Abstract

Patient: Male, 42

Final Diagnosis: Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP)

Symptoms: Bullous hemorrhagic lesions • elevated liver enzymes

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Rheumatology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) is an IgA small-vessel vasculitis that is primarily a disease of childhood. Its presentation in adulthood is rare and has a more severe disease course. We present a case with an atypical presentation of this disease that was a diagnostic challenge for multiple providers.

Case Report:

A 42-year-old man noticed bullous lesions over his ankles that spread to his entire legs over a few weeks. They later became necrotic and ulcerated areas. His primary care physician and 2 dermatologists could not reach a definitive diagnosis. He then presented to our hospital with new abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and a new elevation in liver enzymes. A biopsy of his skin lesions led to the diagnosis of HSP.

Conclusions:

We discuss this highly unusual initial presentation with bullous skin lesions and liver enzyme abnormalities and explore the medical literature to understand its pathogenesis. Clinicians need to be aware of this rare presentation to avoid a delay in diagnosis and management.

MeSH Keywords: Adult; Blister; Liver Function Tests; Purpura, Schoenlein-Henoch; Skin Diseases, Vesiculobullous; Transaminases

Background

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common vasculitis of childhood but is rare in adults [1]. Adult-onset HSP carries a greater risk of deep organ involvement, especially the renal system, and has a worse outcome [2]. Presence of atypical skin lesions like bullae and necrosis are rare and can be a diagnostic challenge. We discuss a highly unusual presentation of this disease, which caused an initial diagnostic dilemma, and try to understand the pathophysiology of its unique combination of features.

Case Report

A previously healthy 42-year-old Caucasian man had an upper respiratory illness that was conservatively managed. About 10 days later, he noticed painless bullous lesions just above his ankles. These continued to erupt, progressing to the proximal lower extremities, and subsequently converted to tense hemorrhagic bullae (Figure 1). About 3 weeks following the onset, they opened and started draining sero-sanguinous fluid. By now they had developed into painful crusted and ulcerated areas and limited his movement. Concerned, he saw his primary care provider, who was unsure of the diagnosis and referred him to dermatology. Despite being seen by 2 dermatologists, a definitive diagnosis could not be established.

Figure 1.

Tense bullous lesions over bilateral lower extremities (about week 3 of onset of symptoms).

Four weeks into his illness, the patient presented to our Emergency Department with sudden-onset epigastric pain, fever of 101°F, and rectal bleeding. On examination, he was tachycardic and tachypneic, with upper abdominal tenderness and distention. He had extensive ulcerated and necrotic skin lesions, with some areas of palpable purpura now evident over the upper thighs and abdominal wall and over the flexor surface of his forearms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Extensive necrotic skin lesions (on presentation to our hospital Emergency Department). Notice the development of palpable purpura now evident, in addition to the necrotic areas.

Laboratory data revealed a leukocytosis of 22,500 cells/cu mm (N: 4,000–11,000), thrombocytosis of 459,000 cells/cu mm (N: 150,000–450,000), and mild anemia. His ESR was high at 55 mm/hr, and CRP was elevated at 4.2 mg/dL. The liver profile showed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ala-nine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 75, 105, and 161 U/L, respectively. Viral serology, including a hepatitis panel, was negative. The rest of the laboratory data, including prothrombin time, renal function with electrolytes, and a urinalysis with microscopy were within normal limits. Initial autoimmune work-up including antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay and complete anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) panel with c-ANCA, p-ANCA, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and proteinase 3 (PR 3) was negative. An immunoglobulin panel including IgG subtypes was within normal limits, as were serum complement levels including C3 and C4. There were no other concerns or risk factors noted for immunodeficiency. A chest x-ray and abdominal obstruction series showed no acute findings. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for several dilated loops of small bowel with circumferential mural wall thickening, mesenteric edema, and mild ascites (Figure 3). Cultures were obtained and he was admitted for further work-up.

Figure 3.

CT scan of the abdomen showing dilated loops of small bowel with circumferential mural wall thickening (white arrows).

