Abstract

Objective

During the transition to young adulthood, youth face challenges that may limit their likelihood of obtaining service use for psychiatric problems. The goal of this analysis is to estimate changes in service use rates and untreated psychiatric cases during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Methods

In a prospective, population-based study, participants were assessed up to 4 times in adolescence (ages 13 to 16; 3983 observations of 1297 participants collected between 1993 and 2000) and 3 times in young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24–26; 3215 observations of 1273 participants collected between 1999 and 2010). Structured diagnostic interviews were used to assess service need (DSM-IV psychiatric status) and behavioral service use in 21 service settings.

Results

During young adulthood, only 28.9% of those meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria also received some treatment in the past 3 months. This compared to 50.9% for the same participants during adolescence. This includes a near-complete drop in use of educational/vocational services as well as declines in use of specialty behavioral services. Young adults most frequently accessed services in either specialty behavioral or general medical settings. Males, African-Americans, those with substance dependence and those living independently were least likely to get treatment. Insurance and poverty status were unrelated to likelihood of service use in young adult psychiatric cases.

Conclusion

Young adults with psychiatric problems are much less likely to receive treatment than when they were adolescents. Public policy needs to address the gap in service use during the transition to adulthood.

Keywords: service use, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, health disparities

Introduction

One espoused goal of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health was to improve access to mental health treatment for all groups (1). To do this, it is necessary to identify groups who fail to use services despite being ill. Children and adolescents with a psychiatric disorder often fail to receive treatment (2–6), or receive inadequate care (6, 7). This concerning level of unmet mental health service need could rise further during the transition to adulthood, which is a developmental period during which vulnerability for several mental health disorders (e.g., substance disorders, panic disorder) is high (8–10), while access to mental health services typically declines. For example, many young adults lose access to services through school (typically a primary portal into mental health services), and many cease to be eligible for health insurance under their parents’ policies (although this may change with recent legislation). Young adults are also less likely to have private insurance than any other age group (11), and many lose eligibility for publicly-funded mental health services when they turn 18 or 21.

To date, information about service use among young adults primarily comes from cross-sectional studies. Analyses combining the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) samples found that 18 to 24 year-olds had the lowest rates of any mental health service use (12). An analysis of the more recent NCS-R alone that also included those ages 25–29, however, failed to find significantly lower rates in any service sector within this age group (13). In NCS-R, 41.4% of adult (ages 18–29) cases received some treatment in the previous 12 months. This compares to a 12-month rate of 45.0% in adolescents (ages 13 to 17) studied in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent (14). A study of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions that focused on the young adult period (ages 19 to 25), however, found fewer than 1 in 4 young adults cases had sought services in the prior year (15). Together, these studies imply a significant drop in service use between adolescence and young adulthood that may recover by the late 20s. None of these samples followed the same group of children through the transition to clarify whether observed differences are due to age (as oppose to cohort or other differences) and to determine why these differences were observed.

Here we use data from a longitudinal community-representative sample in southeastern US that followed children to age 26 with repeated assessments to find out what happens to youths in need of mental health care when they become young adults. The prospective-longitudinal design allows us to look at changes in service use among psychiatric cases as well as changes in predictors of service use. This manuscript will 1) estimate changes in rates of service use from adolescence to young adulthood for psychiatric cases, 2) test associations between service use and sociodemographic (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity, poverty), insurance, and psychiatric variables across this transition, and 3) test how service use is associated with key developmental tasks of the transition to young adulthood (i.e., college, living independently, marriage, and parenthood).

Methods

Sample

A representative sample of three cohorts of children, age 9, 11, and 13 at intake, was recruited from 11 counties in western North Carolina in 1993 (full details (16, 17)). All children scoring above a predetermined cut point on a screener, plus a random sample of the remaining 75% of the total scores, were recruited for detailed interviews. About 8% of the area residents and the sample are African American, 3% are American Indians and less than 1% are Hispanic. Of all participants recruited, 80% (N=1420) agreed to participate. The weighted sample was 49.0% female (N=630). Sampling weights are applied to adjust for differential probability of selection.

