Abstract

We present a primary example of a cell-surface modified with a synergistic combination of agonists to tune immune stimulation. A model cell-line, Lewis Lung Carcinoma, was covalently modified with CpG-oligonucleotides and lipoteichoic acid, both Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists. The immune-stimulating constructs provided greater stimulation of NF-κB in a model cell line and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells than the components unconjugated in solution.

Immunotherapy is a promising treatment method that uses stimulation of receptors of the innate immune system to combat disease.1 Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are stimulated via molecular signals. These molecular signals, or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), can vary from oligonucleotides to bacterial cell wall components.2 Many current cell-based immunotherapies are comprised of one type of PAMP that stimulates only one PRR, resulting in a partial immune response. In contrast, effective vaccines, such as the yellow fever vaccine,3 are comprised of several signals that interact with multiple PRRs to elicit a robust immune response.4 Targeting antigens with molecular agonists is an important aspect in effective vaccines.1k,5 The chemical identity of a stimulating signal and its proximity to target antigens work in concert to elicit a specific immune response. Lipid anchoring6 and physical entrapment7 of molecular signals on tumor cells enhance immune response, but to date, the covalent attachment of multiple, synergistic agonist combinations on cell surfaces has not been attempted.

Here, we report the use of a polymeric linker to covalently modify Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) with lipoteichoic acid (LTA – TLR2/6 agonist)8 and CpG-oligonucleotides (CpG-ODN1826 – TLR9 agonist).9 We sought to answer the following questions. (1) Would direct, chemical modification of cell surface proteins enhance stimulation? and (2) Would synergistic combinations enabled by modular chemistry create increased activation or potential immune direction? We report that the PAMP-labeled cells upregulated cell surface marker expression, critical for T-cell activation. The multiple PAMP-labeled constructs also modulated cytokine production, allowing for the potential to design targeted vaccines. We also observed the macrophagocytosis of our PAMP-labeled cells, indicating a potential mechanism by which the immune-stimulating constructs are presented to an endosomal TLR9. The covalent attachment of LTA and CpG-ODN to cell surface proteins on tumor cells enhanced dendritic cell activation toward the modified tumor cells. Our approach demonstrates the significance of chemically conjugating PAMPs to target cell antigens as well as the use of multiple PAMPs in developing more effective vaccines.

