Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have indicated that post-menopausal women have a higher incidence of intracranial aneurysms than men in the same age group.

Objective

We sought to investigate whether estrogen or estrogen receptors (ERs) mediate protective effects against the formation of intracranial aneurysms.

Methods

Intracranial aneurysms were induced in mice by combining a single injection of elastase into the cerebrospinal fluid with deoxycorticosterone acetate salt hypertension. The mice were treated with estrogen (17β-estradiol), ERα agonist (propylpyrazole-triol), and ERβ agonist (diarylpropionitrile) with and without a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor.

Results

The ovariectomized female mice had a significantly higher incidence of aneurysms than the male mice, which was consistent with past epidemiological studies. In ovariectomized female mice, an ERβ agonist, but not an ERα agonist or 17β-estradiol, significantly reduced the incidence of aneurysms. The protective effect of the ERβ agonist was absent in the ovariectomized ERβ knockout mice. The protective effect of the ERβ agonist was negated by treatment with a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor.

Conclusions

The effects of gender, menopause, and estrogen treatment observed in this animal study were consistent with previous epidemiological findings. Stimulation of estrogen receptor-β was protective against the formation of intracranial aneurysms in ovariectomized female mice.

Keywords: Stroke [50] cerebral aneurysm; AVM, and subarachnoid hemorrhage; Stroke treatment – surgical [79] Aneurysm; AVM, hematoma; Stroke treatment – medical [74] other stroke treatment/medical; Vascular biology [97] other vascular biology

Introduction

Women are known to have a higher incidence of intracranial aneurysms than men. However, epidemiological studies show that the female preponderance of intracranial aneurysms becomes significant only after the fourth or fifth decades of life, during the peri- and post-menopausal periods.1, 2 Before the fourth or fifth decades, there is no difference between men and women in the incidence of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage.1, 2 These epidemiological observations suggest the potential roles of sex steroids, particularly estrogen, in the pathophysiology of intracranial aneurysms. In post-menopausal women, a relative deficiency in estrogen may increase the risks for aneurysmal formation and growth.1–5

Previous studies have demonstrated the protective effects of estrogen against various types of vascular injury, particularly atherosclerosis.6 Estrogen exerts protective effects against vascular injury by modulating inflammation, nitric oxide production, cytokine and growth factor expression, and the reduction of oxidative stress.7 Effects of estrogen are primarily mediated by two nuclear hormone receptors (ligand-activated transcriptional factors): estrogen receptor-α and estrogen receptor-β. Both estrogen receptor-α and estrogen receptor-β are expressed in vascular cells, including endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells.

In this study, we assessed the effects of estrogen and selective estrogen receptor subtype agonists on the formation of intracranial aneurysms in female mice. We sought to investigate the receptor subtype and the underlying mechanisms that are responsible for the potentially protective effect of estrogen.

Materials and Methods

Animal model

Experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines approved by the University of California, San Francisco’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We used 10- to 12-week-old C57BL/6J mice and estrogen receptor-β knockout (ERβKO) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine). Intracranial aneurysms were induced by a combination of pharmacologically-induced hypertension and a single injection of elastase (10 milli-units) into the cerebrospinal fluid at the right basal cistern as we previously described.8–11 See Text, Supplemental Content 1, which demonstrates details of the aneurysm model. Four weeks after the aneurysm induction, we euthanized the mice and perfused the animals with bromophenol blue dye. Two blinded observers assessed the formation of intracranial aneurysms by examining the Circle of Willis and its major branches under a dissecting microscope (10X). Intracranial aneurysms were operationally defined as a localized outward bulging of the vascular wall in the Circle of Willis or in its major primary branches, as previously described.11

Treatment with estrogen, estrogen receptor-α agonist, and estrogen receptor-β agonist

In female mice, bilateral ovariectomy or sham ovariectomy was performed one week before the aneurysm induction (elastase injection). Immediately after the bilateral ovariectomy, we implanted a 60-day release pellet (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) that contained a vehicle, estrogen (17β-estradiol, 0.025 mg), propyl pyrazole triol (estrogen receptor-α agonist) (PPT, 2.5 mg), or diarylpropionitrile (estrogen receptor-β agonist) (DPN, 2.5 mg). Some of these mice received an inhibitor of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 20 mg/kg/day) in drinking water.

