Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

How is the reproductive life plan (RLP) adopted in midwifery contraceptive counselling?

SUMMARY ANSWER

A majority of midwives adopted the RLP in their counselling, had predominantly positive experiences and considered it a feasible tool for promoting reproductive health.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The RLP is a health-promoting tool recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA for improving preconception health. It was recently used in a clinical setting in Sweden and was found to increase women's knowledge about fertility and to influence women's wishes to have their last child earlier in life.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

An exploratory mixed methods study among 68 midwives who provided contraceptive counselling in primary health care to at least 20 women each during the study period. Midwives received an introduction and materials for using the RLP in contraceptive counselling. Three months later, in the spring of 2014, they were invited to complete a questionnaire and participate in a focus group interview about their adoption of the RLP.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Data collection was through a questionnaire (n = 53 out of 68; participation rate 78%) and five focus group interviews (n = 22). Participants included both younger and older midwives with longer and shorter experiences of contraceptive counselling in public and private health care in one Swedish county. Quantitative data were analysed for differences between users and non-users, and qualitative data were analysed by qualitative content analysis to explore the midwives experiences and opinions of using the RLP.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

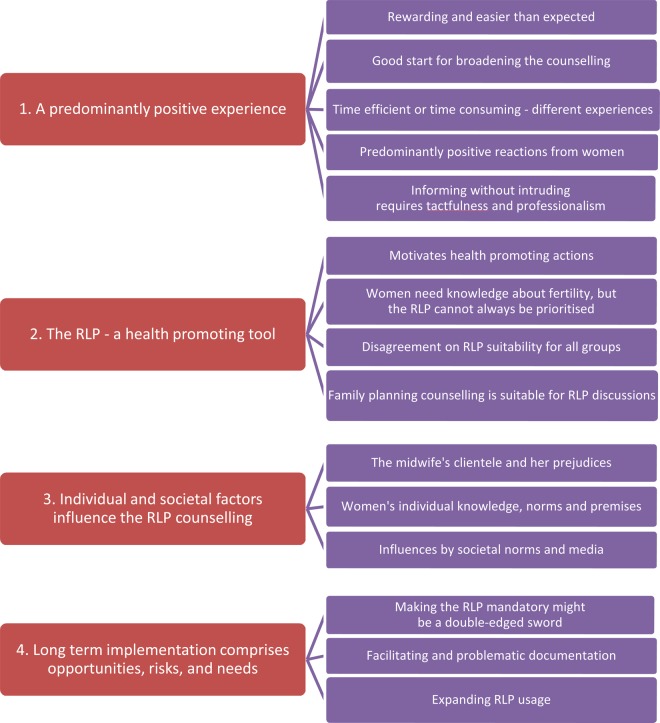

Sixty-eight per cent of midwives had used the RLP in their contraceptive counselling. Four categories emerged through the focus group interviews: (i) A predominantly positive experience; (ii) The RLP—a health-promoting tool; (iii) individual and societal factors influence the RLP counselling; and (4) long-term implementation comprises opportunities, risks and needs. The most common reason for not using the RLP was lack of information.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

There was general lack of experience of using the RLP with women from different cultural backgrounds, with non-Swedish speaking women and, when a partner was present. Due to the non-random sample, the limited knowledge about non-responders and a short follow-up period, results apply to short-term implementations and might not fully apply to long-term implementation.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The use of RLP in contraceptive counselling appears a feasible way of promoting reproductive health. Results from the USA and Sweden indicate it is a promising tool for midwives and other health professionals involved in reproductive counselling, which deserves to be explored in other nations.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

Grants were received from the Medical Faculty at Uppsala University and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health. There are no competing interests.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: family planning, contraceptive counselling, planned pregnancy, unplanned pregnancy, preconception care

Introduction

In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out that preconception care is relevant for all women of reproductive age. In high-income countries many women postpone childbearing until ages when their fecundity has decreased, whereas many women in low-income countries would benefit from delaying their first pregnancy and space subsequent pregnancies (WHO, 2013).

Preconception care is defined as a set of interventions that aim to identify and modify biomedical behavioural and social risk to a woman's health or pregnancy outcome through prevention and management (Moos et al., 2008). Since the most critical period for organ development occurs before many women even know they are pregnant, the first contact with antenatal care is often too late for advice about health-promoting changes in lifestyle.

