Abstract

Background/Aims

Hemoadsorption may improve outcomes for sepsis by removing circulating cytokines. We tested a new sorbent used for hemoadsorption.

Methods

CTR sorbent beads were filled into columns of three sizes: CTR0.5 (0.5ml), CTR1 (1.0ml) and CTR2 (2.0ml) and tested using IL-6 capture in vitro. Next, rats were subjected to cecal ligation and puncture and randomly assigned to hemoadsorption with CTR0.5, CTR1 CTR2 or sham treatment. Plasma biomarkers were measured.

Results

In vitro, IL-6 removal was accelerated with increasing bead mass. In vivo, TNF, IL-6, IL-10, high mobility group box1, and cystatin C were significantly lower 24 hrs after CTR2 treatment. Seven-day survival rate was 50%, 64%, 63%, and 73% for the sham, CTR0.5, CTR1, CTR2 respectively.

Conclusion

CTR appeared to have a favorable effect on kidney function despite no immediate effects on cytokine removal. However, CTR2 beads did result in a late decrease of cytokines.

Keywords: Sepsis, cytokines, interleukin-6, hemoadsorption, necrosis factor, sorbents, acute kidney injury

Introduction

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory syndrome caused by infection, which is characterized by the production of inflammatory cytokines in the bloodstream and tissues. These cytokines have been implicated as important factors in the pathophysiology of sepsis and development of multiple organ failure [1-4]. However, numerous randomized trials testing individual anti-cytokine therapies for severe sepsis and/or septic shock have failed [5,6]. A large observational study of community-acquired sepsis secondary to pneumonia demonstrated that the mortality was correlated with high levels of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [7]. Thus, broad-spectrum removal of cytokines is a potential approach for the treatment of sepsis.

Blood purification techniques, especially hemoadsorption, remove cytokines and other inflammatory mediators from the blood, providing a possible treatment for severe sepsis [5,6]. We have previously shown that hemoadsorption using a novel polymer (CytoSorb) in experimental endotoxemia, cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) and bacterial clot implantation-induced sepsis in rats, could remove cytokines and improve short-term survival [8-12]. However, we also observed a delayed effect (24 hours or more after treatment) as well as protection against organ injury especially in the kidney and liver [11]. It is not known whether the results obtained are unique to CytoSorb or represent a “class-effect”. Many other adsorptive materials have been designed to remove inflammatory cytokines [13,14] and may also work to remove other injurious molecules. One such material is CTR, a sorbent, composed of porous cellulose beads to which a hydrophobic organic compound with a hexadecyl alkyl chain has been covalently bound to the surface (Kaneka Corp., Osaka, Japan). CTR was specifically developed to adsorb cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-6.

Thus, our objectives for this study were threefold; first to test for cytokine removal (in vitro) and effect on circulating cytokines (in vivo) early (4 hours) and late (24 and 48 hours) using CTR in an experimental model (CLP) of sepsis in the rat. Second, we sought to determine if CTR could protect against sepsis-induced renal and hepatic injury using cystatin C, creatinine and Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and effect circulating high-mobility group box (HMGB)-1 protein. Third we evaluated three “doses” of CTR to determine if there was a dose-response relationship for these observed effects. Finally, although we did not power our study for survival but we did examine mortality at one-week across the various groups.

Materials and methods

All animal experiments were approved and conducted according to an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh and in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sorbent columns were manufactured in three sizes 0.5, 1 and 2 ml denoted here as CTR0.5, CTR1, and CTR2. These columns were filled with 0.75g, 1.6g, and 3.0g of sorbent respectively. Column components were EtOH sterilized and filled with sterile CTR sorbent beads using manufacture's recommendations.

