Abstract

Nearly 70% of HIV-infected individuals suffer from HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). HIV-1 transactivator of transcription (Tat) protein is known to synergize with abused drugs and exacerbate the progression of central nervous system (CNS) pathology. Cumulative evidences suggest that the HIV-1 Tat protein exerts the neurotoxicity through interaction with human dopamine transporter (hDAT) in the CNS. Through computational modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we develop a three-dimensional (3D) structural model for HIV-1 Tat binding with hDAT. The model provides novel mechanistic insights concerning how HIV-1 Tat interacts with hDAT and inhibits dopamine uptake in hDAT. In particular, according to the computational modeling, Tat binds most favorably with the outward-open state of hDAT. Residues Y88, K92, and Y470 of hDAT are predicted to be key residues involved in the interaction between hDAT and Tat. The roles of these hDAT residues in the interaction with Tat are validated by experimental tests through site-directed mutagensis and DA uptake assays. The agreement between the computational and experimental data suggests that the computationally predicted hDAT-Tat binding mode and mechanistic insights are reasonable and provide a new starting point to design further pharmacological studies on the molecular mechanism of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a lentivirus causing the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) disease.1, 2 According to the 2013 report of World Health Organization (WHO), a total number of 35.3 million people in the world are living with HIV/AIDS.3 Among the genes of HIV virus, the transactivator of transcription (Tat) gene plays a role in the regulation of proteins that control how the HIV virus infects cells.4-7 The HIV-1 positive cocaine abusers exhibit more serious neurological impairments, and also have higher rates of motor and cognitive dysfunction compared with HIV-1 negative drug abusers.8-11

The Tat protein has been detected in the brain and the sera of HIV-1 patients.12-14 Accumulating evidence1, 15-21 has revealed that HIV-1 Tat plays an important role in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) by disrupting intracellular communication.22 Specifically, HIV-1 Tat exerts its neurotoxicity through interaction with some crucial proteins in the central nervous system (CNS), such as monoamine (dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin) transporters and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors that are targets of some widely abused drugs including cocaine and methamphetamine. There have been extensive studies on these interactions and related problems.8, 18, 19, 21, 23-41 We are particularly interested in human dopamine transporter (hDAT) due to our long-standing research interest in development of cocaine abuse-related medications42-50 and the fact that hDAT is the primary target of cocaine in the CNS.51, 52 It has been reported that Tat and cocaine could synergistically impair hDAT function as demonstrated both in vivo53 and in vitro.1 Activity of presynaptic hDAT is strikingly reduced in HIV-1 patients with cocaine abuse.29, 54 As hDAT availability is correlated with HIV-1 associated neurocognitive deficits,55, 56 it has been estimated that ~70% of HIV-1 patients are suffering from HAND.6, 17, 20, 57 The prevalence of HAND and the complicated connection of the HIV-1 infection with cocaine abuse have made a high priority in understanding molecular mechanism of HIV-1 Tat associated neurotoxicity. Understanding the detailed molecular mechanism concerning how the HIV-1 Tat interacts with hDAT could provide valuable clues to rationally design novel and effective therapeutics for treatment of HAND.

It has been known19, 21, 58 that HAND-related abnormal neurocognitive function is associated with dysfunctions in dopamine (DA) neurotransmission. Protein hDAT picks up DA released from synaptic cleft and transports DA into pre-synaptic neurons.59-61 The transporting process must be assisted by the binding of two Na+ ions and one Cl− ion, and it has been known that this process involves three typical conformational states of hDAT: outward-open state (i.e. the extracellular side of substrate-binding site for the transmitter is open, while the intracellular side is blocked); the outward-occluded state (i.e. both the extracellular and intracellular sides of binding site are blocked such that the binding site is occluded and no longer accessible for substrate); and the inward-open state (i.e. the intracellular side of substrate-binding site is open, while the extracellular side is blocked).62-70

The present study aims to understand how hDAT interacts with HIV-1 Tat at molecular level, particularly the detailed hDAT-Tat binding mode. It is a grand challenge to determine an X-ray crystal structure of hDAT-Tat binding complex in the physiological membrane environment. There is also no X-ray crystal structure available for hDAT itself. On the other hand, state-of-the-art molecular modeling techniques provide a useful tool to model the possible hDAT-Tat binding. Previous computational studies63, 71-74 provided homology models of hDAT concerning the general features of conformational changes during dopamine transporting process by hDAT. The obtained hDAT models allow to investigate how hDAT interacts with dopamine, cocaine, and other interesting ligands.38,39 However, all of the previous studies, including those by our own group38,40,75 were based on the hDAT models built through homology modeling using the previously available X-ray crystal structure of the bacterial homolog Leucine transporter (LeuTAa)69 as a template, and the template LeuTAa shares less than 25% sequence identity with hDAT. It is generally recognized that structural models derived from homology modelling will be reliable only when the template has a higher sequence identity and higher evolutionary homology with the modeled protein.

It is very interesting to note that an X-ray crystal structure has recently been determined for drosophila dopamine transporter (dDAT)70. The sequences of dDAT and hDAT are very similar, with a sequence similarity reaching 59% (identity: 46%) which is considered rather high for homology modeling; in general, 40% sequence identity between a template protein and a target protein is considered sufficient for constructing a satisfactory homology model.76, 77 So, the newly available X-ray crystal structure of dDAT has become the most reasonable template for modeling the hDAT structures to be used in our studies on the hDAT structures and its binding with ligands. The newly built hDAT structures are consistent with all of the known structural insights obtained from previously reported wet-experimental validations on hDAT.63, 65, 66, 69, 70 The more reasonable models of hDAT have allowed us to study how hDAT interacts with HIV-1 Tat. This is the first report on the use of the new hDAT models (based on the X-ray crystal structure of dDAT) to study the possible hDAT-Tat binding mode. The hDAT-Tat binding structure is determined through protein-protein docking78 and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.79 Based on the determined hDAT-Tat binding structure, the HIV-1 Tat protein preferably binds with the outward-open state of hDAT, and critical residues contributing to the hDAT-Tat binding are identified. The computationally determined hDAT-Tat binding mode has been validated by experimental tests including site-directed mutagenesis and DA uptake assays. The new insights obtained from the current study provide a structural basis for future extensive studies on the molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 Tat associated neurotoxicity and the relationship between HIV-1 infection and drug abuse.