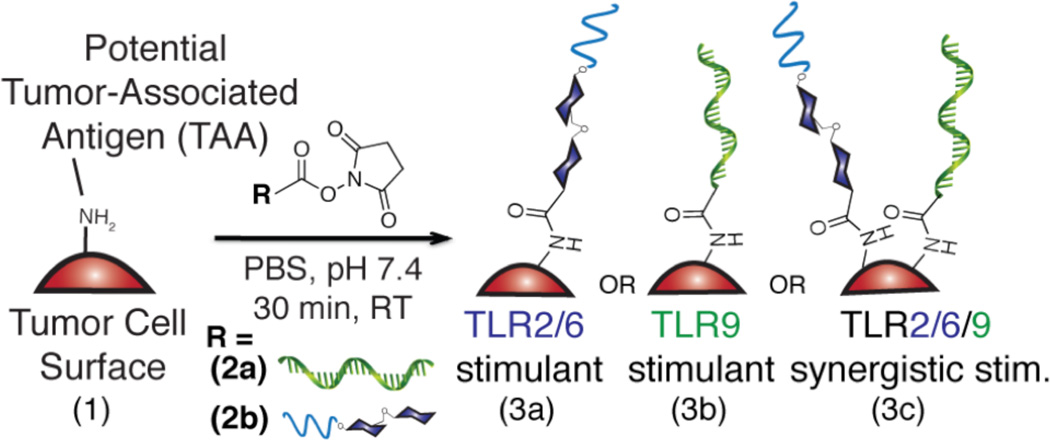

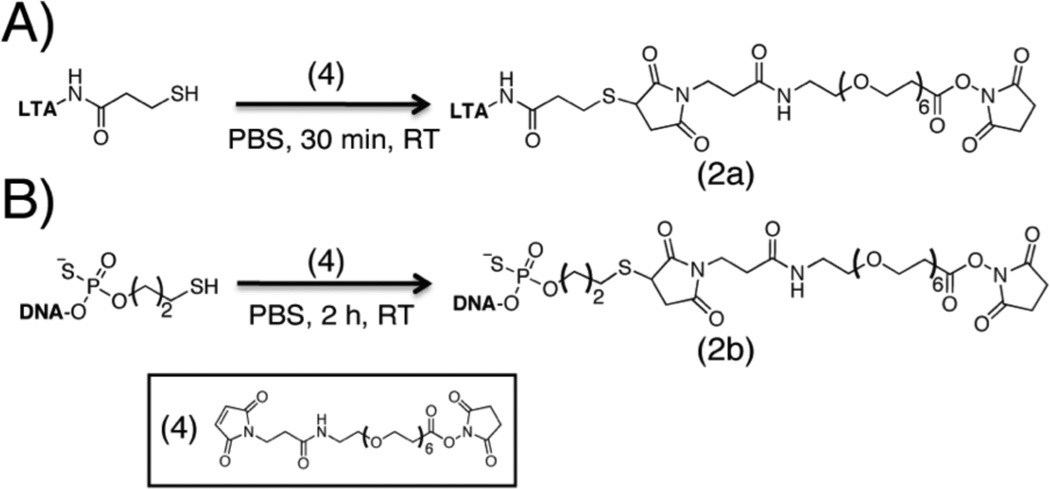

To modify cell surfaces with PAMPs, the first goal was to synthesize PAMP-polymer conjugates that can react with free amines on cell surfaces (Figure 1 & 2). We chose LTA and CpG-ODN1826 as the initial PAMPs, since they are potent TLR agonists and often exhibit a synergistic effect when used in combination.4d,10 Hsiao, et al.11 demonstrated the chemical attachment of ssDNA to cell surfaces via a commercially available, bi-functional SM(PEG)6 linker. The maleimide end of the linker was reacted with a free thiol on each PAMP. For CpG-ODN, as the 5’-end increases stimulation, the 3’-end of CpG-ODN (100 µL, 0.40 mM) was conjugated in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. For LTA attachment, the lipid-tail of LTA is responsible for stimulation, so primary amines along the backbone were thiolated by treating LTA (200 µL, 1 mM) with N-succinimidyl-S-acetylthiopropionate (SATP) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4 with 1 mM EDTA) for 1 h at room temperature (Figure S6). Subsequently, the thiolated LTA was reacted with the maleimide end of the linker in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting conjugate 2a was confirmed via 1H NMR and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Figure S5–S9) and conjugate 2b was confirmed via MALDI-MS (Figure S10).

Figure 1.

The synthesis of immune-stimulating tumor cell surfaces via conjugation of NHSLTA (2a), NHS-CpG-ODN (2b), and both NHS-LTA and NHS-CpG-ODN to Lewis Lung Carcinoma (1) via a SM(PEG)6 linker in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature.

Figure 2.

Scheme illustrating synthesis of PAMP-polymer conjugates (fluorescently tagged conjugates were not used for flow cytometry experiments): A) NHS-LTA (2a) and B) NHSCpG- ODN (2b) were synthesized by treating each thiolated agonist with a SM(PEG)6 linker in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min and 2 h, respectively, at room temperature.

