Abstract

Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) pathway has become standard practice for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Compared with chemotherapy, egfr tyrosine kinase inhibitors (tkis) have been associated with improved efficacy in patients with an EGFR mutation. Together with the increase in efficacy comes an adverse event (ae) profile different from that of chemotherapy. That profile includes three of the most commonly occurring dermatologic aes: acneiform rash, stomatitis, and paronychia. Currently, no randomized clinical trials have evaluated the treatments for the dermatologic aes that patients experience when taking egfr tkis. Based on the expert opinion of the authors, some basic strategies have been developed to manage those key dermatologic aes. Those strategies have the potential to improve patient quality of life and compliance and to prevent inappropriate dose reductions.

Keywords: Non-small-cell lung cancer, adverse events, acneiform rash, paronychia, stomatitis, egfr tkis

1. INTRODUCTION

Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc) with oral agents that target the epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) pathway has become a standard therapy for patients whose tumours have an EGFR gene mutation1. The egfr tyrosine kinase inhibitors (tkis) block the adenosine triphosphate binding site of the intracellular kinase domain of egfr and prevent phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting signal transduction and subsequent cell growth and proliferation2–4.

Two types of egfr tkis have been developed: reversible and irreversible egfr tkis. Two reversible egfr tkis are currently approved by Health Canada for the treatment of patients with advanced nsclc: gefitinib is approved in the first-line setting for patients whose tumours are EGFR–mutation positive, and erlotinib is approved in the second- and third-line settings in unselected patients after chemotherapy failure1. Gefitinib and erlotinib compete reversibly for the adenosine triphosphate binding site of the kinase domain of egfr. After treatment with a reversible egfr tki, patients frequently become resistant to those agents because of a secondary mutation in the receptor’s tyrosine kinase domain. In approximately half the cases of acquired resistance, the cause is a missense T790M mutation4.

To overcome resistance, the newer egfr tkis that have been developed bind irreversibly to the active site of the kinase domain. The newer agents include afatinib and dacomitinib. Afatinib is an ErbB family blocker that has been shown to be highly selective for egfr, her2 (the human epidermal growth factor receptor, ErbB2), and her4 (ErbB4)5,6. Afatinib is approved by Health Canada as monotherapy in egfr tki–naïve patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma who have an activating EGFR mutation. Like afatinib, dacomitinib is an irreversible pan-ErbB inhibitor that targets egfr, her2, and her47.

The primary dermatologic adverse event (ae) associated with reversible and irreversible egfr tkis is acneiform rash2, which is characterized by an eruption of papules and pustules that typically appear on the face, scalp, upper chest, and back8. Additional aes that are more commonly associated with irreversible egfr tkis are paronychia and stomatitis or mucositis9. Paronychia is a disorder characterized by an inflammatory process involving the soft tissues around the nails8. Stomatitis and mucositis are terms that are frequently used interchangeably. However, mucositis refers to an inflammation of the entire gastrointestinal tract; stomatitis refers specifically to inflammation of the oral mucosa8,10.

Available evidence suggests that the severity of skin toxicity correlates positively with a response to therapy with egfr tkis11–13. In the phase ii ideal study, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of gefitinib in pretreated patients with nsclc, skin toxicity was reported by 86% of patients who experienced symptom improvement and by 58% of patients who experienced no symptom improvement14. A retrospective analysis of patients treated under the gefitinib Expanded Access Program showed that median survival was 10.8 months in patients who experienced a skin rash compared with just 4.0 months in patients not experiencing a skin rash (p < 0.0001)12,15.

Similar results were seen in a retrospective study of erlotinib: after controlling for baseline factors, overall survival and progression-free survival showed a strong, positive correlation with the presence of rash—a correlation that increased with rash severity12,16. The positive correlation between skin toxicity and clinical response suggests that rash could be a marker of egfr tki efficacy or adequate dosing.

2. PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS OF EGFR TKI INHIBITION

The egfr is critical in the physiology and development of the epidermis, which is composed primarily of keratinocytes9. Undifferentiated proliferating keratinocytes, including those in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epidermis, express egfr, which stimulates epidermal growth, promotes differentiation, and accelerates wound healing. Use of an egfr tki affects epidermal-derived tissues; effects include impaired keratinocyte growth, migration, and chemokine expression, which leads to inflammatory cell recruitment and cutaneous injury, including symptoms of rash and periungual inflammation. Those effects result from inhibition of pathways downstream of egfr, such as the mapk pathway1,17.

2.1. Incidence of Dermatologic AEs

In phase iii clinical trials, the incidence of acneiform rash varied from 37% to 76% in patients treated with reversible egfr tkis and from 69% to 89% in patients treated with the irreversible egfr tki afatinib (Table i). In phase ii trials with dacomitinib, the incidence of acneiform rash was comparable to that in the phase iii afatinib trials. In the case of gefitinib, the incidence of rash appeared to be related to dose. The incidence of stomatitis or mucositis in patients participating in phase iii clinical trials of reversible egfr tkis varied from 6% to 19%. However, the incidence was higher in phase iii clinical trials of afatinib, ranging from 51% to 72%. Similarly, the incidence of paronychia or nail effects was lower with gefitinib (3%–14% of patients) than with afatinib (33%–57% of patients). The higher incidence of dermatologic aes seen with irreversible egfr tkis might be attributable to the covalent bond formed between the tki and egfr, which prolongs the effect of the tki6.

TABLE I.

Incidence of three adverse events accompanying the administration of epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr ) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (tki s) in selected clinical trials in non-small-cell lung cancera

| egfr tki and dose | Study type and dose | Incidence of adverse event by grade (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Acneiform rash | Stomatitis or mucositisb | Paronychia or nail effectsb | |||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | ||

| Erlotinib 150 mg |

All | 33–79 | 3–10 | 9–19 | <1–32 | 15 | 0 |

| Phase iii | 62–76 | 7–10 | 19 | <1 | nr | nr | |

| Gefitinib 250 mg and 500 mg |

All | 34–75 | 0–13 | 6–17 | <1 | 3–14 | <1 |

| 250 mg | 34–66 | 0–4 | 6–17 | <1 | 3–14 | <1 | |

| 500 mg | 57–75 | 4–13 | nr | nr | nr | nr | |

| Phase iii | |||||||

| 250 mg | 37–66 | 2–4 | 6–17 | 0–3 | 3–14 | 0–1 | |

| 500 mg | 57–67 | 12–13 | nr | nr | nr | nr | |

| Afatinib 40 mg and 50 mg |

All | 69–94 | 7–28 | 50–90 | 0–10 | 33–85 | 0–11 |

| 40 mg | 69–90 | 7–16 | 50–72 | 0–9 | 33–80 | 0–11 | |

| 50 mg | 78–94 | 14–28 | 61–90 | 3–10 | 39–86 | 5–8 | |

| Phase iii | |||||||

| 40 mg | 69–89 | 10–16 | 51–72 | 5–9 | 33–57 | 0–11 | |

| 50 mg | 78 | 14 | 61 | 3 | 39 | 5 | |

| Dacomitinib 30 mg and 45 mg |

All | 68–100 | 0–15 | 15–46 | 0–3 | nr | nr |

| 30 mg | 69 | 0 | 15 | 0 | nr | nr | |

| 45 mg | 68–100 | 15 | 46 | 3 | nr | nr | |

In the lux-Lung 3 trial of afatinib compared with pemetrexed–cisplatin chemotherapy, the all-grade incidences of acneiform rash, stomatitis or mucositis, and paronychia (89.1%, 72.1%, and 56.8% respectively) were higher than the all-grade incidences of the same aes reported in the lux-Lung 6 trial (80.8%, 51.9%, and 32.6% respectively), which compared afatinib with gemcitabine–cisplatin chemotherapy50,51. The differences in the two trials were the ethnic origins of the patient populations and the types of chemotherapy given, which would not affect the ae profile for patients in the afatinib arm. A recent analysis analyzed the incidence of the aes in the two trials by ethnicity: the patient population in lux-Lung 3 was approximately 72% East Asian, 26% white, and 2% other; the patient population in lux-Lung 6 was entirely Asian50,51. Overall rates of stomatitis or mucositis (65.3% vs. 39.1%) and paronychia (45.8% vs. 35.9%) were higher in Asian than in non-Asian patients. However, the rates of grade 3 events were low and comparable between those groups56.

