Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

How comprehensive is the recently published European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE)/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) classification system of female genital anomalies?

SUMMARY ANSWER

The ESHRE/ESGE classification provides a comprehensive description and categorization of almost all of the currently known anomalies that could not be classified properly with the American Fertility Society (AFS) system.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Until now, the more accepted classification system, namely that of the AFS, is associated with serious limitations in effective categorization of female genital anomalies. Many cases published in the literature could not be properly classified using the AFS system, yet a clear and accurate classification is a prerequisite for treatment.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE AND DURATION

The CONUTA (CONgenital UTerine Anomalies) ESHRE/ESGE group conducted a systematic review of the literature to examine if those types of anomalies that could not be properly classified with the AFS system could be effectively classified with the use of the new ESHRE/ESGE system. An electronic literature search through Medline, Embase and Cochrane library was carried out from January 1988 to January 2014. Three participants independently screened, selected articles of potential interest and finally extracted data from all the included studies. Any disagreement was discussed and resolved after consultation with a fourth reviewer and the results were assessed independently and approved by all members of the CONUTA group.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Among the 143 articles assessed in detail, 120 were finally selected reporting 140 cases that could not properly fit into a specific class of the AFS system. Those 140 cases were clustered in 39 different types of anomalies.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

The congenital anomaly involved a single organ in 12 (30.8%) out of the 39 types of anomalies, while multiple organs and/or segments of Müllerian ducts (complex anomaly) were involved in 27 (69.2%) types. Uterus was the organ most frequently involved (30/39: 76.9%), followed by cervix (26/39: 66.7%) and vagina (23/39: 59%). In all 39 types, the ESHRE/ESGE classification system provided a comprehensive description of each single or complex anomaly. A precise categorization was reached in 38 out of 39 types studied. Only one case of a bizarre uterine anomaly, with no clear embryological defect, could not be categorized and thus was placed in Class 6 (un-classified) of the ESHRE/ESGE system.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The review of the literature was thorough but we cannot rule out the possibility that other defects exist which will also require testing in the new ESHRE/ESGE system. These anomalies, however, must be rare.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The comprehensiveness of the ESHRE/ESGE classification adds objective scientific validity to its use. This may, therefore, promote its further dissemination and acceptance, which will have a positive outcome in clinical care and research.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

None.

Keywords: ESHRE/ESGE system, Müllerian anomalies, complex anomaly, comprehensiveness, classification

Introduction

Congenital malformations of the female genital tract consist of a group of miscellaneous deviations from normal anatomy. Although certain types of congenital malformation are the result of a clear disturbance in one stage of embryologic development, others are the result of disturbances in more than one stage of normal formation. The combination of malformations, which occur at different stages of development, seems to be the reason for the extremely wide anatomical variations and the large number of combinations of congenital malformation of the female genital tract observed (Grimbizis and Campo, 2010).

At time of writing, three systems have been proposed for the classification of female genital tract anomalies: that of the American Fertility Society (AFS), now the American Society of Reproductive Medicine system (AFS, 1988); the embryological–clinical classification system of genito-urinary malformations (Acién et al., 2004a; Acién and Acién, 2011); and the Vagina, Cervix, Uterus, Adnexa and associated Malformations (VCUAM) system, based on the Tumor, Nodes, Metastases principle in oncology (Oppelt et al., 2005).

The AFS classification system has been successfully adopted as the main classification system for almost two decades as it is simple, user-friendly and clear enough. However this system has several limitations in terms of effective categorization of the anomalies; many congenital anomalies could not be classified in the main categories and sub-categories of the AFS system, the borders of arcuate and septate uterus are not clear, AFS class I groups an excessive number of anomalies with totally different clinical presentation, and obstructive anomalies are not adequately represented. A systematic re-evaluation of the all the existing proposals (i.e. the AFS, the embryological clinical and the VCUAM systems) has been already published, underlying the need for a new and updated clinical classification system (Grimbizis and Campo, 2010).

The new European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE)/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) classification system of female genital anomalies is designed mainly for clinical orientation and it is based on the anatomy of the female genital tract (Grimbizis et al., 2013a,b). This classification system seems to overcome the limits of the previous attempts; however its clinical value still needs to be proved (Grimbizis et al., 2013a,b).

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the effectiveness and the comprehensiveness of the ESHRE/ESGE classification system focusing on those cases reported in the literature that could not be properly classified by the AFS system.

Materials and Methods

Literature search methodology, study selection and data extraction

We conducted an electronic literature search through Medline, EMBASE and Cochrane library from January 1988 (i.e. date of publication of AFS classification system) to January 2014 using MESH combinations of the following key words: ‘female genital tract anomaly’, ‘müllerian anomaly’, ‘müllerian duct anomaly’, ‘uterine anomaly’ ‘cervical anomaly’, ‘vaginal anomaly’ AND ‘categorization’, ‘classification’, ‘diagnosis’, ‘case report’, ‘exceptional case’, ‘rare anomaly’, ‘rare case’. Only scientific publications in English, Italian, French and Spanish were included. The study was designed and approved by the Scientific Committee (SC) of the CONUTA Working Group.

Three participants in the systematic review (A.D.S.S., C.C., M.S.) screened independently titles and abstracts of studies obtained by the search strategy. All cross-references were hand-searched, as were relevant conference abstracts. All types of studies were selected and each potentially relevant study was obtained in full text and assessed for inclusion independently by the three authors.

The three authors independently extracted data from all included studies. The results were compared and any disagreement was discussed and resolved by consensus after consultation with a fourth reviewer (G.G.). Finally, the results were assessed independently and approved by all the members of the SC of the CONUTA Group.

Outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the classifiability of all the identified anomalies reported as exceptional and ‘not classifiable’ according to the AFS classification system, into a specific class and/or subclass of the novel ESHRE/ESGE classification system.

Results

Search results

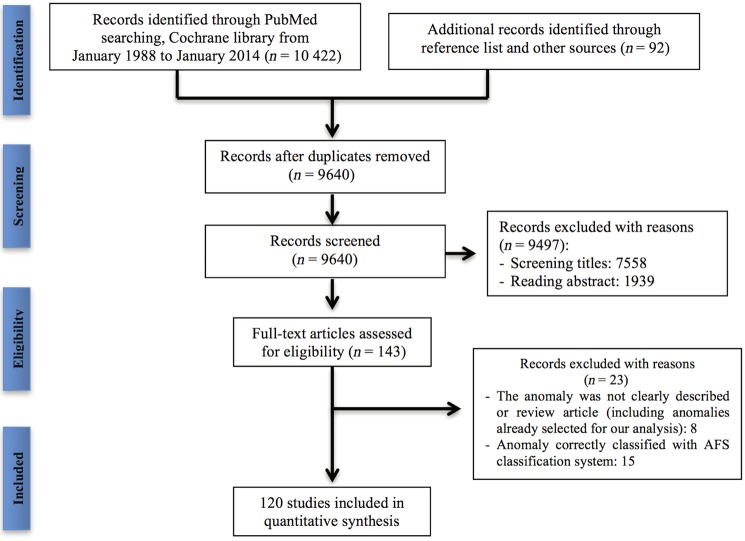

Of the 10 514 related papers, 874 were removed as duplicated articles. A total of 9497 were excluded after reading the abstracts or screening titles (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process for the systematic review of the cases of female genital anomalies that could not fit into a specific class of the American Fertility Society (AFS) system.