The reproductive life plan (RLP) is a health-promoting tool recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for improving preconception health and decreasing unintended pregnancies and adverse pregnancy outcomes. CDC recommends health professionals to use the RLP to screen women and men for their intentions to have or not to have children in the short and long term and their risk of conceiving (CDC, 2006). The RLP has the potential for use in many areas of the world. The RLP consists of a set of non-normative questions on having or not having children (Moos, 2003), and aims to encourage women, men, and couples to reflect on their reproductive intentions and find strategies for successful family planning within the context of personal life goals and values (Moos et al., 2008). This includes having the desired number of children, avoiding unwanted pregnancies, and avoiding ill health that may threaten reproduction. Women with diabetes, hypertension and obesity were the target group when physicians at a Family Health Center in the USA tested the RLP concept. The intervention increased women's knowledge about reproductive health, especially among those with the lowest pre-counselling test scores and among women without children. The authors concluded that the RLP was a brief, cost-effective counselling tool for women with chronic diseases (Mittal et al., 2014). Another study from the USA among low-income, African-American and Hispanic females and males attending publicly funded clinics showed that more female than male primary care patients viewed questions about patients' reproductive plans as important (Dunlop et al., 2010). Also young healthy and well-educated women can benefit from a discussion about their RLP. In a RCT (Stern et al., 2013), the RLP concept was used in contraceptive counselling among female university students in Sweden, a group who tend to postpone childbearing until the age when their reproductive capacity has started to decrease and overestimate the chances of having a child with IVF (Lampic et al., 2006; Peterson et al. 2012). Women receiving RLP-based counselling increase their knowledge about fertility and intend to have their last child earlier in life, and nine out of ten state midwives should routinely discuss a RLP with their patients (Stern et al., 2013).

The adoption and implementation of new methods of prevention and health promotion in the health care system is a complex process. According to Fleuren et al. (2004), determinants that may impede (or facilitate) an innovation within a health care organization can be categorized into: characteristics of the socio-political context, characteristics of the organization, characteristics of the adopting person, characteristics of the innovation and characteristics of the innovation strategy.

Although the CDC has recommended the use of RLP in health care settings for many years, there is a lack of information on the adoption of the RLP in routine care and how health care personnel experience the RLP. The aim of this study was to investigate midwives' adoption of the RLP in contraceptive counselling in one county in Sweden.

Methods

Design

Exploratory mixed methods study among midwives in primary health care with questionnaires and focus group interviews.

Context and setting

Contraceptive counselling in Sweden is free of charge and mainly offered by nurse-midwives at antenatal/family planning clinics and youth clinics within the primary health care system. Midwives are responsible for healthy women and refer women with chronic diseases to gynaecologists. Until spring 2014, the national guidelines for contraceptive counselling focused solely on medical history and information about advantages and disadvantages of different contraceptive methods, but they now state that discussions about future reproduction can be included in the counselling (The Medical Products Agency, 2014).

The study was conducted in mid Sweden, in a county that covers both rural and urban areas. The county has 345 000 inhabitants, 14% are born outside Sweden, and the mean income is 215 000 SEK/year for women and 288 000 SEK/year for men. The education level is similar to the Swedish average, i.e. 27% of the population have postgraduate education. In spring 2014, the county had 68 midwives in 21 clinics with ∼20 000 visits/year for contraceptive counselling. All midwifery activities within the county's primary health care system are led by a co-ordinating midwife and a chief physician, who regularly convene educational meetings. The average time allocated for contraceptive counselling is 30 min and electronic medical records are used.

Procedure and participants

The co-ordinating midwife and the senior consultant in antenatal care supported the study. During an educational meeting in autumn 2013, the midwives were informed about the RLP and invited to participate in the study. All 51 midwives present were offered the opportunity to use the RLP in their counselling, and 36 midwives from 16 clinics volunteered. After the meeting, telephone contact was made with all clinics to invite additional midwives who had not attended the meeting. Out of the 68 midwives, 53 midwives volunteered to use the RLP. After receiving the RLP material, they were invited to a focus group interview (FGI) 3 months later.