Results and Discussion

Binding mode of HIV-1 Tat with hDAT

To determine the hDAT-Tat binding structure, we first need to know the detailed structures of both hDAT and HIV-1 Tat. The hDAT structures were built from the X-ray crystal structure of dDAT (PDB code: 4M48)70 through homology modeling. The obtained structural model of hDAT are consistent with all of the known structural insights obtained from previously reported wet-experimental validations on hDAT.63, 65, 66, 69, 70 In particular, the hDAT model has all of the previously known general features of hDAT including D476-R85 salt bridge, orientation of F320 residue, binding sites of dopamine, Zn2+, Na+, and Cl−. Concerning HIV-1 Tat structure, B-type HIV-1 Tat (Tat Bru) is prevalent in the North America, and has 86 amino acids with a net charge of +12e at the physiological pH 7.4.80 Multinuclear NMR spectroscopy revealed that the Tat Bru protein exists in a random coil conformation, and only transient folding can occur in its Cys-rich region (residues #22 to #37, see Figure S1 in Supporting Information) and its core region (residues #38 to #48). All of the 11 conformations of HIV-1 Tat obtained from NMR studies (PDB entry as 1JFW)80 are quite similar, with the average positional root-mean square deviation (RMSD) of the backbone atoms being 1.3 Å. Starting from the NMR structures of HIV-1 Tat,80 it is also important to know which one of the three conformational states of hDAT, i.e. the outward-open state, outward-occluded state, and inward-open state, are more favored for the binding with HIV-1 Tat protein. For this purpose, a protein-protein docking program, ZDOCK 3.0.2,78 was used to explore possible hDAT-Tat complex structures (see Supporting Information for the computational details). As shown in Figure 1A, the calculated electrostatic potentials and the molecular dipole moments of both HIV-1 Tat and hDAT indicate that the long-range electrostatic attraction may act as a driving force for the association of these two proteins. Such obvious charge anisotropy between these two proteins drives HIV-1 Tat approaching to the mouth of the vestibule near the extracellular region of hDAT. This suggests that the HIV-1 Tat interacts directly with hDAT residues around the extracellular region of hDAT. Therefore, our protein-protein docking was focused on docking the HIV-1 Tat protein into the extracellular region for each of the three conformational states of hDAT, and a total of 3,000 candidates (including all of the three possible conformational states of hDAT with various poses and conformations of HIV-1 Tat) were selected from all the docking results as initial complex structures. Further, as the rigid-body protein-protein docking cannot account for the conformational flexibility of the proteins, the initial complex structures obtained from the protein-protein docking were refined through a series of energy-minimizations, MD simulations, and molecular mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA)81 binding energy calculations (see Supporting Information for the computational details) to capture the most favorable hDAT-Tat binding structure. Through the modeling and MD simulations, we were able to identify the best possible hDAT-Tat binding mode for each conformational state (outward-open, outward-occluded, or inward-open) of hDAT. According to the obtained binding structures and energies, HIV-1 Tat can bind with only the outward-open structure of hDAT due to the excellent geometrical match and favorable binding energy, and the outward-occluded and inward-open states cannot bind with HIV-1 Tat due to the bad geometrical match and unfavorable binding energies. Hence, our discussion below will focus on HIV-1 Tat binding with the outward-open state of hDAT.

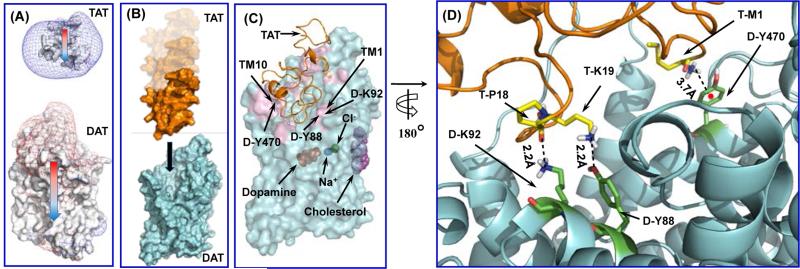

Figure 1.

The simulated process of binding between HIV-1 Tat and hDAT in the outward-open state. (A) The HIV-1 Tat approaches hDAT through long-range electrostatic attractions, as indicated by the electrostatic potential contour maps for these two proteins. Isopotential surfaces are calculated at +4kBT/e for positively charged surface (shown as blue mesh) and at −3kBT/e for negatively charged surface (shown as red mesh) respectively. Colored arrows indicate the directions of the dipoles of both molecules. (B) The general process of two proteins approaching toward each other and form the initial encounter complex. Both proteins are represented as the surface style, with HIV-1 Tat in gold and hDAT in cyan. The black arrow indicates the HIV-1 Tat aligning to the vestibule near the extracellular side of hDAT. (C) Typical hDAT-Tat binding structure derived from the last snapshot of the MD trajectory #1 followed by the energy minimization. Tat is represented as gold ribbons. hDAT is represented by semi-transparent cyan surface. Substrate dopamine, cholesterol, sodium ions, chloride ion, and zinc ion are represented by the sphere style and colored in red, purple, blue, green, and yellow, respectively. The contact interface of hDAT between Tat and hDAT is colored in pink. It was observed that both TM10 and TM1 are involved in the interaction between Tat and hDAT. (D) Atomic interactions on the binding interface of the typical hDAT-Tat binding structure (as shown in C). HIV-1 Tat protein is shown as ribbon and colored in gold, and hDAT is shown as cyan ribbon. Residues T-M1, T-P18, and T-K19 of HIV-1 Tat are shown in ball-stick style and colored in yellow. Residues D-Y470, D-Y88, and D-K92 are shown in ball-stick style and colored in green. Dashed lines represent intermolecular hydrogen bonds with labeled distances. For D-Y470, the red point indicates the center of its aromatic ring, and the dashed line pointing to the red ball represents the cation-π interaction with labeled distance.

