Abstract

Objective To determine the time to benefit of using flexible sigmoidoscopy for colorectal cancer screening.

Design Survival meta-analysis.

Data sources A Cochrane Collaboration systematic review published in 2013, Medline, and Cochrane Library databases.

Eligibility criteria Randomized controlled trials comparing screening flexible sigmoidoscopy with no screening. Trials with fewer than 100 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings were excluded.

Results Four studies were eligible (total n=459 814). They were similar for patients’ age (50-74 years), length of follow-up (11.2-11.9 years), and relative risk for colorectal cancer related mortality (0.69-0.78 with flexible sigmoidoscopy screening). For every 1000 people screened at five and 10 years, 0.3 and 1.2 colorectal cancer related deaths, respectively, were prevented. It took 4.3 years (95% confidence interval 2.8 to 5.8) to observe an absolute risk reduction of 0.0002 (one colorectal cancer related death prevented for every 5000 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings). It took 9.4 years (7.6 to 11.3) to observe an absolute risk reduction of 0.001 (one colorectal cancer related death prevented for every 1000 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings).

Conclusion Our findings suggest that screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is most appropriate for older adults with a life expectancy greater than approximately 10 years.

Introduction

Screening with fecal occult blood testing or flexible sigmoidoscopy has been shown to decrease colorectal cancer related mortality but can also lead to harms.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 These harms include pain, worry, colonic perforation, and cardiac, renal, or cognitive complications from fluid shifts during bowel preparation.8 9 Though the benefits of screening are not seen for many years, the harms are seen immediately.10 Since patients with limited life expectancy are exposed to the immediate harms of screening with little chance that they would see benefit, guidelines now recommend that screenings should be targeted toward patients whose life expectancy exceeds the time to benefit from colorectal cancer screening.11

Though colonoscopy is widely used as a screening method for colorectal cancer, the evidence of benefit is stronger for flexible sigmoidoscopy. Four large, randomized controlled trials have shown that screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy reduces colorectal cancer related mortality.12 13 14 15 While ongoing screening colonoscopy trials may show that the procedure provides additional benefit when results are reported in 7-12 years, they may also show that for the average patient at risk, the benefit of visualizing the proximal colon is outweighed by the higher risks associated with colonoscopy.16 17 18 The evidence of benefit from screening flexible sigmoidoscopy led the UK Department of Health in 2011 to invest £60m ($89m; €82m) to “incorporate flexible sigmoidoscopy into the current bowel screening programme,” with a goal of 100% coverage by 2016, making screening flexible sigmoidoscopy a timely and relevant topic for many clinicians.19

To appropriately target screening flexible sigmoidoscopy to patients most likely to benefit, both life expectancy and time to benefit for such screening must be determined. Recent studies have identified numerous mortality indices to determine life expectancy and many of these indices are available online at www.eprognosis.com.20 21 Though the time to benefit for screening using a fecal occult blood testing has been estimated to be 10.3 years to prevent one colorectal cancer related death for every 1000 people screened, the time to benefit for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is unclear.22

We carried out a survival meta-analysis of the major randomized controlled trials for colorectal cancer screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy to determine its time to benefit, defined as the time to reduction in colorectal cancer related mortality after screening.

Methods

Data sources

We focused on randomized controlled trials comparing screening flexible sigmoidoscopy with no screening identified by the 2013 Cochrane Collaboration systematic review entitled “Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals.”23 On 11 October 2014 we carried out a search using the strategies outlined in that review15 (see appendices 1 and 2 on bmj.com). We excluded trials with fewer than 100 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings (Telemark Polyp Study I).6

Data extraction

To combine data from individual studies into a summary pooled lag time to benefit, we determined the absolute risk reduction at each year after screening. To determine the annual absolute risk reduction, we sought the annual number of colorectal cancer related deaths and the annual number of participants at risk for each arm (invited to screening versus control) for each study. The US, Norway, and UK trials provided this information through mortality curves.12 13 14 15 Since the US study provided biennial mortality and number at risk data, we used linear interpolation to estimate mortality and number at risk data for every other year. An Italian study provided this information through email correspondence.15 To determine the annual rate of cancer mortality, we followed the Messori procedure, scanning survival curves and analyzing the scanned images to determine quantitative estimates of number of people at risk, number who died, and number who were censored in each year.24 This method has been shown to accurately reproduce summary survival curves without the need for individual patient data.25

