Abstract

Nuclear receptor coactivators (NCOAs) are multifunctional transcriptional coregulators for a growing number of signal-activated transcription factors. The members of the p160 family (NCOA1/2/3) are increasingly recognized as essential and nonredundant players in a number of physiological processes. In particular, accumulating evidence points to the pivotal roles that these coregulators play in inflammatory and metabolic pathways, both under homeostasis and in disease. Given that chronic inflammation of metabolic tissues (“metainflammation”) is a driving force for the widespread epidemic of obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, and associated comorbidities, deciphering the role of NCOAs in “normal” vs “pathological” inflammation and in metabolic processes is indeed a subject of extreme biomedical importance. Here, we review the evolving and, at times, contradictory, literature on the pleiotropic functions of NCOA1/2/3 in inflammation and metabolism as related to nuclear receptor actions and beyond. We then briefly discuss the potential utility of NCOAs as predictive markers for disease and/or possible therapeutic targets once a better understanding of their molecular and physiological actions is achieved.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are remarkable sensors of the external and internal environment, which encompass a complete signal transduction pathway in a single polypeptide chain. NRs bind lipophilic molecules that easily diffuse through membranes and transform their signals into changes in gene expression by acting as ligand-dependent transcription factors (TFs). Steroid hormones and metabolites acting as NR ligands mediate biological processes such as metabolic homeostasis, immunity, cognition, development, and reproduction, both under normal conditions and in disease states. NR expression ranges from selective to ubiquitous among tissues and cell types and changes with physiological state, thereby contributing to diverse and pleiotropic NR action.

NRs are modular TFs composed of three main domains: a centrally located C4-Zn-finger DNA-binding domain responsible for sequence-specific binding to DNA, a C-terminal ligand binding domain, which in the agonist-bound form gives rise to transcription activation function (AF) 2, a surface for coactivator recruitment, and an additional N-terminal regulatory domain containing ligand-independent AF 1 (1–3). Once ligand-bound, monomeric or dimeric NRs bind directly to specific palindromic or composite response elements (REs) or tether to DNA via protein:protein interactions with other DNA-bound TFs to positively or negatively regulate gene expression. NR tethering to DNA via factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP1) typically results in repression of target genes in “trans” (ie, transrepression) (for a review, see Ref. 4). NR binding to composite REs, which provide binding sites for NRs together with associated TFs, may confer activation or repression, depending on the site and specific composition of factors involved (1, 5). Transcriptional targets of specific NRs vary considerably between cell types, and although historically the analysis of NR-regulated gene expression and resulting physiological outcomes has focused on endocrine functions, a growing number of biological processes are recognized to be principally under NR control.

Among those, recent years have witnessed an increasing appreciation of the role of NRs in multiple steps of innate and adaptive immunity (6, 7). In particular, the role of NRs in homeostatic inflammatory responses and in inflammatory disorders has garnered much attention. Steroid glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and estrogen receptors (ERs) and nonsteroid metabolic peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs) and liver X receptors (LXRs) have all been implicated both in activation of genes encoding anti-inflammatory mediators and repression of proinflammatory genes (8, 9), suggesting that the NRs contribute to precise control of inflammation. This exquisite level of control is indeed critical because compromised inflammation can sensitize the host to infection, whereas excessive inflammation can result in loss of tissue function and even mortality (10).

Inflammation is a relatively nonspecific and normally protective response to infection or injury aimed to clear invading pathogens and initiate wound healing. Acute inflammation is initiated when resident cells of the innate immune system (macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) detect specific pathogen- or danger-associated molecular patterns via pattern recognition receptors (eg, Toll-like receptors [TLRs]). Sensing of these agents leads to downstream signaling events, which mainly result in the activation of effector TFs NF-κB, AP1, and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) (11). These TFs activate genes encoding inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which in turn amplify and propagate the initial inflammatory response and, if necessary, signal to adaptive immune cells (eg, lymphocytes) to initiate the development of specific immunity. Newly synthesized cytokines act in a positive feedback manner to extend the primary wave or initiate secondary waves of gene expression: TNF perpetuates and sustains NF-κB action and newly synthesized type I IFNs bind to IFN-α/β receptors to induce Janus tyrosine kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling, leading to the expression of additional IFNs and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (12, 13). Resolution of inflammation starts when macrophages release extracellular proteases, which deplete local chemokine stores and in turn reduce neutrophil infiltration (14). If local mechanisms fail to resolve inflammation, continued cytokine signaling will activate the neuroendocrine hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, triggering the production of glucocorticoids (GCs) (eg, cortisol/corticosterone) by the adrenal cortex and activation of GR, a prototypic NR, which in turn acts to contain inflammation. In addition, LXRs, PPARs, and ERs have also been reported to repress NF-κB, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), STAT, and AP-1 target genes downstream of TLR signaling (for a review, see Ref. 15).

Whereas acute inflammation is a protective response to fight off pathogens, chronic low-grade inflammation has been linked to an expanding list of human pathological conditions including coronary artery disease, stroke, and even certain types of cancer (16). In particular, obesity-induced metabolic syndrome, including insulin resistance, and type II diabetes and its associated comorbidities are driven by unresolved chronic inflammation (metainflammation) with the pivotal role of innate immune cells. A critical cell type driving low-grade inflammation is the macrophage, in which NRs exert potent immunometabolic effects. In white adipose tissue (WAT), macrophages phagocytose lipids released by dying adipocytes and, in response, produce inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-6, ultimately contributing to adipose tissue dysfunction, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance (17). A similar transformation of inflammatory macrophages into lipid-filled foam cells occurs in unstable plaques in atherosclerosis, a cardiovascular manifestation of metabolic syndrome (18). With obesity and type II diabetes rates on the rise worldwide, there has been a concerted effort to dissect the molecular mechanisms and key drivers of metabolic dysfunction as a way to identify potential therapeutic targets.

NRs, in addition to their roles in inflammation, are essential metabolic sensors and effectors that allow organisms to quickly adapt metabolic pathways to changing energy requirements. For example, PPARs (PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ) are activated by fatty acids (FAs) and integrate lipid, FA, triglyceride, and glucose metabolism. One of the major actions of PPARs is to reduce free FA levels in metabolically active tissue. PPARγ is the master switch of adipocyte differentiation and energy storage because its activation promotes the expression of FA storage genes (eg, FA binding proteins) and represses expression of FA release genes (eg, Adrb3) (19, 20). LXRs α and β, activated by oxidized cholesterol derivatives (eg, oxysterols), are central to the maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis by regulating, in a tissue-specific manner, a battery of genes involved in reverse cholesterol transport and cholesterol efflux, (eg, Abca1, Abcg5, and Apoe in hepatocytes, adipocytes, and macrophages) (21, 22). GR, as the name implies, mediates glucose as well as lipid metabolism, regulating gluconeogenesis, glucose and fat storage, and adipocyte differentiation (23, 24). Finally, estrogen-related receptors, orphan NRs for which endogenous ligands have not been identified, control FA oxidation, cellular respiration, and mitochondrial biogenesis, thus serving as global regulators of energy metabolism (25, 26). Not surprisingly, many of the same NRs that regulate inflammation are critically involved in the regulation of metabolic processes. Combined with ample evidence for a link between chronic inflammation and metabolic disorders, NRs have emerged as a key TF family that can facilitate either metabolic homeostasis or insulin resistance and have indeed been used and continue to be explored as potential drug targets for metabolic disease (1, 27, 28).

Nuclear Receptor Coactivators (NCOAs): Coregulators of NR Action

NRs do not act on their own; rather, they trigger the assembly of large multiprotein complexes composed of many coregulators that enable a physical and/or functional link between NRs and transcription machinery. Coregulators are often viewed as integrators of environmental cues that confer or modulate a specific transcriptional response to NR activation. Members of the p160 family including NCOA1/SRC1, NCOA2/TIF2/GRIP1/SRC2, and NCOA3/pCIP/ACTR/AIB1/SRC3 were identified in multiple yeast 2-hybrid screens as proteins that bound agonist-activated ligand binding domains of various NRs and functioned typically as transcriptional coactivators (29–32). In addition to NRs, p160s were later found to interact with and facilitate transcription by other TFs including β-catenin, MEF-2C, Smads, and IRFs, among others, and to serve as substrates for many kinases, phosphatases, and ubiquitination and SUMOylation enzymes (for review, see Ref. 33).