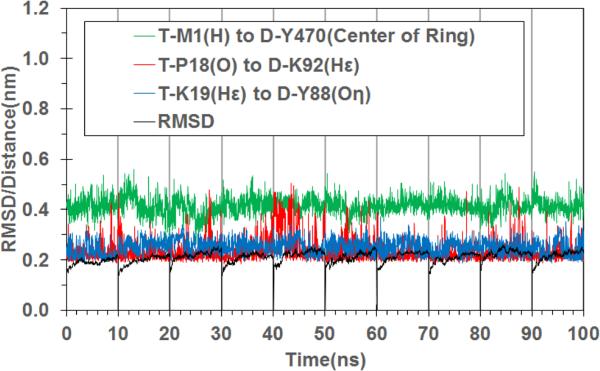

For the most favorable hDAT-Tat binding mode (with hDAT in the outward-open state), we further carried out the final MD simulations for a total of 100 ns, including 10 independent MD trajectories with 10 ns for each. It turned out that the 10 trajectories (MD trajectories #1 to #10) led to very similar binding structures, which gives us further confidence in the MD-simulated hDAT-Tat binding mode. For convenience, the specific hDAT-Tat binding structure discussed below will always refer to the MD trajectory #1, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Figure 1B depicts the general process of the hDAT-Tat binding, i.e. the HIV-1 Tat molecule diffuse around the extracellular side of hDAT (colored in cyan), and form an initial encounter complex with hDAT due to the electrostatic attraction, according to the computational modeling. Conformational adjustments around the binding interface lead to the formation of the final hDAT-Tat binding structure. Figure 1C represents a typical complex structure of HIV-1 Tat binding with the outward-open state of hDAT, which is derived from the last snapshot of the 10-ns MD trajectory. The HIV-1 Tat molecule sits just above the vestibule near the extracellular side of hDAT, and forms contacting interface which involves residues D-Y88, D-K92, and D-Y470. Such orientation of HIV-1 Tat will certainly block the entry pathway of substrate DA and, therefore, inhibit the transporting of DA by hDAT. Figure 1D depicts the critical intermolecular interactions as observed from this hDAT-Tat binding structure (Figure 1C). Specifically, these critical interactions include: the cation-π interaction between the positively charged amino-group of T-M1 at the N-terminus of HIV-1 Tat and the aromatic D-470 side chain of hDAT; the hydrogen bonding interaction between the positively charged head group of T-K19 side chain and the hydroxyl group of D-Y88 side chain; and the hydrogen bonding interaction between the backbone oxygen atom of T-P18 and the positively charged head group of D-K92 side chain. Depicted in Figure 2 are the tracked time-dependent distances of these critical intermolecular interactions and the positional RMSD for all backbone atoms of the MD-simulated hDAT-Tat complex in 10 MD trajectories for a total of 100 ns. As shown in Figure 2, the RMSD values for all of the 10 MD trajectories are around 2.11 ± 0.24 Å with small fluctuations, suggesting a high conformational stability of the hDAT-Tat binding structure. As shown in Figure 2, the cation-π interaction between T-M1 and D-Y470 had an average distance of 4.13 ± 0.35 Å (green curve), a weak hydrogen bond between T-K19 and D-Y88 had an average H...O distance of 2.52 ± 0.31 Å (blue curve), and another weak hydrogen bond between T-P18 and D-K92 had an average O...H distance of 2.33 ± 0.46 Å (red curve). These tracked distances suggest that all these hDAT-Tat interactions are persistent throughout the MD simulations.

Figure 2.

Tracked changes of critical distances and positional RMSD values for the hDAT-Tat binding structure based on the 10 MD trajectories (10 ns for each MD trajectory). Green curve refers to the distance between the positively charged amino group of T-M1 of HIV-1 Tat and the center of the aromatic ring at D-Y470 side chain. Blue curve represents the distance between the hydrogen atom on the positively charged head of T-K19 side chain and the hydroxyl oxygen atom of D-Y88 side chain, and the red curve refers to the distance between the backbone oxygen atom of T-P18 and the hydrogen atom on the positively charged head of D-K92 side chain. The black curve refers to the positional RMSD for the backbone atoms of the hDAT-Tat binding complex.

Validation of the predicted hDAT-Tat binding mode

For validation of the computationally predicted hDAT-Tat binding structure, we also carried out wet experimental studies including site-directed mutagenesis and DA-uptake assay (see the Methods section below; more extensive experimental assays and data will be reported elsewhere82) to determine the inhibitory effects of Tat on several hDAT mutants (including the Y470F, Y470H, Y470A, Y88F, and K92M mutants) in comparison with wild-type hDAT (WT-hDAT).