Materials given to the midwives

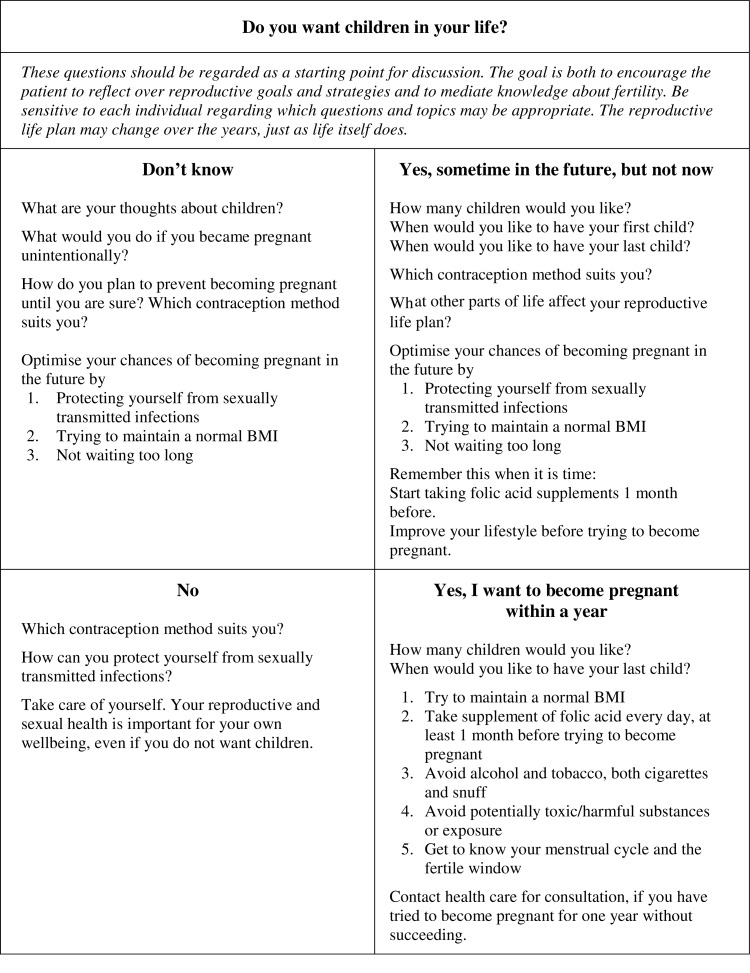

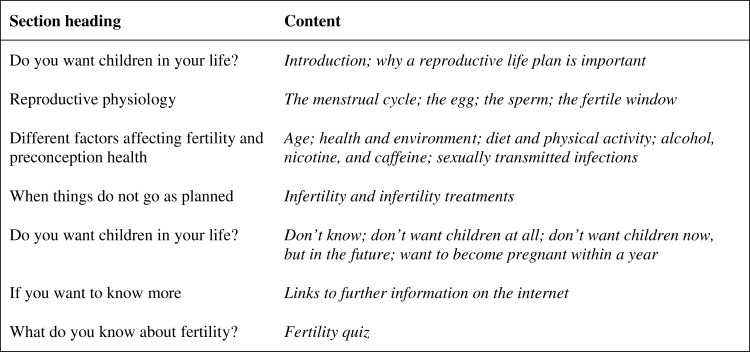

Participating midwives were provided with an RLP guide and a booklet. The RLP guide (Fig. 1) aims to assist the midwife in operationalizing the RLP in contraceptive counselling. The booklet was study-specific and consisted of 28 pocket-sized and colour printed pages in Swedish to be handed out during the counselling. An overview of the content of the booklet is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

The reproductive life plan (RLP) guide developed to assist the midwives during counselling.

Figure 2.

Overview of the content of the reproductive life plan (RLP) booklet developed to distribute to the women.

FGIs

Midwives who had experience of using RLP in contraceptive counselling were invited to participate in a FGI. Focus groups are used with the intention to better understand people's views of a subject. It creates a non-judgemental environment and can encourage participants to share their views without the need for consensus (Krueger and Casey, 2009). Five FGIs with 22 midwives were conducted in spring 2014 with a moderator and an observer. Each group consisted of 4–5 midwives and took place in conference rooms at the workplaces. A study-specific interview guide with open-ended questions was used, which covered the areas: (i) overall experiences, (ii) recall of specific experiences, (iii) the overall concept of the RLP, (iv) the materials (RLP-guide and booklet), (v) reactions from women, (vi) the future and (vii) the RLP for partners and/or for men. Both positive and negative aspects were probed, and when needed, follow-up questions were asked to clarify the statements. The interviews lasted on average 91 min (range 64–118 min), and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The midwives received a gift voucher for their participation.

Questionnaire

All midwives in the county (n = 68) received a study-specific questionnaire with questions about their background and overall experience and opinions on different aspects of the RLP. The background questions covered age, years of experience of contraceptive counselling, type of workplace (public/private health care provider; family planning/youth clinic), number of visits for contraceptive counselling/week, and number of visits where the RLP was used. Questions about the RLP were posed as Likert items on the overall concept (range of five scores on a continuum from very good to very bad), their general practical experience (very positive—very negative), the booklet (very useful—very unusable), the RLP-guide (very useful—very unusable) and intended RLP usage in the future (always—never).

Participants who had not used the RLP were asked to state their reasons, through the following alternatives: not received information about RLP; did not have time/energy to engage in a new project; the information was insufficient; do not like the idea of the RLP in contraceptive counselling; time constraints/special circumstances at the clinic; sick leave/parental leave; or other. Midwives participating in the FGI completed the questionnaire before the interview, and the remainder of the midwives received a postal questionnaire at their workplace. One reminder was sent to non-responders after 2 weeks. The response rate was 78% (n = 53).