As the name of the family suggests, NCOA1/2/3 are approximately 160 kDa in size and exhibit roughly 60% similarity to each other. They are recruited to AF 2 domains of ligand-activated NRs through one of the three LXXLL motifs (where X represents any amino acid) located in a central NR interaction domain (34). NCOAs provide extensive binding platforms for the recruitment of other coregulators and histone-modifying enzymes, allowing distinct transcriptional complexes to regulate gene expression in a context-specific manner. Two C-terminal activation domains (AD1/2) recruit histone acetyltransferases cAMP response element-binding protein–binding protein (CBP) 1/p300 and pCAF to AD1 and histone methyltransferases coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1) and protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) to AD2 (35–39). An N-terminal basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH-PAS) domain houses a nuclear localization sequence and interacts with the Baf57 subunit of the SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose nonfermentable) ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex (40, 41, 42). In addition, each NCOA hosts a serine/threonine-rich region between amino acids 300 and 600, which acts as a hot spot for posttranslational modifications (PTMs).

Despite their shared overall structure, each NCOA exhibits features that make it unique. NCOAs integrate diverse upstream signals and can undergo phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, acetylation, and methylation that modulate the regulatory properties of these factors. For example, NCOA3 is phosphorylated at S543 and S505, and its dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A and pyridoxal phosphate phosphatase attenuates the interaction with and coactivation of ER (43), whereas GC-dependent phosphorylation of NCOA2 at S469, S487, S493, and S499 potentiates activation of a subset of GR targets (44). Further, methylation of the NCOA3 C-terminal region by CARM1 was shown to promote dissociation of CBP and CARM1 from NCOA3 and lead to its destabilization (45, 46). In addition, the identification of splice isoforms of NCOAs has pointed to further distinctions between the three family members. The NCOA1 mRNA is spliced to encode multiple variants, which differentially associate with various NRs (47, 48). An isoform of NCOA3 that lacks exon 3 coding for most of the bHLH-PAS domain, including the nuclear localization signal (49, 50), has been identified. Interestingly, this isoform can localize to the plasma membrane and mediate activation of peripheral enzymes (50). Posttranscriptional and posttranslational processing also contribute to NCOA diversity. Recently, an NCOA1 70-kDa biologically active fragment that is formed upon proteolytic cleavage of the full-length NCOA1 (51) has been isolated. Furthermore, not all functional domains are shared by all NCOAs: for instance, NCOA2 has a centrally located repression domain (RD) that bears no similarity to the other NCOAs or any known proteins (52).

Given that NCOA1/2/3 were cloned due to their physical and functional association with steroid receptors, the initial evaluation of their biological functions focused on endocrine and reproductive systems. Mouse studies revealed overlapping but distinct roles for these coregulators as NCOA-specific knockout (KO) mice displayed unique phenotypes and physiology. For instance, analysis of NCOA2 deficiency revealed its importance in reproductive organs and neuroendocrine pathways (53, 54). NCOA2-ablated mice of both genders were hypofertile: NCOA2 KO males exhibited disrupted spermatogenesis and NCOA2 KO females had hypoplastic placentas (53). In addition, disrupted adrenal architecture in NCOA2 KO mice led to deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (54). Similarly, NCOA3 KO female mice displayed defects in reproduction, along with delayed puberty and pronounced dwarfism (55). In contrast, NCOA1 KO mice are fertile with no obvious phenotypic abnormalities beyond retarded growth in reproductive organs and partial hormone resistance (56). Interestingly, NCOA2 was overexpressed in the brain and testis of NCOA1 KO mice, which suggests that the relatively mild phenotype of NCOA1 KO may be due to partial compensation by NCOA2 (56).

Below we discuss how the shared and unique structural and functional features of NCOAs relate to their biological activities, with an emphasis on their emerging roles in inflammation and metabolic processes. The roles of NCOAs in inflammation will be discussed as related to specific NRs with which they cooperate in inflammatory contexts. We will next describe what is known thus far about the roles of individual NCOAs in metabolic processes, highlighting the fact that the nature of specific TFs whose function is mediated by a given NCOA in many cases remains to be established.

NCOAs in inflammation

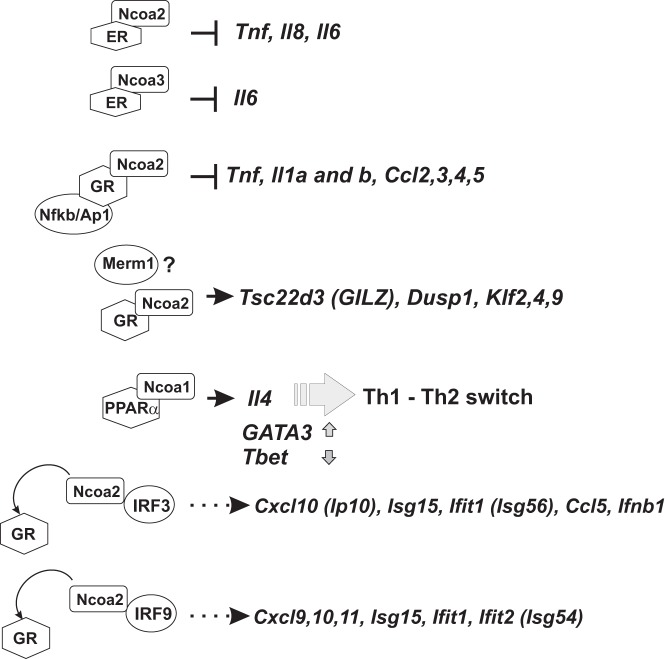

The potential role of NCOA coregulators in immune function and inflammation was first suggested by expression profiling of whole livers from mice lacking individual NCOAs that revealed deregulation of various immune-related genes (57). Given that NCOAs were first described as coregulators of the NRs, we will discuss the roles of these coregulators in inflammatory and immune responses as related to specific NRs. The specific examples discussed below are diagrammed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

NCOA transcription complexes in inflammation. NCOAs in association with NRs are involved in repression of genes encoding proinflammatory mediators (barheads) and activation of genes encoding anti-inflammatory mediators (arrowheads) via several mechanisms: direct repression by a ligand-activated DNA-bound nuclear receptor (ER with NCOA2 and NCOA3), repression via tethering sites (GR and NCOA2), direct activation by DNA-bound NR (GR and PPARα with NCOA2 and NCOA1) and competition for a limiting coactivator (IRFs and GR competing for NCOA2).

NCOAs and ERα and ERβ

Estrogens have disparate roles in inflammation and exert both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. For example, ERs have neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties in mouse models of multiple sclerosis (MS) and rheumatoid arthritis (58). Conversely, estrogen signaling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells increases the expression of inflammatory modulator TLR8, an endosomal TLR whose function has been linked to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (59). Furthermore, a striking gender disparity in susceptibility to numerous autoimmune diseases with women more likely to develop SLE, RA, MS, and Sjögren's syndrome than men by 9-, 3-, 6-, and 9-fold, respectively, potentially implicates estrogen signaling in disease pathogenesis (58); however, the exact mechanisms linking ER function to autoimmunity remain poorly understood and are likely to be disease-specific. Conversely, reflecting heightened immune system function, women are reportedly less susceptible to viral, fungal, bacterial, and parasitic infections than men (60, 61). Furthermore, in murine models of sepsis, males are more prone to morbidity and display less robust immune response than proestrus females (62).