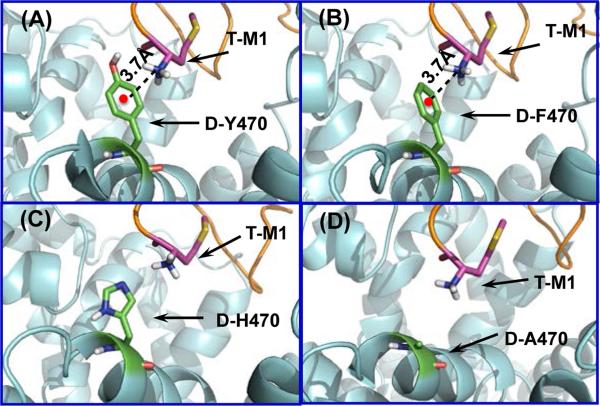

According to the hDAT-Tat binding structure (Figures 1 and 2), there is a strong cation-π interaction between the positively charged amino group of T-M1 (i.e. M1 of HIV-1 Tat) and the aromatic ring of D-Y470 (i.e. Y470 of hDAT) side chain. Therefore, mutation of D-Y470 to phenylalanine should not weaken the favorable cation-π interaction, but mutation of D-Y470 to any other amino acid without the aromatic ring would significantly decrease the hDAT-Tat binding and the inhibitory effect of Tat on hDAT, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Interactions between the positively charged amino group of T-M1 and the side chain of residue #470 of hDAT in the modeled complexes of HIV-1 Tat binding with WT-hDAT and its mutants. Structures of the Y470F, Y470H, and Y470A mutants of hDAT were modeled starting from that of WT-hDAT in the hDAT-Tat binding structure shown in Figure 1C and 1D by changing the Y470 side chain into the corresponding one of the mutant and then performing the energy minimization. (A) Residues T-M1 and D-Y470 are represented as sticks and colored by atom types. The red point represents the center of aromatic ring of residue #470 of hDAT, and the dashed line pointing to the red point represents the cation-π interaction with the distance labeled. (B) Y470F mutation retains the cation-π interaction between T-M1 and D-F470. The distance between the center of aromatic side chain of D-F470 and the nitrogen atom of the positively charged amino group of T-M1 is indicated in Å. (C) Residue D-H470 stays far away from the positively charged amino group of T-M1, i.e. no direct cation-π interaction. (D) Residue D-A470 stays further away from the positively charged amino group of T-M1, i.e. no direct cation-π interaction.

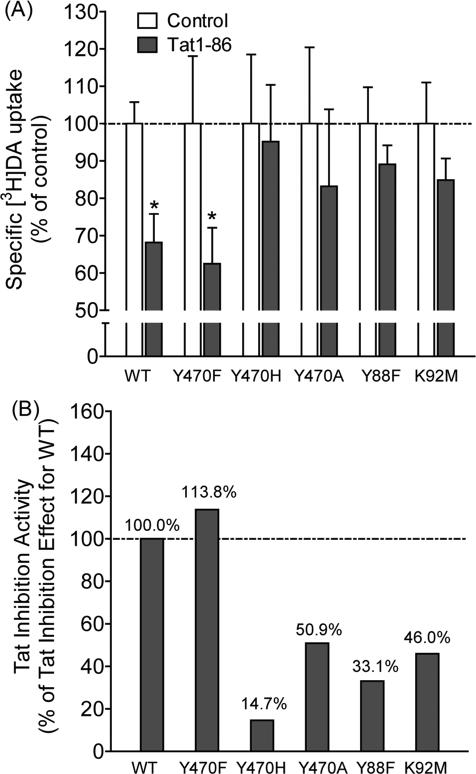

All of these computational insights are supported by the experimental data depicted in Figure 4. Experimental data (Figure 4A) revealed that, compared to their respective controls, exposure to Tat1-86 significantly decreased [3H]DA uptake in WT-hDAT by 33.0% and Y470F-hDAT by 37.6%, respectively; however, nearly negligible effects of Tat were observed in Y470H-hDAT, Y470A-hDAT, Y88F-hDAT, and K92M-hDAT. In addition, the Tat-mediated inhibitory effects on DA uptake were also expressed as a percent change from the DA uptake in WT-hDAT (100%) in the presence of Tat. As illustrated in Figure 4B, the Tat-induced inhibitory effect on DA uptake was dramatically reduced in Y470H-hDAT, Y470A-hDAT, Y88F-hDAT, and K92M-hDAT, suggesting that these mutants significantly attenuate Tat-induced inhibition of DA uptake.

Figure 4.

Effects of Tat on the kinetic analysis of [3H]DA uptake by WT-hDAT and its mutants. (A) PC12 cells transfected with WT-hDAT (WT) Y470F-hDAT (Y470F), Y470H-hDAT (Y470H), Y470A-hDAT (Y470A), Y88F-hDAT (Y88F) or K92M-hDAT (K92M) were preincubated with or without recombinant Tat1-86 (500 nM, final concentration) at room temperature for 20 min followed by the addition of 0.05 μM final concentration of the [3H]DA. *p < 0.05 compared to respective control in the absence of Tat (n=4). (B) The corresponding Tat-induced inhibitory effects on [3H]DA uptake in hDAT mutants were presented as the percentage of the Tat-induced inhibitory effect of [3H]DA uptake in WT-hDAT (100%) at the same concentrations of [3H]DA (0.05 μM) and Tat1-86 (500 nM).

As seen in Figure 4B, the Y470H and Y470A mutations on hDAT did decrease the inhibitory effect of Tat by ~85% and ~49%, respectively, and the Y470F mutation did not decrease the inhibitory effect of Tat at all. These experimental activity data strongly support the computationally predicted important role of the aromatic ring of D-Y470 side chain (see Figure 3A). The Y470F mutant of hDAT still has the aromatic side chain (see Figure 3B), which explains why the Y470F mutation did not decrease the inhibitory effect of Tat at all. In fact, the Y470F mutation slightly increased the inhibitory effect (bŷ14%). The Y470F mutation-induced slight increas in the inhibitory effect of Tat suggests that the cation-π interaction between the positively charged amino group of T-M1 and the aromatic ring (of D-Y470 side chain) becomes slightly stronger after the hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring is removed.

The Y470A mutation on hDAT changes the aromatic side chain of D-Y470 to a much smaller one (methyl group) and, thus, removes the favorable cation-π interaction (see Figure 3D), which explains why the Y470A mutation significantly decreased the inhibitory effect of Tat (by ~49%). The Y470H mutation not only removes the favorable cation-π interaction, but also produces unfavorable contacts with the positively charged amino group of T-M1 and, thus, the H470 side chain was pushed away from the positively charged amino group of T-M1 during the modeling process (see Figure 3C), which explains why the Y470H mutation even more significantly decreased the inhibitory effect of Tat (by ~85%) compared to the Y470A mutation (~49%).

In addition, Y88 and K92 of hDAT (i.e. D-Y88 and D-K92) are also predicted to be critical residues interacting with Tat through forming hydrogen bonds with K19 and P18 of Tat (i.e. T-K19 and T-P18), respectively (see Figures 1D and 2). So, the Y88F or K92M mutation on hDAT would decrease the hDAT-Tat binding and the inhibitory effect of Tat on hDAT. The experimental data in Figure 4B show that the Y88F and K92M mutations on hDAT indeed significantly decreased the inhibitory effect of Tat by ~67% and ~54%, respectively, supporting the favorable roles of the D-Y88 and D-K92 side chains. The agreement between the computational and experimental data suggests that the computationally determined hDAT-Tat binding mode is reasonable.