Among the 143 remaining articles retrieved for detailed evaluation, 23 were excluded: 15 articles were excluded because the anomaly was described as ‘exceptional’ but could be easily classified with AFS classification system (i.e. unicornuate uterus with a non-communicating functional rudimentary horn) and 8 articles were excluded because the anomalies were not clearly described or they represented review articles or non-homogenous case series of anomalies already considered in our analysis (Fig. 1).

Classifiability of the included cases

The 120 papers included in the study reported on 140 cases, which could not properly fit into a specific class of the AFS system.

These 140 cases were clustered in 39 different types of anomalies (Table I); the uterus was the organ most frequently involved (30/39: 76.9%), followed by cervix (26/39: 66.7%) and vagina (23/39: 59%). The congenital anomaly involved a single organ in 12 types of anomalies (12/39: 30.8%), while multiple organs and/or segments of Müllerian ducts in more than one stages of embryologic development (complex anomalies) were simultaneously affected in 27 types of anomalies (27/39: 69.2%).

Table I.

Classification of the previously un-classified cases using the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESHRE/ESGE) Classification system of female genital anomalies: the terminology provided by the authors for the description of the anomaly is ‘translated’ to that of the new system before classification.

| Publication | Uterus |

Cervix |

Vagina |

ESHRE/ESGE Classification | ‘Associated anomalies’ and comments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors’ description | ESHRE/ESGE terminology | Authors description | ESHRE/ESGE terminology | Authors description | ESHRE/ESGE terminology | |||

| Rajamaheswari et al. (2009), Di Spiezio Sardo et al. (2007) and Demirci et al. (1995) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Longitudinal vaginal septum | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U0 C0 V1 | |

| Cetinkaya et al. (2011) and Levy et al. (1997) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Perforated transverse vaginal septum | Transverse vaginal septum | U0 C0 V3 | Non-obstructive transverse vaginal septum (partial failure of canalization/vertical fusion defect with incomplete unification of urogenital sinus and paramesonephric duct) |

| Sala Barangé et al. (1991) | Normal | Normal | Septate | Septate | Normal | Normal | U0 C1V0 | |

| Acién et al. (2009) (case 6) | Normal | Normal | Septate | Septate | Septate | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U0 C1 V1 | |

| Morales-Roselló and Peralta Llorens (2011) | Normal | Normal | Bicervical | Double normal | Normal | Normal | U0 C2 V0 | |

| Candiani et al. (1996)*, Dunn and Hantes (2004)*, Goldberg and Falcone (1996)* and Keltz et al. (1994)* | Normal | Normal | Double* | Double | Double or septate vagina | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U0 C2 V1 | *One cervix is blind (not communicating with uterine cavity) |

| Shirota et al. (2009) and Varras et al. (2007)*§ | Normal | Normal | Double* | Double normal | Double vagina§ | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U0 C2 V1 | *Double cervix communicating bilaterally with uterine cavity § The use of term ‘double vagina’ is not correct as in such case the vagina is single and divided by a septum |

| Deffarges et al. (2001), Fujimoto et al. (1997), Grimbizis et al. (2004) and Parsanezhad et al. (2013) | Normal | Normal | Isolated segmental cervical atresia | Cervical Aplasia | Normal | Normal | U0 C4 V0 | |

| Casey and Laufer (1997) | Normal | Normal | Cervical Agenesis | Cervical Aplasia | Transverse vaginal septum | Transverse vaginal septum | U0 C4 V3 | |

| Gurbuz et al. (2005) and Omurtag et al. (2009) | Normal | Normal | Cervical agenesis | Cervical Aplasia | Partial vaginal agenesis | Vaginal aplasia | U0 C4 V4 | |

| Suh and Kalan (2008) | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | U2b C0 V0 | Associated anomalies: unilateral fallopian tube hypoplasia and ipsilateral ovarian agenesis |

| Shah and Laufer (2011) and Shavell et al. (2009) | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Two cervices | Septate | Obstructed hemivagina | Longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum | U2b C1 V2 | The use of term ‘two cervices’ is not correct as in such case the cervix is single and divided by a septum |

| Fedele et al. (2012) | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Septate | Septate | Imperforate hymen | Imperforate hymen | U2b C1 V3 | |

| Acién et al. (2009) (case 5) and Lev-Toaff et al. (1992) | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Bicervical | Double normal | Normal | Normal | U2b C2 V0 | |

| Balasch et al. (1996), Brown and Badawy (2013), Caliskan et al. (2008), Celik and Mulayim (2012), Chang et al. (2004), Duffy et al. (2004), Fatum et al. (2003), Guo et al. (2011), Heinonen (2006), Hundley et al. (2001), Ignatov et al. (2008). La Fianza et al. (1997), McBean and Brumsted (1994), Nigam et al. (2010), Oakes et al. (2010), Patton et al. (2004), Pavone et al. (2006), Ribeiro et al. (2010), Saygili-Yilmaz et al. (2004) and Wai et al. (2001) | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Cervical duplication or Double normal | Double normal | Septate | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U2b C2 V1 | |

| Hur et al. (2007), Fedele et al. (2013) (10/87 cases) and Acién et al. (2004c)* | Septate | Complete septate uterus | Double cervices | Double normal | Unilaterally obstructed vaginal septum | Longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum | U2b C2 V2 | * In the case of Acién et al. (2004c) associated malformation: an ectopic ureter joined to ipsilateral hemi-cervix |

| Capito and Sarnacki (2009)*, Gupta et al. (2007)*, Hucke et al. (1992) (2/3 cases), Perino et al. (1995), Singhal et al. (2003)* and Spitzer et al. (2008)* | Asymmetric septate uterus (Robert's uterus) | Complete septate | Normal | Unilateral cervical aplasia | Normal | Normal | U2b C3 V0 | * The described ‘obstructing’ uterine septum is the result of unilateral cervical aplasia |

