Introduction

Perinatal psychiatric illness is common and can carry significant morbidity and mortality for mother, fetus, child, and family.1,2 Among women pregnant in the past year, up to 25.3% meet criteria for a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition psychiatric disorder, 8% meet criteria for a new psychiatric disorder, and 0.4% meet criteria for a psychotic disorder.3 Maternal schizophrenia and acute psychosis during pregnancy have been associated with higher risks of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, parenting difficulties,4 and loss of custodial or parental rights.2 Perinatal psychiatric illness may impair a woman's judgment, self-care, decision-making, giving rise to sensitive and complex legal and ethical issues related to psychiatric, obstetric, and neonatal care.5,6 Although the literature on perinatal psychiatric illness is growing rapidly, there is a relative absence of information on the complex legal and ethical issues that may arise in the care of these patients, especially regarding the question of pregnancy termination.

Case Report

Ms. A, a 32-year-old African American woman with a psychiatric history of schizoaffective disorder, resided at a state psychiatric hospital and was under legal guardianship. She became aware of her pregnancy at 9 weeks of gestational age, after she missed her menstrual cycle and a urine pregnancy test confirmed her pregnancy. She had a prenatal care visit at 9.5 weeks of gestational age and was immediately referred for a consultation with the perinatal psychiatrist whose clinic was collocated in her obstetric (OB) clinic.

Ms. A had been in residential psychiatric care since the age of 16 years. Her aunt was her appointed legal guardian. She had a long history of self-injurious behaviors, including an attempt to strangle herself several months before presenting to the OB clinic for prenatal care. Ms. A presented at 12 weeks stating that the pregnancy was unplanned and that the father of the baby was a friend she visited while out on a pass from the hospital. She reported that she was declining her psychiatric medications, because she believed the hospital staff was attempting to kill her baby.

Ms. A's acute paranoia and self-injurious behaviors led to concerns about her decisional capacity, and the role of her legal guardian was explored. At 16 weeks of gestational age, a multidisciplinary meeting was held with her guardian, the OB team, the residential treatment team, and the consulting perinatal psychiatrist to develop a pregnancy and delivery plan. At the meeting, the treatment team at the state hospital shared that Ms. A had been vacillating in her desire to continue with the pregnancy and had discussed the possibility of termination. Owing to hospital policy, a termination would need to be completed by 18 weeks of gestation.

The guardian wished to honor Ms. A's choice about the pregnancy if Ms. A was capable of making an informed decision. In the alternative, the guardian wished to rely on Ms. A's stated or implied values and preferences regarding the pregnancy if Ms. A could communicate them.

Ms. A met with her therapist and residential psychiatric team regarding her options: termination before 18 weeks or carrying the fetus to term with or without the option of adoption. Owing to her expressed preference to terminate the pregnancy, she met with the OB team to further discuss her options. The OB team provided information about dilation and curettage procedure to both Ms. A and her guardian, including risks and benefits, and the alternative option of carrying the fetus to term with or without adoption.

Following this meeting, Ms. A met with her residential treatment team where she continued to express her desire to terminate her pregnancy over a 5-day period. On the sixth day following the OB appointment, the consulting perinatal psychiatrist conducted a capacity assessment with Ms. A’s therapist present. During this meeting, Ms. A became extremely anxious and was unable to verbally express her preferences. She asked to speak to her therapist alone and together they decided she would be more comfortable communicating in writing. She was able to demonstrate a factual understanding of the dilation and curettage procedure and an appreciation of the risks and alternatives of pregnancy termination by citing the “pros and cons” of keeping her pregnancy vs terminating. Ms. A showed a coherent and logical reasoning process for electing termination. Specifically, she explained that she felt she would not be a fit mother; that her role as a parent would detract from her well-being, which would ultimately negatively affect her child. Foster care and adoption were not acceptable alternatives. The following is an excerpt of what she wrote regarding her decision:

This decision of abortion was completely my decision. I was not pressured into making this decision. …I do not want to go through adoption or foster care because that is not always a good option. Also, I would be worse off having the baby and not able to be with it [sic]. Either way, I would be emotionally scarred, but it would be easier to move on in my life if I take this route. I understand this means an irreversible termination of pregnancy. The fetus tissue will be taken out of my body. This was not a decision based on hearing voices, I do not hear voices. I thought about the pros and cons…

Based on the capacity evaluation, the psychiatric consultant opined that Ms. A's decision met the requirements of a capacitated decision, even though she lacked legal authority to make this decision on her own behalf under the terms of her guardianship. Guided by Ms. A's expressed preference and the psychiatric opinion regarding her ability to understand and rationally consider the decision, Ms. A's guardian consented to termination of the pregnancy. Ms. A subsequently underwent dilation and curettage to terminate her pregnancy. There were no complications.