Statistical analysis

All of the results were expressed as mean ± SD. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the incidence of aneurysms. Differences between multiple groups were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < .05. GraphPad Prism 6 was used for statistics software.

Results

Incidence of aneurysms in male mice, female mice, ovariectomized female mice, and ovariectomized female mice with estrogen treatment

As a first step to assess the effects of gender, menopause, and estrogen on the formation of aneurysms, we compared the incidence of aneurysms in (1) male mice with sham ovariectomy (laparotomy), (2) female mice with sham ovariectomy, (3) female mice with bilateral ovariectomy (surgical menopause), and (4) ovariectomized female mice with estrogen treatment (surgical menopause + estrogen replacement).

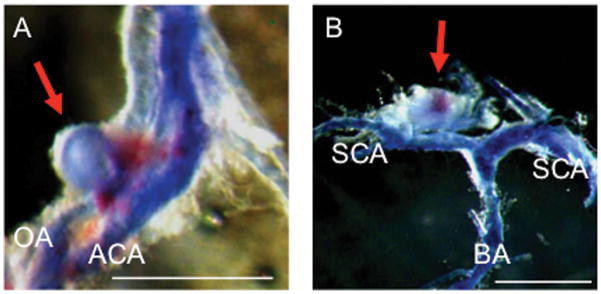

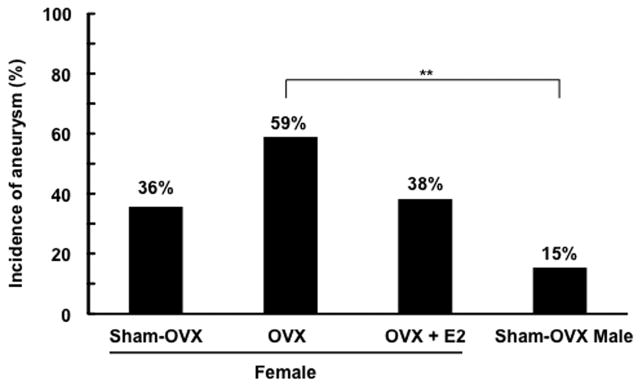

Figure 1 shows representative intracranial aneurysms that were observed in ovariectomized female mice. As shown in Figure 2, there was a trend for the bilateral ovariectomy—surgical menopause— to increase the incidence of aneurysms in female mice (59% vs. 36%, P = .05). More importantly, the ovariectomized female mice had a significantly higher incidence of aneurysms than the male mice with sham ovariectomy (59% vs. 15%, P < .01), consistent with the epidemiological studies that showed the female preponderance of aneurysms after peri-menopausal age.1, 2 There was also a trend for the estrogen treatment to reduce the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized female mice (38% vs. 59%, P = .06).

Figure 1. Representative intracranial aneurysms (arrows) in ovariectomized mice.

Aneurysm formation at the olfactory artery (A) and superior cerebral artery (B). Blood vessels were perfused with bromophenol blue. Bar=1 mm. OA: olfactory artery; ACA: anterior cerebral artery; SCA: superior cerebral artery; BA: basilar artery.

Figure 2. Incidence of intracranial aneurysms in male and female mice.

The incidence of aneurysms in female mice tended to be greater than in male mice (36 vs. 15%, P = .17). In addition, there was a strong trend for the bilateral ovariectomy (surgical menopause) to increase the incidence of aneurysms in female mice (59 vs. 36%, P = .05). Ovariectomized female mice had a significantly higher incidence of aneurysms than male mice (59 vs. 15%, P < .01). There was also a trend for the estrogen treatment to reduce the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized female mice (38 vs. 59%, P = .06)

OVX: bilateral ovariectomy. E2: estrogen treatment with 17β-estradiol.

Table in the Supplemental Content 2 demonstrates systolic blood pressure and uterine weight of each group.

Stimulation of estrogen receptor-β but not stimulation of estrogen receptor-α protects against aneurysm formation

To identify the estrogen receptor subtype that was responsible for the protective role of estrogen, we treated the ovariectomized female mice with estrogen receptor-α agonist (PPT) or estrogen receptor-β agonist (DPN). Although the treatment with estrogen receptor-α agonist did not affect the incidence of aneurysms in the ovariectomized mice, the treatment with estrogen receptor-β agonist significantly reduced the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice (26% vs. 59%, P < .05) (Figure 3).