NCOAs contribute distinct yet overlapping actions in the complex immunomodulatory capabilities of ERs. Transfection experiments with reporter constructs first pointed to a role for NCOA2 in estrogen-mediated repression (63). NCOA2 overexpression potentiated ER-mediated transcriptional repression of the Tnf promoter-derived reporter via a TNF RE in an ERα/β AF2:NCOA2 interaction- and estradiol (E2)-dependent manner in U397 monocytes (63). Subsequent chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments in U2OS osteosarcoma cells with stably integrated ER demonstrated the recruitment of endogenous NCOA2, but not NCOA1 or NCOA3, to the TNF RE after cotreatment with TNF and E2 (64). The function of NCOA2 as a corepressor of ER was corroborated by lentiviral knockdown experiments in U2OS cells showing that NCOA2 depletion led to a loss of E2 repression of TNF-induced proinflammatory targets such as Tnf and Il8 (64). Based on these cell-based experiments, it was proposed that E2-mediated repression of the Tnf gene underlies the protective properties of estrogens in TNF-induced osteoporosis (64). These studies also provided a mechanistic basis for the involvement of NCOA2 in the anti-inflammatory actions of ER; however, whether these mechanisms operate in an inflammatory disease in vivo remains to be elucidated.

Consistent with this early work, a recent study in MCF7 breast cancer and RAW264.7 macrophage-like cells showed that E2, as well as the phytoestrogen resveratrol, promoted a strong ERα:NCOA2 interaction, which led to repression of TNF-induced transcription of the Il6 gene (65). ChIP analysis revealed ERα and NCOA2/3 occupancy at the Il6 promoter in response to TNF with E2 or resveratrol cotreatment. Furthermore, knockdown of NCOA2 or NCOA3 but not of NCOA1 abolished E2- or resveratrol-dependent repression of TNF-induced IL-6 expression. One of the striking findings from this study was that ERα adopted a resveratrol-specific conformation that increased the receptor's affinity for coregulators and a preference for NCOA2 in contrast to E2-induced conformation. Indeed, the selectivity of coregulator utilization depending on NR ligands represents an exciting direction to pursue to selectively manipulate gene expression.

In addition to contributing to ER anti-inflammatory properties, NCOAs play a role in the immunomodulatory activities of ER in pathological conditions such as ovarian endometriosis and cancer. Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent condition marked by ectopic endometrium typically associated with the presence of peritoneal leukocytes and macrophages that overproduce IL-1, IL-6, TNF, and other proinflammatory cytokines and that has been associated with increased risk for endometrial cancers (66). Expression profiling of human ovarian endometriotic tissue showed high overall levels of NCOA1 and ERβ as well as an increased abundance of NCOA1- and ERβ-stained cells (67, 68). More recently, increased levels of ERα and of NCOA1 and NCOA3 in endometriotic tissue have been described (69). A role for NCOA1 in endometriosis was corroborated by a study that found a 70-kDa NCOA1 isoform overexpressed in endometriotic tissue (51). This truncated NCOA1 C-terminal fragment is generated via NCOA1 cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase 9 in a TNF-induced manner, suggesting that normally present full-length NCOA1 may be cleaved in an inflammatory context of endometriosis. Functionally, this fragment retains coactivator properties for ERβ and is able to bind pro-caspase 8 and block TNF-caspase 8–mediated apoptosis of human endometrial epithelial cells. Conversely, full-length NCOA1 promotes TNF-driven apoptosis of endometriotic cells. Thus, by facilitating ERβ functions and protecting the affected cells from apoptosis, the 70-kDa NCOA1 drives the estrogen-dependent progression of endometriosis in an inflammatory environment.

In contrast to endometriosis, in endometrial cancers the correlations between ERs and NCOA activities are less clear. Endometrial adenocarcinomas express both ER genes, but only ERα inversely correlates with inflammatory cyclooxygenase 2 (PTGS2) expression (70), perhaps suggesting that ERα may play an anti-inflammatory role in this context. Conversely, 17% of endometrial carcinomas overexpressed NCOA3, and NCOA3 mRNA levels correlated with progression of clinical symptoms and poor disease prognosis (71, 72). Given the emerging link between chronic inflammation and endometrial cancers, it is conceivable that NCOA3 deregulates immunomodulatory signaling, thereby contributing to endometrial cancer pathogenesis. Because no studies have examined the functions of both NCOAs and ERs simultaneously in the context of endometrial cancer, potential links between the two remain poorly understood.

NCOAs and GR

GCs are part of the homeostatic mechanism that controls inflammation, and their potent immunosuppressive properties have been exploited in the clinic for more than 60 years. GCs exert their effects through GR, which increases transcription of anti-inflammatory genes such as Tsc22d3 (glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper, GILZ), Klfs, and Dusp1 or represses transcription of proinflammatory targets such as Tnf and Il6 (for a review, see Ref. 73). In this context, NCOA2/GRIP1 has emerged as a prominent and unique GR coregulator. Although all p160 family members are capable of facilitating GR-mediated activation at palindromic GR elements, at which GR binds DNA directly, only NCOA2 acts as a GR corepressor when GR is “tethered” to DNA via protein-protein interactions with NF-κB or AP1 and represses their target genes (52, 74). Because NF-κB and AP1 are responsible for driving the expression of a majority of inflammatory genes in response to TLR- and cytokine-dependent signals, NCOA2 is predicted to play an important role in inflammation control. Indeed, on a global scale, nearly half of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (a TLR4 agonist)–induced genes sensitive to GR agonist dexamethasone treatment in macrophages are derepressed when NCOA2 is depleted (75). Consistently, conditional deletion (cKO) of NCOA2 in macrophages sensitized mice to LPS-induced endotoxin shock in vivo (75).

The molecular basis of NCOA2-mediated corepression is not well understood. The RD of NCOA2 was identified using mutational analysis of NCOA2 as a GR corepressor of matrix metalloproteinase 13 (Mmp13) transcription; however, the specific functions of RD remain elusive as it bears no similarity to any known protein (52). Interestingly, NCOA2 appears to engage in GR repression complexes at transcriptionally distinct classes of proinflammatory genes. It has been reported that inflammatory genes differ, depending on which step of the transcription cycle is rate limiting for their activation (for a review, see Ref. 76): for some, recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and transcription initiation is the rate-limiting step; others are occupied by transcriptionally engaged Pol II, which has initiated but paused after transcribing ∼50 nucleotides into a gene and requires a signal to be released and enter productive elongation (77, 78). Pausing is maintained by the negative elongation factor (NELF) complex and relieved by positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), which phosphorylates both Pol II and NELF, enabling NELF dissociation and Pol II release from the promoter-proximal region (79, 80). Interestingly, inflammatory genes of both classes are susceptible to GC repression (81, 82): GR:NCOA2 repress initiation-controlled genes such as Il1b by preventing LPS-induced Pol II recruitment (82); conversely, GR:NCOA2 mediate repression of elongation-controlled genes, eg, Tnf, by inhibiting P-TEFb recruitment and NELF dissociation. Importantly, GC repression of both classes of genes is attenuated in NCOA2-deficient macrophages (75, 82).

The cooperative actions of GR:NCOA2 may help explain why GCs are effective for many diseases yet are relatively ineffective for others. For example, GCs are the first-line treatment for asthma and are used to control acute inflammatory episodes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; however, innate or acquired resistance to GC therapy occurs in a relatively high number of patients rendering GCs ineffective (83, 84). Interestingly, NCOA2 overexpression in human airway smooth muscle cells helps restore GC sensitivity in IFNγ- and TNF-induced or IRF1 overexpression models of GC resistance (85). Resistance in these models arises because of accumulation of IRF1, a TF that relies on NCOA2 as a coactivator, thereby depleting it from GR transcription complexes (a detailed analysis of IRF:NCOA2 interactions appears below). Additional support for the role of NCOA2 in maintaining GC sensitivity came from a recent study in A549 lung epithelial cells showing that NCOA2 binds constitutively expressed metastasis-related methyltransferase 1 (Merm1), which rescued GR activation of an anti-inflammatory gene Tsc22d3 in an IFNγ- and TNF-induced model of GC resistance (86). Merm1 and GR co-occupied the Tsc22d3 promoter in a GC-dependent manner, making it likely that Merm1 was recruited to this transcription complex by NCOA2, although NCOA2 occupancy was not analyzed. Given these data, it is possible that NCOA2 expression is innately lower or actively reduced in inflammatory contexts and that NCOA2 levels may act as a predictive marker for development of GC resistance; therefore, careful monitoring of NCOA2 expression in inflammatory conditions may be warranted.

