Abstract

Background

There are several gender differences that may help explain the link between biology and symptoms in heart failure (HF).

Objective

The aim of this study was to examine gender-specific relationships between objective measures of HF severity and physical symptoms.

Methods

Detailed clinical data, including left ventricular ejection fraction and left ventricular internal end-diastolic diameter, and HF-specific physical symptoms were collected as part of a prospective cohort study. Gender interaction terms were tested in linear regression models of physical symptoms.

Results

The sample (101 women and 101 men) averaged 57 years of age and a majority of participants (60%) had class III/IV HF. Larger left ventricle size was associated with better physical symptoms for women and worse physical symptoms for men.

Conclusion

Decreased ventricular compliance may result in worse physical HF symptoms for women and dilation of the ventricle may be a greater progenitor of symptoms for men with HF.

Keywords: heart failure, gender, symptoms

Background

Adults living with heart failure (HF) experience significant physical symptoms like the hallmarks of dyspnea and fatigue.1 There is a limited association, however, between what patients experience as physical symptoms and what we can measure objectively about the severity of HF, including metrics of pressure, flow, contractility, exercise capacity and heart chamber geometry.2–7 Most of what we know about HF in general, and about the relationship between objective measures of heart function and symptoms in particular, is derived from studies predominated by men. There are, however, several important gender differences in HF. For example, women are more likely to have HF of non-ischemic etiology, and women have larger hearts by cardiothoracic ratio than men.8 Women are also diagnosed with HF later in life and are more likely than men to have HF with preserved ejection fraction.9 Thus, gender differences may help provide insight into the relationship between physical symptoms and the underlying pathophysiology of HF. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to examine how objective measures of heart function influence physical HF symptoms differently in women compared with men.

Methods

This paper involves a primary aim of a prospective cohort study on gender differences in HF symptoms that is described in detail elsewhere.10 Of particular importance is that detailed symptom and hemodynamic data were collected on 101 women and 101 men with symptomatic HF (i.e. New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification II-IV) during that study. Formal inclusion criteria included: 1) being willing and able to provide informed consent, 2) being 21 years of age or greater, 3) having the ability to read and comprehend 5th grade English, and 4) being on optimal HF treatment or having HF treatment optimized in the opinion of the treating cardiologist. Participants were ineligible if they had a diagnosis of major cognitive impairment in the medical record (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease), had received a heart transplant or long-term mechanical circulatory support, or were otherwise unable to complete the study requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants; the study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board. Data were collected between 2010 and 2013.

Measurement

Socio-demographic characteristics were assessed using a questionnaire that inquired about gender, age, marital/partnership status, ethnicity/race and employment. The presence of comorbid conditions were assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Clinical and HF-related treatment characteristics, including echocardiographic parameters (i.e. left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular internal end-diastolic diameter (LVIDd) in cm), and right heart catheterization parameters (i.e. pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) in mm/Hg, right atrial pressure (RAP) in mm/Hg, and cardiac index in L/min/m2 by the FICK equation), and laboratory values (i.e. hematocrit, sodium, and the ratio of blood urea nitrogen to creatinine) were collected during an in-depth review of participants’ electronic medical record. NYHA functional classification was assessed by the treating attending HF-specialty cardiologists on the same day as enrollment. Depression was measured with the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; a score of 10 or more is indicative of moderate or greater depression.11 Mild cognitive dysfunction was assessed, using the standard cutoff of less than 26 (range 0–30), on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)12 immediately following informed consent.

HF-specific physical symptoms were measured using the 18-item Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS).13 Participants are presented with a list of 18 common HF symptoms (e.g. “I could feel my heart beat get faster,” “I could not breathe if I lay down flat,” “I had a cough,” “I was tired,” “getting dressed made it hard to breathe,” and “I did not feel like eating”), and are asked to rate how bothersome the symptom has been on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Scores on the HFSPS were calculated by summing responses; higher values (range 0–90) indicate worse physical symptoms. The HFSPS Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 in this study.10

Statistical Analysis

Means, standard deviations and proportions were used to describe the sample. Student’s t- and χ2 tests were performed to compare characteristics between women and men with HF and identify clinical candidates for testing in gender interactions. Interaction terms were generated to quantify how each characteristic influenced physical symptoms differently between women and men and were then tested in linear regression models of physical symptoms (HFSPS score). Specifically, two-way interaction terms were calculated between gender (binary) and variables that were significantly different comparing women and men in this sample. Gender, the variable that was different by gender, and the interaction term were then tested as determinants of physical symptoms in linear regression models so that gender-specific intercepts and slopes could be calculated, and the significance of the gender interaction could be quantified. For graphic representation of gender-specific relationships, predicted margins were generated across observed ranges of LVIDd and presented in comparison with HFSPS and PCWP with adjustment for other model covariates that are known to influence heart chamber geometry (i.e. age and body mass index) and physical symptom burden (i.e. NYHA functional class), or were observed to be significantly different between women and men in this sample (i.e. hematocrit, ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology, and LVEF).

