Abstract

Background

Whether portal hypertension (PHT) is an appropriate contraindication for hepatic resection (HR) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patient is still under debate.

Aims: Our aim was to assess the impact of clinically significant PHT on postoperative complication and prognosis in HCC patients who undergo HR.

Methods

Two hundred and nine HCC patients who underwent HR as the initial treatment were divided into two groups according to the presence (n = 102) or absence (n = 107) of clinically significant PHT. Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was used to compare postoperative outcomes and survival.

Results

Before PSM, PHT patients had higher rates of postoperative complication (43.1% vs. 23.4%; P = 0.002) and liver decompensation (37.3% vs. 17.8%; P = 0.002) with similar rates of recurrence-free survival (RFS; P = 0.369) and overall survival (OS; P = 0.205) compared with that of non-PHT patients. However, repeat analysis following PSM revealed similar rates of postoperative complication (32.2% vs. 39.0%; P = 0.442), liver decompensation (25.4% vs. 32.2%; P = 0.416), RFS (P = 0.481) and OS (P = 0.417; 59 patients in each group). Presence of PHT was not associated with complication by logistic regression analysis, or with overall survival by Cox regression analysis.

Conclusions

The presence of clinically significant PHT had no impact on postoperative complication and prognosis, and should not be regarded as a contraindication for HR in HCC patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatic resection, Portal hypertension, Complication, Prognosis

Background

Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer, the third cause of cancer-related death and accounts for 7% of all cancers [1]. Curable treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) include liver transplantation, hepatic resection (HR) and percutaneous approaches. Portal hypertension (PHT) is considered to be a contraindication for HR in HCC patients according to the 2001 European Association for Study of Liver (EASL). These observations are based on the findings of a study [2] involving 29 patients in 1996 which concluded that PHT, defined as a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) ≥ 10 mmHg, was a predictor of postoperative liver decompensation [2], and another study in 1999 showing that Child-Pugh A patients with PHT have poor survival after HR [3]. Although this conclusion is supported by subsequent studies [4-7], contradictory reports have also been published indicating that HR is safe and beneficial in well-selected HCC patients with PHT because postoperative outcomes and survival are similar, regardless of the presence or absence of clinically significant of PHT [4,8-11].

Consequently, the role of PHT in the prognosis of HCC patients after HR remains a highly debated topic. Nevertheless, the 2012 EASL-EORTC Clinical Practice Guidelines still advise against HR as the first-line treatment option for HCC patients with PHT, defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient ≥ 10 mmHg or with surrogates of portal hypertension, defined as esophageal varices, or splenomegaly with platelet count < 100,000/mm3 [12].

We therefore conducted a retrospective study involving HCC patients who underwent HR as the initial treatment to assess the role of clinically significant PHT in HCC patients after HR. Propensity score matching was used in the analysis to reduce bias in patient selection and to achieve an even distribution of baseline liver function.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively collected data from 1542 patients who underwent HR as the initial treatment for HCC from January 2003 to December 2008 at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in China. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed postoperatively by pathological investigation.

HVPG over 10 mmHg was regarded as the gold diagnosis criteria of PHT. It is not, however, routinely used in clinical practice for its invasiveness. Studies show esophageal varices, low platelet count, low white blood cell count [13], splenomegaly, a portal vein diameter on ultrasound (US) ≥13 mm, a high Child-Pugh score, low prothrombin activity, spider angiomas, and a low platelet to spleen ratio are associated with clinically significant PHT [14]. Therefore, portal hypertension was indirectly defined, which incorporated the BCLC criteria [15] and the Italian Programme on Liver Cirrhosis [16, 17] if two or more of the following criteria were met: 1) Platelet count < 100 × 109/l and/or white blood cell count < 4 × 109/l three times in succession, 2) Splenomegaly (spleen thickness > 4.5 cm via ultrasound or major diameter > 10 cm via CT/MR), 3) Portal vein width > 14 mm or spleen vein width > 10 mm via ultrasound, and 4) Esophageal varices via endoscopy or CT/MR.

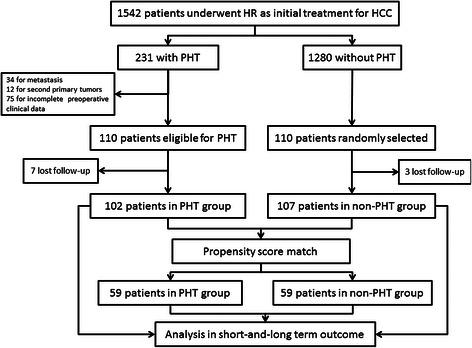

Of the 1542 patients who underwent HR as initial treatment for HCC, 231 patients were diagnosed with PHT. We subsequently excluded 34 of the 231 PHT patients for hepatic major vessel invasion, 12 for second primary tumors, and 75 for incomplete preoperative clinical data. This left 110 patients in the PHT group eligible for analysis and 110 patients without PHT were randomly selected from the remaining 1280 patients as the control group. There were seven patients in the PHT group and three patients in the non-PHT group lost to follow-up. The study ultimately enrolled 209 patients, with 102 in the PHT group and 107 in the non-PHT group (Figure 1). All the recruited patients provided written informed consent before examination and resection. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Methods

The hepatic resection strategy was detailed in our previous report [18]. Briefly, we developed a surgical plan according to tumor extent evaluated by preoperative imaging and liver function evaluated by blood biochemistry, Child-Pugh grading, and ICGR15 level. Intraoperative ultrasound was applied to guarantee complete tumor resection and to reduce major vessel injury. A Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA) was used to dissect parenchyma. To decrease intraoperative blood loss, we applied the intermittent Pringle maneuver method for the majority of hepatic resections and lowered central venous pressure to 2–4 mmHg routinely. We used blood transfusions to maintain hemoglobin at least 80–90 g/l according to the degree of bleeding and the preoperative hemoglobin level.