NCOAs and PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ

Although PPARs are primarily considered to be regulators of metabolism, their ability to modulate inflammation has been described. Because PPARs regulate FA storage and metabolism, while circulating saturated FAs themselves induce proinflammatory gene expression, p160 family members may indirectly affect inflammation by acting as PPAR coactivators at genes such as Fabps, Lpl, and Acsl5, thus promoting FA accumulation (87, 88). NCOAs were also proposed to be involved in the more direct anti-inflammatory properties of PPARs: by assisting PPARs in sequestering CBP from NF-κB and AP1 (89). Indeed, liganded PPARs can inhibit the actions of TFs such as NF-κB, NFAT, AP1, and STAT1, attenuating the expression of proinflammatory genes in T cells and macrophages (4, 90, 91), which has been linked to the antidiabetic and antiatherogenic effects of PPAR ligands (91). In that study, NCOA1 served to bridge PPARγ and CBP in response to the PPARγ-selective agonist rosiglitazone, thereby limiting access of AP1 and NF-κB to CBP and attenuating their LPS/IFNγ-induced transcriptional activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene (89). However, several models invoking competition for CBP as a means of repression were later debated because of the lack of specificity and reliance on overexpression approaches (92). More recently, PPARγ ligand–dependent repression of AP1 and NF-κB target genes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase was shown to involve stabilization of PPARγ:NR corepressor complexes at inflammatory gene promoters (93). Hence, the participation of NCOAs in such complexes appears unlikely.

Interestingly, the importance of PPAR:NCOA has been recently demonstrated in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a murine model of MS. In EAE-induced mice, treatment with a PPARα agonist, gemfibrozil, exerted neuroprotective effects by inducing an IL-4-dependent switch from a Th1 inflammatory to a Th2 anti-inflammatory phenotype in T cells (94). Using a ChIP re-ChIP assay in splenocytes from these mice, the authors reported co-occupancy of PPARα and NCOA1 at the Il4 promoter and proposed NCOA1-driven activation of the Il4 gene by PPARα. Consistently, gemfibrozil treatment resulted in increased expression of the Th2 “master regulator” TF GATA3 and reduced expression of Th1 TF T-bet. Surprisingly, the loss of NCOAs has also been linked to neuroprotection in other studies. Indeed, NCOA3 ablation attenuated EAE clinical symptoms, immune cell infiltration (macrophages and CD4+ T cells) into the central nervous system, and expression of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFNγ, TNF, and CXCL10) (95). The therapeutic effects of NCOA3 depletion may result from the increased expression of PPARβ/δ in the spinal cord of these mice. PPARβ/δ expression was especially heightened in microglia, in which PPAR action induced an alternatively activated anti-inflammatory phenotype high in Ym1 and IL-10 expression. How NCOA3 may affect PPARβ/δ levels remains unknown and requires further molecular analysis.

Atypical and non-NR–mediated mechanisms of NCOA actions in inflammation

NCOA2 and IRFs

Although NCOAs were first described as NR coregulators, there has been a growing recognition of NCOAs collaborating with numerous TFs in health and disease. One specific example is the IRFs that transduce signaling information of type I IFNs. IFNα/β are released in response to viral infection and initiate ISG expression programs that are essential for host defense (96, 97). When deregulated, however, IFNs can contribute to autoimmune disease, as in the case of SLE (98). The key transcriptional activator of the Ifnb gene is IRF3, which appears to utilize NCOA2 as a cofactor (99). The disruption of the IRF3:NCOA2 complex by depleting NCOA2 decreases IRF3 target gene induction in response to TLR3 activation. Intriguingly, in cells such as mouse macrophages in which NCOA2 expression is relatively low, GR activation results in NCOA2 sequestration from IRF3, phenocopying NCOA2 depletion effects on IRF3 target gene expression, thus illustrating another mode of GC antagonism of cytokine gene expression. Limited NCOA2 levels and the GC-dependent GR:NCOA2 physical interaction are both crucial in this antagonism because NCOA2 overexpression or disruption of the GR:NCOA2 complex with the GR antagonist RU486 reverses the inhibitory effects of GCs on IRF3-driven gene expression (99).

Interestingly, NCOA2 interaction with IRFs is not limited to IRF3; IRF1, IRF9, and IRF7 have all been reported to bind this cofactor (85, 100). In particular, the GC-sensitive association of NCOA2 with the heterotrimeric STAT1:STAT2:IRF9 complex (ISGF3) that mediates IFNβ signaling underlies the ability of GR to suppress, via NCOA2 sequestration, not only the initial Ifnb gene transcription by IRF3 in response to viral double-stranded RNA but also IFNβ-mediated secondary amplification of ISG expression (100). Thus, the ability of NCOA2 to serve as a coactivator for IRFs makes the IFN pathway in macrophages uniquely susceptible to GC-mediated inhibition unlike other cytokine signaling pathways that are largely GC resistant.

NCOA2 may also be involved in the modulation of the long-term effects of GC treatment on proinflammatory IRF3 activities. In a recent ChIP-sequencing analysis, an overnight GC exposure before LPS treatment in macrophages resulted in increased colocalization of NCOA2 and GR at IRF3-bound sites (101). These sites were also identified as GR repressed with decreased levels of histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation. Considering the ability of GCs to reprogram macrophages from inflammatory M1 to a transcriptionally distinct M2-like phenotype (102), further analysis will be required to uncouple acute occupancy and transcriptional responses to GCs from stable genome-wide changes in the enhancer landscape that occur during alternate macrophage polarization.

Nontranscriptional effects of NCOAs

Given the diversity of functions that NCOAs perform across different cell types and biological processes, it is not surprising that their actions are not limited to any one NR or TF. However, the finding that some NCOA effects do not result from altered transcriptional regulation was unexpected. For instance, it was shown that NCOA3 KO mice are sensitized to LPS-induced endotoxemia, with elevated circulating proinflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-1β and higher mortality than wild-type (WT) mice (103). Interestingly, exaggerated cytokine production in cultured peritoneal NCOA3 KO macrophages stemmed from attenuated repression of translation rather than transcription: NCOA3 was found to associate with known translational repressors, T-cell intracellular antigen-1 and T-cell intracellular antigen-related protein, and enhance their binding to 3′ untranslated region A-U–rich elements in mRNA transcripts such as that of TNF (103). Consequently, loss of NCOA3 resulted in derepression of translation of such proinflammatory transcripts, leading to uncontrolled cytokine production. Another study demonstrated that paradoxically, NCOA3 KO mice are defective in bacterial clearance despite heightened TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β expression in peritoneal fluid after Escherichia coli–induced peritonitis (104). Indeed, NCOA3 KO macrophages exhibited decreased expression of SR-A protein that aids in Fc-independent phagocytosis of microorganisms, leading to bacterial dissemination and sepsis. In addition, NCOA3 KO macrophages were more sensitive to apoptosis because of their inability to produce catalase, a key antioxidant enzyme that reduces reactive oxygen species. While counterintuitive, this result highlights roles for NCOA3 in both bacterial containment and inflammatory response even though the exact mechanisms linking NCOA3 to SR-A and catalase expression remain unknown.