Statistical analysis

To estimate a pooled time to benefit, we combined survival data from all four studies to obtain pooled annual risk reduction estimates, allowing the time to specific absolute risk reduction thresholds to be determined. Unlike most meta-analyses where the main statistic of interest (for example, hazard ratio with confidence intervals) is reported in individual studies, our main statistic of interest “lag time to benefit” (that is, the number of years until the absolute risk reduction crossed a certain threshold) was not reported by individual studies. To obtain the lag time to benefit for each study, we fit Weibull survival curves using the annual mortality data for the control and intervention groups, and we used the study specific curves to estimate annual absolute risk reductions and to determine when specific absolute risk reduction thresholds (1:5000, 1:2000, and 1:1000) were crossed. Then, with the simulated parameter values we used Markov chain Monte Carlo methods to obtain lag times and 95% intervals for individual studies.

To pool lag times to benefit from individual studies, we fit a random effects Weibull model using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, allowing both the scale and the shape parameters to vary for each arm of each study.26 Using 100 000 Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations, we obtained point estimates, standard errors, and confidence intervals for annual mortality rates in control and intervention patients for each individual study and for the random effects meta-analysis model. From this model we obtained pooled estimates of annual absolute risk reduction as well as pooled estimates of time until specific absolute risk reduction thresholds (1:5000, 1:2000, and 1:1000) were crossed. We performed Markov chain Monte Carlo computations using the Markov chain Monte Carlo procedure in SAS for the individual Weibull curves and OpenBUGS/BRugs for the random effects Weibull model (see appendices 6 and 7 on bmj.com). We utilized similar methods to determine the time to benefit for screening fecal occult blood testing and screening mammography in a previously published study.22

Results

We identified four population based randomised controlled trials that met our inclusion criteria (total n=459 814). All four trials were large, ranging in size from 34 272 to 170 432 participants (table 1). Enrollment criteria were similar in all four trials: two of these trials enrolled people aged 55 to 64 years, one trial between the ages 55 and 74 years, and one between the ages 50 and 64 years. Three of the trials used a questionnaire to identify interested respondents, who were subsequently randomized to receive an invitation to screen versus usual care. One trial used a population registry to identify participants and randomize them to receive an invitation to screen versus usual care. This trial used one time flexible sigmoidoscopy screening and a combination of once only flexible sigmoidoscopy and immunological fecal occult blood testing. Two trials used one time flexible sigmoidoscopy screening; one trial had a second round of screening 3-5 years after the first screening. The four studies had similar length of follow-up, ranging from 11.2 to 11.9 years. The relative risk for colorectal cancer mortality was similar for the four studies, ranging between 0.69 and 0.78 with flexible sigmoidoscopy screening.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Studies | Country | Sample size (No) | Age range (years) | Enrollment period | Follow-up (years) | Relative risk (95% CI) | CRC mortality risk per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | ARR per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |||||||||

| Segnan et al 201115 | Italy | 34 272 | 55-64 | 1995-99 | 11.4 | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.08) | 44 (36 to 55) | 35 (27 to 44) | 9.8 (−3 to 22) | Once only lifetime FS |

| Schoen et al 201214 | USA | 154 900 | 55-74 | 1993-2001 | 11.9 | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88) | 39 (35 to 43) | 29 (25 to 32) | 10 (5 to 15) | FS at baseline, another screening 3 or 5 years later |

| Atkin et al 201012 | UK | 170 432 | 55-64 | 1994-99 | 11.2 | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.82) | 52 (48 to 56) | 36 (31 to 41) | 16 (10 to 22) | Once only lifetime FS |

| Holme et al 201413 | Norway | 100 210 | 50-64 | 1999-2001 | 11.2 | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.94) | 43* (39 to 47) | 31* (24 to 38) | 11.7 (3 to 20) | Once only lifetime FS or once only lifetime FS and FOBT |

CRC=colorectal cancer;ARR=absolute risk reduction; FS=flexible sigmoidoscopy; FOBT=fecal occult blood testing

*Mortality rates are age adjusted rates reported by authors. The 95% confidence intervals are calculated using unadjusted data reported in the original publication.

