Abstract

Successful approaches to tumor immunotherapy must overcome the physiological state of tolerance of the immune system to self-tumor antigens. Immunization with appropriate variants of syngeneic antigens can achieve this. However, improvements in vaccine design are needed for efficient cancer immunotherapy. Here we explore nine different chimeric vaccine designs, in which the antigen of interest is expressed as an in-frame fusion with polypeptides that impact antigen processing or presentation. In DNA immunization experiments in mice, three of nine fusions elevated relevant CD8+ T-cell responses and tumor protection relative to an unfused melanoma antigen. These fusions were: Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A (OmpA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A, and VP22 protein of herpes simplex virus-1. The gains of immunogenicity conferred by the latter two are independent of epitope presentation by major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II). This finding has positive implications for immunotherapy in individuals with CD4+ T-cell deficiencies. We present evidence that antigen instability is not a sine qua non condition for immunogenicity. Experiments using two additional melanoma antigens identified different optimal fusion partners, thereby indicating that the benefits of fusion vectors remain antigen specific. Therefore large fusion vector panels such as those presented here can provide information to promote the successful advancement of gene-based vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Immunotherapy of cancer has appealed to scientists and clinicians as a complement or alternative to toxic and often inefficient chemotherapies. Active immunotherapy of cancer (therapeutic vaccination) has yet to register a major success despite numerous clinical trials conducted worldwide. While classical vaccines rely primarily on humoral immunological memory, the induction of cellular responses has received considerable attention in the field of cancer because tumor antigens are endogenous to malignant cells. In this regard they resemble viral epitopes, which drive CD8+ T-cell responses that are capable of clearing disease.1,2 However, because tumors lack the strong stimuli that pathogens provide to the innate immune system, their efficiency in priming the adaptive responses is relatively poor. Therefore cellular immune responses to cancer require specialized antigen-presenting cells to express, process, and present tumor antigens in a context of inflammation.

While many major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I)-restricted epitopes have been identified on tumors,3–6 most tumor antigens are unaltered self-proteins. Therefore the host’s state of immunological tolerance or ignorance remains a major difficulty in the design of cancer vaccines. Immunization strategies that overcome tolerance to self-antigens already exist.7–10 Our laboratory recently reported that a self-antigen can be engineered to encode multiple heteroclitic epitopes capable of priming naïve CD8+ T cells to recognize unaltered counterparts on tumor cells. When used as DNA vaccines, such epitope-enriched (ee) antigens elicit responses that are easily monitored and are strong enough to reject tumors.11

Beyond eliciting potent antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, genetic or DNA immunization permits rapid optimization of the vaccine through classic recombinant DNA techniques. Particle-mediated cutaneous DNA immunization by gene gun has the further advantage of directly transfecting skin dendritic cells, which perform efficiently as antigen-presenting cells after migrating to secondary lymphoid organs.12,13 Other laboratories have reported the optimization of various aspects of DNA immunization such as codon usage, choice of the promoter-driving antigen expression,14 insertion of CpG motifs,15 and co-delivery of adjuvants.16,17

In addition, fusion vectors have been described, which enhance DNA immunization against cancer.18–22 Such plasmid vectors encode tumor antigens as in-frame chimeric fusions with proteins that have various immunological characteristics, ranging from the provision of helper CD4 epitopes to the enhancement of antigen processing. Studies thus far have focused on one antigen and/or one fusion partner at a time, making it difficult to discern the optimal antigen/fusion partner pair for a given disease. Using a mouse model of melanoma, we report a comprehensive survey of nine different fusion partners applied to three distinct melanoma antigens. The partner polypeptides we chose span a variety of proposed pathways of immunoenhancement. In the interests of clinical applicability, we narrowed our choice to mechanisms that are fundamental enough to operate both in mice and humans. We further investigated the immunologic mechanisms for the most potent fusion partners revealed by our data, with results that sometimes differ strongly from observations made by others who have used different experimental systems.

RESULTS

Fusion vectors for DNA immunization against melanoma

The coding sequences of three different melanosomal glycoprotein antigens (Table 1) were inserted in a panel of nine expression vector plasmids, yielding chimeric open reading frames wherein fusion partners occupy the N-terminal moiety of each chimera. Two of these antigens are rationally epitope-enriched mouse Tyrp1 (Tyrp1ee) and human gp100 (hgp100eeA*0201), that carry engineered heteroclitic, MHC I–restricted epitopes.11 The third antigen, wild-type human gp100 (hgp100/pmel17), carries a single natural H2-Db-restricted heteroclitic tumor rejection epitope.23,24 Fusion vectors used in this study either tag the antigen directly for proteasomal degradation or direct the antigen to alternative pathways of processing and presentation through an alteration of the antigen’s intracellular fate (Table 2).

Table 1.

Melanoma antigens and derived epitopes used in this study

| Tyrp1ee | Hgp100 | Hgp100ee A*0201 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8 epitope sequence (wild-type/ heteroclitic) |

455TAPDNLGYA463/ TAPDNLGYM |

25EGSRNQDWL33/ KVPRNQDWL |

280YLEPGPVTA288/ YLEPGPVTV |

| Presenting MHC allele |

H2-Db | H2-Db | HLA-A*0201 |

| Reference | 11 | 23,24 | This study |

Table 2.

N-terminal fusion partner proteins used in this study

| Partner protein | Reported mechanism of increased immunogenicity |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Self-cleaving ubiquitin | Degradation by proteasome | 43 |

| Noncleavable ubiquitin | Degradation by proteasome | 43 |

| HIF1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) |

Degradation by proteasome | 44,45 |

| HIV Tat protein translocation domain (PTD) |

Plasma membrane crossing | 46 |

| Herpes simplex VP22 | Plasma membrane crossing | 22 |

|

Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A (OmpA) |

Dendritic cell loading via TLR2 |

47 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

exotoxin A |

Endosome-to-cytoplasm translocation (not corroborated in this study) |

21,26,48 |

| Calreticulin | ER retention; association with antigenic peptides |

20 |

|

E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin, b subunit |

Preferential MHC I epitope processing |

49 |

| Vaccine adjuvant | 50 |

Abbreviations: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MHC I, major histocompatibility class I; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2.