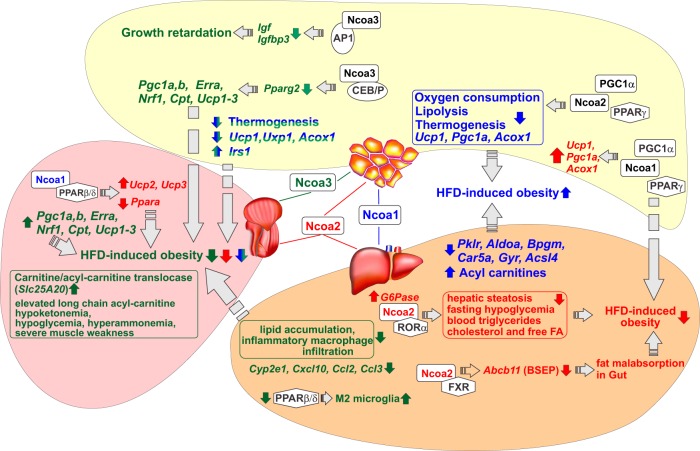

NCOAs in metabolism

Given the ubiquitous expression of NCOAs and their functional and physical interactions with NRs, it is not surprising that in addition to their roles in inflammation, the NCOAs are emerging as pleiotropic regulators of several metabolic programs (for reviews, see Refs. 105, 106). Despite the great similarity between individual family members, NCOAs generally do not compensate for each other, indicating their unique tissue- and pathway-specific roles in regulation of metabolism. Examples of the involvement of each NCOA in metabolic processes discussed below are diagrammed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Consequences of NCOA ablation in metabolic tissues. Muscle, liver, and WAT are shown in pink, orange, and yellow, respectively. NCOA1, NCOA2, and NCOA3 and the effects associated with their individual depletion are colored blue, red, and green, respectively. The effects of NCOA1/3 DKO are shown in blue and green. Depletion of NCOA2 and NCOA3 protects from HFD-induced obesity and alleviates obesity-related metabolic changes, whereas the depletion of NCOA1 exacerbates obesity-related metabolic effects in muscle, liver, and WAT. Pleiotropic changes observed in NCOA KO mice are in part mediated by NRs (shown as white hexagons), transcription cofactors (white rectangles), and several non-NR TFs (white ovals). The metabolic-related genes, whose expression is altered in NCOA KO mice, are shown in italics and the direction of change is shown by colored arrows.

NCOA1

The in vivo metabolic function of steroid receptor coactivators was first assessed in mice in which the NCOA1 gene was inactivated by gene targeting. Overall, the NCOA1 KO mice exhibit reduced oxygen consumption and lipolysis in primary adipocytes. The decreased energy expenditure in NCOA1 KO mice results in increased adiposity and a predisposition to obesity upon challenge with a high-fat diet (HFD) (107). Interestingly, in WT mice, a HFD alters the relative amount of NCOA1 and NCOA2 protein in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and WAT by increasing NCOA2 and decreasing NCOA1 expression (107). The change in the ratio of NCOA2 to NCOA1 modifies the transcriptional control of fat storage and thermogenesis by modulating transactivation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α), a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function.

It was proposed that NCOA1 and NCOA2 compete for binding to PGC1α and to PPARγ (107), a NR that controls adipogenesis and regulates FA storage and glucose metabolism (108). The lack of NCOA2 promotes the formation of stable and more active NCOA1:PGC1α complexes necessary for PPARγ recruitment to genes that regulate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, leading to an increase in energy expenditure (109). In contrast, the absence of NCOA1 favors the formation of less active NCOA2:PGC1α complexes, thereby reducing adaptive thermogenesis while increasing energy storage and adiposity (107). Thus, individual depletion of NCOA1 and NCOA2 had reciprocal phenotypes in adipose tissue. The NCOA1 and NCOA2 KO phenotypes manifest decreased and increased, respectively, transcript levels of genes involved in mitochondrial activity and FA oxidation, eg, uncoupling protein 1 (Ucp1), Pgc1a, and acyl-coenzyme A oxidase (Acox1) (107). The key question that remains to be addressed is whether or not transactivation of all these genes by PPARγ is directly controlled by NCOA1:PGC1α.

In the liver, as revealed by microarray analysis, NCOA1 ablation attenuated the expression of genes involved in energy consumption (eg, pyruvate kinase [Pklr], aldolase 1 [Aldoa], 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase [Bpgm], carbonic anhydrase 5a [Car5a], glycogenin 1 [Gyg], and acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4 [Acsl4]), which is consistent with the increased adiposity of NCOA1 KO mice (57). NCOA1 ablation altered hepatic metabolites, particularly in the fed-to-fasted state, by increasing acylcarnitines (ACs), an effect that is not observed in mice lacking NCOA2 or NCOA3. The collective increase in ACs in both liver and plasma suggests an important role for NCOA1 in regulating hepatic β-oxidation (110). In the fed-to-fasted metabolic transition, NCOA1 is also an important mediator of gluconeogenesis. Under fasting conditions, hepatic NCOA1 expression is up-regulated and induces gluconeogenesis by facilitating activation of the pyruvate carboxylase (Pc) gene by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (111). In contrast, administration of either glucose or insulin, both of which represent carbohydrate signaling molecules, decreases Ncoa1 expression and consequently that of Pc (110).

A unique property of NCOA1, not shared by NCOA2 and NCOA3, is its ability to mediate the antiobesity effects of estrogens. Estrogens suppress feeding and enhance energy expenditure, acting specifically through ERα. Those effects are largely mediated by the activation of ERα in two distinct types of hypothalamic neurons: the proopiomelanocortin neurons located in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and the steroidogenic factor-1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Histological and biochemical studies revealed that NCOA1 is abundantly expressed in both populations and interacts with hormone-activated ERα. To determine whether NCOA1 is functionally required for the antiobesity effects of estrogens, female WT and NCOA1 KO mice were ovariectomized (OVX) and then implanted with pellets containing E2 or placebo (V). OVX-V WT mice showed significant body weight gain that, as expected, was prevented in OVX-E2 WT mice. OVX-V NCOA1 KO mice showed decreased weight gain than WT mice and E2 failed to induce significant weight loss in the absence of NCOA1 (112). This result was interpreted to be a consequence of reduced food intake in both OVX-V and OVX-E2 NCOA1 KO females; it is tempting to speculate, however, that even if the NCOA1:ERα interaction is enhanced by E2, the phenotype of the OVX NCOA1 KO mice appears to be hormone independent. It will be informative to carry out a comprehensive analysis of the metabolic and behavioral genes affected by the lack of NCOA1 in the neuronal ERα signaling pathway.

NCOA2

The first metabolic profiling of NCOA2 KO mice showed a phenotype completely reciprocal to that of NCOA1 KO. Specifically, NCOA2 KO mice showed enhanced energy expenditure, protection against obesity, and increased insulin sensitivity, effects attributed to the preferential formation of the more stable and active NCOA1:PGC1α complexes (107) that drive PPARγ-mediated transactivation of genes that increase energy consumption, eg, Ucp1 (113).

More recently, NCOA2 has been shown to facilitate fasting glucose release from liver by activating glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase, encoded by the G6pc gene) expression (114). G6pc is a target for the retinoid-related orphan receptor (RORα) for which NCOA2 (and not NCOA1 or NCOA3) acts as a dedicated coactivator in this context (114). Indeed, overexpression of RORα resulted in increased expression of the endogenous G6Pase, which was abolished in the NCOA2 KO background. Furthermore, ChIP experiments showed that NCOA2 and RORα co-occupied the RORα response element region in the G6pc promoter in liver in vivo. NCOA2 ablation in mice, both in whole-body and adenovirus-mediated liver-specific contexts, resulted in a Von Gierke disease–like phenotype characterized by fasting hepatic steatosis, fasting hypoglycemia, and an increase in blood concentrations of triglycerides, cholesterol, and free FAs (114).

The NCOA2 KO mice are protected from HFD-induced obesity not only because this coactivator inhibits BAT activation, thereby promoting energy conservation (107), but also because of decreased bile acid secretion in the gut, leading to a dietary fat malabsorption (115). The molecular basis of fat malabsorption in NCOA2 KO mice is the altered expression of several hepatic transporters, including the bile salt export pump (BSEP), in NCOA2-deficient hepatocytes. The key role of BSEP in this process was corroborated by the complete reversal of malabsorption upon restoration of BSEP expression. It was previously shown that BSEP is a transcriptional target for the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) (also known as bile acid receptor) (116); NCOA2 is recruited to the Abcb11 (BSEP) promoter in a FXR-dependent manner and serves as its coactivator. This function of NCOA2 is unique among the NCOAs and is facilitated by NCOA2 phosphorylation. Although no specific phosphosites were analyzed in detail, conclusive evidence showed that these PTMs are due to AMP-activated protein kinase, an ancient energy sensor stimulated by cellular energy depletion (115).