Even though the cause of his ulcerated bullous lesions and abnormal liver profile was not clear, his now-evident purpura, abdominal complaints and other findings were thought suspicious for an atypical presentation of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). A skin biopsy showed intra-epidermal spongiosis with neutrophils, and intra-epidermal small pustules with hemorrhage throughout the papillary dermis. The superficial one-third of the dermis had an intense neutrophilic infiltrate invading most available blood vessels, resulting in fibrinoid degeneration (Figures 4 and 5). Immunofluorescence staining revealed intense granular deposition of C3, and moderate deposition of IgA and IgM in the superficial dermal vessel walls. There was diffuse dermal deposition of fibrin but no deposition of IgG. This confirmed the clinical suspicion of HSP and he also met the ACR and EULAR criteria for the diagnosis.

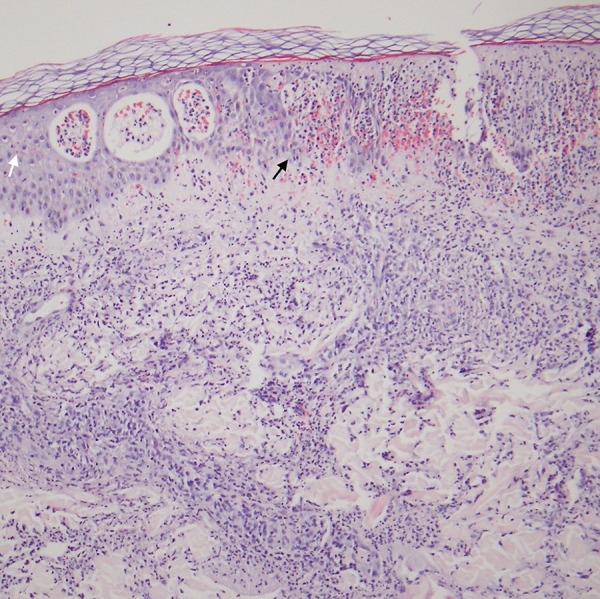

Figure 4.

Skin biopsy (Medium magnification, H&E Staining) Skin biopsy reveals infiltration of the epidermis by neutrophils, causing neutrophilic vesicles and superficial epidermal degeneration (white arrow). The dermis reveals a dense perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils. There is hemorrhage within the epidermis and papillary dermis (black arrow).

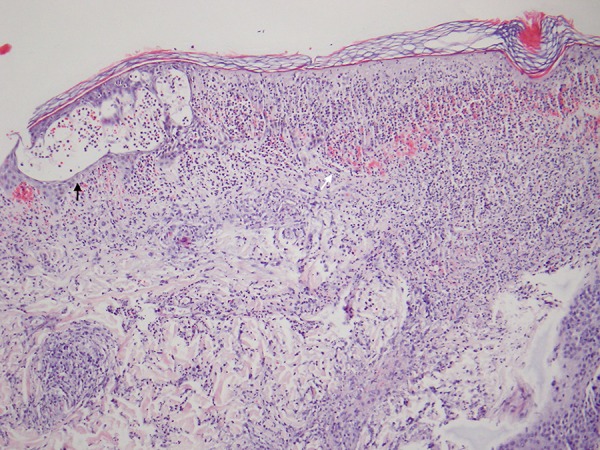

Figure 5.

Skin biopsy (Medium magnification, H & E Staining) Skin biopsy reveals infiltration of the epidermis by neutrophils, causing intra- (black arrow) and subepidermal (white arrow) neutrophilic vesicles and superficial epidermal degeneration. The dermis reveals a dense perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils with mild nuclear dust. There is hemorrhage within the epidermis and papillary dermis.

Given concern of the extent of gastrointestinal involvement and progressive necrotic skin ulcers, he was started on high-dose prednisone at 60 mg a day. He improved and over the next few weeks his leg ulcers healed. His prednisone was tapered and discontinued over the next few months without recurrence. On follow-ups over more than a year, his periodic urinalyses and blood work including liver profile continued to be normal.

Discussion

HSP (also known as Schönlein-Henoch purpura or anaphylactoid purpura) is an IgA-associated small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis [3,4]. Initially described by William Heberden more than 200 years ago, it derives its name from a later description by Johann Lukas Schönlein (1837) and Eduard Heinrich Henoch (1874) [5]. It is largely a disease of childhood, with a peak incidence at around 4–6 years of age [1]. It is, however, rarely reported among adults, in whom the disease is considered to be more severe with relatively poorer prognosis [2].

