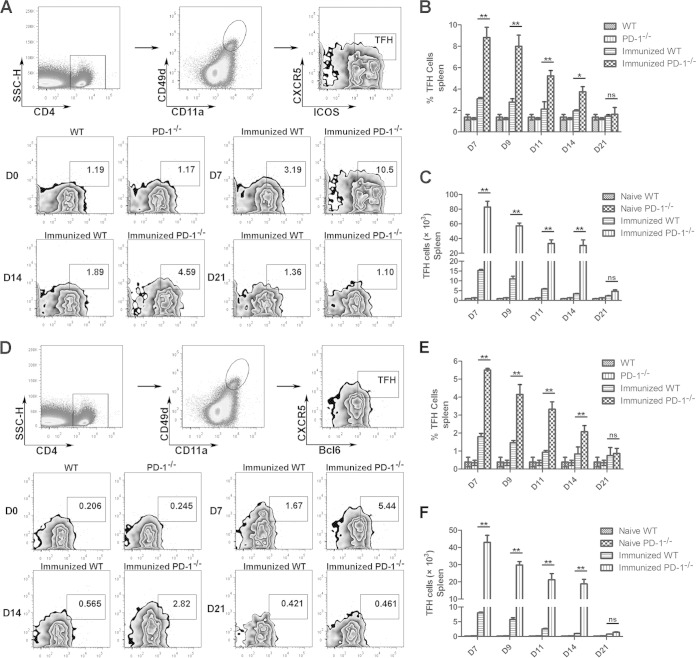

Plasmodium-specific TFH cells expanded in the immunized PD-1−/− mice.

TFH cells can provide help to GC B cells for the generation of GCs and long-term protective humoral responses (19, 20). To test whether the increased GC B cells frequency in the ITV-immunized PD-1-deficient mice was a result of the expansion of TFH cells, the frequency and number of splenic TFH cells were compared between immunized WT mice and PD-1−/− mice. As described in the previous study (9), we used the activation markers CD4, CXCR5, and ICOS and the transcription factor Bcl6 to characterize splenic TFH cells. In addition, the coordinated upregulation of the integrins CD49d and CD11a on antigen-experienced CD4+ T cells has also been used to identify Plasmodium-specific CD4+ T cells (21). Therefore, CD4+ CD11a+ CD49d+ CXCR5+ ICOS+ or CD4+ CD11a+ CD49d+ CXCR5+ Bcl6+ cells were considered Plasmodium-specific TFH cells in our study (Fig. 5A and D).

FIG 5.

Frequency and number of malaria-specific TFH cells from ITV-immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice. Splenocytes were isolated from the immunized WT (n = 5) and PD-1−/− mice (n = 5) at the indicated day after the final immunization, and the TFH cells were analyzed by FACS. (A) Representative FACS analysis of CD4+ CD11a+ CD49+ CXCR5+ ICOS+ malaria-specific TFH cells. (B and C) Statistical analysis of the frequency and number of CD4+ CD11a+ CD49+ CXCR5+ ICOS+ cells in the immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice. (D) Representative FACS analysis of CD4+ CD11a+ CD49+ CXCR5+ Bcl6+ malaria-specific TFH cells at days 7, 14, and 21. (E and F) Statistical analysis of the frequency and number of TFH cells (CD4+ CD11a+ CD49+ CXCR5+ Bcl6+) from immunized WT and PD-1−/− mice at days 7, 9, 11, 14, and 21. Three experiments were performed. The data are presented as means ± the SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

The frequency and number of TFH cells in both ITV-immunized WT mice and PD-1−/− mice gradually decreased over time (Fig. 5B, C, E, and F). The highest TFH cell frequencies and numbers were observed at day 7 after the final injection of CQ, which is consistent with previous reports (22, 23), and the frequency and number were reduced to the baseline level at day 21. However, the frequencies and numbers of CD4+ CD11a+ CD49d+ CXCR5+ ICOS+ TFH cells or CD4+ CD11a+ CD49d+ CXCR5+ Bcl6+ TFH cells from the immunized PD-1−/− mice were >3-fold greater than those of immunized WT mice at day 7 after the final injection of CQ (P < 0.01; Fig. 5). Thus, the increased malaria parasite-specific TFH cells were closely associated with the expansion of GC B cells and elevated Ab in the sera.