In Vitro study

CTR sorbent beads (Lot BAP005-A0084) were characterized by spiking recombinant human cytokine into 8mL horse serum, and recirculating the solution through a packed bead column. Each column size was tested using IL-6 capture as a marker for manufacturing repeatability. The CTR1 columns were also characterized for TNF capture. Cytokine capture trials were run in triplicate, and identical cytokine and serum lots (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) were used for all experiments. Packed columns were primed with 10mM PBS, and capture was performed at a flow rate of 0.8mL/min using a peristaltic pump. Samples were removed from the reservoir at specific time points, immediately frozen at −80°C, and quantified for cytokine concentration using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Invitrogen ELISA kits). Samples were collected prior to capture (t=0) and then at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240min. ELISA analysis was performed in duplicate for each sample.

In Vivo study

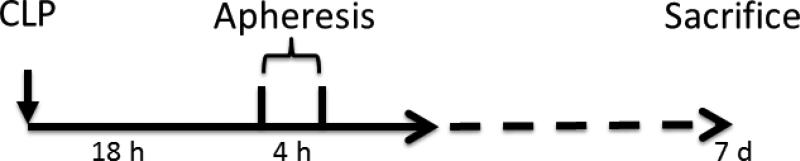

After the validating the fabrication of consistent CTR devices at the bench, we performed a series of animal studies using our standard LD-50 CLP model of sepsis in rats to compare CTR hemoadsorption to a sham treatment. This work was based on evaluating the three size devices versus a sham device (no CTR) in 40 adult (24 to 28 weeks old, weight 450-550g), male, Sprague-Dawley rats(Fig 1). Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and polymicrobial sepsis was induced with CLP, which was performed with a predetermined 25% ligated length of cecum and 20-gauge needle, with the two-punctures inferior to the ileocecal valve. The abdomen was then closed and 20 ml/kg lactated ringers were given subcutaneously as fluid resuscitation. Topical anesthetic was applied to the surgical wound. Rats were then returned back to their cages and allowed food and water ad libitum.

Fig. 1.

Experiment scheme flow chart in vivo

Eighteen hours after CLP, the animals were reanesthetized with isoflurane. The femoral vein and the internal jugular vein were isolated by dissection and cannulated with 1.27 mm polyethylene-90 tubing for use with extracorporeal circulation [15]. Animals were randomly assigned to receive treatment with either CTR 0.5, CTR 1 or CTR 2 or sham treatment for four hours. The extracorporeal circulation was driven by a mini pump (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at a blood flow rate of 0.8-1.0ml/min from the internal jugular vein to the femoral vein. In the CTR groups, the blood flowing through the extracorporeal circuit passed through the cartridges containing the adsorptive beads (dead space 0.5ml). In the sham group, the blood passed through the extracorporeal circuit in additional tubing with the same volume of dead space as the column. All of the tubing in the extracorporeal circuit was primed with heparinized saline (20units/ml) before beginning the experiment. After a four hour intervention, the treatments were stopped and the rats were observed for recovery. Survival time was assessed up to seven days.

Blood (0.8ml) was drawn from the femoral line at 18 hrs after CLP (immediately before treatment), at 0 hrs, after the 4 hr treatment, and then at 24 hrs and 48 hrs after treatments. The maximum blood loss for each animal was less than 20% total blood volume. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation, and stored in a −80°C degree freezer. Plasma cytokines (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10) were measured with Multiplex Bead Immunoassays. HMGB-1 and cystatin C were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. ALT was determined using a LDH-NADH coupled assay, and creatinine was measured with a creatinine enzymatic assay kit. Survival time was recorded in days starting from CLP.

Statistical analysis

The percentage changes compared to the baseline values (t=0) for cytokines (IL-6 and TNF) were expressed in the in-vitro study. All cytokine data from the in-vivo study (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10) were natural log (ln) transformed and expressed as mean ± standard error. Other non-normal distributive numeric data were expressed as median (range). Our primary analysis between CTR and sham-treated animals was based on changes in IL-6. All numeric data were compared by examining the mean differences among and within groups, and by analysis of variance for repeated measures (SPSS11, Chicago, IL). P<0.05 was considered to be of significant difference.