Results

The average age of the sample (n=202) was approximately 57 years, and the vast majority of female and male participants were Caucasian (Table 1). Women and men in this sample were generally similar with respect to socio-demographics, clinical HF and treatment characteristics, and physical symptoms. Notable exceptions were LVEF, which was greater in women compared with men and LVIDd, which was greater in men compared with women. Also, more women than men had HF of non-ischemic etiology, and, consistent with physiological differences, women had a lower hematocrit compared with men. LVEF, LVIDd, ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology, and hematocrit were then tested for differential influences on physical symptoms by self-identified gender.

Table 1.

Gender difference in clinical characteristics of heart failure

|

Patient Characteristics: mean±SD or n (%) |

Women (n=101) |

Men (n=101) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.6±14.6 | 57.1±12.0 | 0.789 |

| Caucasian | 85 (85%) | 87 (86.1%) | 0.512 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.3±7.7 | 31.1±7.0 | 0.461 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.3±1.6 | 2.3±1.3 | 0.950 |

| Moderate or greater depression | 27 (27.0%) | 25 (25.0%) | 0.840 |

| Mild Cognitive Dysfunction | 24 (30.0%) | 33 (36.3%) | 0.386 |

| Heart Failure Characteristics: | |||

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (%) | 30.3±13.1 | 26.9±11.6 | 0.046 |

| Left Ventricular Internal Diastolic Diameter | 5.6±1.0 | 6.5±1.0 | <0.001 |

| NYHA Functional Class: | |||

| Class II | 38 (37.6%) | 43 (42.6%) | |

| Class III | 59 (58.4%) | 54 (53.4%) | |

| Class IV | 4 (4.0%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0.441 |

| HF of Ischemic Etiology | 26 (26.0%) | 47 (46.5%) | 0.003 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 137.8±3.2 | 137.2±3.25 | 0.145 |

| Serum hematocrit (%) | 36.7±5.1 | 40.0±6.2 | <0.001 |

| Serum BUN-to-creatinine ratio (mg/dL:1) | 20.7±10.7 | 19.9±9.9 | 0.159 |

| Prescribed a β-blocker | 88 (87.1%) | 95 (94.1%) | 0.151 |

| Prescribed an ACE or ARB | 79 (78.2%) | 83 (82.2%) | 0.459 |

| Prescribed an aldosterone antagonist | 42 (41.6%) | 44 (43.6%) | 0.157 |

| Cardiac Index (L/min/m2) | 2.0±0.5 | 2.1±0.5 | 0.110 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mm/Hg) | 17.4±8.6 | 20.2±8.9 | 0.060 |

| Right atrial pressure (mm/Hg) | 8.9±5.2 | 10.8±6.1 | 0.052 |

| Symptoms: | |||

| Physical Symptoms (HFSPS) | 24.7±17.0 | 24.0±15.1 | 0.965 |

Note: p-value <0.05 based on t- or χ2 tests

Abbreviations ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker, BUN = blood urea nitrogen; HF = heart failure; HFSPS = Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale; NYHA = New York Heart Association; SD = standard deviation.