Participants were assessed annually to age 16 then again at ages 19, 21 and 24–26. The parent and subject were interviewed by trained interviewers separately until the subject was 16, and participants only thereafter. Before the interviews began, all informants signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This study will focus on two age groups: adolescence (ages 13 to 16; 3983 observations from 1297 participants collected from 1993 to 2000) and young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24–26; 3215 observations from 1273 participants collected from 1999 to 2010). Participation rates were high in both adolescence and young adulthood (>80%). In both age groups, close to 90% of participants completed at least one assessment (adolescence: 91.3%; young adulthood: 89.9%) and attrition was unrelated to psychiatric status at intake (adolescence: p=0.53; young adulthood: p=0.31).

Measures

Psychiatric status

DSM-IV psychiatric disorders were assessed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) 24 until age 16, and the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA),25 the upward extension of the CAPA in young adulthood. The time frame for determining the presence of psychiatric symptoms was the previous three months. In adolescence, symptoms were counted as present if reported by either parent or child or both. In young adulthood, only the participants were assessed. Two-week test-retest reliability of CAPA diagnoses in children aged 10 through 18 is comparable to that of other structured child psychiatric interviews (18, 19). Construct validity including comparison to other interviews is good to excellent (20).

Psychiatric cases in the current analysis include anxiety disorders (panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety, agoraphobia), mood disorders (major depression, dysthymia, mania, and hypomania), behavioral disorders (conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and antisocial personality disorder), and substance dependence. Substance abuse disorders were not included as these disorders require only one symptom and thus criteria are commonly met in young adulthood. The focus on substance dependence is consistent with the more stringent DSM 5.0 standard (21).

Service use was identified using the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) (22). This interview was administered immediately following the CAPA/YAPA and mirrors the 3-month timeframe. As with psychiatric status, service use was coded as positive if either parent or informant reported use up to age 16 and by the subject thereafter. This reflects standard assessment procedures in each age group as well as the primary referral sources. Twenty-one types of service covered in the CASA were categorized into five domains: specialty behavioral (psychiatric hospital, general hospital psychiatry unit, residential treatment facility, community outpatient center, private professional, outpatient drug and alcohol treatment), general medical (hospital medical inpatient, community health center, physician visit, emergency room visit), educational/vocational (boarding school, counselor/social worker, special classes for emotional or behavioral problems, vocational support), informal (religious counselor, crisis hotline, self-help group, friends) and justice system (detention center, probation officer, corrective counsel). To insure that services are mental health/substance related, the CASA is administered immediately after the CAPA/YAPA, it begins by reviewing all identified concerns, and it qualifies all questions about service use with the phrase “for any of the kinds of problems that you told me about”. Service use is coded for mental health/substance treatment only. The CASA also assesses health care coverage. Test-retest reliability of the CASA (self-report interclass correlation coefficient =0.74; parent-report =0.76) and concurrent validity with official mental health/substance center records was good (23, 24).

Predictors of service use and young adult milestones

Sociodemographic variables included sex, age period (adolescence or young adulthood), race-ethnicity (White, American Indian, African-American), and poverty status based upon the federal definition (25). Participants were asked about educational attainment, marital status, living situation, and parenthood to address young adult milestones. All variables were assessed using the CAPA/YAPA and CASA interviews.

Analytic framework

Sampling weights were applied in all analyses to insure that results represent unbiased estimates for the original sample population. In addition, sandwich type variance corrections (26) were applied to adjust the standard errors for the sampling stratification and repeated assessments of the same participants over time. Weighted logistic regression analyses were used to study the effect of age period, demographic factors, insurance status, diagnostic status, and young adult milestones on service use. All models were implemented in SAS PROC GENMOD using the REPEATED statement (27).