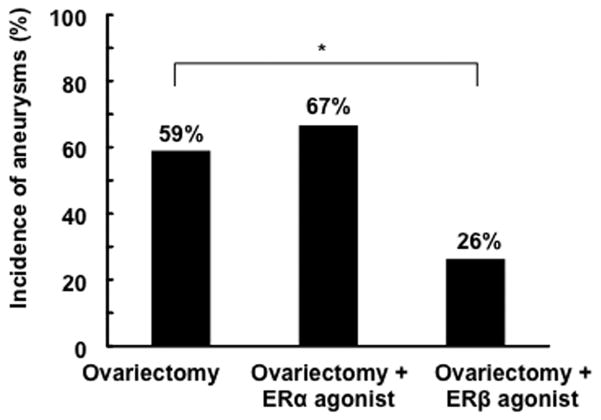

Figure 3. Effects of estrogen receptor-α agonist and estrogen receptor-β agonist on the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice.

The treatment with estrogen receptor-α agonist did not affect the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice; however, the treatment with estrogen receptor-β agonist significantly reduced the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice (26 vs. 59%, P < .05). ER: estrogen receptor

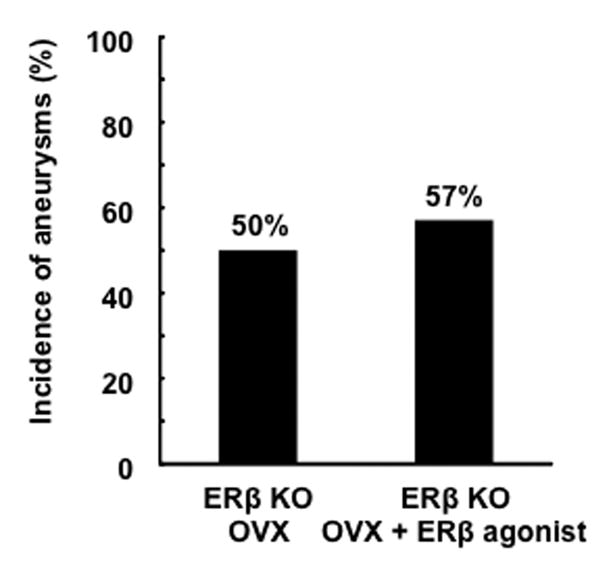

To further confirm the protective role of DPN is through estrogen receptor-β stimulation, ovariectomized estrogen receptor-β knockout mice were treated with DPN or vehicle. The protective effect of DPN treatment was abolished in estrogen receptor-β knockout mice (50% vs. 57%) (Figure 4), indicating that the protective effect of DPN was primarily attributed to its activation of estrogen receptor-β.

Figure 4. Effects of estrogen receptor-β agonist in ovariectomized estrogen receptor-β knockout mice.

Unlike in wild-type mice, estrogen receptor-β agonist did not affect the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized estrogen receptor-β knockout mice (ERβ KO). OVX: bilateral ovariectomy.