Postoperative complications in the first 90 days were recorded and assessed by the Clavien-Dindo classification at grades ranging from one to five, with higher grades indicating greater severity [19]. We defined postoperative liver decompensation as the presence of refractory ascites and edema, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice with total bilirubin levels above 50 μmol/l [20], renal impairment, and alteration of coagulation factors (INR above 1.50) requiring fresh transfusion. The observation and grading of complications were reviewed independently by two of the authors, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

After surgery, all patients were followed up monthly in the first 3 months, every three3 months in the first 2 years and every 3–6 months thereafter. The follow-up strategy was more intensive for patients with recurrence or metastases. Recurrence was observed by measurements of serum alpha-fetoprotein level combined with ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The treatment strategy for recurrence included repeat resection/ablation for patients with three lesions or fewer and transhepatic arterial chemotherapy and embolization (TACE) or sorafenib for patients with more than three lesions. Overall survival was calculated from the time of HR to death or last follow-up until September 2013.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized as median for continuous variable and number/prevalence for categorical variable. Continuous variables were compared by the independent samples T-test and Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Binary and ordinal categorical variable were compared by the Chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test, respectively. Logistic regression with stepwise manner (entry criterion P = 0.05 and removal criterion P = 0.1) was used to explore independent prognostic factors of postoperative outcome. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards model in a stepwise manner (entry criterion P = 0.05 and removal criterion P = 0.1) was used in multivariate analysis to explore independent prognostic factors of overall survival.

Variables with statistically significant differences between groups might have impact on the postoperative outcomes. Therefore we applied propensity score matching (PSM) analysis [21, 22] to minimize the influence of selection bias and potential confounding variables between groups. Potential covariables included in PSM included age, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, hemoglobin, albumin, total bilirubin, creatinine, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, INR, Child-Pugh score, MELD score, extent of hepatectomy, tumor size, and tumor number. PHT related variables were excluded, including white blood cell and platelet count. A one-to-one nearest neighbor matching algorithm was applied with a caliper of 0.2 [23] and without replacement. After matching, 118 patients were included in further analysis (59 in each group). Standardized mean differences were also reported for all variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Propensity Score Matching for SPSS, version 1.0 (Felix Thoemmes, Cornell University/University of Tübingen). P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of demographic and clinical variables in both groups are described in Table 1. The most frequent etiology was chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) in both the PHT and non-PHT groups (93.1% vs. 94.4%). In particular, patients in the PHT group have higher total bilirubin levels (19.5 vs. 14.6 μmol/l; P < 0.001), higher INR values (1.1 vs. 1.0; P = 0.009), longer prothrombin time (14.2 vs. 13.1; P < 0.001), longer activated partial thromboplastin time (54.1 vs. 35.4; P < 0.001), lower creatinine levels (79.7 vs. 86.2; P = 0.009), lower serum albumin levels (40.7 vs. 42.6 g/l; P = 0.006), higher Child-Pugh score (5.3 vs. 5.1; P < 0.001) and higher MELD score (8.8 vs. 7.9; P < 0.001). Patients with PHT have smaller tumors (5.3 vs. 6.5; P = 0.006). Both groups have a similar number of tumors (P = 0.575), while patients with PHT received less extensive resection.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and intraoperative characteristics of patients before and after PSM

| Variable | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-PHT (n = 107) | PHT (n = 102) | P | d | non-PHT (n = 59) | PHT (n = 59) | P | d | |

| Age (yr) | 48.5 ± 11.4 | 49.4 ± 11.2 | 0.468 | −0.080 | 48.7 ± 12.1 | 49.1 ± 10.8 | 0.561 | −0.035 |

| >65:<65 | 11:96 | 12:90 | 0.732 | −0.083 | 7:46 | 5:54 | 0.542 | 0.274 |

| Gender (male: female) | 91:16 | 85:17 | 0.734 | 0.071 | 51/8 | 49/10 | 0.609 | 0.145 |

| HBV/No-HBV | 101/6 | 95/7 | 0.707 | 0.119 | 55/4 | 53/6 | 0.509 | 0.244 |

| ALB (g/L) | 42.6 ± 4.2 | 40.7 ± 4.9 | 0.006 | 0.417 | 42.1 ± 4.3 | 42.1 ± 3.9 | 0.802 | −0.001 |

| TBil (μmol/L) | 14.6 ± 5.4 | 19.5 ± 7.3 | <0.001 | −0.766 | 16.6 ± 5.6 | 17.3 ± 5.8 | 0.611 | −0.123 |

| ALT (U/L) | 45.2 ± 24.8 | 50.6 ± 36.5 | 0.254 | −0.174 | 50.7 ± 28.5 | 47.2 ± 23.2 | 0.891 | 0.135 |

| AST (U/L) | 48.5 ± 25.3 | 51.1 ± 38.2 | 0.803 | −0.081 | 48.4 ± 19.0 | 47.9 ± 22.3 | 0.675 | 0.024 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | <0.001 | 0.626 | 6.4 ± 1.8 | 5.1 ± 2.1 | <0.001 | 0.665 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 0.402 | 0.143 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.515 | −0.133 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 138.2 ± 19.5 | 139.2 ± 19.1 | 0.776 | −0.052 | 138.3 ± 17.8 | 141.3 ± 19.2 | 0.385 | −0.162 |