Results

In vitro study

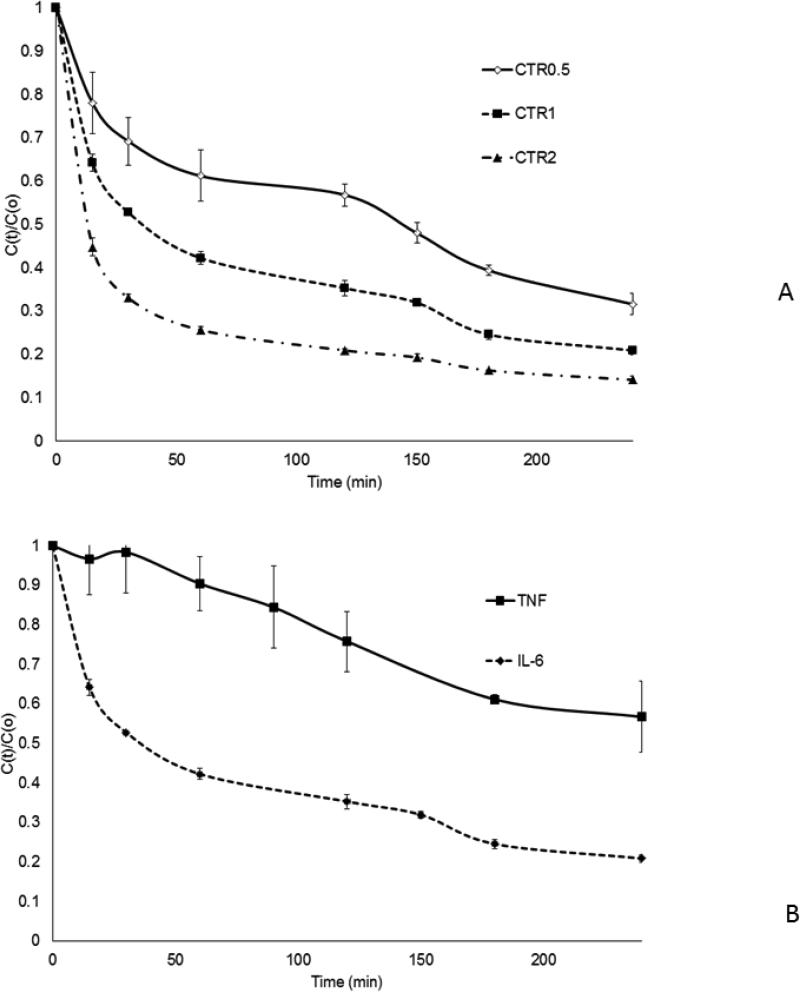

Mean normalized IL-6 removal rates for each size device are shown in Fig. 2A. The results demonstrate accelerated removal rates with increased bead mass. Mean normalized cytokine removal rates within the CTR1 device are illustrated for TNF and IL-6 (Fig. 2B), TNF capture rate is slower and more variable than that of IL-6.

Fig. 2.

In vitro cytokine removal with CTR beads (mean and SE).

C(t): concentrations at time t.

C(0):concentrations at baseline (time 0).

C(t)/C(0) reflecting cytokine capture rates.

CTR0.5: column filled with 0.5ml (0.75g) of sorbent beads

CTR1: column filled with 1 ml (1.6g) of sorbent beads

CTR2: column filled with 2ml (3 g) of sorbent beads Sham: the same size of extracorporeal circuit without sorbent