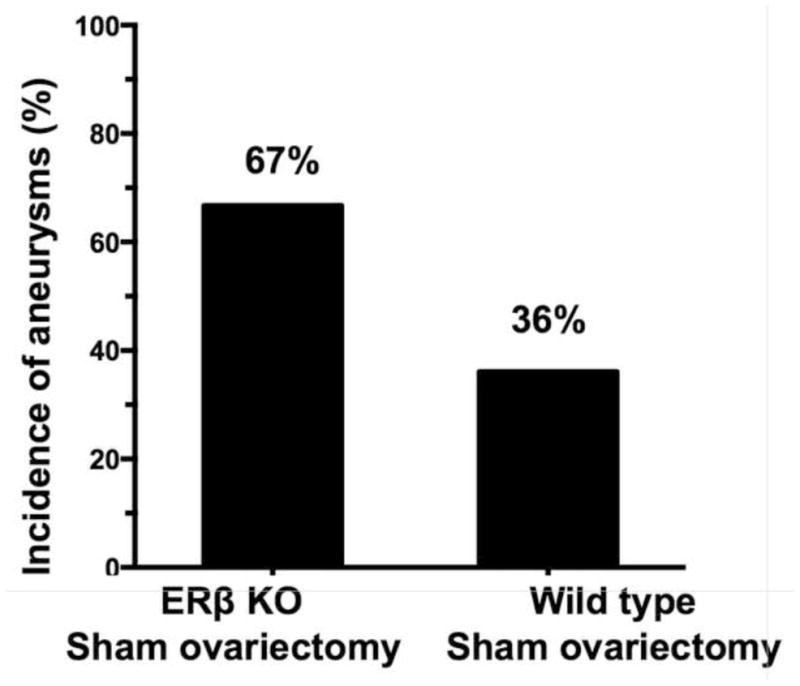

We further assessed the role of estrogen receptor-β by inducing intracranial aneurysms in estrogen receptor-β knockout mice with sham ovariectomy. There was a trend for the sham-ovariectomized estrogen receptor-β knockout mice to have higher incidence of aneurysms than wild-type mice with sham ovariectomy (67% vs. 36%, P = 0.10) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Formation of aneurysms in sham ovariectomized estrogen receptor-β knockout mice and wild-type mice.

The protective effect of estrogen receptor-β stimulation depends on nitric oxide production

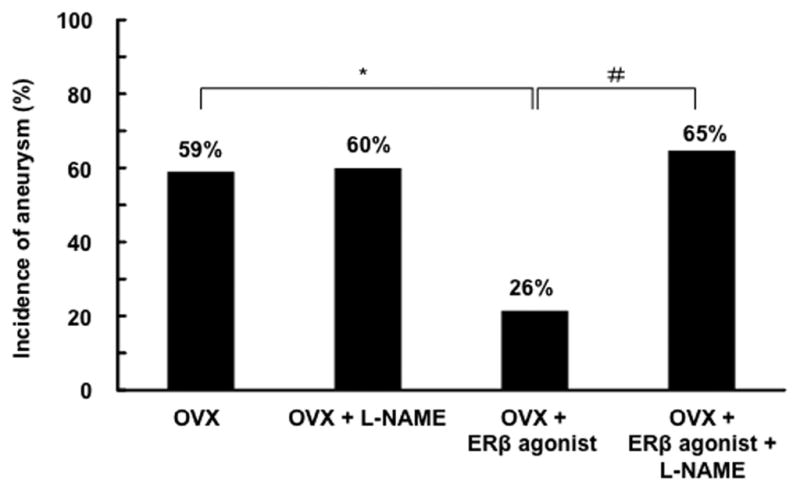

Estrogen can exert various effects on vasculature by increasing the production and availability of nitric oxide.12 Stimulation of estrogen receptor-β can up-regulate nitric oxide production, at least partially, through the s-nitrosylation of various target proteins.13, 14 Therefore, we tested whether the protective effect of estrogen receptor-β stimulation against aneurysm formation was dependent on the production of nitric oxide. We treated mice with a non-specific nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME). As shown in Figure 6, although L-NAME alone did not affect the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice, it abolished the protective effect of DPN (L-NAME + DPN vs. DPN alone = 65 % vs. 26%, respectively, P < .05), indicating that the protective effect of estrogen receptor-β stimulation against the formation of aneurysms depends on the production of nitric oxide by nitric synthase.

Figure 6. The protective effect of estrogen receptor-β agonist was abolished by the inhibition of nitric oxide synthase.

A nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), did not affect the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice. However, L-NAME abolished the protective effect of estrogen receptor-β agonist in ovariectomized mice (65 vs. 26%, P < .05). *: P < .05, **: P < .01 compared to OVX. #: P < 0.05 compared to OVX + ERβ. OVX: bilateral ovariectomy. ER: estrogen receptor

Discussion

In this study, we found that ovariectomized female mice had a higher incidence of aneurysms than male mice and that there was no difference in the incidence of aneurysms between non-ovariectomized female mice and male mice. These findings were generally consistent with human epidemiological studies revealing that the female preponderance of intracranial aneurysms becomes significant only after the fourth or fifth decades (in peri- and post-menopause).1, 2 The consistencies between the animal data and human epidemiological observations support the rationale for using this animal model to study potential mechanisms of the gender difference in the pathophysiology of intracranial aneurysms.

