Abstract

Inflammatory signals present in demyelinated multiple sclerosis lesions affect the reparative remyelination process conducted by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)–6 have differing effects on the viability and growth of OPCs, however the effects of IL-17A are largely unknown. Primary murine OPCs were stimulated with IL-17A and their viability, proliferation, and maturation were assessed in culture. IL-17A-stimulated OPCs exited the cell cycle and differentiated with no loss in viability. Expression of the myelin-specific protein, proteolipid protein, increased in a cerebellar slice culture assay in the presence of IL-17A. Downstream, IL-17A activated ERK1/2 within 15 min and induced chemokine expression in 2 days. These results demonstrate that IL-17A exposure stimulates OPCs to mature and participate in the inflammatory response.

Keywords: oligodendrocyte, interleukin-17, ERK, inflammation, myelin, chemokine

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common neurological diseases affecting young adults. The underlying inflammatory autoimmune response against myelin can affect sensory, motor, and cognitive function, and inflammatory signals, or cytokines, play an integral role in the clinical disease course (Rodgers and Miller, 2012). Cytokines involved in MS pathology, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), have been examined for their direct effects on resident central nervous system (CNS) cells to fully appreciate the impact of inflammation on the microenvironment. Of particular interest are oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), the population of cells responsible for the regenerative process of remyelination. Despite the detrimental nature of proinflammatory cytokines on other cell types, cytokines have been shown to have variable effects on OPC function including viability, proliferation, and maturation, and they often have competing effects. For instance, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) inhibit OPC proliferation by enhancing differentiation and survival (McKinnon et al., 1993; Vela et al., 2002). IFN-γ induces concentration-dependent effects: high levels of IFN-γ lead to demyelination, whereas low levels protect mature oligodendrocytes by stressing the endoplasmic reticulum and maintain OPCs in the cell cycle (Chew et al., 2005; Corbin et al., 1996; Lin et al., 2005). TNF-α is destructive to cells throughout the oligodendrocyte lineage, inhibiting OPC proliferation and differentiation while inducing apoptosis in mature oligodendrocytes (Hovelmeyer et al., 2005; Pang et al., 2005). Conversely, proinflammatory IL-6 enhances OPC differentiation and survival even in the presence of glutamate excitotoxicity (Pizzi et al., 2004; Valerio et al., 2002). IL-17A is now recognized as a major cytokine contributing to MS pathology though its effects on OPC viability and differentiation are poorly understood.

The diverse biological functions of IL-17A and its downstream signaling pathways are only beginning to emerge. Since IL-17A was first cloned 20 years ago, researchers have focused on a variety of cell types and mouse models of disease making it difficult to appreciate a single canonical signaling pathway. Using the mouse model of MS, experimental auto-immune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a large body of work has investigated Th17 cells and whether their production of IL-17A is essential to driving immunopathology and disease progression (Codarri et al., 2011; Jager et al., 2009). This stems from an early finding that EAE disease onset and severity were reduced in IL-17−/− mice (Komiyama et al., 2006). Despite this, researchers have only just begun to study how IL-17A affects brain resident cells that are known to express IL-17A receptor (IL-17RA) such as astrocytes, microglia, and neural stem cells (NSCs; Das Sarma et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013).

EAE inflammation is driven by myelin-specific T helper cells, and IL-17A-producing CD4+ Th17 cells specifically are sufficient to adoptively transfer EAE (Korn et al., 2009). Furthermore, EAE disease is at least partially resolved by an IL-17A-neutralizing monoclonal antibody or an IL-17 receptor-blocking Fc-protein (Hofstetter et al., 2005; Miossec et al., 2009). IL-17RA expression increases throughout the CNS gray matter at peak of EAE disease when infiltrating Th17 cells extensively produce IL-17A thereby increasing CNS vulnerability (Das Sarma et al., 2009). The specific cells upregulating IL-17RA in the CNS, however, remain unknown. Astrocytes and microglia have been shown to be responsive to IL-17A in vitro as measured by their production of chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL2, CCL12, CCL20, and the cytokine IL-6, but IL-17A effects on OPCs and remyelination remain to be seen (Elain et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2010).

Given that IL-17A is produced by Th17 cells and is known to be present in active MS lesions (Hedegaard et al., 2008; Lock et al., 2002), we sought to understand how IL-17A affects the oligodendrocyte lineage. IL-17A effects on other CNS progenitor cells, specifically NSCs, have been described. NSCs stimulated with IL-17A showed reduced proliferation yet did not apoptose (Li et al., 2013). IL-17A increased total p38 levels and restricted NSC differentiation to neurons, astrocytes, and OPCs (Li et al., 2013). Here we demonstrate that IL-17A stimulated OPCs to exit the cell cycle and differentiate with no change in viability using immunohistochemistry, molecular techniques, and a technique we have recently described to characterize oligodendroglial cells by flow cytometry (Robinson et al., 2014). Similar to developmental myelination pathways, IL-17A activated ERK1/2 in OPCs. IL-17A also increased myelin levels in an ex vivo cerebellar slice culture assay, indicating that IL-17A could be beneficial for remyelination.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Naïve C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories, breeder IL-17RA KO mice were obtained from Amgen, and breeder PLP-GFP mice were obtained from Wendy Macklin. Mice were housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL. All protocols (2010-0357) were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with Federal Animal Welfare Regulations.

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) was induced in 5–7-week-old C57BL/6 females by subcutaneous immunization with 100 μL of an emulsion of 200 μg MOG35–55 peptide (Genemed Synthesis Inc,) and complete Freund’s adjuvant (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing 4 mg/mL Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco, Detroit, MI). An intraperitoneal injection of 200 ng pertussis toxin (List Biologicals) was administered on the day of priming and 2 days later. Clinical disease for each mouse was graded on a routine scale of 0 to 5. At peak disease (~Day 13), CNS tissue (brain and spinal cord) was analyzed by flow cytometry and compared with naive mice.