| Thrombocyte (109 /L) | 189.4 ± 66.6 | 96.4 ± 42.4 | <0.001 | 1.657 | 171.4 ± 63.1 | 97.9 ± 44.6 | <0.001 | 1.3452 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 86.2 ± 19.2 | 79.7 ± 18.9 | 0.009 | 0.341 | 83.6 ± 19.2 | 80.7 ± 20.4 | 0.376 | 0.146 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 7.60 ± 2.6 | 0.663 | −1.245 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 0.376 | 0.077 |

| PT (sec) | 13.1 ± 1.2 | 14.2 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | −0.917 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | 13.8 ± 0.9 | 0.751 | −0.111 |

| APTT (sec) | 35.4 ± 5.9 | 54.1 ± 38.6 | <0.001 | −0.685 | 37.1 ± 5.6 | 37.3 ± 6.2 | 0.946 | −0.034 |

| INR | 1.00 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | −0.443 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.530 | 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh classification (A/B) | 105/2 | 99/3 | 0.957 | 0.256 | 57/2 | 59/0 | 0.476 | - |

| MELD score | 7.9 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | −0.541 | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 1.6 | 0.825 | −0.065 |

| MELD classification (<9:9–10:>10) | 84:15:8 | 57:20:25 | <0.001 | −0.547 | 42:9:8 | 41:8:10 | 0.776 | |

| Size of the tumor (cm) | 6.5 ± 3.3 | 5.3 ± 3.1 | 0.006 | 0.375 | 5.7 ± 3.2 | 5.5 ± 2.9 | 0.912 | 0.066 |

| Vascular invasion(pre: abs) | 7:100 | 15:87 | 0.055 | −0.497 | 3:56 | 9:50 | 0.068 | −0.668 |

| Adjacent tissues invasion (pre: abs) | 17:90 | 12:90 | 0.389 | 0.192 | 8:51 | 9:50 | 0.793 | −0.076 |

| Lymphatic metastasis (pre: abs) | 2:105 | 1:101 | 1.000 | 0.361 | 0 | 1:58 | 1.000 | - |

| Number of tumor (1:2:>2) | 77:15:15 | 71:11:20 | 0.575 | −0.104 | 42:7:10 | 41:8:10 | 0.870 | −0.022 |

| Extent of hepatectomy (1:2:>2) | 46:36:25 | 55:36:11 | 0.034 | 0.319 | 29:20:10 | 35:16:8 | 0.289 | 0.185 |

| Intraoperative heamorrhage > 400 ml | 25 | 28 | 0.497 | −0.119 | 8 | 16 | 0.067 | −0.476 |

| Intraoperative transfusion | 20 | 24 | 0.391 | −0.161 | 6 | 11 | 0.190 | −0.389 |

| Pringle maneuver | 85 | 76 | 0.397 | 0.154 | 50 | 46 | 0.344 | 0.249 |

Continuous variables are reported in mean and standard deviation.

d indicates standardized mean differences.

As shown in Table 2, patients in the PHT group have higher liver decompensation rates (37.3% vs. 17.8%; P = 0.002), higher postoperative complication rate (43.1% vs. 23.4%; P = 0.002) and stayed longer in hospital (12.9 days vs.12.1 days; P < 0.001), compared with those of the non-PHT group. However, the distribution of severity of postoperative complication in both groups was similar (P = 0.818); seven deaths occurred within 90 days as a result of liver failure, five in the PHT group and two in the non-PHT group. The mortality rate was similar (4.90% vs. 1.87%; P = 0.271).

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes before and after PSM

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-PHT (n = 107) | PHT (n = 102) | P | non-PHT (n = 59) | PHT (n = 59) | P | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 12.1 ± 5.3 | 12.9 ± 3.9 | <0.001 | 12.6 ± 6.1 | 12.8 ± 4.2 | 0.082 |

| Liver decompensation | 19(17.8%) | 38(37.3%) | 0.002 | 15(25.4%) | 19(32.2%) | 0.416 |

| Complication | 25(23.4%) | 44(43.1%) | 0.002 | 19(32.2%) | 23(39.0%) | 0.442 |

| Clavien-Dindo Classification | 0.818 | 0.929 | ||||

| Grade 1 | 17(15.7%) | 31(30.4%) | 12(20.3%) | 15(25.4%) | ||

| Grade 2 | 2(1.9) | 5(4.9%) | 2(3.4%) | 3(5.1%) | ||

| Grade 3 | 3(2.8%) | 3(2.9%) | 3(5.1%) | 2(3.4%) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1(0.9%) | 0 | 1(1.7%) | 0 | ||

| Grade 5 | 2(1.9%) | 5(4.9%) | 1(1.7%) | 3(5.1%) | ||

Univariate analysis (Table 3) shows that postoperative complications occurred more frequently in patients with PHT (P = 0.003), age > 65 (P = 0.043), requiring intraoperative transfusion (P = 0.021), INR > 1.20 (P = 0.044) and with a greater number of tumors (P = 0.031). Liver decompensation occurred more frequently in patients with PHT (P = 0.002), intraoperative hemorrhage > 400 ml (P = 0.050), requiring intraoperative transfusion (P = 0.003), INR > 1.2 (P = 0.017) and with a greater number of tumors (P = 0.018).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of predictive factors of postoperative complication and liver decompensation