2.2. Acneiform Rash

2.2.1. Assessment and Grading

Acneiform rash usually develops in stages. In week 1, the patient experiences sensory disturbance, erythema, and edema; a papulopustular eruption follows in week 2. In week 4, crusting occurs, and in weeks 4–6, if the rash has been treated successfully, a background of erythema and dry skin occurs where papulopustular eruptions had previously been seen1. Rash typically occurs on the face, shoulders, upper back, and upper chest. However, dry itchy skin can occur on the arms and legs of approximately 35% of patients and can become infected with the herpes simplex virus or Staphylococcus aureus11. Acneiform rash seems to dissipate entirely once the egfr tki is discontinued11,12.

For the first 6 weeks, patients should be closely followed each week and should contact their health care provider if rash becomes problematic. Patient education about egfr tki–induced rash should ideally begin before treatment initiation and continue throughout treatment. It is important to tell patients that egfr tki–induced rash is a common ae and that it might indicate efficacy of treatment. To prevent dose reduction or discontinuation of the egfr tki, it is important that patients know to report and obtain early treatment for rash2. The impact of dose reduction on the clinical course of skin lesions has not been published and requires further investigation57.

The most common grading system for acneiform rash is the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events8 (Table ii, Figure 1). The grade is determined in part by the percentage of body surface area covered in papules or pustules. Other considerations are psychosocial impact, extent of superinfection, and interference with daily activities. Grade 4 is considered life-threatening, and grade 5 is death.

TABLE II.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system for acneiform rash8

| Grade 1 |

|

| Grade 2 |

|

| Grade 3 |

|

| Grade 4 |

|

| Grade 5 |

|

FIGURE 1.

Acneiform rash induced by epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. (A) Grade 1, gefitinib. (B) Grade 2, erlotinib. (C) Grade 3, erlotinib. (D) Grade 4, erlotinib.

2.2.2. Management

Prophylactic Management Strategies:

Two randomized double-blind studies whose goal was to determine if prophylactic tetracycline diminished the severity of egfr tki–induced rash have been completed. The studies compared tetracycline (500 mg twice daily) given prophylactically (that is, before the egfr tki was started) with placebo58,59. The results of the studies showed that tetracycline did not prevent rash, reduce rash severity, or improve quality of life. Another study, the Pan-Canadian Rash Trial (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00473083), investigated whether prophylactic minocycline has an effect on the overall incidence of rash. Patients starting erlotinib were randomized to receive prophylactic minocycline for 4 weeks, rash treatment according to grade, or no treatment unless rash was severe. Preliminary analysis suggested that prophylactic minocycline treatment does not affect efficacy outcomes and is associated with a decrease in severe rashes, making prophylactic minocycline an option for the management of egfr tki–induced rash.

Preventive Management Strategies:

A number of preventive measures can be taken to reduce the risk of egfr tki–induced acneiform rash. Patients should be instructed to apply an alcohol- and perfume-free emollient cream twice daily, preferably to the entire body. Creams and ointments are preferred over lotions, because lotions could contain alcohol. Sunscreen should be applied to sun-exposed areas twice daily to prevent sunburn or excess sun exposure, which can worsen symptoms of rash. Finally, hot showers and products that dry the skin should be avoided1,2.

Pharmacologic Management Strategies:

Treatment algorithms for egfr tki–induced acneiform rash vary widely between the expert centres using those agents. Hydrocortisone 1% cream is commonly found in treatment algorithms for rash. However, if it is insufficient, use of a higher-potency topical steroid—such as hydrocortisone valerate twice daily as needed for grades 1–3 rash—can be helpful (Table iii). In addition, for grades 2 and 3 acneiform rash, oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily for 4 weeks) should be added to the treatment regimen1.