CNS Tissue Preparation and Flow Cytometry

Mice were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital and perfused with 30 mL PBS through the left ventricle. Spinal cords were removed and placed in PBS on ice. Tissue was minced and enzymatically dissociated with Accutase (Millipore) for 30 min at 37°C. Accutase was quenched with 30% FBS and tissue was triturated with a 1 mL pipette until a single cell suspension was achieved. The suspension was filtered through a 100-μm filter, spun down at 1700 rpm for 3 min, and resuspended in 40% percoll (Sigma) in HBSS at room temperature. Cells were spun down at 650g for 25 min at RT. The top myelin layer and percoll was aspirated off and the cell pellet was washed with PBS. Cells were counted with a haemocytometer and at least 105 cells were used per sample for flow cytometry.

Cells were blocked for 30 min at 4°C with 2.5% mouse and 2.5% rat serum (Sigma), and washed with PBS. Live cells were stained for 30 min at 4°C with Calcein Blue (Life Technologies). Purified antibodies were conjugated to PE, FITC, PerCP, and PE-Cy7 using Lightning-Link Antibody Labeling Kits (Novus Biologicals) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with 1 μg/test mouse anti-NG2, Millipore; 0.5 μg/test mouse anti-A2B5, R&D Systems; 1 μg/test mouse anti-Galactocerebroside (GC), Millipore; and 1 μg/test goat anti-IL-17RA, R&D Systems for 30 min at 4°C in flow cytometry buffer (PBS; 0.5 mM EDTA, 2.5% mouse and 2.5% rat serum). Cells were washed with PBS and analyzed.

Data was acquired with a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) in the Northwestern University Immunobiology Flow Cytometry Core Facility and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Single stain control samples were used for establishing voltages and compensating spectral overlap in FlowJo before analysis. Gating was based on “fluorescence minus one” strategy and isotype control samples. Cell populations were gated on a size and density gate, single cell gate, and live cell gate before gating on OPC-specific antigens.

Primary Mouse OPC Isolation and Culture

Cells were dissociated and purified based on previously described immunopanning protocols (Barres et al., 1992). Briefly, brains were dissected from postnatal days 5–7 C57BL/6 pups, minced, and treated with 200U papain (Worthington Biochemical), 200 ug L-cysteine, and 2500 U DNase (Worthington Biochemical) in a buffered solution (EBSS, 100 mM MgSO4, 30% glucose, 0.5 M EDTA, 1 M NaHCO3) under 95% O2/5% CO2 for 30 min at 37°C. The digestion was ended with 1.5 mg ovomucoid (Worthington Biochemical), and the tissue was mechanically triturated into a single cell suspension.

Cells were resuspended in panning buffer (PBS; 0.02% BSA; 5 ug/mL insulin) and incubated on a negative selection plate for astrocytes and microglia. Negative selection plates were previously coated with goat anti-mouse IgM and IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch) followed by hybridoma supernatant specific for Ran-2 (Hybridoma Bank, Cytometry and Antibody Technology Facility, the University of Chicago, courtesy of Brian Popko). Cells were transferred to a positive selection plate for OPCs. The positive selection plate was previously coated with goat anti-IgM μ-chain (Jackson Immunoresearch) followed by hybridoma supernatant specific for O4 (Brian Popko). Cells were washed with PBS, lifted with 0.25% trypsin (Life Technologies), and quenched with 30% FBS.

Cells were resuspended in a serum-free OPC medium (DMEM, Life Technologies; 5 μg/mL insulin; 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate; 5 μg/mL biotin; SATO supplement; 5 μg/mL N-acetyl-L-cysteine; 2 mM L-glutamine; B-27 Plus without vitamin A; 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) supplemented with growth factors to promote proliferation (10 ng/mL rhPDGF-AA, 10 ng/mL rhCNTF, 10 ng/mL rhNT-3, all Peprotech; and 10 μM forskolin, Sigma). Cells were plated at 1 × 106 on 10 cm2 poly-D-lysine (Sigma)-coated plates and grown at 37°C with 10% CO2. Half of the medium was replaced every 2 days.

Primary Mouse OPC Proliferation Assay

OPCs were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated eight-well glass chamber slides (BD Biosciences). After 48 h half of the OPC medium was replaced with or without 2x recombinant mouse IL-17A for a final concentration of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL IL-17A (R&D Systems). After an additional 48 h, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at RT. For immunocytochemistry cells were blocked with 10% donkey serum/1% BSA then stained for Ki67 (1:500 rabbit-anti-Ki67, Abcam; 1:1000 Alexa 488 donkey-anti-rabbit, Life Technologies). Cells were counter-stained with DAPI and imaged using an EVOS fluorescent microscope (Life Technologies) with 20× and 40× magnification objectives. Ki67+ cells were counted out of 200 cells in each well. The scorer was blinded to the experimental group. Proliferation was calculated as the percentage of Ki67+ cells out of total cells.

Primary Rat OPC Culture and Differentiation Assay

OPCs were purified from the brains of P6 Sprague-Dawley rats via immunopanning as described previously (Cahoy et al., 2008). 96-well tissue culture plates were coated with poly-D-lysine for 30 min and laminin for one hour. OPCs were added in basal OPC medium containing NT3 (1 ng/mL, Peprotech) either with 10 ng/mL PDGF at 1000 cells/well or without PDGF at 5000 cells/well. 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A, T3 (40 ng/mL, Sigma), or the same volume of medium was added 2 h later. Cultures were maintained at 37°C, 10% CO2 for three days (-PDGF cultures) or 6 days (+PDGF cultures). Half of the medium was changed after 3 days including IL-17A or T3 as previously added. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by immunostaining for myelin basic protein (MBP) expression (1:500 rat-anti-MBP, Abcam; 1:1000 Alexa 488 goat-anti-rat, Life Technologies). Cultures were counterstained with DAPI and robotically imaged using an automated stage with Nikon NIS Elements software. Images were then analyzed with GE InCell software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to score the intensity of MBP staining in an approximately 40-μm shell around each DAPI-stained nucleus. A fluorescence intensity threshold was defined and measured for each sample to determine the percentage of OPCs versus mature oligodendrocytes in each well. Approximately 150–300 cells were scored for each well, data was averaged across the entire well, and eight replicate wells were generated for each condition tested.