A.IL-6 capture rates for the different sized devices

B. TNF and IL-6 capture in horse serum for CTR1 columns

In vivo study

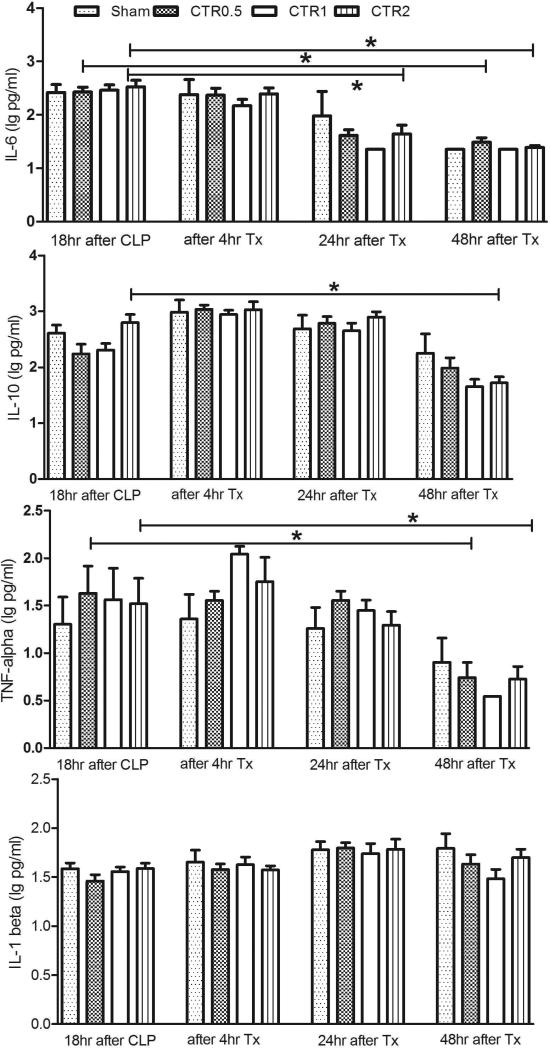

Differences in circulating plasma cytokine concentrations (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10) for septic rats treated with different amounts of CTR and sham are shown in Fig. 3. Baseline values (18 hrs after CLP) show no difference between the four groups for any cytokine. Plasma cytokine concentrations remained constant immediately after treatment and were not different among groups. At the later time points of 24 hrs and 48 hrs after treatment, the cytokine concentrations (IL-6, IL-10 and TNF) were significantly lower in the CTR treatment groups, especially CTR2, p<0.05 compared to baseline.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different sized CADs on cytokines (data are log transformed, and expressed as mean and SE).