Case Discussion

A diagnosis of a psychotic-spectrum illness does not in and of itself prohibit an individual from making informed decisions about their medical treatment, even pregnancy termination. Ms. A had dual vulnerabilities: pregnancy and chronic mental illness. Providers must balance autonomy and beneficence-based obligations to the pregnant woman by both respecting capacitated reproductive preferences/decisions and protecting the woman from harm. The lack of ethical consensus on this matter and the emergence of increasingly restrictive abortion legislation in some US jurisdictions add complexity to cases such as Ms. A's case.

Pregnancy Planning

When compared with women without a major mental illness, women with schizophrenia report a lack of knowledge about and restricted access to contraception and that they are less likely to use birth control because of unplanned intercourse. They also may have diminished capacity to consent for intercourse.7 Increasing access to different modes of contraception and discussing family planning with patients and their guardians may help mitigate the risk of unplanned and unwanted pregnancies. Providing sexual education and rape prevention training may also facilitate informed choices and decisions regarding intercourse. Safeguards, such as consistent testing for sexually-transmitted diseases, frequent pregnancy tests, and substance use education, should also be established to protect women who may not be able to consent to intercourse.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the process by which a patient (or her surrogate) gives permission to the physician to do something to her or on her behalf. It requires that the permission given by the patient is both knowing and voluntary. The physician's obligation is to present the patient with sufficient information for the patient to make the decision. How much information the physician must disclose varies among jurisdictions. A small majority of US states follow the rule that the information presented must meet the standard of what the reasonable or average physician would disclose. The other 2 standards are patient centered, i.e., they set the amount of information that must be presented as what either the reasonable or the average patient would want to know, or, alternatively in a minority of jurisdictions, what the particular patient would want to know under the given circumstances.

Capacity Assessment

Capacity is the threshold requirement for decision-making, and no informed consent can occur without a capacitated decision-maker. Without informed consent, the physician lacks legal authority to do anything for or to the patient. Informed consent is the bedrock upon which all medical care is undertaken.8 The determination of capacity begins with the physician having a detailed discussion with the patient regarding pregnancy and options. The prevailing standard for the determination of decisional capacity regarding medical care relies on the presence of 4 key components: (1) ability to communicate a choice, (2) ability to understand relevant information (factual understanding), (3) ability to appreciate the nature of the situation and its likely consequences (appreciation), and (4) ability to manipulate information rationally.8

The determination of capacity does not begin and end with a single conversation. Detailed, yet easily understandable, information communicated during the informed consent process can establish a therapeutic alliance and help the patient understand the unique aspects of her condition. To demonstrate capacity, the patient must exhibit the ability to consider her current situation and consequences if she takes the pregnancy to term.

Enhancing Decision-Making Capacity

It is imperative to enhance the patients' ability to advocate for themselves and participate in the informed consent process. A multidisciplinary team approach should emphasize collaboration and include an assessment of how one's own beliefs may be influencing or interfering with the decision-making.9 When a pregnant woman lacks decisional capacity related to pregnancy, the first determination should be whether the lack of capacity is reversible and if so, the condition should be treated with medication, psychotherapy, and other appropriate treatments to restore capacity. In geriatric populations with psychotic illnesses, the understanding of consent procedures can be enhanced through repetition and PowerPoint presentations for clarification and education.10 Although not studied in women of childbearing age, such approaches could be used to enhance informed consent discussions and patients' understanding of the various factors involved in continuing pregnancy to term vs undergoing termination of pregnancy.

A thorough clinical assessment, including formulation of key issues, effect of termination on the patient and the distress related to it, and continued pregnancy, is critical to understanding the patient's framework of beliefs to guide decision making and to developing an ethically and legally sound plan for decision-making. In this case, Ms. A did not see the value of taking psychiatric medications as she felt that this was the staff's attempt to kill her baby. This appeared to reflect some degree of paranoia and also tended to support a desire to continue the pregnancy. Over time, however, she demonstrated an evolving understanding and appreciation of her situation and expressed consistent preference to terminate the pregnancy. Capacity assessments should take into account whether and how women's underlying illness affects their capability to participate in an informed consent and allow for the natural process of evolution of decision-making in terms of adjustment to and acceptance of pregnancy. If incapacity is not reversible, a substitute decision-maker must be sought either through an advance directive, guardianship proceeding, or in a limited number of states, a statutory mechanism.

