Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine prevalence, intensity, and zoonotic potential of gastrointestinal parasites in free-roaming and pet cats in urban areas of Saskatchewan (SK) and a rural region in southwestern Alberta (AB). Fecal samples were analyzed using a modified double centrifugation sucrose flotation to detect helminth eggs and coccidian oocysts, and an immunofluorescence assay to detect Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Endoparasite prevalence was higher in samples from rural AB cats (41% of 27) and free-roaming SK cats (32% of 161) than client-owned SK cats (6% of 31). Parasites identified using morphological and molecular techniques included Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina, Baylisascaris-type eggs, Eucoleus aerophilus, Taenia taeniaeformis, Isospora spp., Cryptosporidium spp., and zoonotic genotype A of Giardia duodenalis. This study demonstrates significant differences in endoparasite prevalence in feline populations, and the value of molecular techniques in fecal-based surveys to identify and determine parasite zoonotic potential.

Résumé

Parasites entériques des chats errants, des chats avec propriétaire et des chats ruraux dans les régions des Prairies du Canada. Cette étude avait pour but de déterminer la prévalence, l’intensité et le potentiel zoonotique des parasites gastro-intestinaux chez les chats errants et les chats animaux de compagnie dans les régions urbaines de la Saskatchewan et une région rurale du Sud-Ouest de l’Alberta. Des échantillons de fèces ont été analysés à l’aide d’une méthode modifiée de flottaison au sucrose à double centrifugation afin de détecter les œufs d’helminthe et les ookystes coccidiens et une épreuve d’immunofluorescence a été réalisée pour détecter Giardia et Cryptosporidium. La prévalence des endoparasites était supérieure dans les échantillons provenant de chats ruraux de l’Alberta (41 % de 27) et de chats errants de la Saskatchewan (32 % de 161) que dans ceux de chats appartenant à des clients (6 % de 31). Les parasites identifiés à l’aide de techniques morphologiques et moléculaires incluaient Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina, des œufs de type Baylisascaris, Eucoleus aerophilus, Taenia taeniaeformis, Isospora spp., Cryptosporidium spp., et un génotype zoonotique A de Giardia duodenalis. Cette étude démontre les différences significatives dans la prévalence des endoparasites chez les populations félines et la valeur des techniques moléculaires dans les études basées sur les fèces afin d’identifier et de déterminer le potentiel zoonotique.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

The overall prevalence and intensity of gastrointestinal parasitism in cats in prairie regions of western Canada is thought to be low, especially in pet cats (1). There are a limited number of studies in this region to guide choice of veterinary diagnostic techniques and treatments (Table 1, 1–10). In part, this is because earlier studies of helminths in cats in Canada relied on recovery of adult parasites at postmortem to definitively identify parasite species (3,4,10), as species-level identification of stages shed in feces is not possible for many parasites. Advances in molecular identification have now made it possible to determine species and zoonotic potential of parasite stages shed in feces, rendering fecal surveys a much more powerful tool.

Table 1.

Prevalence (% samples or animals positive) of enteric helminth and protozoan parasites in cats in Canada in the current and previous studies (from west to east). In the current study, free-roaming includes shelter and feral cats in urban regions of Saskatchewan

| Province | Type (number) | Methoda | Toxocara | Toxascaris | Hookworm | Taeniids | Dipylidium | Coccidia | Giardia | Cryptosporidium | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | Rural (27) | SCF/IFA 27/27 | 15% | 4% | 0% | 22% | 0% | 19% | 11% | 0% | Current studyc |

| SK | Free-roaming (161) | SCF/IFA 161/148 | 1%b | 0% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 6% | 16% | 7% | |

| SK | Pet (31) | SCF/IFA 31/29 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 3% | 0% | |

| AB | Shelter (85) | ZCF | 11% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | < 1% | 0% | 0% | (1) |