Data analysis

The interviews were analysed with qualitative content analysis, as described by Burnard et al. (2008). To obtain an overall picture of the data, transcripts were read several times. In the open coding, notes were made in the margins to summarize the relevant data according to the aim of exploring midwives experiences and opinions of the RLP. After deleting duplications, all initial codes were collated and compiled into subcategories and finally into categories. The analytic process involves back and forth movements to the text, and categories were traced back in the transcripts to ensure validity. The initial analysis was carried out by three of the authors and was validated by two of the others. Examples of the analytical process are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Example of the analytical process in a study of how the reproductive life plan (RLP) is adopted in contraceptive counselling by midwives.

| Interview transcript | Initial coding | Sub-category | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exciting to explore women's knowledge | 1.1. A rewarding way of working and easier than expected | 1. The experience of the RLP was predominantly positive |

|

Need to begin earlier | 4.3. Expanding the usage to other target groups, arenas, and professions | 4. Long-term implementation comprises opportunities, risks and needs |

FGI, focus group interview.

The questionnaire data were entered and analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 20, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Midwives who used the RLP and midwives who had not used the RLP were compared regarding background variables (age, years of experience of contraceptive counselling, workplace, type of clinic, number of visits for contraceptive counselling/week) with Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous and ordinal variables and Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (2012/101). Written consent was obtained when participants provided some demographic characteristics before the interview started.

Results

Adoption of the RLP in contraceptive counselling

Initially, 78% (n = 53) of all midwives in the county agreed to use the RLP in their contraceptive counselling, and 68% (n = 36) of all midwives responding to the questionnaire had used RLP in their contraceptive counselling. The characteristics of the midwives are presented in Table II. Midwives who had not used the RLP had fewer visits for contraceptive counselling per week than midwives who had used it. A higher proportion of non-responders were employed by a private health care provider than responders. The most common reason for not using the RLP was the midwife had not received any information about the RLP (n = 8). No midwife stated they did not like the idea of RLP in contraceptive counselling. The results regarding the general experience of the RLP among the midwives who had used it are presented in Table III.

Table II.

Characteristics of midwives responding to the questionnaire, n = 53.

| Characteristics | Midwives who used the RLP n = 36 |

Midwives who did not use the RLP n = 17 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD (range) | 52 ± 10 (31–65) | 48 ± 10 (34–65) | 0.116a |

| Years of experience of contraceptive counselling, mean ± SD (range) | 13 ± 11 (1–40) | 9 ± 9 (0.5–30) | 0.222a |

| Workplace | 0.130b | ||

| Public health care provider | 30 | 11 | |

| Private health care provider | 6 | 6 | |

| Type of clinic | 0.882b | ||

| Midwifery clinic | 25 | 12 | |

| Both midwifery and youth clinic | 11 | 5 | |

| Number of visits for contraceptive counselling/week, mean ± SD (range) | 15 ± 7 (6–30) | 11 ± 6 (3–25) | 0.024a |

aP-value for comparison between the two groups, analysed with Mann–Whitney U-test.

bP-value for comparison between the two groups, analysed with Pearson's χ2 test.

Table III.

General experience of the RLP among midwives who used the RLP (n = 36).

| N | |

|---|---|

| The very idea of the RLP is… | |

| Very or rather good | 35 |

| Neither good nor bad | 1 |

| Very or rather bad | 0 |

| Missing | 0 |

| My general experiences of RLP have been… | |

| Very or rather positive | 33 |

| Neither positive nor negative | 3 |

| Very or rather negative | 0 |

| Missing | 0 |

| The booklet to the patients was… | |

| Very or rather useful | 33 |

| Neither useful nor useless | 2 |

| Very or rather useless | 0 |

| Missing | 1 |

| The RLP-guide to the midwives was… | |

| Very or rather useful | 32 |

| Neither useful nor useless | 4 |

| Very or rather useless | 0 |

| Missing | 0 |

| In the future, I will use the RLP… | |

| Always/often | 19 |

| Sometimes | 16 |

| Seldom/never | 0 |

| Missing | 1 |

Experiences and opinions of the RLP according to the FGIs

The characteristics of the midwives in the FGI did not differ from the other midwives who had used RLP, except that a higher proportion in the FGI worked for private health care providers. Midwives who participated in the FGI were also more positive regarding their general experience of the RLP than midwives who did not participate in the FGI.

During the FGI, the questions most often led to a lively discussion, where the midwives often interrupted each other and expressed both agreement and disagreement. In some groups, a few participants dominated the discussion, but all midwives made their voices heard.

To introduce the RLP into the counselling, some midwives used the direct question ‘do you want children in your life?’, whereas others wove it into the conversation. Some told the women about the study as a reason for raising the topic, some asked for the women's permission to discuss the topic and some used questions about fertility to approach the topic. The RLP-guide was considered a good and relevant support for the discussion and was often placed nearby to serve as a reminder. Although the RLP-guide was seldom used literally, some midwives used it together with the patient and some had not used it at all. Some midwives used the booklet during counselling, for example as a starting point for discussion, by going through the information together with the woman or by using the fertility quiz. Some midwives gave reading instructions and others just handed it out. The booklet was generally considered an asset for the midwife, particularly when time was restricted and as an accessible information resource for the woman.