Results

Rates of 3-month service use

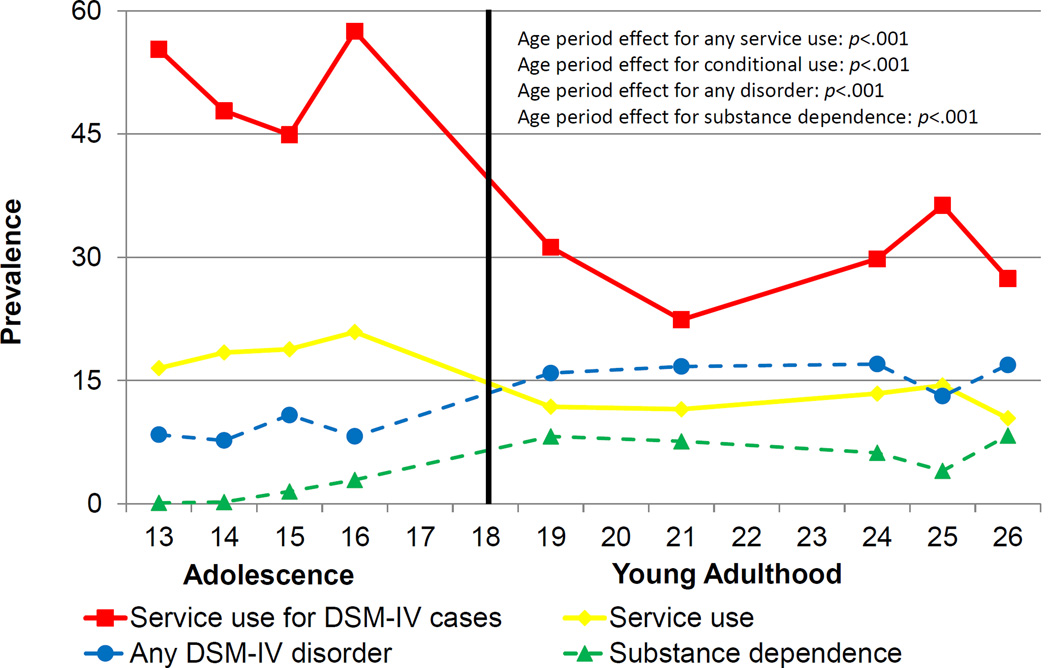

The 3-month rates of psychiatric disorders increased from adolescence (ages 13 to 16) to young adulthood (ages 19, 21, and 24–26; 8.9% to 15.9%, p <.001), whereas the rate of service use for those cases – hereon referred to as conditional service use - declined steeply (50.9% of cases to 28.9% of cases, p<.001; see figure 1). A portion of the increase in the 3-month rates of psychiatric cases is accounted for by substance dependence (1.3% in adolescence vs. 7.3% in young adulthood, p<.001).

Figure 1.

3-month prevalence rates for having a DSM-IV disorder from ages 13 to 26, a substance disorder, and service use for psychiatric cases. Rates conditional on diagnosis are limited to individuals meeting full diagnostic criteria for DSM disorders at same assessment as service use evaluation.

The observed decline in conditional service use could be an artifact of shifting from two informants in adolescence (parent and self-report) to a single informant in young adulthood (self-report). Conditional service use rates were lower in adolescence when relying upon self-report data only, but these rates were still significantly higher than young adult rates (38.3% to 28.9%, p<.002). Furthermore, rates of psychiatric disorders rose significantly from adolescence to young adulthood despite the shift to a single informant. Thus, the loss in parents as informants during young adulthood did not account for the significant declines in conditional service use.

Table 1 shows the downward shift in service use from adolescence to young adulthood across service sectors. Use of educational/vocational services became rare among all groups. Among psychiatric cases, there were also significant declines in the use of specialty behavioral and informal services. Given the increases in rates of substance dependence in young adulthood, it is reasonable to suggest that the lower conditional service use rates were genuinely related to lower service use by young adults with substance disorders. Service rates were generally higher for non-substance psychiatric cases as compared to psychiatric cases overall, but even non-substance psychiatric cases displayed significantly lower rates of overall service use, educational/vocational services, and informal services in young adulthood and somewhat lower rates of specialty behavioral compared to the adolescent group.

Table 1.