Fusion partners that confer gains in immunogenicity

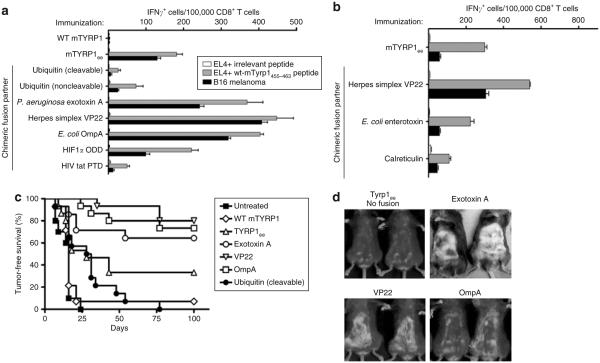

The ability of a fusion partner to enhance immunogenicity was evaluated in C57BL/6 mice that were immunized with the fused Tyrp1ee antigen. A gene gun apparatus was used for delivering DNA-coated gold particles into the epidermis of mice. Immune responses were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot, tumor rejection assays, and by assessment of autoimmune coat hypopigmentation (similar to vitiligo in humans). We observed that the frequency of epitope-specific, interferon-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells reflects the level of protection against challenge with B16 melanoma or autoimmunity (Figure 1a–d). In addition, when B16 melanoma cells served as targets in enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays instead of peptide-pulsed EL-4 thymoma cells, an identical pattern of relevant frequency of occurrence of CD8+ T cells, according to the fusion vector used, was observed (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Comparison of effects of N-terminal fusion partners on DNA vaccine immunogenicity.

(a,b) C57BL/6 mice (3 mice/group) were immunized with wild-type (WT) mTyrp1 or Tyrp1ee antigen either unfused or fused to the indicated fusion partners. CD8+ T-cell responses were quantified using interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays against the indicated targets cells (irrelevant peptide = SIINFEKL; same legend for both panels). Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD. (c) Mice (15 mice/group), immunized as indicated in a and b, were inoculated intradermally with 105 B16 melanoma cells 5 days after the last of four weekly immunizations, and tumor-free survival was monitored over time. (d) Autoimmune hypopigmentation after immunization with immunogenic fusion partners that conferred the greatest immunogenicity, as compared to immunization with the unfused antigen.

Three of nine fusion partners conferred a clear gain in immunogenicity (Figure 1c): exotoxin A from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, VP22 protein from herpes simplex virus, and outer membrane protein A (OmpA) from Escherichia coli. A mechanistic analysis of these three vaccine designs is described below.

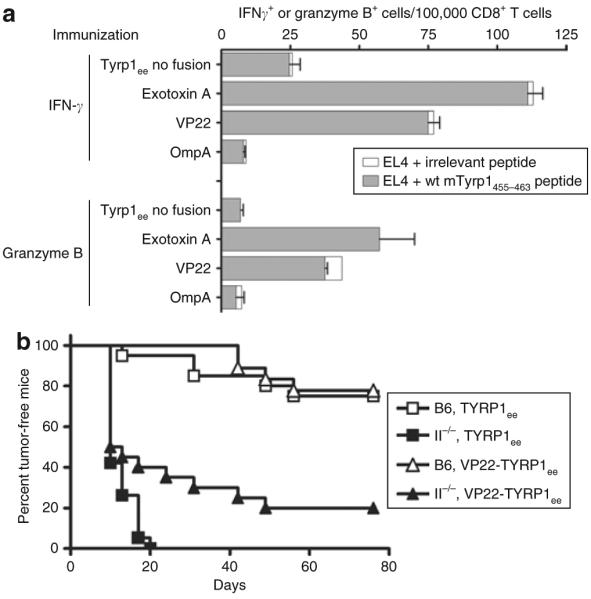

Exotoxin A and VP22 enhance CD8+ T-cell responses in an MHC II–independent manner

All three fusion partners that displayed enhanced immunogenicity are of foreign, microbial origin and are likely to contain strong epitopes that may provide immunological help. In order to determine whether the immunoenhancing effects observed here are caused by the accidental contribution of MHC II–restricted helper epitopes, we compared the immune responses of each chimeric antigen with the unfused antigen in congenic C57BL/6 mice deficient for MHC II (MHC II−/−). In all cases, CD8+ T-cell responses were weaker in MHC II−/− mice than in wild-type mice (data not shown). However, the VP22 and exotoxin A fusions elicited a higher number of peptide- and tumor-specific CD8+ T cells than the unfused antigen did (Figure 2a). These data demonstrate that the immunoenhancing effect of these two fusions is maintained even in the absence of MHC II-restricted epitope presentation. Furthermore, the VP22-TYRP1ee chimera is a strong enough immunogen to delay the growth of B16 melanoma tumors in MHC II−/− mice (Figure 2b). In contrast, responses induced by the OmpA fusion were completely abrogated in MHC II−/− mice, thereby suggesting that this fusion partner enhances immunogenicity through recruitment of CD4+ helper T cells recognizing foreign epitopes.

Figure 2. Chimeric fusion partners have different patterns of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II)-dependence for immunoenhancement.

(a) MHC II–deficient C57BL/6 mice were genetically immunized with Tyrp1ee antigen either unfused or fused to the indicated fusion partners. CD8+ T-cell responses against EL4 cells pulsed with the H2-Db restricted wild-type (WT) Tyrp1455–463 epitope (Table 1) were monitored using enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays to detect the secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or granzyme B. Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD. Spots detected against the chicken ovalbumin 257–264 (SIINFEKL) irrelevant control peptide are plotted as open boxes stacked to the right of the test peptide value bars. (b) Tumor-free survival in WT (B6) or MHC II–deficient (II−/−) C57BL/6 mice immunized with unfused or VP22-fused TYRP1ee antigen. Groups of 15 mice received a tumor challenge of 105 B16 melanoma cells 5 days after the last of four weekly immunizations.