Finally, we would like to point out that understanding the molecular mechanism for hDAT-Tat interaction is the first step of the more extensive efforts that aim to understand how Tat interacts with other transporters and receptors in the CNS. The similar integrated computational strategy used in this report may be used to explore the structural models concerning how Tat interacts with other transporters and receptors. Understanding the detailed molecular mechanisms for Tat interacting with all of the relevant transporters and receptors, one could eventually have a chance to explore possible therapeutic agents that can block Tat binding with multiple transporters/receptors to combat HAND.

Conclusion

We have developed a reasonable 3D structural model of hDAT binding with HIV-1 Tat through protein-protein docking and molecular dynamics simulations. According to the computational data, HIV-1 Tat binds most favorably with the outward-open state of hDAT. Based on the modeled hDAT-Tat binding struture, residues Y88, K92, and Y470 of hDAT are predicted to be key residues for hDAT interacting with Tat. The computational predictions are supported by experimental tests including site-directed mutagenesis and dopamine uptake assays in the presence and absence of Tat. The good agreement between the computational and experimental data suggests that the computationally predicted hDAT-Tat binding mode is reasonable. The newly obtained hDAT-Tat binding mode provides novel mechanistic insights concerning how HIV-1 Tat interacts with hDAT and inhibits the dopamine transporting in hDAT. Starting from the new hDAT-Tat binding mode and mechanistic insights, one may design further studies to explore the more detailed molecular mechanisms and develop potentially effective therapeutics for treatment of HIV-1 associated neurocognitive disorders. In general, this study also demonstrates how the complex structural and mechanistic questions concerning protein-protein interactions can be addressed by using a generally applicable strategy including integrated computational-experimental studies.

Methods

Molecular modeling

In order to dock HIV-1 Tat protein into the possible binding site on the extracellular side of hDAT, and to build the initial hDAT-Tat binding structure, protein-protein docking was performed by using the ZDOCK 3.0.2 program.78 The 11 conformations of HIV-1 Tat based on NMR structural analysis 80 were all treated equally as the ligand protein, and structures of the three conformational states of hDAT (generated by the Modeller module of Discovery 2.583 and –energy-optimized using the AMBER 12 software package79) were treated as the receptor protein. For each of the three conformational states of hDAT (i.e. the outward-open, outward-occluded, and inward-open states), 10 snapshots were selected with a 1-ns interval from a 10-ns trajectory of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the production stage. In order to probe whether there is a charge anisotropy between these two proteins, the electrostatic potentials and the molecular dipole moments for both HIV-1 Tat and hDAT were calculated by using the PDB2PQR server.84 Since the HIV-1 Tat bears positive electrostatic potential on its surface, and the hDAT bears negative electrostatic potential on the surface of its extracellular side, these two proteins are expected to electrostatically attract each other along the direction of their dipole moments. Based on this piece of information, it is reasonable to assume that the HIV-1 Tat would probably bind with hDAT at a site around the extracellular region of hDAT. During the protein-protein docking process, the rotational sampling (with 6° angular sampling) method implemented in the ZDOCK 3.0.2 was used in order to make a more complete configuration sampling for these two proteins. The score function of ZRANK85 program was used to score the binding energy between the ligand protein (HIV-1 Tat) and the receptor protein (hDAT). For each protein-protein docking, the program was set to output top-2,000 candidates as the possible binding complexes. The docking of 11 HIV-1 Tat conformations into the hDAT structures associated with the 10 MD snapshots (i.e. 10 conformations) for each conformational state of hDAT (e.g. the outward-open state) generated 11 × 10 × 2000 = 220,000 candidates of the binding structure. Considering that the HIV-1 Tat should contact directly with residues around the mouth of the vestibule near the extracellular end of hDAT structure (as this vestibule and the substrate-entry pathway were explored in our previous studies on the homology modeling of hDAT and its inhibition by (−)-cocaine71, 73), we ruled out all candidate complexes that do not directly align with the residues around the mouth of the vestibule of hDAT. This initial screening reduced the 220,000 candidates to 1,000 candidates of HIV-1 binding with the outward-open state of hDAT. Such protein-protein docking and initial screening were also performed for the 11 HIV-1 Tat conformations docking with the 10 MD snapshots of the outward-occluded state of hDAT, and then docking with the 10 MD snapshots of the inward-open state of hDAT. The total number of the selected candidates for HIV-1 Tat binding with all three conformational states of hDAT became 3,000 (i.e. 1,000 + 1,000 + 1,000). These 3,000 candidates were subjected to further MD simulations and binding energy calculations (see Supplemental Data for the computational details) and, finally, the most favorable binding structure was determined with the lowest binding energy.

Construction of plasmids

All point mutations of Tyr88, Lys92, and Tyr470 in hDAT were selected based on the predictions of the 3D-computational modeling and simulations. All mutations in hDAT were generated based on wild-type human DAT (WT-hDAT) sequence (NCBI, cDNA clone MGC: 164608 IMAGE: 40146999) by site-directed mutagenesis. Synthetic cDNA encoding hDAT subcloned into pcDNA3.1+ (provided by Dr. Haley E Melikian, University of Massachusetts) was used as a template to generate mutants using QuikChange™ site-directed mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Tech, Santa Clara CA). The sequence of the mutant construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing at University of South Carolina EnGenCore facility. Plasmids DNA were propagated and purified using plasmid isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA)

Cell culture and DNA transfection

Pheochromocytoma (PC12, ATCC #CRL-1721) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium supplemented with 15 % horse serum, 2.5 % bovine calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin). Both cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For hDAT (wild-type or mutant) transfection, cells were seeded into 24 well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/cm2. After 24 h, cells were transfected with WT or mutant hDAT plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Tech, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were used for the experiments after 24 h of transfection.