| Ziebarth et al. (2007) (case 2) | Bicornuate | Partial bicorporeal | Single | Normal | Obstructed hemivagina | Longitudinal obstructive vaginal septum | U3aC0V2 | |

| Fedele et al. (2013) (1/87 case) | Bicornuate | Partial Bicorporeal | Septate | Septate | Unilateral obstructed hemivagina | Longitudinal obstructive vaginal septum | U3aC1V2 | |

| Fedele et al. (2013) (9/87 cases) | Bicornuate | Partial Bicorporeal | Bicollis | Double normal | Obstructed hemivagina | Longitudinal obstructive vaginal septum | U3aC2V2 | |

| Acién et al. (2009) (case 1), Fedder (1990) and Reddy and Laufer (2009) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Single | Normal | Single | Normal | U3bC0V0 | Probably the use of term ‘didelphys’ is not correct since according to AFS Didelphys is always associated with double cervix |

| Adair et al. (2011) and Altchek et al. (2009) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Single | Normal | Unilateral distal vaginal agenesis | Vaginal aplasia | U3b C0 V4 | Probably the use of term ‘didelphys’ is not correct since according to AFS Didelphys is always associated with double cervix * In the case of Acién et al. (2010a,b) associated malformations: Gardner's duct cyst, ipsilateral renal agenesis, blind hemibladder and ectopic ureterocele |

| Acién et al. (2009) (case 2) and Acién et al. (2010a,b)* | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Septate | Septate | Normal | Normal | U3b C1 V0 | |

| Acién et al. (2009) (case 3 and 4) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Septate | Septate | Septate | Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum | U3b C1 V1 | |

| Al-Hakeem et al. (2002), Altintaş (1998), Arıkan et al. (2010)*, Asha and Manila (2008)*, Attar et al. (2013)*, Ballesio et al. (2003), Broseta et al. (1991), Burgis (2001), Candiani et al. (1997), Carlson and Garmel (1992), Chaim et al. (1991), Cicinelli et al. (1999), Dhar et al. (2011)*, Donnez et al. (2007), Fedele et al. (2013) (63/87), Erdoğan et al. (1992), Frei et al. (1999), Gholoum et al. (2006), Hinckley and Milki (2003), Hoeffel et al. (1997)*, Imai et al. (2004)*, Jindal et al. (2009), Kim et al. (2007), Kimble et al. (2009)*, Lin et al. (1991), Madureira et al. (2006), Mandava et al. (2012), Pieroni et al. (2001), Prada Arias et al. (2005), Sardanelli et al. (1995), Shibata et al. (1995), Skondras et al. (1991), Stassart et al. (1992), Takagi et al. (2010), Tanaka et al. (1998), Tridenti et al. (1988), Varras et al. (2008), Vercellini et al. (2007), Vergauwen et al. (1997), Youssef (2013)*, Ziebarth et al. (2007) (case 1)* and Zurawin et al. (2004) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Double | Double normal | Obstructed hemivagina | Longitudinal obstructive vaginal septum | U3b C2 V2 | * The blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis define the OHVIRA syndrome |

| Coskun et al. (2008) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Double | Double normal | Obstructed unilateral vagina by a transverse vaginal septum | Transverse vaginal septum | U3b C2 V3 | |

| Moawad et al. (2009) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Double normal | Double normal | Longitudinal Vaginal Septum Coincident with an Obstructive Transverse Vaginal Septum | Longitudinal non-obstructing and obstructive transverse vaginal septum | U3b C2 V1+3 | |

| Growdon and Laufer (2008) and Singhal et al. (2013) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Double | Double normal | Lower vaginal agenesis | Vaginal aplasia | U3b C2 V4 | |

| Fedele et al. (2013) (4/87 cases), Acién et al. (2004b) and Acién et al. (2008) | Didelphys | Complete Bicorporeal | Unilateral cervical atresia | Unilateral cervical aplasia | Normal | Normal | U3b C3 V0 | |

| Singh and Sunita (2008) and Bakri et al. (1992) | Double | Complete Bicorporeal | Cervical agenesis | Cervix aplasia | Vaginal agenesis | Vaginal aplasia | U3b C4 V4 | |

| Jain et al. (2013) | Bicornuate septate uterus | Bicorporeal septate uterus | Single | Normal | Transverse vaginal septum | Transverse vaginal septum | U3c C0 V3 | |

| El Saman et al. (2011) | Hybrid septate and bicornuate uterus | Bicorporeal septate uterus | Single | Normal | Normal | Normal | U3c C0 V0 | |

| Nezhat and Smith (1999) | Unicornuate uterus with two rudimentary horns | Hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavities | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | U4a C0 V0 | Incomplete canalization of one Mullerian duct initiated from two distinct sites resulting in two cavitated horns Failure of lateral fusion |

| Engmann et al. (2004)* | Unicornuate uterus with normal external morphology | Hemi-uterus without rudimentary cavity with normal external morphology | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | U4b C0 V0 | |

| Deligeoroglou et al. (2007), Mais et al. (1994) and Heinonen (1997) | Unicornuate uterus without contralateral horn | Hemi-uterus without rudimentary cavity | Normal | Normal | Imperforate hymen and transverse vaginal septum | Imperforate hymen and transverse vaginal septum | U4b C0 V3+3 | |

| Wright et al. (2011) | Two hemi-uteri with endometrial cavities (no connection with normal cervix) | Aplastic Uterus with Bilateral rudimentary cavities | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | U5a/C0/V0 | |

| Goluda et al. (2006) | Bicornuate rudimentary uterine horns | Aplastic uterus with rudimentary bilateral functional horns | Cervical agenesis | Cervix aplasia | Vaginal agenesis | Vaginal aplasia | U5a C4 V4 | |

| Christopoulos et al. (2009) | Didelphys uterus with noncanalized horns | Aplastic Uterus with Bilateral rudimentary horns without cavity | Double | Double normal | Normal | Normal | U5b C2 V0 | Probably the use of term ‘didelphys’ is not correct since according to AFS individual horns are not fully developed and have no cavity |

| Sadik et al. (2002) | ‘Middle’ hypoplastic non-cavitated uterus/Two rudimentary horns—no endometrium | Aplastic uterus* | Sole cervix, small in size with non-patent lumen | Cervical aplasia* | Normal | Normal | U5b/C4/V0 | *Cervical, uterine body and isthmus remnants. The described hypoplastic non-cavitated uterus is simply the hypoplastic isthmus without cavity attached to a ‘cervix’ without lumen |

| Medema et al. (2008) | Tricavitated | Normal uterus with two additional rudimentary functional horns | Not described clearly | Normal? | Normal? | Normal? | U6 C0 V0 | There are two possible explanation of this anomaly: Mullerian ‘duplication’ at the level of uterine body responsible for the presence of the two functional rudimentary horns Aplasia of the mid part of the uterus combined with a fusion defect of the upper part |

AFS, American Fertility Society; OHVIRA, Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly.