CTR0.5: column filled with 0.5ml (0.75g) of sorbent beads

CTR1: column filled with 1 ml (1.6g) of sorbent beads

CTR2: column filled with 2ml (3 g) of sorbent beads

Sham: the same size of extracorporeal circuit without sorbent

Tx:treatment with hemoperfusion

*p<0.05, compared with baseline values in the same group

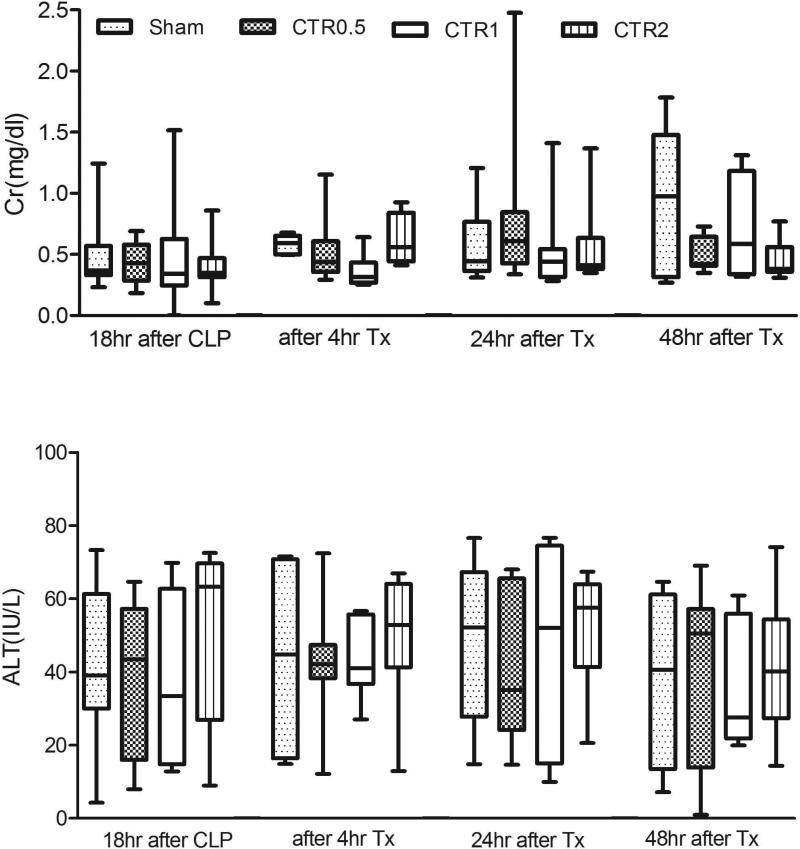

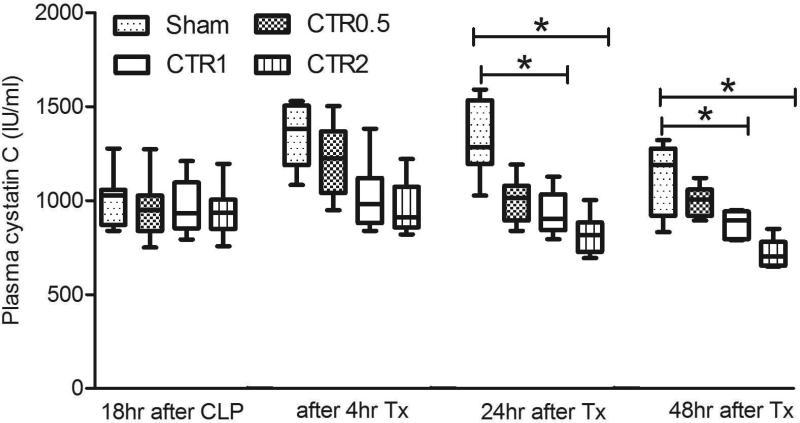

Fig. 4a demonstrates the effects of CTR on ALT and creatinine. Although there was a trend to improve ALT and creatinine, none of the differences reached statistical significance. However, Fig. 4b shows that cystatin C was significantly lower with CTR1 and CTR2 after 24 hrs (p<0.05). Furthermore, the overall trend in cystatin C suggests a dose-response relationship.

Fig. 4.

Effects of different sized CTR columns on plasma creatinine (Cr) and ALT (Panel A) (data are expressed as median and ranges), and on plasma cystatin C (Panel B) (data are expressed as median and ranges).