Primary Mouse OPC Viability Assay

OPCs grown on 10 cm2 plates were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A. After 2 days in culture, supernatants were collected and cells were lifted with 0.25% trypsin (Sigma) for 8 min at 37°C, quenched with 30% FBS, and blown off by pipet. Cells were combined with supernatants and counted. 100 nM tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester, perchlorate (Life Technologies) was added to cells for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed with PBS and stained with anti-Annexin-V (1:100, Life Technologies) and 150 μM propidium iodide (PI) for 15 min in Annexin binding buffer. Cells were washed and analyzed with an LSRII cytometer. Single stains were used to set voltages on the cytometer and compensation in FlowJo before analysis. Gating was defined by “fluorescence minus one” control samples.

Primary Mouse OPC Signaling Pathway Analysis

OPCs grown on 10 cm2 plates were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A. Cells were collected 5, 15, 30, or 60 min after IL-17A addition. For active caspase 3 analysis, cells were additionally cultured 12 and 24 h. Cells were washed with PBS then collected by cell scraper in 300 μL MILLIPLEX lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore). Protein was quantified with the Quantit Protein Quantifying Kit (Life Technologies) and 20 μg protein was analyzed using MILLIPLEX Multiplex Assays for intracellular signaling molecules according to manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore). Phosphorylated IkB was assayed by ELISA according to manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for phosphorylated molecules were normalized to the total amount and reported relative to unstimulated controls.

Primary Mouse OPC Chemokine and Cytokine Microarray

OPCs grown on 10 cm2 plates were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A or 100 ng/mL IFN-γ. After 2 days, cells were washed with PBS and collected with a cell scraper into 1 mL lysis buffer from the μMACS mRNA Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). mRNA was isolated using μMACS Magnetic Separator, and cDNA was synthesized on the column with the μMACS One-step cDNA Kit. Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green and RT2 Profiler PCR Array Mouse Chemokines and Cytokines (Qiagen) using a Bio-Rad iQ5 thermocycler. Data was analyzed with the iQ5 software. Relative gene expression was calculated by normalizing to the housekeeping gene, rlp13a, and expressed as a fold change from the unstimulated negative control sample for each genotype. Microarray assays were performed two independent times.

Cerebellar Slice Culture and Myelination Analysis

Postnatal Day 10 transgenic mice expressing GFP under the proteolipid protein (PLP) promoter were sacrificed. Brains were rapidly removed and cerebella isolated. Cerebella were transferred to a McIlwain tissue chopper (Ted Pella) and sliced in the sagittal plane into 350 mm sections. Slices were transferred to 0.4 μm pore hydrophobic membranes with underlying slice culture growth medium (Opti-MEM:HBSS (1:1) with 25% horse serum, and 0.5% glucose; all Sigma). Medium was changed every other day. Slices were allowed to stabilize in culture at least one week. 50 μM PI was added to the culture medium to assess cell death.

Slices were cultured with 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL rIL-17A with or without 5.1 nM ERK inhibitor in DMSO (FR180204, Millipore, n = 6 slices per treatment). Photomicrographs of slices were acquired before treatment and 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after beginning of treatment using a Nikon AZ dissecting microscope with 4× magnification objective (myelin: green channel, cell death: red channel). Imaging was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553. Individual channels were converted to grayscale (intensity range: 0–255) using ImageJ (NIH). A threshold value was set using pretreatment images for each slice. Threshold values were applied to individual slices throughout the time course. The integrated density was calculated for each slice at each time point. Values were normalized to the pretreatment values.

mRNA and Protein Analysis in Cerebellar Slices

Cerebellar slices were cultured with 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL rIL-17A for 48 or 96 h. Slices were washed with PBS and collected with a cell scraper in 1 mL of lysis buffer from the μMACS mRNA Isolation Kit. mRNA was isolated using μMACS Magnetic Separator, and cDNA was synthesized on the column with the μMACS Onestep cDNA Kit. Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green and primers for Mbp (Band size: 129 bp, Reference position: 732, Qiagen) using a Bio-Rad iQ5 thermocycler. Data was analyzed with the iQ5 software. Relative gene expression was calculated by normalizing to the housekeeping gene, rlp13a, and expressed as a relative change from the unstimulated slices at 48 and 96 h.

For protein analysis, cerebellar slices were cultured with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL IL-17A for 96 hours. Slices were collected by cell scraper, transferred to 300 μL MILLIPLEX lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail, and homogenized with an Omni Mixer. Protein was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay and 1 μg of protein was separated on a gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with 0.5 μg anti-MBP (clone SKB3, Millipore). The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with 1 μg anti-beta-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made between groups by one-way or two-way ANOVA, assuming normal distribution, and post hoc Bonferroni tests comparing between groups. Where indicated comparisons were made between groups using an unpaired Student’s t test. For all statistical analyses, P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All error bars are representative of one standard deviation. Each experiment was performed a minimum of three times except where indicated.