| Variables | Postoperative complication | Liver decompensation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PSM | After PSM | Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

| Prevalence | P | Prevalence | P | Prevalence | P | Prevalence | P | |

| Age > 65y (Yes : No) | 52.2% : 30.6% | 0.043 | 50.0% : 34.0% | 0.278 | 34.8% : 26.3% | 0.394 | 25.0% : 29.2% | 0.759 |

| Gender (Male : Female) | 31.8% : 39.4% | 0.397 | 35.6% : 38.9% | 0.751 | 27.8% : 24.2% | 0.670 | 31.0% : 16.7% | 0.226 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis (HBV : Non-HBV) | 32.7% : 38.5% | 0.667 | 34.3% : 50.0% | 0.326 | 28.1% : 15.4% | 0.331 | 29.6% : 20.0% | 0.524 |

| ALB (<35 : >35) | 47.1% : 31.8% | 0.205 | 50.0% : 34.8% | 0.456 | 41.2% : 26.0% | 0.186 | 33.3% : 28.6% | 0.802 |

| TBIL (<34.2 : >34.2) | 33.3% : 0 | 0.999 | 35.6% : 0 | 0.999 | 27.5% : 0 | 0.999 | 0 : 0 | - |

| INR (<1.2 : >1.2) | 30.4% : 50.0% | 0.044 | 34.3% : 50.0% | 0.326 | 24.3% : 46.4% | 0.017 | 26.9% : 50.0% | 0.134 |

| Child-Pugh classification (A : B) | 32.4% : 60.0% | 0.217 | 35.3%: 50.0% | 0.672 | 40.0% : 27.0% | 0.523 | 0 : 29.3% | 0.999 |

| MELD (<9 : 9–10 : >10) | 31.2% : 42.9% : 30.3% | 0.746 | 36.1% : 47.1% : 22.2% | 0.460 | 24.1% : 40.0% : 27.3% | 0.359 | 27.7% : 41.2% : 22.2% | 0.941 |

| Size of tumor (<5 : >5) | 33.9% : 32.0% | 0.763 | 30.0% : 43.8% | 0.127 | 25.0% : 29.9% | 0.428 | 20.0% : 41.7% | 0.012 |

| Vascular invasion (Yes : No) | 36.4% : 32.6% | 0.724 | 42.9% : 34.6% | 0.547 | 31.8% : 26.7% | 0.613 | 35.7% : 27.9% | 0.545 |

| Adjacent tissues invasion (Yes : No) | 31.0% : 33.3% | 0.807 | 35.3% : 35.6% | 0.978 | 31.0% : 26.7% | 0.624 | 35.3% : 27.7% | 0.525 |

| Lymphatic metastasis (Yes : No) | 0 : 33.5% | 0.999 | 0 : 35.9% | 1.000 | 0 : 27.7% | 0.999 | 0% : 29.1% | 1.000 |

| Number of tumor (1 : 2 : >2) | 28.4% : 42.3% : 45.7% | 0.031 | 30.1% : 53.3% : 45.0% | 0.111 | 23.0% : 30.8% : 42.9% | 0.018 | 25.3% : 33.3% : 40.0% | 0.176 |

| PHT (Yes : No) | 43.1% : 23.4% | 0.003 | 39.0% : 32.2% | 0.442 | 37.3% : 17.8% | 0.002 | 32.2% : 25.4% | 0.417 |

| Extent of hepatectomy (1 : 2 : >2) | 28.7% : 40.3% : 30.6% | 0.496 | 28.1% : 44.4% : 44.4% | 0.099 | 23.8% : 31.9% : 27.8% | 0.439 | 21.9% : 36.1% : 38.9% | 0.088 |

| Intraoperative hemorrhage >400 ml (Yes : No) | 41.5% : 30.1% | 0.130 | 54.2% : 30.9% | 0.037 | 37.7% : 23.7% | 0.050 | 50.0% : 23.4% | 0.013 |

| Intraoperative Transfusion (Yes : No) | 47.7% : 29.1% | 0.021 | 58.8% : 31.7% | 0.036 | 45.5% : 22.4% | 0.003 | 52.9% : 24.8% | 0.022 |

| Pringle maneuver (Yes : No) | 33.5% : 31.2% | 0.767 | 35.4% : 36.4% | 0.933 | 28.0% : 25.0% | 0.687 | 29.2% : 27.3% | 0.860 |