| Pet (68) | ZCF | 2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| SK | Pet (644) | SCF/IFA | 5% | < 1% | < 1% | 1% | 0% | 4% | 10% | 2% | (2) |

| SK | Shelter (52) | PM | 17% | 0% | 2% | 15% | 2% | NT | NT | NT | (3)d |

| SK | Pet/Shelter (131) | PM | NT | NT | NT | 12% | NT | NT | NT | NT | (4)e |

| ON | Shelter (47) | SCF | 11% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 13% | 0% | 0% | (5)f |

| ON | Pet (8160) | NR | 2% | NT | NT | NT | NT | < 1% | < 1% | NT | (6) |

| Pet (41) | NNF/Mix | 12% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 7% | 10% | 2% | 7% | ||

| ON | Unstated (458) | NNF | 30% | 2% | 4% | 14% | 1% | 9% | NT | NT | (7)g |

| PEI | Feral (78) | ZCF | 31% | 0% | 0% | 15% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | (8)h |

| NS | Shelter (299) | NClF | 25% | < 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 0% | (9)i |

| NL | Unstated (35) | PM | 46%h | 3% | 0% | 0% | 9% | NT | NT | NT | (10)j |

Detection methods (in order of appearance): SCF — Sucrose Centrifugation-Flotation; IFA — Immunofluorescence Assay for Giardia and Cryptosporidium; ZCF — Zinc Sulphate Centrifugation-Flotation; PM — Postmortem; NT — not tested; NR — Not reported; NNF — Sodium Nitrate Flotation; Mix — Formalin-Ethyl Acetate Concentration and acid-fast staining/enzyme immunoassay for Cryptosporidium; NClF — Sodium Chloride Flotation on samples in 10% formalin.

One sample contained eggs and the other a single adult male of T. cati.

Also detected: Eucoleus aerophila and Baylisascaris spp.

Also detected: Ollulanus tricuspis and Physaloptera spp.

3 of 131 (2%) cats had Echinococcus multilocularis and 16 of 131 (12%) cats had Taenia spp.

Also detected: Aoncotheca spp., Eucoleus aerophila.

Also detected: Capillaria, Strongyloides, Aelurostrongylus, Diphyllobothrium, and Paragonimus spp.

Also detected: Toxoplasma gondii.

Also detected: Capillaria spp.

Also detected: Diphyllobothrium dentriticum.

There are a number of potentially zoonotic helminth parasites in cats in western Canada, including Toxocara cati, Ancylostoma tubaeforme, Echinococcus multilocularis, and Dipylidium caninum, as well as protozoan parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii, Giardia spp., and Cryptosporidium spp. (Table 1). While the prevalence and intensity of parasites might be expected to be higher in feral, shelter, rural, and free-roaming cats, pet cats which have closer contact with humans may pose a greater risk for zoonotic transmission. Therefore, determining the prevalence and intensity of endoparasites in all these cat populations is important.

The purpose of this study was to determine the diversity, prevalence, and zoonotic potential of helminth and protozoan parasites in free-roaming, client-owned, and rural cats in Saskatchewan (SK) and Alberta (AB) in order to guide recommendations for feline parasite treatment and control in western Canada.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and storage

Fecal samples were obtained from 31 client-owned cats through voluntary owner submissions in Saskatoon, SK, 161 free-roaming cats (shelter cats from Saskatoon and feral cats from Regina, SK), and 27 cats brought to a remote veterinary services clinic in a rural area in southwestern Alberta. Age, gender, health status, and previous parasite treatment history were not available for most of the free-roaming and shelter cats. For the shelter cats, there was little information on the source of the cats or the length of time that they had been in the shelter. Limited historical information was available on 21 of the 31 client-owned animals. Of these, 9 were strictly indoor, 4 were largely outdoor, and 8 had limited outdoor access (confined area under direct supervision or on leash). Of the client-owned cats, 15 were from multi-cat households and 7 represented multiple cats from the same household (2 pairs of cats and 1 set of 3 cats).