In all 39 types of anomalies, the ESHRE/ESGE classification system provided a comprehensive description of each single or complex anomaly (Table I). A precise categorization of single or complex anomalies was reached in 38 out of the 39 different types studied. In the following cases a consultation with the fourth reviewer was necessary before classification: Capito and Sarnacki (2009), Gupta et al. (2007) and Singhal et al. (2003) (Robert's uterus or Complete septate uterus/unilateral cervical aplasia/normal vagina ESHRE/ESGE Class U2b C3 V0), Nezhat and Smith (1999) (Hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavities/ESHRE/ESGE Class U4a C0 V0), Wright et al. (2011) (Aplastic uterus with bilateral rudimentary cavities ESHRE/ESGE Class U5a C0 V0), Sadik et al. (2002) (Aplastic uterus/cervical aplasia/normal vagina/ESHRE/ESGE Class U5b C4 V0), Medema et al. (2008) (Normal uterus with rudimentary horns/ESHRE/ESGE Class U6). The case reported by Nezhat and Smith (1999) having a hemi-uterus with ipsilateral rudimentary horns with cavity could be classified as Hemi-uterus with rudimentary cavity (ESHRE/ESGE Class U4a C0 V0) since the presence of the cavity and not the number is the clinically important parameter for the classification. The only anomaly that could not be perfectly categorized with the ESHRE/ESGE system was that reported by Medema et al. (2008), in which a ‘tricavitated’ uterus was described (Table I).

Discussion

Although several classification systems for female genital tract anomalies have been proposed (AFS, 1988; Acién et al., 2004a, 2011; Oppelt et al., 2005), the AFS classification is still the most widely used for categorizing such abnormalities. The AFS system provides a description and classification of the main uterine anomalies appropriate for the vast majority of the patients. However, it is not comprehensive, which hampers precise description of each anomaly and prediction of feasibility and safety of surgical correction (Mazouni et al., 2008; Saravelos et al., 2008; Grimbizis and Campo, 2010).

Thus, ‘obstructive’ anomalies, as a result of cervical and/or vaginal aplasias and/or dysplasias in the presence of either a normal or deformed but functional uterus, are not represented in the AFS classification system. Malformations with anatomical characteristics included in more than one category cannot be classified individually and precisely. AFS class I, including cases with hypoplasia and/or dysgenesis of the vagina, cervix, uterus and/or adnexae, incorporates severe and complex types of congenital anomalies with serious clinical manifestations usually needing complex surgical treatments. A clear and accurate classification is a prerequisite for their treatment, which is not the case with the AFS system. It is noteworthy to mention that these limitations also gave rise to further subdivisions for these categories of anomaly (Rock et al., 1995, 2010; Joki-Erkkilä and Heinonen, 2003; Troiano and McCarthy, 2004; Strawbrigde et al., 2007).

In 38 out of 39 types of anomalies included in this study as previously un-classified, the ESHRE/ESGE classification provided a comprehensive description and categorization of each single or complex anomaly in all cases.

All these 39 types of anomalies could not be described and categorized previously with the AFS system; as a consequence the terminology used by the authors to describe them is often ‘liberal’ and mostly subjective. The ESHRE/ESGE classification system gives the opportunity to replace inappropriate descriptions within the AFS system (i.e. ‘didelphys’ in presence of single cervix or ‘two cervices’ in presence of single cervix with a septum) or subjective and mostly ‘liberal’ terms due to the absence of terminology (i.e. ‘obstructive hemivagina’ or ‘hybrid septate and bicornuate uterus’) with the more objective ones used for the classes and sub-classes of the system such as ‘complete bicorporeal uterus with single cervix’, ‘septate cervix’, ‘longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum’ and ‘bicorporeal septate’, respectively. This is a ‘proof’ that with the use of the new ESHRE/ESGE system, a common terminology could be adopted for communication among clinicians to convey the exact anatomical status of the female genital tract, which is the primary basic characteristic in the design of the classes and sub-classes of the system.

The only anomaly that could not be perfectly categorized with the ESHRE/ESGE system was that of a reported ‘tricavitated’ uterus (Medema et al., 2008). According to the ESHRE/ESGE classification system this ‘bizarre’ uterine anomaly was clearly described as ‘normal uterus with two additional rudimentary functional horns’, but a precise categorization was not possible (i.e. U6C0V0). Two possible explanations of this complex uterine anomaly can be given: (i) Müllerian ‘duplication’ at the level of the uterine body responsible for the presence of the two functional rudimentary horns or (ii) aplasia of the mid part of the uterus combined with a fusion defect of the upper part. Indeed, potential duplication defects of Müllerian ducts like that of Medema et al. (2008), could not be categorized with the use of the new system by its design. In another case of ‘perforated’ vaginal septum, although it could be successfully classified with the ESHRE/ESGE system, the clinical importance of the existing perforation would have been underestimated without adding a proper comment.

An important characteristic of the ESHRE/ESGE classification system is the independent classification of uterine, cervical and vaginal anomalies. Thus, 22 out of the 39 types of anomalies (54.2%) were related to ‘obstructive’ anomalies that could not be described by the AFS classification system. All these cases could be easily and precisely classified into specific subclasses of the ESHRE/ESGE classification system due to this characteristic of the system. Furthermore, 7 out of the 39 (18%) types of anomalies identified referred to cases of hypoplasia and/or dysgenesis of the vagina, cervix and/or the uterus. All these malformations, otherwise nondescript or inappropriately grouped together into the same class I of the AFS classification system, could be properly and correctly classified into subclasses, expressing each one as a specific anatomical deviation. In other words, complex anomalies could be easily classified, due to the possibility to describe independently anomalies of different areas of the genital tract (uterus, cervix and vagina) and combine them case by case. However, it should be noted that, although some of these complex anomalies may be classified equally successfully by using other existing classifications (e.g. U2bC2 of the ESHRE/ESGE classification equates to C1U1c of the VCUAM classification), those systems have other disadvantages (Grimbizis and Campo, 2010), which would limit their use.

The new classification also ‘promotes’ the description of ‘associated anomalies of non-Müllerian origin’, which is so important particularly in the complex anomalies where a significant number will have associated renal tract malformations. This was not accounted for in the AFS classification and is a further advantage of the new classification.

Another important advantage of the ESHRE/ESGE classification system is that embryological origin has been adopted as the secondary basic characteristic in the design of the main classes. In fact, using this classification we could have an image of the embryological defect and, for example, such a rare anomaly as ‘Robert's uterus’ could be easily categorized as ‘complete septate uterus with unilateral cervical aplasia’ (U2bC3V0).