The estrogen receptor-β agonist significantly reduced the incidence of aneurysms in ovariectomized mice; however, the estrogen receptor-α agonist failed to reduce the incidence of aneurysms. The protective effect of estrogen receptor-β simulation was further supported by the lack of protective effect of estrogen receptor-β agonist in mice that lacked estrogen receptor-β. Estrogen receptor-α and estrogen receptor-β regulate different sets of genes and mediate different cellular and tissue effects.15 For example, in vascular smooth muscle cells, while estrogen receptor-β mediates the upregulation of an inducible form of nitric oxide synthase, estrogen receptor-α exerts the opposite effect.16 In cardiomyocytes, inducible nitric oxide synthase is involved in both acute and chronic inflammation; these processes are emerging as an integral part of the pathophysiology of intracranial aneurysms.17, 18 In our experiment, we found that the protective effect of estrogen receptor-β activation was dependent upon the production of nitric oxide. Similar to our findings, it has been reported that estrogen’s cardioprotective effects are mainly mediated by estrogen receptor-β in a nitric oxide-dependent manner.14, 19 Nitric oxide synthase is involved in acute and chronic inflammation, processes that are emerging as an integral part of the pathophysiology of intracranial aneurysms.17, 18, 20 The s-nitrosylation of various proteins by nitric oxide can prevent the oxidative modification of cysteine residues,14, 19 thereby potentially reducing the excessive tissue remodeling that leads to aneurysm formation.17

It should be noted that there are a number of factors that can potentially limit the translational potential of our findings. First, the animal models do not completely replicate biological events that lead to aneurysm formation and growth. Second, the surgical menopause may not faithfully mimic the hormonal changes that occur in women at the time of age-related menopause. Third, there may be differences in the effects of estrogen or estrogen-β agonist between humans and mice. Fourth, we have not completely identified the exact process that can be modulated by the estrogen receptor-β agonist.

Our findings were generally consistent with previous experimental studies that utilized a rat model of intracranial aneurysm.21–23 While aneurysms in our mouse model were induced by a combination of DOCA-salt hypertension and a single injection of elastase, the previous studies that used rats utilized a combination of unilateral carotid artery ligation, renal hypertension, and ovariectomy. The fact that these two different models yielded similar findings on the role of estrogen in the formation of aneurysms may indicate that these two models share similar or identical downstream processes that lead to aneurysm formation. Utilizing the mouse model, we were able to establish the role of estrogen receptor-β in the protection against the formation of aneurysms.

The female mice reach reproductive maturity at approximately 7 weeks, and menopause occurs at approximately 12–14 months. We used mice aged 8–12 weeks, an age range that has been used by the majority of studies that assessed roles of estrogen during the post-menopausal period.24, 25 Ovariectomy in pre-menopausal mice may not completely simulate physiological menopause.26 Ovariectomy may result in the abrupt loss of ovarian hormones and bypass the peri-menopausal stage, which can be characterized by a gradual loss and fluctuation of estrogen. Further studies using older female mice may be needed to confirm the protective effect of estrogen receptor-β activation against aneurysm formation in post-menopausal female mice.

Menopause causes a relative loss of estrogen and progesterone. Progesterone can improve outcomes after ischemic and traumatic brain injury in animals partly through modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress.27 There seem to be interactions between estrogen and progesterone in neuroprotection.27 In addition, testosterone can augment inflammation by modulating oxidative stress or activating pro-inflammatory cytokines.28 Vascular inflammation in the brain may be influenced by the balance among estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone.28 Thus, other sex steroids and their interactions should be studied in future studies. The gender difference in the incidence of aneurysms may be determined by the complex interactions and balance of sex steroids.

One of the limitations of this study is that we did not directly measure the blood estrogen levels. Instead, we measured the uterine weight to assess the stimulation of estrogen receptor, primarily estrogen receptor-α, as previously described.14, 29 Although DPN is highly selective for estrogen receptor-β, it still possesses a weak agonistic effect on estrogen receptor-α (estrogen receptor-α vs. estrogen receptor-β = 1:170).26 PPT, a selective estrogen receptor-α, also has a weak agonistic activity on estrogen receptor-β (estrogen receptor-α vs. estrogen receptor-β = 1000:1).30 Estrogen and PPT, but not DPN, significantly increased the uterine weight in the ovariectomized mice in a manner consistent with previous studies,14, 31 which indicated the specificity of DPN and the efficacy of estrogen and PPT in our experiments.