Results

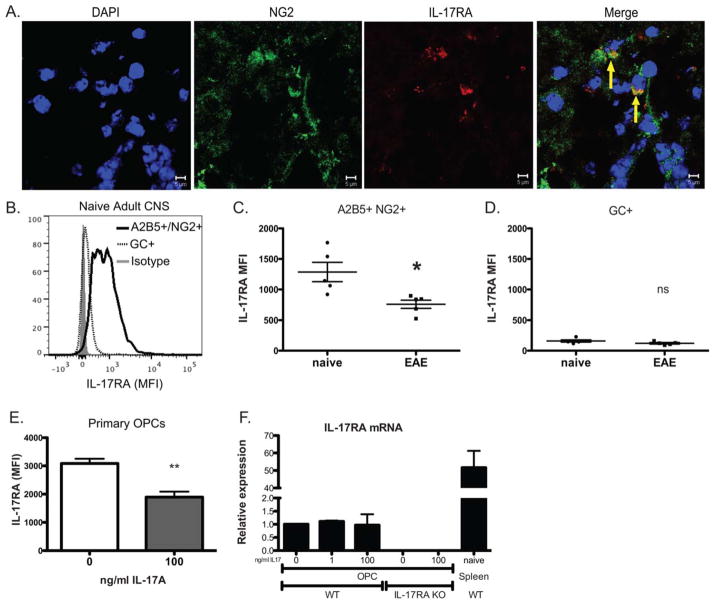

OPCs Express IL-17RA In Vitro and In Vivo

Several oligodendroglial populations were assessed for IL-17RA expression to determine sensitivity to IL-17A signaling. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the expression of IL-17RA by NG2+ cells in the spinal cord of mice during the peak phase of EAE (Fig. 1A). Additionally, we examined the MFI of IL-17RA staining on live oligodendroglial cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). Both A2B5+/NG2+ OPCs and GC+ mature oligodendrocytes expressed IL-17RA with OPCs expressing a higher level. It was previously reported that IL-17RA is globally upregulated in the CNS at peak of EAE disease (Das Sarma et al., 2009), and we have recently reported that NG2+ OPCs are increased in the spinal cord at peak disease (Robinson et al., 2014). To determine whether OPCs or oligodendrocytes increase IL-17RA expression during EAE, we determined IL-17RA levels by flow cytometry. Surprisingly, A2B5+/NG2+ OPCs had significantly reduced IL-17RA expression at peak disease compared with naïve mice, whereas expression on GC+ oligodendrocytes did not change (n = 5, Fig. 1C,D). To determine whether OPCs reduced IL-17RA in response to IL-17A, we cultured mouse OPCs with or without IL-17A. After 48 h, there was a significant reduction in the level of IL-17RA on the cell surface of OPCs (n = 4; Fig. 1E). To determine whether the regulation of IL-17RA occurred at the transcription level, IL-17RA mRNA was quantified by RT-PCR. After 48 h IL-17RA mRNA levels in OPCs did not change in response to IL-17A (Fig. 1F) suggesting that IL-17A-mediated regulation occurs after transcription. IL-17RA mRNA’s were further undetectable in OPCs from IL-17RA KO mice that lack the common receptor subunit IL-17RA cultured with or without IL-17A.

FIGURE 1.

OPCs express IL-17RA in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative photomicrograph of spinal cord from a C57BL/6 adult mouse immunized with MOG35–55 in CFA, harvested at peak disease, and stained for NG2 (green), IL-17RA (red), and DAPI (blue). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of IL-17RA staining of A2B5+NG2+ OPCs and GC+ oligodendrocytes isolated from C57BL/6 mice compared with the isotype control. IL-17RA expression on the cell surface of A2B5+NG2+ OPCs (C) and GC+ oligodendrocytes (D) from naïve C57BL/6 and MOG35–55/CFA immunized mice at peak disease (n = 5, OPCs, P < 0.05; oligodendrocyte, ns). (E) IL-17RA expression on the cell surface of primary OPCs cultured with or without 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A for two days (n = 4, P < 0.01). (F) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of IL-17RA transcripts in OPCs from WT or IL-17RA−/− mice stimulated with or without 1 or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A for two days. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

IL-17A Reduced OPC Proliferation

To determine if IL-17A affects OPC function, we first examined proliferation. Mouse OPCs were cultured with increasing concentrations of IL-17A, and Ki67, a marker for dividing cells, was assayed by immunohistochemistry. IL-17 reduced Ki67 in a concentration-dependent manner, specifically 0.1 ng/mL (P<0.05), 1 ng/mL (P<0.001), 10 ng/mL (P<0.001), and 100 ng/mL (P<0.001) IL-17A, but not 0.01 ng/mL (n = 4, Fig. 2A,B). Reduced Ki67 in response to IL-17A was corroborated by flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). These data confirm that OPCs express a functional level of IL-17RA and that IL-17A drives OPCs to exit the cell cycle.

FIGURE 2.

IL-17A-stimulated OPCs exit the cell cycle. OPCs from C57BL/6 pups were cultured with 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A for two days and mitotic cell division was measured by Ki67 staining (A: Ki67, green; nuclei, blue) and blindly quantified (B: n = 3, * P < 0.05, *** P< 0.001). Cell division was verified by flow cytometric analysis (C). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