Roles of the functional domains of P. aeruginosa exotoxin A in DNA immunization

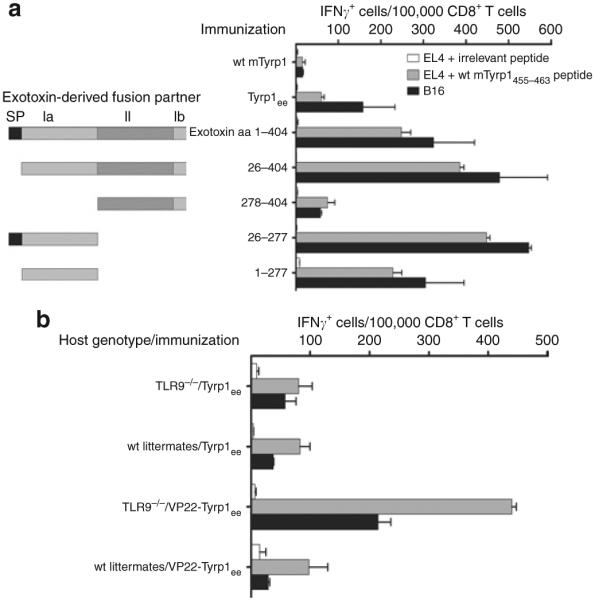

The functional domains of exotoxin A have been described earlier;25 the N-terminal domain I contributes to cell surface receptor binding, and domain II mediates membrane translocation from endocytic vesicles to the cytosol, facilitating proteasomal degradation of its cargo antigen (Table 2). The immunostimulatory properties of exotoxin A as a fusion partner have been attributed to domain II.21 The C-terminal toxic domain III is absent from our vaccine constructs as well as from those studied by others. In contrast to constructs used by others,21,26 our exotoxin fusion vector encodes the toxin’s own N-terminal signal peptide. In order to clarify the respective contributions of the various domains, we created additional exotoxin A fusion constructs, lacking the signal peptide (mature form), or domain I, or domain II (Figure 3a). Immunization experiments using these variant exotoxin constructs showed that the signal peptide and domain II are dispensable, whereas domain I is necessary and sufficient for gain of immunogenicity. It therefore follows that translocation of the exotoxin A domain II into the cytosol along with the cargo antigen does not account for increased immune responses.

Figure 3. Factors of immunogenicity for exotoxin A and VP22.

(a) Contributions of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin functional domains in immunogenicity. C57BL/6 mice (three mice/group) were immunized with the indicated constructs. All exotoxin-derived fusion partners are fused in-frame, upstream of mTyrp1ee. The exotoxin domains included in each construct are sketched and numbered to the left of the vertical axis, with the corresponding amino acid boundaries indicated directly next to the axis. SP = signal peptide; Ia = domain Ia; II = domain II; Ib = domain Ib. CD8+ T-cell responses were quantified using the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay. Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD. (b) Immunogenicity of the VP22-Tyrp1ee chimera in wild-type or TLR9-deficient (TLR9−/−) C57BL/6 mice (three mice/group) was determined. CD8+ T-cell responses were quantified using the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Irrelevant peptide: chicken ovalbumin 257–264 (SI NFEKL). Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD.

Immunogenicity and the G+C content of VP22’s coding sequence

The coding sequence of the human herpes simplex virus-1 VP22 protein has a high G+C content. We therefore examined the possibility that this DNA sequence might be recognized by the host’s innate immunity regulator, Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). We compared the immunogenicity of this vector in wild-type and in TLR9-deficient mice. CD8+ T-cell responses were not diminished in TLR9−/− mice when compared with wild-type littermates or pure-bred C57BL/6 mice (Figure 3b). In addition, TLR9−/− mice and wild-type littermates responded identically to the nonfused Tyrp1ee antigen (data not shown). It has been previously reported that TLR9−/− mice can be efficiently immunized using DNA vaccines.27 These results exclude a contribution by GC-rich elements within the VP22 DNA sequence to the immunogenicity of the VP22-Tyrp1ee vector.

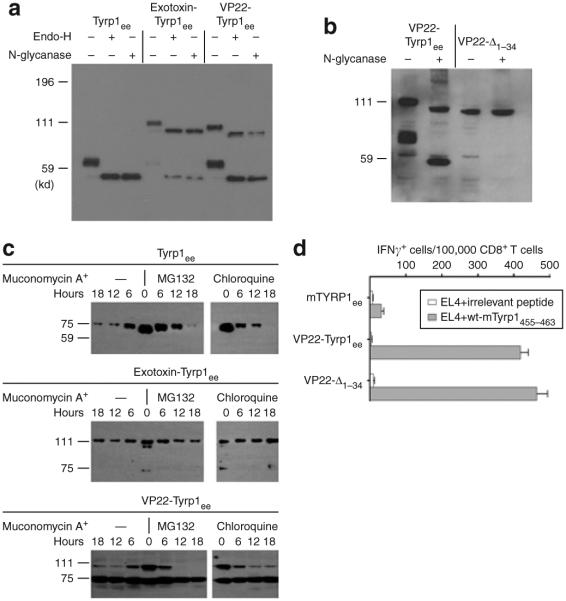

Intracellular fates of exotoxin A and VP22 chimeras

In order to understand the mechanisms of the immunogenicity conferred by exotoxin A and VP22, we compared the intracellular fate of the fusion proteins to the unfused antigen. Chimeric proteins consisting of VP22 or exotoxin A fused to the Tyrp1ee antigen acquire proximal, endoglycosidase H-sensitive glycosylation (Figure 4a), thereby confirming that the chimeric proteins are translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) despite the presence of foreign moieties at their N-terminus. Therefore, the predicted Tyrp1 signal peptide (amino acids 1–23) may still be recognized and processed through the classical cotranslational pathway despite its nonphysiological position in the chimeras. In order to confirm this, we constructed an alternative VP22 chimera lacking amino acids 1–34 of Tyrp1ee (VP22-Δ1–34). By N-glycanase digestion and Western blot analysis, it was found that this chimera failed to acquire glycosylation, thereby demonstrating that it is not translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 4b). From this finding it is clear that the presence of the signal peptide is a strict requirement for glycosylation, even in the context of a large N-terminal chimeric sequence such as VP22. Further supporting the robustness of the signal peptide recognition apparatus, a translation product indistinguishable in size from the unfused, mature Tyrp1ee antigen, is present in cells transfected with VP22-Tyrp1ee and exotoxin-Tyrp1ee (Figure 4a). However, the VP22-Δ1–34 construct failed to yield a lower-molecular-weight polypeptide (Figure 4b). Therefore this product is most likely released after signal peptidase cleaves the original chimeric proteins at the same site as it does in the native antigen. Importantly, this polypeptide does not contribute to the immunogenicity of the chimeric construct, as shown by the elevated immunogenicity of the VP22-Δ1–34 construct (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Intracellular fate of chimeric antigens.