Overall 3-month rates of service use in different service sectors in adolescence and young adulthood and rates for psychiatric cases and nonsubstance psychiatric cases.

| Overall sample | Any psychiatric case (i.e., “conditional service use”) |

Any MH case (no substance) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13–16 | 19–26 | Diff? | 13–16 | 19–26 | Diff? | 13–16 | 19–26 | Diff? | |||||||

| % | SE | % | SE | P | % | SE | % | SE | p | % | SE | % | SE | p | |

| Any service | 18.7 | .01 | 12.2 | .01 | <.001 | 50.9 | .04 | 28.9 | .03 | <.001 | 52.2 | .04 | 35.3 | .04 | .01 |

| Specialty behavioral | 6.9 | .01 | 4.8 | .01 | .06 | 22.8 | .03 | 11.6 | .02 | .005 | 22.9 | .03 | 15.9 | .03 | .12 |

| General Medical | 2.9 | .01 | 2.7 | .01 | .81 | 12.6 | .03 | 9.8 | .02 | .47 | 12.1 | .03 | 12.6 | .03 | .87 |

| Education* | 6.9 | .01 | 0.3 | .01 | <.001 | 17.3 | .03 | 0.3 | .01 | <.001 | 17.8 | .03 | .4 | .01 | <.001 |

| Informal | 6.9 | .01 | 4.1 | .01 | .003 | 20.0 | .03 | 9.1 | .02 | .002 | 20.9 | .03 | 11.1 | .03 | .01 |

| Justice system | 2.7 | .01 | 2.5 | .01 | .89 | 8.3 | .02 | 6.6 | .01 | .71 | 8.4 | .02 | 6.5 | .02 | .59 |

Includes vocational services in adulthood. Difference test compares adolescence to young adult adulthood. All percentages are weighted.

Sociodemographic, Insurance and Diagnostic predictors of service use

Table 2 shows demographic, insurance and diagnostic status covariates of service use for psychiatric cases during adolescence and young adulthood. An interaction term with the age-group variable tested whether these associations changed significantly from adolescence to young adulthood (indicated by an asterisk in table 2). Education/vocational services were excluded because of their low rates in adulthood. Results for justice system services are similar to correlates for justice system involvement (available upon request from first author).

Table 2.

Associations between adolescent and young adult service use and demographics, insurance status and diagnostic status in mental health cases.

| Any Service Use | Specialty Behavioral | General medical | Informal | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13–16 | 19–26 | INT | 13–16 | 19–26 | INT | 13–16 | 19–26 | INT | 13–16 | 19–26 | INT | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

p | OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

p | OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

p | OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

p | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Female | 1.3 | .7–2.5 | 1.3 | .7–2.5 | 1.4 | .7–2.9 | 3.2 | 1.2–8.1 | * | 3.2 | 1.2–9.2 | 1.3 | .5–3.4 | 1.1 | .5–2.5 | 3.3 | 1.3–8.5 | * | ||

| Race | ||||||||||||||||||||

| White | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Indian | 1.5 | .9–2.5 | 1.3 | .8–2.2 | 1.1 | .6–2.1 | 1.0 | .5–2.2 | .7 | .3–1.7 | 1.8 | .9–3.7 | 1.1 | .6–2.1 | .6 | .2–1.7 | ||||

| Black | 2.1 | .6–7.5 | .3 | .1–.7 | ** | 1.1 | .4–3.2 | .1 | .0–.7 | ** | .2 | .0–.9 | .2 | .0–.8 | .5 | .2–1.7 | .2 | .0–0.8 | ||

| Poverty | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Yes | 1.1 | .5–2.3 | 1.1 | .6–2.3 | 1.2 | .5–2.6 | .9 | .4–2.4 | .7 | .3–2.0 | .7 | .2–2.2 | 1.3 | .5–3.2 | 0.7 | .3–1.8 | ||||

| Insurance | ||||||||||||||||||||

| None | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Private | 1.0 | .4–2.2 | 1.8 | .9–3.8 | 2.3 | .5–9.7 | 1.3 | .5–3.3 | 2.7 | .5–13.4 | 1.2 | .3–4.4 | .4 | .2–1.0 | 1.9 | .7–5.5 | ** | |||

| Public | 1.6 | .6–4.4 | 1.8 | .8–4.1 | 5.4 | 1.2–24.0 | 2.3 | .8–6.8 | * | 2.3 | .3–20.4 | 1.5 | .5–4.9 | .5 | .2–1.2 | .8 | .2–2.3 | |||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other dx | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Depression | 1.4 | .7–2.7 | 0.7 | .4–1.2 | 2.1 | 1.0–4.5 | .5 | .2–1.2 | * | 2.7 | .9–8.1 | .9 | .3–2.3 | * | 1.1 | .5–2.4 | .7 | .3–1.7 | ||