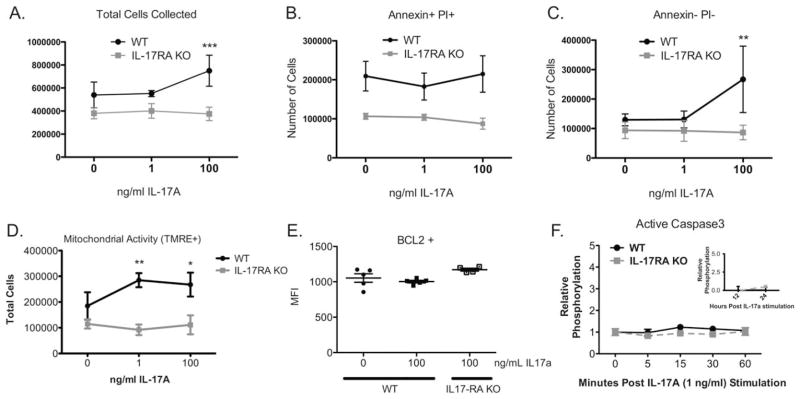

IL-17A Did Not Induce Cell Death in OPCs

TNF-α and IFN-γ have been shown to induce cell death in rat OPCs (Corbin et al., 1996; Pang et al., 2005). To determine whether IL-17A similarly affects the viability of OPCs, we cultured mouse OPCs from wild type (WT) and IL-17RA KO mice with IL-17A and quantified cell death by flow cytometry for Annexin V and PI. Since OPCs are adherent in culture, presumptive dead cells in the supernatants were collected with the adherent cells. Significantly, more WT OPCs stimulated with 100 ng/mL IL-17A were collected than IL-17RA KO OPCs (n = 3, P<0.001, Fig. 3A). IL-17A significantly increased the number of Annexin V−/PI− live cells but did not affect the number of Annexin V+/PI+ dead cells (Fig. 3B,C). To directly assay live cells, we next measured mitochondrial activity. One and 100 ng/mL IL-17A significantly increased the number of WT OPCs with active mitochondria compared with IL-17RA KO OPCs (n = 3, Fig. 3D). To investigate whether IL-17A induced anti-apoptotic signaling, we examined B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2). There was no significant difference in BCL2 expression between unstimulated OPCs and those cultured with 1 or 100 ng/mL IL-17A (n = 5, Fig. 3E). IL-17A also did not activate caspase3 within the first hour, or at 12 or 24 h following stimulation (n = 3, Fig. 3F). Collectively, we found that IL-17A increased the number of OPCs without inducing cell death. Further there was no evidence of anti-apoptotic factors induction.

FIGURE 3.

IL-17A-stimulated OPCs do not undergo apoptosis. OPCs from C57BL/6 and IL-17RA−/− pups were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A for two days. (A) Total cells collected from each plate and supernatant were compared by genotype (pooled per plate, n = 3, *** P < 0.001). Cells were stained for Annexin V and PI. Apoptotic, dead cells (B: AnnexinV+ PI+) and nonapoptotic, live cells (C: AnnexinV− PI−) were quantified by flow cytometric analysis (n = 3, ** P < 0.01). (D) Cells with active mitochondria were quantified by tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE) staining and flow cytometric analysis (n = 3, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01). (E) Cells were stained for B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) and quantified by flow cytometric analysis (n = 4, ns). (F) Active caspase 3 was analyzed by a cytometric bead assay from primary C57BL/6 and IL-17RA−/− OPCs lysed after 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min of 1 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A stimulation (n = 3, ns). Active caspase 3 was also assayed in WT OPCs following 12 and 24 h of IL-17 stimulation (inset). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

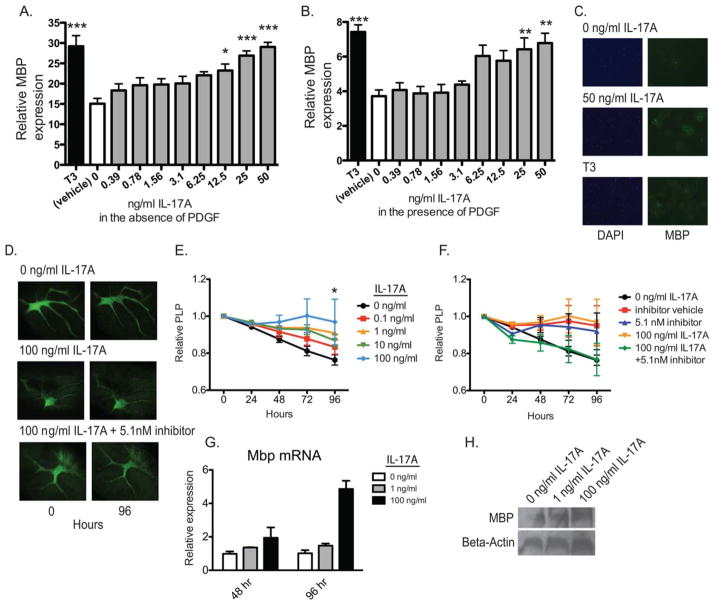

IL-17A Enhanced OPC Differentiation

Cytokines such as IL-1β and TGF-β have been shown to simultaneously enhance OPC differentiation while reducing proliferation (McKinnon et al., 1993; Vela et al., 2002). To determine whether IL-17A affects differentiation, we cultured OPCs in proliferation or differentiation medium with or without IL-17A. Maturation was measured by MBP expression using a high-throughput fluorescence microscopy assay. IL-17A enhanced MBP expression in OPCs grown in differentiation medium in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A,C). Additionally, IL-17A enhanced MBP expression in proliferation medium suggesting it was sufficient to override the proliferative signal of PDGF (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that IL-17A stimulates OPC maturation in addition to inhibiting proliferation.

FIGURE 4.

IL-17A enhanced OPC differentiation. (A–C) OPCs from postnatal rats were cultured with varying concentrations of recombinant IL-17A in the absence (A) or presence (B) of PDGF, stained with MBP by immunocytochemistry, and expression for each group was compared with the unstimulated negative control and triiodothyronine (T3)-treated positive control for differentiation (n = 8, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001). Representative photomicrographs of OPC cultures grown in the absence of PDGF (C). (D–F) Cerebella from postnatal PLP-GFP mice were sliced into 350 μm sections, and cultured on hydrophobic 0.4-μm pore size membranes for 96 hours with or without 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A. Slices were photographed every 24 hours, and PLP levels were assessed by the integrated density of fluorescence intensity for each slice over time with ImageJ software (E, n = 6, * P < 0.05). PLP-GFP cerebellar slices were cultured with 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A and/or an ERK1/2 inhibitor or DMSO vehicle and compared with unstimulated and vehicle controls (F, n = 6, ns). Representative photomicrographs of slice cultures (D). (G–H) Cerebellar slices were cultured for 48 or 96 hours with or without 1 or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A. Mbp mRNA was quantified by RT-PCR (G) and MBP by Western blot (H). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

The effects of IL-17A on OPC differentiation were also assayed in an ex vivo slice culture assay where slices of cerebella from postnatal PLP-GFP mice were stimulated with 0 to 100 ng/mL IL-17A and imaged every 24 h by microscopy (Fig. 4D). PLP signal increased significantly in the slices stimulated for 96 h with 100 ng/mL IL-17A compared with unstimulated controls (n = 6, P <0.05, Fig. 4D,E). To verify these findings, cerebellar slices were cultured for 48 or 96 h with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL IL-17A and differentiation was assayed by RT-PCR and Western blot for MBP. IL-17A significantly increased Mbp transcripts (Fig. 4G) and MBP protein in cerebellar slices (Fig. 4H).