Fecal samples were stored in a freezer at −20°C for a maximum of 6 mo prior to diagnostic testing. As per the World Health Organization and World Organisation for Animal Health recommendations to protect human health (11), samples positive for taeniid eggs on fecal flotation were stored in a freezer at −80°C for a minimum of 5 d to inactivate eggs of Echinococcus multilocularis, a potentially zoonotic species that has been reported from cats in Saskatoon (4). The consistency of fecal sample submissions was classified on a scale from 1 (hard stool) to 7 (liquid stool) according to the Bristol Stool Chart (12) by a single observer prior to reading flotation slides. Scores for samples obtained from the Alberta population were not recorded. The study was approved by the Animal Research Ethics Board (AREB) at the University of Saskatchewan (Animal Use Protocol 20090043).

Fecal centrifugation-flotation and taeniid egg characterization

Helminth ova and coccidian oocysts were quantified using a modified Wisconsin double centrifugation sucrose flotation on a known quantity of feces (1 to 4 g) (13), and were identified to genus/family using light microscopy. In samples with high intensities, the total number of eggs/oocysts per gram of feces (EPG/OPG) was extrapolated from the proportion of the coverslip area containing 500 eggs/oocysts.

Taeniid eggs were recovered using a modified flotation- centrifugation technique and DNA was extracted from eggs using the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using primers (JB11 5′-AGA TTC GTA AGG GGC CTA ATA-3′ and JB12 5′-ACC ACT AAC TAA TTC ACT TTC-3′) targeting a 471 bp region of the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (NAD1) gene (14). Polymerase chain reaction was run according to the following sequence: initial denaturation (94°C for 3 min), 40 amplification cycles (94°C for 15 s, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s), and final extension (72°C for 1 min). Vector pGEM T Easy containing an NAD1 amplicon from Echinococcus granulosus was used as a positive control. Negative controls included a “no template control” and an extraction negative sample. The PCR products were purified using a Qiagen gel purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Saskatoon).

Giardia/Cryptosporidium immunofluorescent assay and Giardia genotyping

Analysis of feline feces to detect Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts and Giardia spp. cysts was only performed if sufficient sample remained following flotation [148 free-roaming (SK), 29 owned (SK), and all 27 rural (AB)]. Cysts and oocysts were isolated from a known quantity (0.5 to 2.0 g) of feces using a sucrose gradient centrifugation technique (15) followed by a commercial immunofluorescence assay (Giardi-a-Glo/Cyst-a-Glo, Waterborne, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA). Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts were counted on slides examined at 200× magnification under a fluorescence microscope and reported as cysts/oocysts per gram of feces. Concentrated cysts from Giardia positive submissions were retained and frozen at −20°C for molecular characterization. The DNA was extracted from cysts using the DNeasy Qiagen Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN), followed by a nested PCR using primers for a 511 bp segment of the beta-giardin gene (16). The PCR products were purified from ethidium-stained agarose gels using the Qiagen gel purification kit (QIAGEN). Purified genomic DNA from G. intestinalis ATCC3088 was used as a positive control. Negative controls included a “no template control” and an extraction negative sample. The DNA sequencing with secondary PCR primers was performed as described above, and sequences were compared with those in GenBank and our own sequence database to determine genotype.

Statistical analyses

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using logistic regression to identify associations between groups (independent variable) and the prevalence (dependent variable) of individual parasite genera (SPSS version 19, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The strength of association was reported as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A Wald test was used to determine if the association was statistically significant (P-value < 0.05). Data were also analyzed by ordinal regression to identify associations between fecal consistency (outcome) and risk factors (group, infection status).