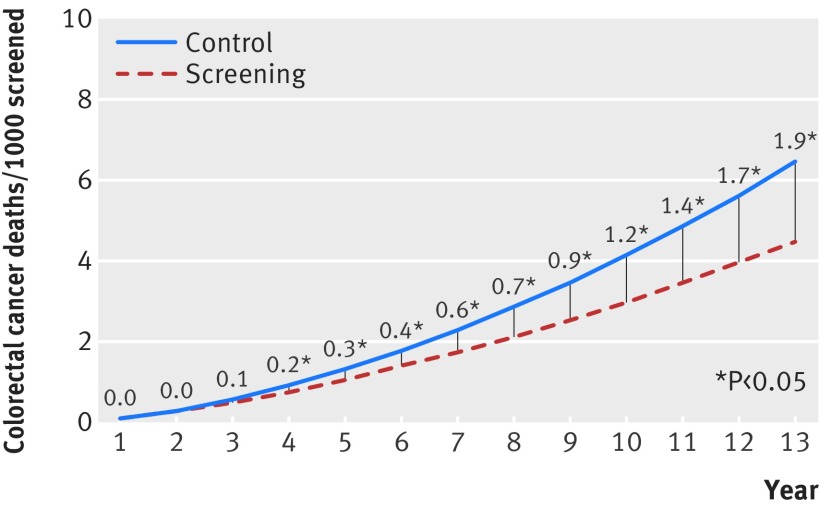

Our survival meta-analysis suggested that for every 1000 people screened 0.3 colorectal cancer related deaths were prevented at five years (figure). The benefit in colorectal cancer mortality increased steadily with longer follow-up, reaching 1.2 colorectal cancer related deaths prevented at 10 years for every 1000 people screened.

Pooled mortality curves for colorectal cancer. Values are number of deaths from colorectal cancer prevented per 1000 people screened (absolute risk reduction). *P<0.05.

We determined that it took 4.3 years (95% confidence interval 2.8 to 5.8) to prevent one colorectal cancer related death per 5000 people screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy (absolute risk reduction 0.0002, table 2). Similarly, it took 9.4 years (95% confidence interval 7.6 to 11.3) to prevent one colorectal cancer related death per 1000 people screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy (absolute risk reduction 0.001).

Table 2.

Time to benefit (years) at specific thresholds of absolute risk reduction for colorectal cancer screening

| Studies | Absolute risk reduction (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold 0.0002 | Threshold 0.0005 | Threshold 0.001 | |

| Segnan et al 201115 | 6.0 (1.4 to 16.7) | 8.4 (2.9 to 19.2) | 11.4 (4.9 to 22.7) |

| Schoen et al 201214 | 4.6 (2.3 to 8.5) | 7.3 (4.6 to 11.1) | 10.8 (7.5 to 15.1) |

| Atkin et al 201012 | 3.8 (2.2 to 6.0) | 5.9 (4.2 to 8.2) | 8.6 (6.5 to 11.2) |

| Holme et al 201413 | 5.6 (2.7 to 10.3) | 7.5 (4.7 to 11.4) | 9.8 (6.8 to 13.5) |

| Summary | 4.3 (2.8 to 5.8) | 6.6 (5.1 to 8.2) | 9.4 (7.6 to 11.3) |

Discussion

In this survival meta-analysis of screening flexible sigmoidoscopy for colorectal cancer, we quantified the time to benefit, determining when specific thresholds of mortality reduction were reached. Overall, to avoid one death from colorectal cancer using flexible sigmoidoscopy, 5000 people would need to be screened over 4.3 years and 1000 people over 9.4 years.