(a–c) Intracellular fate of chimeric proteins used in this study. (a,b) COS-7 cells were transfected with the FLAG-tagged antigens indicated atop the autoradiogram, and were analyzed by Western blot 36 hours after transfection. Lysates were optionally digested with endoglycosidase H or N-glycanase as indicated. (c) Time-course study of antigen degradation. Transiently transfected COS-7 cells were treated with muconomycin A to inhibit translation, and were then incubated in the absence (—) or in the presence of MG132 or chloroquine to inhibit proteasomes or pH-dependent vesicular proteases, respectively, for the indicated number of hours. Lysates were analyzed using Western blotting. (d) Immunogenicity of a VP22-Tyrp1ee construct lacking amino acids 1–34 of Tyrp1ee (VP22-Δ1–34), as compared to that of the full-length VP22-Tyrp1ee chimera. Groups of three mice were immunized as indicated, and relevant CD8+ T-cell responses were measured using interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot. Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD. WT, wild type.

Because most of the fusion strategies tested in this study were designed to feed the antigen into the MHC I presentation pathway by favoring proteasomal degradation, the stability of the various chimeric proteins may be involved in immunogenicity. We measured stability in transfection experiments in which the fate of the chimeric proteins was monitored over time, after irreversible inhibition of protein synthesis by muconomycin A (Figure 4c). The proteasome seems to be involved in the degradation of the Tyrp1ee protein, as shown by the modest stabilization in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. While the apparent half-life of the VP22-Tyrp1ee chimera is not different, it is also unaffected by MG132, thereby indicating differences in the processing of the two antigens. In contrast, the exotoxin-Tyrp1ee chimera is more stable than the unfused antigen. There is, therefore, no clear correlation between chimeric protein stability and immunogenicity.

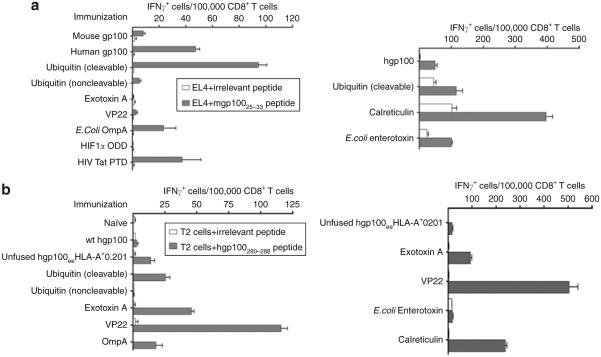

Gains of immunogenicity through chimeric strategies are antigen specific

Previous studies of fusion vectors for DNA immunization have focused on a single antigen at a time.20–22,28 In order to assess the efficacy of fusion vectors as a general approach, we tested the impact of fusion partners on two more melanoma antigens. The human gp100/pmel-17 protein encompasses a H2-Db-restricted epitope which serves as a rejection epitope against B16 melanoma in C57BL/6 mice23,24 (gp10025–). This is an example of a naturally occurring heteroclitic epitope, relative to its endogenous mouse counterpart. The immunogenicity of human gp100, as assessed by CD8+ T-cell responses to mgp10025–33, is enhanced when it is fused to calreticulin or self-cleaving ubiquitin (Figure 5a). However, neither was able to prolong tumor-free survival of mice challenged with B16 melanoma after immunization (data not shown). None of the other fusion partners conferred any positive effect.

Figure 5. Patterns of immunoenhancement by fusion partners differ according to the antigen.

C57BL/6 mice (three mice/group) were immunized with the indicated fusion constructs. Relevant CD8+ T-cell responses were measured using the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay. (a) Human gp100/pmel-17 antigen; (b) antigen which is a variant of human gp100 encoding HLA-A*0201 restricted heteroclitic epitopes; mice are transgenic for HLA-A*0201. HLA-A*0201-positive T2 human cells were used as targets cells in this assay. Error bars = mean value from triplicate wells ± SD. WT, wild type.

The third antigen used in this study, a variant of human gp100 encoding HLA-A*0201-restricted heteroclitic epitopes, was engineered for clinical use in melanoma patients (hgp100eeA*0201). In order to validate the ability of these epitopes to be processed and then presented by the HLA-A*0201 MHC I molecule, we immunized HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice with the antigen alone or as chimeric fusions. Fused versions of this antigen displayed yet another pattern of immunoenhancement, with clear positive effects from calreticulin, VP22, and exotoxin A, and none from OmpA, and heat-labile enterotoxin (Figure 5b).

DISCUSSION

For decades, prophylactic vaccines based on whole microorganisms have succeeded by inducing humoral responses and maintaining them over long periods of time. Contemporary challenges to health, such as cancer and AIDS, require the development of entirely different types of vaccines, for several reasons. First, the antigenic potential of these diseases is largely invested in determinants recognized by CD8+ T cells. Second, vaccines against these diseases will have to be therapeutic, especially in cancer. These two notions are linked, as CD8+ T cells recognize epitopes originating from within their cellular targets (foreign epitopes synthesized de novo after infection by a pathogen, or self-epitopes in the case of cancer). The development of vaccines specifically designed to engage CD8+ T cells is relatively new. Among other things, the recent progress in understanding immunological adjuvants have raised hopes of obtaining viable CD8-driven vaccines.29

Intense efforts to improve vaccines are still underway. DNA vaccines are well suited for exploring ways to harness CD8+ T cells for therapy by means of the unlimited and rapid manipulations that can be imposed on antigens through their coding DNA sequences. In this study, we sought to explore and understand one particular approach; the use of fusion vectors that deliver the antigen of interest in the form of chimeric proteins. To our knowledge, no other large panel of vectors has been tested systematically or applied to multiple antigens (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of immunogenicities according to antigen and fusion partner

| Tyrp1ee | hgp100 | hgp100ee A*0201 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Antigen target |