Results

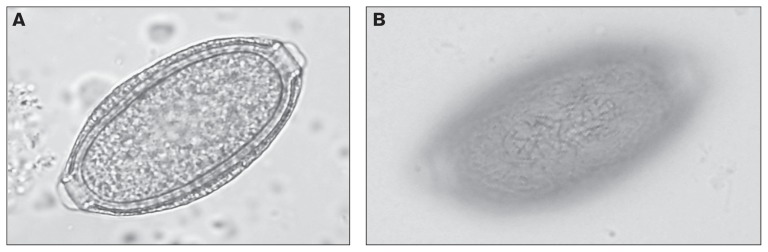

Overall, 41% of 27 samples from the cats in rural AB, 32% of 161 samples from free-roaming (shelter and feral) cats in SK, and 6% of 31 samples from client-owned urban cats in SK, were positive for at least 1 parasite. For rural cats in AB, the mean age was 1.1 y, range 0.2 to 3 y. Ascarid eggs most similar in appearance to those of Baylisascaris spp., and distinct from those of Toxocara and Toxascaris, were present in 1 sample from AB. One sample from SK contained eggs of Eucoleus aerophila (65 EPG), identified by the presence of anastomosing ridges on the shell (Figure 1) (17).

Figure 1.

A — Egg of Eucoleus aerophilus in feces from a cat in Saskatchewan; B — Image focused on the egg surface showing the characteristic network of branching and anastomosing ridges that distinguishes this from other capillarid species.

Prevalence (% samples positive) and intensity (median and range counts per gram of feces) of the most common parasites are reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Rural AB cats were more likely to be shedding eggs of T. cati [odds ratio (OR): 13.8, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.4 to 79.8); taeniid eggs (OR: 4.3, 95% CI: 1.4 to 13.1); and Isospora oocysts (OR: 3.8, 95% CI: 1.2 to 12.5) than were free-roaming cats in SK. There were no significant differences in parasite prevalence between free-roaming and owned cats in SK, nor among the 3 groups for Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected only in free-ranging cats in Saskatchewan.

Table 2.

Median intensity and range (eggs/cysts/oocysts per gram of feces) of the most common parasites present in fecal samples from cats in rural Alberta (AB) (n = 27), free-roaming (feral and shelter) cats (n = 161) in Saskatchewan (SK), and client-owned cats (n = 31) in SK in 2009

| Toxocara | Taeniid | Isospora | Giardiaa | Cryptosporidiuma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural, AB | 179 (3 to 330) | 23 (5 to 113) | 40 (20 to 60) | 1001 (200 to 80 707) | 0 |

| Free-roaming, SK | 28b | 48 (5 to 1040) | 98 (15 to 11 840) | 100 (3 to 166 750) | 300 (67 to 3635) |

| Client-owned, SK | 0 | 0 | 1485b | 133 400b | 0 |

Quantitative immunofluorescence assay on fecal samples from cats in rural AB (n = 27), free-roaming (feral and shelter) cats (n = 148) in SK, and client-owned cats in SK (n = 29).

Only one sample positive.

The median fecal consistency score for the samples evaluated (all from SK) was 4. Median fecal consistency for samples containing the following parasites was: Cryptosporidium, 3.5 (n = 10,) Giardia, 4.0 (n = 25), Isospora, 4.0 (n = 10), taeniid eggs, 5.0 (n = 10), and Toxocara, 6.0 (n = 2). Ordinal regression identified no statistically significant associations between fecal consistency score and group (free-roaming versus owned) or endoparasite infection. Similarly, when fecal consistency was converted into a dichotomous variable (0 = solid stool, 1 = loose stool), no significant effect was observed at the 5% level of confidence using logistic regression. Blood was visible in 2 samples positive for Isospora.