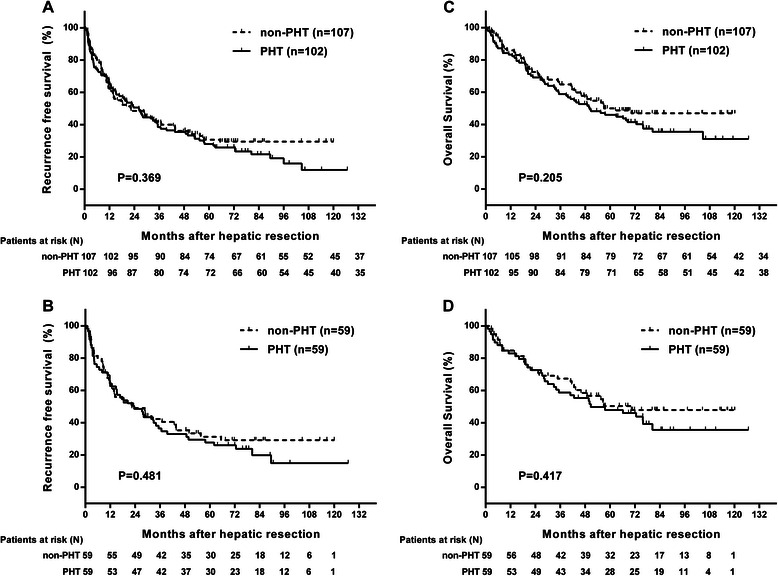

Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of PHT (Odds ratio: 2.415; 95% Confidence interval: 1.307–4.463; P = 0.050), age > 65 (OR: 2.683; 95%CI: 1.069–6.733; P = 0.036) and multiple tumor number (OR: 1.494; 95%CI: 1.013–2.203; P = 0.043) were significant predictors for postoperative complication. The presence of PHT (OR: 2.650; 95%CI: 1.375–5.110; P = 0.004), intraoperative transfusion (OR: 2.687; 95%CI: 1.293–5.584; P = 0.008) and greater number of tumors (OR: 1.495; 95% CI: 1.003–2.229; P = 0.048) were significant predictors for liver decompensation. Both groups had similar RFS rates (P = 0.369) with a median recurrence-free time of 23.57 months and similar OS rates (P = 0.205) with a median follow-up of 56.60 months. The OS rates of 1, 3 and 5 years were 82%, 59%, 46% in the PHT group and 86%, 65%, 50% in the non-PHT group, respectively. After recurrence, 19 patients underwent resection, 36 patients underwent percutaneous microwave coagulation or radiofrequency ablation, 62 patients received TACE and four patients received sorafenib treatment.

Results after propensity score matching

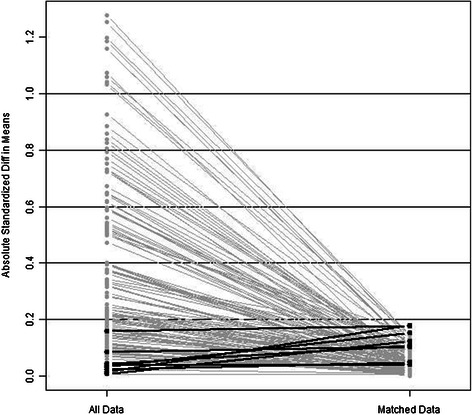

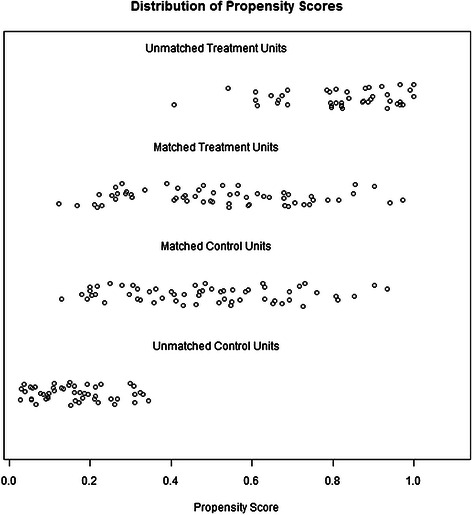

The demographic and clinical characteristics were generally similar in both groups (59 in the PHT group and 59 in the non-PHT group) after covariates had been adjusted by PSM (Table 1). The standardized difference in means and individual propensity scores of patients is shown in Figures 2 and 3. Variables that were unevenly distributed before PMS included age > 65 (P = 0.542), INR (P = 0.530), number of tumors (P = 0.870) and intraoperative transfusion (P = 0.067).

Figure 2.

Parallel line plot of the standardized difference in means before and after PSM in HCC patients with and without PHT. As the standardized difference in means was reduced, covariate balance was improved in the matched samples.

Figure 3.

Dot plot of the propensity scores of patients in the PHT and the non-PHT groups showing individual units in the dataset and whether they were matched or discarded.

The postoperative outcome after PSM matching is shown in Table 2. No significant difference in outcome was found between the two groups. Specifically, both groups had a similar length of hospital stay (12.64 vs. 12.83; P = 0.082), liver decompensation rate (25.4% vs. 32.2%; P = 0.416), postoperative complication rate (32.2% vs. 39.0%; P = 0.442) and distribution of severity of complication (P = 0.929). Four death events occurred within 90 days because of postoperative liver failure, three in the PHT group and one in the non-PHT group with similar mortality rate (5.08% vs. 1.69%; P = 0.619).

Univariate analysis in matched patients showed that postoperative complication and liver decompensation occurred more frequently in patients with intraoperative hemorrhage more than 400 ml (P = 0.037 and P = 0.013, respectively) and requiring intraoperative transfusion (P = 0.036 and P = 0.022, respectively; Table 3).

Logistic regression identified intraoperative transfusion (OR: 3.080; 95%CI: 1.075–8.828; P = 0.036) and intraoperative hemorrhage of more than 400 ml (OR: 3.273; 95%CI: 1.289–8.310; P = 0.013) as independent predictive factors of postoperative complication and liver decompensation, respectively. Both groups had similar RFS rates (P = 0.481) with a median RFS time of 23.07 months and similar OS rates (P = 0.417) with a median follow-up of 57.57 months. OS rates of 1, 3, and 5 years are 83%, 59%, 48% in the PHT group and 85%, 67%, 50% in the non-PHT group (Figure 4). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression (Table 4) identified MELD score (RR: 2.113; 95%CI: 1.242-3.593, P = 0.006), number of tumors (RR: 2.020, 95%CI: 1.192-3.424, P = 0.009), vascular invasion (RR: 2.289, 95%CI: 1.137-4.612, P = 0.020), adjacent tissues invasion (RR: 2.549, 95%CI: 1.372-4.735, P = 0.003) and intraoperative hemorrhage > 400 ml (RR: 1.849, 95%CI: 1.027-3.330, P = 0.041) as predictors for death. Importantly, PHT was not identified as a predictor for death in the post-PSM Cox regression analysis.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in HCC patients who underwent HR. (A) and (B) show recurrence-free survival in the PHT and non-PHT groups before and after PSM, respectively. (C) and (D) show overall survival between the PHT and the non-PHT groups before and after PSM, respectively.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictive factors of overall survival after PSM