| Anxiety | .8 | .3–1.7 | 1.7 | 1.0–3.2 | .5 | .3–1.0 | 2.3 | 1.0–5.5 | * | 1.1 | .3–3.8 | 2.7 | 1.1–6.8 | 1.1 | .5–2.4 | 2.2 | 0.8–6.0 | |||

| Substance | 1.8 | .7–4.7 | .5 | .3–.9 | * | 2.0 | .7–5.9 | .3 | .1–.8 | * | 1.4 | .4–5.5 | .4 | .2–1.2 | * | 0.8 | .3–2.2 | .6 | .2–1.6 | |

| Behavioral | 1.5 | .8–2.9 | 1.1 | .5–2.4 | 1.2 | .6–2.5 | .5 | .2–1.5 | .8 | .3–2.3 | .2 | .0–0.8 | 1.3 | .7–2.6 | .2 | .1–.7 | * | |||

INT refers to statistical interactions of predictor with developmental period. Under diagnosis, other dx refers to all disorders other than that being tested. Thus, depression status was compared to all other nondepression psychiatric cases.

A * indicates interaction is significant at p<.05.

A double check mark indicates interaction is significant at p<0.001.

Sociodemographic

As compared to adolescents, young adult females cases were more likely than males to report specialty behavioral and informal service use. Young adult African American cases generally had lower rates of service use as compared to whites. In the case of specialty serivces, this was a significant drop from the pattern in adolescence where rates were similar. Poverty status was not associated with service use in either age group.

Insurance

In adolescence, 75.5% of participants had some form of private insurance, 14.7% had public insurance only, and 9.8% were uninsured. These rates shifted in young adulthood to 68.4%, 10.3%, and 21.3%, respectively. The likelihood of being uninsured peaked at ages 19 and 21 (27.0%) but dropped to adolescent levels by the mid-20s (10.5%). This shift was limited to young adult whites and African Americans; very few young adult American Indians were uninsured (3.5%). Nevertheless, these shifts in insurance status had little effect on service use in young adulthood.

Diagnosis

Type of diagnosis affected service use in all young adult sectors: Anxiety was associated with higher levels of insurance-based services and general medical services, whereas having a substance disorder was associated with lower levels of specialty services and showed a similar trend in other sectors. Both of these patterns were relative shifts from adolescence. Young adult participants with depression had significantly lower levels of insurance–based service than was seen in adolescence.

Young adult milestones and service use

Young adulthood commonly involves moving out of one’s parent’s home, going to college and, in some cases, getting married and/or having children. Most youths (74.1%) lived with a parent at age 19, this rate dropped to 17.9% by the mid-20s. Rates of some post-secondary education increased from 50.9% at age 19 to 66.7% by the mid-20s. Marriage and parenthood were less common, beginning at 5.9% and 11.2% at age 19 and increasing to 43.2% and 37.6% by the mid-20s, respectively. None of these milestones significantly predicted psychiatric status in young adulthood (results available from first author), however, living away from the parental home was associated with lower levels of any service use, and especially insurance based services – both specialty behavioral and general medical (any service use: OR=.4, 95%CI =.2-.8; specialty MH: OR =.4, 95%CI =.2–1.0; general medical: OR =.4, 95%CI =.2-.8; informal: OR =1.2, 95%CI =.5–3.4).

Discussion

Neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disease burden in youths ages 10 to 24 (28). During this period, youths are faced with a series of educational, family, and social transitions. In this sample, the rates of untreated psychiatric cases almost doubled from adolescence to young adulthood: Less than one in three young adults who met criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis reported use of services in any sector. Part of this drop was accounted for by loss of secondary education services, but young adult psychiatric cases also were less likely to use specialty behavioral and informal services. Increased rates of substance dependence coupled with decreased service use put young adults at high risk for unmet psychiatric need.