[3H]DA uptake assay

Twenty four hours after transfection, [3H]DA uptake in PC12 cells transfected with WT-hDAT and mutants was performed as reported previously.75 To determine whether Tat inhibits DA uptake, kinetic analyses of [3H]DA uptake were conducted in WT-hDAT and its mutants in the absence or presence of Tat. In brief, [3H]DA uptake was measured in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) buffer (final concentration in mM: 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.5 MgSO4, 1.25 CaCl2, 1.5 KH2PO4, 10 D-glucose, 25 HEPES, 0.1 EDTA, 0.1 pargyline, and 0.1 L-ascorbic acid; pH 7.4) containing one of 6 concentrations of unlabeled DA (final DA concentrations, 1.0 nM–5 μM) and a fixed concentration of [3H]DA (500,000 dpm/well, specific activity, 21.2 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA). In parallel, nonspecific uptake of each concentration of [3H]DA (in the presence of 10 μM nomifensine, final concentration) was subtracted from total uptake to calculate DAT-mediated uptake. To determine the inhibitory effects of Tat on [3H]DA uptake, cells transfected with WT hDAT or mutant were preincubated with or without Tat1-86 (500 nM, final concentration) at room temperature for 20 min followed by addition of [3H]DA for an additional 8 min. The reaction was conducted at room temperature for 8 min and terminated by washing twice with ice cold uptake buffer. Cells were lysed in 500 μl of 1% SDS for an hour and radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (model Tri-Carb 2900TR; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA). Kinetic data were analyzed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the NIH (grants R01 DA035714, R01 DA035552, R01 DA032910, and R01 DA025100) and the NSF (grant CHE-1111761). The authors acknowledge the Computer Center at the University of Kentucky for supercomputing time on a Dell Supercomputer Cluster consisting of 388 nodes or 4,816 processors.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Figure S1 for amino acid sequence of B-type HIV-1 Tat (Tat Bru) protein.