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P | RR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age > 65y (Yes : No) | 0.001 | 0.982 | |||

| Gender (Male : Female) | 1.945 | 0.163 | |||

| Etiology of cirrhosis (HBV: non-HBV) | 0.001 | 0.976 | |||

| ALB (<35 : >35) | 0.018 | 0.892 | |||

| INR (<1.2 : >1.2) | 2.930 | 0.087 | |||

| Child-Pugh classification (A : B) | 1.994 | 0.158 | |||

| MELD (<9 : >9) | 3.480 | 0.065 | 2.113 | 1.242-3.593 | 0.006 |

| PHT (Yes : No) | 0.660 | 0.417 | |||

| Number of tumor (1 : >1) | 10.134 | 0.001 | 2.020 | 1.192-3.424 | 0.009 |

| Size of tumor (<5 : >5) | 5.604 | 0.018 | |||

| Vascular invasion (Yes : No) | 13.767 | <0.001 | 2.289 | 1.137-4.612 | 0.020 |

| Adjacent tissues invasion (Yes : No) | 11.552 | 0.001 | 2.549 | 1.372-4.735 | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative haemorrhage >400 ml (Yes : No) | 8.770 | 0.003 | 1.849 | 1.027-3.330 | 0.041 |

| Extent of hepatectomy (1 : >1) | 0.443 | 0.506 | |||

| Intraoperative Transfusion (Yes : No) | 2.565 | 0.109 | |||

| Pringle maneuver (Yes : No) | 0.287 | 0.592 | |||

Lymphatic metastasis is not included in analysis because there is only 1 case in 118 patients after matching.

Characteristics and outcome of unmatched patients

Forty-eight patients were excluded from the non-PHT group by PSM. These patients had a mean tumor size of 7.29 ± 3.33 cm, a CTP score of 5.04 ± 0.20, and a MELD score of 7.54 ± 1.14. There were five grade I complications, no grade II, III or IV complications, and one grade V complication, and the 1, 3, and 5 year survival rates were 88%, 63% and 49%, respectively. Forty-three patients were excluded from the PHT group by PSM. The excluded patients had a mean tumor size of 5.20 ± 3.48 cm, a CTP score of 5.54 ± 0.71 and a MELD score of 9.61 ± 1.97. Grade I, II, III, IV, and V complications occurred in 16, 2, 1, 0 and 2 cases, respectively, and the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 80%, 57% and 43%, respectively.

Discussion

In 2001, the EASL (European Association for Study of Liver) concluded that PHT was a contraindication for HR [24] based on a 29-case cohort in which HCC patients had higher risk of hepatic decompensation(73.3% vs. 0%,P < 0.0002)when PHT was diagnosed by HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg [2]. Further evidence of the impact of PHT on long-term survival, was taken from a later study which found that HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg or clinically significant PHT was an independent prognostic factor [3]. These results are supported by multiple regional studies over the past decade suggesting that HCC patients indirectly diagnosed with PHT [5-7,11] or directly diagnosed by HVPG [25,26] more frequently suffer from severe postoperative hepatic decompensation and have shorter survival. Although HVPG has a robust prognostic value [25,26], it is not routinely applied in practice because of invasiveness, high cost and patient discomfort. As a result, the EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines also suggest surrogate measurements for the diagnosis of portal hypertension, including platelet count below 100,000/mm3 associated with splenomegaly and oesophageal varices [12].

However, several other large studies [4,8-11] reported no significant difference in postoperative outcomes between PHT and non-PHT HCC patients when PHT is diagnosed with these clinical criteria. In Child-Pugh class A patients, no difference was found in postoperative mortality, morbidity [8] and survival [27] between the PHT and the non-PHT group. Similarly Cucchetti et al. reported that portal hypertension had no effect on postoperative outcome and survival as long as other prognostic variables were evenly distributed between both groups [4]. Additionally, Child-Pugh A or B patients with esophageal varices have a significantly higher 5-year overall survival rate and a similar postoperative complication rate when compared with patients without esophageal varices [9]. A further study of 434 patients found that PHT was not a prognostic factor with regard to the overall survival, and concluded that resection for HCC may also be applied to patients with PHT [10]. These reports, therefore, strongly suggest that if the liver function of HCC patients is well-preserved, postoperative outcome and survival is similar regardless of presence or absence of clinically significant PHT.