Implications for colorectal cancer screening

Different clinicians and patients may have differing perspectives on the specific future mortality risk reduction that justifies the immediate risks and burdens of screening. Some may view an absolute risk reduction of one death prevented per 5000 people screened as a meaningful benefit that is worth the burdens of screening and the small risk of immediate serious complications. Other patients who prefer to avoid procedures may view a 1 in 5000 benefit as small and not worth the risks and burdens of screening. Since the decision to screen or not depends in part on an individual patient’s values and how comfortable he or she is in undergoing procedures, we present a range of absolute risk reduction thresholds to inform clinicians and patients so they can individualize decisions about screening for colorectal cancer.

For screening flexible sigmoidoscopy, systematic reviews suggest that 3 in 10 000 procedures (95% confidence interval 1 to 19 per 10 000 procedures) had serious complications.27 28 Further, in the four trials in this review 5-22% of patients who had screening flexible sigmoidoscopy required a follow-up colonoscopy.12 13 14 15 For those referred to colonoscopy, systematic reviews suggest that 3 in 1000 (95% confidence interval 2 to 6) people will experience serious complications.27 Overall, this indicates that serious complications will be experienced by nearly 1 in 1000 people who undergo screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Therefore, for the average patient at risk, we believe an absolute risk reduction of 1 in 1000 (one colorectal cancer related death prevented per 1000 people screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy) is a reasonable threshold where the potential benefits likely outweigh the potential risks.

To target screening to those patients most likely to benefit, we suggest that flexible sigmoidoscopy should be recommended to patients with a life expectancy greater than the time to benefit for an absolute risk reduction of 1 in 1000.29 For older adults, potentially useful tools to estimate life expectancy are the validated mortality risk calculators available at www.eprognosis.com. We recommend screening flexible sigmoidoscopy for patients whose life expectancy substantially exceeds 10 years, since the benefits of screening seem to outweigh the risks. Conversely, for patients with a life expectancy substantially less than 10 years, we would not recommend screening flexible sigmoidoscopy since the risks of screening seem to outweigh the benefits. For patients with a life expectancy around 10 years, the risks and benefits of screening flexible sigmoidoscopy are similar in magnitude, suggesting that patient values and preferences should play a dominant role in decisions about screening.29

Comparison with other studies

Previous research supports our finding that it takes many years for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy to reduce colorectal cancer related mortality. Our previous survival meta-analysis of the time to benefit for fecal occult blood testing suggested that it would take 10 years (95% confidence interval 6 to 16) to avoid one death from colorectal cancer per 1000 people screened.30 Our current study shows that the time to benefit with flexible sigmoidoscopy is similar to that for fecal occult blood testing. While fecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy may detect different types of lesions, positive results from either screening test leads to colonoscopy, suggesting that the time to benefit for colonoscopy may be approximately 10 years.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our results should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. A major strength is that this is the first study to use quantitative methods to meta-analyze randomized controlled trials to determine times to benefit for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy.

One important limitation is our focus on screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Although colonoscopy is the common modality for colorectal cancer screening in North America, screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is becoming more widely available in the United Kingdom as part of the bowel cancer screening program.19 Further, randomized controlled trials for screening colonoscopies will not yield published results for another 7-12 years, suggesting that flexible sigmoidoscopy will likely remain an important screening modality in many countries for many years.16 17 18

A second limitation is that there is much uncertainty around the rates of serious complications from screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. A systematic review estimated a 48-fold difference between the upper and lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for rates of serious complications from flexible sigmoidoscopy.27 Because of the uncertainty surrounding the frequency of harms, it is unclear what level of delayed benefit would justify exposing patients to those immediate harms. Thirdly, meta-analysis results from combining a small number of studies may be sensitive to the choice of meta-analytic methods. However, our results were consistent across both fixed and random effects meta-analyses. Fourthly, our analysis is limited to mortality benefit of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer; it does not deal with the effects of screening flexible sigmoidoscopy on incidence of colorectal cancer.

Future research should explore the effect of screening on disability adjusted life years to further characterize the balance of benefits and harms for flexible sigmoidoscopy screening. Finally, our analysis relies on intention to treat analyses, which combine all participants who were invited to screening whether or not they received screening. The observed compliance rates for screening in the four trials ranged from 58-84%.12 13 14 15 Although intention to treat analyses likely provide the most unbiased population estimates of the effects of screening, they may underestimate the benefits of screening for those patients who choose to be screened.