This sample comes from a relatively rural area in the southeastern United States, and, while the sample is representative of that area, African Americans and Latinos are underrepresented and American Indians are overrepresented as compared to the US population. This raises the question of how informative this sample is about patterns and predictors of conditional service use. Rates of psychiatric illness in this sample are very similar to those found in other national and international population samples (29, 30) and the proportion of children receiving needed mental health/substance care is similar to other areas of the US (3, 6, 31–33). Our adolescent conditional 3-month service use rate of 49.3% compares to a 45.0% 12-month rate in NCS-A (14), and our young adult 3-month rate of 24.6% compares to “fewer than 25% of individuals with a mental disorder in the prior year” in NESARC (p. 1429) (15). Our service use rates are very similar to those rates from nationally-representative cross-sectional surveys. Service use was not assessed with administrative records, because many affected individuals never access any services and not all mental health/substance services are recorded in accessible databases. However, self and parent-reported service use converge with data from institutional records (23, 34, 35).

The 3-month service use rate for young adult cases of 28.9% is much lower than the 50.9% reported for adolescent cases, and also than reports from prior cross-sectional studies (13, 36). Young adulthood seems to be a distinctive period for unmet need as compared to adolescence and also later adulthood (41.1% in NCS-R adult cases (13)). One obvious reason is that public, tuition-free schooling ends in late adolescence, taking away youths’ primary entry point to the mental health/substance service system (7). College-based services failed to fill this gap in the current study. College students may not always be aware of the services available to them. Surveys of active college students that students at private colleges with lower enrollments have higher service use rates (37), but the majority of young adults is not enrolled in such colleges. Young adults also failed to access either insurance- and noninsurance-based services. This implicates referral behavior as a reason for unmet service need. Adolescents are typically referred for services by parents (7), but for many young adults, particularly those living independently, service use is dependent on self-referral. This raises questions about the young adult’s beliefs about service need, stigma or effectiveness, as well as motivation in the face of other distractions and symptoms of their illness. Finally, the rise of substance disorders during young adulthood may lead youths misusing substances to believe that their dependence behavior is normative and reducing the perceived need for help. Alternatively, it could be that fewer services are available for substance problems as compared to general mental health issues.

Some young adult cases did receive services. The likelihood of receiving those services was not related to either insurance status or poverty – two oft-noted assumed barriers to receipt of services. Young adults who received either specialty behavioral or general medical services tended to be white and American Indian youths living at home and/or dealing with anxiety. Living with one’s parents in young adulthood is a trend that is on the rise in US (38) and abroad (39). This trend has been bemoaned in the popular press (40, 41) with such children described as “boomerang kids.” Our study did not look at aspects of this arrangement that may be problematic, but young adults coping with mental illness and living at home were advantaged as compared to those either living independently or with a romantic partner or spouse.

Race/ethnicity disparities in services use are common (13, 36) but the lower rates of specialty behavioral and informal services for African American young adults were a sharp departure from their pattern in adolescence. These disparities were not accounted for by poverty, insurance status or living situation. Young adulthood should be a priority period of study to understand barriers to use in African American youths.

Conclusion

This study paints a dire picture of service use during the transition to adulthood. Mental health/substance service use should be contingent on need - not age, race or living situation. Institutional barriers such as the discontinuity of education-based services, lack of continuity between childhood and adult service systems, and loss of insurance for many young adults need to be addressed (42, 43). This study suggests, however, that even if these barriers were addressed, untreated cases would persist. Young adults failed to use services that were not contingent on insurance status, infrastructure, or funding. Only young adults still living with a parent showed levels of specialty and general medical services similar to those observed in adolescence. This suggests that policy efforts must focus as much on young adults’ beliefs and knowledge about mental illness and service use as they do on insuring broad access to care.

Acknowledgements

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH63970, MH63671, MH48085), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301, DA036523), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (Early Career Award to First Author), and the William T Grant Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

None of the authors have biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

William E Copeland, Duke University - Department of Psychiatry, Box 3454 DUMC 905 W Main St, Ste 22, Durham, North Carolina 27701, william.copeland@duke.edu.

Lilly Shanahan, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Maryann Davis, University of Massachusetts Medical School - Center for Mental Health Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, 55 Lake Ave. N., Worcester, Massachusetts 01655.