Four categories emerged from the FGIs about the midwives experiences and opinions of working with the RLP (Fig. 3), and selected quotations from the midwives appear below.

1. A predominantly positive experience

Figure 3.

Overview of the results from the qualitative analysis.

The midwives had various degrees of experience with the RLP. There was general lack of experience of using the RLP with women from different cultural backgrounds, with non-Swedish speaking women, when a partner was present, and with men alone. However, when used, the experience was predominantly positive.

1.1. Rewarding and easier than expected

The midwives expressed the RLP gave the discussion a different angle when actively posing the question about intentions of having children. They also experienced the RLP as interesting, exciting, and fun, and that it refreshed and updated their knowledge. Initially, they were concerned it would be more complicated and difficult to get started, but found it easier the more they used it.

There is a difference, now I take this up… otherwise you would just talk about it if the patient has taken up the issue of children. [FGI4]

1.2. Good start for broadening the counselling

Both the RLP-guide and the booklet were considered good conversation starters. Questions were easy to pose, and helped them raise the topic with specific individuals. The RLP was experienced as a structured and systematic way of working that broadened the counselling, gave it a context, worked as an eye-opener and made the women think about their plans. Consequently, there was a more reflective interaction. However, there was a risk of being stuck with detailed questions from the woman, for example about the kind of vegetables containing the highest concentration of folic acid.

You get it in a context, such as why do we talk about BMI, why do we talk about smoking… that you see the bigger picture [FGI3]

1.3. Time efficient or time consuming: different experiences

The midwives considered other competing tasks, such as antenatal care and cervical cancer screening, a hindrance to using the RLP, but had diverse experiences of time spent on the RLP. Some expressed it took extra time and only raised the questions when they felt they had time for it. Others described the RLP as less time consuming than expected, and some stated it to be time efficient or even take less time than standard care. The RLP was experienced as less time consuming and more efficient than other routine questions.

Although I am surprised at how little extra time it took [FGI3]

1.4. Predominantly positive reactions from women

The midwives considered women reacted more positively than they had expected; most women were interested and were happy to be asked. The midwives experienced a need for, and wish, to discuss this topic, and that most women were receptive to the information. Still, some women were not interested and one even expressed that it was a rude question and her own business. Even though many women had not reflected over their plans, the midwives were surprised by individual women's answers and that many had a clear vision. The midwives described that many women had unrealistic plans and wanted to keep all options open and many women were surprised when they realized how little they knew about reproduction.

I think some light up… they are actually glad that you take this up… [FGI4]

1.5. Informing without intruding requires tactfulness and professionalism

The midwives felt that the RLP was disarming; it does not presuppose anything about the woman, but enables the midwife to provide information without intruding. Still, it was discussed whether it was appropriate to pose these questions; if a woman's plan for childbearing is not after all a private matter. The midwives emphasized the importance of tactfulness in adapting the information to the individual woman and the particular conversation. It was also considered important to be professional and non-judgmental, and to pose the questions with interest rather than indifference. Some stated that just asking the questions could never be harmful, whereas others were concerned about the risk of applying pressure and initiating unwanted processes. Some groups were perceived as more difficult to counsel in a good manner than others were, such as very young women and single women.

There is a risk that you ask the question wrong… that it is not a natural question… so… I think the patient feels you are interested… if you ask the question honestly [FGI4]

2. The RLP: a health-promoting tool

The midwives considered the RLP as a health-promoting concept that gives additional value to the contraceptive counselling.

I think the conversation is better, there is more substance to the conversation about contraception in some way [FGI1]

2.1. Motivates health-promoting actions

The RLP was seen as a way to motivate and trigger health-promoting actions, such as protection against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies or improvement in life style habits.

Even those of a young age start to think about things in a different way, I think… ‘perhaps I should take care of myself, not just get the p-pill and then come in every other week for a Chlamydia test. What I do can lead to other things'. [FGI3]

2.2. Women need knowledge about fertility, but the RLP cannot always be prioritized

It was stated that women need and have the right to knowledge about fertility and this was important both for preventing unwanted pregnancies and for optimizing preconception health. Some midwives stated the RLP was prioritized over other routine questions, whereas other midwives considered areas such as medical anamneses and screening for domestic violence should have higher priority.