TABLE III.

Treatment algorithm for acneiform rash

| Mild (grade 1) |

|

| Moderate (grade 2) |

|

| Severe (grade 3) |

|

The dose of egfr tki should be maintained through grade 2 acneiform rash. However, for prolonged grade 2 rash, the egfr tki can be temporarily discontinued until symptoms improve to grade 1 or less; it can then be reintroduced at a dose of the physician’s discretion. If rash progresses to grade 3, the egfr tki should be temporarily discontinued (2–4 weeks) and then reintroduced at a dose of the physician’s discretion. If no improvement occurs, the egfr tki should be discontinued1.

2.3. Stomatitis or Mucositis

2.3.1. Assessment and Grading

Before the start of treatment with an egfr tki, the patient’s oral cavity should be assessed to obtain a baseline for any changes that might occur with therapy10. Oral mucositis can occur as broad areas of erythema or aphthous-like stomatitis9. Stomatitis usually starts with asymptomatic redness and erythema; it can progress to the formation of white patches associated with minimal pain, eventually transitioning to acutely painful large continuous lesions10. Based on the clinical experience of the authors, abnormal tingling sensations in the mouth are often reported within the first week of treatment with an egfr tki.

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system sets out five grades of oral mucositis (Table iv, Figure 2)8. Grade 1 is characterized as asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, and grade 2 as moderate pain that does not interfere with eating and drinking. By grade 3, patients can experince severe pain that interferes with intake of food and drink, followed by grade 4, which is considered life-threatening. Grade 5 is death.

TABLE IV.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system for oral mucositis8

| Grade 1 | • Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; intervention not indicated. |

| Grade 2 | • Moderate pain; not interfering with oral intake; modified diet indicated. |

| Grade 3 | • Severe pain; interfering with oral intake. |

| Grade 4 | • Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated. |

| Grade 5 | • Death |

FIGURE 2.

Stomatitis or mucositis induced by epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. (A) Grade 1, afatinib. (B) Grade 2, afatinib. (C) Grade 3, afatinib.

2.3.2. Management

Oral Hygiene:

After an initial assessment of oral health before the start of therapy with an egfr tki, the oral cavity should be evaluated by a health care professional periodically throughout treatment and at treatment completion9.

A simple oral care regimen for patients includes brushing the teeth and tongue with a soft-bristle brush, flossing, rinsing (preferably with normal saline), and moisturizing. If unable to use a toothbrush, patients can use a foam swab [for example, Toothette (Sage Products, Cary, IL, U.S.A.)] or piece of gauze, which are softer and less abrasive. Commercial mouthwashes often contain alcohol, which can irritate and dry the mucosal tissue; they should be avoided10. For mild stomatitis, a patient should perform oral care every 2–3 hours; for patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms, oral care should be performed every 1–2 hours10.

Pharmacologic Management Strategies:

No randomized controlled trials have evaluated treatment for egfr tki–induced stomatitis or mucositis, which can range from painful lesions to general mouth sensitivity9. The recommendations in the treatment algorithm (Table v) are based on the expert opinion of the authors.

TABLE V.

Treatment algorithm for stomatitis or mucositis

| Mild (grade 1) |

|

| Moderate (grade 2) |

|

| Severe (grade 3) |

|

For general mouth sensitivity, patients can gargle with Tantum [benzydamine rinse (Angelini, Ancona, Italy): 15 mL for 30 seconds and spit out] 3 times daily as needed. Treatment for grade 1 stomatitis or mucositis is triamcinolone in dental paste applied 2–3 times daily as necessary, a therapy that is also used to reduce pain and inflammation from aphthous ulcers60. Treatment for grade 2 stomatitis includes the same regimen of triamcinolone in dental paste, with the addition of either oral erythromycin (250–350 mg daily) or minocycline (50 mg daily). For grade 3, clobetasol ointment is used instead of triamcinolone in dental paste, and the erythromycin dose is increased to 500 mg daily or the minocycline dose to 100 mg.