Autonomy and Substituted Judgment

When patients are under legal guardianship, it is critical to understand the scope of the guardianship to determine who the legally recognized decision-maker is. However, as this case illustrates, even if a surrogate such as a guardian is the legally recognized decision-maker, the patient may nonetheless be included in the process to promote the patient's autonomy and also determine substituted judgment with greater fidelity. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the prevailing laws and regulations regarding limitations of the rights of surrogate decision makers to make decisions related to pregnancy termination, as general powers of guardianship or advanced directives may not apply to pregnancy termination and court or other administrative interventions may be required.

There are several degrees to which the autonomy of an individual under guardianship may be recognized. In certain circumstances, a patient lacking decisional capacity or ability to appreciate the reality of her circumstances or both cannot be involved in the decisional process. For example, a patient who is unable to make decisions in a reality-based fashion (e.g., denies the pregnancy) or is unable to assure her own safety. In such cases, deferring decision-making to the guardian may be the best approach. But in cases of less dense decisional incapacity, the patient under guardianship may be included in the decision-making process. In cases where guardianship either does not authorize or explicitly precludes the guardian from making decisions, assisted decision-making is essential.11 In such cases, resources are used to bolster the ability of the patient to make or at least robustly contribute to decisions. For example, a patient may be invited to consider her previous values regarding pregnancy and motherhood. Assisted decision-making helps prevent unjustifiably taking over a patient's decision-making regarding her pregnancy to avoid possible adverse outcomes.11