CTR0.5: column filled with 0.5ml (0.75g) of sorbent beads

CTR1: column filled with 1 ml (1.6g) of sorbent beads

CTR2: column filled with 2ml (3 g) of sorbent beads

Sham: the same size of extracorporeal circuit without sorbent

Tx: treatment with hemoperfusion

*p<0.05, compared with different group at the same time point

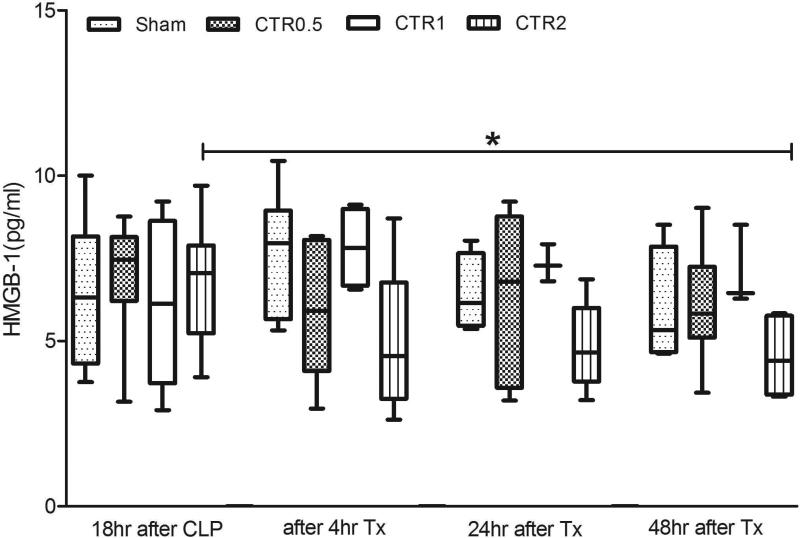

Fig. 5 shows the effects of different treatments on HMGB-1. There were no significant differences before treatments. However, after two days CTR2 showed a significant decrease compared to baseline (before treatment, p<0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effects of different sized CTR columns on HMGB-1 (data are expressed as median and ranges).

CTR0.5: column filled with 0.5ml (0.75g) of sorbent beads

CTR1: column filled with 1 ml (1.6g) of sorbent beads

CTR2: column filled with 2ml (3 g) of sorbent beads

Sham: the same size of extracorporeal circuit without sorbent

Tx: treatment with hemoperfusion

*p<0.05, compared with baseline values in the same group

Given the small overall sample size, survival was not formally compared. However, 5 of the 10 animals (50%) in the sham group survived for seven days, while survival rates in the treatment groups were 64% (7/11) with CTR0.5; 63% (5/8) with CTR1, and 73% (8/11) with CTR2.

Discussion

Our in vitro results clearly show that CTR was effective for IL-6 removal, and somewhat less effective for TNF removal. In vivo, CTR, especially the CTR2 device, appeared to have the same effect observed with other sorbents [9] on late (24-48 hour) concentrations of circulating IL-6, IL-10, TNF and HMGB-1 despite no immediate (4 hour) effects on cytokine concentrations. CTR1 and CTR2 devices also significantly reduced cystatin C at 24 & 48 hrs after treatment. Our results are in general agreement with those seen in our other studies [8-12] and suggest a class effect for sorbents. A dose-response relationship is also clearly evident (for IL-6) in vitro; and similar trends are seen in vivo.

While sufficient sized trials are lacking, in a recent meta-analysis, blood purification techniques including hemoperfusion, plasma exchange, and hemofiltration were associated with lower mortality in patients with sepsis [16]. However, standard renal replacement therapy is ineffective for modulating inflammatory mediators [17], despite a strong association between these mediators and survival [17]. Similarly, a recent multicenter trial by Joannes-Boyau found that high-volume hemofiltration (70 mL/kg/h) was no more effective than standard continuous hemofiltration (35 mL/kg/h) for patients with severe septic shock in terms of 28-day mortality, or organ function [18]. A meta-analysis of high-volume hemofiltration reached similar conclusions [19]. However, few trials measured cytokines and none measured pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or DAMPs). Our studies in animals clearly show that cytokine modulation can occur late [9,11] and organ protection may be achieved despite only minimal effect on circulating mediators [9,11]. HMGB-1, a well characterized DAMP, was also affected, but again the effect appeared late. These findings have not yet been integrated into the design of clinical trials but the consistency of the results across multiple studies, and now, across different sorbents, suggests that they need to be.

Designing devices and methods for sepsis therapy may require optimization of both filtration and adsorption. In an experiment to compare the relative effects of sieving and adsorption on plasma IL-6 following CLP in rats [20], we found that hemoadsorption was the main mechanism of removal. Hemoadsorption is dependent on membrane material and, during hemofiltration, on filtration operating parameters (e.g. filtration fraction: the so-called adsorption/synergistic effect). If hemofiltration is to be an effective therapy in the complexity of sepsis, then proper design of materials and operational characteristics must be pursued.

Using in vitro IL-6 capture, we have demonstrated very consistent results using various size devices. As expected, IL-6 removal is accelerated with increasing sorbent bead mass. TNF capture is slower than IL-6 capture, likely due to the large size of the trimeric TNF molecule (51kD) compared to IL-6 (26kD). In our CLP sepsis model, which closely resembles clinical sepsis, there appears to be a “dose-response relationship” on cytokines and on renal function (cystatin C). These results suggest that careful attention to sorbent volume in clinical devices may also be important.

