Abstract

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a self-limited benign epithelial proliferative lesion that eventually presents with very similar clinical features to squamous cell carcinoma. Many KA appear in the vermilion border of the lips and therefore dental professionals must be familiar of the disease. This article reports the case of a 40-year-old female patient presenting with an exophytic ulcerative tumor in her lower lip that resolved after incisional biopsy. Photographic documentation of the case is presented and topics that are relevant to the clinical management of the disease are addressed.

Keywords: keratoacanthoma, Regression after biopsy, Lip cancer

INTRODUCTION

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a benign epithelial proliferative lesion that commonly affects the vermillion border of the lips7.The disease usually represents a diagnostic challenge for the clinician since both clinical and histopathologic features of KA may resemble those of a well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)8,9. Notwithstanding this alarming presentation, the hallmark of the disease is spontaneous resolution after an intermediary stationary stage8,9. In this sense, observational and experimental data about the biological behavior of KA have suggested that the outer root sheath of the hair follicle infundibulum is the origin of these lesions, since pillous follicles naturally evolve through cycles comprising phases of activity/growth (anagen), transition (catagen) and resting/loss (telogen)3,9. Immunohistochemical studies corroborated similarities between KA and the outer root sheath beneath the infundibulum5. Furthermore, the disease is also much more frequent in hair-bearing skin9. Finally, KA may be multiple, disseminated and associated with syndromic diseases (e.g. Muyr-Torre, xeroderma pigmentosum), probably due to autossomal defective DNA-repair mechanisms2,9. Almost all KA cases are treated by surgical excision. For this reason, very few cases have been documented until resolution, which constitutes the "goldstandard" for this diagnosis1,11. This article presents a photographic documentation of a KA in the lower lip of a 40-year-old female. The initial presentation was suggestive of SCC and the patient was submitted to an incisional biopsy. After an inconclusive pathological impression, the patient was reevaluated and incidental partial regression was noticed. The diagnosis was then revised to KA. Complete resolution was achieved within two months without significant scarring. A discussion on the diagnostic and therapeutic management of lesions suspected as being KA is presented.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old female was referred to the Oral Diagnosis service of our institution with a 7-month complaint of lower lip ulceration. There was no description of previous local trauma, but the patient reported continuous out-door working without sunscreen protection, as well as 20 years of smoking. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

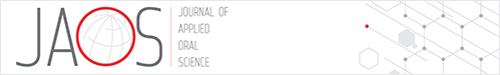

Facial examination revealed a 1.5-cm nodule on the left side of the vermillion border of lower lip. It was asymptomatic, sessile, flat and well-defined. Its surface was erythematous and ulcerated, partially recovered by a brown and adherent crust (Fig 1). The margins of the lesion were indurated and apparently infiltrative. There was no other alteration in the face or neck. The patient did not mention any other lesion throughout her body. Intraoral examination was also non-contributory.

FIGURE 1. Initial aspect of the patient, showing a nodular exophytic lesion in the inferior lip, with superficial ulceration and partial brown-pigmented crust covering.

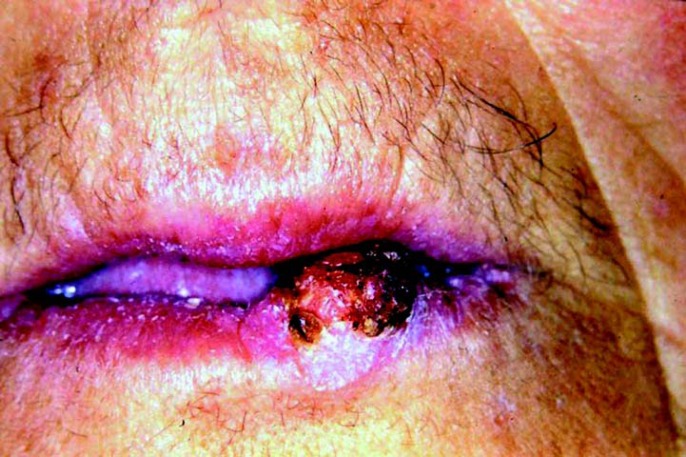

An incisional biopsy was performed to rule out the possibility of squamous cell carcinoma. The histopathologic examination revealed an epithelial proliferation with elongated rete ridges, some presenting a droplet shape, hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, basal cell nuclear hyperchromatism, conspicuous nucleoli, increased mitotic activity with normal morphology, and focal loss of basal membrane. Epithelial islands were intermingled with the underlying connective tissue and were accompanied by mild inflammatory infiltrate, reminding a pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Fig 2). Basophilic change was also identified in the lamina propria. PAS and Grocott's silver methenamine stains were performed but did not reveal infectious agent. The pathological findings were considered compatible, but highly inconclusive with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and another biopsy was suggested by the surgical pathology staff.