Estrogen’s unwanted effects, such as increased risks for breast cancer and endometrial cancer in certain populations, are often attributed to its agonistic activity without tissue specificity.32 To avoid the unwanted effects of estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) with tissue specificity are under vigorous investigation. SERMs are synthetic compounds that act as estrogen receptor agonists in some tissues and estrogen receptor antagonists in other tissues.33 Our finding of the superior protective effect of the selective estrogen receptor-β agonist compared to estrogen may become the basis for testing SERMs with a favorable tissue specificity profile for preventing the growth and rupture of intracranial aneurysms in humans, particularly in post-menopausal women.

Conclusion

The effects of gender, menopause, and estrogen treatment observed in this animal study were consistent with previous epidemiological findings. Stimulation of estrogen receptor-β may confer the protective effect against the formation of aneurysms in post-menopausal women.

Supplementary Material

All values are presented mean ± SD. OVX: bilateral ovariectomy; ER: estrogen receptor; L-NAME: N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (nitric oxidase synthase inhibitor); ERβKO: estrogen receptor-β knockout mice. All values are presented as mean ± SD.

Footnotes

Disclosure of funding: The project described was supported by R01NS055876 (TH.), R01NS082280 (TH), and K08NS082363 (DMH) from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS), American Heart Association Grant-in-aid 11GRNT6380003 (TH), and the Brain Aneurysm Foundation Shirley Dudek Demmer Chair of Research (TH, KS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS, NIH, the American Heart Association, and the Brain Aneurysm Foundation.