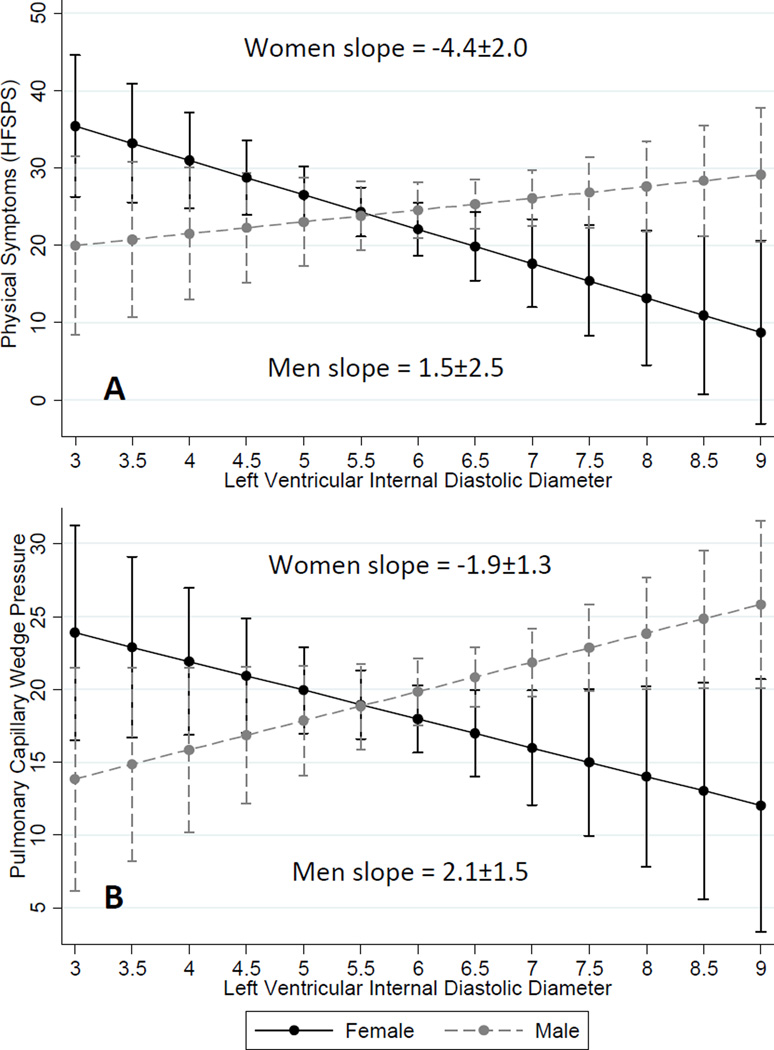

There were no gender interactions with the influence of LVEF (p=0.55), ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology (p=0.93), or hematocrit (p=0.07) on physical symptoms (data not shown). Controlling for age, body mass index, NYHA class, hematocrit, ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology and LVEF, the relationships between LVIDd and both physical symptoms and left-sided filling pressure were different comparing women and men. Specifically, larger left ventricle size was associated with better physical symptoms for women (β = −4.36±1.96, p=0.028) whereas larger left ventricular size was associated with worse physical symptoms for men (β = 1.51±2.47, p=0.019; interaction p=0.016) (Figure 1A). Larger left ventricle size was also associated with lower left-sided filling pressures for women (β = −1.94±1.32, p=0.016), whereas larger ventricle size was associated with higher left-sided filling pressures for men (β = 2.13±1.54, p=0.010; interaction p=0.010) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals for the influence of left ventricular internal diastolic diameter on (A) physical symptoms, and (B) pulmonary capillary wedge pressure are presented by gender. The slopes were significantly different comparing women. Larger ventricles were associated with fewer/less burdensome physical symptoms and lower left-sided filling pressure for women. In contrast, larger ventricles were associated with greater physical symptoms and higher left-sided filling pressure for men. Results shown are adjusted for age, body mass index, New York Heart Association functional class, hematocrit, ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology and left ventricular ejection fraction.

Abbreviations: HFSPS = heart failure somatic perception scale

Discussion

In this sample of 101 women and 101 men with symptomatic HF, there was no difference in the degree to which participants were bothered by physical symptoms by gender. There was, however, a gender-specific relationship between the diameter of the left ventricle at end-diastole and the severity of physical symptoms. Namely, larger ventricular diameter was associated with better physical symptoms for women and worse physical symptoms for men. In light of the paucity of prior insights into the relationship between objective measures of heart function and symptoms in HF,2–7 this is the first report of a gender-specific relationship between an objective metric of heart function and patients’ experiences with physical HF symptoms. By presenting additional data on gender-specific relationships between the diameter of the left ventricle and left-sided filling pressures, we also provide insight into a mechanism that may explain the gender difference in LVIDd and physical symptoms.

Understanding the biological underpinnings of symptoms in HF is important because the worsening of physical symptoms is the main reason patients seek urgent healthcare utilization.14 Physical symptoms are also the main drivers of health-related quality-of-life in HF15 and are integrally related with HF self-care behaviors.16 Despite several prior research reports, we know more about the general disconnect between symptoms and objective measures of HF than we know about how they are related. For example, Shah and colleagues2 found that invasive right heart catheterization parameters are not associated significantly with dyspnea. Rector et al.3 observed that several common objective measures of HF severity, including LVEF, blood pressure, and serum creatinine and hemoglobin, were not independently associated with physical HF symptoms. Meyers and group4 identified that symptoms of HF correlate poorly with peak oxygen uptake. Lewis and colleagues5 found that HRQOL (often used as a proxy for symptoms) does not differ significantly by LVEF. Bhardwaj et al.6 provided evidence that baseline values of amino-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide (Nt-proBNP), a biomarker of myocardial distention, were not related to HRQOL. Finally, Guglin and group7 recently concluded that there was no correlation between HF symptoms and multiple objective clinical factors including peak oxygen uptake, LVEF, Nt-proBNP and right heart catheterization parameters. By considering how objective measures of HF severity may influence the physical symptom of men and women differently, we have provided evidence of a gender-specific link between what the numbers can tell us about heart function and the patients’ experience with physical symptoms.