FIGURE 2. Representative aspects of the histological features observed in the initial biopsy. A Low-power view of the tissue section presenting epithelial proliferation and apparent invasion of the lamina propria in one of the fragment borders (arrow). [Hematoxylin-eosin stain, scale-bar = 1mm] B Detail of epithelial projections observed in the specimen presenting acanthosis (white bar), abrupt keratin pearl formation (black arrow), mild cellular pleomorphism in the basal layer (black star), occasional mitosis (white arrow), and moderate infiltrate by inflammatory cells (white star). [Hematoxylin-eosin stain, scale-bar = 125 μm].

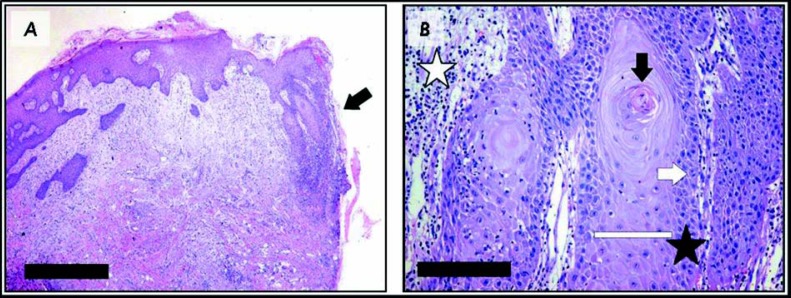

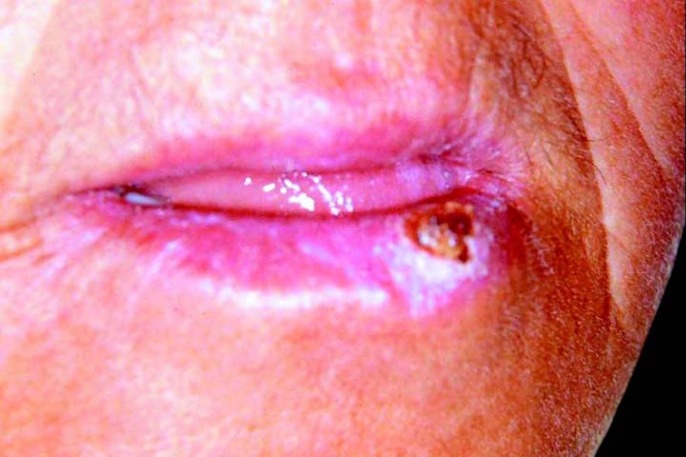

The patient returned 7 days after the initial biopsy with mild regression of the tumor (Fig 3), which is a completely unexpected finding for a true malignant neoplasm. Association of this observation with the initial clinical aspect of the lesion as well as its histopathological presentation raised the hypothesis of keratoacanthoma. The patient was informed about this possibility, but refused further surgical treatment. It was then proposed clinical follow-up at every two weeks associated to hat and sunscreen use. The lesion completely disappeared after two months without significant scarring (Fig 4). There was not recurrence throughout two years of follow up.

FIGURE 3. Clinical aspect of the lesion after the initial surgical intervention (biopsy), demonstrating partial regression compared to Figure 1 .

FIGURE 4. Final aspect of the patient, two months after the second biopsy, showing complete involution of the lesion without significant scarring.