As with acneiform rash, the dose of egfr tki is maintained for grades 1 and 2 stomatitis; the egfr tki is temporarily discontinued (2–4 weeks) for grade 3 events. Upon improvement to grade 2 or less, the egfr tki can be reintroduced at a dose of the physician’s discretion. However, if no improvement is seen, the egfr tki should be discontinued.

2.4. Paronychia

2.4.1. Assessment and Grading

Acneiform rash typically appears early in treatment, but paronychial inflammation occurs after a longer period (that is, after several weeks or months of egfr tki therapy)1,61. Nail changes are usually mild, but can also be symptomatic and severe1,62. Paronychia affects the nails of the fingers and toes, most commonly occurring on the first digits9.

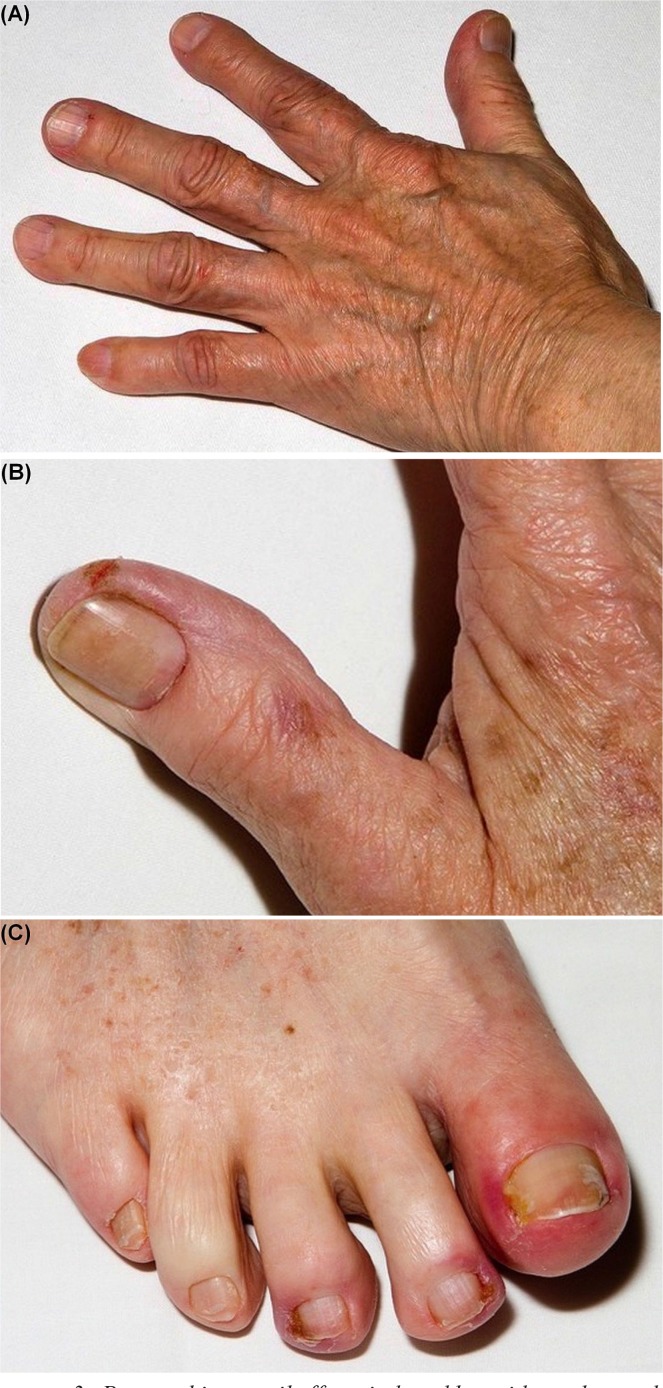

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system for paronychia ranges from grade 1 to grade 3, instead of grades 1–5 (Table vi, Figure 3)8. Grade 1 paronychia is associated with nailfold edema or erythema and cuticle disruption. By grade 2, the nailfold edema or erythema is associated with pain. In grade 2 paronychia, discharge or nail-plate separation can also occur, and instrumental activities of daily living are limited. Local or oral intervention is indicated. Grade 3 paronychia is characterized by limitations in self-care activities of daily living, and surgical intervention could be indicated.