B16 melanoma |

wt mTyrp1 455–463 | wt mTyrp1 481–489 | wt mTyrp1 522–529 | wt mgp10025–33 | wt h100 154–162 | wt h100 280–288 | |

| Fusion partner | ||||||||

| Cleavable ubiquitin |

1.0 (2) | 0.9 (3) | 0.9 (3) | 0.7 (3) | 2.0 (6) | 0.08 (1) | 1.8 (1) | |

| Noncleavable ubiquitin |

0.4 (2) | 1.0 (3) | 0.8 (3) | 0.8 (3) | 1.5 (5) | 0.5 (1) | 0.03 (1) | |

| Pseudomonas

exotoxin A |

27.9 (7) | 4.0 (8) | 3.8 (7) | 12.7 (7) | 0.4 (5) | 5.4 (2) | 3.5 (2) | |

| Outer membrane protein A (Escherichia coli) |

7.2 (7) | 2.6 (8) | 3.2 (6) | 5.7 (6) | 0.6 (5) | 3.2 (1) | 1.3 (1) | |

| VP22 | 11.3 (9) | 7.0 (10) | 5.9 (7) | 6.0 (7) | 1.06 (4) | 10.2 (2) | 6.5 (3) | |

| Rabbit calreticulin |

1.7 (2) | 1.4 (2) | n.d. | n.d. | 5.7 (2) | 1.2 (1) | 1.4 (2) | |

| Heat-labile enterotoxin (E. coli) |

0.9 (2) | 0.9 (2) | n.d. | n.d. | 1.3 (2) | 1.2 (1) | 0.3 (1) | |

| HIV Tat translocation domain |

2.3 (2) | 2.9 (3) | 1.2 (3) | 1.2 (3) | 0.7 (5) | n.d. | n.d. | |

| HIF1α degradation domain |

0.7 (2) | 0.9 (3) | 0.8 (3) | 0.8 (3) | 1.4 (5) | n.d. | n.d. | |

Abbrevations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; n.d. not determined; WT, wild type. Values = mean fold increase in interferon-γ spots; values in parentheses represent number of experiments.

Foreign proteins such as those studied here are probably immunogenic, and the responses they elicit, MHC II–restricted CD4+ responses in particular, may provide a boost to those concomitantly directed against the antigen of interest. However, this mechanism may not operate in the context of all, or even most, MHC alleles of an outbred population such as humans. For example, exotoxin A may contain epitopes presented by HLA-DR3 but not HLA-DR52.

Therefore, for the purposes of broad clinical application, we focused on the design of a fusion vector that enhances CD8+ T-cell responses, independent of such “accidental” contributions from the chimeric partner’s amino acid sequence. In this study we addressed this concern by testing immunoenhancing fusions in mice that do not present peptides on MHC II. We found that the immunoenhancement conferred by OmpA is entirely dependent on MHC II presentation. Thus, OmpA offers no guarantee of cross-species applicability. The clinical use of MHC II–dependent fusion partners in DNA vaccination against cancer has been specifically advocated by others.30 However, a requirement for these fusion partners is that they must contain MHC epitopes relevant to the HLA allele(s) of interest.

OmpA exerts its effect on the Tyrp1ee epitopes but not on either of the two other antigenic variants of hgp100 (Figure 5, Table 3). This suggests a hierarchy of mechanisms, with helper epitopes not being sufficient in all cases. In contrast to OmpA, exotoxin A and VP22 effectively enhance CD8+ T-cell responses in MHC II–deficient mice. We argue that these vectors may successfully induce immune responses when the CD4+ compartment is deficient, such as in the elderly, patients undergoing chemotherapy, and AIDS patients. Whether exotoxin A or VP22 also allows memory CD8+ T cells to be generated in such individuals remains to be determined.

We further investigated VP22 and exotoxin A. The actual ability of the VP22 protein to circulate freely from transfected to untransfected cells (Table 2) is both the reason for its use in DNA vaccines and the topic of an extensive debate.22,31–35 Our data strongly support the value of VP22 as a fusion partner. We have tested and ruled out two possible mechanisms of immunoenhancement by VP22: accidental helper epitopes and activation of the host’s TLR9 receptor by the GC-rich VP22 coding sequence.

Unexpectedly, the membrane-translocating domain II of exotoxin A is completely dispensable for immunogenicity (Figure 3). Therefore, our results contradict the rationale for its use in previous studies. Rather, immunogenicity is entirely dependent on the toxin’s domain I, which mediates cell surface binding through the α2-macroglobulin receptor.36 The reason for this discrepancy between our results and those of others is unclear, but may illustrate that chimeric proteins behave differently depending on the nature of the cargo antigen.

We compared the degradation kinetics of the unfused Tyrp1ee antigen with those of the VP22-Tyrp1ee and exotoxin-Tyrp1ee chimeric proteins. The exotoxin-Tyrp1ee polypeptide is much more stable than the unfused antigen (Figure 4), contradicting the notion that exotoxin A constitutively feeds its cargo antigen into the proteasomal degradation pathway (Table 2). Furthermore, fusing the Tyrp1ee antigen to ubiquitin failed to enhance its immunogenicity and had only a very modest effect on hgp100 and hgp100eeA*0201 (Figure 5), while the highly immunogenic Tyrp1ee-VP22 chimera has an unaltered degradation kinetic (Figure 4). These observations suggest that the stability or instability of the antigen is not a determining factor of the potency of the vaccine. Greater stability will result in higher antigen levels in transfected cells at a steady state. This can, in turn, exert a mass-action law effect on the quantity of epitopes that are ultimately presented at the cell surface.37

The VP22-Tyrp1ee and exotoxin-Tyrp1ee constructs give ris not only to the expected chimeric proteins, but also to the mature Tyrp1ee polypeptide itself (Figure 4a). The presence of the Tyrp1 signal peptide is required for this purpose, thereby indicating that cellular signal peptidase accesses its cleavage site even though it is far from the N-terminus in the chimeric protein. In addition, the VP22 chimera failed to be translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum in the absence of signal peptide, as assessed by its lack of glycosylation. Importantly, the VP22-Δ1–34 construct, which does not yield the mature Tyrp1ee polypeptide, retained full immunogenicity. Therefore the mature Tyrp1ee polypeptide generated from the intact VP22 chimera most likely does not contribute to its immunogenicity (Figure 4d). The half-life of this product is significantly greater than that of the full-length chimera (Figure 4c), thereby suggesting that its release by signal peptidase must occur very early after its biosynthesis or even cotranslationally. Collectively, these observations attest to the functional robustness of the signal peptide processing apparatus despite the aberrant positioning of its substrate within chimeras.