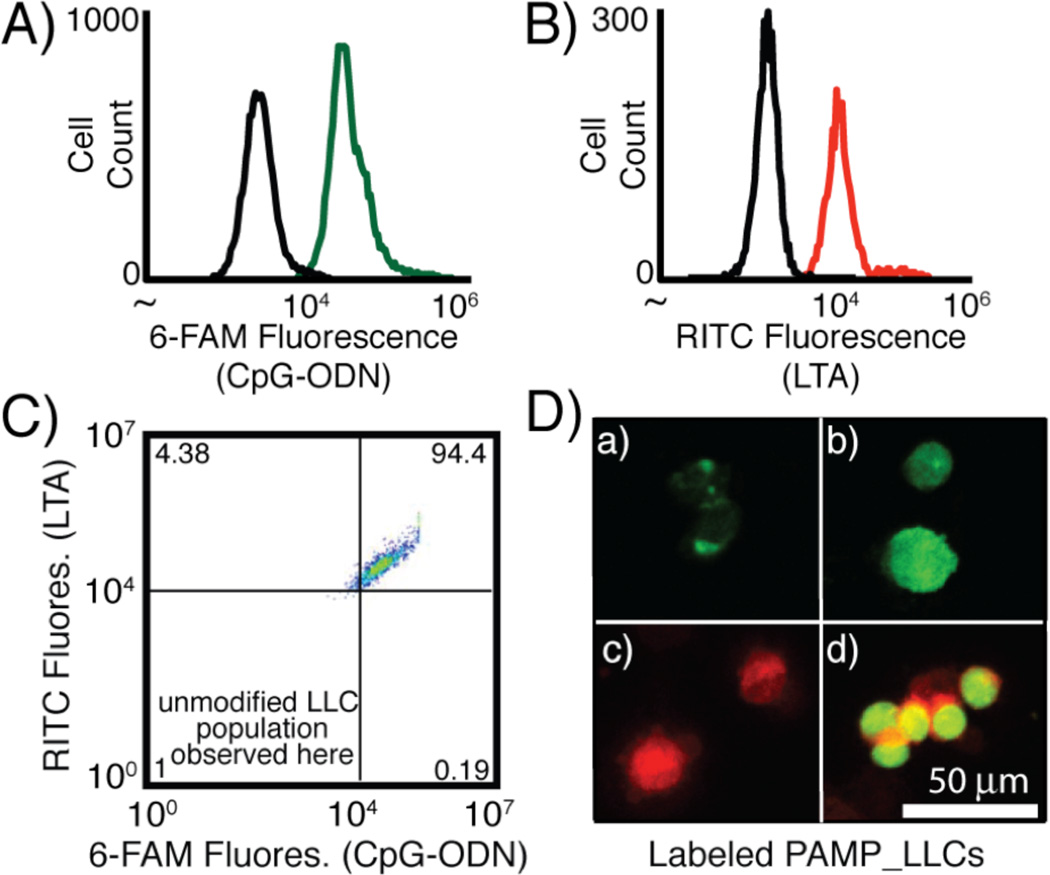

We then sought to conjugate the PAMP-polymer conjugates to Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells. LLC is a model lung cancer cell line often employed in C57Bl/6 mice studies. The NHS ester end-group of each PAMP-polymer conjugate (36 µM, 100 µL) was reacted with free amines on LLC surface proteins in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature. To quantify the modification, CpG_LLCs (3b) were detected by incubating 3b with the 6-FAM tagged anti-sense strand of CpG-ODN1826 (10 µL, 100 µM) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 0 °C.‡ A similar method was used to detect LTA_LLCs (3a), however rhodamine B isothiocyanate was conjugated to amines on the LTA backbone before the modification of LLC cell surfaces (Figure S2–S4). To synthesize CpG_LTA_LLCs (3c), 2a and 2b (in a 1:1 molar ratio) were incubated with LLCs to provide the same total concentration of the two PAMPs as that used for the single PAMP modification (3a or 3b). We confirmed covalent attachment of the PAMP-polymer conjugates using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy (Figure 3). For all LTA and CpG-ODN LLC modifications, we observed a shift in the median fluorescence of the labeled LLCs using flow cytometry, confirming the cell surface modifications (Figures 3A–C). Some non-specific sticking of the fluorescently tagged PAMPs was observed, but distinct populations were observed for all PAMP_LLCs (Figure S11). Using fluorescence microscopy, we also observed fluorescence for each PAMP as well as both PAMPs together in co-localization experiments (Figure 3D).‡‡

Figure 3.

Analysis of fluorescently labeled PAMP_LLCs A) CpG-ODN1826_LLCs incubated with 6-FAM CpG-ODN1826 anti-sense strand in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer for 30 min at 0 °C (unmodified LLCs-black, CpG_LLCs-green), B) RITC LTA_LLCs (unmodified LLCs-black, LTA_LLCs-red), and C) CpG_LTA_LLCs (upper right quadrant). D) Confocal microscopy images (at 488 nm for 6-FAM & 555 nm for RITC) of a) unmodified LLCs incubated with 6- FAM CpG-ODN1826 anti-sense strand exhibiting non-specific sticking, b) CpG_LLCs incubated with 6-FAM CpG1826 anti-sense strand, c) RITC LTA_LLCs, and d) CpG_LTA_LLCs.