I think it is a woman's right to find out about fertility and how you can affect it and control it [FGI5]

2.3. Disagreement on RLP suitability for all groups

A general opinion was that the RLP was suitable for all kinds of women; however, after discussing this in more detail, disagreement arose concerning a wide range of groups. For example, some midwives considered it was an extra important concept for adolescents, whereas others considered it unsuitable for this group. Other groups that were discussed included older women, childless women, women who already had children, single women, women accompanied by their partners, women with intellectual disability, women in the rural areas, women with medical risk factors, and women with other cultural backgrounds and/or languages.

I think… we have some that are… less gifted… who want children, but it may not be appropriate for them to have children and then it may be unsuitable to ask the questions [FGI4]

2.4. Family planning counselling is suitable for RLP discussions

The RLP was considered to fall within the scope of the midwives work; there was only disagreement on whether or not it was the midwife's responsibility to discuss the impact of certain drugs on reproduction. Some midwives had discussed RLP-like matters before, although not in a structured way, whereas, for others, it was a new question. The midwife was found to be the right person to discuss the RLP, as a neutral authority who was considered a safe and trusted person to talk to, and to whom all kinds of women came. The RLP was considered appropriate for all kinds of visits at the midwifery clinics, although less suitable for a woman's first visit for contraceptive counselling, as the more extensive medical inquiry and comprehensive information about different kinds of contraceptives usually takes more time.

Yes, I think there is someone that you should get this information from, and that is definitely the midwife [FGI5]

3. Individual and societal factors influence the RLP counselling

Based on previous experiences, the midwives believed many factors could influence the RLP counselling.

3.1. The midwife's clientele and her prejudices

The midwives expressed their clientele determines who they can reach; for example women born abroad seldom visit the midwife for contraceptive counselling and partners are rarely present, however, women with medical risk factors are more common. The midwives also expressed they had prejudices towards different groups, for example youths and certain socioeconomic groups, and this might affect who they approached with questions regarding childbearing.

I find it a bit difficult to ask it as a direct question… my own prejudices a 21 year old girl who does not have a steady partner, so it feels a bit awkward… should I ask about it, should I ask a direct question if she hasn't given any sign that she wants to talk about it herself [FGI2]

3.2. Women's knowledge, norms and premises

The midwives described a great variety of norms and premises for childbearing among the women they meet, depending on their background. Women were also described as having varying knowledge about reproduction, most often less than expected by the midwives. For some women, the lack of knowledge creates unnecessary anxiety, whereas others have a carefree attitude.

We think it is so strange that they do not know, but it is really like that… you can keep track of so many other things in the world as mobile phones are updated on everything, but we know very little about how the body works… [FGI4]

3.3. Influences by societal norms and media

The midwives acknowledged that societal norms highly influence individuals' decisions regarding childbearing: women are generally expected to have children, and the norm is to postpone parenthood. Media was also described as influential, picturing celebrities successfully having children at a very advanced age without mentioning the time, costs, and suffering it might have taken.

Adolescence is getting longer and you begin to talk about young adults up to the age of 25 or 30 years. Then it's late … before you are an adult and have children [FGI3]

4. Long-term implementation comprises opportunities, risks and needs

Some midwives stated they had all the information they needed to use the RLP, whereas others believed they needed more knowledge and wanted more information before starting to use the RLP. It was suggested that more in-depth preparation for all midwives through role-plays and group discussions could have facilitated the introduction of the RLP. Suggestions for the future included incorporating the concept into midwifery education, translating the booklet into different languages, and developing internet resources that midwives could refer to for further information.

It is obvious that we should continue, that's what it feels like. This is fun and exciting [FGI1]

4.1. Making the RLP mandatory might be a double-edged sword

The midwives considered it would be advantageous if all midwives used the RLP, but stated that some kind of guideline needed to be developed to make this happen. However, there was some concern about making the RLP mandatory, as this could mean the RLP lost its attraction and that the questions would be posed in an indifferent way.

For everyone to do this, then something needs to come from higher up… now we are going to start with this and everyone will do it … otherwise it will just be for those that think it is… fun [FGI4]

This is fun to work with and great to work with, but if it comes as a must… then it would not be as much fun anymore. [FGI3]

4.2. Facilitating and problematic documentation

The midwives wanted an easy and quick way to register the RLP counselling in the records, but disagreed on whether the woman's individual RLP should be included in the documentation. If the woman's answers were noted, it would create a possibility for follow-up and avoid what they felt would be an unprofessional repetition of the question. On the other hand, it was perceived as unethical to document plans that could change over time and it could also lead to the midwife not daring to ask again. It was also suggested that the woman ought to decide for herself whether her RLP should be documented or not.

If you don't document it anywhere then you have to start afresh each time and then it might well be perceived as a bit, I don't know…

Repetitive

Unprofessional somehow… a bit repetitive [FGI1]

4.3. Expanding RLP usage

The midwives considered the RLP needs to follow the women from an early age through their fertile life, and that arenas other than midwifery should be involved to reach all women. It was suggested the concept would also be appropriate for men and that the booklet could be distributed on its own, without the counselling to reach a broader target group. Schools, youth clinics, student health centres and primary health care centres were suggested as possible arenas. Other professionals such as teachers, school nurses, health nurses, doctors, dieticians, counsellors and sexologists might also benefit from using the RLP.