The optimal fusion vector varied depending on the antigen. We speculate that an epitope’s native context may override the effects of certain fusion partners. The hgp100/hgp100eeA*0201 antigen pair addresses this question. The immunoenhancement pattern is different for the two respective epitopes of these antigens; one epitope is at the N-terminal end of the mature gp100 protein while the HLA-A*0201-restricted peptide is internal (Table 1). Conversely, in the Tyrp1ee antigen system, two epitopes located within 80 amino acids of Tyrp1455-463 followed an identical pattern (data not shown).

The exact immunoenhancing mechanisms of exotoxin and VP22 are still unclear. In the light of this work, we predict that both designs retain applicability in multiple species. Further animal studies, perhaps in a veterinary setting,38 should allow proper validation of these conclusions. There are many parameters that will have to be optimized systematically in order to generate therapeutic vaccines for cancer. This work is an attempt at covering a large array of options for one such parameter. The progress reported here may now be utilized when addressing different issues, such as the choice of adjuvant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). HLA-A*0201/Kb transgenic mice were obtained from Dr. Linda Sherman39,40 and were bred and phenotyped for HLA-A*0201 expression by flow cytometry. Congenic MHCII–deficientmice (ABBN12-M) and control C57BL/6 mice were from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). TLR9-deficient mice were obtained from Dr. Eric Pamer and bred into the C57BL/6 background for 10 generations, yielding TLR9-deficient and control wild-type littermates. All the mice were entered into experiments between 8 and 10 weeks of age. The care of all the mice used in the experiments was as per a protocol and in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Peptides

All peptides were synthesized and purified using high performance liquid chromatography to >80% purity by GeneMed Synthesis (San Francisco, CA). The peptides used were: Tyrp1455-463 (TAPDNLGYA, Db-restricted); A463M mutant (TAPDNLGYM); Tyrp1484-489 (IAVVAALLL, Db); A485N mutant (IAVVNALLL); Tyrp1522-529 (YAEDYEEL, Kb); E524Y mutant (YAYDYEEL); human gp10025–33 (KVPRNQDWL); mouse gp10025–33 (EGSRNQDWL, Db); OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL, Kb); influenza virus nucleoprotein NP (ASNENMETM, Db); influenza virus matrix protein MP58–66 (GILGFVFTL, HLA-A*0201-restricted); human gp100 peptides (HLA-A*0201): hgp100154–162 (KTWGQYWQV); T155L mutant (KlWGQYWQV); hgp100280–288 YLEPGPVTA; A288V MUTANT (YLEPGPVTv).

Plasmid constructs and site-directed mutagenesis

Classic recombinant DNA techniques were used for generating all the plasmid constructs used in this study. Site-specific mutagenesis of mouse Tyrp1 for epitope enrichment has been described earlier.11

The Hgp100 complementary DNA was similarly mutated, using reiterations of the Quickchange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), to generate the following point mutations: T155L, A273Y, I602Y, R619Y, M178Y, S570Y, T210L, A288V, and C647V. The pCRAN multiple cloning site variant of pCR3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), that has been described elsewhere,11 served as the parental backbone for all Tyrp1 fusion constructs. In all the Tyrp1 fusion vectors, open reading frames for N-terminal fusion partners were cloned and inserted in pCRAN immediately upstream of the AscI site, which is positioned so that the reading frame remains open downstream of the fusion partner into the antigen-coding sequence.

Different Tyrp1 fusion vectors were constructed: (i) Full-length mouse ubiquitin complementary DNA was obtained by reverse transcriptase PCR and cloned into pCRAN as a BamH1–AscI fragment. Subsequently, an oligonucleotide duplex encoding N-end rule degradation patterns was cloned in the AscI site, yielding the pUB1 vector from cleavable ubiquitin. The amino acid sequence of the junction region reads … RLRGGRGKEQEMATAASSGKKK (underlined = ubiquitin residues 72–76; italicized = N-end rule elements; bold = mouse actin spacer). (ii) The downstream PCR primer specifies a G–V mutation at position 76 (amino acid sequence …RLRGVRGKE…). The PCR product was cloned into pCRAN as a BamH1–AscI fragment, yielding the pUB2U vector from noncleavable ubiquitin; (iii) P. aeruginosa exotoxin A was cloned by PCR from P. aeruginosa genomic DNA. The PCR product, encoding amino acids 1–404 of the immature exotoxin A polypeptide (signal peptide included), was cloned HindIII–AscI into pCRAN. Further vectors were constructed, lacking, respectively, the exotoxin’s signal peptide, domains Ia, II, and Ib, or the signal peptide and domains II and Ib; (iv) The herpes simplex virus-1 VP22 open reading frame was excised from the plasmid pVP22Myc/ His (Invitrogen) and subcloned between the HindIII and EcoRV sites of pCRAN, yielding the pVIP vector; (v) E. coli OmpA was cloned by PCR from E. coli genomic DNA. The PCR product was cloned EcoRI–AscI into pCRAN. A flexible GSGSG linker was subsequently added by cloning an oligonucleotide duplex in the AscI site downstream of ompA; (vi) An oligonucleotide duplex encoding the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain was cloned BamH1–AscI into pCRAN. A flexible GSGSG linker was subsequently added as described earlier; (vii) An oligonucleotide duplex encoding the protein translocation domain of human immunodeficiency virus tat, followed by a flexible GSGSG linker, was cloned EcoRI–AscI into pCRAN; (viii) The coding sequence of a plasmid encoding rabbit calreticulin (kindly provided by Dr. TC Wu) 20 was reamplified using ad hoc primers The resulting PCR product was cloned into pCRAN as a HindIII–AscI fragment; and (ix) Subunit B of the heat-labile enterotoxin from E. coli was reamplified from plasmid EWD299 (American Type Culture Collection #37218, Manassas, VA). The resulting PCR product was cloned into pCRAN or pNORAA as a HindIII–AscI fragment.