DISCUSSION

Due to the failure of malaria blood-stage subunit vaccines, whole-parasite vaccines, such as ITV (7), whole-killed parasites (17), and genetically attenuated parasites (24, 25), have received more attention from researchers in recent years. Understanding the underlying mechanism of the whole-parasite vaccine would help in the design of a more effective malaria vaccine. Here, we found that the production of malaria parasite-specific antibodies were capable of mediating protection of the ITV-immunized mice. Interestingly, PD-1 deficiency leads to the sterile protection of the ITV-immunized mice against the malaria blood stage; this phenomenon was correlated to the elevated malaria parasite-specific Ab in the serum. In addition, the elevated malaria parasite-specific Ab was closely associated with the expansion of GC B cells and malaria parasite-specific TFH cells in immunized PD-1-deficient mice.

We found that the adoptive transfer of ITV-immunized mouse sera could delay and reduce the parasitemia after a blood-stage challenge (Fig. 2), although its effect was short-term likely due to the clearance of antibodies following binding to the parasites. Except for the high level of malaria-specific Ab, the possible changed antibody affinity, which was not tested in our study, might also contribute to the enhanced protective immunity of ITV-immunized mice. However, CD4+ T cell depletion prior to the challenge (day 21) did not alter the protection of the ITV-immunized mice, although a great expansion of TFH was observed early (days 7, 9, 11, and 14) after the vaccination (Fig. 5). In addition, blockade of PD-L1 and LAG-3 could promote the differentiation of CD4+ TFH cells and plasmablasts in malaria infection (21). These data show that TFH cells might provide the specialized help in the generation of GC B cells and Ab at the early postvaccination stage (9) but not at the late stage when both GC B cells and Ab have already formed. Therefore, the protective immunity of the ITV-immunized mice was largely dependent on the malaria parasite-specific Ab, but a role for CD4+T cells to help antibody response during immunization could not be completely excluded.

Although ITV immunization could induce protective immunity against the blood stage (6) and the liver stage (7) of the parasite, short-term parasitemia was observed after challenge in both our study and other studies (6). Thus, vaccinated individuals may still develop clinical symptoms and may be able to transmit the malaria parasite to mosquitoes after malaria parasite challenge. Interestingly, we found that PD-1 deficiency resulted in the sterile protection of the ITV-immunized mice (Fig. 1); sterile protection would prevent the development of clinical symptom and the transmission of malaria by vaccinated individuals. This type of vaccine would greatly contribute to the elimination of malaria worldwide.

Recently, evidence has shown that parasitized erythroblast could activate CD8+ T cells (26). Although CD8+ T cells were found to be dispensable for the protective effect of ITV-immunized mice against blood-stage challenge (7), it is protective in the immunized mice that survived infection with both P. yoelii XNL and, subsequently, P. yoelii 17XL (27). In addition, previous studies showed that PD-1 signaling could induce CD8+ T cell anergy, not only in virus infection (28, 29) but also in chronic malaria infection (30). Therefore, the contribution of CD8+ T cells to the enhanced protective immunity of the ITV-immunized PD-1-deficient mice still could not be completely excluded.

Although recent studies have revealed that PD-1 signaling can also modulate the T cell-dependent humoral immunity, the reports regarding the function of PD-1 signaling in the control of humoral immunity remain contradictory (10–14). Here, we found PD-1 deficiency could significantly elevate the levels of malaria parasite-specific total IgG and isotype IgG2a in the serum, and it greatly promoted the expansion of both GC B cells and TFH cells in the ITV-immunized mice. Serum adoptive-transfer assays further confirmed the negative role of PD-1 signaling in the control of humoral immunity. This is consistent with a negative regulatory role of PD-1 signaling in the regulation of TFH in chronic malaria infections (21).