We measured a panel of common cytokines in sepsis, TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10, as well as the late mediator HMGB-1. Plasma cytokine concentrations remained constant immediately after treatment and were not different among groups. However, by 24-48 hours after intervention, concentrations were significantly lower in the CTR-treated groups. At the same time there was strong evidence for renal protection measured by cystatin C. Although there was already a trend toward lower Cystatin C at 4 hours, it was not significant and the emergence of significant effects at 24 hours with persistence to 48 hours suggests improved renal function rather than Cystatin C clearance from the device. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of some removal of Cystatin C early on and we also note that the effects on serum creatinine were not significant. The possible explanation for this delayed cytokine removal and organ protections is the immunomodulation threshold hypothesis, which takes a more dynamic view, postulating that the cytokine removal from the blood compartment leads to the removal of cytokines located at the tissue level because of an equilibration of their concentrations between these two compartments [21,22]. This theory is interesting because it affects cytokines at the tissue level, which is where cytokines are harmful, and it also explains why numerous studies assessing blood purification techniques found an improvement of outcomes with no modification of cytokine blood concentrations as cytokines from the tissues replace those removed from the blood. Blood purification therapies might directly act at the inflammatory cell level in order to restore the immune function through the regulation of monocytes and neutrophils [7, 23].

Although this in vivo experiment more closely resembles human sepsis, there are important limitations. First, we did not administer antibiotics to the animals in this study because these therapies alter the inflammatory response and may well have obscured any “signal”. In addition, the administration of bactericidal antibiotics such as β-lactam drugs may promote the release of LPS from Gram-negative bacteria. Secondly, the sample size is too small to detect the potential differences in survival. However, this report could provide preliminary data for design of future large-scale studies.