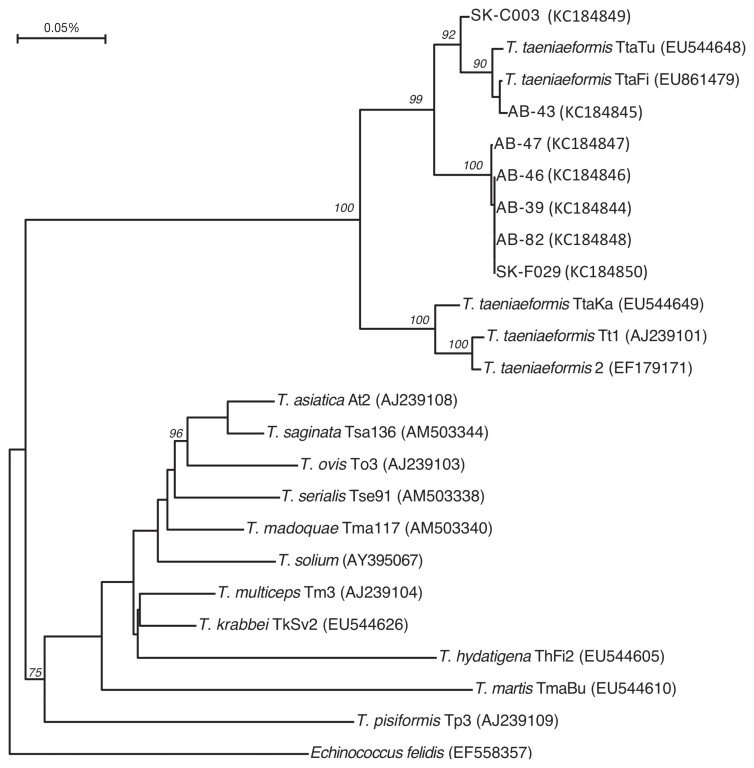

Of the 16 taeniid egg-positive samples, DNA sequence data was available for 7 (5 of 6 from AB and 2 of 10 from SK). From 373 to 488 bp of high quality sequence data were obtained for these 7 PCR products (GenBank accession numbers 184844 to 184850). Study sequences were aligned with published representative Taenia spp. NAD1 sequences and the alignment were trimmed to 352 bp prior to phylogenetic tree construction. All sequences clustered with Taenia taeniaeformis with good bootstrap support (Figure 2). High quality sequence data (440 bp) were available for 6 of 25 Giardia spp. positive samples from SK, and 2 of 3 from AB. These 8 sequences were 99% to 100% identical to each other and 99% to 100% identical to published sequences for G. duodenalis, zoonotic genotype A (GenBank Accession numbers 184851 to 184858).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on an alignment of a 352 bp region of the NAD1 mitochondrial gene from Taenia species, including 7 sequences derived from isolates from cats in the current study. The tree is a consensus of 100 bootstrap iterations of neighbor-joined trees created from distance matrices calculated using the F84 option in dnadist. The tree is rooted with Echinococcus felidis, and nodes with bootstrap values of > 50% are indicated. Province of origin of the study sequences is indicated by either SK (Saskatchewan) or AB (Alberta), and GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses.

Discussion

In 2009, the diversity of helminth parasite genera in fecal samples from cats in SK and AB was comparable to those reported in earlier studies in western Canada, including a retrospective study of samples from largely client-owned pet cats submitted to the Saskatchewan provincial diagnostic laboratory between 1998 and 2008 (2) (Table 1). In the current study, taeniid eggs (most likely Taenia taeniaeformis based on molecular characterization), coccidian oocysts (Isospora spp.), and Giardia cysts were the most common fecal parasites. In our study, fecal consistency did not appear to be a good predictor of parasite status. None of the protozoan and helminth parasites were associated with increased fecal consistency scores (i.e., soft stools) in samples from SK; however, blood was observed in 2 samples positive for Isospora, and not in any of the other samples. Clinical coccidiosis (including bloody diarrhea) is more common in young cats and can be severe under certain husbandry conditions.