TABLE VI.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system for paronychia8

| Grade 1 |

|

| Grade 2 |

|

| Grade 3 |

|

| Grade 4 | — |

| Grade 5 | — |

FIGURE 3.

Paronychia or nail effects induced by epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. (A) Grade 1, erlotinib. (B) Grade 2, afatinib. (C) Grade 3, erlotinib.

2.4.2. Management

As for stomatitis, no randomized controlled trials have evaluated treatments for paronychia. The recommendations in the treatment algorithm (Table vii) are based on the expert opinion of the authors.

TABLE VII.

Treatment algorithm for paronychia

| Local care |

|

| Mild-to-moderate (grade 1 or 2) |

|

| Severe (grade 3) |

|

Local Care Strategies:

Local care strategies to manage paronychia include emolliation with petroleum jelly, cushioning of affected areas, nail trimming (no aggressive manicures), and the use of gloves when cleaning to avoid irritants. Antimicrobial soaks (for example, diluted white vinegar or diluted bleach in water) are recommended to help prevent superinfection9.

Pharmacologic Management Strategies:

In the general population, acute paronychia is typically associated with S. aureus infection, and chronic paronychia is usually associated with Candida albicans (or Monilia) infection63, indicating a potential need for antibiotic or antifungal interventions8. However, egfr tki– associated paronychia is sterile and corresponds with an ungual-fold inflammation consisting primarily of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils64,65. To treat this type of paronychial inflammation, beta-methasone valerate for grades 1 and 2 and clobetasol cream for grade 3 should be applied 2 or 3 times daily as needed. If paronychia reaches grade 3, the egfr tki should be temporarily discontinued (2–4 weeks) until symptoms improve to grade 1 or less, when the drug can be reintroduced at a dose of the physician’s discretion. If no improvement is seen during the temporary discontinuation period, the egfr tki should be stopped altogether. In cases of refractory paronychia, or if signs of a superinfection are present, topical antibiotics such as mupirocin ointment can be used.

3. SUMMARY

Three of the most common dermatologic aes associated with egfr tki therapy are acneiform rash, stomatitis, and paronychia. These dermatologic aes can be significant and debilitating and can have a negative effect on the patient’s quality of life57,65. The potential for reduced treatment compliance resulting from egfr tki–induced aes can complicate disease management, especially given that the severity of some of the aes appears to correlate with treatment response65. Current ae management strategies have been developed based on physician experience. However, as treatment with targeted agents becomes more common for patients with nsclc, the most effective interventions for dermatologic aes will need to be determined through rigorous, systematic evaluation, so as to ensure patient compliance and improve quality of life.

4. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge medical writing support from Cathie Bellingham phd of New Evidence, which was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada).