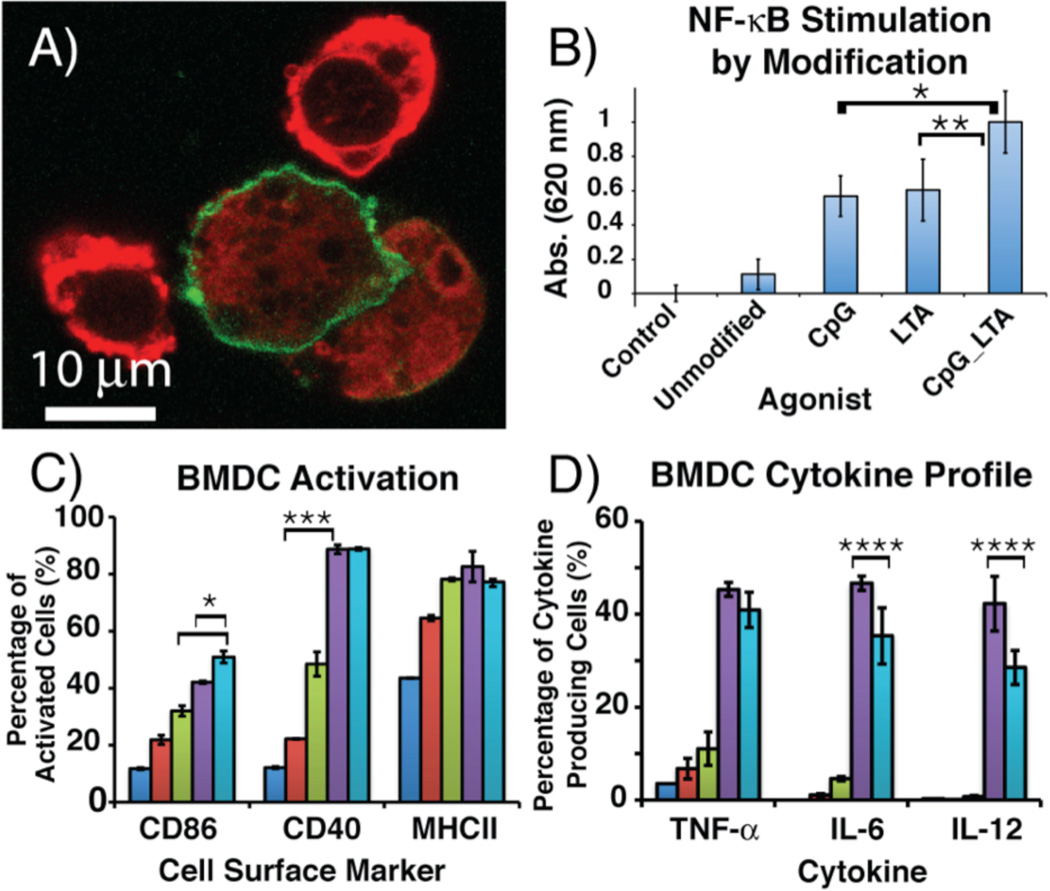

To determine possible mechanisms by which our PAMP_LLCs stimulated APCs, we examined the cells using confocal microscopy. An immortalized dendritic cell-line, JAWS II, was employed as a model owing to its ease of use. APCs were labeled with DiO (green) and our LLC constructs with DiI (red).12 CpG_LLCs were internalized by the APC cell-line, confirming that macrophagocytosis is one possible mechanism by which stimulation proceeds (Figure 4A).‡‡‡

Figure 4.

A) Confocal microscopy image of DiI-labeled CpG_LLCs (red) macrophagocytosed by DiO-labeled dendritic cells (green). B) RAW264.7 macrophage NF- κB stimulation. Macrophages were incubated with PAMP_LLC constructs for 18 h at 37 °C. Each bar is the result of six independent experiments. C) BMDC activation via cell surface marker expression when incubated with PAMP_LLC constructs for 18 h at 37 °C. D) BMDC cytokine profile measured by intracellular cytokine production when incubated with PAMP_LLC constructs for 8 h at 37 °C. IFN-γ and IL-10 secretion was not observed for any PAMP_LLC construct (Figure S18).14 For flow cytometry experiments, control (dark blue), unmodified LLCs (red), LTA_LLCs (green), CpG_LLCs (purple), CpG_LTA_LLCs (light blue). Each result is from three independent experiments, where *p < 0.025, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.1 (see S.I. for entire statistical analysis).

Next, we determined the effect of the PAMP modifications on the stimulation of internal signaling pathways in RAW264.7, a murine macrophage reporter cell-line (RAW-Blue) (Figure 4B). In RAW-Blue cells, NF-κB stimulation is quantified through secretion of alkaline phosphatase using a colorimetric assay. In all experiments involving unmodified cells, we observed little stimulation of the RAW-Blue cell line. Incubating the RAW-Blue cells with 3a or 3b for 18 h at 37 °C displayed a 500% increase of NF-κB expression from the unmodified LLCs. Interestingly, both 3a and 3b stimulated to a similar degree despite interacting with a cell surface and an endosomal PRR, respectively. 3c evoked the greatest NF-κB signaling. Approximately a 200% increase in stimulation was observed compared to a single modification despite 3c contained only half the total cell-surface concentration of each PAMP. This result suggests that covalently conjugating multiple PAMPs to whole cells increases immune activation, which can lower loading levels compared to use of a single PAMP.