Conclusion and policy implications

It takes nearly 10 years after screening flexible sigmoidoscopy to observe an absolute risk reduction in colorectal cancer related mortality of 0.001. This suggests that screening flexible sigmoidoscopy should be targeted to those older adults whose life expectancy exceeds 10 years.

What is already known on this topic

Guidelines recommend targeting cancer screening to older adults (50-74 years) whose life expectancy exceeds the time to benefit for screening

What this study adds

This study found that it would take 9.4 years for one colorectal cancer related death to be prevented for every 1000 people screened

This finding suggests that flexible sigmoidoscopy screening should be targeted towards patients with a life expectancy of greater than 10 years

We thank Nereo Segnan who provided data from the Italian SCORE (Screening for COlonREctum) study of screening flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Contributors: VT led the drafting of the manuscript. WJB led the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation. IS-C analysed and interpreted the data. SJL designed and supervised the study. All authors contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. VT and SJL are the guarantors.

Funding: SJL was supported by the Beeson career development award through the American Federation of Aging Research and National Institute on Aging (K23AG040779). The funding source had no involvement in the design or conduct of the study and had no influence on the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The full dataset for meta-analysis is available in appendix 4 on bmj.com.

Transparency: The lead author (VT) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h1662

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary information

References

- 1.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kewenter J, Brevinge H, Engaras B, et al. Results of screening, rescreening, and follow-up in a prospective randomized study for detection of colorectal cancer by fecal occult blood testing. Results for 68,308 subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol 1994;29:468-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronborg O, Jorgensen OD, Fenger C, et al. Randomized study of biennial screening with a faecal occult blood test: results after nine screening rounds. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:846-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller AD, Sonnenberg A. Protection by endoscopy against death from colorectal cancer. A case-control study among veterans. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholefield JH, Moss S, Sufi F, et al. Effect of faecal occult blood screening on mortality from colorectal cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2002;50:840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiis-Evensen E, Hoff GS, Sauar J, et al. Population-based surveillance by colonoscopy: effect on the incidence of colorectal cancer. Telemark Polyp Study I. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:414-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. New Engl J Med 1993;329:1977-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkin WS, Hart A, Edwards R, et al. Uptake, yield of neoplasia, and adverse effects of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening. Gut 1998;42:560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kewenter J, Brevinge H. Endoscopic and surgical complications of work-up in screening for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39:676-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH Jr, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:378-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:1624-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holme O, Loberg M, Kalager M, et al. Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:606-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. New Engl J Med 2012;366:2345-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segnan N, Armaroli P, Bonelli L, et al. Once-only sigmoidoscopy in colorectal cancer screening: follow-up findings of the Italian Randomized Controlled Trial—SCORE. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1310-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Veterans Affairs. Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM). 2012. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01239082.

- 17.Kaminski MF, Bretthauer M, Zauber AG, et al. The NordICC Study: rationale and design of a randomized trial on colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 2012;44:695-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. New Engl J Med 2012;366:697-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UK Department of Health. Improving outcomes: a strategy for cancer. 2011. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213785/dh_123394.pdf.

- 20.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, et al. Comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy: a new tool to inform recommendations for optimal screening strategies. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:667-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, et al. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2012;307:182-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, et al. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ 2013;346:e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holme O, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, et al. Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:CD009259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messori A, Trippoli S, Vaiani M, et al. Survival meta-analysis of individual patient data and survival meta-analysis of published (aggregate) data. Clin Drug Investig 2000;20:309-16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Earle CC, Wells GA. An assessment of methods to combine published survival curves. Med Decis Mak 2000;20:104-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouwens MJNM, Philips Z, Jansen JP. Network meta-analysis of parametric survival curves. Res Synth Methods 2011;1:258-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitlock EP, Lin J, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review. US Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews, 2008.

- 28.Croswell JM, Kramer BS, Kreimer AR, et al. Cumulative incidence of false-positive results in repeated, multimodal cancer screening. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:212-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC. Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. JAMA 2013;310:2609-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerrish CA. Purposes, values and objectives in adult education—the post-basic perspective. Nurse Educ Today 1990;10:118-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information