Recently, NCOA2 has been described as coactivator of brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (BMAL1):circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), key transcription regulators of the circadian clock, in coordinating hepatic metabolism and circadian rhythm. Interestingly, NCOA2 transcript and protein vary through the day, with the highest expression early during the light phase. Consistently, NCOA2 binding to BMAL1 targets is BMAL1-dependent and highest at that time, suggesting that the increased occupancy might be a direct consequence of the increased amount of NCOA2. NCOA2 KO mice, in line with impaired BMAL1:CLOCK-mediated transactivation, have altered circadian locomotor behavior and expression of many circadian and clock-stabilizing genes (eg, Bmal1, Clock, Per1/2, Npas2, Cry1, Por, Dec1, and Dbp) as well as NR-encoding genes (eg, Nr0b2 [Shp], Esrra, Nr1d2 [Rev-erb], and Hnf4a) in the liver (117). An overlapping set of circadian and metabolic genes (eg, Por, Per1, Cry2, Dgat2, and Pnpla2) were similarly deregulated in BAT; WAT, skeletal muscle, and the heart displayed a defect in genes involved in glucose and pyruvate metabolism (Pdk4 and Pdk1) as well as lipid synthesis (eg, Fads2, Elovl6, and Dgat2) (117).

In addition to its metabolic functions in BAT, WAT, and liver, NCOA2 was reported to play important roles in energy homeostasis of skeletal muscle (118). The cKO of NCOA2 in skeletal muscle myofibers enhanced mitochondrial uncoupling and increased expression of Ucp2 and Ucp3, which correlated with increased energy consumption and protection from muscle wasting as well as resistance to obesity and diabetes upon HFD challenge. The increased energy consumption of NCOA2 cKO mice relies on NCOA1. It has been shown in differentiated C2C12 myocytes that NCOA1 is recruited to the Ucp3 promoter as a coactivator of the GW501516-activated PPARβ/δ. In contrast, overexpressed NCOA2 was recruited to these sites in the absence of ligand treatment, and GW501516 strongly attenuated this recruitment, relieving the repressive action of NCOA2 (118). As previously shown in both WAT and BAT (107), the balance between NCOA1 and NCOA2 was crucial for fine tuning the expression of metabolic genes such as Ucp3 and Pgc1a in differentiated C2C12 myocytes (118). The NCOA1-dependent induction of Ucp3 was further investigated in skeletal muscle of NCOA1/2 double-cKO mice in which the loss of NCOA1 abolished the increase of Ucp2 and Ucp3 expression observed in NCOA2 cKO mice (118). Considering the role of PPARβ/δ ligand in mutually exclusive recruitments of NCOA1 and NCOA2 to the Ucp3 promoter, it would be interesting to further investigate whether these coregulators have a broader function in controlling PPARβ activity.

Loss of NCOA2 in myocytes also resulted in decreased expression of several PPARα target genes involved in FA oxidation including Ppara itself. So far, it has been shown that NCOA2 is recruited to the Ppara promoter in primary cardiomyocytes; hence, altered expression of PPARα targets observed in NCOA2-deficient myocytes has been attributed to reduced PPARα expression. However, in light of the findings with PPARβ (118) and PPARγ (107) relying on NCOAs for function, it is likely that NCOA2 also serves as a PPARα coregulator controlling metabolic gene expression in heart. Interestingly, NCOA2 appears to be involved in several gene networks in the heart by cooperating with several nonreceptor cardiac TFs, eg, MEF2, GATA4, and Tbx5. In all three cases, (1) their expression is attenuated in the absence of NCOA2, (2) NCOA2 is recruited to the promoters of these TFs, directly regulating their expression, (3) NCOA2 interacts with them in overexpression systems, and (4) ChIP-sequencing analysis revealed an overlap between NCOA2 binding sites and those of these TFs (119). Given such extensive functional interactions of NCOA2 with PPARs and other cardiac TFs, it is tempting to speculate that NCOA2 deficiency in the heart will probably result in additional cardiac dysfunctions.

NCOA3

The first study investigating the role of NCOA3 in metabolism revealed its pivotal role in adipocyte differentiation because lipid accumulation was inhibited in cultured embryonic fibroblasts derived from NCOA3 KO mice. Consistently, the NCOA3 KO mice displayed significantly reduced body and fat weight despite their food intake and absorption or locomotor activities being similar to those of WT mice. The reduction in adiposity was specifically associated with dramatically reduced expression of the master regulator of adipocyte differentiation PPARγ2; indeed, it has been shown that expression of the Pparγ2 isoform is directly controlled by NCOA3 through cooperative interactions with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members (120). Moreover, NCOA3 KO mice show growth retardation due to reduced serum levels of IGF-1 (121), a transcriptional target of AP1:NCOA3 activation complexes, as well as its carrier, IGF-binding protein 3, which is normally up-regulated by vitamin D receptor (VDR) in an NCOA3-dependent manner (121, 122). Indeed, the role of NCOA3 as a VDR coactivator was described previously (121), and NCOA3 deficiency attenuated the expression of other VDR target genes, eg, S100g and Calb1 (calbindins D9K and 28K), Cyp24 (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase), and Cdkn1a (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1) (121). Understanding VDR action is especially timely, given recent work pointing out the unexpected role of VDR in insulin resistance in adipocytes (123). In that study, VDR (Nr1I1) emerged as a key GR target gene whose activation correlated with insulin resistance in both dexamethasone- and TNF-induced models. Furthermore, VDR and GR shared target genes Tmem176a/b, Serpina3m/n, Colq, and Lcn2 were found to promote insulin resistance, suggesting a GR-VDR feed forward loop (123). Specific coactivators at work in adipocytes were not evaluated but, conceivably, the p160 proteins facilitate VDR and GR actions in these models.

The HFD-challenged NCOA3 KO mice displayed increased basal metabolism, protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance, and increased mitochondrial function in BAT (124). Consistently, RNA transcripts of several genes involved in energy production and mitochondrial function (eg, Pgc1a, Pgc1b, Erra, and Nrf1 [nuclear respiratory factor 1], Tfam [mitochondrial transcription factor A], Cpt1 [mouse carnitine palmitoyltransferase I], Cytc [cytochrome c], and Ucp1–3) were up-regulated in the BAT and muscle of NCOA3 KO mice compared with those in WT mice (124). The gene that was most affected by the loss of NCOA3 was Pgc1a, the master regulator of mitochondrial activity that coactivates many NRs and non-NR TFs (113). Although which specific PGC1α partners are critical for the phenotype was not assessed in this study, it was shown that the absence of NCOA3 affected not only PGC1α expression but also its acetylation due to deregulated expression of the GCN5 acetyltransferase (124). Indeed, NCOA3 deletion results in reduced GCN5 expression, and, hence, accumulation of the active deacetylated PGC1α. The NCOA3 expression level is also regulated by diet composition: a HFD increases NCOA3 and GCN5 expression to promote inhibition of PGC1α and storage of energy excess in adipose tissue. Conversely, fasting decreases NCOA3 and GCN5 levels (124) while increasing the expression of the PGC1α deacetylase SIRT1 (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1), known to be regulated by caloric restriction (125), leading to PGC1α activation and increased energy expenditure.

As described for WAT (124), hepatic NCOA3 expression also increases upon HFD feeding. Loss of NCOA3 in the liver reduces lipid accumulation, inflammatory macrophage infiltration, and transcription of proinflammatory genes (eg, Cyp2e1, Cxcl10, Ccl2 [Mcp1], and Ccl3 [Mip1a]), ultimately conferring protection from HFD-induced hepatic steatosis (126).

Contrary to the NCOA3 KO phenotype, disruption of PTMs, eg, serine-to-alanine mutations in the 4 NCOA3 phosphorylation sites conserved in human and mouse, yields knock-in mice with a phenotype consistent with metabolic syndrome: increased body weight, increased adiposity, insulin resistance, and age-dependent hyperglycemia in both fasting and ad libitum feeding conditions (127). The proposed underlying mechanism responsible for such a phenotype of the NCOA3 PTM loss-of-function knock-ins was an increase in transcription and plasma levels of IGF-binding protein 3, which in turn increases IGF-1 signaling (127). Although the nature of phosphorylation-dependent NCOA3-interacting TFs remains to be determined, the idea that the PTM code of NCOAs controls distinct transcription programs in the context of metabolic genes is certainly compelling. Considering the recent discovery that NCOA2 is phosphorylated on a panel of serine residues in a GC- and GR interaction-dependent manner that potentiated GR-mediated activation of specific genes (44), it is tempting to speculate that distinct NCOA2 phosphorylation patterns triggered by other TFs preferentially affect its ability to modulate transcription of metabolic genes.