To examine potential synergistic effects of covalently attached PAMPs in vivo, we tested PAMP_LLCs against bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs), a standard cell-line used to confirm immune activation in vitro (Figure 4C).13 Activation of BMDCs was confirmed via the upregulation of cell surface markers by flow cytometry and expression of cytokines by intracellular cytokine flow cytometry. To determine cell surface marker expression, BMDCs were incubated with each construct for 18 h at 37 °C. Cell surface markers CD86, CD40, MHC II, and CD80 are proteins involved in priming naïve T-cells to elicit robust T-cell mediated immune responses. The upregulation of these cell surface markers signifies potential T-cell activation, resulting in an adaptive immune response. For unmodified LLCs, minor upregulation of cell surface markers CD86, CD40, and MHC II was observed. Expression of CD80 was also quantified, but the basal level observed was high, resulting in minor upregulation of the CD80 (Figure S15). All of the PAMP_LLCs resulted in enhanced activation of BMDC cell surface markers. Cell surface expression for CD86 was 20% greater for 3b and 30% greater for 3c than unmodified LLCs. 3a displayed greater activation relative to the unmodified LLCs. However, 3a showed modest activation compared to other modified constructs. The discrepancy in activation could be explained by localization of the CpG-ODN modified constructs inside and throughout the cell, resulting in more effective TLR9 stimulation within the endosome.‡‡‡‡ The two PAMP modification, when presented on the same tumor cell, enhanced BMDC activation, which demonstrated the potential for using multiple PAMPs to increase APC activation. All PAMP_LLCs provided increased activation over BMDCs incubated with the unconjugated components at an even higher concentration (Figure S16). This demonstrated that the covalent conjugation of multiple PAMPs to potential tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) can enhance immune activation, indicative of the priming of naïve T-cells.

To determine the cytokine profile elicited by the PAMP_LLC constructs, intracellular cytokine flow cytometry was used to analyze cytokine production (Figure 4D). PAMP_LLCs were incubated with BMDCs for 8 hours at 37 °C. GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences), containing Brefeldin A, was added to cell cultures for the final 4 hours of incubation. 3b elicited the greatest production of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α, all pro-inflammatory cytokines. 3b exhibited nearly a 45% increase of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α production compared to unmodified LLCs. 3c produced the second greatest amount of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α, approximately a 35% increase compared to unmodified LLCs. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines may lead to activation of a cytotoxic T-cell response toward the LLC target antigen, resulting in the recruitment of APCs to the whole tumor cells. It also appeared that the LTA modulated signaling cytokine production, since 3c resulted in approximately a 5–10% decrease in IL-6, IL-12, compared to the 3b while TNF-α cytokine production remained virtually the same. 3a only induced minor IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α production, a 1–5% increase from unmodified LLCs. Our data suggests that the TLR2/6/9 combination resulted in a muted TH1 response while still activating T-cells via CD86 and CD40. This will allow us to simultaneously activate the immune system and modify cytokine production. A combination of TH1/TH2 responses may also be present, which is similar to an effective broad-based vaccine, where both pro-inflammatory (TH1) and anti-inflammatory responses (TH2) are produced. This potential to modulate cytokine production may allow us to direct APC immune responses toward a target antigen.‡‡‡‡‡

In this work, we have presented the first covalent conjugation of PAMPs to antigens on whole cells. A general, modular bioconjugation approach is employed, so different combinations of PAMPs, antigens, and target cell types can be tested. Our studies confirmed that directly and chemically modifying target cell antigens using multiple PAMPs elicited greater stimulation of APC lines. Future immunotherapies can use these techniques to enable lower therapeutic dosage and greater activation of dendritic cells in in vivo immunotherapeutic applications as well as modifying TAAs in biopsied samples. The use of these chemical tools can potentially enhance cell-mediated immunity and create more potent, directed cancer vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by UC Irvine Department of Chemistry and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-0808392 (awarded to J.K.T.).