All parent fusion vectors were checked by sequencing. Final constructs were obtained by subcloning the wild-type or epitope-enriched Tyrp1 antigens as AscI–NotI or AscI–XbaI fragments in frame with each fusion partner.

The pING cloning vector had been earlier developed for clinical trials.38 In order to obtain preclinical/clinical fusion vectors, all fusion partners used in the Tyrp1 constructs were subcloned into pNORAA, a pING derivative containing an AscI site, so as to allow the in-frame cloning strategy. The resulting constructs received wild-type or epitope-enriched Hgp100 as an AscI–NotI fragment, to yield the final in-frame fusion constructs.

Transfection experiments

Tyrp1 and Tyrp1ee variants containing a C-terminal FLAG tag were constructed and subcloned into the fusion vectors described above. 1–2 × 105 COS-7 cells were transfected with each FLAG-tagged Tyrp1 variant, using Fugene 6 reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Twenty four hours after transfection, the cells were treated for 1 hour with muconomyin A (0.6 µmol/l; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After being washed, the cultures were prolonged either without further treatment or in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (20 µmol/l; Sigma-Aldrich), or chloroquine (40 µmol/l; Sigma-Aldrich), or 20 mmol/l ammonium chloride. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 12.5 mmol/l Tris pH 7.5, 1.25% Triton X-100, 190 mmol/l NaCl for 30 minutes on ice in the presence of an EDTA-free cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The protein content of cell lysates was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples were normalized according to protein content and analyzed using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with peroxidase-conjugated M2 anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Endoglycosidase H-and N-glycanase analysis

Twenty-four hours after transfection, lysates from 2 × 105 COS-7 cells that had received no inhibitor treatment were digested for 5 hours with 0.005 units of endoglycosidase H or N-glycanase (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C. Samples were then analyzed using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Immunizations

Genetic immunization with DNA-coated gold particles was performed using a gene gun provided by PowderMed (Oxford, UK), as described earlier.9,41 Four injections (400–600 pounds/inch2) were administered to each mouse, one in each of the abdominal quadrants, amounting to a total of 4 µg plasmid DNA/mouse/week for 4 weeks.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays

IP-Multiscreen plates (Millipore, Burlington, MA) were coated with 1µg anti-mouse interferon-γ antibody (clone AN18; MabTech, Mariemont, OH) in phosphate-buffered saline overnight at 4 °C. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline, the plates were blocked with Rosewell Park Memorial Institute medium containing 7% fetal bovine serum for 2 hours at 37 °C. CD8+ T cells, purified using the MACS system (Myltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), were plated at a density of 105cells/well. As targets, 5 × 104 irradiated EL-4 cells or HLA-A*0201-positive human T2 lymphoma cells pulsed with 10 µg/ml peptide were added to each well. After 20 hours at 37 °C, spot development and quantification were performed as described42 using biotinylated antibody against mouse interferon-γ (clone R4-6A2; MabTech) or granzyme B (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Tumor challenge

These experiments were carried out in B16 melanoma cells as described earlier.9 The mice were injected with 105 B16F10 melanoma cells 5 days after the last immunization. The cells were injected into the shaved right flank of each mouse. Tumor growth was monitored three times a week using Vernier calipers. Tumor-free mice were followed for 40–100 days. The mice were killed if tumors reached 10 mm or became ulcerated, or if the mice showed discomfort. Tumor-free survival was graphed using Kaplan–Meier plots; group survivals were compared using log-rank analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Bartek Jablonski and Diana Sahawneh (both from the Department of Immunology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for their technical help; Stephanie Terzulli (Department of Immunology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for reviewing this manuscript; TC Wu (Department of Pathology, John Hopkins Medical Institutions) for the gift of a plasmid encoding rabbit calreticulin; and Eric Pamer for providing TLR9-deficient mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01CA56821, P01CA33049, and P01CA59350 (to A.N.H.); Swim Across America; the William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Cancer Foundation for Research and the Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (to A.N.H., M.E.E., and J.A.G.-P.). M.E.E. received support from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (fellowship no. 81GE-53218) and the Cancer Research Institute (New York).