Not everyone comes to us! So there must certainly also be another forum. [FGI1]

Discussion

The RLP is potentially a relevant tool for reproductive counselling globally. This study provided the first exploration of its adoption in clinical practice, for which Swedish midwifery care served as an exemplary setting. A majority of the midwives approached adopted the RLP in their contraceptive counselling and their experience of the RLP was predominantly positive. They considered the RLP as a health-promoting tool suitable for, but not limited to, contraceptive counselling. The most common reasons for not using the RLP were related to practical matters, such as lack of information, rather than the concept itself.

Both qualitative and quantitative data were used to gain a deeper understanding of the adoption of the RLP. The study was conducted among midwives, as they are the main providers of contraceptive counselling in Sweden. The survey response rate was high, but it is possible non-responders had different reasons for not using the RLP or different experiences and opinions of using it. One large private clinic dropped out due to heavy workload and those midwives did not return the questionnaire. Except for type of workplace, we have no further information about those who did not respond to the questionnaire.

The follow-up was conducted 3 months after the midwives received the RLP material. Although a longer test period might have generated a broader range of experiences and slightly different opinions about the RLP, it was considered valuable to capture the midwives' first impressions and identify any immediate potential hindrances; therefore, a 3-month test period was chosen. A registered nurse and two registered midwives, both known to the midwives but not acquaintances or colleagues, conducted the FGI with the midwives. To help create an open discussion climate, it was emphasized that the interview did not aim to evaluate the midwives as professionals, but their experiences and opinions about the RLP, and that positive and negative aspects were equally important. The mixed method of the survey and the FGIs was a strength and a way of confirming the findings through triangulation. We undertook several measures to ensure trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). The method and the analytical process are thoroughly described and the findings are supported with illuminating citations to ensure credibility. Dependability refers to the stability over time and over conditions, and requires further studies. To ensure confirmability and decrease the risk of bias or distortion during the analytical process, three of the authors did the initial analysis jointly and validated the findings with the other authors. The research group thus worked both individually and together to achieve rigour and consensus. Although limited to one county in mid Sweden, the participants had mixed backgrounds; the midwives were both older and younger with varying experience of contraceptive counselling and worked in both rural and urban areas. Therefore, the findings are considered transferable to other Swedish counties. We expect findings from this study could also be of global interest. A specially designed booklet, such as the one we developed for this study, or an educational hand-out (Files et al., 2011), is easy to adapt to other populations and can be used by health care providers with limited time for consultations (Dunlop et al., 2007). However, the implementation of the RLP concept and the effect needs to be confirmed through further studies and we are now expanding our project to other parts in Sweden. Similar RLP studies are planned in the UK and in Denmark within the PrePreg Research Network (Shawe et al., 2014); a group of scientists with a research programme for better understanding of factors affecting preconception health and care. Shawe et al. (2014) have in a review shown that there are variations in preconception recommendations across Europe.

The participants believed the use of the RLP fell within their scope of work, which is consistent with the newly updated guidelines for contraceptive counselling that stipulates inclusion of discussions about future reproduction (The Medical Products Agency, 2014). They also experienced the use of the RLP as a more structured and systematic way of working. CDC has recently recommended the use of RLP when women attend family planning services for pregnancy testing (Gavin et al., 2014). There is no consensus of the most effective way to provide contraceptive counselling (Lopez et al., 2013) and Swedish midwives use a variety of strategies and self-made models (Wätterbjörk et al., 2011). The midwives also believed women need knowledge about fertility and considered that the RLP broadened the counselling. Furthermore, the women appreciated the counselling, which supported findings from another study (Stern et al., 2013), in which women receiving RLP-based information considered the information new to them and thought about reproduction in a different way afterwards.

Although generally positive towards the RLP, the midwives in the FGI discussed several potential barriers for adopting it. In accordance with the categorization of Fleuren et al. (2004), these barriers were related to characteristics of the organization (lack of time, competing tasks, not being able to reach certain groups), characteristics of the user (importance of tactfulness and professionalism), characteristics of the innovation (difficulty approaching certain groups) and characteristics of the innovation strategy (initial hesitation, making RLP mandatory, documentation). The multifactorial characteristics of potential barriers have also been identified in an American context regarding implementation of preconception care in general (Coffey and Shorten, 2013).