IL-17A Stimulated ERK/MAPK Signaling in OPCs

IL-17A is known to signal through several intracellular pathways in immune cells such as ERK, p38, Akt, and NF-κB (Chen et al., 2011). To investigate signaling in OPCs, total ERK, p38, and NF-κB (p65) were quantified by cytometric bead array after 2 days of IL-17A stimulation. Total ERK and p38 protein were significantly higher in WT OPCs stimulated with IL-17A compared with IL-17RA KO OPCs whereas NF-κB (p65) remained unchanged (n = 3, P <0.05, Fig. 5A–C). Phosphorylation levels were then quantified for ERK, p38, Akt, and IκB within the first 60 min of IL-17A stimulation and normalized to total respective protein. ERK phosphorylation increased significantly within 15 min and remained elevated at 60 min in WT OPCs but did not change in IL-17RA KO (Fig. 5D). There was no change in phosphorylation of p38, Akt, or IκB suggesting IL-17A specifically activates the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway in OPCs (Fig. 5E–G). To determine whether the effects of IL-17A in the slice culture assay were mediated by ERK, slices were stimulated with IL-17A with or without an ERK inhibitor. Although not significant there was a clear trend towards the ERK inhibitor reversing the IL-17A-mediated increase in PLP (n = 6, Fig. 4D,F).

FIGURE 5.

ERK1/2 MAPK is activated in IL-17A-stimulated OPCs. OPCs from C57BL/6 and IL-17RA−/− pups were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A for two days and protein for total ERK (A), p38 (B), and NFkB (p65) (C) were quantified with a cytometric bead assay. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 (D), phosphorylated p38 (E), and phosphorylated Akt (F) levels were quantified in C57Bl/6 and IL-17RA−/− OPCs after 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes of 1 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A stimulation. Phosphorylated IkB was assayed in WT OPCs (G, n=3, * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

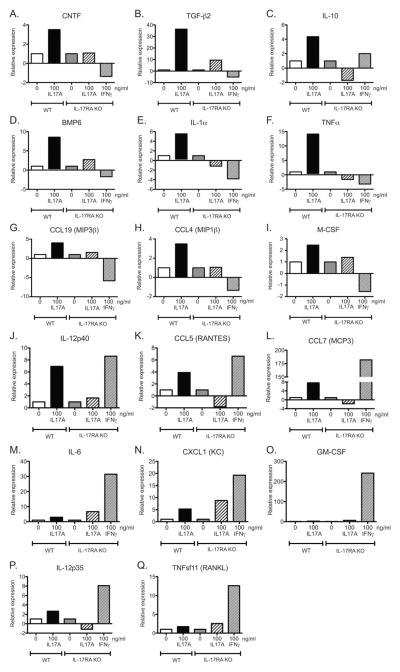

IL-17A Induced Chemokine Expression in OPCs

To further assess downstream functional effects, cytokine and chemokine expression were assessed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR on WT and IL-17RA KO OPCs cultured with or without IL-17A. We also examined IL-17RA KO OPCs stimulated with IFN-γ. IL-17A specifically upregulated transcription of nine cytokines and chemokine molecules: CNTF, TGF-β2, IL-10, BMP6, IL-1α, TNF-α, CCL19, CCL4, and M-CSF (Fig. 6A–I). IL-17A and IFN-γ both upregulated expression of IL-12p40, CCL5, CCL7, IL-6, CXCL1, GM-CSF, and IL-12p35 (Fig. 6J–O). However, IL-6 and CXCL1 were also slightly increased in IL-17RA KO OPCs suggesting possible low affinity binding to other IL-17R subunits or other known or unknown cytokine receptors. IFN-γ but not IL-17A upregulated GM-CSF, IL-12p35, and TNFsf11 in WT OPCs. These results suggest that OPCs participate in the inflammatory response in a cytokine/chemokine specific manner.

FIGURE 6.

IL-17A stimulated OPCs express a specific set of chemokines and cytokines. OPCs from C57BL/6 and IL-17RA−/− pups were stimulated with 0, 1, or 100 ng/mL recombinant IL-17A or 100 ng/mL IFN-γ for 2 days. Transcript levels for CNTF (A), TGF-β2 (B), IL-10 (C), BMP6 (D), IL-1α (E), TNF-α (F), CCL19 (G), CCL4 (H), M-CSF (I), IL-12p40 (J), CCL5 (K), CCL7 (L), IL-6 (M), CXCL1 (N), GM-CSF (O), IL-12p35 (P), and TNFsf11 (Q) were assayed by real time RT-PCR, normalized to housekeeping genes, and the fold change was expressed relative to unstimulated controls by genotype. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Discussion

In MS and EAE infiltrating inflammatory cells and signals are characteristic of the demyelinated lesion. OPCs routinely replace oligodendrocytes in the CNS making them crucial for remyelination and functional recovery. Here, we examined IL-17A, now believed to be a critical component of MS pathology, for its effects on OPCs to better understand de- and remyelination.