Given the reciprocal metabolic consequences of NCOA1 vs NCOA3 deletion, it is not surprising that ablation of both NCOAs (NCOA1/3 double knockout [DKO]) results in a complex phenotype bearing overlapping and distinct features relative to those of mice lacking individual NCOAs. Like NCOA3 KO, DKO confers resistance to HFD-induced obesity (128), but similar to NCOA1 KO mice (107), NCOA1/3 DKO mice exhibit decreased thermogenesis (128). In contrast to NCOA1 KO mice, however, which are prone to obesity because of reduced PPARγ activation and energy expenditure in BAT (107), the decreased thermogenesis in DKO mice is a consequence of impaired expression of PPARγ target genes involved in both adipogenesis and mitochondrial uncoupling, resulting in overall deregulation of BAT differentiation and function. Consequently, NCOA1/3 DKO mice have an increased metabolic rate, which correlates with increased food consumption in both chow and HFD conditions (128). In addition, NCOA1/3 DKO mice display elevated insulin receptor substrate 1 levels and insulin signaling both in vivo and in vitro, as shown in preadipocytes and muscle cells, and remain insulin sensitive and glucose tolerant even when challenged with HFD or upon aging (129).

Interestingly, a loss of NCOA3 revealed a metabolic signature in the skeletal muscle that was unique across the p160 family. Indeed, NCOA3 KO mice accumulate long-chain AC in the skeletal muscle in both fed and fasted states, whereas WT mice show such accumulation in the fasted state only. This metabolite accumulation stems from NCOA3 controlling the carnitine/acylcarnitine translocase (Slc25A20 [CACT]) gene expression (130). The deficiency in CACT expression in NCOA3 KO mice is accompanied not only by elevated long-chain AC but also by hypoketonemia, hypoglycemia, cardiac abnormalities, hyperammonemia, abnormal electrical discharge in the brain, and severe muscle weakness, all of which are features associated with the human disorder called CACT metabolic myopathy (130). The molecular mechanisms and TFs that control NCOA3-dependent Slc25A20 transcription remain to be determined.

Implications and Future Directions

Transcriptional coregulators of the NCOA family have emerged as key components of regulatory circuits that wire inflammatory and metabolic processes in health and disease. Their versatility and the breadth of metabolic- and immune-related TFs, including many NRs, that rely on NCOAs for function underscore the central role that these cofactors play in integrating diverse environmental cues into functional gene regulation.

Since their discovery in the mid-1990s, NCOAs have been the focus of intense research, and, indeed, much has been learned regarding their unique functions. Still, many questions await to be answered. Specifically, current knowledge of the role of NCOAs in inflammation is based primarily on studies of NRs whose actions NCOAs appear to potentiate in given experimental systems. These studies, however, have been largely limited to cell culture–based analyses of transcriptional mechanisms responsible for regulating a defined gene or gene subset in response to specific triggers. The physiological relevance of the proposed mechanisms of the function of NCOA in inflammation remains to be established using their conditional depletion in immune cell types of interest in vivo and backed by appropriate animal models of complex inflammatory diseases beyond endotoxin shock. Conversely, a surge of proposed functions of NCOAs in metabolic processes is based primarily on genetic disruption of NCOAs (individually or in combination) and analyses of the resultant phenotypes. Meanwhile, the mechanistic understanding of their coregulator properties or even the nature of TFs that partner with NCOAs at specific gene targets and impart precision and specificity to cofactor action in these contexts are only beginning to emerge. Clearly, panels of complementary approaches are required to close the gap between “molecular” and “physiological” in each instance.

Such combined system-wide approaches to deciphering the functions of NCOAs in inflammation and metabolism are ever more pressing given their potential utility as therapeutic targets. In fact, NRs have been historically a unique family of TFs whose function has been manipulated pharmacologically to treat diseases as diverse as hormone-dependent breast and prostate cancers (ER and androgen receptor antagonists), numerous autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (GCs), or metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance (PPARγ ligands and thiazolidinediones). Mechanistically, the purpose of these compounds is to facilitate or preclude NR interactions with the three NCOAs which, based on structural studies, are recruited to agonist-bound NRs in a similar fashion. It is estimated that NR ligands comprise ∼13% of the unique Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs and up to 20% of the worldwide pharmaceutical market, with GCs ranking as the most prescribed class of medications worldwide. This extreme suitability of NRs as drug targets stems from the fact that their ligands are small, typically hydrophobic, molecules that do not require sophisticated delivery systems, are relatively inexpensive to synthesize, and are easy to titrate for optimal doses. Despite their widespread use, however, serious side effects, eg, metabolic changes and osteoporosis in the case of GCs or cardiovascular complications in the case of thiazolidinediones, remain a significant problem with these medications.

As the data on the nonredundant and, in some cases, reciprocal biological properties of individual NCOAs continue to emerge, it is becoming apparent that “ideal” NR-targeting molecules should be able to selectively promote or block the interactions of given NRs with specific NCOAs and do so in a cell type–dependent manner. An additional challenge, especially as related to the involvement of NCOAs in metabolic processes, is the fact that TFs whose functions NCOAs potentiate to elicit specific regulatory outcomes are unknown and may not even be NRs. If so, the NCOA:TF interactions of interest will not be easily amenable to pharmacological manipulation.

One therapeutic avenue that remains to be explored is the manipulation of NCOA expression itself. As discussed above, NCOAs frequently lie at the intersection of antagonistic signaling pathways and their absolute or relative protein levels dictate the dominance of one transcriptional network over another and, hence, the physiological output. Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests that expression of specific NCOAs may be deregulated in disease. Meanwhile, the pathways that regulate expression of NCOAs or their cell specificity or interspecies conservation remain largely unexplored. In-depth analyses of these processes combined with expanding genome-wide association study data will be instrumental in assessing both the utility of NCOAs as therapeutic targets and the feasibility of any strategies aimed to modulate their levels.

Since their initial discovery as agonist-dependent NR coactivators, the three NCOAs have been recognized as broad, multifaceted transcriptional coregulators, each having unique molecular properties and physiological roles. A better understanding of the complex functions that NCOAs perform in homeostatic and deregulated inflammatory and metabolic pathways should reveal new regulatory checkpoints to be exploited in the design of next-generation safer therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Y. Chinenov for constructive comments on the manuscript and preparation of the figures.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 DK099087), the Department of Defense, and Rheumatology Research Foundation (to I.R.). D.A.R. is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis & Musculoskeletal & Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health (Grant T32 AR007281). M.C. is a Research Fellow of the Hospital for Special Surgery David Rosensweig Genomics Center.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AC