Barbara Burns, Duke University - Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Durham, North Carolina.

Adrian Angold, Duke University - Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Brightleaf SQ Ste 22B 905 W Main St, Durham, North Carolina 27701.

E. Jane Costello, Duke University - Psychiatry, Suite 22 905 West Main St., Durham, North Carolina 27701.

References

- 1.President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/reports.htm2004.

- 2.Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer E, Fairbank J, Burns B, Keeler G, et al. Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and White youth. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:893–901. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA, Horwitz SM. Patterns of mental health utilization and costs among children in a privately insured population. Health Services Research. 2001;36(1 Pt 1):113–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, Tweed D, Stangl D, Farmer EMZ, et al. Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995;14:147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwitz SM, Gary LC, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. Do needs drive services use in young children? Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1373–1378. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leaf PJ, Alegria M, Cohen P, Goodman SH, Horwitz SM, Hoven CW, et al. Mental health service use in the community and schools: Results from the four-community MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):889–897. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farmer E, Burns B, Phillips S, Angold A, Costello E. Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(1):60–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton W, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of dsm-iv drug abuse and dependence in the united states: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Longitudinal Patterns of Anxiety From Childhood to Adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills RJ, Bhandari S. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2002: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells K, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the united states. Archive of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costello EJ, He J-p, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Services for Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders: 12-Month Data From the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent. Psychiatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100518. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S-M, et al. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns B, Stangl D, Tweed D, Erkanli A, et al. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, designs, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Longitudinal Patterns of Anxiety From Childhood to Adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angold A, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Goodman R, Fisher PW, Costello EJ. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interviews for Children and Adolescents: A Comparative Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fifth edition (DSM-5) Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ascher BH, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Angold A. The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): Description and psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1996;4:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ascher BH, Z Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Angold A. The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): Description and Psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1996;4(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farmer EMZ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Costello EJ. Reliability of self-reported service use: Test-retest consistency of children's responses to the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1994;3(3):307–325. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalaker J, Naifah M. Poverty in the United States: 1997. US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports: Consumer Income. 1993:60–201. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pickles A, Dunn G, Vazquez-Barquero J. Screening for stratification in two-phase ('two-stage') epidemiological surveys. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1995;4(1):73–89. doi: 10.1177/096228029500400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® Software: Version 9. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harhay MO, King CH. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years. The Lancet. 2012;379(9810):27–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts R, Attkisson C, Rosenblatt A. Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:715–725. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffee S, Harrington H, Cohen P, Moffitt TE. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorder in youth. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(5):406–407. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000155317.38265.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Leventhal JM, Forsyth B, Speechley KN. Identification and management of psychosocial and developmental problems in community-based, primary care pediatric practices. Pediatrics. 1992;89(3):480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staghezza-Jaramillo B, Bird HR, Gould MS, Canino G. Mental health service utilization among Puerto Rican children ages 4 through 16. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1995;4(4):399–418. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, Rae-Grant NI, Links PS, Cadman DT, et al. Ontario child health study: II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:832–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210084013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Henly GA, Schwartz RH. Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. International Journal of the Addictions. 1991;11A:1379–1395. doi: 10.3109/10826089009068469. 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrington DP. Pinard G-F, Pagani L, editors. Predicting adult official and self-reported violence. Clinical assessment of dangerousness: Empirical contributions. 2001:66–88. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Service Utilization for Lifetime Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N, Zivin K. Mental health service utilization among college students in the United States. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199(5):301–308. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182175123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian Z. During the Great Recession, More Young Adults Lived with Parents. Providence, RI: US2010 Project; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone J, Berrington A, Falkingham J. The changing determinants of UK young adults' living arrangements. Demographic Research. 2011;25(20):629–666. [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Arcy J. More adult kids living with parents and in no rush to depart. Washington Post. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gregoire C. Adult Children Living At Home? 5 Ways To Create A Less Stressful Existence With Your Boomerang Kids. Huffington Post. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis M. Addressing the needs of youth in transition to adulthood. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2003;30(6):495–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1025027117827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner M, Davis M. How are we preparing students with emotional disturbances for the transition to young adulthood? Findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study—2. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2006;14(2):86–98. [Google Scholar]