It has been described previously that women with HF have greater ventricular systolic function17 and smaller end-diastolic volumes18 compared to men with HF. Biological explanations for observed gender differences in heart size and function include differences in calcium handling, nitric oxide and natriuretic peptide activity, and the partial inhibition of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system and collagen synthesis by estrogen.19 Women are also known to have less left ventricular compliance compared with men,18 which may help explain the observed gender difference in LVIDd and physical symptoms. Ventricular stiffness during diastole, which is more common in women than men,20 may result in higher filling pressures (Figure 1B) and worse physical symptoms like dyspnea (Figure 1A) to a greater extent in women compared with men. Concomitant dilation of the left ventricle and elevated filling pressure may be a greater progenitor of physical HF symptoms for men in whom diastolic dysfunction is less prevalent.21

Although we are able to speculate and provide preliminary support as to the reasons why the diameter of the left ventricle influences physical symptoms differently in women than men, these and other mechanisms will need to be tested using experimental designs in future research. It is important to consider in clinical practice that there is no appreciable difference in the relationship between ischemic vs. non-ischemic etiology or LVEF and physical HF symptoms between women with men, despite these being well established gender differences. The greatest clinical implication from these findings is that a measure of heart function that is easily obtained from a routine echocardiogram (i.e. LVIDd) provides different information about women and men and their respective experiences with physical HF symptoms.

Conclusion

Decreased left ventricular compliance may result in worse physical HF symptoms for women and dilation of the ventricle may be a greater progenitor of physical symptoms for men. More research is needed to gain insight into the gender-specific pathophysiological underpinnings of HF symptoms.

What’s New?

Decreased left ventricular compliance is associated in worse physical symptoms for women with heart failure.

Greater dilation of the left ventricle is associated with worse physical symptoms for men with heart failure.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Office of Research on Women’s Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the Oregon Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health program (HD043488-08). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Contributor Information

Christopher S. Lee, Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing and Knight Cardiovascular Institute, Portland, OR, USA.

Shirin O. Hiatt, Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing, Portland, OR, USA.

Quin E. Denfeld, Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing, Portland, OR, USA.

Christopher V. Chien, Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cardiovascular Institute, Portland, OR, USA.

James O. Mudd, Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cardiovascular Institute, Portland, OR, USA.

Jill M. Gelow, Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cardiovascular Institute, Portland, OR, USA.

References

- 1.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, et al. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah MR, Hasselblad V, Stinnett SS, et al. Dissociation between hemodynamic changes and symptom improvement in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rector TS, Anand IS, Cohn JN. Relationships between clinical assessments and patients' perceptions of the effects of heart failure on their quality of life. J Card Fail. 2006;12:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers J, Zaheer N, Quaglietti S, Madhavan R, Froelicher V, Heidenreich P. Association of Functional and Health Status Measures in Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis EF, Lamas GA, O'Meara E, et al. Characterization of health-related quality of life in heart failure patients with preserved versus low ejection fraction in CHARM. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2007;9:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhardwaj A, Rehman SU, Mohammed AA, et al. Quality of life and chronic heart failure therapy guided by natriuretic peptides: results from the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) study. Am Heart J. 2012;164:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.08.015. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guglin M, Patel T, Darbinyan N. Symptoms in heart failure correlate poorly with objective haemodynamic parameters. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:1224–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghali JK, Krause-Steinrauf HJ, Adams KF, et al. Gender differences in advanced heart failure: insights from the BEST study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:2128–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stromberg A, Martensson J. Gender differences in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:7–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CS, Gelow JM, Denfeld QE, et al. Physical and Psychological Symptom Profiling and Event-Free Survival in Adults With Moderate to Advanced Heart Failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318285968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurgens CY. Somatic awareness, uncertainty, and delay in care-seeking in acute heart failure. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:74–86. doi: 10.1002/nur.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Szklo-Coxe M, et al. Symptom presentation in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:E73–E80. doi: 10.1002/clc.20627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, Ziegler C. Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CS, Gelow JM, Mudd JO, et al. Profiles of self-care management versus consulting behaviors in adults with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1474515113519188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, et al. Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayward CS, Kalnins WV, Kelly RP. Gender-related differences in left ventricular chamber function. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:340–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Brokat S, Tschope C. Role of gender in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gori M, Lam CS, Gupta DK, et al. Sex-specific cardiovascular structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scantlebury DC, Borlaug BA. Why are women more likely than men to develop heart failure with preserved ejection fraction? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:562–568. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32834b7faf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]