PD-1 has two known ligands: PD-L1 and PD-L2. PD-L1 is expressed on a wider range of cells than PD-L2, but both of them can be expressed on GC B cells and dendritic cells (31). Although PD-1/PD-L1 or PD-1/PD-L2 signaling has been reported to modulate TFH cells, GC B cells, and Ab (11, 12), the ligand that is involved in the humoral immunity of ITV-immunized mice remains to be determined. Recently, follicular regulatory T cells (TFR cells) that suppress the GC reaction were identified (32, 33). Because FoxP3 is the only marker that distinguishes TFR from TFH, it seems likely that previously identified “TFH cells” with markers of ICOS, CXCR5, and PD-1 could be mixtures of stimulatory TFH cells and inhibitory TFR cells. Therefore, the effect of PD-1 deficiency on TFH and TFR cells in the ITV-immunized mice warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that malaria parasite-specific Abs are capable of mediating the protective immunity of the ITV-immunized mice. Interestingly, PD-1 deficiency could confer sterile protective immunity to the ITV-immunized mice; this is an important step in the worldwide elimination of malaria. We also provide evidence that PD-1 signaling could greatly enhance the malaria-specific B cell response and the expansion of TFH cells, further supporting the negative role of PD-1 signaling in the modulation of humoral immunity. Thus, our findings not only have implications for the rational design of an effective blood-stage vaccine against malaria parasites through the induction of a robust B cells response but also further our understanding of the regulatory role of PD-1 signaling in the humoral immune response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grant 81271859), the Natural Science Foundation of PLA (CWS12J093), and a major project of PLA (BWS11J041).