REFERENCES

- 1.Butz EA, Bevan MJ. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones SL. Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature. 2001;410:980–987. doi: 10.1038/35073658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B. Tumor antigens recognized by T cells. Immunol Today. 1997;18:267–268. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang R-F, Parkhurst M, Kawakami Y, Robbins P, Rosenberg S. Utilization of an alternative open reading frame of a normal gene in generating a novel human cancer antigen. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1131–1140. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, et al. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Kawakami Y, Loftus D, Appella E, et al. A mutated β-catenin gene encodes a melanoma-specific antigen recognized by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1185–1192. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overwijk WW, Lee DS, Surman DR, Irvine KR, Touloukian CE, Chan CC, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a “self” antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: Requirement for CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2982–2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton AN, Guevara-Patino JA. Immune recognition of self in immunity against cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:468–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI22685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyall R, Bowne WB, Weber LW, LeMaoult J, Szabo P, Moroi Y, et al. Heteroclitic immunization induces tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1553–1561. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelhorn ME, Guevara-Patino JA, Noffz G, Hooper AT, Lou O, Gold JS, et al. Autoimmunity and tumor immunity induced by immune responses to mutations in self. Nat Med. 2006;12:198–206. doi: 10.1038/nm1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guevara-Patino JA, Engelhorn ME, Turk MJ, Liu C, Duan F, Rizzuto G, et al. Optimization of a self antigen for presentation of multiple epitopes in cancer immunity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1382–1390. doi: 10.1172/JCI25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porgador A, Irvine KR, Iwasaki A, Barber BH, Restifo NP, Germain RN. Predominant role for directly transfected dendritic cells in antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells after gene gun immunization. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1075–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timares L, Safer KM, Qu B, Takashima A, Johnston SA. Drug-inducible, dendritic cell-based genetic immunization. J Immunol. 2003;170:5483–5490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Farfan-Arribas DJ, Shen S, Chou TH, Hirsch A, He F, et al. Relative contributions of codon usage, promoter efficiency and leader sequence to the antigen expression and immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:4531–4540. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, Lee D, Corr M, Nguyen MD, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. 1996;273:352–354. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomsen LL, Topley P, Daly MG, Brett SJ, Tite JP. Imiquimod and resiquimod in a mouse model: adjuvants for DNA vaccination by particle-mediated immunotherapeutic delivery. Vaccine. 2004;22:1799–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrone CR, Perales MA, Goldberg SM, Somberg CJ, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Gregor PD, et al. Adjuvanticity of plasmid DNA encoding cytokines fused to immunoglobulin Fc domains. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5511–5519. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goletz TJ, Klimpel KR, Leppla SH, Keith JM, Berzofsky JA. Delivery of antigens to the MHC class I pathway using bacterial toxins. Hum Immunol. 1997;54:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(97)00081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevenson FK, Rice J, Ottensmeier CH, Thirdborough SM, Zhu D. DNA fusion gene vaccines against cancer: from the laboratory to the clinic. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:156–180. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng WF, Hung CF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, et al. Tumor-specific immunity and antiangiogenesis generated by a DNA vaccine encoding calreticulin linked to a tumor antigen. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Hsu KF, Chai CY, He L, Ling M, et al. Cancer immunotherapy using a DNA vaccine encoding the translocation domain of a bacterial toxin linked to a tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3698–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, et al. Improving vaccine potency through intercellular spreading and enhanced MHC class I presentation of antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:5733–5740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, Parkhurst MR, Goletz TJ, Tsung K, et al. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold JS, Ferrone CR, Guevara-Patino JA, Hawkins WG, Dyall R, Engelhorn ME, et al. A single heteroclitic epitope determines cancer immunity after xenogeneic DNA immunization against a tumor differentiation antigen. J Immunol. 2003;170:5188–5194. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allured VS, Collier RJ, Carroll SF, McKay DB. Structure of exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 3.0-Angstrom resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1320–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Liu MA. Presentation of an exogenous antigen by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1590–1596. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spies B, Hochrein H, Vabulas M, Huster K, Busch DH, Schmitz F, et al. Vaccination with plasmid DNA activates dendritic cells via Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) but functions in TLR9-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:5908–5912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rice J, Elliott T, Buchan S, Stevenson FK. DNA fusion vaccine designed to induce cytotoxic T cell responses against defined peptide motifs: implications for cancer vaccines. J Immunol. 2001;167:1558–1565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Duin D, Medzhitov R, Shaw AC. Triggering TLR signaling in vaccination. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savelyeva N, Munday R, Spellerberg MB, Lomonossoff GP, Stevenson FK. Plant viral genes in DNA idiotypic vaccines activate linked CD4+ T-cell mediated immunity against B-cell malignancies. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:760–764. doi: 10.1038/90816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy V, Qiao J, de Campos-Lima P, Caruso M. Direct evidence for the absence of intercellular trafficking of VP22 fused to GFP or to the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase. Gene Ther. 2005;12:169–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundberg M, Johansson M. Is VP22 nuclear homing an artifact? Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:713. doi: 10.1038/90741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Hare P, Elliott G. Reply to “Is VP22 nuclear homing an artifact?”. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:714. doi: 10.1038/90741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins SD, Hartley MG, Lukaszewski RA, Phillpotts RJ, Stevenson FK, Bennett AM. VP22 enhances antibody responses from DNA vaccines but not by intercellular spread. Vaccine. 2005;23:1931–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemken ML, Wolf C, Wybranietz WA, Schmidt U, Smirnow I, Buhring HJ, et al. Evidence for intercellular trafficking of VP22 in living cells. Mol Ther. 2007;15:310–319. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kounnas MZ, Morris RE, Thompson MR, FitzGerald DJ, Strickland DK, Saelinger CB. The α2-macroglobulin receptor/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein binds and internalizes Pseudomonas exotoxin A. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12420–12423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bins AD, Wolkers MC, van den Boom MD, Haanen JB, Schumacher TN. In vivo antigen stability affects DNA vaccine immunogenicity. J Immunol. 2007;179:2126–2133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergman PJ, McKnight J, Novosad A, Charney S, Farrelly J, Craft D, et al. Long-term survival of dogs with advanced malignant melanoma after DNA vaccination with xenogeneic human tyrosinase: a phase I trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1284–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitiello A, Marchesini D, Furze J, Sherman LA, Chesnut RW. Analysis of the HLA-restricted influenza-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in transgenic mice carrying a chimeric human-mouse class I major histocompatibility complex. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1007–1015. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber LW, Bowne WB, Wolchok JD, Srinivasan R, Qin J, Moroi Y, et al. Tumor immunity and autoimmunity induced by immunization with homologous DNA. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1258–1264. doi: 10.1172/JCI4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheibenbogen C, Lee KH, Mayer S, Stevanovic S, Moebius U, Herr W, et al. A sensitive ELISPOT assay for detection of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for HLA class I-binding peptide epitopes derived from influenza proteins in the blood of healthy donors and melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson HA, Barry MA. Maximizing antigen targeting to the proteasome for gene-based vaccines. Mol Ther. 2004;10:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang LE, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn HF. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7987–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harada H, Hiraoka M, Kizaka-Kondoh S. Antitumor effect of TAT-oxygen-dependent degradation-caspase-3 fusion protein specifically stabilized and activated in hypoxic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2013–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeannin P, Renno T, Goetsch L, Miconnet I, Aubry JP, Delneste Y, et al. OmpA targets dendritic cells, induces their maturation and delivers antigen into the MHC class I presentation pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:502–509. doi: 10.1038/82751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao CW, Chen CA, Lee CN, Su YN, Chang MC, Syu MH, et al. Fusion protein vaccine by domains of bacterial exotoxin linked with a tumor antigen generates potent immunologic responses and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9089–9098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hearn AR, De Haan L, Pemberton AJ, Hirst TR, Rivett AJ. Trafficking of exogenous peptides into the proteasome-and TAP-dependent MHC class I pathway following enterotoxin B subunit-mediated delivery. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51315–51322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haynes JR, Arrington J, Dong L, Braun RP, Payne LG. Potent protective cellular immune responses generated by a DNA vaccine encoding HSV-2 ICP27 and the E. coli heat labile enterotoxin. Vaccine. 2006;24:5016–5026. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]