Financial support and industry affiliations: none

References

- 1.de Rooij NK, Linn FH, van der Plas JA, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;78(12):1365–1372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.117655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menghini VV, Brown RD, Jr, Sicks JD, O’Fallon WM, Wiebers DO. Incidence and prevalence of intracranial aneurysms and hemorrhage in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1965 to 1995. Neurology. 1998 Aug;51(2):405–411. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stober T, Sen S, Anstatt T, Freier G, Schimrigk K. Direct evidence of hypertension and the possible role of post-menopause oestrogen deficiency in the pathogenesis of berry aneurysms. J Neurol. 1985;232(2):67–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00313903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrod CG, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. Deficiencies in estrogen-mediated regulation of cerebrovascular homeostasis may contribute to an increased risk of cerebral aneurysm pathogenesis and rupture in menopausal and postmenopausal women. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66(4):736–756. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eden SV, Meurer WJ, Sanchez BN, et al. Gender and ethnic differences in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2008 Sep 2;71(10):731–735. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319690.82357.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. Molecular and cellular basis of cardiovascular gender differences. Science. 2005 Jun 10;308(5728):1583–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1112062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galea E, Santizo R, Feinstein DL, et al. Estrogen inhibits NF kappa B-dependent inflammation in brain endothelium without interfering with I kappa B degradation. Neuroreport. 2002 Aug 7;13(11):1469–1472. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200208070-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tada Y, Kanematsu Y, Kanematsu M, et al. A mouse model of intracranial aneurysm: technical considerations. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;111:31–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makino H, Tada Y, Wada K, et al. Pharmacological stabilization of intracranial aneurysms in mice: a feasibility study. Stroke. 2012 Sep;43(9):2450–2456. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanematsu Y, Kanematsu M, Kurihara C, et al. Critical roles of macrophages in the formation of intracranial aneurysm. Stroke. 2011 Jan;42(1):173–178. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.590976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuki Y, Tsou TL, Kurihara C, Kanematsu M, Kanematsu Y, Hashimoto T. Elastase-induced intracranial aneurysms in hypertensive mice. Hypertension. 2009 Dec;54(6):1337–1344. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess DT, Foster MW, Stamler JS. Assays for S-nitrosothiols and S-nitrosylated proteins and mechanistic insights into cardioprotection. Circulation. 2009 Jul 21;120(3):190–193. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuedling S, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor beta is a prerequisite for estrogen-dependent upregulation of nitric oxide synthases in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. FEBS Lett. 2001 Aug 3;502(3):103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J, Steenbergen C, Murphy E, Sun J. Estrogen receptor-beta activation results in S-nitrosylation of proteins involved in cardioprotection. Circulation. 2009 Jul 21;120(3):245–254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.868729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leitman DC, Paruthiyil S, Vivar OI, et al. Regulation of specific target genes and biological responses by estrogen receptor subtype agonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010 Dec;10(6):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsutsumi S, Zhang X, Takata K, et al. Differential regulation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene by estrogen receptors 1 and 2. J Endocrinol. 2008 Nov;199(2):267–273. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto T, Meng H, Young WL. Intracranial aneurysms: links between inflammation, hemodynamics and vascular remodeling. Neurol Res. 2006 Jun;28(4):372–380. doi: 10.1179/016164106X14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasan DM, Mahaney KB, Brown RD, Jr, et al. Aspirin as a promising agent for decreasing incidence of cerebral aneurysm rupture. Stroke. 2011 Nov;42(11):3156–3162. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.619411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J, Picht E, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Hypercontractile female hearts exhibit increased S-nitrosylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit and reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2006 Feb 17;98(3):403–411. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202707.79018.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tymianski M. Aspirin as a promising agent for decreasing incidence of cerebral aneurysm rupture. Stroke. 2011 Nov;42(11):3003–3004. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura T, Jamous MA, Kitazato KT, et al. Endothelial damage due to impaired nitric oxide bioavailability triggers cerebral aneurysm formation in female rats. J Hypertens. 2009 Jun;27(6):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328329d1a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamous MA, Nagahiro S, Kitazato KT, Tamura T, Kuwayama K, Satoh K. Role of estrogen deficiency in the formation and progression of cerebral aneurysms. Part II: experimental study of the effects of hormone replacement therapy in rats. J Neurosurg. 2005 Dec;103(6):1052–1057. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamous MA, Nagahiro S, Kitazato KT, Satomi J, Satoh K. Role of estrogen deficiency in the formation and progression of cerebral aneurysms. Part I: experimental study of the effect of oophorectomy in rats. J Neurosurg. 2005 Dec;103(6):1046–1051. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki S, Brown CM, Dela Cruz CD, Yang E, Bridwell DA, Wise PM. Timing of estrogen therapy after ovariectomy dictates the efficacy of its neuroprotective and antiinflammatory actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Apr 3;104(14):6013–6018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610394104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toutain CE, Filipe C, Billon A, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha expression in both endothelium and hematopoietic cells is required for the accelerative effect of estradiol on reendothelialization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 Oct;29(10):1543–1550. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.192849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. J Med Chem. 2001 Nov 22;44(24):4230–4251. doi: 10.1021/jm010254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng J, Hurn PD. Sex shapes experimental ischemic brain injury. Steroids. 2009 Nov 10; doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause DN, Duckles SP, Pelligrino DA. Influence of sex steroid hormones on cerebrovascular function. J Appl Physiol. 2006 Oct;101(4):1252–1261. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01095.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Divoux A, Sun J, et al. Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nat Med. 2009 Aug;15(8):940–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiwari-Woodruff S, Morales LB, Lee R, Voskuhl RR. Differential neuroprotective and antiinflammatory effects of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta ligand treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Sep 11;104(37):14813–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703783104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frasor J, Barnett DH, Danes JM, Hess R, Parlow AF, Katzenellenbogen BS. Response-specific and ligand dose-dependent modulation of estrogen receptor (ER) alpha activity by ERbeta in the uterus. Endocrinology. 2003 Jul;144(7):3159–3166. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendrix SL, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Johnson KC, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen on stroke in the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation. 2006 May 23;113(20):2425–2434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker C. Another selective estrogen-receptor modulator for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Feb 25;362(8):752–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0912847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All values are presented mean ± SD. OVX: bilateral ovariectomy; ER: estrogen receptor; L-NAME: N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (nitric oxidase synthase inhibitor); ERβKO: estrogen receptor-β knockout mice. All values are presented as mean ± SD.