We began by demonstrating IL-17RA expression by mouse NG2+A2B5+ OPCs in vitro and in vivo corresponding with previous reports of expression by rat OPCs, an OPC cell line, and NSCs (Li et al., 2013; Paintlia et al., 2011). NG2+A2B5+ OPCs expressed more IL-17RA than GC+ oligodendrocytes. Even though there is global upregulation of IL-17RA expression in the CNS at EAE peak disease (Das Sarma et al., 2009), OPCs reduced their expression. This reduction was not regulated at the transcription level as IL-17RA mRNA levels did not change suggesting post-transcriptional regulation. To determine whether IL-17A directly induced a downregulation of IL-17RA in a paracrine negative feedback loop, OPCs were stimulated in culture with IL-17A, and IL-17RA was quantified. Indeed IL-17RA levels were reduced.

We next performed dose-response studies to investigate IL-17 effects on OPC proliferation and determine effective concentrations for in vitro studies. OPCs proliferated in the presence of PDGF, however exposure to IL-17A for 2 days triggered cells to exit the cell cycle. IL-17A may have limited the proliferation of OPCs by reducing the overall viability or enhancing the differentiation of OPCs. Previous reports indicated that IL-17A-stimulated NSCs did not undergo apoptosis despite an increase in cell cycle exiting (Li et al., 2013). However, Kang et al. showed cell death in rat OPCs cultured with IL-17 and TNF-α though not IL-17A alone (Kang et al., 2013; Paintlia et al., 2011). Similar to the NSC experiments we found that IL-17A-stimulated OPCs exited the cell cycle without increased cell death. Indeed, the overall number of cells increased with IL-17 treatment, an observation we attributed to IL-17 inhibiting the background level of cell death in cultures. Nonetheless, it is possible that the proliferation and cell death responses are sensitive to the source of OPCs and the specific stage within the lineage.

Next, we examined IL-17 for effects on OPC differentiation in a high throughput assay. IL-17A did not inhibit but rather enhanced maturation even in the presence of PDGF. These results were undeniably sensitive to the timing and dose of stimulation, that is, these effects were only observed when IL-17A was introduced within the first two hours of plating (data not shown). Moreover, the dose of IL-17A required to drive differentiation was significantly greater than that required to inhibit proliferation allowing for the possibility that the effects are autonomous and dose-dependent. These findings are a novel contrast to other studies of IL-17A effects on CNS progenitor cells. Li et al. (2013) found IL-17A reduced differentiation of NSCs into OPCs, astrocytes, and neurons (Li et al., 2013). Additionally, Kang et al. demonstrated that differentiating OPCs had limited myelin gene expression in response to IL-17A (Kang et al., 2013). The sensitivity of OPCs to the timing of IL-17A stimulation and the reduction of IL-17RA during differentiation suggest OPCs may be sensitive to IL-17A during a brief window but that the effects on differentiation may be long lasting. The contrasting results could be due to a difference in timing, exposure, or stage of cells within the oligodendrocyte lineage. Taken together these data suggest that differentiation of early multipotent progenitors such as NSCs are limited by IL-17A signaling, but later O4+ OPCs may be encouraged to differentiate by IL-17A.

ERK signaling is essential for developmental OPC differentiation and myelination (Fyffe-Maricich et al., 2011). Our results suggest IL-17A promotes OPC differentiation in part through the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. These results have particular implications for remyelination as OPCs can often be found surrounding demyelinating lesions in MS and EAE that are characterized by CD4+ T cells producing IL-17A (Maeda et al., 2001; Wolswijk, 2000). In 2013, Kang et al. created mice with conditional knock out (cKO) of act1, an IL-17RA adaptor signaling molecule, in CNS cells. Mice with NG2- and olig2-specific cKO of act1 presented delayed and attenuated EAE clinical symptoms whereas mice lacking act1 in astrocytes, neurons, or mature oligodendrocytes developed normal disease (Kang et al., 2013). These results specifically identify OPCs as critical, brain-resident responders to IL-17A during EAE and parallel our finding that OPCs are more sensitive to IL-17A signaling than mature oligodendrocytes. They concluded that IL-17A in EAE directly induced OPC death as seen with oligospheres in their cultures, although this does not exclude different IL-17A effects depending on the developmental stage of the OPC. Indeed our OPCs from naïve mice and OPCs in EAE mice may have been at different developmental stages. Our cultured OPC data are further supported by our finding that IL-17A increased myelin levels in cerebellar slice cultures suggesting that, at least under certain conditions, IL-17A may not be harmful to remyelination efforts but rather conducive. Indeed inflammation driving OPC myelination has been demonstrated before (Setzu et al., 2006).

Our data suggest that besides promoting differentiation a major function of IL-17A in OPCs is eliciting production of chemokines and cytokines. CNTF is a survival factor for neurons and oligodendrocytes and contributes to OPC migration during remyelination (Vernerey et al., 2013). Along with this direct benefit to oligodendrocytes, TGF-β2 and IL-10 have regulatory/anti-inflammatory effects on effector T cells (Peterson, 2012). The remaining IL-17A-induced molecules are proinflammatory, and the chemokines specifically are known to attract lymphocytes to sites of inflammation (Comerford et al., 2013; Szczucinski and Losy, 2007). IL-12p40 contributes to Th1 cell maintenance, and CCL5 and CCL7 are potent chemokines for T cells and monocytes. Indeed IL-17A drives production of a complex set of chemokines and cytokines that will be worth further exploring for their role in EAE.

As the cytokines involved in MS pathology are explored for effects on oligodendroglial cells as well as immune cells, the reparative process of remyelination becomes appreciably more complex. Our data indicate IL-17A stimulates OPCs to exit the cell cycle and differentiate, activates the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, and induces chemokine and cytokine expression. Though IL-17A in an EAE or MS lesion may drive aberrant immune function, our data suggest it also promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation and may indeed encourage remyelination. Future studies analyzing combinations of proinflammatory cytokines will lend insight to the OPC response to the complex environment of the demyelinated lesion as well practical knowledge in designing remyelination strategies. Likewise, it will be necessary to define the direct effects of IL-17A on OPCs in animal models of demyelination particularly given that IL-17A modulation is the focus of MS therapeutic efforts.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: Myelin Repair Foundation (MRF).