Classically, HSP presents with a palpable purpura (in the absence of thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy) and variable involvement of the gastrointestinal, articular, and renal systems. Upper respiratory illness precedes the onset of disease in most cases [6]. A skin biopsy may be required for diagnosis, especially in adults due to its low incidence. The presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on light microscopy with IgA immune complex deposition on immunofluorescence is classic and diagnostic of this disease [3,4,6]. Treatment is largely supportive and the role of steroids is controversial [7,8].

Our patient presented with a set of confusing features – bullous and ulcerated lesions – as the initial presenting symptom and elevated liver enzymes including alkaline phosphatase. This unique combination of symptoms requires a better understanding of these unusual manifestations in HSP.

Bullous and necrotic lesions in adult HSP are unusual but the literature is scattered with a highly variable reported incidence. In cases where it is reported, it usually involves co-existing palpable purpura from the onset. Case series by García-Porrúa et al., Blanco et al, and Byun et al. do not address the presence or absence of these lesions at all, highlighting that these manifestations are possibly under-reported [2,9,10]. Bar-On et al. reported a small number of cases (N=21) but specified that none had bullous features [11]. Cream et al. (1970), in a large series on HSP (N=77), reported a 15.6% incidence of bullous lesions and necrosis of the skin [5]. Poterucha et al. also recently reported a case series of 68 patients, with an incidence of vesicular lesions at around 19% [12].

It is very interesting to note that Tancrede-Bohin et al. (N=57) report close to 60% incidence of bullous lesions, which is clearly much higher than that reported by others [13]. Even more interesting is that the reported deep-organ involvement (gastrointestinal 19%, renal 23%, and articular 33%) is the lowest among all reported patient series. Their study excluded patients with HSP who had an underlying autoimmune or inflammatory disorder, or associated malignancies, both of which have an association with adult HSP [14]. Both the absence of these co-existing diseases and the lower rate of deep-organ involvement seem to indicate a better prognosis. This conflicts with a recent report by Belli et al., who in their description of 47 Turkish patients found a significant relationship between frequency of bullous and necrotic lesions and the development of gastrointestinal and renal involvement in HSP [15]. They also note an association with IgM and renal involvement, although Poterucha et al. have previously argued against such a relationship in their cohort [12]. This creates a discrepancy about the relationship between bullous lesions and patient prognosis. Importantly, our patient had obvious bullous lesions and some gastrointestinal symptoms with additional presence of IgM on biopsy, but overall positive outcome and no renal involvement.

There are various hypotheses proposed for the presence of bullous lesions in HSP, mostly from the pediatric literature. These include a pressure hypothesis that describes an increased incidence of bullous lesions in areas of pressure or trauma, especially beneath elastic stockings [16]. There is also a possibility of a pre-existing bullous condition, like dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DDEB) as reported by Abdulla et al. [17]. The immunologic explanations, on the other hand, are based on a few reports in which the bullous fluid itself and/or serum were studied. In 1 study the bullous fluid was compared to serum and found to have a 13-fold higher level of soluble CD25 (sCD 25), suggesting dysregulated humoral immunity [18]. There are also reports of increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the fluid from bullous lesions demonstrated by immunochemistry staining [19]. This is an interesting finding because a recent meta-analysis of pediatric patients with HSP by Zhou et al. found a strong association of nephritis with serum and even urinary levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 [OR=77.21, 95% CI: 54.56–99.86 and p<0.00001] [20]. Our patient had no past history of bullous lesions but he probably did have association with pressure areas because he wore elastic stockings.

Our patient had another interesting feature – elevated liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase. Although this is a unique combination with bullous lesions, there are case reports that mention overlap of HSP with other hepatic diseases. Viola et al. describe a child with HSP and ischemic necrosis of the bile ducts [21]. Although the biopsy did not show positive staining for IgA, the authors thought it was due to a late biopsy, done 44 months after disease onset. Another study describes two cases of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), both of which developed biopsy proven HSP [22]. The authors compared PBC pathogenesis with IgA anti-mitochondrial antibodies to HSP with its IgA predominance. It is interesting to note that other vasculitides, such as Kawasaki disease [23], have been shown to have a plasma cell IgA predominance and cytokine mediators similar to those seen in HSP. Interestingly, none of these reports have mentioned presence of bullous lesions in their case descriptions.