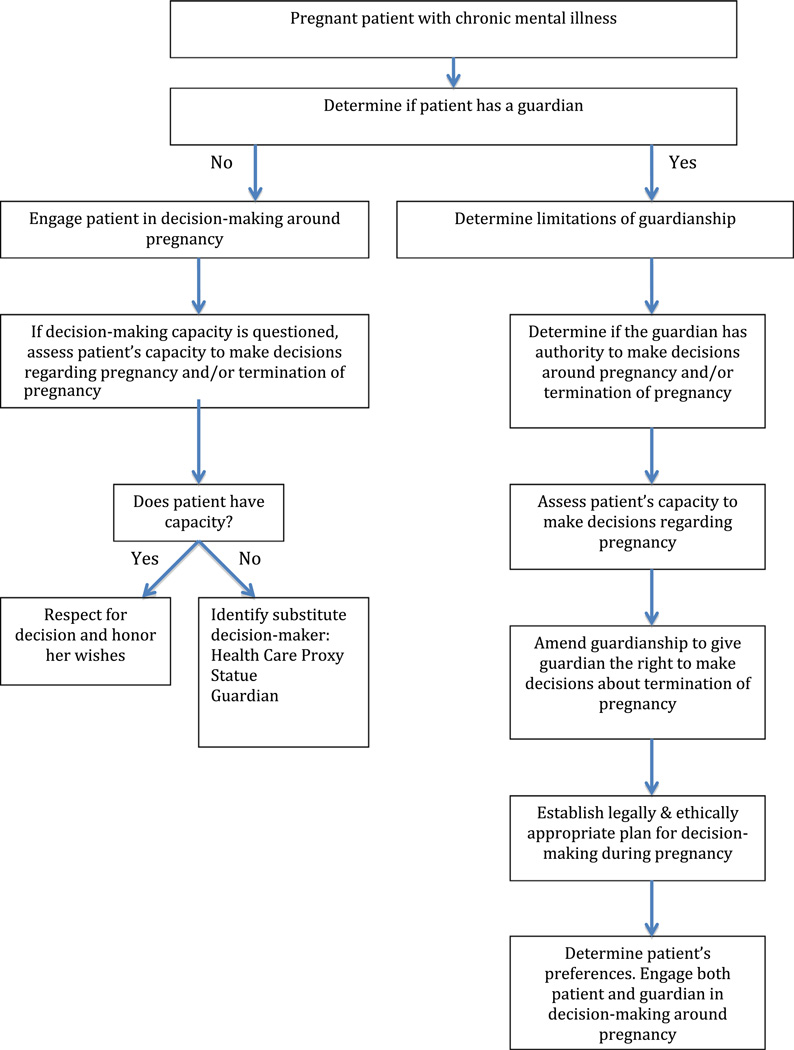

Substituted judgment or surrogate decision-making requires that decisions be made for the patient based on information about the patient's long-standing values or preferences, so long as those can be reliably identified.12 All available management strategies should be explained to the surrogate, and the team should work together with the patient and the surrogate to identify patients' relevant values and beliefs. If patient's values are unknown, best interests' standard should guide surrogate decision-making.12 The Figure offers a guide to navigating decision-making capacity of pregnant women with chronic mental illness.

FIGURE.

Guide to Navigating Decision-Making Capacity of Pregnant Women With Chronic Mental Illness.

Considerations During Pregnancy

Although guardianship of an adult focuses on the wishes or best interest of the individual, pregnancy introduces the added complexity that the fetus may have legal or ethical status or both. Although the fetus generally does not have rights or legal status as a person, per se, the law generally recognizes that the rights of the mother regarding the fetus are not absolute. For example, restrictions on elective pregnancy termination follow this principle: although pregnant women may have broad rights early in pregnancy, as fetus develops, the autonomy of the pregnant woman vis-à-vis the fetus is limited. These limitations apply to patients under guardianship as well. The balance between the status of the fetus and the pregnant woman varies depending on the circumstances. Specifically, the well-being of the mother is generally not subordinated to the well-being of the fetus, if it is life threatening or have other substantial health risk to the pregnant woman. It is thus important to consider maternal health as a central outcome during decision-making.

The viable fetus is considered a “fetal patient” deserving of certain protections, but the previable fetus is conferred the status fetal patient only when the pregnant woman confers such status on it.4 The future of the pregnancy and the fetus depends upon a capacitated decision regarding the fetus. If the patient lacks the capacity to make an informed decision regarding her pregnancy and does not have a guardian, measures must be taken to achieve a capacitated decision-maker both to protect the autonomy of the pregnant woman and to ascertain the relative moral and legal claims of the fetus.

Conclusion

The case of Ms. A, the first published of its kind, exemplifies the complexities, which may arise while providing care to a vulnerable pregnant patient. In this case, a thorough multidisciplinary team approach allowed the team to work with her and her guardian toward a decision regarding termination or continuation of pregnancy, while respecting the patient's ambivalence. The careful, patient, supportive, and individualized care that she received undoubtedly contributed to an outcome, which by all accounts, appears to have been in accordance with the patient's wishes and in her best interest. It is imperative to bring multiple disciplines together, exercise ethical principles, and mind legal issues to arrive at a patient-centered decision.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Byatt received funding support for this work from the National Center for Research Resources, USA and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, USA through Grant number KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Zalpuri, Gramann, Dresner, and Brendel report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:219–229. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson E, Lichtenstein P, Cnattingius S, Murray RM, Hultman CM. Women with schizophrenia: pregnancy outcome and infant death among their offspring. Schizophr Res. 2002;58(2–3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00370-x. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. The fetus as a patient: an essential ethical concept for maternal-fetal medicine. J Matern Fetal Med. 1996;5(3):115–119. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199605/06)5:3<115::AID-MFM3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudzinski DM. Compounding vulnerability: pregnancy and schizophrenia. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(2):W1–W14. doi: 10.1080/15265160500506191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coverdale JH, Bayer TL, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. Respecting the autonomy of chronic mentally ill women in decisions about contraception. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(7):671–674. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller LJ, Finnerty M. Family planning knowledge, attitudes and practices in women with schizophrenic spectrum disorders. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19(4):210–217. doi: 10.3109/01674829809025699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients' competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834–1840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris K, Savell K, Ryan CJ. Psychiatrists and termination of pregnancy: clinical, legal and ethical aspects. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(1):18–27. doi: 10.1177/0004867411432075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeste DV, Dunn LB, Palmer BW, et al. A collaborative model for research on decisional capacity and informed consent in older patients with schizophrenia: bioethics unit of a geriatric psychiatry intervention research center. Psychopharmacology. 2003;171(1):68–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coverdale JH, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. Assisted and surrogate decision making for pregnant patients who have schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):659–664. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007113. [Case Reports] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock D, Buchanan A. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]