We consider the RLP in contraceptive counselling could contribute to improved reproductive public health. Depending on the woman's family planning intentions and the context/culture in which she is living, the counsellor can lead the discussion in different directions from birth control to preconception counselling, or a mixture of both. Teachable moment has been used to describe naturally occurring health events thought to motivate individuals to spontaneously adopt risk-reducing health behaviours (Hochbaum, 1958). The RLP thereby holds great potential for both preventing unplanned pregnancies and improving preconception health. However, the health care professional delivering the counselling plays a key role and is crucial for the successful implementation of the RLP in routine care. Therefore, it is important to address the potential barriers highlighted by the participants. This could include improving the information about the content of the brochure and potential benefits of using RLP in contraceptive counselling. Enhancing the training given to the midwives, offering continuous support and performing evaluations are other suggestions. An important topic would be communication methodology, for instance information on how to approach certain groups and how to approach the topic with tactfulness and professionalism. Motivational interviewing could be useful but remains to be further tested in reproductive health promotion (Rollnick and Miller, 1995). Even so, the most essential aspect for successful implementation is for the RLP to be regarded as advantageous and useful by the users, which was the case among the participants in this study.

As suggested in the FGIs, the concept should not be limited to midwives: expansion into other health care professions and arenas would enable RLP to reach a larger population. Also, web-based resources could reach women and men outside of the health care system, and provide health care personnel with easy to find and updated information.

Future directions for research will be to study the implementation process in routine care through different health care providers and investigate the effect of the RLP in contraceptive counselling among a general population of women in various settings. More knowledge is required on how the RLP is perceived by different groups, such as women of different ages, and how counselling can be more effective in reaching less accessible groups of women. Future studies will also be needed on the feasibility and effect of the RLP in other arenas, such as school health and post-natal care services, and for other target groups.

Conclusions

Swedish midwives generally adopted the RLP in contraceptive counselling, had predominantly positive experiences of the RLP and considered it a feasible tool for promoting reproductive health. This underlines the promise of the RLP, and the relevance of exploring the use of RLP by other health professionals and in nations other than the USA and Sweden.

Authors' roles

J.S., M.B., T.T. and M.L. planned and designed the study. J.S., M.B., T.T., M.L., L.A. and B.S. contributed to the acquisition of data. J.S., M.B., M.G., T.T. and M.L. analysed the data. J.S. provided a draft manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

Grants were received from the Medical Faculty at Uppsala University and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (3297 EUR). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Medical Faculty at Uppsala University.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all midwives who participated in the study.

References

- Burnard P, Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br Dent J 2008;204:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States: a report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey K, Shorten A. The challenge of preconception counselling: using reproductive life planning in primary care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2013;26:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop AL, Jack B, Frey K. National recommendations for preconception care: the essential role of the family physician. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop AL, Logue KM, Miranda MC, Narayan DA. Integrating reproductive planning with primary health care: an exploration among low-income, minority women and men. Sex Reprod Healthc 2010;1:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Files JA, Frey KA, David PS, Hunt KS, Noble BN, Mayer AP. Developing a reproductive life plan. J Midwifery Womens Health 2011;56:468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleuren M, Wiefferink K, Paulussen T. Determinants of innovation within health care organizations—literature review and Delphi study. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16:107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, Curtis K, Glass E, Godfrey E, Marcell A, Mautone-Smith N, Pazol K, Tepper N, et al. Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum GM. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Sociopsychological Study. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 4th edn Thousands Oakes, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lampic C, Skoog Svanberg A, Karlström P, Tydén T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum Reprod 2006;21:558–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez LM, Steiner M, Grimes DA, Hilgenberg D, Schulz KF. Strategies for communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;30:4:CD006964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Products Agency. Antikonception—behandlingsrekommendation. Information från Läkemedelsverket. 2014;25:14–28 (in Swedish). Recommendation for anticonception. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal P, Dandekar A, Hessler D. Use of a modified reproductive life plan to improve awareness of preconception health in women with chronic disease. Perm J 2014;18:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos MK. Unintended pregnancies—a call for nursing action. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2003;28:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos MK, Dunlop AL, Jack BW, Nelson L, Coonrod DV, Long R, Boggess K, Gardiner PM. Healthier women, healthier reproductive outcomes: recommendations for the routine care of all women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;08:S280–S289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Tucker L, Lampic C. Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1375–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother 1995;23:325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawe J, Delbaere I, Ekstrand M, Hegaard HK, Larsson M, Mastroiacovo P, Stern J, Steegers E, Stephenson J, Tydén T. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six European countries: Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2014;30:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern J, Larsson M, Kristiansson P, Tydén T. Introducing reproductive live plan-based information in contraceptive counselling: an RCT. Hum Reprod 2013;28:2450–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wätterbjörk I, Häggström-Nordin E, Hägglund D. Provider strategies for contraceptive counselling among Swedish midwives. BJM 2011;5:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Meeting to Develop a Global Consensus on Preconception Care to Reduce Maternal and Childhood Mortality and Morbidity 2013.