In this retrospective study, the presence of clinically significant PHT was not found to be a predictor of postoperative complication or liver decompensation in univariate and multivariate analysis when other variables were evenly distributed by PSM. The inferior postoperative outcome of PHT patients before matching may be explained by poor preoperative liver function, which may exaggerate the impact of PHT on HCC patients. After matching, both groups show similar demographic and clinical characteristics, suggesting that PSM efficiently eliminates covariates and minimizes their confounding effect, thus resulting in the similar intraoperative and postoperative outcomes. Specifically, there was no difference in the frequency or distribution of severity of postoperative outcomes. The only prognostic variables affecting the postoperative complication and liver decompensation rates were intraoperative transfusion and intraoperative hemorrhage of more than 400 ml, respectively. This observation is supported by previous studies [28-30]. HCC patients with cirrhosis are more likely to have coagulopathy, leading to a higher risk of hemorrhage and intraoperative transfusion requirement. The similar RFS and OS in both groups before and after PSM are consistent with results in previous studies [4,9,31], indicating that HCC patients may still benefit from HR regardless of presence of PHT. This result is also confirmed by multivariate analysis indicating that only lower MELD score, an advanced stage of tumor and ineffective management of intraoperative hemorrhage were prognostic factors for overall survival. With the refinement of patient selection and improvement in surgical management, especially in management of intraoperative hemorrhage, HCC patients with clinically diagnosed PHT can achieve acceptable postoperative outcome.

Although the 2012 EASL-EORTC Clinical Practice Guidelines [12] mention that portal hypertension is a valid prognostic factor in patients undergoing resection in Asia [10], most cirrhotic patients in these studies have an etiological background of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol, rather than HBV (Table 5). In contrast, HBV is the largest attributable factor (60%) for HCC [32] in Africa and East Asia, while in Europe 60–70% of cases can be attributed to the HCV infection [33]. Consideration should therefore be given to etiological differences in these regions and their influence on postoperative outcome should be evaluated. Importantly, post-resection mortality has been reported to be significantly higher in alcoholic and HCV patients than in HBV patients [34], and an improved rate of OS has been observed in HBV HCC patients compared with those with HCV [35]. Indeed, to date, few studies have been conducted in HBV prevalent regions that support recommendations of the guidelines on this issue [6, 7], with one of these pointing out that even if PHT is a powerful prognostic factor, patients with a single tumor and absence of gross vascular invasion may still experience a survival benefit from HR [7]. We therefore surmise that the recommendation made in the guidelines that PHT should be a contraindication for HR is not appropriate for all patients in these regions. The current study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study demonstrating that clinically significant PHT is neither a prognostic factor for postoperative complication nor for overall survival after HR in a hepatitis B virus prevalent region.

Table 5.

Review of etiological characteristics of patient cohorts in previous studies of PHT

| Study (year) | Patients | Etiology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | HCV | Alcohol | Others* | ||

| Nagasue et al. (1999) [36] | 63 | 16 (25.40%) | 29 (46.03%) | — | 18 (28.57%) |

| Llovet, J. M. (1999) [3] | 164 | 17 (10.37%) | 122 (74.39%) | 16 (9.76%) | 9 (5.49%) |

| Ripoll, C. (2005) [37] | 393 | 35(8.9%) | 142(36.1%) | 172(43.8%) | 44 (11.20%) |

| An M (2006) [6] | 142 | 115 (80.99%) | 6 (4.23%) | — | 21 (14.79%) |

| Capussotti, L. (2006) [8] | 217 | 43 (19.82%) | 105 (48.39%) | 62 (28.57%) | 7 (3.23%) |

| Minagawa, M. (2007) [5] | 13566 | 2682 (19.77%) | 9025 (66.53%) | 3063 (22.58%) | — |

| Kawano, Y. (2008) [9] | 134 | 29 (21.64%) | 75 (55.97%) | — | 30 (22.39%) |

| Ishizawa T (2008) [10] | 386 | 75 (19.43%) | 251 (65.03%) | — | |

| Cucchetti, A. (2009) [4] | 241 | 37 (15.35%) | 162 (67.22%) | — | 42 (17.43%) |

| Choi, G. H. (2011) [7] | 100 | 77 (77%) | — | — | — |

| Boleslawski, E. (2012) [25] | 40 | 5 (12.5%) | 30 (75%) | 5 (12.5%) | |

| Santambrogio, R. (2013) [11] | 223 | 38 (17.04%) | 135 (60.54%) | — | 50 (22.41%) |

*Others etiologies include HBV + HCV, hemochromatosis, metabolic, cholestasis and unknown factors.

Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. All patient data were obtained from a single institution. Thus, multiple-center studies will be necessary to validate our conclusions. In addition, PHT in this retrospective study was indirectly diagnosed by clinical criteria so we are still not able to address the role of HVPG measurement as the diagnostic criterion for PHT in HCC patients with HBV cirrhosis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, with respect to postoperative complication, liver decompensation, RFS and OS, clinically significant PHT should not be regarded as contraindication for HR because HCC patients in HBV prevalent region can still benefit from surgery if preoperative liver function is well-preserved and intraoperative hemorrhage is under control.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81172344, 81372571, and 81101863), the Key Project of Education Department of Guangdong Province (No. CXZD1133), Guangdong Department of Science & Technology Translational Medicine Center grant 2011A080300002, the Sun Yat-Sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (No. 2012010).

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma)

- PHT

Portal hypertension

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- ALB

Albumin

- TBIL

Total bilirubin

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- WBC

White blood cell

- RBC

Red blood cell

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- PT

Prothrombin time

- APTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time)

- INR

International normalized ratio

- MELD

Model for end stage liver disease

Footnotes

Wei He and Qingli Zeng contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WH performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. QLZ drafted and revised the manuscript. YZ and MXC contributed to study design and intellectual content. JXS and JLQ helped to performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the data. MC, RHZ, YDL, QJL and XQW acquired the data. BKL contributed to study design and critically revised the manuscript. YFY conceived of the study, critically revised and approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wei He, Email: hewei@sysucc.org.cn.