Conclusion

CTR removes IL-6 in a dose-dependent fashion and appeared to result in lower cytokine levels and less kidney dysfunction also in a dose-dependent fashion. The favorable effect on renal function were evident despite no immediate effects on cytokine removal. However, CTR did result in a late decrease in multiple cytokines and HMGB-1. These results are consistent with other studies and suggest a “class-effect” for sorbents.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This work was funded in part by NIH R01DK070910 (JK and ZP) and Kaneka (WF and JK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Bone RC. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:457–467. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobi J. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(Suppl 1):53–58. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.suppl_1.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng ZY, Wang HZ, Srisawat N, Wen X, Rimmelé T, Bishop J, Singbartl K, Murugan R, Kellum JA. Bactericidal antibiotics temporarily increase inflammation and worsen acute kidney injury in experimental sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):538–543. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822f0d2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou FH, Peng ZY, Bishop JV, Cove ME, Singbartl K, Kellum JA. Effects of Fluid Resuscitation With 0.9% Saline Versus a Balanced Electrolyte Solution on Acute Kidney Injury in a Rat Model of Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):e270–e278. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimmelé T, Kellum JA. Clinical review: Blood purification for sepsis. Crit Care. 2011;15:205–215. doi: 10.1186/cc9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng ZY, Singbartl K, Simon P, Rimmelé T, Bishop J, Clermont G, Kellum JA. Blood purification in sepsis: a new paradigm. Contrib Nephrol. 2010;165:322–328. doi: 10.1159/000313773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the GenIMS study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(15):1655–1663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellum JA, Song M, Venkataraman R. Hemoadsorption removes tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10, reduces nuclear factor-kappa B DNA binding, and improves short-term survival in lethal endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:801–905. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114997.39857.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng ZY, Bishop JV, Wen XY, Elder MM, Zhou F, Chuasuwan A, Carter MJ, Devlin JE, Kaynar AM, Singbartl K, Pike F, Parker RS, Clermont G, Federspiel WJ, Kellum JA. Modulation of chemokine gradients by apheresis redirects leukocyte trafficking to different compartments during sepsis, studies in a rat model. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):R141. doi: 10.1186/cc13969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng ZY, Carter MJ, Kellum JA. Effects of hemoadsorption on cytokine removal and short-term survival in septic rats. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1573–1577. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318170b9a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng ZY, Wang HZ, Carter MJ, Dileo MV, Bishop JV, Zhou FH, Wen XY, Rimmelé T, Singbartl K, Federspiel WJ, Clermont G, Kellum JA. Acute removal of common sepsis mediators does not explain the effects of extracorporeal blood purification in experimental sepsis. Kidney Int. 2012;81(4):363–369. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Namas RA, Namas R, Lagoa C, Barclay D, Mi Q, Zamora R, Peng Z, Wen X, Fedorchak MV, Valenti IE, Federspiel WJ, Kellum JA, Vodovotz Y. Hemoadsorption reprograms inflammation in experimental gram-negative septic peritonitis: insights from in vivo and in silico studies. Mol Med. 2012;18:1366. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perego AF. Adsorption Techniques: Dialysis Sorbents and Membranes. Blood Purif. 2013;35(suppl 2):48–51. doi: 10.1159/000350848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taniguchi T, Hirai F, Takemoto Y, Tsuda K, Yamamoto K, Inaba H, Sakurai H, Furuyoshi S, Tani N. A novel adsorbent of circulating bacterial toxins and cytokines: the effect of direct hemoperfusion with CTR column for the treatment of experimental endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):800–806. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000202449.15027.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng ZY, Zhang J, Rimmelé T, Zhou F, Chuasuwan A, Kaynar AM, Kellum JA. Development of venovenous extracorporeal blood purification circuits in rodents for sepsis. J Surg Res. 2013;185(2):790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F, Peng Z, Murugan R, Kellum JA. Blood purification and mortality in sepsis: a meta-analysis randomized trials. Crri Care Med. 2013;41:2209–2220. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murugan R, Wen X, Shah N, Lee M, Kong L, Pike F, Keener C, Unruh M, Finkel K, Vijayan A, Palevsky PM, Paganini E, Carter M, Elder M, Kellum JA. Plasma inflammatory and apoptosis markers are associated with dialysis dependence and death among critically ill patients receiving renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;0:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joannes-Boyau O, Honoré PM, Perez P, Bagshaw SM, Grand H, Canivet JL, Dewitte A, Flamens C, Pujol W, Grandoulier AS, Fleureau C, Jacobs R, Broux C, Floch H, Branchard O, Franck S, Rozé H, Collin V, Boer W, Calderon J, Gauche B, Spapen HD, Janvier G, Ouattara A. High-volume versus standard-volume haemofiltration for septic shock patients with acute kidney injury (IVOIRE study): a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(9):1535–46. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2967-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark E, Molnar AO, Joannes-Boyau O, Honoré PM, Sikora L, Bagshaw SM1. High-volume hemofiltration for septic acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2014;818(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/cc13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellum JA, Dishart MK. Effects of hemofiltration on circulating IL-6 levels in septic rats. Crit Care. 2002;6:429–433. doi: 10.1186/cc1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honoré PM, Joannes-Boyau O. High volume hemofiltration(HVHF) in sepsis: A comprehensive review of rationale, clinical applicability, potential indications and recommendations for future research. Int J Artif Organs. 2004;27:1077–1082. doi: 10.1177/039139880402701211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honoré PM, Matson JR. Extracorporeal removal for sepsis: Acting at the tissue level-the beginning of a new era for this treatment modality in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:896–897. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000115262.31804.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimmelé T, Kaynar AM, McLaughlin JN, Bishop JV, Fedorchak MV, Chuasuwan A, Peng Z, Singbartl K, Frederick DR, Zhu L, Carter M, Federspiel MJ, Zeevi A, Kellum JA. Leukocyte capture and modulation of cell-mediated immunity during human sepsis: an ex vivo study. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):R59. doi: 10.1186/cc12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]