The system seems to be simple and functional because it has a direct and obvious association with the anatomy of the female genital system, without using complicated tables. As the AFS committee for the classification of congenital anomalies pointed out, the scheme of any classification system should be given in one page and this is fulfilled completely with the ESHRE/ESGE system. Furthermore, for cases where the anatomy is very difficult to be described only with the subclasses of the system (e.g. tricavitated uterus), an additional note could be made within the classification scheme (see ‘Comments’ in Table I). This may improve the skillful combination of simplicity and comprehensiveness.

From our analysis, uterine anomalies defined as ‘arcuate’ uterus with the AFS system are not included because this category no longer exists in the ESHRE/ESGE classification system and the patients should be categorized as normal or septate, depending on the degree of midline indentation; thus all these patients could be classified with the new system, albeit in a different way. Furthermore, accessory and cavitated uterine masses (ACUM) were excluded because their pathogenesis is still controversial. Although some authors consider them as a new type of Müllerian anomaly (probably related to a dysfunction of the female gubernaculum), others support the notion that they are simply adenomyotic cysts (Acién et al., 2010a, 2011, 2012; Bedaiwy et al., 2013).

Conclusions

An important characteristic of an ‘ideal’ classification system is to be comprehensive, incorporating all possible variations and offering a clear and distinct description and categorization for them. This facilitates enormously diagnosis and differential diagnosis, evaluation of their prognosis and planning their treatment. The new ESHRE/ESGE classification system may overcome the limits of the previous classification systems, providing an effective and comprehensive categorization of almost all the currently known anomalies of the female genital tract.

Suggestions for future research

The comprehensiveness of the ESHRE/ESGE classification adds objective scientific validity to its use. This may, therefore, promote its further dissemination and acceptance, which will have a positive outcome in clinical care and research. Offering a common language between the researchers, in the near future the ESHRE/ESGE classification system of female genital anomalies could be used as a tool for the development of guidelines for their diagnosis and treatment, further facilitating daily clinical practice.

Authors' roles

Conception and design: G.G., A.D.S.S., R.C. and S.G.; Literature search and data extraction: A.D.S.S., M.S and C.C.; Assessment of the quality of studies: A.D.S.S., M.S and C.C.; Analysis and interpretation of the data: A.D.S.S., M.S, C.C. and G.G.; Drafting the article: A.D.S.S. and G.G.; Critical revision of the article: all the authors (CONUTA Scientific Committee); Approval of results: CONUTA Scientific Committee.

Funding

The authors declare no source of funding or other financial support. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE).