The diversity, prevalence, and intensity of ascarids (Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina, and a Baylisascaris-type egg) were higher in rural cats from southwestern AB than in both free-roaming and owned cats in SK. The lower prevalence in SK cats may reflect deworming on admission to shelters and by owners; for many of these cats, we did not have complete treatment histories. This may also reflect the young age of cats sampled in AB, as younger cats are more likely to be shedding ascarid eggs (1,2). In general, ascarids do not seem to be highly prevalent in cat populations in western Canada (Table 1). Toxocara cati is a potential zoonotic parasite (18); however, human cases of toxocariasis appear to be rare in Canada, especially in northern regions (19). Baylisascaris-type eggs present in feces of 1 cat from rural Alberta may represent a true patent infection or spurious parasitism following ingestion of eggs in another infected host or host feces. Based on wildlife hosts present in this region, these are most likely B. columnaris of skunks (versus B. procyonis of racoons or B. transfuga of bears). Molecular identification would be useful in determining the specific identity of these eggs, which is important because of the zoonotic potential and pathogenicity of B. procyonis.

The presence of Eucoleus aerophilus (formerly Capillaria aerophilia) in a 1-year-old free-roaming male cat from SK was the first documented report of this parasite in cats in western Canada, although it has been reported in cats in Ontario (5). Infection is likely direct (acquired from consumption of eggs in soil, food, or water), and/or through consumption of earthworm intermediate hosts (17). For this cat, the parasite was likely acquired prior to admission (versus a shelter-acquired infection), since the cat was admitted 2 wks prior to sampling, and the pre-patent period of this parasite is 3 to 5 wk (20). Interestingly, this cat was shedding eggs despite treatment with pyrantel on admission 2 wk prior to sample collection. The cat had a clinical history of idiopathic anemia. In immunologically competent animals, most infections of E. aerophilus are asymptomatic (17); however, 8 of 11 cats positive for E. aerophilus had respiratory signs in an Italian study (21). In immunocompromised hosts, E. aerophilus is associated with respiratory signs, such as coughing and sneezing (22–24). It is possible that the true prevalence of Eucoleus is underestimated, due to morphological similarity of the eggs to those of Trichuris spp. and other capillarids (22). Eucoleus aerophilus is considered to have zoonotic potential and thus may be of both animal and public health significance (21).

In the present study, molecular techniques proved useful in determining zoonotic potential of parasites detected in a fecal survey. Taeniid eggs in feces of cats in SK and AB were non-zoonotic T. taeniaeformis, likely acquired by free-ranging cats through consumption of infected rodent intermediate hosts. Molecular techniques helped to differentiate these from morphologically identical eggs of Echinococcus multilocularis, although our techniques would likely have detected only the dominant species present in the sample. In addition, we were only able to obtain sequence data for 2 of the 10 taeniid-positive cats in SK. Echinococcus multilocularis is endemic to western Canada and has been found in cats in Saskatoon (4,19,25). Therefore, in the absence of routinely available molecular identification of parasites, veterinary practitioners in western Canada should treat all cats shedding taeniid eggs, and all cats with access to rodent intermediate hosts, with a cestocide, even though this study indicates that T. taeniaeformis is a more likely diagnosis than E. multilocularis.

For Giardia, molecular characterization suggests that the dominant species/genotype present in cats in western Canada is zoonotic genotype (A) G. duodenalis (Assemblage A). Similar results were reported from cats in a recent study in Ontario, Canada (26). Human infection is most commonly associated with G. duodenalis (Assemblage A) and G. enteritica (Assemblage B), while in cats, host-specific G. cati (Assemblage F) has been considered to be the most common species (27–31). Recent studies utilizing molecular methods have detected both G. cati (Assemblage F) and G. duodenalis (A-I and A-II) in cats (27,28,32–35). Although we detected only zoonotic G. duodenalis in this study, our techniques would have detected only the dominant strain, and not all samples amplified. Future work should include determination of the species and zoonotic potential of Cryptosporidium in cats in western Canada.