- acylcarnitine

- AF

- activation function

- AP1

- activator protein 1

- bHLH-PAW

- basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim

- BMAL1

- brain and muscle ARNT-like 1

- BSEP

- bile salt export pump

- CACT

- carnitine/acylcarnitine translocase

- CARM1

- coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1

- CBP

- cAMP response element-binding protein–-binding protein

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- cKO

- conditional deletion

- CLOCK

- circadian locomotor output cycles kaput

- DKO

- double knockout

- EAE

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- E2

- estradiol

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- FA

- fatty acid

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- G6Pase

- glucose-6-phosphatase

- GC

- glucocorticoid

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- IRF

- interferon regulatory factor

- ISG

- IFN-stimulated gene

- KO

- knockout

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- Merm1

- metastasis-related methyltransferase 1

- MS

- multiple sclerosis

- NCOA

- nuclear receptor coactivator

- NELF

- negative elongation factor

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- OVX

- ovariectomized

- PGC1

- peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor coactivator 1α

- Pol II

- polymerase II

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor

- PTM

- posttranslational modification

- RD

- repression domain

- RE

- response element

- ROR

- retinoid-related orphan receptor

- SLE

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TF

- transcription factor

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- VDR

- vitamin D receptor

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson JA, Laudet V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:950–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rastinejad F, Ollendorff V, Polikarpov I. Nuclear receptor full-length architectures: confronting myth and illusion with high resolution. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glass CK, Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khorasanizadeh S, Rastinejad F. Nuclear-receptor interactions on DNA-response elements. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van de Pavert SA, Ferreira M, Domingues RG, et al. Maternal retinoids control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and set the offspring immunity. Nature. 2014;508:123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors RORα and RORγ. Immunity. 2008;28:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glass CK, Ogawa S. Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang W, Glass CK. Nuclear receptors and inflammation control: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological relevance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1542–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, et al. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science. 1986;234:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Werner SL, Barken D, Hoffmann A. Stimulus specificity of gene expression programs determined by temporal control of IKK activity. Science. 2005;309:1857–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venteclef N, Jakobsson T, Steffensen KR, Treuter E. Metabolic nuclear receptor signaling and the inflammatory acute phase response. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2111–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YP. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPARγ2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Vos P, Lefebvre AM, Miller SG, et al. Thiazolidinediones repress ob gene expression via activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joseph SB, McKilligin E, Pei L, et al. Synthetic LXR ligand inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7604–7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, et al. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang M. The role of glucocorticoid action in the pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005;2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ou CY, Chen TC, Lee JV, Wang JC, Stallcup MR. Coregulator cell cycle and apoptosis regulator 1 (CCAR1) positively regulates adipocyte differentiation through the glucocorticoid signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17078–17086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bianco S, Sailland J, Vanacker J. ERRs and cancers: effects on metabolism and on proliferation and migration capacities. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;130:180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Deblois G, St-Pierre J, Giguère V. The PGC-1/ERR signaling axis in cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:3483–3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ottow E, Weinmann H. Nuclear Receptors As Drug Targets. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oñate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong H, Kohli K, Trivedi A, Johnson DL, Stallcup MR. GRIP1, a novel mouse protein that serves as a transcriptional coactivator in yeast for the hormone binding domains of steroid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4948–4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Voegel JJ, Heine MJ, Zechel C, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. TIF2, a 160 kDa transcriptional mediator for the ligand-dependent activation function AF-2 of nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:3667–3675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Torchia J, Rose DW, Inostroza J, et al. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature. 1997;387:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu J, Wu RC, O'Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:615–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker MG. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, et al. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee YH, Coonrod SA, Kraus WL, Jelinek MA, Stallcup MR. Regulation of coactivator complex assembly and function by protein arginine methylation and demethylimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3611–3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee YH, Koh SS, Zhang X, Cheng X, Stallcup MR. Synergy among nuclear receptor coactivators: selective requirement for protein methyltransferase and acetyltransferase activities. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3621–3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Voegel JJ, Heine MJ, Tini M, et al. The coactivator TIF2 contains three nuclear receptor-binding motifs and mediates transactivation through CBP binding-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:507–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen YH, Kim JH, Stallcup MR. GAC63, a GRIP1-dependent nuclear receptor coactivator. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5965–5972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Belandia B, Orford RL, Hurst HC, Parker MG. Targeting of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes to estrogen-responsive genes. EMBO J. 2002;21:4094–4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li C, Wu RC, Amazit L, Tsai SY, O'Malley BW. Specific amino acid residues in the basic helix-loop-helix domain of SRC-3 are essential for its nuclear localization and proteasome-dependent turnover. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1296–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li C, Liang YY, Feng XH, et al. Essential phosphatases and a phospho-degron are critical for regulation of SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator function and turnover. Mol Cell. 2008;31:835–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dobrovolna J, Chinenov Y, Kennedy MA, Liu B, Rogatsky I. Glucocorticoid-dependent phosphorylation of the transcriptional coregulator GRIP1. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:730–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naeem H, Cheng D, Zhao Q, et al. The activity and stability of the transcriptional coactivator p/CIP/SRC-3 are regulated by CARM1-dependent methylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:120–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feng Q, Yi P, Wong J, O'Malley BW. Signaling within a coactivator complex: methylation of SRC-3/AIB1 is a molecular switch for complex disassembly. Mole Cell Biol. 2006;26:7846–7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kalkhoven E, Valentine JE, Heery DM, Parker MG. Isoforms of steroid receptor co-activator 1 differ in their ability to potentiate transcription by the oestrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, et al. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reiter R, Wellstein A, Riegel AT. An isoform of the coactivator AIB1 that increases hormone and growth factor sensitivity is overexpressed in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39736–39741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Long W, Yi P, Amazit L, et al. SRC3Δ4 mediates the interaction of EGFR with FAK to promote cell migration. Mol Cell. 2010;37:321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han SJ, Hawkins SM, Begum K, et al. A new isoform of steroid receptor coactivator-1 is crucial for pathogenic progression of endometriosis. Nat Med. 2012;18:1102–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rogatsky I, Luecke HF, Leitman DC, Yamamoto KR. Alternate surfaces of transcriptional coregulator GRIP1 function in different glucocorticoid receptor activation and repression contexts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16701–16706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gehin M, Mark M, Dennefeld C, et al. The function of GRIP1/TIF2 in mouse reproduction is distinct from those of SRC-1 and p/CIP. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5923–5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Patchev AV, Fischer D, Wolf SS, et al. Insidious adrenocortical insufficiency underlies neuroendocrine dysregulation in TIF-2 deficient mice. FASEB J. 2007;21:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu J, Liao L, Ning G, et al. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6379–6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu J, Qiu Y, DeMayo FJ, et al. Partial hormone resistance in mice with disruption of the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) gene. Science. 1998;279:1922–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jeong JW, Kwak I, Lee KY, et al. The genomic analysis of the impact of steroid receptor coactivators ablation on hepatic metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1138–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Voskuhl R. Sex differences in autoimmune diseases. Biol Sex Differ. 2011;2(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Young NA, Wua Y, Burd CJ, et al. Estrogen modulation of endosome-associated toll-like receptor 8: an IFNα-independent mechanism of sex-bias in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immun. 2014;151:66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Markle JG, Fish EN. SeXX matters in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bernin H, Lotter H. Sex bias in the outcome of human tropical infectious diseases: influence of steroid hormones. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(suppl 3):S107–S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zellweger R, Wichmann MW, Stein S, et al. Females in proestrus state maintain splenic immune functions and tolerate sepsis better than males. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. An J, Ribeiro RC, Webb P, et al. Estradiol repression of tumor necrosis factor-α transcription requires estrogen receptor activation function-2 and is enhanced by coactivators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15161–15166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cvoro A, Tzagarakis-Foster C, Tatomer D, et al. Distinct roles of unliganded and liganded estrogen receptors in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell. 2006;21:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nwachukwu JC, Srinivasan S, Bruno NE, et al. Resveratrol modulates the inflammatory response via an estrogen receptor-signal integration network. Elife. 2014;3:e02057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kumagami A, Ito A, Yoshida-Komiya H, Fujimori K, Sato A. Expression patterns of the steroid receptor coactivator family in human ovarian endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fujimoto J, Hirose R, Sakaguchi H, Tamaya T. Expression of oestrogen receptor-α and -β in ovarian endometriomata. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Han SJ, O'Malley BW. The dynamics of nuclear receptors and nuclear receptor coregulators in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:467–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Collins F, MacPherson S, Brown P, et al. Expression of oestrogen receptors, ERα, ERβ, and ERβ variants, in endometrial cancers and evidence that prostaglandin F may play a role in regulating expression of ERα. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Glaeser M, Floetotto T, Hanstein B, Beckmann MW, Niederacher D. Gene amplification and expression of the steroid receptor coactivator SRC3 (AIB1) in sporadic breast and endometrial carcinomas. Horm Metab Res. 2001;33:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sakaguchi H, Fujimoto J, Sun WS, Tamaya T. Clinical implications of steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-3 in uterine endometrial cancers. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;104:237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rogatsky I, Zarember KA, Yamamoto KR. Factor recruitment and TIF2/GRIP1 corepressor activity at a collagenase-3 response element that mediates regulation by phorbol esters and hormones. EMBO J. 2001;20:6071–6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chinenov Y, Gupte R, Dobrovolna J, et al. Role of transcriptional coregulator GRIP1 in the anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11776–11781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rogatsky I, Adelman K. Preparing the first responders: building the inflammatory transcriptome from the ground up. Mol Cell. 2014;54:245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]