We thank the MRF and collaborators as well as all members of the Miller laboratory for critical comments, experimental expertise, and editing.

Footnotes

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barres BA, Hart IK, Coles HS, Burne JF, Voyvodic JT, Richardson WD, Raff MC. Cell death and control of cell survival in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell. 1992;70:31–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90531-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Kijlstra A, Chen Y, Yang P. IL-17A stimulates the production of inflammatory mediators via Erk1/2, p38 MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and NF-kappaB pathways in ARPE-19 cells. Mol Vis. 2011;17:3072–3077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew LJ, King WC, Kennedy A, Gallo V. Interferon-gamma inhibits cell cycle exit in differentiating oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia. 2005;52:127–143. doi: 10.1002/glia.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codarri L, Gyulveszi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L, Suter T, Becher B. RORgammat drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuro-inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:560–567. doi: 10.1038/ni.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerford I, Harata-Lee Y, Bunting MD, Gregor C, Kara EE, McColl SR. A myriad of functions and complex regulation of the CCR7/CCL19/CCL21 chemokine axis in the adaptive immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:269–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JG, Kelly D, Rath EM, Baerwald KD, Suzuki K, Popko B. Targeted CNS expression of interferon-gamma in transgenic mice leads to hypo-myelination, reactive gliosis, and abnormal cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:354–370. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Sarma J, Ciric B, Marek R, Sadhukhan S, Caruso ML, Shafagh J, Fitzgerald DC, Shindler KS, Rostami A. Functional interleukin-17 receptor A is expressed in central nervous system glia and upregulated in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflamm. 2009;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elain G, Jeanneau K, Rutkowska A, Mir AK, Dev KK. The selective anti-IL17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab (AIN457) attenuates IL17A-induced levels of IL6 in human astrocytes. Glia. 2014;62:725–735. doi: 10.1002/glia.22637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe-Maricich SL, Karlo JC, Landreth GE, Miller RH. The ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:843–850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3239-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard CJ, Krakauer M, Bendtzen K, Lund H, Sellebjerg F, Nielsen CH. T helper cell type 1 (Th1), Th2 and Th17 responses to myelin basic protein and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Immunology. 2008;125:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter HH, Ibrahim SM, Koczan D, Kruse N, Weishaupt A, Toyka KV, Gold R. Therapeutic efficacy of IL-17 neutralization in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol. 2005;237:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövelmeyer N, Hao Z, Kranidioti K, Kassiotis G, Buch T, Frommer F, von Hoch L, Kramer D, Minichiello L, Kollias G, Lassmann H, Waisman A. Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes via Fas and TNF-R1 is a key event in the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:5875–5884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Liu C, Giltiay N, Qin H, Liu L, Qian W, Ransohoff RM, Bergmann C, Stohlman S, Tuohy VK, Li X. Astrocyte-restricted ablation of interleukin-17-induced Act1-mediated signaling ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 2010;32:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Wang C, Zepp J, Wu L, Sun K, Zhao J, Chandrasekharan U, DiCorleto PE, Trapp BD, Ransohoff RM, Li X. Act1 mediates IL-17-induced EAE pathogenesis selectively in NG2(+) glial cells. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1401–1408. doi: 10.1038/nn.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Li K, Zhu L, Kan Q, Yan Y, Kumar P, Xu H, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Inhibitory effect of IL-17 on neural stem cell proliferation and neural cell differentiation. BMC Immunol. 2013;14:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-14-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the response of myelinating oligodendrocytes to the immune cytokine interferon-gamma. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:603–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, Klonowski P, Austin A, Lad N, Kaminski N, Galli SJ, Oksenberg JR, Raine CS, Heller R, Steinman L. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2002;8:500–508. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Solanky M, Menonna J, Chapin J, Li W, Dowling P. Platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor-positive oligodendroglia are frequent in multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:776–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon RD, Piras G, Ida JA, Jr, Dubois-Dalcq M. A role for TGF-beta in oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1397–1407. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:888–898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintlia MK, Paintlia AS, Singh AK, Singh I. Synergistic activity of interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha enhances oxidative stress-mediated oligodendrocyte apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2011;116:508–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Cai Z, Rhodes PG. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on developing optic nerve oligodendrocytes in culture. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:226–234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA. Regulatory T-cells: Diverse phenotypes integral to immune homeostasis and suppression. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:186–204. doi: 10.1177/0192623311430693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi M, Sarnico I, Boroni F, Benarese M, Dreano M, Garotta G, Valerio A, Spano P. Prevention of neuron and oligodendrocyte degeneration by interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-6 receptor/IL-6 fusion protein in organotypic hippocampal slices. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AP, Rodgers JM, Goings GE, Miller SD. Characterization of oligodendroglial populations in mouse demyelinating disease using flow cytometry: Clues for MS pathogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JM, Miller SD. Cytokine control of inflammation and repair in the pathology of multiple sclerosis. Yale J Biol Med. 2012;85:447–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setzu A, Lathia JD, Zhao C, Wells K, Rao MS, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ. Inflammation stimulates myelination by transplanted oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Glia. 2006;54:297–303. doi: 10.1002/glia.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczucinski A, Losy J. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in multiple sclerosis. Potential targets for new therapies. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio A, Ferrario M, Dreano M, Garotta G, Spano P, Pizzi M. Soluble interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor/IL-6 fusion protein enhances in vitro differentiation of purified rat oligodendroglial lineage cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:602–615. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Arevalo-Martin A, Almazan G, Guaza C. Interleukin-1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:489–502. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernerey J, Macchi M, Magalon K, Cayre M, Durbec P. Ciliary neurotrophic factor controls progenitor migration during remyelination in the adult rodent brain. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3240–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2579-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolswijk G. Oligodendrocyte survival, loss and birth in lesions of chronic-stage multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 1):105–115. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]