Infection with Giardia and Cryptosporidium may be more common in feline veterinary patients than currently perceived based on relatively insensitive fecal flotation methods (28) (Table 1). Using a sucrose gradient isolation followed by a commercial immunofluorescence assay (15), the prevalence of Giardia spp. in cats in the current study was 2.5 to 20× higher than that previously reported in Canadian cats (1,2,6). In rural cats, the median intensity of fecal shedding of Giardia cysts was 10× that of free-ranging urban cats (1000 versus 100 cysts per gram of feces — Table 2), which may reflect the young age of the rural cats, as well as increased access to contaminated food and water. One client-owned cat in SK had a high intensity of Giardia (over 100 000 cysts per gram of feces). This, in combination with molecular evidence that the most common genotype of Giardia in cats in the current study is zoonotic, suggests that cats with Giardia should be considered a source of environmental contamination with zoonotic genotypes.

Although this was a relatively small survey, subject to sampling bias and false negatives, fecal-based studies are increasingly useful when combined with DNA-based approaches to parasite identification (enhancing specificity and ability to determine zoonotic potential) and immunodiagnostic techniques such as fecal antigen detection for protozoan parasites (maximizing test sensitivity and specificity). Parasite prevalence was highest in rural, then free-roaming urban cats, and finally client-owned urban cats. Feeding commercial diets, increased frequency of anthelmintic treatments, and indoor-cat bylaws may account for the lower prevalence in client-owned urban cat populations. Relative to urban pets, feral, shelter, and rural cat populations in western Canada may be at higher risk for shedding infective stages of potentially zoonotic nematodes (Toxocara cati, E. aerophilus, and Baylisascaris) and protozoans (Giardia and Cryptosporidium). Therefore, these findings can help to guide appropriate diagnostic approaches and parasite control strategies for management of feline populations in western Canada from both public and animal health perspectives.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Catherine Vermette and Phillip Curry. CVJ