References

- 1.Ferris MJ, Frederick-Duus D, Fadel J, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. The human immunodeficiency virus-1–associated protein, Tat1-86, impairs dopamine transporters and interacts with cocaine to reduce nerve terminal function: A no-net-flux microdialysis study. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1292–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valdiserri RO. Commentary: Thirty Years of AIDS in America: A Story of Infinite Hope. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23:479–494. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Who, U., and Unicef . Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvers JM, Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Beckley J, Olton P, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Dopaminergic marker proteins in the substantia nigra of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected brains. Journal of neurovirology. 2006;12:140–145. doi: 10.1080/13550280600724319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace DR, Dodson S, Nath A, Booze RM. Estrogen attenuates gp120-and tat1–72-induced oxidative stress and prevents loss of dopamine transporter function. Synapse. 2006;59:51–60. doi: 10.1002/syn.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst T, Yakupov R, Nakama H, Crocket G, Cole M, Watters M, Ricardo-Dukelow ML, Chang L. Declined neural efficiency in cognitively stable human immunodeficiency virus patients. Annals of neurology. 2009;65:316–325. doi: 10.1002/ana.21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey AN, Sypek EI, Singh HD, Kaufman MJ, McLaughlin JP. Expression of HIV-Tat protein is associated with learning and memory deficits in the mouse. Behavioural brain research. 2012;229:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris MJ, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Neurotoxic profiles of HIV, psychostimulant drugs of abuse, and their concerted effect on the brain: current status of dopamine system vulnerability in NeuroAIDS. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:883–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorder: pathophysiology in relation to drug addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1187:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Ananthan S, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Recombinant human immunodeficiency virus-1 transactivator of transcription1–86 allosterically modulates dopamine transporter activity. Synapse. 2011;65:1251–1254. doi: 10.1002/syn.20949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paris JJ, Carey AN, Shay CF, Gomes SM, He JJ, McLaughlin JP. Effects of conditional central expression of HIV-1 Tat protein to potentiate cocaine-mediated psychostimulation and reward among male mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;39:380–388. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Valle L, Croul S, Morgello S, Amini S, Rappaport J, Khalili K. Detection of HIV-1 Tat and JCV capsid protein, VP1, in AIDS brain with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Journal of neurovirology. 2000;6:221–228. doi: 10.3109/13550280009015824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson L, Liu J, Nath A, Jones M, Raghavan R, Narayan O, Male D, Everall I. Detection of the human immunodeficiency virus regulatory protein tat in CNS tissues. Journal of neurovirology. 2000;6:145–155. doi: 10.3109/13550280009013158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamers SL, Salemi M, Galligan DC, Morris A, Gray R, Fogel G, Zhao L, McGrath MS. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 evolutionary patterns associated with pathogenic processes in the brain. Journal of neurovirology. 2010;16:230–241. doi: 10.3109/13550281003735709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aksenova MV, Silvers JM, Aksenov MY, Nath A, Ray PD, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity in primary cultures of rat midbrain fetal neurons: changes in dopamine transporter binding and immunoreactivity. Neuroscience letters. 2006;395:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J, Reith MEA. Role of dopamine transporter in the action of psychostimulants, nicotine, and other drugs of abuse. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2008;7 doi: 10.2174/187152708786927877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, Mactutus CF, Wallace DR, Booze RM. HIV-1 Tat protein-induced rapid and reversible decrease in [3H]dopamine uptake: dissociation of [3H]dopamine uptake and [3H]2beta-carbomethoxy-3-beta-(4-fluorophenyl)tropane (WIN 35,428) binding in rat striatal synaptosomes. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2009;329:1071–1083. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.150144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferris MJ, Frederick-Duus D, Fadel J, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Hyperdopaminergic tone in HIV-1 protein treated rats and cocaine sensitization. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010;115:885–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purohit V, Rapaka R, Shurtleff D. Drugs of abuse, dopamine, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders/HIV-associated dementia. Molecular neurobiology. 2011;44:102–110. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midde NM, Gomez AM, Zhu J. HIV-1 Tat protein decreases dopamine transporter cell surface expression and vesicular monoamine transporter-2 function in Rat striatal synaptosomes. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2012;7:629–639. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagashev A, Sawaya BE. Roles and functions of HIV-1 Tat protein in the CNS: an overview. Virology journal. 2013;10:358. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Yoon J-H, Kim Y-S. HIV-1 Tat interacts with and regulates the localization and processing of amyloid precursor protein. PloS one. 2013;8:e77972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr., Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, Group C. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaskill PJ, Calderon TM, Luers AJ, Eugenin EA, Javitch JA, Berman JW. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection of human macrophages is increased by dopamine: a bridge between HIV-associated neurologic disorders and drug abuse. The American journal of pathology. 2009;175:1148–1159. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckner CM, Luers AJ, Calderon TM, Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Neuroimmunity and the blood-brain barrier: molecular regulation of leukocyte transmigration and viral entry into the nervous system with a focus on neuroAIDS. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology. 2006;1:160–181. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nath A, Maragos WF, Avison MJ, Schmitt FA, Berger JR. Acceleration of HIV dementia with methamphetamine and cocaine. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:66–71. doi: 10.1080/135502801300069737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meade CS, Conn NA, Skalski LM, Safren SA. Neurocognitive impairment and medication adherence in HIV patients with and without cocaine dependence. J Behav Med. 2011;34:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9293-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meade CS, Lowen SB, MacLean RR, Key MD, Lukas SE. fMRI brain activation during a delay discounting task in HIV-positive adults with and without cocaine dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang L, Wang G-J, Volkow ND, Ernst T, Telang F, Logan J, Fowler JS. Decreased brain dopamine transporters are related to cognitive deficits in HIV patients with or without cocaine abuse. Neuroimage. 2008;42:869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar AM, Ownby RL, Waldrop-Valverde D, Fernandez B, Kumar M. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in the CNS and decreased dopamine availability: relationship with neuropsychological performance. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:26–40. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger JR, Arendt G. HIV dementia: the role of the basal ganglia and dopaminergic systems. Journal of psychopharmacology. 2000;14:214–221. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sardar AM, Czudek C, Reynolds GP. Dopamine deficits in the brain: the neurochemical basis of parkinsonian symptoms in AIDS. Neuroreport. 1996;7:910–912. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199603220-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar AM, Fernandez JB, Singer EJ, Commins D, Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Kumar M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the central nervous system leads to decreased dopamine in different regions of postmortem human brains. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:257–274. doi: 10.1080/13550280902973952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheller C, Arendt G, Nolting T, Antke C, Sopper S, Maschke M, Obermann M, Angerer A, Husstedt IW, Meisner F, Neuen-Jacob E, Muller HW, Carey P, Ter Meulen V, Riederer P, Koutsilieri E. Increased dopaminergic neurotransmission in therapy-naive asymptomatic HIV patients is not associated with adaptive changes at the dopaminergic synapses. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:699–705. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beuming T, Kniazeff J, Bergmann ML, Shi L, Gracia L, Raniszewska K, Newman AH, Javitch JA, Weinstein H, Gether U, Loland CJ. The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:780–789. doi: 10.1038/nn.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koutsilieri E, Czub S, Scheller C, Sopper S, Tatschner T, Stahl-Hennig C, ter Meulen V, Riederer P. Brain choline acetyltransferase reduction in SIV infection. An index of early dementia? Neuroreport. 2000;11:2391–2393. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koutsilieri E, ter Meulen V, Riederer P. Neurotransmission in HIV associated dementia: a short review. J Neural Transm. 2001;108:767–775. doi: 10.1007/s007020170051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst T, Jiang CS, Nakama H, Buchthal S, Chang L. Lower brain glutamate is associated with cognitive deficits in HIV patients: a new mechanism for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2010;32:1045–1053. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrarese C, Aliprandi A, Tremolizzo L, Stanzani L, De Micheli A, Dolara A, Frattola L. Increased glutamate in CSF and plasma of patients with HIV dementia. Neurology. 2001;57:671–675. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aksenov MY, Aksenova M, Mactutus C, Booze RM. D1/NMDA receptors and concurrent methamphetamine+ HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2012;7:599–608. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9362-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.S Silverstein P, Shah A, Weemhoff J, Kumar S, P Singh D, Kumar A. HIV-1 gp120 and drugs of abuse: interactions in the central nervous system. Current HIV research. 2012;10:369–383. doi: 10.2174/157016212802138724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamza A, Cho H, Tai H-H, Zhan C-G. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Cocaine Binding with Human Butyrylcholinesterase and Its Mutants. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109:4776–4782. doi: 10.1021/jp0447136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W, Cho H, Yang G, Tai H-H, Zhan C-G. Computational redesign of human butyrylcholinesterase for anticocaine medication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:16656–16661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507332102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao D, Cho H, Yang W, Pan Y, Yang G, Tai H-H, Zhan C-G. Computational Design of a Human Butyrylcholinesterase Mutant for Accelerating Cocaine Hydrolysis Based on the Transition-State Simulation13. Angewandte Chemie. 2006;118:669–673. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W, Cho H, Zhan C-G. Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Simulation on the Transition States of Cocaine Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Human Butyrylcholinesterase and Its Mutants. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:13537–13543. doi: 10.1021/ja073724k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng F, Yang W, Ko M-C, Liu J, Cho H, Gao D, Tong M, Tai H-H, Woods JH, Zhan C-G. Most Efficient Cocaine Hydrolase Designed by Virtual Screening of Transition States. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:12148–12155. doi: 10.1021/ja803646t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhan C-G, Zheng F, Landry DW. Fundamental reaction mechanism for cocaine hydrolysis in human butyrylcholinesterase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2462–2474. doi: 10.1021/ja020850+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng F, Xue L, Hou S, Liu J, Zhan M, Yang W, Zhan C-G. A highly efficient cocaine detoxifying enzyme obtained by computational design. Nature Commun. 2014;5:3457. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4457. doi: 3410.1388/ncomms4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Brimijoin S. Lasting reduction of cocaine action in neostriatum--a hydrolase gene therapy approach. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;330:449–457. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fang L, Chow KM, Hou S, Xue L, Rodgers DW, Zheng F, Zhan C-G. Rational design, preparation, and characterization of a therapeutic enzyme mutant with improved stability and function for cocaine detoxification. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:1764–1772. doi: 10.1021/cb500257s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volkow N, Wang G-J, Fischman M, Foltin R, Fowler J, Abumrad N, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley S, Pappas N. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. 1997 doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitayama S, Shimada S, Xu H, Markham L, Donovan DM, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter site-directed mutations differentially alter substrate transport and cocaine binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:7782–7785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harrod S, Mactutus C, Fitting S, Hasselrot U, Booze R. Intra-accumbal Tat1–72 alters acute and sensitized responses to cocaine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;90:723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang G-J, Chang L, Volkow ND, Telang F, Logan J, Ernst T, Fowler JS. Decreased brain dopaminergic transporters in HIV-associated dementia patients. Brain. 2004;127:2452–2458. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsieh PC, Yeh TL, Lee IH, Huang HC, Chen PS, Yang YK, Chiu NT, Lu RB, Liao M-H. Correlation between errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and the availability of striatal dopamine transporters in healthy volunteers. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN. 2010;35:90. doi: 10.1503/jpn.090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mozley LH, Gur RC, Mozley PD, Gur RE. Striatal dopamine transporters and cognitive functioning in healthy men and women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1492–1499. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, Wu K, Bosch RJ, Wu J, McArthur JC, Collier AC, Evans SR, Ellis RJ. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. Aids. 2007;21:1915–1921. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, Chen T, Johnson KM, Jennings K, Freeman DH, Jr, Soukup VM. Prefrontal dopaminergic and enkephalinergic synaptic accommodation in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and encephalitis. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2012;7:686–700. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giros B, el Mestikawy S, Godinot N, Zheng K, Han H, Yang-Feng T, Caron MG. Cloning, pharmacological characterization, and chromosome assignment of the human dopamine transporter. Molecular Pharmacology. 1992;42:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beuming T, Shi L, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Molecular pharmacology. 2006;70:1630–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rudnick G. Cytoplasmic Permeation Pathway of Neurotransmitter Transporters. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7462–7475. doi: 10.1021/bi200926b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl–dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Forrest LR, Tavoulari S, Zhang Y-W, Rudnick G, Honig B. Identification of a chloride ion binding site in Na+/Cl–dependent transporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:12761–12766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zomot E, Bendahan A, Quick M, Zhao Y, Javitch JA, Kanner BI. Mechanism of chloride interaction with neurotransmitter: sodium symporters. Nature. 2007;449:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nature06133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh SK, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. Antidepressant binding site in a bacterial homologue of neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2007;448:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature06038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh SK, Piscitelli CL, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. A competitive inhibitor traps LeuT in an open-to-out conformation. Science. 2008;322:1655–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1166777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piscitelli CL, Krishnamurthy H, Gouaux E. Neurotransmitter/sodium symporter orthologue LeuT has a single high-affinity substrate site. Nature. 2010;468:1129–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature09581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang H, Elferich J, Gouaux E. Structures of LeuT in bicelles define conformation and substrate binding in a membrane-like context. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19:212–219. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krishnamurthy H, Gouaux E. X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature. 2012;481:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E. X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism. Nature. 2013;503:85–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang X, Zhan C-G. How dopamine transporter interacts with dopamine: insights from molecular modeling and simulation. Biophysical journal. 2007;93:3627–3639. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kniazeff J, Shi L, Loland CJ, Javitch JA, Weinstein H, Gether U. An intracellular interaction network regulates conformational transitions in the dopamine transporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:17691–17701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800475200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang X, Gu HH, Zhan C-G. Mechanism for cocaine blocking the transport of dopamine: insights from molecular modeling and dynamics simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:15057–15066. doi: 10.1021/jp900963n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koldsø H, Christiansen AB, Sinning S, Schiøtt B. Comparative modeling of the human monoamine transporters: similarities in substrate binding. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2012;4:295–309. doi: 10.1021/cn300148r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Midde NM, Huang X, Gomez AM, Booze RM, Zhan CG, Zhu J. Mutation of tyrosine 470 of human dopamine transporter is critical for HIV-1 Tat-induced inhibition of dopamine transport and transporter conformational transitions. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology. 2013;8:975–987. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Šali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nayeem A, Sitkoff D, Krystek S. A comparative study of available software for high-accuracy homology modeling: From sequence alignments to structural models. Protein Science. 2006;15:808–824. doi: 10.1110/ps.051892906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pierce BG, Hourai Y, Weng Z. Accelerating protein docking in ZDOCK using an advanced 3D convolution library. PloS one. 2011;6:e24657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham Iii TE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Swails J, Goetz AW, Kolossváry I, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Wolf RM, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh MJ, Cui G, Roe DR, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Salomon-Ferrer R, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman PA. AMBER 12. University of California; San Francisco: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Péloponèse JM, Grégoire C, Opi S, Esquieu D, Sturgis J, Lebrun E, Meurs E, Collette Y, Olive D, Aubertin AM, Witvrow M, Pannecouque C, De Clercq E, Bailly C, Lebreton J, Loret EP. 1H-13C nuclear magnetic resonance assignment and structural characterization of HIV-1 Tat protein. C. R. Acad. Sci. III, Sci. Vie. 2000;323:883–894. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)01228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller BR, III, McGee TD, Jr, Swails JM, Homeyer N, Gohlke H, Roitberg AE. MMPBSA. py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8:3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Midde NM, Yuan Y, Quizon PM, Sun WL, Huang X, Zhan C-G, Zhu J. Mutations at Tyrosine 88, Lysine 92 and Tyrosine 470 of Human Dopamine Transporter Result in an Attenuation of HIV-1 Tat-Induced Inhibition of Dopamine Transport. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015;10:122–135. doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9583-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Studio D. version 2.5. Accelrys Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson–Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:W665–W667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pierce B, Weng Z. ZRANK: reranking protein docking predictions with an optimized energy function. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2007;67:1078–1086. doi: 10.1002/prot.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.