5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare the following interests: BM has received honoraria for advisory board participation from Eli Lilly, Hoffmann–La Roche, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. JR has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. KP has consulted for and received payment from 3M, Abbott, Akesis, Akros, Alza, Amgen, Astellas, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Centocor, Cipher, Eli Lilly, Forward Pharma, Isotechnika, Janssen, Janssen Biotech (Centocor), Johnson and Johnson, Kataka, Kirin, Kyowa, Lypanosys, Meiji Seika Pharma, Medical Minds, Merck, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, UCB, Vertex, and Wyeth. DS has consulted for, or been on the advisory boards of, Easton Associates, SAIC, Trinity Partners, Coleman Research Group, Frankel Group, Align2Action, Amgen Canada, Hoffmann–La Roche Canada, Pfizer Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim Canada, Transport Canada, and Guidepoint Global/Warburg Pincus; has had grants paid to his institution from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Defense, AstraZeneca, Hoffmann–La Roche Canada, and Pfizer Canada; has been a speaker for Pfizer Canada, AstraZeneca Taiwan, University of Michigan/swog, Ventana, iaslc, University of Texas San Antonio, American Radium Society, and the 5th International Pulmonary Congress; and has received royalties from Springer. NBL and RS have no conflicts of interest to declare.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Melosky B. Supportive care treatments for toxicities of anti-egfr and other targeted agents. Curr Oncol. 2012;19(suppl 1):S59–63. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsh V. Managing treatment-related adverse events associated with egfr tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:126–38. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase ii trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (the ideal 1 trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4863] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belani CP. The role of irreversible egfr inhibitors in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: overcoming resistance to reversible egfr inhibitors. Cancer Invest. 2010;28:413–23. doi: 10.3109/07357901003631072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible egfr/her2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–11. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsh V. Afatinib (BIBW 2992) development in non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7:817–25. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramalingam SS, Blackhall F, Krzakowski M, et al. Randomized phase ii study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible pan-human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3337–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States, Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute(nci) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Ver. 4.03. Bethesda, MD: NCI; 2010. [Available online at: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf; cited April 29, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, et al. on behalf of the mascc Skin Toxicity Study Group Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of egfr inhibitor–associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079–95. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CG, Yoder LH. Stomatitis: an overview: protecting the oral cavity during cancer treatment. Am J Nurs. 2002;102(suppl 4):20–3. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200204001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harandi A, Zaidi AS, Stocker AM, Laber DA. Clinical efficacy and toxicity of anti-egfr therapy in common cancers. J Oncol. 2009;2009:567486. doi: 10.1155/2009/567486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovannini M, Gregorc V, Belli C, et al. Clinical significance of skin toxicity due to egfr-targeted therapies. J Oncol. 2009;2009:849051. doi: 10.1155/2009/849051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez–Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A, et al. her1/egfr inhibitor–associated rash: future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the her1/egfr inhibitor rash management forum. Oncologist. 2005;10:345–56. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-5-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed MK, Ramalingam S, Lin Y, Gooding W, Belani CP. Skin rash and good performance status predict improved survival with gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:780–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, Witt K, Clark G, Cagnoni PJ. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase iii studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3913–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacouture ME, Basti S, Patel J, Benson A., 3rd The series clinic: an interdisciplinary approach to the management of toxicities of egfr inhibitors. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:236–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. on behalf of the tribute Investigator Group tribute: a phase iii trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5892–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. on behalf of the ncic Clinical Trials Group Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho BC, Im CK, Park MS, et al. Phase ii study of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2528–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase iii study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1545–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, et al. Phase ii clinical trial of chemotherapy-naïve patients >or= 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:760–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felip E, Rojo F, Reck M, et al. A phase ii pharmacodynamic study of erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3867–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lilenbaum R, Axelrod R, Thomas S, et al. Randomized phase ii trial of erlotinib or standard chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:863–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok TS, Wu YL, Yu CJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase ii study of sequential erlotinib and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5080–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennouna J, Besse B, Leighl NB, et al. Everolimus plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc) [abstract 419P] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii140. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groen HJM, Socinski M, Grossi F, et al. Randomized phase ii study of sunitinib (su) plus erlotinib (e) vs. placebo (p) plus e for treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc) [abstract 417P] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii139. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly K, Azzoli CG, Patel JD. Randomized phase iib study of pralatrexate vs. erlotinib in patients with stage iiib/iv non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc) after failure of prior platinum-based therapy [abstract LBA17] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824cc66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scagliotti GV, Krzakowski MJ, Szczesna A. Sunitinib (su) in combination with erlotinib (e) for the treatment of advanced/metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer (nsclc): a phase iii study [abstract LBA6] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii3. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao HY, Gongyan C, Feng J, et al. A phase ii study of erlotinib plus capecitabine (xel) as first line treatment for Asian elderly patients (pts) with advanced adenocarcinoma of lung (ML 22206 study) [abstract 420P] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii140. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced egfr mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (optimal, ctong-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natale RB, Thongprasert S, Greco FA, et al. Phase iii trial of vandetanib compared with erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1059–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation–positive non-small-cell lung cancer (eurtac): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, et al. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib versus chemotherapy in second-line treatment of patients with advanced, non-small-cell lung cancer with poor prognosis (titan): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:300–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, et al. on behalf of the tailor trialists Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and wild-type egfr tumours (tailor): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:981–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SM, Khan I, Upadhyay S, et al. First-line erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer unsuitable for chemotherapy (topical): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1161–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase iii trial—intact 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase iii trial—intact 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (interest): a randomised phase iii trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1809–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goss G, Ferry D, Wierzbicki R, et al. Randomized phase ii study of gefitinib compared with placebo in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and poor performance status. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2253–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surmont VF, Gaafar RM, Scagliotti GV, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase iii study of gefitinib (g) versus placebo (p) in patients (pts) with advanced nsclc, nonprogressing after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (eortc 08021-ilcp) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (wjtog3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi Y, Zhang L, Liu X, et al. Icotinib versus gefitinib in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (icogen): a randomised, double-blind phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:953–61. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (lux-Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katakami N, Atagi S, Goto K, et al. lux-Lung 4: a phase ii trial of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who progressed during prior treatment with erlotinib, gefitinib, or both. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3335–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang JC, Shih JY, Su WC, et al. Afatinib for patients with lung adenocarcinoma and epidermal growth factor receptor mutations (lux-Lung 2): a phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:539–48. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. ClinicalTrials.gov . lux-Lung 5: afatinib plus weekly paclitaxel versus investigator’s choice of single agent chemotherapy following afatinib monotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients failing erlotinib or gefitinib [clinical trial record] Bethesda, MD: ClinicalTrials.gov; 2012. [Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01085136; cited September 30, 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring egfr mutations (lux-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:213–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase iii study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with meta-static lung adenocarcinoma with egfr mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janne PA, Reckamp K, Koczywas M, et al. Efficacy and safety of PF-00299804 (PF299) in patients with advanced nsclc after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen and prior treatment with erlotinib (e): a two-arm, phase ii trial [abstract 8063] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7695. [Available online at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/32872-65; cited February 20, 2015] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mok T, Spigel DR, Park K, et al. Efficacy and safety of PF299804 as first-line treatment (tx) of patients (pts) with advanced (adv) nsclc selected for activating mutation (mu) of epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) [abstract LBA18] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi T, Boku N, Murakami H, et al. First report of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of PF299804 in Japanese patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors [abstract 533P] Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):174. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang JCH, Sequist LV, O’Byrne KJ, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr)–mediated adverse events (aes) in patients (pts) with EGFR mutation positive (EGFR M+) non-small cell lung cancer treated with afatinib [abstract 895] Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(suppl 2) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sequist LV, Yang JCH, Yamamoto N, et al. Comparative safety profile of afatinib in Asian and non-Asian patients with EGFR mutation-positive (EGFR M+) non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc) [abstract P3.11-023] J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(suppl 2):S1197. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reguiai Z, Bachet JB, Bachmeyer C, et al. Management of cutaneous adverse events induced by anti-egfr (epidermal growth factor receptor): a French interdisciplinary therapeutic algorithm. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1395–404. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jatoi A, Dakhil SR, Sloan JA, et al. on behalf of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group Prophylactic tetracycline does not diminish the severity of epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) inhibitor–induced rash: results from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (Supplementary N03CB) Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1601–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0988-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, et al. Tetracycline to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rashes: results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N03CB) Cancer. 2008;113:847–53. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark D. How do I manage a patient with aphthous ulcers? J Can Dent Assoc. 2013;79:d48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lacouture ME, Melosky BL. Cutaneous reactions to anticancer agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor: a dermatology–oncology perspective. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1113–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu JC, Sadeghi P, Pinter–Brown LC, Yashar S, Chiu MW. Cutaneous side effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:317–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peuvrel L, Bachmeyer C, Reguiai Z, et al. Semiology of skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) inhibitors. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:909–21. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]