We also thank W. Peters and B. L. Robinson from the Malaria Research and the Reference Reagent Resource Center for providing P. yoelii 17XL.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2013. World malaria report 2013. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2013/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delany I, Rappuoli R, De Gregorio E. 2014. Vaccines for the 21st century. EMBO Mol Med 6:708–720. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201403876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genton B, Reed ZH. 2007. Asexual blood-stage malaria vaccine development: facing the challenges. Curr Opin Infect Dis 20:467–475. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282dd7a29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowman AF, Crabb BS. 2006. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mu J, Awadalla P, Duan J, McGee KM, Keebler J, Seydel K, McVean GA, Su XZ. 2007. Genome-wide variation and identification of vaccine targets in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Nat Genet 39:126–130. doi: 10.1038/ng1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott SR, Kuns RD, Good MF. 2005. Heterologous immunity in the absence of variant-specific antibodies after exposure to subpatent infection with blood-stage malaria. Infect Immun 73:2478–2485. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2478-2485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belnoue E, Voza T, Costa FT, Gruner AC, Mauduit M, Rosa DS, Depinay N, Kayibanda M, Vigario AM, Mazier D, Snounou G, Sinnis P, Renia L. 2008. Vaccination with live Plasmodium yoelii blood-stage parasites under chloroquine cover induces cross-stage immunity against malaria liver stage. J Immunol 181:8552–8558. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pombo DJ, Lawrence G, Hirunpetcharat C, Rzepczyk C, Bryden M, Cloonan N, Anderson K, Mahakunkijcharoen Y, Martin LB, Wilson D, Elliott S, Eisen DP, Weinberg JB, Saul A, Good MF. 2002. Immunity to malaria after administration of ultralow doses of red cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Lancet 360:610–617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crotty S. 2011. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol 29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velu V, Titanji K, Zhu B, Husain S, Pladevega A, Lai L, Vanderford TH, Chennareddi L, Silvestri G, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R, Amara RR. 2009. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature 458:206–210. doi: 10.1038/nature07662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hams E, McCarron MJ, Amu S, Yagita H, Azuma M, Chen L, Fallon PG. 2011. Blockade of B7-H1 (programmed death ligand 1) enhances humoral immunity by positively regulating the generation of T follicular helper cells. J Immunol 186:5648–5655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Good-Jacobson KL, Szumilas CG, Chen L, Sharpe AH, Tomayko MM, Shlomchik MJ. 2010. PD-1 regulates germinal center B cell survival and the formation and affinity of long-lived plasma cells. Nat Immunol 11:535–542. doi: 10.1038/ni.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamel KM, Cao Y, Wang Y, Rodeghero R, Kobezda T, Chen L, Finnegan A. 2010. B7-H1 expression on non-B and non-T cells promotes distinct effects on T- and B-cell responses in autoimmune arthritis. Eur J Immunol 40:3117–3127. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamoto S, Tran TH, Maruya M, Suzuki K, Doi Y, Tsutsui Y, Kato LM, Fagarasan S. 2012. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science 336:485–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1217718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Xu G, Guo B, Fu Y, Qiu Y, Ding Y, Zheng H, Fu X, Wu Y, Xu W. 2013. An essential role for C5aR signaling in the optimal induction of a malaria-specific CD4+ T cell response by a whole-killed blood-stage vaccine. J Immunol 191:178–186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abes R, Gelize E, Fridman WH, Teillaud JL. 2010. Long-lasting antitumor protection by anti-CD20 antibody through cellular immune response. Blood 116:926–934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinzon-Charry A, McPhun V, Kienzle V, Hirunpetcharat C, Engwerda C, McCarthy J, Good MF. 2010. Low doses of killed parasite in CpG elicit vigorous CD4+ T cell responses against blood-stage malaria in mice. J Clin Invest 120:2967–2978. doi: 10.1172/JCI39222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Good MF, Xu H, Wykes M, Engwerda CR. 2005. Development and regulation of cell-mediated immune responses to the blood stages of malaria: implications for vaccine research. Annu Rev Immunol 23:69–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gowthaman U, Chodisetti SB, Agrewala JN. 2010. T cell help to B cells in germinal centers: putting the jigsaw together. Int Rev Immunol 29:403–420. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2010.496503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. 2011. Germinal center B and follicular helper T cells: siblings, cousins or just good friends? Nat Immunol 12:472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler NS, Moebius J, Pewe LL, Traore B, Doumbo OK, Tygrett LT, Waldschmidt TJ, Crompton PD, Harty JT. 2011. Therapeutic blockade of PD-L1 and LAG-3 rapidly clears established blood-stage Plasmodium infection. Nat Immunol 13:188–195. doi: 10.1038/ni.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang SG, Liu WH, Lu P, Jin HY, Lim HW, Shepherd J, Fremgen D, Verdin E, Oldstone MB, Qi H, Teijaro JR, Xiao C. 2013. MicroRNAs of the miR-17∼92 family are critical regulators of TFH differentiation. Nat Immunol 14:849–857. doi: 10.1038/ni.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linterman MA, Beaton L, Yu D, Ramiscal RR, Srivastava M, Hogan JJ, Verma NK, Smyth MJ, Rigby RJ, Vinuesa CG. 2010. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med 207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ting LM, Gissot M, Coppi A, Sinnis P, Kim K. 2008. Attenuated Plasmodium yoelii lacking purine nucleoside phosphorylase confer protective immunity. Nat Med 14:954–958. doi: 10.1038/nm.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aly AS, Downie MJ, Mamoun CB, Kappe SH. 2010. Subpatent infection with nucleoside transporter 1-deficient Plasmodium blood-stage parasites confers sterile protection against lethal malaria in mice. Cell Microbiol 12:930–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai T, Ishida H, Suzue K, Hirai M, Taniguchi T, Okada H, Suzuki T, Shimokawa C, Hisaeda H. 2013. CD8+ T cell activation by murine erythroblasts infected with malaria parasites. Sci Rep 3:1572. doi: 10.1038/srep01572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai T, Shen J, Chou B, Duan X, Tu L, Tetsutani K, Moriya C, Ishida H, Hamano S, Shimokawa C, Hisaeda H, Himeno K. 2010. Involvement of CD8+ T cells in protective immunity against murine blood-stage infection with Plasmodium yoelii 17XL strain. Eur J Immunol 40:1053–1061. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier H, Isogawa M, Freeman GJ, Chisari FV. 2007. PD-1–PD-L1 interactions contribute to the functional suppression of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the liver. J Immunol 178:2714–2720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukens JR, Cruise MW, Lassen MG, Hahn YS. 2008. Blockade of PD-1/B7-H1 interaction restores effector CD8+ T cell responses in a hepatitis C virus core murine model. J Immunol 180:4875–4884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horne-Debets JM, Faleiro R, Karunarathne DS, Liu XQ, Lineburg KE, Poh CM, Grotenbreg GM, Hill GR, Macdonald KP, Good MF, Renia L, Ahmed R, Sharpe AH, Wykes MN. 2013. PD-1-dependent exhaustion of CD8+ T cells drives chronic malaria. Cell Rep 5:1204–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. 2008. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, Nurieva RI, Martinez GJ, Rawal S, Wang YH, Lim H, Reynolds JM, Zhou XH, Fan HM, Liu ZM, Neelapu SS, Dong C. 2011. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med 17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, Srivastava M, Divekar DP, Beaton L, Hogan JJ, Fagarasan S, Liston A, Smith KG, Vinuesa CG. 2011. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med 17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]