The role of immunosuppression, especially systemic steroids, is controversial in HSP, with arguments both for and against [7,8]. We decided to treat our patient based on abdominal symptoms and extensive necrotic lesions, to aid in early improvement and prevent complications, especially gastrointestinal perforation. The medical literature is clear that renal involvement is not reduced or altered by the use of steroids. The role of corticosteroid use in patients with other manifestations, especially cutaneous bullae or ulcers, remains to be answered.

Conclusions

In summary, our patient had a highly unusual onset of HSP with bullous and necrotic skin manifestations and elevated liver enzymes but good overall outcome without relapse or recurrence over a 1-year follow-up. This unique association requires further attention, and may help better understand the pathogenesis and prognostic features of this disease. Providers in adult medicine need to be aware that HSP can present in unusual forms like in our patient, and early recognition with prompt management where indicated can help prevent morbidity and complications.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Kerith E. Spicknall, MD Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine for providing us images of the patient’s histopathology specimen.

References:

- 1.Gardner-Medwin JMM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, Southwood TR. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360(9341):1197–202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(5):859–64. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1114–21. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, et al. EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cream JJ, Gumpel JM, Peachey RD. Schönlein-Henoch purpura in the adult. A study of 77 adults with anaphylactoid or Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Q J Med. 1970;39(156):461–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(7):697–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Den Boer SL, Pasmans SGMA, Wulffraat NM. Bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein Purpura as indication to start systemic prednisone. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2010;99(5):781–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kausar S, Yalamanchili A. Management of haemorrhagic bullous lesions in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: is there any consensus? J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20(2):88–90. doi: 10.1080/09546630802314670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Porrúa C, Calviño MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32(3):149–56. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.33980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun J-W, Song H-J, Kim L, et al. Predictive factors of relapse in adult with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(2):139–44. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182157f90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bar-On H, Rosenmann E. Schoenlein-Henoch syndrome in adults. A clinical and histological study of renal involvement. Isr J Med Sci. 1972;8(10):1702–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poterucha TJ, Wetter DA, Gibson LE, et al. Histopathology and correlates of systemic disease in adult Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a retrospective study of microscopic and clinical findings in 68 patients at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(3):420–424.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tancrede-Bohin E, Ochonisky S, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Schönlein-Henoch purpura in adult patients. Predictive factors for IgA glomerulonephritis in a retrospective study of 57 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(4):438–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podjasek JO, Wetter DA, Pittelkow MR, Wada DA. Henoch-Schönlein purpura associated with solid-organ malignancies: three case reports and a literature review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(4):388–92. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belli AA, Dervis E. The correlation between cutaneous IgM deposition and renal involvement in adult patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24(1):81–84. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsubara D, Matsubara S. Bullae in pediatric Henoch Schönlein purpura: why some patients develop them? Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(6):680. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdulla F, Sheth AP, Lucky AW. Hemorrhagic, bullous Henoch Schonlein purpura in a 16-year-old girl with previously undiagnosed dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(2):203–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal AS, Dwivedi N, Adsett M. Serum and blister fluid cytokines and complement proteins in a patient with Henoch Schönlein purpura associated with a bullous skin rash. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38(4):190–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SJ, Kim JH, Ha TS, Shin JI. Matrix metalloproteinases and bullae in pediatric Henoch Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(4):483–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou T-B, Yin S-S. Association of matrix metalloproteinase-9 level with the risk of renal involvement for Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Ren Fail. 2013;35(3):425–29. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.757826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viola S, Meyer M, Fabre M, et al. Ischemic necrosis of bile ducts complicating Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):211–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatselis NK, Stefos A, Gioti C, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis and Henoch-Schonlein purpura: report of two cases and review of the literature. Liver Int Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2007;27(2):280–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Recent advances in the understanding and management of kawasaki disease. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(2):96–102. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]