DISCUSSION

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are common in pale-complexioned populations that are chronically exposed to sun radiation, such as in Australia and Brazil9,10. It is frequent on the face, especially in the lower lip, and therefore dentists should be alert for this disease4,8. In general, KAs are solitary tumors depicting a central keratin plug. It is usually present for some months before the initial appointment, and a history of rapid growth followed by a stationary period and then sometimes by partial regression is eventually reported8,9. However, as in the present case, some KAs do not completely fit to this pattern. Our patient did not recall stationary or regressive behavior, clinical aspect was more suggestive of a true neoplastic alteration, and involution was only observed after surgical intervention. In this sense, KA must be included in the diagnostic hypothesis list for every nodular-ulcerative conditions of the lower lip, even though such alterations more likely resemble solitary manifestation of specific bacterial and mycotic infections, actinic cheilosis, and even SCC.

Cases suspected for KA must be carefully conducted. Griffiths4 proposed principles for "watch and wait" management. It should include initial identification that the lesion had been larger, had reached its growth plateau phase or even is actually regressing, with no biopsy in case of high suspicion, close follow-up every 2 weeks, and photographic documentation at each visit. However, any lesion in immunocompromised individuals must be immediately excised. Furthermore, suspected solitaries cases that fail to respond within 4 to 6 weeks demands obligatory surgical excision. We completely agree with these propositions, but this protocol is not always straightforward, as occurred in the present case. In this sense, only those cases with clear identification of static or regression phases should be closely accompanied. As in the present case, noticeable involution after surgical intervention should also be regarded as indicative of KA. On the other hand, lesions that are clinically or even histopathologically identified as possible KA but that are examined on its growth stage should be better treated aggressively since it is very difficult at this moment, if not impossible, to reach an absolute distinction of this lesion from a SCC or other aggressive entity.

Microscopic diagnosis of KA requires complete excision or at least a partial biopsy that includes the center and both margins of the lesion, which are essential to evidence sharp demarcation between tumor and stroma, cup-shaped appearance and a deep but distinct collar-like invasive front of the epithelium1,6,7,8. Abundant and atypical mitosis, as well as pleomorphism must favor SCC 4. Immunohistochemistry can be performed to aid in differentiation between KA and SCC 1,9

Whether spontaneous or stimulated by prior surgical manipulation, regression has been highlighted as the only definitive evidence for KA, but only few photographic-proven series are available in the English literature4,6,11. In this sense, most of the KA is completely excised because pathological and esthetically unpleasant scarring may develop in the lesion site after involution6. It was not observed in the present case. There are other reports demonstrating none to only acceptable scar after resolution4. Finally, initial presentation of KA may be worrisome, but there are indications that patients usually tolerate well follow-up as they see the lesion getting smaller4. Observation procedure is not necessarily associated with increased rates of recurrences, but evidence for this is still scarce6.

CONCLUSION

The herein documented complete regression of KA was probably influenced by inflammatory changes occurred after biopsy. Since it may be very difficult to distinguish KA from other aggressive pathological entities, it should be better managed by complete resection. Only cases presenting indisputable regression should be carefully followed-up until complete disappearance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cribier B, Asch P, Grosshans E. Differentiating squamous cell carcinoma from keratoacanthoma using histopathological criteria. Is it possible? A study of 296 cases. Dermatology. 1999;199:208–212. doi: 10.1159/000018276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiorentino DF, Nguyen JG, Egbert BM, Swetter SM. Muir-Torre syndrome: confirmation of diagnosis by immunohistochemical analysis of cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:476–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.07.027. [letter] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghadially FN. The role of the hair follicle in the origin and evolution of some cutaneous neoplasms of man and experimental animals. Cancer. 1961;14:801–816. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(199007/08)14:4<801::aid-cncr2820140417>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:485–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichikawa E, Ohnishi T, Watanabe S. Expression of keratin and involucrin in keratoacanthoma: an immunohistochemical aid to diagnosis [letter] J Dermatol Sci. 2004;34:115–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBoit PE. Can we understand keratoacanthoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:166–168. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löning T, Jäkel KT. World Health Classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Keratoacanthoma. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;30:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma: a clinico-pathologic enigma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:327–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan JJ. Keratoacanthoma: the Australian experience. Aust J Dermatol. 1997;38:S36–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visscher JGAM, van der Wal JE, Starink TM, Tiwari RM, van der Wal I. Giant keratoacanthoma of the lip: report of a case of spontaneous resolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]