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Acién P, Acién MI. The history of female genital tract malformation classifications and proposal of an updated system. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17:693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién M, Sanchez-Ferrer M. Complex malformations of the female genital tract. New Types and revision of classification. Hum Reprod 2004a;19:2377–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Sánchez-Ferrer M, Mayol-Belda MJ. Unilateral cervico-vaginal atresia with ipsilateral renal agenesis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004b;117:249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Susarte F, Romero J, Galán J, Mayol MJ, Quereda FJ, Sánchez-Ferrer M. Complex genital malformation: ectopic ureter ending in a supposed mesonephric duct in a woman with renal agenesis and ipsilateral blind hemivagina. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004c;117:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién M, Fernández S. Segmentary atresias in Müllerian malformations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;141:186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién M, Sánchez-Ferrer ML. Müllerian anomalies ‘without a classification’: from the didelphys-unicollis uterus to the bicervical uterus with or without septate vagina. Fertil Steril 2009;91:2369–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién M, Fernández F, José Mayol M, Aranda I. The cavitated accessory uterine mass: a Müllerian anomaly in women with an otherwise normal uterus. Obstet Gynecol 2010a;116:1101–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién M, Romero-Maroto J. Blind hemibladder, ectopic ureterocele, or Gartner's duct cyst in a woman with Müllerian malformation and supposed unilateral renal agenesis: a case report. Int Urogynecol J 2010b;21:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Sánchez del Campo F, Mayol MJ, Acién M. The female gubernaculum: role in the embryology and development of the genital tract and in the possible genesis of malformations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Bataller A, Fernandez F, Acin MI, Rodrguez JM, Mayol MJ. New cases of accessory and cavitated uterine masses (ACUM): a significant cause of severe dysmenorrhea and recurrent pelvic pain in young women. Hum Reprod 2012;27:683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair L, II, Georgiades M, Osborne R, Ng T. Uterus didelphys with unilateral distal vaginal agenesis and ipsilateral renal agenesis: common presentation of an unusual variation. J Radiol Case Rep 2011;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hakeem MM, Ghourab SA, Gohar MR, Khashoggi TY. Uterine didelphus with obstructed hemivagina. Saudi Med J 2002;23:1402–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altchek A, Brodman M, Schlosshauer P, Deligdisch L. Laparoscopic morcellation of didelphic uterus with cervical and renal aplasia. JSLS 2009;13:620–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altintaş A. Uterus didelphys with unilateral imperforate hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 1998;11:25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Fertility Society. The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril 1988;49:944–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arıkan Iİ, Harma M, Harma Mİ, Bayar U, Barut A. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome (uterus didelphys, blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis)—a case report. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2010;11:107–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha B, Manila K. An unusual presentation of uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis. Fertil Steril 2008;90:849.e9–849.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attar R, Yıldırım G, Inan Y, Küzılkale O, Karateke A. Uterus didelphys with an obstructed unilateral vagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: a rare cause of dysmenorrhoea. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2013;14:242–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakri YN, al-Sugair A, Hugosson C. Bicornuate nonfused rudimentary uterine horns with functioning endometria and complete cervical-vaginal agenesis: magnetic resonance diagnosis. Fertil Steril 1992;58:620–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasch J, Moreno E, Martinez-Román S, Moliní JL, Torné A, Sánchez-Martín F, Vanrell JA. Septate uterus with cervical duplication and longitudinal vaginal septum: a report of three new cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1996;65:241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesio L, Andreoli C, De Cicco ML, Angeli ML, Manganaro L. Hematocolpos in double vagina associated with uterus didelphus: US and MR findings. Eur J Radiol 2003;45:150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedaiwy MA, Henry DN, Elguero S, Pickett S, Greenfield M. Accessory and cavitated uterine mass with functional endometrium in an adolescent: diagnosis and laparoscopic excision technique. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26:89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broseta E, Boronat F, Ruiz JL, Alonso M, Osca JM, Jiménez-Cruz JF. Urological complications associated to uterus didelphys with unilateral hematocolpos. A case report and review of the literature. Eur Urol 1991;20:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SJ, Badawy SZ. A rare mullerian duct anomaly not included in the classification system by the American society for reproductive medicine. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2013;2013:569480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgis J. Obstructive Müllerian anomalies: case report, diagnosis, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan E, Cakiroglu Y, Turkoz E, Corakci A. Leiomyoma on the septum of a septate uterus with double cervix and vaginal septum: a challenge to manage. Fertil Steril 2008;89:456.e3–456.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiani M, Busacca M, Natale A, Sambruni I. Bicervical uterus and septate vagina: report of a previously undescribed Müllerian anomaly. Hum Reprod 1996;11:218–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiani GB, Fedele L, Candiani M. Double uterus, blind hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: 36 cases and long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capito C, Sarnacki S. Menstrual retention in a Robert's uterus. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22:e104–e106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RL, Garmel GM. Didelphic uterus and unilaterally imperforate double vagina as an unusual presentation of right lower-quadrant abdominal pain. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:1006–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey AC, Laufer MR. Cervical agenesis: septic death after surgery. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:706–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik NY, Mulayim B. A mullerian anomaly ‘without classification’: septate uterus with double cervix and longitudinal vaginal septum. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2012;51:649–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetinkaya SE, Kahraman K, Sonmezer M, Atabekoglu C. Hysteroscopic management of vaginal septum in a virginal patient with uterus didelphys and obstructed hemivagina. Fertil Steril 2011;96:e16–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaim W, Kornmehl P, Kopernik G, Meizner I. Uterus didelphys with unilateral imperforate vagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: the challenge of noninvasive diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound 1991;19:583–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AS, Siegel CL, Moley KH, Ratts VS, Odem RR. Septate uterus with cervical duplication and longitudinal vaginal septum: a report of five new cases. Fertil Steril 2004;81:1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos P, Deligeoroglou E, Liapis A, Agapitos E, Papadias K, Creatsas G. Noncanalized horns of uterus didelphys with prolapse: a unique case in a young woman. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2009;67:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicinelli E, Romano F, Didonna T, Schonauer LM, Galantino P, Di Naro E. Resectoscopic treatment of uterus didelphys with unilateral imperforate vagina complicated by hematocolpos and hematometra: case report. Fertil Steril 1999;72:553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A, Okur N, Ozdemir O, Kiran G, Arýkan DC. Uterus didelphys with an obstructed unilateral vagina by a transverse vaginal septum associated with ipsilateral renal agenesis, duplication of inferior vena cava, high-riding aortic bifurcation, and intestinal malrotation: a case report. Fertil Steril 2008;90:2006.e9–2006.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffarges JV, Haddad B, Musset R, Paniel BJ. Utero-vaginal anastomosis in women with uterine cervix atresia: long-term follow-up and reproductive performance. a study of 18 cases. Hum Reprod 2001;16:1722–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deligeoroglou E, Deliveliotou A, Makrakis E, Creatsas G. Concurrent imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and unicornuate uterus: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:1446–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci F, Kuyumcuoglu U, Api M, Uludogan M. Longitudinal vaginal septum: an unusual cause of postpartum total uterine prolapse. J Pak Med Assoc 1995;45:221–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar H, Razek YA, Hamdi I. Uterus didelphys with obstructed right hemivagina, ipsilateral renal agenesis and right pyocolpos: a case report. Oman Med J 2011;26:447–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Bettocchi S, Bramante S, Guida M, Bifulco G, Nappi C. Office vaginoscopic treatment of an isolated longitudinal vaginal septum: a case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007;14:512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J. Didelphic uterus and obstructed hemivagina: recurrent hematometra in spite of appropriate classic surgical treatment. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2007;63:98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DA, Nulsen J, Maier D, Schmidt D, Benadiva C. Septate uterus with cervical duplication: a full-term delivery after resection of a vaginal septum. Fertil Steril 2004;81:1125–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn R, Hantes J. Double cervix and vagina with a normal uterus and blind cervical pouch: a rare müllerian anomaly. Fertil Steril 2004;82:458–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Saman AM, Nasr A, Tawfik RM, Saadeldeen HS. Müllerian duct anomalies: successful endoscopic management of a hybrid bicornuate/septate variety. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2011;24:e89–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engmann L, Schmidt D, Nulsen J, Maier D, Benadiva C. An unusual anatomic variation of a unicornuate uterus with normal external uterine morphology. Fertil Steril 2004;82:950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan E, Okan G, Daragenli O. Uterus didelphys with unilateral obstructed hemivagina and renal agenesis on the same side. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1992;71:76–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatum M, Rojansky N, Shushan A. Septate uterus with cervical duplication: rethinking the development of müllerian anomalies. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003;55:186–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedder J. Uterus didelphys associated with duplex kidneys and ureters. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1990;69:665–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L, Frontino G, Motta F, Restelli E. A uterovaginal septum and imperforate hymen with a double pyocolpos. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1637–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L, Motta F, Frontino G, Restelli E, Bianchi S. Double uterus with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: pelvic anatomic variants in 87 cases. Hum Reprod 2013;28:1580–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei KA, Bonel HM, Häberlin FC. Uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis with excessive chronic vaginal discharge. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:460–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto VY, Miller JH, Klein NA, Soules MR. Congenital cervical atresia: report of seven cases and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:1419–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholoum S, Puligandla PS, Hui T, Su W, Quiros E, Laberge JM. Management and outcome of patients with combined vaginal septum, bifid uterus, and ipsilateral renal agenesis (Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome). J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:987–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JM, Falcone T. Double cervix and vagina with a normal uterus: an unusual Mullerian anomaly. Hum Reprod 1996;11:1350–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goluda M, St Gabryś M, Ujec M, Jedryka M, Goluda C. Bicornuate rudimentary uterine horns with functioning endometrium and complete cervical-vaginal agenesis coexisting with ovarian endometriosis: a case report. Fertil Steril 2006;86:462.e9–462.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Campo R. Congenital malformations of the female genital tract: the need for a new classification system. Fertil Steril 2010;94:401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Tsalikis T, Mikos T, Papadopoulos N, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN. Successful end-to-end cervico-cervical anastomosis in a patient with congenital cervical fragmentation: case report. Hum Reprod 2004;19:1204–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Brucker S, De Angelis C, Gergolet M, Li TC, Tanos V, Brölmann H, Gianaroli L, et al. The ESHRE-ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Gynecol Surg 2013a;10:199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Brucker S, De Angelis C, Gergolet M, Li TC, Tanos V, Brölmann H, Gianaroli L, et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod 2013b;28:2032–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growdon WB, Laufer MR. Uterine didelphys with duplicated upper vagina and bilateral lower vaginal agenesis: a novel Müllerian anomaly with options for surgical management. Fertil Steril 2008;89:693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo LQ, Cheng AL, Bhayana D. Case of the month #169: septate uterus with cervical duplication and vaginal septum. Can Assoc Radiol J 2011;62:226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Mittal S, Dadhwal V, Misra R. A unique congenital mullerian anomaly: Robert's uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;276:641–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbuz A, Karateke A, Haliloglu B. Abdominal surgical approach to a case of complete cervical and partial vaginal agenesis. Fertil Steril 2005;84:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen PK. Unicornuate uterus and rudimentary horn. Fertil Steril 1997;68:224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen PK. Complete septate uterus with longitudinal vaginal septum. Fertil Steril 2006;85:700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinckley MD, Milki AA. Management of uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. A case report. J Reprod Med 2003;48:649–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel C, Olivier M, Scheffler C, Chelle C, Hoeffel JC. Uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. Eur J Radiol 1997;25:246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucke J, DeBruyne F, Campo RL, Freikha AA. Hysteroscopic treatment of congenital uterine malformations causing hemi-hematometra: a report of three cases. Fertil Steril 1992;58:823–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundley AF, Fielding JR, Hoyte L. Double cervix and vagina with septate uterus: an uncommon müllerian malformation. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:982–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur JY, Shin JH, Lee JK, Oh MJ, Saw HS, Park YK, Lee KW. Septate uterus with double cervices, unilaterally obstructed vaginal septum, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: a rare combination of müllerian and wolffian anomalies complicated by severe endometriosis in an adolescent. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007;14:128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov A, Costa SD, Kleinstein J. Reproductive outcome of women with rare Müllerian anomaly: report of 2 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008;15:502–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai A, Takagi H, Matsunami K. Double uterus associated with renal aplasia; magnetic resonance appearance and three-dimensional computed tomographic urogram. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004;87:169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Gupta A, Kumar R, Minj A. Complete imperforate transverse vaginal septum with septate uterus: a rare anomaly. J Hum Reprod Sci 2013;6:74–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal G, Kachhawa S, Meena GL, Dhakar G. Uterus didelphys with unilateral obstructed hemivagina with hematometrocolpos and hematosalpinx with ipsilateral renal agenesis. J Hum Reprod Sci 2009;2:87–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joki-Erkkilä MM, Heinonen PK. Presenting and long-term clinical implications and fecundity in females with obstructing vaginal malformations. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2003;16:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltz MD, Berger SB, Comite F, Olive DL. Duplicate cervix and vagina associated with infertility, endometriosis, and chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:701–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TE, Lee GH, Choi YM, Jee BC, Ku SY, Suh CS, Kim SH, Kim JG, Moon SY. Hysteroscopic resection of the vaginal septum in uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 2007;22:766–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble RM, Khoo SK, Baartz D, Kimble RM. The obstructed hemivagina, ipsilateral renal anomaly, uterus didelphys triad. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Fianza A, Campani R, Villa A, Dore R, Di Maggio EM, Preda L, Bertolotti GC. Communicating bicornuate uterus with double cervix and septate vagina: an uncommon malformation diagnosed with MR imaging. Eur Radiol 1997;7:235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Toaff AS, Kim SS, Toaff ME. Communicating septate uterus with double cervix: a rare malformation. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79:828–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy G, Warren M, Maidman J. Transverse vaginal septum: case report and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1997;8:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, Chen AC, Chen TY. Double uterus with an obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc 1991;90:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira AJ, Mariz CM, Bernardes JC, Ramos IM. Case 94: Uterus didelphys with obstructing hemivaginal septum and ipsilateral renal agenesis. Radiology 2006;239:602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mais V, Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Piras B, Melis GB. Endosonographic diagnosis, pre-operative treatment and laparoscopic removal with endoscopic stapler of a rudimentary horn in a woman with unicornuate uterus. Hum Reprod 1994;9:1297–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandava A, Prabhakar RR, Smitha S. OHVIRA syndrome (obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly) with uterus didelphys, an unusual presentation. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012;25:e23–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazouni C, Girard G, Deter R, Haumonte JB, Blanc B, Bretelle F. Diagnosis of Mullerian anomalies in adults: evaluation of practice. Fertil Steril 2008;89:219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBean JH, Brumsted JR. Septate uterus with cervical duplication: a rare malformation. Fertil Steril 1994;62:415–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema TJ, Dekker JJ, Mijatovic V, van de Velde WJ, Schats R, Hompes PG. A complex malformation of the uterus: report of a tricavitated uterus. Fertil Steril 2008;90:2012.e7–2012.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moawad NS, Mahajan ST, Moawad SA, Greenfield M. Uterus didelphys and longitudinal vaginal septum coincident with an obstructive transverse vaginal septum. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22:e163–e165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Roselló J, Peralta Llorens N. Bicervical normal uterus with normal vagina and anteroposterior disposition of the double cervix. Case Rep Med 2011;2011:303828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezhat CR, Smith KS. Laparoscopic management of a unicornuate uterus with two cavitated, non-communicating rudimentary horns: case report. Hum Reprod 1999;14:1965–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam A, Puri M, Trivedi SS, Chattopadhyay B. Septate uterus with hypoplastic left adnexa with cervical duplication and longitudinal vaginal septum: rare Mullerian anomaly. J Hum Reprod Sci 2010;3:105–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes MB, Hussain HK, Smith YR, Quint EH. Concomitant resorptive defects of the reproductive tract: a uterocervicovaginal septum and imperforate hymen. Fertil Steril 2010;93:268.e3–268.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omurtag K, Session D, Brahma P, Matlack A, Roberts C. Horizontal uterine torsion in the setting of complete cervical and partial vaginal agenesis: a case report. Fertil Steril 2009;91:1957.e13–1957.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppelt P, Renner SP, Brucker S, Strissel PL, Strick R, Oppelt PG, Doerr HG, Schott GE, Hucke J, Wallwiener D, et al. The VCUAM (Vagina Cervix Uterus Adnex Associated Malformation) Classification: a new classification for genital malformations. Fertl Steril 2005;84:1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsanezhad ME, Namavar Jahromi B, Salarian L, Parsa-Nezhad M. Surgical management of a rare form of cervical dysgenesis with normal vagina, normal vaginal portion of the cervix and obstructed uterus. Arch Iran Med 2013;16:246–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton PE, Novy MJ, Lee DM, Hickok LR. The diagnosis and reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal septum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1669–1675; discussion 1675–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavone ME, King JA, Vlahos N. Septate uterus with cervical duplication and a longitudinal vaginal septum: a müllerian anomaly without a classification. Fertil Steril 2006;85:494.e9–494.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perino A, Chianchiano N, Simonaro C, Cittadini E. Endoscopic management of a case of ‘complete septate uterus with unilateral haematometra’. Hum Reprod 1995;10:2171–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni C, Rosenfeld DL, Mokrzycki ML. Uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. A case report. J Reprod Med 2001;46:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada Arias M, Muguerza Vellibre R, Montero Sánchez M, Vázquez Castelo JL, Arias González M, Rodríguez Costa A. Uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina and multicystic dysplastic kidney. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2005;15:441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamaheswari N, Seethalakshmi K, Gayathri KB. Case of longitudinal vaginal septum with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:1509–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy J, Laufer MR. Congenital anomalies of the female reproductive tract in a patient with Goltz syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009;22:e71–e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro SC, Yamakami LY, Tormena RA, Pinheiro Wda S, Almeida JA, Baracat EC. Septate uterus with cervical duplication and longitudinal vaginal septum. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2010;56:254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JA, Carpenter SE, Wheeless CR, Jones HWJ. The clinical management of maldevelopment of the uterine cervix. J Pelv Surg 1995;1:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rock JA, Roberts CP, Jones HW. Congenital anomalies of the uterine cervix: lessons from 30 cases managed clinically by a common protocol. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1858–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadik S, Taskin O, Sehirali S, Mendilcioglu I, Onoğlu AS, Kursun S, Wheeler JM. Complex Müllerian malformation: report of a case with a hypoplastic non-cavitated uterus and two rudimentary horns. Hum Reprod 2002;17:1343–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala Barangé X, Tomás Batlle X, Luburich Hernaiz P, Rodriguez Vernet A. Cervical uterus septus. Atypical malformation as a cause of sterility. J Radiol 1991;72:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li T-C. Prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure: a critical appraisal. Hum Reprod Update 2008;14:415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardanelli F, Renzetti P, Oddone M, Tomà P. Uterus didelphys with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: MR findings before and after vaginal septum resection. Eur J Radiol 1995;19:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saygili-Yilmaz ES, Erman-Akar M, Bayar D, Yuksel B, Yilmaz Z. Septate uterus with a double cervix and longitudinal vaginal septum. J Reprod Med 2004;49:833–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DK, Laufer MR. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome with a single uterus. Fertil Steril 2011;96:e39–e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavell VI, Montgomery SE, Johnson SC, Diamond MP, Berman JM. Complete septate uterus, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal anomaly: pregnancy course complicated by a rare urogenital anomaly. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Nonomura K, Kakizaki H, Murayama M, Seki T, Koyanagi T. A case of unique communication between blind-ending ectopic ureter and ipsilateral hemi-hematocolpometra in uterus didelphys. J Urol 1995;153:1208–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirota K, Fukuoka M, Tsujioka H, Inoue Y, Kawarabayashi T. A normal uterus communicating with a double cervix and the vagina: a müllerian anomaly without any present classification. Fertil Steril 2009;91:935.e1–935.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Sunita V. Double uteri with cervicovaginal agenesis. Fertil Steril 2008;90:2016.e13–2016.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S, Agarwal U, Sharma D, Sirohiwal D. Pregnancy in asymmetric blind hemicavity of Robert's uterus—a previously unreported phenomenon. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;107:93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal SR, Lakra P, Bishnoi P, Rohilla S, Dahiya P, Nanda S. Uterus didelphys with partial vaginal septum and distal vaginal agenesis: an unusual anomaly. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2013;23:149–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skondras KG, Moutsouris CC, Vaos GC, Barouchas GC, Demetriou LD. Uterus didelphys with an obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: a rare cause of acute abdomen in pubertal girls. J Pediatr Surg 1991;26:1200–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RF, Caccia N, Kives S, Allen LM. Hysteroscopic unification of a complete obstructing uterine septum: case report and review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2008;90:2016.e17–2016.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stassart JP, Nagel TC, Prem KA, Phipps WR. Uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: the University of Minnesota experience. Fertil Steril 1992;57:756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbrigde LC, Crough NS, Cutner AS, Creighton SM. Obstructive Mullerian anomalies and modern laparoscopic management. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2007;20:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BY, Kalan MJ. Septate uterus with left fallopian tube hypoplasia and ipsilateral ovarian agenesis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2008;25:567–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Matsunami K, Imai A. Uterovaginal duplication with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: review of unusual presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;30:350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka YO, Kurosaki Y, Kobayashi T, Eguchi N, Mori K, Satoh Y, Nishida M, Kubo T, Itai Y. Uterus didelphys associated with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis: MR findings in seven cases. Abdom Imaging 1998;23:437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tridenti G, Armanetti M, Flisi M, Benassi L. Uterus didelphys with an obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis in teenagers: report of three cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;159:882–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RN, McCarthy SM. Müllerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical issues. Radiology 2004;233:19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varras M, Akrivis C, Demou A, Kitsiou E, Antoniou N. Double vagina and cervix communicating bilaterally with a single uterine cavity: report of a case with an unusual congenital uterine malformation. J Reprod Med 2007;52:238–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varras M, Akrivis Ch, Karadaglis S, Tsoukalos G, Plis Ch, Ladopoulos I. Uterus didelphys with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis complicated by pyocolpos and presenting as acute abdomen 11 years after menarche: presentation of a rare case with review of the literature. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2008;35:156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellini P, Daguati R, Somigliana E, Viganò P, Lanzani A, Fedele L. Asymmetric lateral distribution of obstructed hemivagina and renal agenesis in women with uterus didelphys: institutional case series and a systematic literature review. Fertil Steril 2007;87:719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergauwen S, De Schepper AM, Delbeke L. Unilateral intermittent occlusion of a bicornuate uterus in association with ipsilateral renal agenesis and vena cava inferior duplication. Rofo 1997;166:457–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wai CY, Zekam N, Sanz LE. Septate uterus with double cervix and longitudinal vaginal septum. A case report. J Reprod Med 2001;46:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KN, Okpala O, Laufer MR. Obstructed uteri with a cervix and vagina. Fertil Steril 2011;95:290.e17–290.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef MAFM. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly syndrome with uterus didelphys (OHVIRA). Middle East Fertil Soc J 2013;18:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebarth A, Eyster K, Hansen K. Delayed diagnosis of partially obstructed longitudinal vaginal septa. Fertil Steril 2007;87:697.e17–697.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurawin RK, Dietrich JE, Heard MJ, Edwards CL. Didelphic uterus and obstructed hemivagina with renal agenesis: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2004;17:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]