Footnotes

Notes and additional information are available in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI): See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pulendran B, Artis D. Science. 2012;337:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1221064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pulendran B. Immunol. Rev. 2004;199:227–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu Y-J, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Swartz MA, Hirosue S, Hubbell JA. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:1–11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) De Geest BG, Willart MA, Lambrecht BN, Pollard C, Vervaet C, Remon JP, Grooten J, De Koker S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3862–3866. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ali OA, Huebsch N, Cao L, Dranoff G, Mooney DJ. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:151–158. doi: 10.1038/nmat2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Popkov M, Gonzalez B, Sinha SC, Barbas CF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:4378–4383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900147106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Murelli RP, Zhang AX, Michel J, Jorgensen WL, Spiegel DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17090–17092. doi: 10.1021/ja906844e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Shukla NM, Salunke DB, Balakrishna R, Mutz CA, Malladi SS, David SA. Plos One. 2012;7:e43612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Moon JJ, Suh H, Li AV, Ockenhouse CF, Yadava A, Irvine DJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:1080–1085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112648109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Janeway CA, Medzhitov R. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Basith S, Manavalan B, Lee G, Kim SG, Choi S. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents. 2011;21:927–944. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.569494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Duthie MS, Windish HP, Fox CB, Reed SG. Immunol. Rev. 2011;239:178–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulendran B. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:741–747. doi: 10.1038/nri2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Krummen M, Balkow S, Shen L, Heinz S, Loquai C, Probst H-C, Grabbe S. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;88:189–199. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shukla NM, Mutz CA, Malladi SS, Warshakoon HJ, Balakrishna R, David SA. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1106–1116. doi: 10.1021/jm2010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mäkelä SM, Strengell M, Pietilä TE, Osterlund P, Julkunen I. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009;85:664–672. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0808503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Duggan JM, You D, Cleaver JO, Larson DT, Garza RJ, Pruneda FAG, Tuvim MJ, Zhang J, Dickey BF, Evans SE. J. Immunol. 2011;186:5916–5926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Garcia-Cordero JL, Nembrini C, Stano A, Hubbell JA, Maerkl SJ. Integr. Biol. Quant. Biosci. Nano Macro. 2013;5:650–658. doi: 10.1039/c3ib20263a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Timmermans K, Plantinga TS, Kox M, Vaneker M, Scheffer GJ, Adema GJ, Joosten LAB, Netea MG. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:427–432. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00703-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI, Ravindran R, Stewart S, Alam M, Kwissa M, Villinger F, Murthy N, Steel J, Jacob J, Hogan RJ, García-Sastre A, Compans R, Pulendran B. Nature. 2011;470:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Immunity. 2010;33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Levitz SM, Golenbock DT. Cell. 2012;148:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) DeMuth PC, Garcia-Beltran WF, Ai-Ling ML, Hammond PT, Irvine DJ. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:161– 172. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201201512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Moon JJ, Huang B, Irvine DJ. Adv. Mater. 2012 doi: 10.1002/adma.201200446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H, Kwong B, Irvine DJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7052–7055. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Shirota H, Klinman DM. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. Cii. 2011;60:659–669. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-0973-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goldstein MJ, Varghese B, Brody JD, Rajapaksa R, Kohrt H, Czerwinski DK, Levy S, Levy R. Blood. 2011;117:118–127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Cleveland MG, Gorham JD, Murphy TL, Tuomanen E, Murphy KM. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:1906–1912. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1906-1912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Krieg AM. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:709–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuramoto E, Yano O, Kimura Y, Baba M, Makino T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Kataoka T, Tokunaga T. Cancer Sci. 1992;83:1128–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Shimada S, Kuramoto E, Yano O, Kataoka T, Tokunaga T. Microbiol. Immunol. 1992;36:983–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Tuvim MJ, Gilbert BE, Dickey BF, Evans SE. Plos One. 2012;7:e30596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vollmer J, Krieg AM. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deininger S, Stadelmaier A, von Aulock S, Morath S, Schmidt RR, Hartung T. Clinical and Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1629–1633. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00007-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsiao SC, Shum BJ, Onoe H, Douglas ES, Gartner ZJ, Mathies RA, Bertozzi CR, Francis MB. Langmuir. 2009;25:6985–6991. doi: 10.1021/la900150n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Underhill DM, Bassetti M, Rudensky A, Aderem A. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1909–1914. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matheu MP, Sen D, Cahalan MD, Parker I. J. Vis. Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Krieg AM. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krieg AM, Wagner H. Immunol. Today. 2000;21:521–526. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.