Footnotes

This work was funded through the Western College of Veterinary Medicine Interprovincial Summer Undergraduate Student Research Scholarship, new faculty funding from the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan Health Research Fund New Investigator Establishment and Equipment Grants, and a Canadian Foundation for Innovation Leaders Opportunity Fund grant for the Zoonotic Parasite Research Unit.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Joffe D, van Niekerk D, Gagne F, Gilleard J, Kutz S, Lobingier R. The prevalence of intestinal parasites in dogs and cats in Calgary, Alberta. Can Vet J. 2011;52:1323–1328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoopes JH, Polley L, Wagner B, Jenkins EJ. A retrospective investigation of feline gastrointestinal parasites in western Canada. Can Vet J. 2013;54:359–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomroy WE. A study of helminth parasites of cats from Saskatoon. Can Vet J. 1999;40:339–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wobeser G. The occurrence of Echinococcus multilocularis (Leukart, 1863) in cats near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Can Vet J. 1971;47:197–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blagburn BL, Schenker R, Gagne F, Drake J. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in companion animals in Ontario and Quebec, Canada, during the winter months. Vet Therapeut. 2008;9:169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla R, Giraldo P, Kraliz A, Finnigan M, Sanchez AL. Cryptosporidium spp. and other zoonotic enteric parasites in a sample of domestic dogs and cats in the Niagara region of Ontario. Can Vet J. 2006;47:1179–1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slocombe JO. Parasitisms in domesticated animals in Ontario. I. Ontario Veterinary College Records 1965–70. Can Vet J. 1973;14:36–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stojanovic V, Foley P. Infectious disease prevalence in a feral cat population on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Can Vet J. 2011;52:979–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malloy WF, Embil JA. Prevalence of Toxocara spp. and other parasites in dogs and cats in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Can J Comp Med. 1978;42:29–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Threlfall W. Further records of helminths from Newfoundland mammals. Can J Zool. 1969;47:197–201. doi: 10.1139/z69-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F-X, Pawlowski ZS. WHO/OIE manual of echinococcosis in humans and animals: A public health problem of global concern. Paris, France: World Organization for Animal Health and World Health Organization; 2001. p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scan J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DD, Todd AC. Survey of gastrointestinal parasitism in Wisconsin dairy cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1962;141:706–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowles J, McManus DP. NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene sequences compared for species and strains of the genus Echinococcus. Int J Parasitol. 1993;23:969–972. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(93)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson ME, Thorlakson CL, Deselliers L, Morck DW, McAllister TA. Giardia and Cryptosporidium in Canadian farm animals. Vet Parasitol. 1997;68:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalle M, Jiminez-Cardosa E, Cacciò SM, Pozio E. Genotyping of Giardia duodenalis from humans and dogs from Mexico using a β-giardin nested polymerase chain reaction. J Parasitol. 2005;91:203–205. doi: 10.1645/GE-293R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 8th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: WB Saunders; 2003. pp. 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher M. Toxocara cati: An underestimated zoonotic agent. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins EJ, Schurer JM, Gesy KM. Old problems on a new playing field: Helminth zoonoses transmitted among dogs, wildlife, and people in a changing northern climate. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182:54–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowman DD, Hendrix CM, Lindsay DS, Barr SC. Feline Clinical Parasitology. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univ Pr; 2002. pp. 338–339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traversa D, Di Cesare A, Milillo P, Iorio R, Otranto D. Infection by Eucoleus aerophilus in dogs and cats: Is another extra-intestinal parasitic nematode of pets emerging in Italy? Res Vet Sci. 2009;87:270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess H, Ruotsalo K, Peregrine AS, Hanselman B, Abrams-Ogg A. Eucoleus aerophilus respiratory infection in a dog with Addison’s disease. Can Vet J. 2008;49:389–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrs VR, Martin P, Nicoll RG, Beatty JA, Malik R. Pulmonary cryptococcosis and Capillaria aerophila infection in an FIV-positive cat. Aust Vet J. 2006;78:154–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb10581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster SF, Martin P, Allan GS, Barrs VR, Malik R. Lower respiratory tract infections in cats: 21 cases (1995–2000) J Feline Med Surg. 2004;6:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polley L. Visceral larva migrans and alveolar hydatid disease. Dangers real or imagined. Vet Clin North Am. 1978;8:353–378. doi: 10.1016/s0091-0279(78)50041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDowall RM, Peregrine AS, Leonard EK, et al. Evaluation of the zoonotic potential of Giardia duodenalis in fecal samples from dogs and cats in Ontario. Can Vet J. 2011;52:1329–1333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monis PT, Andrews RH, Mayrhofer G, Ey PL. Genetic diversity within the morphological species Giardia intestinalis and its relationship to host origin. Infect Genet Evol. 2003;3:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fayer R, Santín M, Trout JM, Dubey JP. Detection of Cryptosporidium felis and Giardia duodenalis Assemblage F in a cat colony. Vet Parasitol. 2006;140:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao L, Fayer R. Molecular characterization of species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium and Giardia and assessment of zoonotic transmission. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:1239–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson RC, Palmer CS, O’Handley R. The public health and clinical significance of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in domestic animals. Vet J. 2008;177:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballweber LR, Xiao LH, Bowman DD, Kahn G, Cama VA. Giardiasis in dogs and cats: Update on epidemiology and public health significance. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalle M, Pozio E, Capelli G, Bruschi F, Crotti D, Cacciò SM. Genetic heterogeneity at the beta-giardin locus among human and animal isolates of Giardia duodenalis and identification of potentially zoonotic genotypes. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer CS, Traub RJ, Robertson ID, Devlin G, Reese R, Thompson RC. Determining the zoonotic significance of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in Australian dogs and cats. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papini R, Cardini G, Paoletti B, Giangaspero A. Detection of Giardia Assemblage A in cats in Florence, Italy. Parasitol Res. 2010;100:653–656. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasilopulous RJ, Rickard LG, Mackin AJ, Pharr GT, Huston CL. Genotypic analysis of Giardia duodenalis in domestic cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:352–355. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2007)21[352:gaogdi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]