Qingli Zeng, Email: qlzkz@163.com.

Yun Zheng, Email: zhengyun@sysucc.org.cn.

Meixian Chen, Email: chenmeix@sysucc.org.cn.

Jingxian Shen, Email: shenjx@sysucc.org.cn.

Jiliang Qiu, Email: qiujl@sysucc.org.cn.

Miao Chen, Email: chen2yangwei@126.com.

Ruhai Zou, Email: zourh@sysucc.org.cn.

Yadi Liao, Email: liaoyd@sysucc.org.cn.

Qijiong Li, Email: liqj@sysucc.org.cn.

Xianqiu Wu, Email: wuxianq@sysucc.org.cn.

Binkui Li, Email: libinkui@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yunfei Yuan, Email: yuanyf@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.IARC. Available from: http://www-dep.iarc.fr: [accessed November 1st, 2011].

- 2.Bruix J, Castells A, Bosch J, Feu F, Fuster J, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic value of preoperative portal pressure. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1018–22. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(96)70070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology. 1999;30:1434–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cucchetti A, Ercolani G, Vivarelli M, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Ramacciato G, et al. Is portal hypertension a contraindication to hepatic resection? Ann Surg. 2009;250:922–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b977a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:909–22. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000254368.65878.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An M, Park JW, Shin JA, Choi JI, Kim TH, Kim SH, et al. [The adverse effect of indirectly diagnosed portal hypertension on the complications and prognosis after hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma] Korean J Hepatol. 2006;12:553–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi GH, Park JY, Hwang HK, Kim DH, Kang CM, Choi JS, et al. Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension following resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2011;31:485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capussotti L, Ferrero A, Vigano L, Muratore A, Polastri R, Bouzari H. Portal hypertension: contraindication to liver surgery? World J Surg. 2006;30:992–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawano Y, Sasaki A, Kai S, Endo Y, Iwaki K, Uchida H, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with concomitant esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1670–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9880-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Aoki T, Takahashi M, Inoue Y, Sano K, et al. Neither multiple tumors nor portal hypertension are surgical contraindications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1908–16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santambrogio R, Kluger MD, Costa M, Belli A, Barabino M, Laurent A, et al. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Child-Pugh's A cirrhosis: is clinical evidence of portal hypertension a contraindication? HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association For The Study Of The L, European Organisation For R, Treatment Of C EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qamar AA, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Burroughs AK, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical significance of abnormal hematologic indices in compensated cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berzigotti A, Gilabert R, Abraldes JG, Nicolau C, Bru C, Bosch J, et al. Noninvasive prediction of clinically significant portal hypertension and esophageal varices in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1159–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayraktar Y, Balkanci F, Uzunalimoglu B, Gokoz A, Koseoglu T, Batman F, et al. Is portal hypertension due to liver cirrhosis a major factor in the development of portal hypertensive gastropathy? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:554–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagliaro L, Spina L. The italian programme on liver cirrhosis. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1987;19:295–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Yuan Y, Chen G, He L, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. Application of tumor-node-metastasis staging 2002 version in locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: is it predictive of surgical outcome? BMC Cancer. 2010;10:535. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, Ogata S, Sauvanet A, Delefosse D, et al. The "50-50 criteria" on postoperative day 5: an accurate predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;242:824–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189131.90876.9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill J. Discussion of research using propensity-score matching: comments on 'A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003' by Peter Austin, Statistics in Medicine. Stat Med. 2008;27:2055–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25:1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10:150–61. doi: 10.1002/pst.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421–30. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boleslawski E, Petrovai G, Truant S, Dharancy S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient in the assessment of portal hypertension before liver resection in patients with cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:855–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stremitzer S, Tamandl D, Kaczirek K, Maresch J, Abbasov B, Payer BA, et al. Value of hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement before liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1752–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruzzenente A, Valdegamberi A, Campagnaro T, Conci S, Pachera S, Iacono C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension: is liver resection always contraindicated? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5083–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i46.5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Wang Z, Jiang S, Shao B, Liu J, Zhang S, et al. Perioperative allogenenic blood transfusion is associated with worse clinical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romano F, Garancini M, Uggeri F, Degrate L, Nespoli L, Gianotti L, Nespoli A, Uggeri F: Bleeding in Hepatic Surgery: Sorting through Methods to Prevent It. HPB surgery : a world journal of hepatic, pancreatic and biliary surgery 2012, 2012:169351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giannini EG, Savarino V, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, Rapaccini G, Marco MD, et al. Influence of clinically significant portal hypertension on survival after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Liver Int. 2013;33:1594–600. doi: 10.1111/liv.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belghiti J, Regimbeau JM, Durand F, Kianmanesh AR, Dondero F, Terris B, et al. Resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a European experience on 328 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kao WY, Su CW, Chau GY, Lui WY, Wu CW, Wu JC. A comparison of prognosis between patients with hepatitis B and C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing resection surgery. World J Surg. 2011;35:858–67. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0928-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagasue N, Kohno H, Tachibana M, Yamanoi A, Ohmori H, El-Assal ON. Prognostic factors after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with Child-Turcotte class B and C cirrhosis. Ann Surgery. 1999;229:84–90. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ripoll C, Banares R, Rincon D, Catalina MV, Lo Iacono O, Salcedo M, et al. Influence of hepatic venous pressure gradient on the prediction of survival of patients with cirrhosis in the MELD Era. Hepatology. 2005;42:793–801. doi: 10.1002/hep.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]